Abstract

Background:

One of the aims of the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) is to aid communication between the physician and patient about the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on the patient's life.

Aims:

To investigate the impact of the CAT on the quality of primary care consultations in COPD patients.

Methods:

Primary care physicians across Europe conducted six consultations with standardised COPD patients (played by trained actors). Physicians were randomised to see the patient with the completed CAT (CAT+ arm) or without (no CAT arm) during the consultation. These were videoed and independent assessors scored the physicians on their ability to identify and address patient-specific issues such as depression (sub-score A); review standard COPD issues such as breathlessness (sub-score B); their understanding of the case (understanding score); and their overall performance. The primary endpoint was the global score (sub-scores A+B; scale range 0–40).

Results:

A total of 165 physicians enrolled in the study and carried out six consultations each; 882 consultations were deemed suitable for analysis. No difference was seen between the arms in the global score (no CAT arm 20.3; CAT+ arm 20.7; 95% CI −1.0 to 1.8; p=0.606) or on sub-score A (p=0.255). A statistically significant difference, though of limited clinical relevance, was observed in mean sub-score B (no CAT arm 8.8; CAT+ arm 9.6; 95% CI 0.0 to 1.6; p=0.045). There was no difference in understanding score (p=0.824) or overall performance (p=0.655).

Conclusions:

The CAT is a disease-specific instrument that aids physician assessment of COPD. It does not appear to improve detection of non-COPD symptoms and co-morbidities.

Keywords: COPD, COPD Assessment Test, primary care, randomised controlled trial, standardised patient cases

Introduction

The quality of a consultation provided by a physician can have a profound impact on the quality of care and patient engagement in treatment decisions.1 The most effective consultations are those in which doctors directly acknowledge and respond to patients' problems and concerns.2 Patients often do not present all of their issues in a consultation, which can lead to poor consultation outcome.3 Thus, tools to improve the communication between patient and physician have the potential to enable patient issues to be raised and addressed.

The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) is a patient-completed questionnaire designed to provide a simple and reliable measure of health status in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).4 The CAT is formed of eight questions covering the most burdensome symptoms of COPD such as breathlessness and limitations in daily activities. It has been shown to have similar properties to the more complex health status questionnaires, the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire5 and the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire.6 However, it is shorter, making it suitable for routine clinical use. It has been shown to be sensitive to both exacerbations and improvements in a general COPD population following pulmonary rehabilitation.7

When the CAT was developed, one of its aims was to aid the communication between physician and patient on the impact of COPD. To date, this aspect of the CAT has not been tested. We therefore set out to assess the impact of the CAT on physician-patient communication. In order to test the CAT robustly, we designed a novel study which allowed us to standardise the patients, assessment criteria, and conduct the study across multiple countries.8

Methods

This was a single-visit randomised (1:1) open parallel-group study comparing the quality of physician consultation with or without CAT in a simulated standardised setting. Primary care physicians were screened by telephone interview across five European countries. Those reporting experience of managing COPD patients (at least three), but not of using the CAT, were invited to participate in a physician-patient communication study. The screening questions also covered other diseases and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), so physicians were unaware that the study involved the CAT until they attended their allocated session. Two or four geographically-spread locations were used in each country, depending on the number of physicians required. Physicians attended the sessions in groups of five or six, with two groups per location. Each group was randomised to see the patient with (CAT+ arm) or without (no CAT arm) the completed CAT. A two-level hierarchical design was used, with a randomisation block size of two, without stratification, such that one group was allocated to each arm at each location. The recruiters were blinded to the randomisation.

The UK's National Research Ethics Service confirmed ethical approval was not required. Physicians consented to their participation in the study and were asked about their demography, smoking history, and medical practice experience.

Physicians received brief training on COPD. Those in the CAT+ arm also received brief training on the CAT (about 15 mins of background information, how to interpret overall scores, and how to identify specific areas of concern for the patient). No specific guidelines were provided on actions to take based on the CAT score.

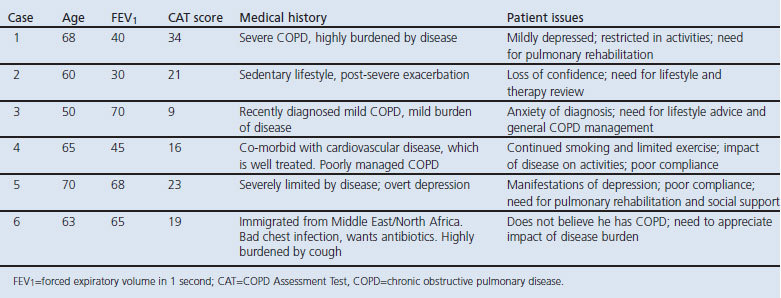

Physicians then undertook consultations with six standardised COPD patients (played by trained actors). Twenty actors fluent in the relevant language performed the role of the COPD patients. They were trained in clinical aspects of COPD, the details of their case, and the way in which to portray a COPD patient accurately. Six COPD cases were designed to cover a variety of disease severities and scenarios relevant to clinical practice and included four or five specific ‘patient issues’ (Table 1). The actors were trained not to proactively raise these issues with the physician, who needed to uncover them by direct enquiry.

Table 1. Summary of standardised cases.

Each physician undertook six consultations. The consultations were videoed and evaluated by independent assessors with experience of assessing physician performance. The assessors were trained to score the physicians on whether they identified and addressed relevant patient issues and reviewed 10 standard COPD issues (0=none, 1=some, 2=high). Scores were captured on an online score sheet and the patient issues scores (sub-score A, out of 20) and COPD review scores (sub-score B, out of 20) were calculated. In addition, physicians were scored on their understanding of the case (‘understanding score‘: poor, acceptable, accurate) and their overall performance (very poor, poor, good, very good).

A maximum of 10 mins was allowed for each case and time taken for the consultation was collected.

The actors provided feedback following each consultation on whether they felt the physician had identified and addressed their issues, the length of the consultation was sufficient, and the consultation was satisfactory.

A pilot study was conducted in the UK to confirm the feasibility of the methodology and to inform the sample size of the study. The pilot study was conducted as described above with 10 physicians and seven assessors. The pilot study results indicated that differences between the arms could be detected with this methodology.8

A benchmarking exercise was undertaken by all assessors of the main study to assess the variability and reliability of the scores. Assessors reviewed two high-scoring and two low-scoring consultations from the pilot study, with and without CAT. While significant variability in the actual score and a difference in mean total scores across the countries were identified, the ranking and delta between the high and low scoring consultations were generally consistent.8

The primary endpoint for the study was mean global score (combined sub-scores A and B) which had a scale of 0 (worst) to 40 (best). Since this measure had not been previously trialled, the sensitivity or potential magnitude of difference between the arms was unknown. The investigators agreed that a difference of 10% (i.e. 4 points) between the arms would be convincing as a true difference between the arms. The sample size was calculated based on conservative results of the pilot study. In order to achieve 90% power to identify a difference of at least 3 points with a standard deviation of 12 points, 752 consultations were needed, allowing for 10% missing data but no confounders.

Sub-scores A and B were also designated as secondary outcomes; all scores were analysed using repeated measures analysis of variance with a linear mixed model. Differences in global score and sub-scores A and B were tested with a chi-square test or a Fisher's exact test. ‘Understanding score’ and overall assessment grading were analysed with a generalised estimating equations model. To account for the assessor effect, as identified in the benchmarking exercise, both assessor and case were included as adjustment variables in the models. The order in which physicians saw the cases was also included to account for any training effect. A secondary analysis where physician demographics were included as covariates was conducted. The statistical analysis was conducted using SAS V.9.1.

Results

Participants

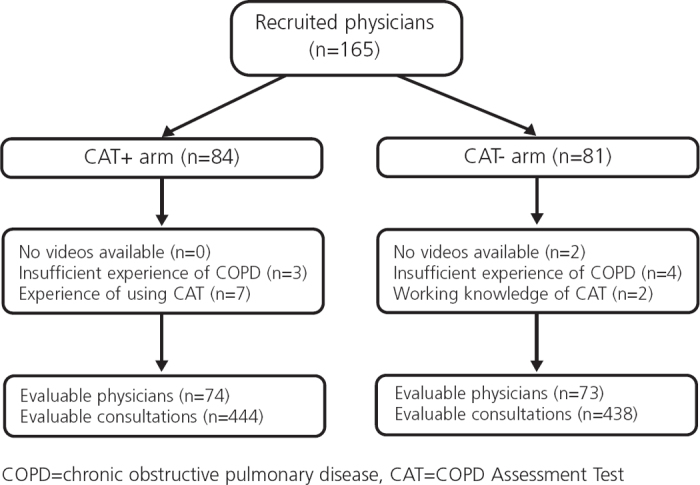

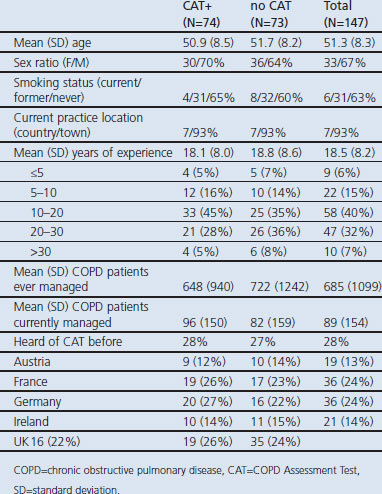

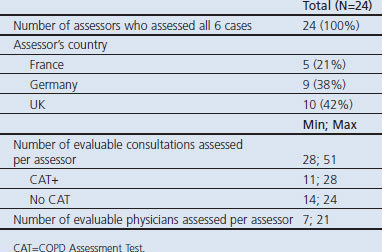

A total of 165 physicians were recruited between October 2010 and February 2011. Due to technical issues, the videos from two physicians could not be assessed. A further 16 physicians did not meet the inclusion criteria (reported either experience of using the CAT or insufficient experience of managing COPD patients at the time of the filming), giving 147 evaluable physicians in the study (Figure 1). The evaluable physicians represent a broad range of experiences, with no major differences between the arms (Table 2). All evaluable physicians had six consultations assessed, providing 882 assessed videos. Twenty-four assessors across three countries assessed between 28 and 51 videos each, including at least one occurrence of each standardised case, with an even split of no CAT and CAT+ videos (Table 3).

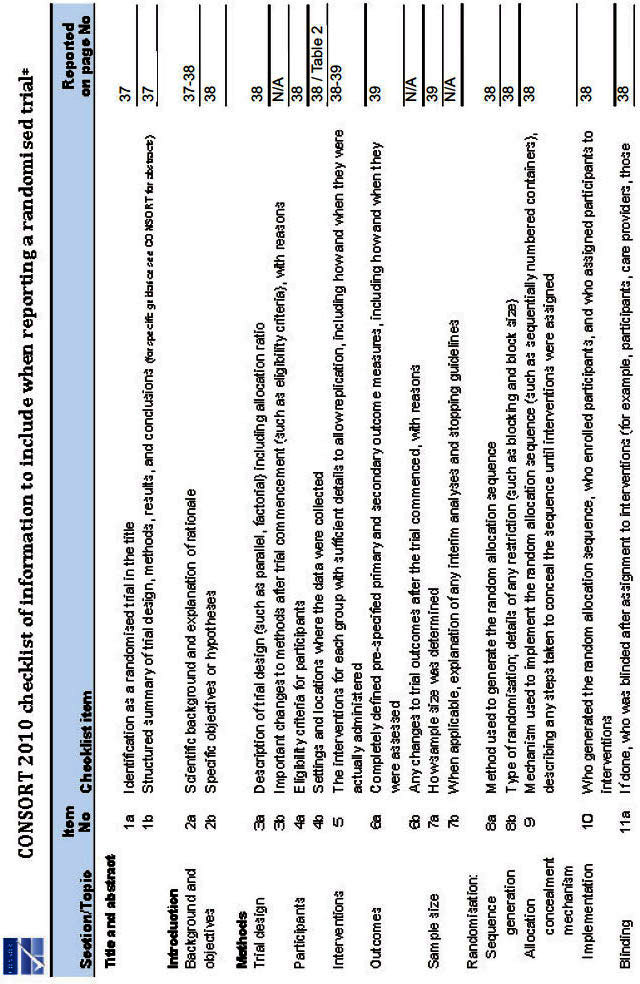

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of physicians recruited into the study

Table 2. Characteristics of evaluable physicians.

Table 3. Assessors' profile and workload.

Efficacy analysis

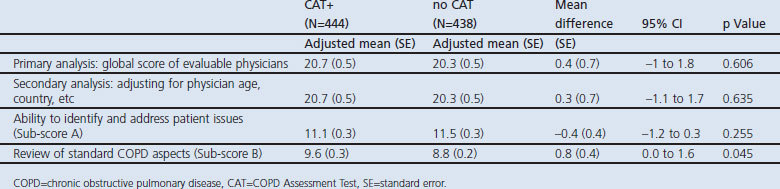

The adjusted mean global score of evaluable physicians in the no CAT arm was 20.3 compared with 20.7 in the CAT+ arm (Table 4).

Table 4. Adjusted mean analysis of global score, sensitivity analyses, sub-score A and sub-score B.

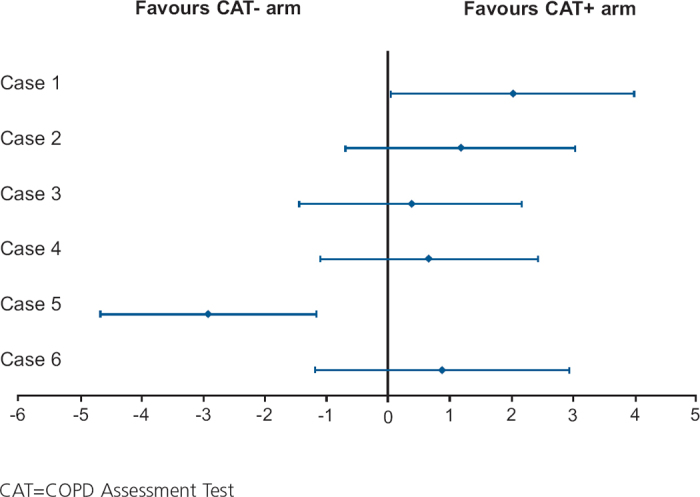

The difference between the arms was not statistically significant (difference 0.4, 95% CI −1.0 to 1.8, p=0.606). A sensitivity analysis using all available consultations also showed no difference between the arms (p=0.548). Similarly, there was no difference between the arms after controlling for factors such as country and age (p=0.635). When the global score was assessed by case, clear differences could be seen between the cases (Figure 2). The CAT significantly improved the global score for the patient heavily burdened with COPD (case 1), while it significantly reduced the global score for the case with major depression (case 5).

Figure 2.

Mean difference and 95% confidence intervals of global score in CAT+ and no CAT arms by case

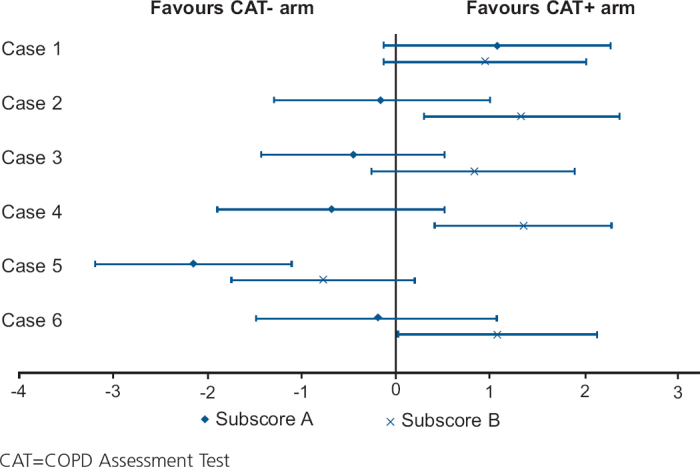

The impact of CAT varied between sub-scores A and B and across cases (Table 4 and Figure 3). The adjusted mean of sub-score A in the no CAT and CAT+ arms was 11.5 and 11.1 respectively (p=0.255), and only case 5 showed a significant difference between the arms (in favour of the no CAT arm). When individual items of sub-score A were investigated, ‘poor appetite and diet’ in case 5 was significantly identified and addressed more in the no CAT arm than in the CAT+ arm (p<0.002, data not shown).

Figure 3.

Mean difference and 95% confidence intervals of sub-scores A (patient-specific issues) and B (standard COPD issues) in CAT+ and no CAT arms by case

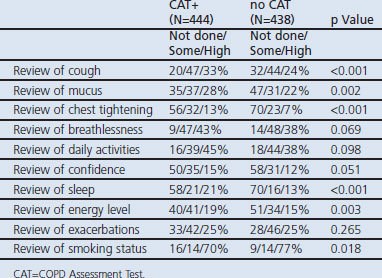

The adjusted mean for sub-score B in the no CAT and CAT+ arms was 8.8 and 9.6 respectively (p=0.045). By case, sub-score B adjusted means were seen to be significantly different between the arms for cases 2, 4 and 6 (all in favour of the CAT+ arm). Physicians in the CAT+ arm consistently achieved more ‘high’ quality reviews of the items that made up the sub-score B (except review of smoking status and exacerbations) than physicians in the no CAT arm (Table 5).

Table 5. Analysis of sub-score B by item.

To test whether the atypical results of case 5 (patient with major depression) were biasing the overall results, a post-hoc analysis removing the data for this case was conducted. The mean global score increased to 20.4 in the no CAT arm and 21.3 in the CAT+ arm (difference 0.93, 95% CI −0.5 to 2.4, p=0.207). The difference between arms was reduced in sub-score A to −0.1 (p=0.748) and increased in sub-score B to 1.1 (p=0.010).

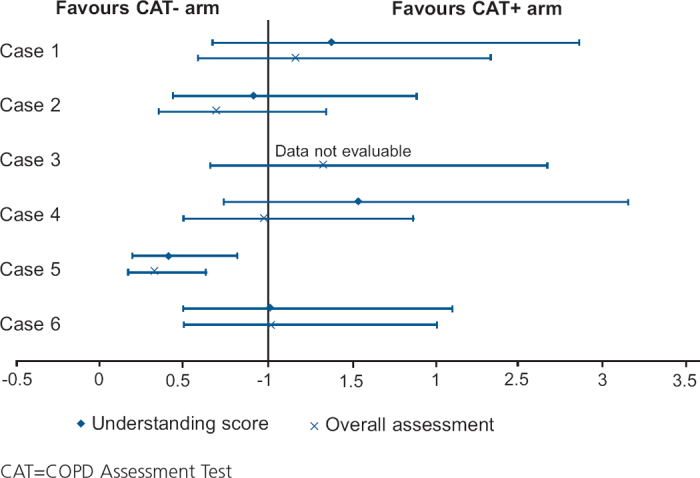

Except for case 5, the CAT had little impact on the physicians' ‘understanding score’ or their overall assessment score (Figure 4). Overall, similar proportions of physicians were given an ‘understanding score’ of poor (19% in both arms), acceptable (39% in the no CAT arm, 42% in the CAT+ arm) or accurate (42% in the no CAT arm, 40% in the CAT+ arm) (OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.7 to 1.4; p=0.824). Likewise, the proportions of physicians scoring an overall assessment score of very poor/poor (39% in both arms) or good/very good (61% in both arms) were the same (OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.6 to 1.4; p=0.655).

Figure 4.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of ‘understanding score’ and overall assessment score in CAT+ and no CAT arms by case

No correlation between physician experience (years as a primary care physician) and effect of CAT was found in a post-hoc analysis.

The mean consultation time in the no CAT arm was 9.7 mins compared with 9.8 mins in the CAT+ arm. The feedback provided by the actors was very similar between the no CAT and CAT+ physicians (data not shown).

Discussion

Main findings

We designed this study with the thought that the CAT may stimulate a more holistic discussion with the patient, with rapid identification of key COPD issues allowing more time for review of non-COPD aspects of the patient's condition. We found no effect of the CAT on the primary outcome, which included the ability of the physician to uncover patient issues that may not have been COPD-specific. In contrast, the CAT statistically significantly improved the assessment of standard COPD aspects (sub-score B), although the clinical relevance may be limited. Physicians in the CAT+ arm reviewed either no better or less well than those in the no CAT arm with regard to two COPD aspects (smoking and exacerbations) which are not part of the CAT but are key aspects of a COPD review. This highlights the role of the CAT as a COPD-specific assessment that complements comprehensive clinical evaluation.

This study demonstrates that the introduction of the CAT may have a specific effect. It does not raise the physician's awareness of aspects of COPD that it does not cover, nor does it ensure that clinicians are better at detecting general underlying health-related factors such as depression in a COPD patient's condition. It was perhaps optimistic to have included within the primary endpoint an assessment of physician performance that could not be improved by the CAT.

Whilst the CAT did improve COPD assessment in sub-score B, it did not improve the ‘understanding score’. One reason for this may be that 81% of physicians were judged to have acceptable or accurate assessments and only 19% were judged as poor, so there was little room for improvement. Clearly, physicians are able to form a good understanding of a patient diagnosis without the CAT, so it is unlikely to produce a large improvement in this aspect.

The objective feedback provided by the actors was very similar in the two arms, suggesting either a difference in perception of the value of the CAT between the actors and the assessors or that the questions the actors answered were not sensitive to any differences in their experience.

One area not addressed by this study is whether the CAT affected any management decisions made by the physician. This was a necessary limitation since there was no management guideline based on the CAT at the time that the study was designed. That situation has changed, and the CAT now forms part of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2011 COPD assessment framework alongside spirometry and exacerbation history.9

Throughout the study one case was seen to score better in the no CAT arm than in the CAT+ arm. This case (no. 5) was an old lady who suffered from major depression with typical symptoms such as low mood and anorexia, her COPD was poorly managed, and she was non-compliant. One might postulate that physicians in the CAT+ arm were more focused on COPD than the wider aspects of the case; however, they also scored less well in sub-score B. The presence of a disease-specific questionnaire may therefore limit the natural communication between patient and physician. Since patients with co-morbidities make up a large proportion of the COPD population seen in primary care, clinicians need to understand fully both the underlying COPD and any co-morbidities, which may require longer consultations with their physician. We interrupted those consultations still ongoing at 10 mins to maintain the real-life time pressures on primary care physicians,10 but this may have curtailed discussions unfairly.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study is the standardisation of cases and assessments to ensure a clean comparison between the arms. The study was tightly controlled, with care taken on the selection and training of the physicians, the inclusion of a pilot study to test the study design, and quality assurance activities to understand and account for the variation in scoring by individual assessors.

The artificial situation of the filming sessions could have affected the behaviours of the physicians in the study, which could have had an impact and/or limited the interpretation of the results into daily clinical practice. It is a recognised phenomenon that people improve their performance whilst being observed (Hawthorne effect). While it is not possible to eliminate this, any impact should have been similar in both arms. More importantly, the study design necessitated the interaction to be a one-off visit with no relationship or history built up between the two individuals. There was also no opportunity to evaluate the impact of the CAT on long-term management and follow-up. Interestingly, it has been noted that physicians changed their practices with experience of using the Clinical COPD Questionnaire.11 If this phenomenon is representative, the CAT may be seen to impact the physician-patient communication more over time.

Training on the CAT was provided by way of reading material and discussion between the participants in the CAT+ arm, as is often the case in real life, on the assumption that this would enable the physicians to use the CAT scores in their consultations and decision-making. It is now recognised that this approach was probably insufficient, and a more practical educational approach may have encouraged more behavioural changes in the physicians in the CAT+ arm.12 Indeed, the patient actors often reported that physicians did not refer to the CAT during the consultation.

Including the patient feedback, the assessment criteria were created specifically for this study. This is both a strength and a weakness. It allowed us to test the utility of the CAT in the areas we believed it may impact (without setting it up for guaranteed success); however, these were not tested for reliability or sensitivity. We cannot be sure whether a statistically significant difference is clinically relevant.

Physicians were selected non-randomly, and our population is certainly biased towards those with town-based practices compared with previous reports.10 This was due to the practicalities of conducting the study, where 12 physicians willing to participate in the study needed to be within travelling distance of suitable filming facilities. Rural-based physicians are likely to have similar communications skills to their urban counterparts, so we expect any bias to be reasonably small. Physicians with a specific interest or expertise in respiratory disease would have been a potential bias; to limit this, neither the recruiters nor the physicians were aware of the full nature of the study at the time of recruitment.

Our study was multinational, covering several different cultures and healthcare systems. The use of bilingual actors, who spent time with local COPD patients, allowed the cases to be portrayed with cultural accuracy. Cases were frequently played by the same actor across several countries, providing additional consistency. Similarly, assessors in Germany and the UK were used to assess physicians in Austria and Ireland, respectively. Assessor was taken as a covariate in our analysis to remove potential bias due to differences between assessors. Our study results can therefore be considered reasonably generalisable.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

To date there is no other study of the impact of the CAT on the interaction between COPD patients and their primary care physician. Indeed, to our knowledge, there are no other studies of the impact of a PROM on a single consultation in either primary or secondary care. However, a number of research projects on interventions which impact the patient-physician consultation have been published.13–20 Interventions such as encouraging patients to play a more active role in a consultation, training of practitioners in communication skills and providing more information on disease, treatment or quality of life, have been evaluated with variable success.18 One of the problems with this type of evaluation is that the methodology is not well defined and the interventions are often not clearly linked to measures of their likely effect.12,18

Implications for future research, policy and practice

We present a novel study design based on validated methodology used for assessing specialist trainees in general practice in the UK. It shows promise as a method of assessing the impact of a PROM or other tool on a consultation between a patient and the physician. However, lessons from this study would need to be considered for future use; in particular, consideration should be given to the assessment criteria that are applied. We would recommend including quality assurance activities to understand and account for variability across assessors.

This study only considers the utility of the CAT in a one-off assessment meeting. The CAT permits monitoring of the patient's COPD health status over time, but it would not be possible to run a study like this longitudinally. The CAT continues to be evaluated in different scenarios, over the mid to long term, to inform its utility and impact on long-term management and outcomes.20

Conclusions

The CAT acts as a disease-specific instrument that aids physician assessment of COPD, as it was designed to do. It does not appear to improve detection of non-COPD symptoms and co-morbidities.

Acknowledgments

Handling editor Arnulf Langhammer

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

The authors would like to thank the film crew, actors, assessors, and physicians who participated in the study, James Dodd for supporting the actor training, and the COPD patients who helped shape the study design and train the actors.

Funding Funding for this study was provided by GlaxoSmithKline.

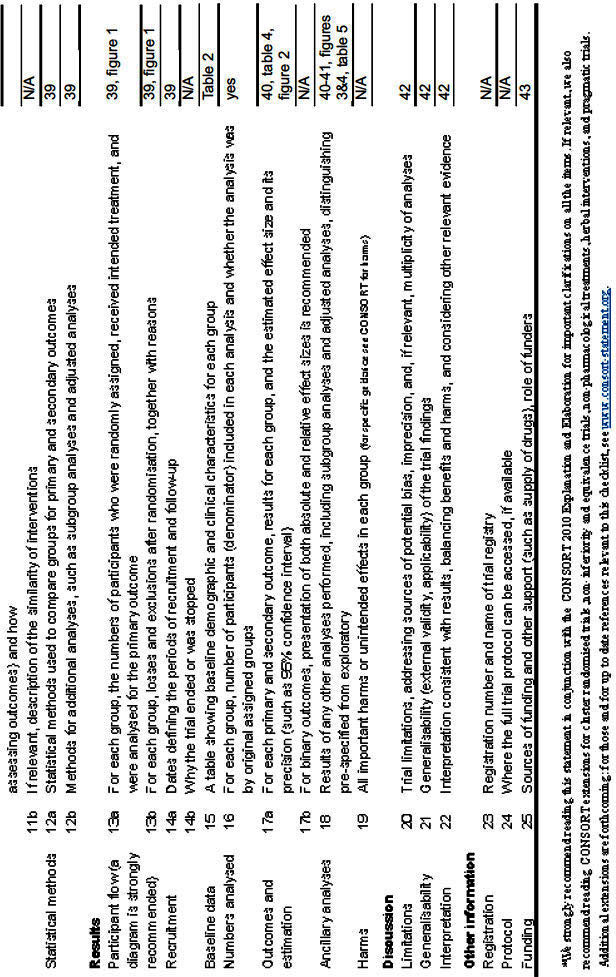

Appendix 1

Footnotes

KG-J has acted as a consultant for and spoken on behalf of GSK, AZ, Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Muni Pharma/Napp, Allmirall, Novartis, and Sandoz. SH has received speaker fees, travel grants and honoraria for advisory board from AZ, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, MSD, Napp, Novartis, and Nycomed. PK has received honoraria for advisory board, travel grants and speaker fees from AZ, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, MSD, Novartis, and Nycomed. RE has received honoraria for advisory board, travel grants and speaker fees from AZ, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, MSD, Novartis, and Nycomed. RDN has no conflict of interest in relation to this article. JR has received speaker fees, travel grants and honoraria for advisory board from AZ, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, MSD, Novartis and Teva. PJ has received fees from pharmaceutical companies including GSK for speaking at meetings and participating in advisory board meetings, and has received support for research from pharmaceutical companies including GSK. HCM, GN, MV and DAL are employees of GSK.

References

- Coulter A, Ellins J. Patient-focused interventions: a review of the evidence Picker Institute Europe; Health Foundation, 2006.

- Freeman G, Horder JP, Howie JGR, et al. Evolving general practice consultation in Britain: issues of length and context. BMJ 2002;324:880–2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7342.880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CA, Bradley CP, Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barber N. Patients’ unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;320:1246–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Harding G, Wiklund I, Berry P, Leidy N. Improving the process and outcome of care in COPD: development of a standardised assessment tool. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:208–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen W-H, Leidy NK. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Harding G, Wiklund I, et al. Tests of the responsiveness of the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Assessment Test™ (CAT) following acute exacerbation and pulmonary rehabilitation. Chest 2012. Published online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-0309

- Dodd JW, Hogg L, Nolan J, et al. The COPD assessment test (CAT): response to pulmonary rehabilitation. A multicentre, prospective study. Thorax 2011;66:425–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.156372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruffydd-Jones K, Marsden H, Holmes S, et al. Novel study design to assess the utility of the COPD Assessment Test in a primary care setting. Presented at European Respiratory Society Annual Congress, Amsterdam, 24–28 September 2011. Abstract P3764.

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2011. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/

- Deveugele M, Derese A, van den Brink-Muinen A, Bensing J, de Maeseneer J. Consultation length in general practice: cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ 2002;325:472–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7362.472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocks JWH, Kerstjens HAM, Snijders SL, et al. Health status in routine clinical practice: validity of the clinical COPD questionnaire at the individual patient level. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh J, Long A, Flynn R. The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:833–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin G, Mackay JA, Zimmermann C, et al. Clinician-patient communication: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:627–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0601-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efraimsson EO, Klang B, Larsson K, Ehrenberg A, Fossum B. Communication and self-management education at nurse-led COPD clinics in primary health care. Patient Educ Counsel 2009;77:209–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauksch LB, Dugdale DC, Dobson S, Epstein R. Relationship, communication and efficiency in the medical encounter. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1387–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.13.1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandbelt LC, Smets EMA, Oort FJ, Godfried MH, de Haes HCJM. Medical specialists' patient-centered communication and patient reported outcomes. Med Care 2007;45:330–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000250482.07970.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis N, Rollnick S, McCambridge J, Butler C, Lane C, Hood K. When smokers are resistant to change: experimental analysis of the effect of patient resistance on practitioner behaviour. Addiction 2005;100:1175–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360–0443.2005.01124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SJ, Kinmonth A-L, Veltman MWM, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:595–608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1370/afm.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LDV, Aaronson NK. Health-related Quality-of-Life assessments and patient-physician communication. A randomised controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:3027–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.23.3027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PW, Brusselle G, Dal Negro RW, et al. Properties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European study. Eur Respir J 2011;38:29–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00177210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]