Abstract

Foot drop is very common among people with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI) and likely stems from SCI that disturbs the corticospinal activation of the ankle dorsiflexor tibialis anterior (TA). Thus, if one can recover or increase the corticospinal excitability reduced by SCI, motor function recovery may be facilitated. Here, we hypothesized that in people suffering from weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI, increasing the TA motor-evoked potential (MEP) through operant up-conditioning can improve dorsiflexion during locomotion, while in people without any injuries, it would have little impact on already normal locomotion. Before and after 24 MEP conditioning or control sessions, locomotor electromyography (EMG) and kinematics were measured. This study reports the results of these locomotor assessments. In participants without SCI, locomotor EMG activity, soleus Hoffmann reflex modulation, and joint kinematics did not change, indicating that MEP up-conditioning or repeated single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (i.e., control protocol) does not influence normal locomotion. In participants with SCI, MEP up-conditioning increased TA activity during the swing-to-swing stance transition phases and ankle joint motion during locomotion in the conditioned leg and increased walking speed consistently. In addition, the swing-phase TA activity and ankle joint motion also improved in the contralateral leg. The results are consistent with our hypothesis. Together with the previous operant conditioning studies in humans and rats, the present study suggests that operant conditioning can be a useful therapeutic tool for enhancing motor function recovery in people with SCI and other central nervous system disorders.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study examined the functional impact of operant conditioning of motor-evoked potential (MEP) to transcranial magnetic stimulation that aimed to increase corticospinal excitability for the ankle dorsiflexor tibialis anterior (TA). In people with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI), MEP up-conditioning increased TA activity and improved dorsiflexion during locomotion, while in people without injuries, it had little impact on already normal locomotion. MEP conditioning may potentially be used to enhance motor function recovery after SCI.

Keywords: foot drop, locomotor electromyography, operant conditioning, tibialis anterior, transcranial magnetic stimulation

INTRODUCTION

Foot drop is one of the most common and disabling impairments among the people with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI) (van Hedel et al. 2005). This problem of weak ankle dorsiflexion likely stems from SCI that disturbs the corticospinal activation of the ankle dorsiflexor tibialis anterior (TA), which is essential during walking (Petersen et al. 2010, 2012). In people with no known neurological injuries, corticospinal excitability for the TA, measured in the motor-evoked potential (MEP) amplitude to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), is high before and during the swing phase of walking (Capaday et al. 1999; Schubert et al. 1997). In contrast, in people with SCI, TA MEPs are often small, indicating reduced corticospinal excitability and connectivity (Brouwer and Hopkins-Rosseel 1997; Calancie et al. 1999; Davey et al. 1999; McKay et al. 2005; van Hedel et al. 2007), which would explain, at least partly, frequent occurrence of foot drop in this population (Barthélemy et al. 2010; van Hedel et al. 2005; Wirth et al. 2008a, 2008b).

If the loss of corticospinal excitability contributes to impaired motor function, then can the recovery or increase of corticospinal excitability facilitate motor function recovery? Currently available studies support such a possibility. Even in the chronic stage of injury, MEP amplitude increases as motor function improves in response to constraint-induced therapy (Liepert et al. 1998, 2000a, 2000b), partial body weight supports treadmill training (Thomas and Gorassini 2005), and functional electrical stimulation (Everaert et al. 2010; Stein et al. 2006). Thus, the underlying hypothesis of the present study is that increasing the corticospinal excitability can improve motor function that relies on the activity of corticospinal pathways.

Operant conditioning of stimulus-induced muscle responses (e.g., reflexes) can induce plasticity in the targeted neural pathway (Wolpaw 2010; Thompson and Wolpaw 2014, 2015). Based on the encouraging findings in rats with partial SCI (Chen et al. 2006), several years ago, operant conditioning of the soleus Hoffmann reflex (H-reflex) was investigated in people with chronic incomplete SCI. Studies found that down-conditioning can decrease H-reflex size in spastic people whose H-reflex is large due to SCI and can improve their walking (Manella et al. 2013; Thompson et al. 2013). Here, we used an operant conditioning approach to increase MEP size that reflects corticospinal excitability. Specifically, we hypothesized that increasing the TA MEP through operant up-conditioning in sitting can improve dorsiflexion during the swing-to-swing stance transition phase of locomotion and alleviate foot drop in people with SCI. At the same time, in people without SCI or any other known neurological conditions we anticipated little impact of MEP up-conditioning on already normal locomotion, as it was the case for soleus H-reflex down-conditioning (Makihara et al. 2014).

To test the hypothesis, participants with and without SCI were exposed to an operant up-conditioning protocol to increase the size of TA MEP or a control protocol with which TA MEPs were simply elicited (Thompson et al. 2018a). Before and after 24 conditioning/control sessions, locomotor electromyography (EMG) and kinematics were measured. For each participant, to determine whether MEP up-conditioning was successful or MEP control protocol affected MEP size, the average MEPs of the final six conditioning/control sessions were compared with the average MEPs of the six baseline sessions (Thompson et al. 2009a, 2013, 2018a). In five of eight conditioning participants without SCI, MEP size increased to 150 ± 13% (SD) of baseline value (Thompson et al. 2018a). In the other three conditioning participants, the MEP did not increase significantly. In all control participants without SCI, MEP size did not change. In nine of 10 conditioning participants with SCI, MEP size increased to 151 ± 4 % (SD) of baseline value (Thompson et al. 2018a). To examine whether increasing the TA MEP through operant up-conditioning affects locomotion, this study reports the results of locomotion assessments from the conditioning group of individuals without SCI in whom MEP up-conditioning was successful (n = 5), the control group of individuals without SCI (n = 7), and the conditioning group of individuals with SCI in whom MEP up-conditioning was successful and whose measurements could be made (n = 7), and discusses functional impact of MEP conditioning in people with normal gait and in people with weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI. We acknowledge that a lack of control group with SCI would limit the interpretation of the present results; because the study was conducted along the initial investigation of MEP operant conditioning to examine its feasibility (Thompson et al. 2018a), a control group of individuals with SCI were not available for this study. Partial preliminary analyses of these data have been reported in a conference proceeding (Thompson et al. 2016).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Participants and Overview

Healthy adults with and without chronic incomplete SCI completed the MEP operant conditioning protocol as approved by the Institutional Review Board of Helen Hayes Hospital, New York State Department of Health, and the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of South Carolina. All participants gave written consent before participation.

Fifteen adults (5 men and 10 women, aged 30 ± 8 (SD years) with no known neurological conditions were exposed to either the conditioning protocol that consisted of six baseline sessions and 24 conditioning sessions (i.e., conditioning group, n = 8) or the control protocol that consisted of six baseline sessions and 24 control sessions (i.e., control group, n = 7). Ten adults [7 men and 3 women, aged 49 ± 11 (SD) years] with well-defined stable impairment of weak ankle dorsiflexion due to a spinal cord lesion were exposed to the conditioning protocol (i.e., 6 baseline + 24 conditioning sessions). The profiles of participants with SCI are summarized in Table 1. As described in Thompson et al. (2018a), a physiatrist or a neurologist determined participation eligibility for each prospective individual with SCI. Inclusion criteria for individuals with SCI were: 1) neurologically stable (>1 yr post-SCI); 2) medical clearance to participate; 3) ability to ambulate at least 10 m with or without an assistive device (e.g., walker, cane, and crutches); 4) signs of weak ankle dorsiflexion at least unilaterally (i.e., manual muscle strength test score < 5); and 5) expectation of no medication change at the time of study enrollment. Stable use of anti-spasticity medication was permitted. Exclusion criteria were: 1) motoneuron injury; 2) known cardiac condition (e.g., history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pacemaker use); 3) medically unstable condition; 4) cognitive impairment; 5) a history of epileptic seizures; 6) metal implants in the cranium; 7) implanted biomedical device in or above the chest (e.g., a cardiac pacemaker, cochlear implant); 8) no measurable MEP elicited in the TA; 9) unable to produce any voluntary TA EMG activity; and 10) use of functional electrical stimulation to the leg on a daily basis. In participants with bilateral weakness of ankle dorsiflexors in whom a TA MEP could be elicited in both legs, the more severely impaired leg was studied. In participants with unilateral dorsiflexor weakness or in participants with bilateral weakness in whom a TA MEP could be elicited in only one leg, that leg was studied. Note that in the individuals in whom locomotor joint motion could be measured, the conditioned leg’s ankle angle at foot contact was significantly less (more plantarflexed) than the participants without SCI, before undergoing MEP conditioning (P = 0.001, by unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test).

Table 1.

Profiles of study participants with chronic incomplete SCI

| Patient | Age (yr) | Gender | Cause | SCI Level | AIS | Years Post- SCI | Baclofen | TA MEP latency (ms) | Baseline MEP size (%Mmax) | Final MEP size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | F | NT | T12 | D | N/A* | Yes | 32 | 10.0 | 136.0 |

| 2 | 52 | M | T | C5 | D | 3 | No | 40 | 9.9 | 157.0 |

| 3 | 29 | M | T | C7 | C | 6.5 | No | 37 | 1.7 | 151.7 |

| 4 | 67 | M | NT | T5 | D | 10 | Yes | 42 | 16.7 | 135.0 |

| 5 | 45 | M | T | C4 | D | 10 | Yes | 37 | 7.1 | 161.2 |

| 6 | 47 | M | T | C4 | C | 4 | Yes | 41 | 20.9 | 174.1 |

| 7 | 42 | M | T | C4 | D | 1.5 | Yes | 44 | 1.1 | 153.6 |

| 8 | 54 | M | T | C6 | D | 10 | No | 44 | 10.1 | 147.4 |

| 9 | 55 | F | NT | C6 | D | 5.5 | No | 36 | 2.3 | 143.8 |

| 10 | 39 | F | T | C4 | C | 6 | Yes | 32 | 10.7 | 99.1 |

Tibialis anterior (TA) motor-evoked potential (MEP) latency was determined during the baseline sessions as shown. Baseline MEP size: average MEP size for the six baseline sessions, in each 225 controls MEPs were elicited at 10–15% above the active motor threshold. Final MEP size is calculated as the average of conditioning sessions 22–24 (Thompson et al. 2018a) and expressed as %baseline value. SCI, spinal cord injury. Cause, cause of spinal cord damage (T, trauma, NT, nontrauma). AIS, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale.

Cannot be determined due to her diagnosis (hereditary spastic paraparesis).

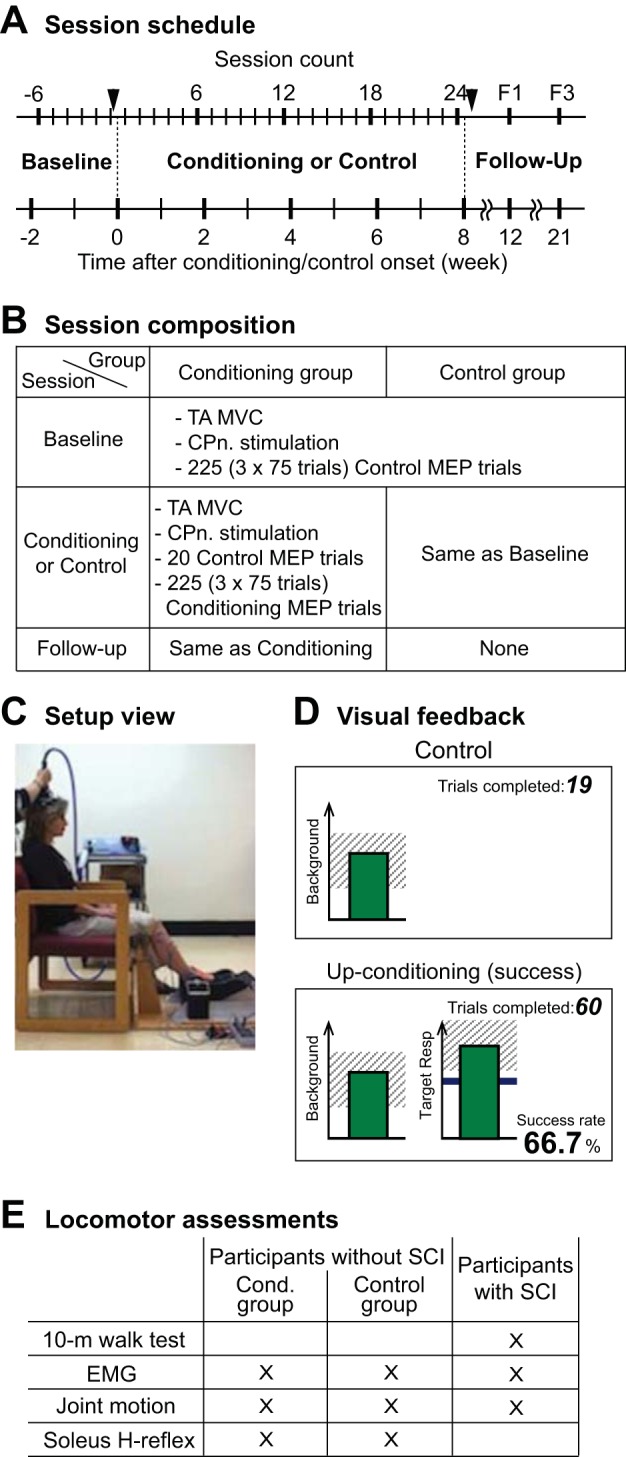

Each participant completed six baseline sessions and 24 up-conditioning or control sessions that occurred at a pace of three times per week. In all participants with no known neurological conditions, locomotor EMG, soleus locomotor H-reflex, and ankle, knee, and hip joint motion were measured before and after 24 up-conditioning or control sessions. In all participants with chronic stable incomplete SCI, 10-m walking speed was measured before and after 24 up-conditioning sessions. In seven participants with SCI locomotor EMG and ankle, knee, and hip joint motion were measured before and after 24 up-conditioning sessions. These measurements could not be made with three participants with SCI (identified as 1, 6, and 10 in Table 1) whose gait was severely limited before conditioning. Locomotor soleus H-reflex was not measured in participants with SCI, as its procedure typically requires >400 steps with or without tibial nerve stimulation. In individuals with SCI whose ambulatory capacity is limited, collecting such a large number of steps without fatigue affecting the quality of step performance and EMG signal is difficult. Thus, in this study, we focused on collecting locomotor EMG data >50 steps from the majority of the participants with SCI. General study session schedule and timing of locomotor assessments are displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overall study protocol. A: study session schedule. Six baseline sessions are followed by 24 conditioning or control sessions and then by two follow-up sessions. Before and after 24 conditioning or control sessions (indicated by arrowheads), locomotion assessments, including electromyography (EMG) and kinematics, were done in all participants. B: composition of baseline, conditioning, and control sessions. Isometric maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) was measured as the tibialis anterior (TA) EMG amplitude. Common peroneal nerve (CPn) stimulation was for the maximum M-wave and Hoffmann reflex (H-reflex) measurements. C: setup view. Motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) were measured while the participant sat in a chair with ankle, knee, and hip angles fixed at ≈ −10°, ≈60°, and ≈70° in a custom-made apparatus. D: visual feedback screens for control and conditioning trials. In all trials, the number of the current trial within its block is displayed, and the background EMG panel shows the correct range (shaded) and the current value (green vertical bar, updated every 200 ms). If TA EMG activity stays in the correct range for at least 2 s and at least 5.5 s has passed since the last trial, a MEP is elicited. In control trials (left), the MEP panel is not shown. In conditioning trials (right), the shading in the MEP panel indicates the rewarded MEP range for up-conditioning (Resp, response). The dark horizontal line is the average MEP size of the baseline sessions, and the vertical bar is the MEP size (i.e., the mean rectified EMG in the MEP interval (determined for each individual participant) for the most recent trial (it appears 200 ms after TMS). If that MEP size reaches into the shaded area, the bar is green, and the trial is a success. If it falls below the shaded area, the bar would be red, indicating the trial is a not a success. The running success rate for the current block is shown, bottom. E: list of measurements made for locomotor assessments for each group of participants.

MEP Conditioning Protocol

The MEP operant conditioning protocol has been described in detail elsewhere (Thompson et al. 2018a), and only briefly summarized here. After being familiarized with the TMS procedures performed using Magstim 200−2 and a custom-made double-cone coil (in participants with SCI) or a bat-wing coil (in participants without SCI) with radii of 9 cm (Jali Medical, Woburn, MA) and EMG procedures in a few preliminary sessions, each participant completed six baseline sessions and 24 up-conditioning or control sessions that occurred at a pace of three times per week. To avoid variability due to possible diurnal variation in response size (Lagerquist et al. 2006; Tamm et al. 2009), each individual’s sessions always occurred at the same time of day (i.e., within the same 3-h time window). Figure 1A summarizes the study session schedule.

At the beginning of each session, self-adhesive surface Ag-AgCl electrodes were placed over the muscle bellies of TA and soleus for EMG recording (Thompson et al. 2009b, 2011). The EMG signal was amplified, band-pass filtered (10–1000 Hz), and sampled at 3,200 Hz. After the TA maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVC) measurement and common peroneal nerve (CPn) stimulation to measure the TA H-reflex/M-wave recruitment curve measurement, control MEPs were elicited while the participant sat in a chair with ankle, knee, and hip joints fixed at ≈ −10° (i.e., 10° plantarflexed), ≈60°, and ≈70°, respectively (see Fig. 1C), and produced the preset level of stable TA background EMG activity. This preset level of TA background EMG was ≈15% MVC level for participants without SCI and ≈30–35% MVC level for individuals with SCI, determined during the preliminary sessions and maintained the same throughout the study. For all MEP trials, the same absolute TMS intensity, 10–15% above active threshold that was determined during the preliminary sessions was used throughout the study. In participants without SCI, this TMS intensity was 51 ± 9% (SD) (range 35–65%) maximum stimulator output, and in participants with SCI, it was 62 ± 12% (range 45–82%) maximum stimulator output. TA and soleus background EMG levels were kept stable throughout data collection.

In each baseline session (in both control and conditioning group) and each control session (in control group), 225 (3 blocks of 75 trials) control MEP trials were performed. In each conditioning session (in conditioning group), 20 control MEP trials and 225 (3 blocks of 75 trials) conditioning MEP trials were performed. For all control trials, MEPs were elicited with no feedback on MEP size. For 225 conditioning trials of each conditioning session (i.e., in conditioning group), the participant was encouraged to increase TA MEP size, and received immediate feedback as to whether MEP size was above a criterion (i.e., whether the trial was a success) (Fig. 1D). The MEP feedback bar on the screen, which would flash 200 ms after each stimulus, became green if MEP size was larger than the criterion, and the bar became red if MEP size was smaller than the criterion. The criterion was based on the average MEP size for the previous block of trials. In each conditioning session, the criterion value for the first block of 75 conditioning trials was determined based on the immediately preceding block of 20 control trials, and the criterion values for the second and third conditioning blocks were based on the immediately preceding block of 75 conditioning trials. The criterion was selected so that if MEP values for the new block were similar to those for the previous block, 50–60% of the trials would be successful (Chen and Wolpaw 1995; Thompson et al. 2009a). For each block, the participant earned a modest extra monetary reward if the success rate exceeded 50%. (See Thompson et al. 2009a for full details of protocol.)

Stability of Background EMG, TA M-Wave, and TA H-Reflex

In both the control and conditioning groups of participants without known neurological conditions and in participants with SCI, the TA maximum M-wave (Mmax) and maximum H-reflex (Hmax), and TA and soleus background EMG levels (calculated as the mean absolute amplitude in a prestimulus period of 50 ms) in control and conditioning MEP trials remained stable throughout the study (Thompson et al. 2018a). TA Mmax and Hmax remained within ±10% of the baseline average across all the sessions. For participants without SCI, the peak-to-peak Mmax and Hmax were 4.55 ± 0.60 (mean ± SE) mV and 0.43 ± 0.07 mV during the baseline sessions and 4.64 ± 0.62 mV and 0.41 ± 0.06 mV for the last six conditioning/control sessions (i.e., conditioning/control sessions 19–24), respectively. For individuals with SCI, the Mmax and Hmax were 2.90 ± 0.45 (mean ± SE) mV and 0.66 ± 0.37 mV during the baseline sessions and 3.08 ± 0.47 mV and 0.66 ± 0.34 mV for the last six conditioning sessions, respectively. For these Mmax values, the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.99 for six baseline sessions and 0.99 for the last six conditioning sessions, and the intraclass correlation coefficient between the six baseline sessions and the last six conditioning sessions was also 0.99, indicating highly reproduceable preparation and placement of EMG recording and stimulating electrodes across the sessions. TA background EMG remained within ± 10% of the baseline average across all the sessions. For participants without SCI, TA background EMG (aimed at ≈15% MVC level) was 47 ± 4 μV (mean ± SE) [5.2 ± 0.4% Mmax (mean ± SE)] during the baseline sessions and 48 ± 4 μV (4.9 ± 0.3% Mmax) for the last six conditioning/control sessions. For individuals with SCI, TA background EMG (aimed at ≈30–35% MVC level) was 29 ± 6 μV (5.6 ± 1.8% Mmax) during the baseline sessions and 30 ± 5 μV (5.4 ± 1.8% Mmax) for the last six conditioning/control sessions. Soleus background EMG remained within the resting EMG level (i.e., <8 µV) throughout the study in all participants. TA MVC did not change across the sessions in the control and conditioning groups of participants without SCI (remained within ±10% of the baseline average throughout the study) and increased insignificantly in participants with SCI by ≈12% over the course of study. In all three groups, F-values for these parameters evaluated by one-way repeated measures ANOVA were 0.4–2.0, with P values of 0.12–0.97. These results support that the EMG recording and nerve stimulation conditions did not change systematically over the course of study.

Locomotor Assessments

10-m walk test.

In all participants with SCI, 10-m walking speed was measured before and after 24 up-conditioning sessions. Each participant was asked to walk at his/her fastest comfortable speed from the 0-m marker to the 14-m marker. Speed was only calculated for the 10-m distance between the 2- and 12-m markers; that is, timing starts when the toes of the leading foot cross the 2-m marker and stops when the toes of the leading foot cross the 12-m marker. Assistive devices (e.g., cane and walker) were permitted, and were kept the same in each participant over the study. Three trials were averaged together to calculate the 10-m speed for each assessment.

Locomotor EMG and joint motion measurement.

In all participants without SCI and seven of 10 participants with SCI, locomotor EMG activity and kinematics were measured while the participants walked on the treadmill or overground at their comfortable speeds. For the ones who walked on the treadmill, the same speed was used for the measurements before and after the 24 conditioning/control sessions. For three individuals with SCI whose initial walking speed was >0.15 m/s, these measurements were not made. The participants with SCI who wore an ankle foot orthosis were asked to remove it for these measurements.

Surface EMG was obtained from TA, soleus, biceps femoris (BF), and vastus lateralis (VL), bilaterally with self-adhesive Ag-AgCl electrodes (2.2 × 3.5 cm, 2.2 × 3.5 cm, Vermed, Bellows Falls, VT), amplified, 10–1,000 Hz band-pass filtered, digitized at 4,000 Hz, and stored. For detecting foot contact and toe off of each leg, foot switch cells were inserted between the participant’s shoes and feet. The participants who were capable of and comfortable with ≈5 min of treadmill walking (i.e., all participants without SCI and five participants with SCI) walked on the treadmill for 3–4 min with the safety body harness on. In two participants with SCI who were not comfortable with treadmill walking, 10 m overground walking was repeated several times to collect ≥50 steps. The participants were allowed to sit down to take a break as needed between these overground walking measurements. Immediately before or after the locomotor EMG measurement, the CPn was stimulated to obtain the TA recruitment curve while the participant sat in a chair with ankle, knee, and hip joints fixed at ≈ −10°, ≈60°, and ≈70°, respectively, as in the baseline/conditioning/control session.

Following locomotor EMG, the ankle, knee, and hip joint motions were measured during overground walking, using a 3-D motion capture system (Vicon Motion Systems, Centennial, CO). Small retro-reflective markers were attached to landmarks on the subject’s body, to capture the lower limb and joint motions accurately in the 3D coordinates. Specifically, the markers were placed at the toe (head of first metatarsal), fifth metatarsal (head), ankle (lateral malleolus), heel, knee (lateral epicondyle), hip (great trochanter), anterior superior iliac spine, posterior superior iliac spine, lateral thigh, and lateral lower leg (over peroneal longus), bilaterally. Positions of the markers were tracked while the subject walked across the capture volume a number of times. More than 50 steps were averaged together to characterize each participant’s locomotion before and after the 24 conditioning/control sessions. In two individuals with SCI, in whom the marker-tracking system could not capture the joint motion effectively, an electrogoniometer system (Biometrics, Ladysmith, VA) was used to obtain joint angle data in the sagittal plane: dorsiflexion/plantarflexion for the ankle and flexion/extension for the knee and hip.

Soleus H-reflex measurement.

Before and after the 24 conditioning/control sessions, the soleus H-reflex was measured in all participants without SCI. To elicit the H-reflex, the tibial nerve was stimulated in the popliteal fossa, using surface Ag-AgCl electrodes (2.2 × 2.2 cm for the cathode and 2.2 × 3.5 cm for the anode; Vermed) and a Grass S48 stimulator (with a CCU1 constant current unit and an SIU5 stimulus isolation unit; Natus Neurology Grass, Warwick, RI). The stimulating electrode pair was placed to minimize the H-reflex threshold and to avoid stimulating the CPn. Immediately before the locomotor H-reflex measurement, the soleus H-reflex/M-wave recruitment curve was obtained while the participant maintained a natural standing posture with stable levels of soleus and TA background EMG activity; typically, the soleus background EMG level corresponded to 10–20% of a maximum voluntary contraction (Makihara et al. 2014; Thompson et al. 2009a), and the TA level was <7 μV absolute value (i.e., resting level). Single 1-ms square pulses were delivered to the tibial nerve with the minimum interstimulus interval of 5 s. Stimulus intensity was varied in increments of 1.25–2.50 mA from below soleus H-reflex threshold, through the intensity that elicited the maximum H-reflex (Hmax), to an intensity just above that needed to elicit the maximum M-wave (Mmax) (Kido et al. 2004a; Makihara et al. 2012). About 10 different intensities were used to obtain each recruitment curve. At each intensity, four EMG responses were averaged to measure the H-reflex and M-wave. Based on this recruitment curve measurement, the stimulus intensity for the subsequent locomotor H-reflex measurements was selected such that it fell on the rising phase of the H-reflex recruitment and produced an M-wave above threshold.

To evaluate phase-dependent modulation of the H-reflex (Capaday and Stein 1986; Ethier et al. 2003; Kido et al. 2004a; Makihara et al. 2012; Schneider et al. 2000; Stein and Capaday 1988), single 1-ms square pulse stimuli were delivered to the tibial nerve at different times of the step cycle. The stimulus interval was set to be long enough to have at least one full unstimulated step between stimuli.

Analysis of locomotor EMG, kinematics, and H-reflex.

For the analysis of locomotor EMG, joint motion, and reflex, foot-contact was used to define the beginning of the step cycle. EMG signals from individual steps were normalized to the mean step cycle time and averaged together to obtain the locomotor EMG activity over the step cycle (Kido et al. 2004b; Makihara et al. 2012, 2014; Thompson et al. 2013). For quantitative analysis, the step cycle was divided into 12 equal bins and EMG activity was averaged for each bin. For each participant’s each muscle, the average rectified EMG amplitude for each of the 12 bins was expressed in percentage of the amplitude in the bin with the highest amplitude. To evaluate the extent of EMG modulation during locomotion, the modulation index (MI) was calculated in percent as: 100 × [(highest bin amplitude − lowest bin amplitude)/highest bin amplitude] (Zehr and Kido 2001; Zehr and Loadman 2012). To quantify the amount of swing-phase TA activity in the leg that was conditioned (or stimulated, for the control participants), the values for bins 8–12 were averaged together and normalized to the Mmax value.

The soleus H-reflex and the M-wave amplitudes were measured as the peak-to-peak values in time windows determined for each subject. Typically, a time window of 30–45 ms poststimulus was used for the H-reflex and 6–23 ms poststimulus for the M-wave. To examine the phase-dependent modulation of the H-reflex, trials with a consistent M-wave size (reflecting a consistent level of stimulation) were selected for data analysis for comparing across different phases of step cycle (Capaday and Stein 1986; Edamura et al. 1991; Kido et al. 2004a; Makihara et al. 2012). That is, some of the responses with too large or too small M-waves were eliminated from further analyses. To measure the background EMG activity for H-reflex measurement during walking, the average soleus EMG activity was calculated for unstimulated steps and used as the control background EMG (Kido et al. 2004b; Makihara et al. 2012; Yang and Stein 1990). The H-reflex amplitude was plotted along the step cycle time, according to the time of the step cycle at which the reflex was elicited. As for the locomotor EMG activity, the H-reflexes at different times in the step cycle were sorted into 12 bins according to step cycle time and averaged for each bin (Kido et al. 2004b; Makihara et al. 2012; Zehr et al. 1997, 1998). Approximately 10 responses were averaged in each bin. To evaluate H-reflex modulation during locomotion the MI [i.e., 100 × (maximum H-reflex – minimum H-reflex)/maximum H-reflex] (Kido et al. 2004a; Makihara et al. 2012; Zehr and Kido 2001) was calculated over the step cycle.

As in the locomotor EMG, ankle, knee, and hip joint angles from individual steps were normalized to the mean step cycle time and averaged together to obtain the joint motion over the step cycle. Then, for each joint, the angle at foot contact, joint range of motion over the step cycle, peak flexion angle, peak extension angle, and median angle across the entire step cycle were calculated.

Data Analysis

As detailed in Thompson et al. 2018a, for each participant, whether MEP up-conditioning was successful or MEP control protocol affected MEP size, the average MEPs of the final six conditioning/control sessions were compared with the average MEPs of the six baseline sessions by unpaired Student’s t-test (one-tailed) with the α-level set at 0.05 (Thompson et al. 2009a, 2013, 2018a). In five of eight conditioning participants without SCI, the average MEP for conditioning sessions 19–24 was significantly larger than that for the six baseline sessions. The final MEP size [average of last three sessions (Thompson et al. 2009a)] for these five participants was 150 ± 13% (mean ± SE) of baseline value (Thompson et al. 2018a). In the other three conditioning participants, the MEP did not increase significantly. In all control participants without SCI, the average MEP for control sessions 19–24 did not differ from that for the six baseline sessions; the final MEP size for the control group was 96 ± 10% of baseline value. Since the final MEP size differed significantly between the conditioning group (n = 8) and the control group (n = 7) (P = 0.03 by unpaired Student’s t-test), we concluded that MEP increase was specific to up-conditioning.

In Results, we report the locomotor EMG, joint motion, and H-reflex results for the conditioning group of individuals without SCI in whom MEP up-conditioning was successful (n = 5), the control group of individuals without SCI (n = 7), and the conditioning group of individuals with SCI in whom MEP up-conditioning was successful and these measurements could be made (n = 7) (Thompson et al. 2018a). For 10-m walk test, the results from all 10 individuals with SCI are reported. To evaluate the effects of MEP conditioning, for each group’s parameters, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was applied to compare the values from before and after 24 conditioning/control sessions.

RESULTS

Locomotor EMG Activity, Soleus H-reflex Modulation, and Kinematics in the Conditioning and Control Groups of People Without SCI

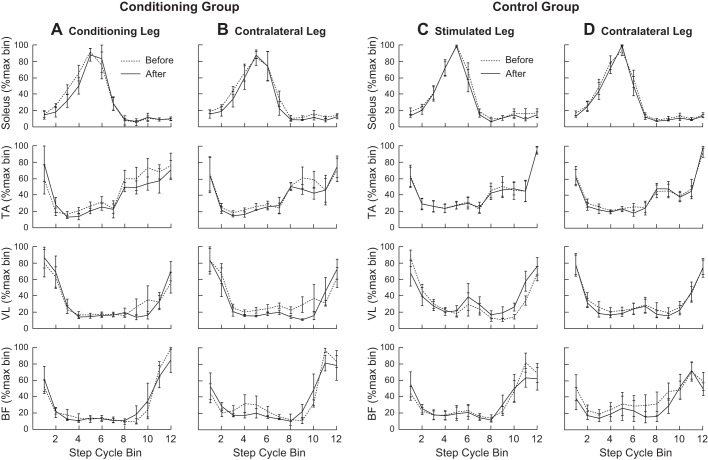

Before and after 24 conditioning/control sessions, locomotor EMG activity was recorded from the TA, soleus, (VL), and (BF) bilaterally, while the participant walked on the treadmill at a comfortable speed. For both the conditioning and control groups, the MI was high (>0.85) for each of the eight muscles before and did not differ significantly between the two locomotor EMG sessions (P > 0.05 in each muscle by paired Student’s t-test). Figure 2 shows the average normalized results from each of the eight muscles before and after 24 conditioning/control sessions. EMG modulation pattern across the step cycle did not change after MEP conditioning or control sessions in people without neurological conditions.

Fig. 2.

Average locomotor electromyography (EMG) activity in the conditioning (A and B, n = 5) and control (C and D, n = 7) groups of participants without known neurological conditions, from soleus, tibialis anterior (TA), vastus lateralis (VL), and biceps femoris (BF) of both legs before and after the 24 conditioning/control sessions. Conditioning group data include the data from individuals in whom MEP up-conditioning increased TA motor-evoked potential (MEP) size significantly. For each muscle, EMG amplitude in each of the 12 equal bins was normalized by the amplitude in the bin with the highest amplitude. There were no significant differences between the two measurements in any of the 12 bins in any of the eight muscles in either group.

Furthermore, to quantify the amount of swing-phase TA activity in the conditioned/stimulated leg, the TA EMG amplitudes for locomotor bins 8–12 were averaged together and normalized to the Mmax value. In the conditioning group, this TA activity was 7.3 ± 1.2% Mmax (mean ± SE) before and 8.0 ± 1.4% Mmax after, and did not change significantly (P = 0.18, by paired Student’s t -test). In the control group, it was 6.6 ± 1.4% Mmax before and 6.1 ± 1.8% Mmax after with no significant difference between them (P = 0.54). Thus, not only the EMG modulation, but also the conditioned (or stimulated) muscle’s EMG burst amplitude did not change after MEP conditioning or control sessions in these people.

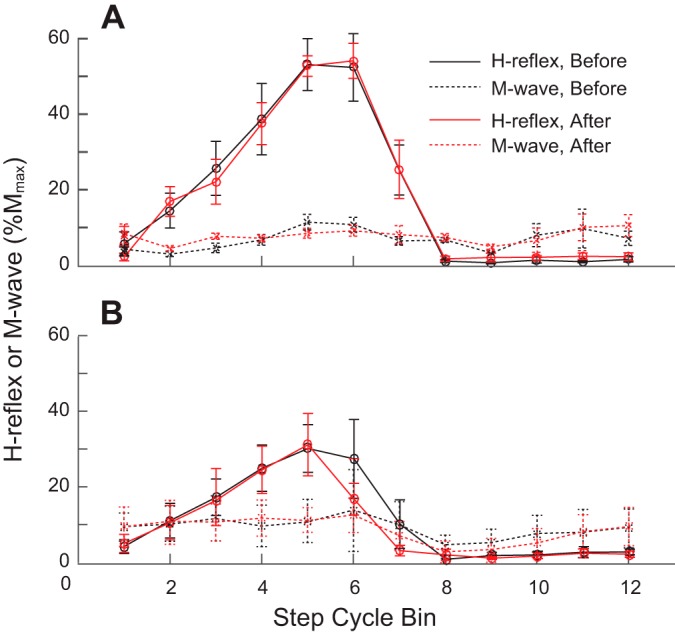

Soleus H-reflex was clearly modulated over the step cycle in both the conditioning and control groups, before and after conditioning/control sessions. The MI was very high in the conditioning group (0.99 ± 0.00 (mean ± SE) before and 0.99 ± 0.00 after) and in the control group (0.98 ± 0.00 before and 0.98 ± 0.00 after). As expected, the H-reflex was very low during swing, and reached its maximum value during stance. The H-reflex amplitude for each of the 12 bins of the step cycle did not differ between the two locomotor sessions (P = 0.14-0.98, by paired Student’s t-test) in both groups. The average locomotor H-reflex amplitude calculated by averaging values over 12 bins (Thompson et al. 2013) did not change after 24 conditioning sessions in the conditioning group (P = 0.98 by paired Student’s t-test) or after 24 control sessions in the control group (P = 0.23). Figure 3 displays locomotor H-reflex modulation over the step cycle (in %Mmax) before and after the 24 conditioning/control sessions. In both groups, the magnitude and pattern of modulation were comparable before and after.

Fig. 3.

Average soleus locomotor Hoffmann reflexes (H-reflexes) for the conditioning and control groups of participants without known neurological conditions. H-reflex sizes before and after the 30 conditioning sessions are expressed as %Mmax. As for locomotor electromyography (EMG) activity in Fig. 1, the step cycle was divided into 12 equal bins and an average reflex size for each bin was calculated. A: H-reflex and accompanying M-wave from five conditioning group participants in whom tibialis anterior (TA) motor-evoked potential (MEP) increased significantly. B: H-reflex and accompanying M-wave from seven control group participants. There were no significant differences between the measurements in any of the 12 bins in either group.

For each of the ankle, knee, and hip joints, the angle at foot contact, range of motion over the step cycle, peak flexion angle, peak extension angle, and median angle across the entire step cycle were calculated and compared between the two locomotor sessions. No significant differences were found in any of these joint motion measures in the conditioning group (P = 0.09-0.99, by paired Student’s t-test) and in the control group (P = 0.06–0.86). Thus, the conditioned or stimulated leg’s ankle joint motion did not change. Tables 2 and 3 summarize the joint motion parameters for all participants without known neurological injuries.

Table 2.

Summary of joint angles during walking in the conditioning group of participants without known neurological conditions in whom MEP up-conditioning increased TA MEP size significantly

| Joint ROM |

Peak Flexion Angle |

Peak Extension Angle |

Angle at FC |

Median Angle |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | after | before | after | before | after | before | after | before | after | |

| Conditioned leg | ||||||||||

| Ankle | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | −20 ± 2 | −18 ± 1 | −1 ± 2 | 0 ± 2 | −2 ± 1 | 0 ± 2 |

| Knee | 63 ± 1 | 63 ± 3 | 61 ± 2 | 60 ± 3 | −2 ± 2 | −2 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 11 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 |

| Hip | 46 ± 2 | 45 ± 3 | 30 ± 2 | 26 ± 3 | −16 ± 3 | −19 ± 2 | 29 ± 1 | 26 ± 3 | 12 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 |

| Contralateral leg | ||||||||||

| Ankle | 31 ± 3 | 34 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 | 12 ± 2 | −23 ± 3 | −21 ± 1 | −4 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 | −3 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 |

| Knee | 63 ± 4 | 62 ± 3 | 58 ± 5 | 61 ± 3 | −4 ± 2 | −1 ± 1 | −1 ± 3 | 2 ± 1 | 9 ± 3 | 12 ± 2 |

| Hip | 46 ± 2 | 45 ± 2 | 30 ± 3 | 28 ± 3 | −16 ± 4 | −16 ± 2 | 28 ± 2 | 27 ± 3 | 12 ± 3 | 10 ± 2 |

TA, tibialis anterior; MEP, motor-evoked potential, ROM, range of motion; FC, foot contact. All values are in degrees with the group mean ± SE. For the ankle joint, flexion = dorsiflexion and extension = plantarflexion.

Table 3.

Summary of joint angles during walking in the control group of participants without known neurological conditions

| Joint ROM |

Peak Flexion Angle |

Peak Extension Angle |

Angle at FC |

Median Angle |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | after | before | after | before | after | before | after | before | after | |

| Conditioned leg | ||||||||||

| Ankle | 40 ± 2 | 39 ± 3 | 17 ± 2 | 17 ± 2 | −24 ± 5 | −22 ± 2 | 0 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 |

| Knee | 61 ± 1 | 59 ± 1 | 59 ± 3 | 60 ± 1 | 0 ± 3 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 10 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 |

| Hip | 42 ± 2 | 40 ± 3 | 27 ± 1 | 31 ± 4 | −14 ± 2 | −10 ± 2 | 26 ± 1 | 29 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 | 15 ± 3 |

| Contralateral leg | ||||||||||

| Ankle | 43 ± 5 | 43 ± 4 | 17 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | −27 ± 4 | −26 ± 4 | −1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

| Knee | 62 ± 2 | 60 ± 2 | 62 ± 2 | 61 ± 2 | 0 ± 3 | 1 ± 3 | 2 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | 14 ± 2 |

| Hip | 39 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 | 27 ± 1 | 30 ± 3 | −12 ± 2 | −9 ± 2 | 26 ± 1 | 29 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | 16 ± 3 |

All values are in degrees with the group mean ± SE. For the ankle joint, flexion = dorsiflexion and extension = plantarflexion. TA, tibialis anterior; MEP, motor-evoked potential; ROM, range of motion; FC, foot contact.

Altogether, these results in locomotor EMG activity, soleus H-reflex modulation, and joint kinematics in these participants without injuries indicate that repeated application of single-pulse TMS or MEP up-conditioning does not disturb or alter normal locomotion.

10-m Walking Speed, Locomotor EMG Activity, and Joint Kinematics in People with SCI

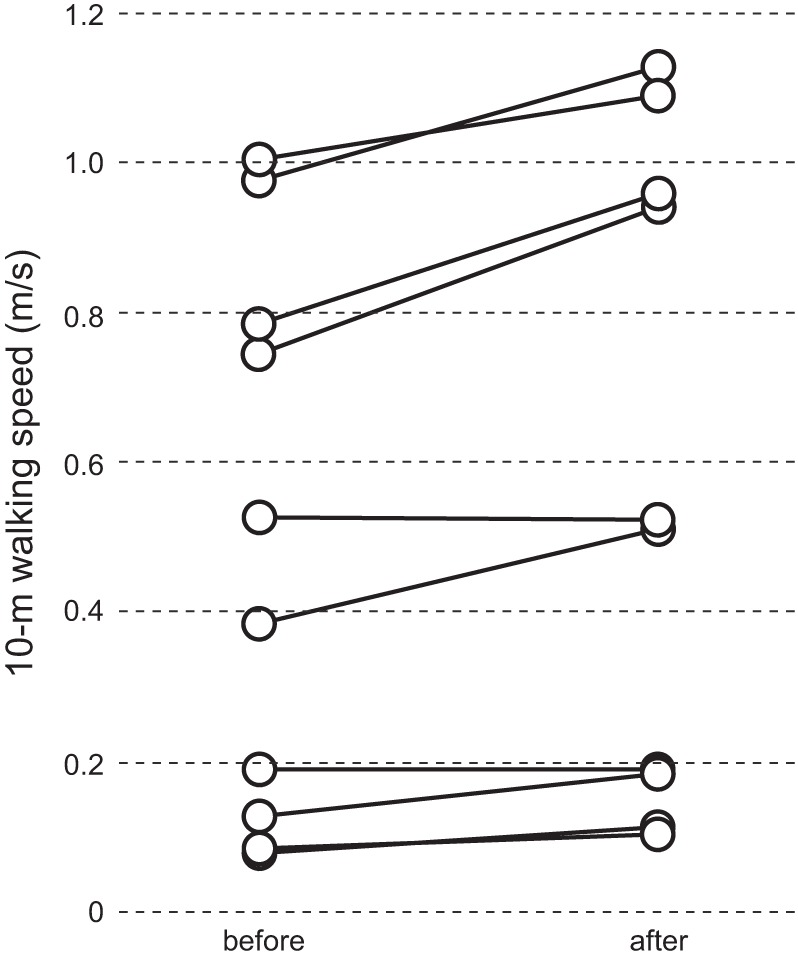

Figure 4 shows 10-m walking speeds for all 10 participants with SCI, measured before and after 24 up-conditioning sessions. TA MEP increased significantly in all but the participant with the lowest initial walking speed. The average walking speed for nine individuals, in whom TA MEP increased significantly, was 0.53 ± 0.12 m/s (mean ± SE) before, and significantly increased to 0.63 ± 0.14 m/s after conditioning (P = 0.007, paired Student’s t-test).

Fig. 4.

Ten-meter walking speed in individual participants with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI, n = 10). Tibialis anterior (TA) motor-evoked potential (MEP) increased significantly in all but the participant with the lowest initial walking speed.

Similar to the EMG measurements in people without SCI, before and after 24 conditioning/control sessions, locomotor EMG was recorded from the TA, soleus, VL, and BF, bilaterally, while the participant walked on the treadmill (n = 5) or overground (n = 2) at a comfortable speed. For both the conditioned and contralateral legs, locomotor EMG was modulated before and after; across participants and muscles, the MI ranged from 0.56 to 0.96 before and 0.59 to 0.96 after. While no significant changes were found in any single muscles (P > 0.09, by paired Student’s t-test), when MIs were pooled together from the four muscles of the conditioned leg, it improved significantly from 0.84 ± 0.02 (before) to 0.87 ± 0.01 (after) (P = 0.05, paired Student’s t-test). The pooled MI of the contralateral leg remained unchanged (i.e., 0.84 before and 0.84 after).

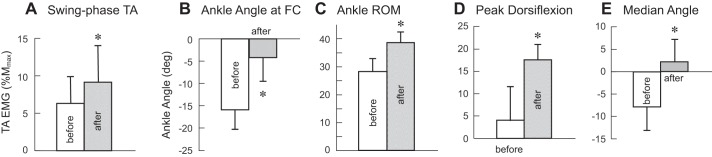

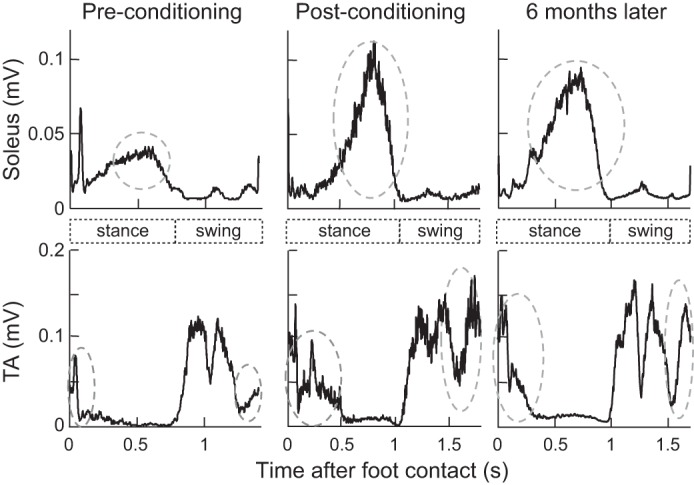

In the conditioned leg, the TA burst during the swing phase also increased in participants with SCI. TA EMG amplitudes for locomotor bins 8–12 significantly increased from 29 ± 11 µV (group mean ± SE) before to 39 ± 12 µV after (P = 0.004, paired Student’s t-test), which correspond to 6.3 ±3.6% Mmax (mean ± SE) before and 9.1 ± 5.0% Mmax after (P = 0.04, see Fig. 7A). Figure 5 shows soleus and TA locomotor EMG over the step cycle in a participant with SCI in whom TA MEP increased significantly. After successful MEP up-conditioning increased corticospinal excitation of the TA, the TA burst is clearly increased in the late swing-to-swing stance transition phases. The soleus burst in the mid-late stance phase for push-off appears to increase after conditioning. A similar clear increase in the soleus mid-late stance burst was also observed in three other individuals with SCI. The remaining three individuals with SCI in whom locomotor EMG was measured showed little change in the soleus burst amplitude (P = 0.1, by paired Student’s t-test). This individual came back to the laboratory 6 mo after conditioning ended, at which point, changes in locomotor EMG activity in the TA and soleus were still present.

Fig. 7.

Tibialis anterior (TA) activity and ankle joint motion before and after 24 conditioning sessions in the conditioned leg of the participants with spinal cord injury (SCI, n = 7). A: the amount of swing-phase TA activity, measured as the average value for locomotor bins 8–12. The amplitude is expressed in %Mmax. EMG, electromyography. B: ankle angle (deg., degree) at foot contact (FC). C: ankle range of motion (ROM) over the step cycle. D: ankle angle at the peak dorsiflexion, which typically occurred in the late stance phase. E: median ankle angle across the step cycle. Improved ankle dorsiflexion during locomotion is reflected in these changes. *Significant differences between before and after (P < 0.05, by paired Student’s t-test).

Fig. 5.

Rectified soleus and tibialis anterior (TA) locomotor electromyography (EMG) over the step cycle before and after motor-evoked potential (MEP) conditioning in a participant with spinal cord injury (SCI) in whom TA MEP increased significantly. Increased corticospinal excitation of the TA after conditioning is clearly visible in the late swing-to-swing stance transition phases. The soleus burst in the mid-late stance phase for push-off also appears to increase after conditioning. These improvements in locomotor EMG remain present 6 mo later.

In the participants with SCI, the contralateral TA activity (mean rectified TA EMG amplitude) in the swing phase also increased; the group mean (mean ± SE) amplitude was significantly larger after conditioning (57 ± 20 µV before and 67 ± 23 µV after, P = 0.01 by paired Student’s t-test). Since the Mmax was not measured in the contralateral TA, the amount of contralateral TA activity change cannot be expressed in %Mmax, unfortunately.

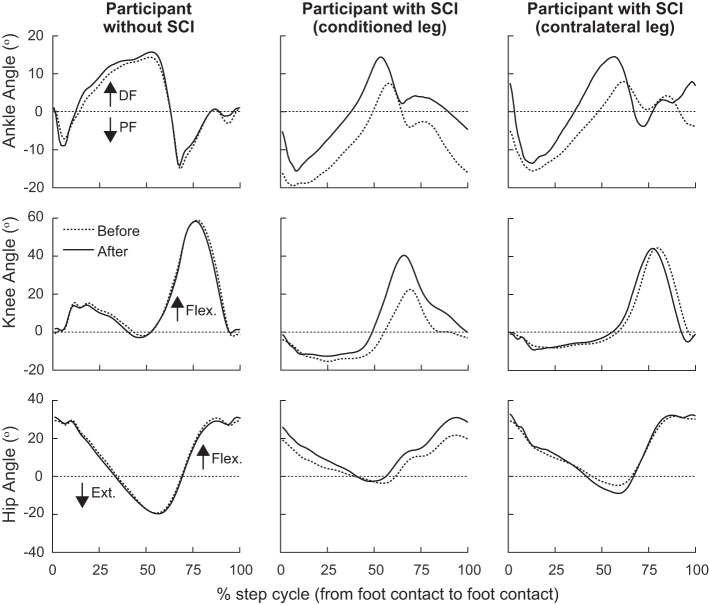

Different from the findings in participants without SCI, in participants with SCI, TA MEP up-conditioning appeared to affect joint motion, especially around the ankle joint. Figure 6 shows the ankle, knee, and hip joint motion over the step cycle before and after the 24 conditioning sessions in representative individuals in whom MEP conditioning successfully increased TA MEP size. In the conditioned leg of a participant with SCI after MEP conditioning, the ankle became less plantarflexed (or became dorsiflexed in some cases) at foot contact, the peak dorsiflexion angle increased, and the range of motion and the median ankle angle across the step cycle increased. The knee range of motion also increased, mostly from the increase of peak flexion angle. In the contralateral leg of the same participant with SCI, the ankle angle at foot contact and the peak dorsiflexion angle increased, while the joint motion of knee and hip, which was much less impaired to begin with, did not change. Figure 7, B–E shows changes in the ankle joint motion parameters as group values. Ankle angle at foot contact, the range of motion over the step cycle, the peak dorsiflexion angle, and the median ankle angle across the step cycle all increased (i.e., improved) significantly (P < 0.05, by paired Student’s t-test), indicating that ankle dorsiflexion during locomotion was increased after conditioning. Table 4 summarizes the joint motion parameters for participants with SCI.

Fig. 6.

Ankle, knee, and hip joint angles over the step cycle before and after the 24 conditioning sessions in representative individuals in whom motor-evoked potential (MEP) conditioning successfully increased tibialis anterior (TA) MEP size. In the conditioned leg of a participant without spinal cord injury (SCI, left), for any of the three joints, joint motion does not change after conditioning [ankle: + dorsiflexion (DF), − plantarflexion (PF); knee: + flexion (Flex.), − extension (Ext.); hip: + flexion, − extension]. In the conditioned leg of a participant with SCI (center), after MEP conditioning the ankle became more dorsiflexed at foot contact, the peak dorsiflexion angle increased, and the range of motion and the median ankle angle across the step cycle increased. In the contralateral leg of the same participant with SCI (right), the ankle angle at foot contact and the peak dorsiflexion angle increased.

Table 4.

Summary of joint angles during walking in participants with chronic incomplete SCI

| Joint ROM |

Peak Flexion Angle |

Peak Extension Angle |

Angle at FC |

Median Angle |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | after | before | after | before | after | before | after | before | after | |

| Conditioned leg | ||||||||||

| Ankle | 28 ± 6 | 38 ± 5* | 4 ± 7 | 18 ± 5* | −24 ± 3 | −20 ± 3 | −16 ± 5 | −4 ± 5* | −8 ± 6 | 2 ± 5* |

| Knee | 38 ± 6 | 49 ± 9* | 43 ± 6 | 50 ± 9 | 6 ± 8 | −2 ± 6 | 14 ± 6 | 11 ± 6 | 17 ± 7 | 11 ± 6 |

| Hip | 27 ± 5 | 36 ± 8* | 24 ± 4 | 25 ± 7 | −3 ± 4 | −11 ± 3 | 21 ± 4 | 21 ± 5 | 8 ± 3 | 7 ± 10 |

| Contralateral leg | ||||||||||

| Ankle | 34 ± 7 | 38 ± 6 | 7 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | −27 ± 9 | −27 ± 9 | −11 ± 8 | −2 ± 9* | −5 ± 3 | −1 ± 4* |

| Knee | 49 ± 10 | 54 ± 11 | 50 ± 3 | 56 ± 9 | 2 ± 10 | 2 ± 8 | 12 ± 7 | 14 ± 8 | 12 ± 8 | 14 ± 8 |

| Hip | 35 ± 4 | 34 ± 8 | 29 ± 3 | 31 ± 3 | −7 ± 2 | −3 ± 4 | 22 ± 4 | 25 ± 5 | 8 ± 4 | 12 ± 4* |

SCI, spinal cord injury; ROM, range of motion; FC, foot contact All values are in degree with the group mean ± SE. For the ankle joint, flexion = dorsiflexion and extension = plantarflexion.

Significant differences between before and after (P < 0.05, by paired Student’s t-test).

These results in 10-m walking speed, locomotor EMG, and joint kinematics in participants with SCI support the hypothesis that TA MEP up-conditioning administered during sitting can improve ankle joint motion (especially dorsiflexion) during locomotion in people with weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI.

DISCUSSION

This study set out to examine the effects of ankle dorsiflexor MEP operant conditioning on locomotion in people with normal gait and in people with weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI. Specifically, we hypothesized that in people with SCI, increasing the TA MEP through operant up-conditioning in sitting can improve dorsiflexion during locomotion, while in people without SCI or any other known neurological conditions, it would have little impact on already normal locomotion. The present results clearly support our hypothesis; MEP up-conditioning did not disturb normal locomotion, while it improved the TA activity and dorsiflexion during locomotion in people with incomplete SCI. Here, we discuss the functional implication of these findings.

Effects of TA MEP Up-Conditioning on Normal Locomotion in People Without SCI

In the present study, in participants without known neurological injuries, we found no systematic or consistent change across participants in locomotor EMG activity, soleus H-reflex modulation, and joint kinematics, indicating that repeated unilateral application of single-pulse TMS or MEP up-conditioning to the TA does not disturb normal locomotion. Despite a clear increase in TA MEP size with up-conditioning during sitting, the ankle joint motion during locomotion did not change in the conditioning group.

As discussed in Makihara et al. (Makihara et al. 2014), this lack of change in normal human locomotion after successful conditioning is different from what would be expected from previous studies in rats. In normal rats, soleus H-reflex conditioning alters locomotor EMG activity, H-reflexes, and kinematics (Chen et al. 2005, 2011), while the step-cycle symmetry and hip height (i.e., key features of locomotion) remain undisturbed by compensatory changes in EMG activity and kinematics (Chen et al. 2011). Why do the effects of conditioning differ between humans and rats? A plausible explanation may be found in anatomical and physiological interspecies differences (i.e., quadrupeds vs. bipeds) (Courtine et al. 2007; Nout et al. 2012). The inter-task transfer of induced plasticity and/or the location and extent of compensatory plasticity (Wolpaw 2010, 2018) may be dictated by mechanisms for maintaining effective locomotor function, which would likely differ between quadrupedal locomotion and bipedal locomotion. Beyond the interspecies differences, could there be any other explanations for why MEP conditioning would not be affecting normal locomotion? The present finding that TA activity and thus ankle dorsiflexion during locomotion were not affected by TA MEP up-conditioning may in part be explained by how the corticospinal pathways function during locomotion and how MEP conditioning induces corticospinal plasticity. As reported in Thompson et al. 2018a, MEP up-conditioning did not change the TA Mmax and Hmax, suggesting that the altered EMG recording condition or increased reflex excitability to Ia excitatory input was unlikely. It is more likely that the plasticity occurred at synaptic connections between the TA motoneurons and descending corticospinal tract neurons (Long et al. 2017; Urbin et al. 2017) and/or at the origin of corticospinal tract neurons (i.e., motor-related areas of the cortex), both of which could directly impact the extent of corticospinal excitation of motoneurons. It is conceivable that in people without injuries, because an appropriate amount of locomotor TA activity had always been achieved, there was no need to use the additional corticospinal excitatory drive gained through conditioning to produce the normal, same speed of locomotion. That leaves a possibility that the impact might have been detected differently, if the TA activity was measured during different directions [e.g., backward walking (Schneider and Capaday 2003)] or speeds [e.g., (Hundza and Zehr 2009; Kido et al. 2004b)] of locomotion. Similarly, to reflex conditioning, MEP conditioning could also induce changes in the properties of multiple corticospinal and spinal neurons, including motoneurons and interneurons (Carp et al. 2001a, 2001b; Carp and Wolpaw 1994, 1995; Halter et al. 1995; Pillai et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2009, 2012), with a sum of those changes not affecting locomotion (Wolpaw 2010, 2018). Occurrence and mechanisms of such multisite plasticity would need to be investigated in the future.

Effects of TA MEP Up-Conditioning on Impaired Locomotion in People SCI

In the present group of individuals with SCI, in whom TA MEP increased significantly (n = 9), walking speed increased by 0.1 m/s (corresponding to 21 ± 6% increase). This meets the smallest real difference of 0.05–0.10 m/s and minimally clinically important difference of 0.10–0.15 m/s, previously reported for similar populations of individuals with SCI (Forrest et al. 2014; Lam et al. 2008; Musselman and Yang 2014; Yang et al. 2014). Moreover, in clear contrast to the lack of change in locomotion in people without injuries, in participants with weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI, the conditioned leg’s dorsiflexion increased, consistently. These results suggest that TA MEP up-conditioning may be able to alleviate foot drop in people with SCI. Changes in ankle joint motion observed in the present group of participants with SCI after conditioning is most likely a result of increased TA activity during the swing-to-swing stance transition phases (see Figs. 5 and 7A). In these participants, the conditioned TA’s swing-phase activity increased by 70% on average (with a range of 6–221% increase), supporting this view. During the swing phase of the step cycle, corticospinal excitability for the TA is high in people without injuries (Capaday et al. 1999; Schubert et al. 1997), probably reflecting the significant contribution of corticospinal drive to TA activation.

In addition to the improvements in the conditioned leg’s ankle joint motion, the contralateral leg’s ankle joint motion also improved, as summarized in Table 4 and shown in Fig. 6. These improvements may be explained by the increased swing-phase TA activity in the contralateral leg. In the present participants with SCI, the contralateral TA’s swing-phase activity increased by 36% on average (range 1–141% increase). Although, the quantification of contralateral TA activity in %Mmax is not available with the present data set, it is unlikely that the contralateral leg’s increase in dorsiflexion at foot contact and increase in swing-phase TA activity in every individual in whom we could obtain these measurements is merely coincidental. It is also unlikely that these increases reflect measurement errors, as we were able to achieve stable recording of surface EMG over many experimental sessions during many months with careful mapping and recording of electrode locations for the conditioned leg in this study (see Stability of Background EMG, TA M-Wave, and TA H-Reflex) and also in our previous studies (Makihara et al. 2014; Thompson et al. 2009a, 2013, 2018b). Thus, the present observation of increased swing-phase activity in the contralateral TA could be factual. Clearly, this potentially important finding needs to be confirmed through future studies.

As to why the contralateral TA activity could be improved, several potential reasons are worth mentioning. The first possibility is that MEP up-conditioning improved both the contralateral and ipsilateral corticospinal connections. It could be that, while the MEP conditioning protocol was intended to target the corticospinal connection to the TA contralateral to the side to which the TMS was applied, the ipsilateral TA was also stimulated through the ipsilateral connection, and thereby improved its function along with the contralateral connection. The second potential explanation is related to the nature of TMS procedure in the lower extremity. Since the optimum cortical TMS location for eliciting MEP in the TA is very close to the midline, it is quite possible that TMS would stimulate the TA motor areas on both hemispheres. In this situation, effects of MEP conditioning may be produced bilaterally. These possibilities deserve a thorough examination through systematic monitoring of the contralateral TA EMG and MEP in the future investigations. The third is the “cross-education” effect of training one limb leading to the improvement in strength or task performance of the contralateral (untrained) limb (Christiansen et al. 2017; Green and Gabriel 2018; Lee et al. 2010; Perez et al. 2007a, 2007b; Ruddy and Carson 2013; Ruddy et al. 2017). In people without neurological injuries and people after stroke, Dragert and Zehr (Dragert and Zehr 2011, 2013) found that the unilateral dorsiflexion strengthening training can improve the dorsiflexion strength bilaterally. Thus, one might suspect that TA MEP conditioning in one leg may have produced a similar cross-education effect on the other leg. However, the fact that the trained skill through MEP conditioning is a skill to increase MEP size on one leg and not a skill or task of increasing dorsiflexion during locomotion, or another fact that TA MVC in the conditioned leg did not increase significantly over the course of MEP conditioning (Thompson et al. 2018a), makes cross-education a less likely mechanism of observed effects in the contralateral TA activity during locomotion. The fourth potential explanation is that increasing the corticospinal excitability for the conditioned leg’s TA would induce the spinal cord multisite plasticity, which improved activation of the contralateral TA, as well as many other leg muscles (see Fig. 5 for example of change in the locomotor soleus EMG activity). Indeed, in the present group of participants with SCI, modulation of locomotor EMG was improved in multiple leg muscles, supporting this possibility. Considering that similarly extensive improvements of locomotor EMG modulation have also been found in the previous soleus H-reflex conditioning study in people with incomplete SCI (Thompson et al. 2013), it is probable that regardless of whether the pathway targeted is a reflex pathway or a corticospinal pathway, operant conditioning-induced guided plasticity in the targeted pathway would end up inducing CNS multisite plasticity (Thompson and Wolpaw 2015). This would be a necessary process in accommodating the conditioning-induced (i.e., targeted) change in the network of spinal pathways through a process of negotiation (Wolpaw 2010, 2018): a negotiation among motor skills and behaviors to settle the properties of the common spinal neurons and synapses that that they all use. This theory has been thoroughly discussed in (Wolpaw 2018) as the negotiated equilibrium model of spinal cord function.

To fully understand the mechanisms for the observed bilateral impact of unilateral MEP conditioning, further investigations that include systematic examination and monitoring of contralateral EMG and MEP are clearly needed. Additionally, MEP conditioning in the upper extremity may help to dissociate TMS methodological causes from physiological causes in producing bilateral effects.

Functional Implications

The present study indicates that MEP conditioning does not alter normal locomotion. In participants without known neurological injuries, MEP up-conditioning to the TA that produces a clear increase in the TA MEP does not change ankle joint motion and does not disturb normal locomotion. In contrast, in individuals with weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI, ankle dorsiflexion increased and locomotion improved after MEP conditioning. Such differing functional effects of MEP conditioning between people with SCI and without injuries are consistent with findings from previous H-reflex conditioning studies (Chen et al. 2005, 2006, 2011, 2014a, 2014b; Makihara et al. 2014; Thompson et al. 2013). In people, functional changes occurred when conditioning induced beneficial plasticity and improved impaired locomotion, whereas when conditioning induced nonbeneficial plasticity, there was little impact on locomotor EMG and joint motion, and thereby locomotor function (Makihara et al. 2014; Thompson et al. 2013). In rats with SCI, when conditioning induced beneficial plasticity and improved locomotor EMG and joint kinematics, such improvements in locomotion stayed, whereas when conditioning induced nonbeneficial plasticity, there was little impact on locomotor function in net sum (Chen et al. 2005, 2006, 2011, 2014a, 2014b). Together with those previous studies, the present study suggests a potential of operant conditioning approach as a useful therapeutic tool for enhancing motor function recovery in people with SCI (Thompson and Wolpaw 2015) and other CNS disorders, such as multiple sclerosis (Thompson et al. 2018b) and stroke. To date, we have not observed unwanted functional effects of conditioning, which helps us to propose that this approach is a safe therapeutic option. To determine the efficacy of this new approach, more clinical studies will need to follow. Additionally, to refine the conditioning protocol and design better implementation strategies to be used in the clinics in the future, further investigations are needed to identify the mechanisms of conditioning-aided functional improvements.

Methodological Limitations and Considerations

Several methodological limitations in the present study would warrant brief discussion. First, this study does not include a control group of participants with SCI, which limits evaluation of functional impact of MEP up-conditioning. Since the study was conducted along the initial investigation of MEP operant conditioning to examine its feasibility, the SCI control group was not available. Thus, the present preliminary findings need to be confirmed through future clinical studies that include an appropriate control group of participants with SCI. Second, as mentioned in Results, the present data set does not include the measurement of contralateral TA Mmax with CPn stimulation. Normalization of EMG activity by the Mmax value would have verified an important finding that a unilateral application of TA MEP conditioning could improve the activation of contralateral TA. Contralateral TA Mmax is another important measurement to be included in future study. Third, the present study included only a 10-m walk test as a functional measure. As we observed MEP up-conditioning may improve ankle joint motion during locomotion in this study, it would be appropriate now to further examine potential functional impact of this approach. Together with the inclusion of a control group with SCI, functional assessments, such as a six-minute walk test, Berg Balance test, joint range of motion, and manual muscle strength test, are to be included in the future studies to develop a comprehensive picture of functional impact of MEP conditioning.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of operantly up-conditioning the ankle dorsiflexor MEP on locomotion in people with normal gait and in people with weak dorsiflexion due to chronic incomplete SCI. We found that in people without SCI or any other known neurological conditions, increasing the TA MEP through up-conditioning did not disturb or significantly change normal locomotion. In contrast, in people with SCI, MEP up-conditioning increased the swing-phase TA activity and improved ankle joint motion during locomotion. Together with the findings from previous reflex conditioning studies, the present study supports the possibility that operant conditioning protocols may be used as therapeutic tools for enhancing motor function recovery in people with SCI and other CNS disorders (Thompson et al. 2018b; Thompson and Wolpaw 2015), and encourages future clinical and basic science studies to further our understanding on inducing the targeted plasticity for guiding beneficial CNS multisite plasticity.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by the Morton Cure Paralysis Foundation, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS069551 to A. K. Thompson, the New York State Spinal Cord Injury Trust Fund Grant C023685 and C029131to A. K. Thompson, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM104941, and the Institutional Development Award to Binder-MacLeod.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.K.T. and J.S. conceived and designed research; A.K.T., G.F., L.S., B.F., J.B., and J.S. performed experiments; A.K.T., G.F., L.S., and B.F. analyzed data; A.K.T., J.B., and J.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.K.T. prepared figures; A.K.T. drafted manuscript; A.K.T., G.F., L.S., J.B., and J.S. edited and revised manuscript; A.K.T., G.F., L.S., B.F., J.B., and J.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Wayne Feng and late Dr. Ferne Pomerantz for neurological screening of study participants, Rachel Cote, Dr. Erhieyovbe Emore, Stephanie Pudlik, Ms. Bridgette Pouliot, and Eric Monsch for assistance in data collection and analyses, and Christina Gill for study coordination.

REFERENCES

- Barthélemy D, Willerslev-Olsen M, Lundell H, Conway BA, Knudsen H, Biering-Sørensen F, Nielsen JB. Impaired transmission in the corticospinal tract and gait disability in spinal cord injured persons. J Neurophysiol 104: 1167–1176, 2010. doi: 10.1152/jn.00382.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer B, Hopkins-Rosseel DH. Motor cortical mapping of proximal upper extremity muscles following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 35: 205–212, 1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calancie B, Alexeeva N, Broton JG, Suys S, Hall A, Klose KJ. Distribution and latency of muscle responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation of motor cortex after spinal cord injury in humans. J Neurotrauma 16: 49–67, 1999. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Lavoie BA, Barbeau H, Schneider C, Bonnard M. Studies on the corticospinal control of human walking. I. Responses to focal transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. J Neurophysiol 81: 129–139, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Stein RB. Amplitude modulation of the soleus H-reflex in the human during walking and standing. J Neurosci 6: 1308–1313, 1986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-05-01308.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp JS, Chen XY, Sheikh H, Wolpaw JR. Motor unit properties after operant conditioning of rat H-reflex. Exp Brain Res 140: 382–386, 2001a. doi: 10.1007/s002210100830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp JS, Chen XY, Sheikh H, Wolpaw JR. Operant conditioning of rat H-reflex affects motoneuron axonal conduction velocity. Exp Brain Res 136: 269–273, 2001b. doi: 10.1007/s002210000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp JS, Wolpaw JR. Motoneuron plasticity underlying operantly conditioned decrease in primate H-reflex. J Neurophysiol 72: 431–442, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp JS, Wolpaw JR. Motoneuron properties after operantly conditioned increase in primate H-reflex. J Neurophysiol 73: 1365–1373, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XY, Wolpaw JR. Operant conditioning of H-reflex in freely moving rats. J Neurophysiol 73: 411–415, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen L, Liu R, Wang Y, Chen XY, Wolpaw JR. Locomotor impact of beneficial or nonbeneficial H-reflex conditioning after spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 111: 1249–1258, 2014a. doi: 10.1152/jn.00756.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen L, Wang Y, Wolpaw JR, Chen XY. Operant conditioning of rat soleus H-reflex oppositely affects another H-reflex and changes locomotor kinematics. J Neurosci 31: 11370–11375, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1526-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen L, Wang Y, Wolpaw JR, Chen XY. Persistent beneficial impact of H-reflex conditioning in spinal cord-injured rats. J Neurophysiol 112: 2374–2381, 2014b. doi: 10.1152/jn.00422.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen XY, Jakeman LB, Chen L, Stokes BT, Wolpaw JR. Operant conditioning of H-reflex can correct a locomotor abnormality after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurosci 26: 12537–12543, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2198-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen XY, Jakeman LB, Schalk G, Stokes BT, Wolpaw JR. The interaction of a new motor skill and an old one: H-reflex conditioning and locomotion in rats. J Neurosci 25: 6898–6906, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1684-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen L, Larsen MN, Grey MJ, Nielsen JB, Lundbye-Jensen J. Long-term progressive motor skill training enhances corticospinal excitability for the ipsilateral hemisphere and motor performance of the untrained hand. Eur J Neurosci 45: 1490–1500, 2017. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Bunge MB, Fawcett JW, Grossman RG, Kaas JH, Lemon R, Maier I, Martin J, Nudo RJ, Ramon-Cueto A, Rouiller EM, Schnell L, Wannier T, Schwab ME, Edgerton VR. Can experiments in nonhuman primates expedite the translation of treatments for spinal cord injury in humans? Nat Med 13: 561–566, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nm1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey NJ, Smith HC, Savic G, Maskill DW, Ellaway PH, Frankel HL. Comparison of input-output patterns in the corticospinal system of normal subjects and incomplete spinal cord injured patients. Exp Brain Res 127: 382–390, 1999. doi: 10.1007/s002210050806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragert K, Zehr EP. Bilateral neuromuscular plasticity from unilateral training of the ankle dorsiflexors. Exp Brain Res 208: 217–227, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragert K, Zehr EP. High-intensity unilateral dorsiflexor resistance training results in bilateral neuromuscular plasticity after stroke. Exp Brain Res 225: 93–104, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edamura M, Yang JF, Stein RB. Factors that determine the magnitude and time course of human H-reflexes in locomotion. J Neurosci 11: 420–427, 1991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00420.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier C, Imbeault MA, Ung V, Capaday C. On the soleus H-reflex modulation pattern during walking. Exp Brain Res 151: 420–425, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everaert DG, Thompson AK, Chong SL, Stein RB. Does functional electrical stimulation for foot drop strengthen corticospinal connections? Neurorehabil Neural Repair 24: 168–177, 2010. doi: 10.1177/1545968309349939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest GF, Hutchinson K, Lorenz DJ, Buehner JJ, Vanhiel LR, Sisto SA, Basso DM. Are the 10 meter and 6 minute walk tests redundant in patients with spinal cord injury? PLoS One 9: e94108, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LA, Gabriel DA. The cross education of strength and skill following unilateral strength training in the upper and lower limbs. J Neurophysiol 120: 468–479, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00116.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter JA, Carp JS, Wolpaw JR. Operantly conditioned motoneuron plasticity: possible role of sodium channels. J Neurophysiol 73: 867–871, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundza SR, Zehr EP. Suppression of soleus H-reflex amplitude is graded with frequency of rhythmic arm cycling. Exp Brain Res 193: 297–306, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido A, Tanaka N, Stein RB. Spinal excitation and inhibition decrease as humans age. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 82: 238–248, 2004a. doi: 10.1139/y04-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido A, Tanaka N, Stein RB. Spinal reciprocal inhibition in human locomotion. J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 1969–1977, 2004b. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01060.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerquist O, Zehr EP, Baldwin ER, Klakowicz PM, Collins DF. Diurnal changes in the amplitude of the Hoffmann reflex in the human soleus but not in the flexor carpi radialis muscle. Exp Brain Res 170: 1–6, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T, Noonan VK, Eng JJ, SCIRE Research Team . A systematic review of functional ambulation outcome measures in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 46: 246–254, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Hinder MR, Gandevia SC, Carroll TJ. The ipsilateral motor cortex contributes to cross-limb transfer of performance gains after ballistic motor practice. J Physiol 588: 201–212, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepert J, Bauder H, Wolfgang HR, Miltner WH, Taub E, Weiller C. Treatment-induced cortical reorganization after stroke in humans. Stroke 31: 1210–1216, 2000a. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepert J, Graef S, Uhde I, Leidner O, Weiller C. Training-induced changes of motor cortex representations in stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand 101: 321–326, 2000b. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.90337a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepert J, Miltner WH, Bauder H, Sommer M, Dettmers C, Taub E, Weiller C. Motor cortex plasticity during constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke patients. Neurosci Lett 250: 5–8, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J, Federico P, Perez MA. A novel cortical target to enhance hand motor output in humans with spinal cord injury. Brain 140: 1619–1632, 2017. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makihara Y, Segal RL, Wolpaw JR, Thompson AK. H-reflex modulation in the human medial and lateral gastrocnemii during standing and walking. Muscle Nerve 45: 116–125, 2012. doi: 10.1002/mus.22265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makihara Y, Segal RL, Wolpaw JR, Thompson AK. Operant conditioning of the soleus H-reflex does not induce long-term changes in the gastrocnemius H-reflexes and does not disturb normal locomotion in humans. J Neurophysiol 112: 1439–1446, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00225.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manella KJ, Roach KE, Field-Fote EC. Operant conditioning to increase ankle control or decrease reflex excitability improves reflex modulation and walking function in chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 109: 2666–2679, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.01039.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay WB, Lee DC, Lim HK, Holmes SA, Sherwood AM. Neurophysiological examination of the corticospinal system and voluntary motor control in motor-incomplete human spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res 163: 379–387, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman KE, Yang JF. Spinal Cord Injury Functional Ambulation Profile: a preliminary look at responsiveness. Phys Ther 94: 240–250, 2014. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nout YS, Rosenzweig ES, Brock JH, Strand SC, Moseanko R, Hawbecker S, Zdunowski S, Nielson JL, Roy RR, Courtine G, Ferguson AR, Edgerton VR, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, Tuszynski MH. Animal models of neurologic disorders: a nonhuman primate model of spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics 9: 380–392, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Tanaka S, Wise SP, Sadato N, Tanabe HC, Willingham DT, Cohen LG. Neural substrates of intermanual transfer of a newly acquired motor skill. Curr Biol 17: 1896–1902, 2007a. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Wise SP, Willingham DT, Cohen LG. Neurophysiological mechanisms involved in transfer of procedural knowledge. J Neurosci 27: 1045–1053, 2007b. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4128-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TH, Kliim-Due M, Farmer SF, Nielsen JB. Childhood development of common drive to a human leg muscle during ankle dorsiflexion and gait. J Physiol 588: 4387–4400, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TH, Willerslev-Olsen M, Conway BA, Nielsen JB. The motor cortex drives the muscles during walking in human subjects. J Physiol 590: 2443–2452, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.227397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S, Wang Y, Wolpaw JR, Chen XY. Effects of H-reflex up-conditioning on GABAergic terminals on rat soleus motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci 28: 668–674, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06370.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy KL, Carson RG. Neural pathways mediating cross education of motor function. Front Hum Neurosci 7: 397, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy KL, Leemans A, Woolley DG, Wenderoth N, Carson RG. Structural and functional cortical connectivity mediating cross education of motor function. J Neurosci 37: 2555–2564, 2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2536-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Capaday C. Progressive adaptation of the soleus H-reflex with daily training at walking backward. J Neurophysiol 89: 648–656, 2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.00403.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]