Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary rehabilitation increases functional capacity and quality of life and decrease exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but there is little knowledge of how it influences their next of kin.

Aims:

To describe the experience of a multidisciplinary programme of pulmonary rehabilitation in primary health care from the perspective of the next of kin.

Methods:

A descriptive qualitative study was undertaken as part of a longitudinal study comprising a multidisciplinary programme for patients with COPD where the next of kin were invited to one session. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 next of kin and analysed by qualitative content analysis.

Results:

One main theme emerged — Life still remains overshadowed by illness. There were three sub-themes: a sense of deepened understanding; a sense of personal vulerability; and a sense of relief of burden.

Conclusions:

The next of kin's life was still overshadowed by illness, despite the multidisciplinary programme. Although experiencing positive outcomes two years after the programme, the next of kin expressed a need for more support. This study has shown that next of kin could benefit from their own participation and/or that of the patient in a multidisciplinary programme of pulmonary rehabilitation. We believe that next of kin should be offered primary health care support for the sake of their own health, but also in order to manage their informal caregiver role. The experiences described here could form a basis for further development of interventions for next of kin of patients with COPD.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nurse, primary care, rehabilitation, qualitative study

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) causes major health problems worldwide,1 and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has been shown to have beneficial effects in patients with COPD due to increasing functional capacity and quality of life in addition to reducing exacerbations.2,3 PR focuses on physical activity and includes patient education on self-management and lifestyle changes.1,4

The health status of a patient with COPD affects her/his next of kin and their life together.5,6 Previous studies have revealed that the next of kin of a patient with COPD can experience a great burden, often in combination with a lack of social support,6,7 and that sleep disorder is common.8 Strategies for managing life as a caregiver include taking care of one's own health and continuing in paid employment.9 Next of kin have described the situation as a ‘way of life’ rather than an ‘illness’ that disturbed life and considered it a health problem that they had lived with for many years.10

Positive aspects of being an informal caregiver have been described, such as sharing responsibility with the patient, thus deepening their relationship.11 However, the illness can also have a negative influence on a couple's communication, closeness, and friendship.6

Next of kin have expressed that they would like more support from the health and medical service, especially in terms of information and education about the disease.6,8 They also requested advice on how to help patients with COPD12 in order to improve their caring role.13 More specifically, some wanted more knowledge about how to handle patients' breathlessness and exacerbations as these were considered especially challenging.11 Next of kin have been described as playing a major role in assisting the patient to manage anxiety related to the illness and reducing hospitalisation.12

There is evidence that PR improves different aspects of the lives of patients with COPD.2–4 However, we have been unable to identify any research on the outcome of such education for their next of kin. As the latter experience a heavy burden and are regarded as significant for the patient's well-being, it is essential to gain knowledge of whether or not a PR programme would be of benefit to them. Such an understanding could form a basis for the future development of interventions more tailored to specifically supporting next of kin.

The aim of the present study is to describe the experience of a multidisciplinary programme of PR in primary health care (PHC) from the perspective of the next of kin. The study focuses on experiences of the patients' and next of kin's participation in the PR programme based on interviews with the latter conducted during the final session to which they had been invited together with the patient.

Methods

The study had a descriptive qualitative design and is part of a longitudinal study comprising a six-week PHC multidisciplinary programme of PR for patients with COPD to which next of kin were invited for one session. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with next of kin nominated by the patient and defined as a relative, close friend, or informal carer.

Multidisciplinary programme of PR

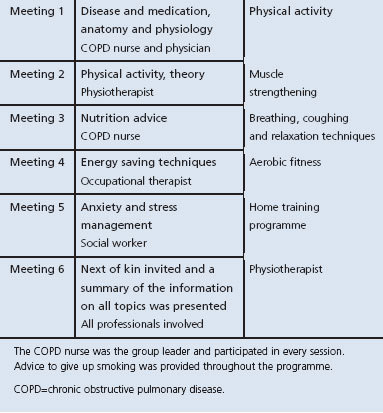

The intervention consisted of a six-week PHC multidisciplinary programme of PR for patients with COPD (Table 1). The patient outcomes have been presented in a previous study.3 Next of kin were invited to attend the final session together with the patients. The intervention took place at nine PHC centres in two Swedish county council areas during 2007 and 2008.

Table 1. Brief description of the intervention, which consisted of one hour of theory and one hour of physical activity every week.

Participants

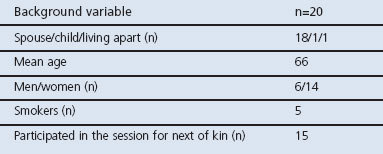

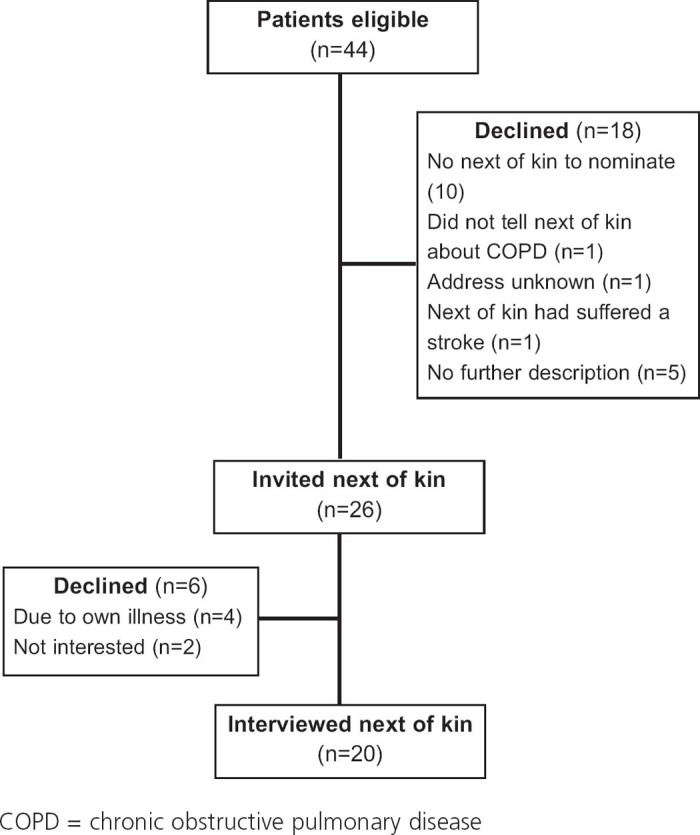

Twenty next of kin of patients diagnosed with COPD participated in this interview study (Table 2). All 44 patients with COPD, GOLD stages 2–3, who had participated in the programme received an information letter explaining the aim of interviewing next of kin. In the course of a telephone call a few days later they were asked if they had a next of kin whom they would like to nominate for the interview. Twenty-six next of kin were nominated and invited by letter to participate, of whom 20 agreed to be interviewed (Figure 1). Of these, five did not participate in the next of kin session, four because they were not informed and one due to work.

Table 2. Background of the next of kin of patients with COPD who participated in a primary health care multidisciplinary programme of pulmonary rehabilitation (n=20).

Figure 1. Participant flow.

The Regional Research Ethics Committee approved the study (No. 2009/058/1) and participants signed an informed consent form prior to the interviews.

Data collection

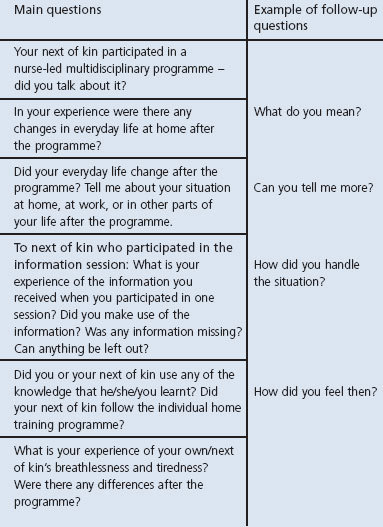

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (ABZ) in 2010. The interviews focused on next of kin's experiences of the multidisciplinary programme of PR. For those who had participated, the questions covered experiences related to their own as well as the patient's participation, otherwise they were only asked about the latter. An interview guide was used (Table 3).14 The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.14

Table 3. Description of the interview guide for next of kin.

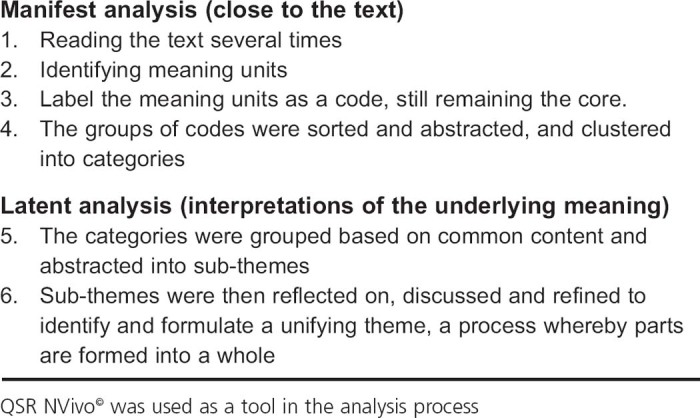

Data analysis

The interview text was analysed by qualitative content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman (Figure 2).15

Figure 2. The six steps of qualitative content analysis15.

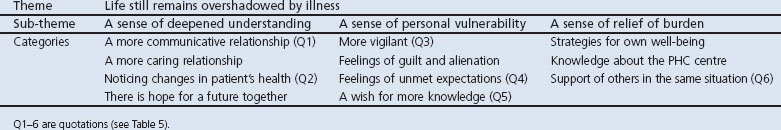

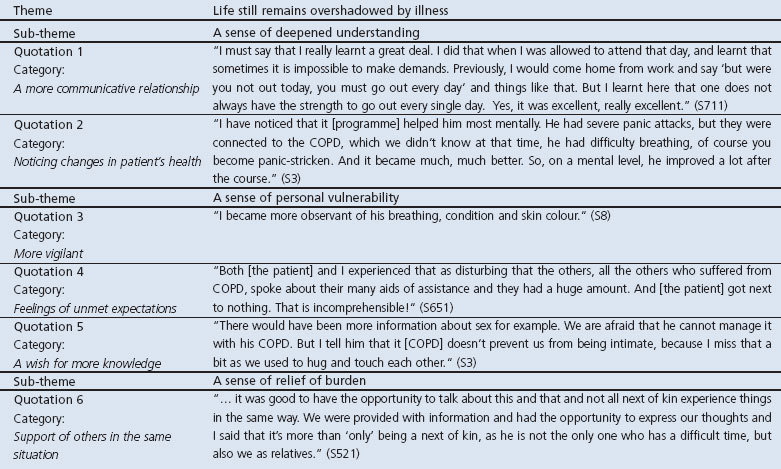

Results

The main theme — life still remains overshadowed by illness — is presented below followed by the three sub-themes: a sense of deepened understanding; a sense of personal vulnerability; and a sense of relief of burden (Table 4). Six quotations (Q1–6) that support the findings are presented in Table 5.

Table 4. Theme, sub-themes and categories.

Table 5. Quotations within the three sub-themes.

Life still remains overshadowed by illness

The latent content that emerged from the analysis of the next of kin's narratives shows that the illness still overshadowed their lives despite the multidisciplinary programme of PR. Next of kin expressed that they had expectations that the programme would make their life easier and stated that it had offered a sense of relief from the burden and a deeper understanding. However, this increased awareness could at times be experienced as burdensome as it led to a sense of personal vulnerability. They felt that the programme confirmed their experience-based strategies and that they had learnt new ones.

A sense of deepened understanding

Although their life was overshadowed by illness, the next of kin revealed that the programme gave them a positive outlook and a deeper understanding based on a sense of togetherness in their relationship.

When couples had good communication skills it was easier for next of kin to be aware of the spirit of community in their relationship and to accept the situation. The shared insight into COPD was described as strengthening the relationship; the next of kin now had a better understanding of the patient. They took care of the patient's health, tried to encourage physical activity, motivate use of the breathing technique they had learnt, prepared tasty meals, and were the ones who solved problems. Next of kin expressed that they attended the session in the programme because they had gained an understanding of the seriousness of COPD and wanted to help and support the patient (Q1, Table 5).

Next of kin noticed changes in the patient's health after the programme. When the patient used the knowledge gained through the programme, it facilitated their life together and changed the next of kin's everyday life. For example, most patients felt better when they continued practising the breathing technique they had learnt and were thereby able to exert themselves. Such improvement meant that the couple could be more active. The next of kin also experienced that the patient had benefited from meeting others in the same situation and some had stopped smoking or at least reduced the number of cigarettes. Both the next of kin and the patients felt calmer after the programme (Q2, Table 5).

The benefits of the programme made future plans more realistic. The next of kin experienced that, thanks to the programme, they could manage life together and take one day at a time. They realised that there was a future and dared to look ahead. They wanted to spend more time together with the patient as they regarded their life together as pleasant. However, some wished to obtain more support and advice about exercise for the patient to ensure that the couple could continue to undertake activities together.

A sense of personal vulnerability

Despite the programme, the next of kin felt vulnerable and that the illness had invaded their life. Some were left with unmet expectations. Their increased awareness of the disease made them more sensitive.

The next of kin expressed that they became more vigilant about the patient. Although the programme reduced their anxiety, some still experienced it occasionally. They were anxious about the patients' breathlessness, lack of strength, and what the future might hold. Some were afraid that the COPD would become worse — a fear that was confirmed at the session they attended. Several noted that the patients' health had recently deteriorated as the programme had taught them what to watch for. They reported being more vigilant and on guard. They noted changes in the patient's behaviour as well as when she/he had problems or experienced breathlessness, tiredness, sadness, and anxiety but did not ask the patient about it (Q3, Table 5).

Despite the programme, the next of kin experienced a constant need to check on the patient — for example, by phoning from work just to hear how she/he was or whether she/he had inhaled her/his medication.

The next of kin felt guilty when they themselves could not stop smoking despite the patient's attempts to stop or because they still purchased cigarettes for her/him. In some cases the patient blamed the next of kin for her/his own inability to stop smoking. Some next of kin experienced a lack of communication with the patient and a number had received no information about the session to which the next of kin were invited. One patient did not discuss the programme and her/his next of kin had no opportunity to share the knowledge gained and felt alienated.

A few next of kin thought that the programme had a negative influence on the patient in terms of less physical activity. Others considered it pointless as they could see no change and the patients were still breathless and tired, so the knowledge obtained appeared to be of little use. The next of kin therefore had an impression of unmet expectations. Some saw no value in meeting others in a similar situation and claimed that they learnt nothing from the programme. Furthermore, they were disappointed that the health and medical service did not do more to encourage the patient to stop smoking or provide aids of assistance (Q4, Table 5).

However, some next of kin wanted more information about COPD and how they could be of assistance in the future. Others were satisfied with the information received but would have liked to know more about additional topics such as sexual aspects (Q5, Table 5).

A sense of relief of burden

The next of kin described how the programme provided some strategies for coping with their often burdensome situation.

The programme made the next of kin aware of the importance of prioritising time for themselves to manage the situation. Some took care of their health, trained every day, and ensured that they had sufficient sleep. At times the next of kin used strategies such as ignoring the problem and not brooding about the fact that the patient had COPD; they were of the opinion that the patient was the healthiest participant in the programme.

After the programme the next of kin gained a sense of security thanks to the PHC centre, as knowing that there was someone else who cared for the patient made them feel less lonely. Meeting others in the same situation was deemed supportive (Q6, Table 5). The next of kin were of the opinion that all those affected by COPD should be offered the opportunity to participate in a COPD programme.

Discussion

Main findings

The main finding in the present study was that two years after the PHC multidisciplinary programme of PR, the next of kin's perspective was that life remained overshadowed by illness. They reported both a sense of deeper understanding and togetherness with the patient as well as vulnerability due to the intrusion of the illness in their lives. After two years they still remembered and used the knowledge they had obtained, felt calmer, did not worry as much, had developed strategies to handle the situation, and a sense of being relieved of burden.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Credibility, dependability, and transferability are aspects of trustworthiness that strengthen the study. Credibility was demonstrated by providing information about sampling, data collection strategies and analysis technique, and by presenting relevant quotations. Dependability was strengthened by using an interview guide and a software analysis tool, making it easier to move between the raw data and the emerging categories and themes. While the findings of qualitative studies cannot be generalised, they can be transferred to provide increased understanding of similar situations in a new context, based on the study setting and the information provided by the participants.14,16

One limitation of the study design is that the period of approximately two years that elapsed between the programme and the interview is a relatively long period. It can be difficult for the next of kin to distinguish between the outcomes of the programme and changes caused by time and other factors. Their recollection might have had been better if the interviews had been performed shortly after the programme. On the other hand, the time lapse may have made the longitudinal effects more visible. Had the interviews been conducted in conjunction with the completion of the programme, it would have been impossible to identify any long-term experiences although immediate perceptions would have been easy to capture.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

In line with previous studies,6,7 the next of kin in the present study felt vulnerable and that the illness had invaded their lives. Nevertheless, the programme made them aware of the importance of prioritising time for themselves in order to manage the situation. Some consciously and proactively took care of their own health, which is also in line with previous studies.11 In the present study deeper understanding, togetherness, and a more communicative relationship were described as a result of the programme. This is somewhat contrary to previous findings, where it was revealed that the illness could have a negative influence on the couple's communication, closeness, and friendship.6 We do not know whether the positive experiences reported by the participants are solely related to their participation in one session, the patient's participation, a combination of both, or contextual factors.

The next of kin wanted more knowledge about COPD. Another study found that breathlessness was particularly challenging and that the next of kin had no strategies for managing it. They were also poorly prepared for acute exacerbations.11 It is essential to take the deficit in COPD knowledge into account when planning support for next of kin. As they can be thrown between having a patient in a stable state followed by acute situations with breathlessness, anxiety and exacerbations, they might need more ‘just-in-case’ knowledge in order to be prepared for such events. The next of kin seemed to require help to increase their confidence and self-efficacy in order to successfully perform support activities. Meleis17 is of the opinion that one of the roles of nurses is to maximise the next of kin's strengths, assets and potential, or to contribute to the restoration of optimal levels of health, functioning, comfort, and self-fulfilment. Health promotion is also the task of the COPD nurse in PHC.18 As the next of kin's contribution to the care is associated with positive effects for the patient,12 we believe that supporting the next of kin should be a priority issue in PHC.

The next of kin wanted more support — on the one hand, more knowledge about how to handle COPD and, on the other, increased support for themselves. The programme seemed to have left the next of kin with a sense of being both weaker and stronger; they became afraid that the COPD would become worse while, at the same time, it left them with a sense of being relieved of the burden. The findings indicate that it is not sufficient to merely educate the patient with COPD and invite her/his next of kin to one session, but that other strategies are necessary. A psycho-educational intervention that might be effective is Powerful Tools for Caregivers (PTC), which can be used to reduce the distress and objective burden among next of kin who care for disabled partners.19 PTC is based on Bandura's self-efficacy theory.20 We believe it would be valuable to support next of kin at an earlier stage, as suggested in a previous study.13

Some next of kin felt that the programme had a negative influence on the patient in terms of less physical activity. One possible reason could be that the patients had difficulty understanding the contradictory advice provided by the occupational therapist and the physiotherapist. The former argued for energy saving techniques while the latter stated that patients needed physical activity to manage their disease. Previous research has indicated that breathlessness is the greatest problem for patients with COPD; it creates a fear of physical activity21,22 and gives a negative activity spiral.23,24 This could be the reason why patients engaged in less physical activity and failed to comply with the instructions given during the programme.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

This study revealed that next of kin could benefit from their own as well as the patient's participation in a multidisciplinary programme of PR, despite the fact that some needs and expectations were not met by the present programme. Based on the findings, we believe that next of kin should be offered primary health care support for the sake of their own health and also in order to manage their informal caregiver role. The experiences described here could form the basis for further development of interventions for the next of kin of patients with COPD. Next of kin would probably benefit from a more tailored intervention designed to meet their specific needs or from participating in the whole programme together with the patient.

It would be valuable to perform interviews in conjunction with the conclusion of a PR programme in order to gain more knowledge about the short-term perceptions related to such a programme. A follow-up with a quantitative design — for example, questionnaires — could be used to measure long-term outcomes in a broader population.

Conclusions

Despite the programme, the next of kin felt that their lives were overshadowed by the illness. Although somewhat insufficient in relation to their needs and expectations, the programme had positive outcomes for next of kin at the two-year follow-up. It enabled the couples to talk about the difficulties, and the next of kin sensed greater togetherness in the relationship as well as a relief in their personal burden.

Acknowledgments

Handling editor Maureen George

We would like to thank all the patients and next of kin who participated as well as the teams that made the previous intervention study possible. We would also like to express our gratitude to research administrator Susanne Collgård for transcribing the interviews and Professor Peter Engfeldt at the Family Medicine Research Centre and Associate Professor Doris Hägglund at the School of Health and Medical Sciences, Örebro University for discussions about the design of the study.

Funding This research was funded by the Foundation of Maja Johansson and the Maria Brantefors scholarship fund in Örebro University for developmental work in the area of health and medical services.

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

References

- GOLD. Executive Summary: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD. NHLBI/WHO workshop report; 2013. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com.

- Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003793. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zakrisson AB, Engfeldt P, Hagglund D, et al. Nurse-led multidisciplinary programme for patients with COPD in primary health care: a controlled trial. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20(4):427–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATS/ERS. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173(12):1390–413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200508-1211ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a phenomenological study of patients' experiences. J Clin Nurs 2005;14(7):805–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamark DA, Blake SD, Seamark CJ, Halpin DM. Living with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): perceptions of patients and their carers. An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Palliat Med 2004;18(7):619–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269216304pm928oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson AC, Young J, Donahue M, Rocker G. A day at a time: caregiving on the edge in advanced COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010;5:141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergs D. “The Hidden Client” — women caring for husbands with COPD: their experience of quality of life. J Clin Nurs 2002;11 (5):613–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Reconciling employment with caring for a husband with an advanced illness. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-2166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock H, Kendall M, Murray SA, et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011;342:d142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels MH, Higginson IJ. Caring for a person in advanced illness and suffering from breathlessness at home: threats and resources. Palliat Support Care 2009;7(2):153–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1478951509000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caress A, Luker K, Chalmers K. Promoting the health of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: patients' and carers' views. J Clin Nurs 2010;19(3–4):564–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caress AL, Luker KA, Chalmers KI, Salmon MP. A review of the information and support needs of family carers of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs 2009;18(4):479–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02556.xx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. London: Sage, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24(2):105–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, California, USA: Sage, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Meleis AI. Theoretical nursing: development and progress. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Svensk Sjuksköterske Förening. Kompetensbeskrivning för legitimerad sjuksköterska med specialistsjuksköterskeexamen, Distriktssköterska. Svensk Sjuksköterskeförening; 2008 (cited 20 June 2011). Available from: www.swenurse.se

- Savundranayagam MY, Montgomery RJ, Kosloski K, Little TD. Impact of a psychoeducational program on three types of caregiver burden among spouses. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26(4):388–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gps.2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: WH Freeman and Co, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Arne M, Emtner M, Janson S, Wilde-Larsson B. COPD patients perspectives at the time of diagnosis: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2007;16(4):215–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2007.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels M, Higginson IJ. The experience of breathlessness: the social course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39(3):555–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Nicotra B, Clark L, et al. Exercise conditioning in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1988;69(2):118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo K. A pilot study to examine the relationships of dyspnoea, physical activity and fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs 2000;9(4):526–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]