Abstract

Precise motion control is critical to human survival on Earth and in space. Motion sensation is inherently imprecise, and the functional implications of this imprecision are not well understood. We studied a “vestibular” manual control task in which subjects attempted to keep themselves upright with a rotational hand controller (i.e., joystick) to null out pseudorandom, roll-tilt motion disturbances of their chair in the dark. Our first objective was to study the relationship between intersubject differences in manual control performance and sensory precision, determined by measuring vestibular perceptual thresholds. Our second objective was to examine the influence of altered gravity on manual control performance. Subjects performed the manual control task while supine during short-radius centrifugation, with roll tilts occurring relative to centripetal accelerations of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.33 GC (1 GC = 9.81 m/s2). Roll-tilt vestibular precision was quantified with roll-tilt vestibular direction-recognition perceptual thresholds, the minimum movement that one can reliably distinguish as leftward vs. rightward. A significant intersubject correlation was found between manual control performance (defined as the standard deviation of chair tilt) and thresholds, consistent with sensory imprecision negatively affecting functional precision. Furthermore, compared with 1.0 GC manual control was more precise in 1.33 GC (−18.3%, P = 0.005) and less precise in 0.5 GC (+39.6%, P < 0.001). The decrement in manual control performance observed in 0.5 GC and in subjects with high thresholds suggests potential risk factors for piloting and locomotion, both on Earth and during human exploration missions to the moon (0.16 G) and Mars (0.38 G).

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The functional implications of imprecise motion sensation are not well understood. We found a significant correlation between subjects’ vestibular perceptual thresholds and performance in a manual control task (using a joystick to keep their chair upright), consistent with sensory imprecision negatively affecting functional precision. Furthermore, using an altered-gravity centrifuge configuration, we found that manual control precision was improved in “hypergravity” and degraded in “hypogravity.” These results have potential relevance for postural control, aviation, and spaceflight.

Keywords: human, manual control, otoliths, psychophysics, semicircular canals, thresholds, vestibular perceptual threshold

INTRODUCTION

Precise and accurate motion control is important for survival, such as in older individuals climbing stairs in the dark or pilots landing an aircraft or spacecraft. Sensorimotor responses and perception are inherently imprecise because of noise in neural systems (Faisal et al. 2008). Imprecision includes trial-by-trial and temporal variations in sensations, as opposed to overall systematic errors such as bias. In this study, we aimed to focus on imprecision arising in the vestibular system. The vestibular system includes the semicircular canals, which sense angular rotation, and the otolith organs, which sense the combination of inertial acceleration and gravity. Although other sources of sensory information play a role in motion sensation in the dark (Mittelstaedt 1996; Valko et al. 2012), the predominant role of the vestibular organs has been demonstrated for whole body motion perception with the head held so that the neck is straight (Valko et al. 2012). Thus we use the term “vestibular,” while recognizing that our self-motion perception and control tasks involve other sensory contributors to some degree.

A number of studies have measured the precision of vestibular responses at varying levels (i.e., neuronal, perceptual, motor). The precision of afferent signals has been characterized by measuring variability in firing rate in squirrel monkeys (Fernandez and Goldberg 1971) and macaque monkeys (Jamali et al. 2009; Sadeghi et al. 2007). Perceptual precision has been characterized by measuring intertrial variability in subjective visual vertical tasks in humans (De Vrijer et al. 2009; Tarnutzer et al. 2009). On the other hand, vestibular perceptual thresholds in humans (Benson et al. 1986, 1989; Grabherr et al. 2008; Valko et al. 2012) have been determined by repeatedly exposing subjects to small motions to the left or right in the dark and asking them to report their perceived motion direction. Using signal detection theory, we can relate the thresholds determined in these studies to the imprecision or noise associated with the underlying sensory signal (Green and Swets 1966; Merfeld 2011). Motor variability in reflexive eye movements (vestibuloocular reflex; VOR) evoked by yaw rotation in rhesus monkeys (Haburcakova et al. 2012) and humans (Nouri and Karmali 2018; Seemungal et al. 2004) is similar to human perceptual yaw rotation thresholds, suggesting a common, sensory source of noise. Finally, the potential impact of vestibular imprecision on VOR and perceptual dynamics has been examined with computational models (Borah et al. 1988; Karmali et al. 2018; Karmali and Merfeld 2012; Laurens and Angelaki 2017; Laurens and Droulez 2007; MacNeilage et al. 2008; Paulin et al. 1989).

Vestibular perceptual thresholds vary dramatically across individuals, even among normal, healthy individuals who could pass a modified Romberg balance test (Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016). It is unclear what functional implications may arise from this intersubject variability in sensory precision. To more directly address this question, we studied whether vestibular precision, measured with vestibular perceptual thresholds, underlies performance in a functional task. Specifically, we determined whether roll-tilt vestibular perceptual thresholds predict performance in a manual control task (Clark et al. 2015a; Merfeld 1996; Panic et al. 2015; Riccio et al. 1992; Vimal et al. 2016). We hypothesized that manual control performance would be correlated with thresholds across subjects. The potential relevance and application of these results to our understanding of postural control and piloting are detailed in discussion.

Furthermore, we examined whether manual control performance would change in an altered gravity environment. Previous studies have done so in a hypergravity environment (i.e., >1 G) with a long-arm centrifuge (Clark et al. 2015a) and in astronauts after returning from microgravity (Merfeld 1996). Since no study has examined the effects of hypogravity (i.e., between 0 and 1 G) on manual control, we studied manual control in hypergravity and hypogravity analogs, in which subjects perform the manual control task relative to centripetal acceleration during short-arm centrifugation (details in methods). There is evidence that orientation perception depends on the “shear component” of the forces acting on the otolith organ (Bortolami et al. 2006; Clark et al. 2015c; Schoene 1964; Young 1982), although with a nonlinear relationship (Bortolami et al. 2006). Thus we hypothesized that the sensory information available to the subject to perform the manual control task would be more salient in the hypergravity analog, resulting in more precise manual control, and less salient in the hypogravity analog, resulting in less precise manual control. The potential application of these results to piloting and locomotion in hypogravity environments like on the moon and Mars is detailed in discussion.

METHODS

Overview.

Eleven subjects were studied by measuring their thresholds and manual control performance. For the remainder of this report, we use the term “threshold” to refer to roll-tilt vestibular perceptual direction-recognition thresholds unless otherwise stated. Thresholds were assayed in roll tilt with subjects upright relative to gravity and no centrifugation. Manual control was studied during centrifugation in the presence of different centripetal accelerations (GC, where 1 GC = 9.81 m/s2), in two different subexperiments (Table 1). Seven subjects (n = 7, 26.6 ± 6.3 yr) participated in subexperiment 1, which consisted of a manual control task performed with 1.0 GC and 1.33 GC centripetal acceleration. Ten subjects (n = 10, 27.9 ± 6.0 yr) participated in subexperiment 2, which consisted of the same manual control task with 1.0 GC and 0.5 GC centripetal acceleration. Six subjects overlapped between the two groups, yielding a total of 11 subjects. In the threshold task, subjects were asked to report their perception of small tilts to either the left or right, and thresholds were computed by fitting a cumulative Gaussian psychometric curve to binary responses. In the manual control task, subjects were asked to use a joystick to keep their chair aligned in roll tilt with their perception of down while the chair tilt was randomly perturbed. Performance was determined by calculating the variability of the chair position.

Table 1.

Manual control testing order for the two subexperiments

| Conditions and Subjects | Experimental Protocol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subexperiment 1 | ||||

| 1.0 GC and 1.33 GC; 7 subjects | 1.0 GC practice (218°/s) | 1.0 GC test (218°/s) | 1.33 GC practice (254°/s) | 1.33 GC test (254°/s) |

| 3 trials | 3 trials | 3 trials | 3 trials | |

| Subexperiment 2 | ||||

| 1.0 GC and 0.5 GC; 10 subjects (6 overlapping subjects, who performed this subexperiment second) | 1.0 GC practice (218°/s) | 1.0 GC test (218°/s) | 0.5 GC practice (154°/s) | 0.5 GC test (154°/s) |

| 9 trials | 3 trials | 3 trials | 3 trials | |

GC, centripetal acceleration.

Subjects.

All subjects performed the experiment after giving written informed consent, and all experiments were approved by the local human studies committees at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Subjects completed a three-tier screening process before recruitment. The first tier was a secure web-based subject health screening questionnaire on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Harris 2012). On the basis of this questionnaire we included subjects aged 18–45 yr who were able to fit comfortably in the motion devices and were in good health. Exclusion criteria included cardiovascular disease, severe diabetes, respiratory conditions (including asthma and emphysema), neurologic disorders, prostatic hypertrophy, gastrointestinal disorders, treatment for cancer, severe neck and spinal injuries, and pregnant women. Second, a Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary physician reviewed subjects’ medical history during an office visit and determined fitness to undergo centrifugation. No subjects were screened out during either of these two phases. Finally, subjects underwent a clinical vestibular screening that consisted of angular VOR measurement during sinusoidal vertical-axis rotation in the dark, electronystagmogram without calorics, and visual-vestibular interaction testing in which subjects viewed a chair-fixed target during vertical-axis rotation. Clinical vestibular screening exclusion factors included evidence of asymmetric VOR responses during rotational testing and age-adjusted VOR time constant < 12.6 s. Here, three subjects were excluded after a clinician (not associated with the study) determined that they had signs of abnormal vestibular function, specifically 1) an abnormal rightward VOR bias; 2) a reduced VOR gain and shortened time constant; and 3) a borderline reduction in VOR time constant. Subjects that met the inclusion criteria participated in one or both of the subexperiments, based on their availability.

Artificial gravity environment.

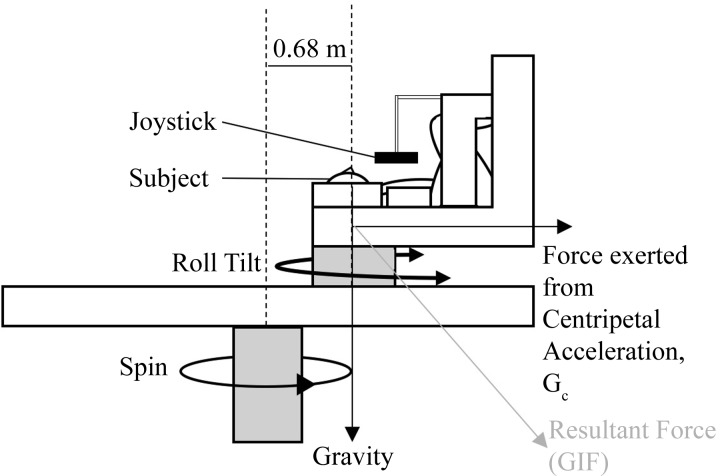

The experiments used the Eccentric Rotator (Neuro Kinetics, Pittsburgh, PA), a multiactuator motion device. The subject was supine in the Earth horizontal plane on a chair mounted on the device. The primary centrifuge spin axis rotated clockwise (as seen from above) about an Earth-vertical axis at a constant velocity to create a centripetal acceleration. Subjects were positioned with the ear 0.68 m from the centrifuge spin axis with feet pointing outward. Spin rate was determined for each of the GC levels at the head (154°/s for 0.5 GC, 218°/s for 1.0 GC, 254°/s for 1.33 GC). Subjects spent 60 s spinning at the specified constant velocity before performing a manual control task. On top of this rotating platform, the roll actuator rotated the subject about an Earth-vertical, head-centered axis about which the manual control task was performed (roll tilt in Fig. 1). The subject was instructed to keep his or her body aligned with the centripetal acceleration vector while being tilted leftward and rightward with respect to the subject’s frame of reference (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the experimental setup, with the chair positioned such that the subject’s head is 0.68 m from the center of rotation, the joystick is mounted in front of the subject’s chest, and the roll-tilt axis is centered at the level of the subject’s vestibular system. GIF, gravitoinertial force.

We emphasize that for this centrifuge the subject always rotated in the horizontal plane, and thus there were no dynamic cues resulting from movement relative to Earth gravity. Specifically, both the roll tilt axis and the centrifugation axis were parallel to gravity. The subject’s longitudinal (z) axis was perpendicular to both. Thus, despite the total gravitoinertial acceleration being >1 G, the only useful tilt displacement cue was the angle between the centripetal acceleration vector and the subject’s body longitudinal axis. One of the concerns with head rotations within a centrifuge environment is the Coriolis cross-coupled illusion (i.e., an illusory tumbling sensation that occurs when “out-of-plane” head tilts are made in the spinning environment; Guedry and Montague 1961; Jones 1970). However, since the head roll tilts/rotations occurred about an axis parallel to the centrifuge spin axis the illusion was not provoked. Additional considerations relevant to this configuration are detailed in discussion.

Manual control procedure.

To reduce nonvestibular motion cues, subjects were tested in complete darkness and wore long pants and long sleeves. Noise-canceling headphones played white noise during active roll tilt/rotation motions to mask auditory cues regarding device motion. Subjects also were provided with a microphone and were secured with a five-point harness. Foam pads were used for comfort and to evenly distribute haptic sensory cues. The subject’s head was immobilized by a head restraint, which consisted of two aluminum plates attached to a ratchet system that allowed the plates to be moved so that the subject’s head was firmly held. Thin (~1 cm), high-density foam was attached to the inside of the plates for subject comfort. Subjects were asked to report when the head was held firmly but comfortably.

Subjects were instructed as follows: “The chair will be tilting left and right randomly, and your goal will be to use the joystick to null out the motion. This means keeping the chair in its current configuration, not tilted to either side, so that it remains aligned with the rotation arm.” The joystick was a 30-cm-long rod that rotated about its midpoint and was located ~35 cm from the midriff of the seated subject. Subjects held the joystick at its central rotation axis such that no large hand or arm displacements were required to make control inputs. The joystick was spring loaded such that it tended to return to alignment with the subject’s body longitudinal axis and increased resistance proportional to deflection. The joystick could only be rotated in roll, and there were mechanical stops to limit deflections to ±45°/s. The subject was asked to use his/her dominant hand to hold the joystick (all subjects were right handed). The joystick deflection was recorded (Posital Fraba IXARC absolute optical rotary encoder) and was fed back into the roll tilt command (Fig. 2B). The joystick control dynamics were rate-control-attitude-hold, such that the amount of joystick deflection was proportional to the commanded roll rate of the cab (0.44°/s of roll rate was commanded per degree of joystick deflection, with a maximum commanded roll rate of 20°/s). Without any disturbance, if the joystick was not deflected from its center position, the chair would remain at its current roll orientation (sometimes referred to as attitude hold). These first-order dynamics (i.e., where the subject controls roll rate to null out roll angle) are typically easy to learn and can be mastered by subjects without relevant experience (i.e., nonpilots) (McRuer and Weir 1969). Software and actuation delays were less than human sensorimotor delays; the update rate for the feedback was 600 Hz, and the latency was 10–18 ms. Subjects familiarized themselves with the manual control task without centrifugation in the light before centrifugation began.

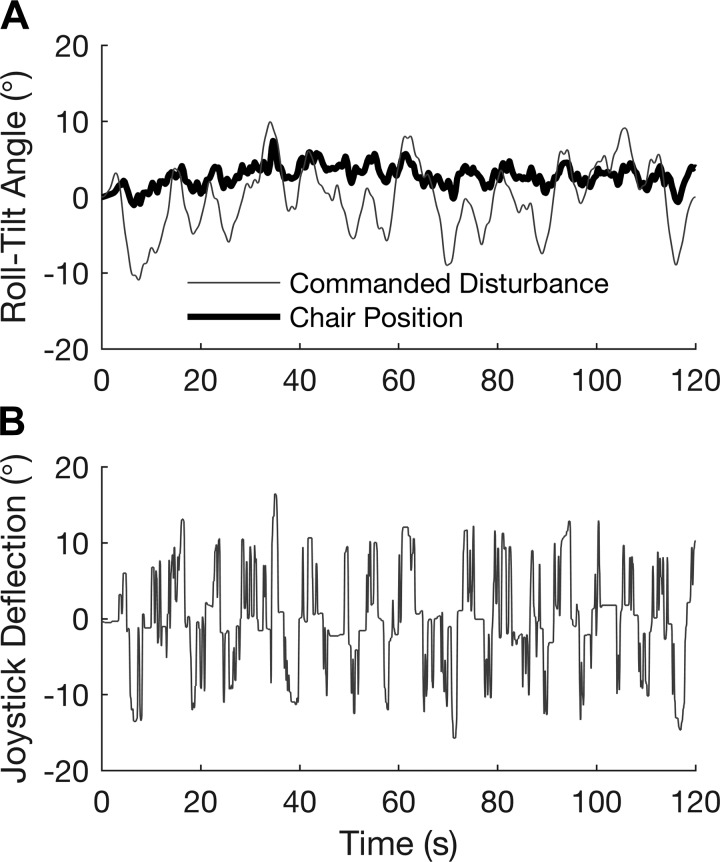

Fig. 2.

A: pseudorandom sum-of-sines roll-tilt disturbance profile (gray) and centrifuge chair position (black) for 1 trial of 1 subject. B: subject joystick deflection angle used for controlling chair orientation in a rate-control-attitude mode. The dynamics of subject inputs to the joystick were similar to those recently reported (Vimal et al. 2016).

As shown in Fig. 2, the roll-tilt disturbance was a pseudorandom zero-mean sum of sines made from 12 independent sinusoidal profiles, with characteristics similar to the motion profiles used in other studies (Clark et al. 2015a; Merfeld 1996). This profile was used for all trials and all conditions. The specific frequencies, phases, and amplitudes are shown in Table 2. A full trial was 120 s, with 5-s ramp-up and ramp-down phases at the beginning and end of the trial. The trial duration was selected to allow sufficient time to quantify performance yet be short enough to maintain subject focus. The chair roll-tilt motion was limited to ±15°. At these tilt limits, the chair would not continue to a larger angle but was free to move to a smaller angle. Potential confounds and strategic changes due to this limit are considered in results and discussion.

Table 2.

Frequencies, tilt amplitudes, and phases of pseudorandom sum of sines used to create roll-tilt disturbance motion profile

| Number | Frequency, Hz | Tilt Amplitude, ° | Phase, ° |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.018 | 2.65 | 112.5 |

| 2 | 0.027 | 2.65 | 75.7 |

| 3 | 0.046 | 2.65 | 65.0 |

| 4 | 0.064 | 2.65 | 127.1 |

| 5 | 0.100 | 2.65 | 44.9 |

| 6 | 0.155 | 2.65 | 170.1 |

| 7 | 0.209 | 0.26 | 192.7 |

| 8 | 0.264 | 0.26 | 152.7 |

| 9 | 0.336 | 0.26 | 25.7 |

| 10 | 0.427 | 0.26 | 78.5 |

| 11 | 0.536 | 0.26 | 24.7 |

| 12 | 0.664 | 0.26 | 116.0 |

Table 1 shows the experimental protocol for the two manual control subexperiments. Subjects performed three practice trials to get accustomed to the task in each GC condition (except in 1.0 GC in subexperiment 2, which had 9 practice trials because our protocol was still being refined). Analyses presented in results showed that there was no evidence of order or practice effects. After practice trials, subjects performed three manual control test trials. Subjects always performed 1.0 GC trials first. The centrifuge was accelerated over 120 s to the appropriate spin rate corresponding to the desired GC level. Then, after a period of at least 60 s of acclimatization, subjects performed practice and test trials as shown in Table 1. Between each trial, the subject had a 30-s break during which the chair was realigned with the centrifuge rotation arm. The centrifuge was then spun down to a stop over 60 s. Subjects had a 30-min break between conditions to prevent fatigue. Subexperiment 1 was completed before subexperiment 2 began, and thus subjects who participated in both always did subexperiment 1 first.

Roll-tilt vestibular perceptual direction-recognition thresholds.

Thresholds were estimated with methods identical to those we have recently used (Karmali et al. 2014; Valko et al. 2012), which are similar to those used by other groups (Benson et al. 1986, 1989; Butler et al. 2010; Crane 2012; Soyka et al. 2011). Subjects were seated upright on a Stewart-type six-degrees of freedom motion platform (MOOG CSA Engineering, Mountain View, CA; model 6DOF2000E). Thresholds were measured relative to Earth gravity (i.e., there was no centrifugation). As in the manual control tests, nonvestibular cues were reduced by testing in the dark, playing white noise in headphones, and having subjects wear long sleeves and pants. Although we call these “vestibular” thresholds, we acknowledge that proprioceptive or somatosensory cues may have some contribution. However, we note that subjects with bilateral vestibular ablation have thresholds two to four times higher than normal subjects for the threshold task used, suggesting the predominance of vestibular cues (Valko et al. 2012).

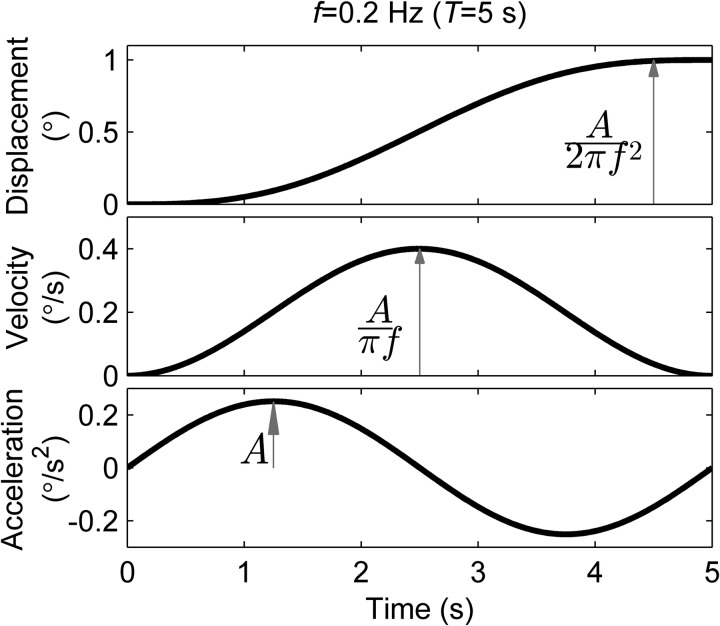

Test sessions consisted of 75–100 trials. Each trial was a leftward or rightward 0.2-Hz (5-s motion duration) single cycle sinusoid of acceleration (Fig. 3) about the head-centered roll-tilt axis (Lim et al. 2017). We selected roll tilt at 0.2 Hz because thresholds at this frequency depend on both otolith and semicircular canal contributions and because our manual control task likely relies upon both otolith and canal cues, based on the disturbance frequencies applied and subject reports about the strategy used. The brain performs integration of the two cues (Lim et al. 2017) to precisely distinguish between leftward and rightward motion, which is the most analogous to the integration required to perform our manual control task that also occurs in the roll-tilt plane. This truncated sinusoid concentrates the majority of energy at the stimulus frequency (Merfeld et al. 2016). Future studies might look at the relationship between manual control performance and otolith and canal thresholds separately to determine the relative contributions of each cue and also to investigate other tests such as subjective visual vertical.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of an example motion for a 0.2-Hz roll-tilt stimulus in the threshold task. A, acceleration; f, frequency; T, period.

Subjects heard white noise indicating that they were about to move, which continued throughout the motion profile. The end of the white noise indicated the end of motion, and subjects were asked to report their perceived direction of motion by pressing a left or a right button and to make their best guess if unsure. Subjects were tilted back to upright after they reported their perceived motion direction. A series of practice trials were given to the subjects beforehand to familiarize them with the motions and task.

The amplitudes of the motions were selected by a three-down, one-up adaptive staircase (Chaudhuri and Merfeld 2013; Leek 2001; Taylor and Creelman 1967), in which stimulus magnitude would decrease after three consecutive correct responses and would increase after one incorrect response. Using this adaptive sampling procedure with 75–100 trials yields reasonably low measurement error for the threshold parameter (i.e., with 100 trials the coefficient of variation is 18.5%; Karmali et al. 2016).

Data analysis.

Thresholds were determined with a cumulative Gaussian distribution psychometric curve fit relating stimulus amplitude to perceived motion direction (Chaudhuri et al. 2013; McCullagh and Nelder 1989). The cumulative Gaussian was selected based on use in previous work (Butler et al. 2010; MacNeilage et al. 2010; Roditi and Crane 2012; Soyka et al. 2011; Valko et al. 2012) and is defined by standard deviation (σ) and mean (μ). The mean of this curve fit represents the perceptual bias, the point at which a subject is equally likely to perceive a motion as leftward or rightward. One standard deviation of the distribution was defined as the subject’s threshold and is related to imprecision, or sensory noise, according to signal detection theory (Green and Swets 1966; Merfeld 2011). At this level, subjects will correctly identify 84% of stimuli. Psychometric curve fits were performed with the brglmfit.m function (Chaudhuri et al. 2013) in MATLAB 2014a (MathWorks, Natick, MA) which includes a generalized linear model and probit link function with improved parameter estimation for the case of serially dependent data points (Kaernbach 2001; Leek 2001; Leek et al. 1992; Treutwein and Strasburger 1999). To characterize manual control performance, we defined the position variability metric (PVM) as the standard deviation of the chair tilt angle over time, which indicated the precision of nulling. We excluded the first and last 5 s of each trial during which the disturbance was ramping up or down, leaving the middle 110 s. All statistics were performed with the middle 110 s and the full trial, and there was no substantial difference in the results. The metric was chosen because it directly corresponds to the definition of an 84% threshold, which is related by signal detection theory to the standard deviation of sensory noise (Green and Swets 1966). Specifically, both PVM and thresholds are measures of precision. It should be noted that these measures of precision are distinct from measures of accuracy (e.g., how close, on average, the chair is to upright). PVM was averaged across the three test trials in each GC condition.

All means, standard deviations, and tests of statistical significance were performed after taking the logarithm of the threshold and PVM. Population studies have shown that human vestibular thresholds follow a log-normal distribution (Benson et al. 1986, 1989; Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016). Since our hypothesis is that sensory noise is a critical determining factor of manual control PVM (also the standard deviation of performance), we expected PVM to be log-normally distributed as well. Statistical testing confirmed that the distributions of PVMs across subjects were not significantly different from a log-normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P = 0.75 for 1.0 GC, P = 0.996 for 1.33 GC, and P = 0.993 for 0.5 GC). Standard parametric comparisons (linear regression and paired t-test) were used to compare subjects’ thresholds and PVM along with mean PVM at different GC levels. Statistical tests were performed with the Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox in MATLAB 2016b (MathWorks).

Most analyses were done by fitting a linear mixed-effects model with threshold (log transformed) as a continuous predictor, subject as a random effect, GC level as a categorical predictor, and PVM (log transformed) as the dependent variable. GC was a categorical predictor so as not to impose an assumption of linearity between GC and PVM. For subjects who performed both subexperiments 1 and 2, the PVM for 1.0 GC was calculated as the average across the two sessions.

RESULTS

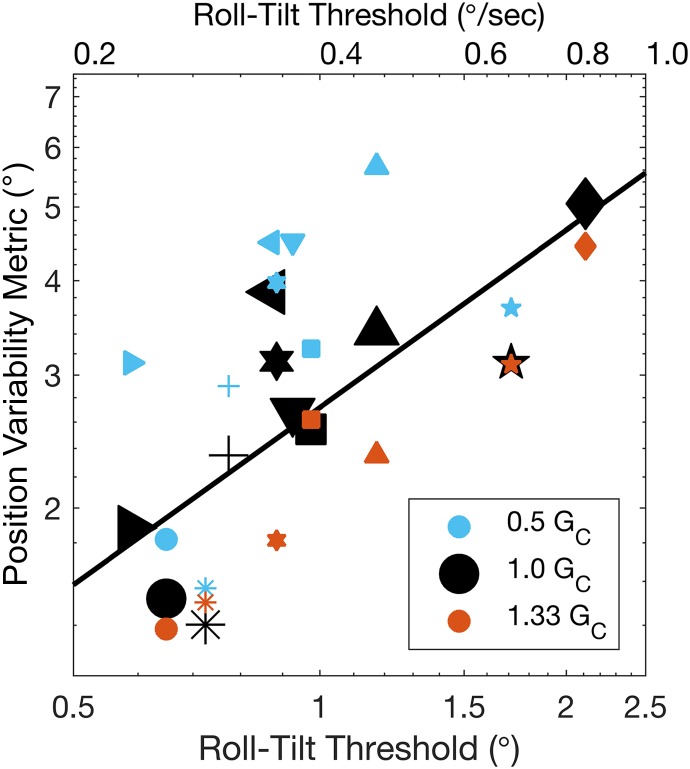

We found large intersubject differences in both thresholds and manual control performance. For example, across both subexperiments, thresholds (i.e., roll-tilt vestibular perceptual direction-recognition thresholds) ranged from 0.59° to 2.11° for the 11 subjects. It is common to report thresholds in terms of peak velocity in addition to net displacement. The range of thresholds presented as peak velocities is 0.24–0.84°/s for our 11 subjects. PVM had similarly large intersubject variation, ranging from 1.27° to 5.05° in 1.0 GC. For reference, the PVM of the chair motion without any joystick input was 4.58°.

Figure 4 presents the PVM as a function of threshold for all GC levels from both subexperiments, with individual subjects displayed with unique symbols. The following analyses were performed with the mixed-effect model described in methods. We found a significant, positive, linear influence of threshold on PVM [coefficient: 0.81 log units of degrees of PVM per log unit of threshold in degrees; t(24) = 5.66, P < 0.001], which is illustrated by the fit line. The coefficient of determination between log(threshold) and log(PVM) for 1.0 GC is R2 = 0.59 (P = 0.006). In addition, relative to the 1.0 GC condition, we found significant effects of 0.5 GC [coefficient: 0.12 log units of degrees of PVM; t(24) = 3.70, P = 0.001] and 1.33 GC [coefficient: −0.11 log units of degrees of PVM; t(24) = −3.2, P = 0.004]. Thus individuals with higher thresholds tended to have higher PVM (worse nulling performance), and PVM increased in 0.5 GC and decreased in 1.33 GC.

Fig. 4.

Manual control position variability metric as a function of threshold for each subject in 0.5 GC (centripetal acceleration), 1.0 GC, and 1.33 GC. Individual subjects are displayed with unique symbols.

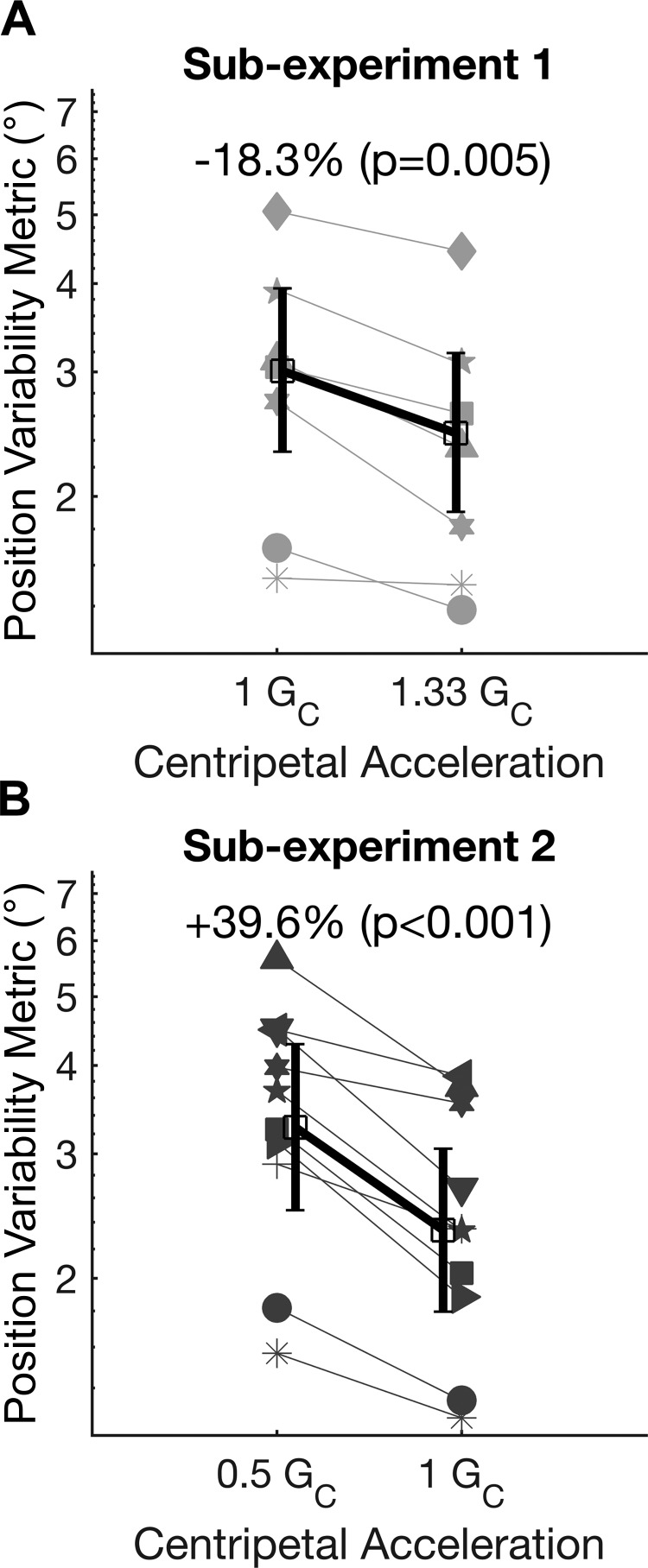

To study how the gravity environment may impact on manual control performance, the PVM in 1.0 GC was compared to the PVM in 1.33 GC for seven subjects in subexperiment 1 (Fig. 5A). Each individual subject (gray lines) is represented with a different symbol, corresponding to the symbols in Fig. 4. Averaged across all subjects (black line), the mean PVM in 1.33 GC was 18.3% lower than in 1.0 GC, which was statistically significant [paired t-test, t(6) = −4.4, P = 0.005].

Fig. 5.

A: manual control position variability metric (PVM) in 1.0 GC (centripetal acceleration) and 1.33 GC (subexperiment 1). Individual subjects are displayed in gray with unique symbols corresponding to Fig. 4. The intersubject mean is plotted in black, with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals. B: manual control PVM in 1.0 GC and 0.5 GC (subexperiment 2).

Figure 5B compares the PVM in 1.0 GC to the PVM in 0.5 GC for 10 subjects in subexperiment 2. Each individual subject (gray lines) is represented with a different symbol, corresponding to the symbols in Fig. 4. Averaged across all subjects (black line), the PVM in 0.5 GC is 39.6% higher than in 1.0 GC. This corresponds to subjects having significantly worse performance in 0.5 GC [paired t-test, t(9) = 6.8, P < 0.001].

We examined whether measurements were influenced by order of testing, by prior experience for subjects who participated in both subexperiments, and by task learning or practice effects. For subjects who did both subexperiments, we compared their 1.0 GC PVMs between the two sessions and found no evidence that it changed from the first session to the second session [paired t-test, t(5) = −0.2, P = 0.86], suggesting no effect of the prior experience. We also compared the PVMs for the second session of 1.0 GC with the PVMs for the subjects who were only tested once in 1.0 GC and found no significant difference between the two [unpaired t-test, t(9) = −0.7, P = 0.52]. Comparing PVMs in 0.5 GC between subjects who did and did not previously do the 1.33 GC condition, we found no significant difference between the two [unpaired t-test, t(8) = −0.2, P = 0.83]. To examine whether there were any residual learning or training effects present during the test trials, we looked for downward or upward trends in PVM across the three test trials. Specifically, we performed a repeated-measures ANOVA, with the trial numbers as the only factor. We found there to be no significant effect of trial number in 1.33 GC [F(2,12) = 2.09, P = 0.17], in 0.5 GC [F(2,18) = 0.29, P = 0.75], or in 1.0 GC before either condition [F(2,32) = 0.15, P = 0.87]. Together these results suggest that additional sources of measurement error or bias due to order or training effects were minimal.

We found that, on average, subjects were at the physical tilt limits of the device for 1.0% of the time (1.0% for 1.0 GC, 1.7% for 0.5 GC, 0.1% for 1.33 GC), and 10 of 11 subjects reached the limits at least once during testing trials. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether this affected the results by repeating the mixed-effect model analysis after excluding the chair position during the time that the chair was at the tilt limits. We found that the coefficient between PVM and threshold was 0.81 log units of degrees of PVM per log unit of threshold in degrees [t(24) = 5.62, P < 0.001]. In addition, relative to the 1.0 GC condition, we found significant effects of 0.5 GC [coefficient: 0.11 log units of degrees of PVM; t(24) = 3.64, P = 0.001] and 1.33 GC [coefficient: −0.11 log units of degrees of PVM; t(24) = −3.17, P = 0.004]. Thus there is no evidence that our conclusions arise from an artifact due to subjects reaching the tilt limit.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the relationship between vestibular perceptual thresholds and manual control performance. Manual control performance was tested in different artificial gravity environments created by short-arm centrifugation, specifically in 1.0 GC, 0.5 GC, and 1.33 GC, whereas thresholds were measured with the subject upright relative to Earth’s gravity. We found that 1) there was a strong, statistically significant, linear correlation between an individual’s log of roll-tilt 0.2 Hz threshold and the log of manual control PVM; 2) manual control performance was consistently and significantly worse in 0.5 GC than in 1.0 GC; and 3) manual control performance was significantly improved in 1.33 GC compared with 1.0 GC performance. We note that our measurements were made with <15 min of exposure to an altered gravity environment, and thus they do not aim to characterize anatomical (Boyle et al. 2010) and behavioral (Paloski et al. 2008) adaptations that have been demonstrated during longer-term exposure to altered gravity environments.

Vestibular precision affects manual control performance.

The correlation between manual control performance and threshold suggests that vestibular precision determined performance. Since thresholds reflect random neural activity (i.e., no functional information conveyed) (Green and Swets 1966; Merfeld 2011) that originates at every stage of neural processing (Faisal et al. 2008), it is important to examine which sources of neural imprecision (e.g., sensory, central, motor) contribute to behavioral imprecision. Our results are aligned with other work showing that sensory noise is an important contributor to perceptual and motor imprecision (Haburcakova et al. 2012; Liston and Krauzlis 2003; Medina and Lisberger 2007; Nouri and Karmali 2018; Osborne et al. 2005; Rasche and Gegenfurtner 2009; Schoppik et al. 2008; Stone and Krauzlis 2003). Our results suggest that manual control imprecision occurs because of noise originating in the sensory periphery or early in central processing, rather than being dominated by other sources, such as motor noise; of course, we cannot rule out a smaller contribution from these sources. Emphasizing the relationship between our measurements, we calculated PVM as the standard deviation of manual control system response, and, similarly, thresholds reflect the standard deviation of sensory noise. These noise measures are also equivalent to those used in stochastic models of dynamic spatial orientation (Borah et al. 1988; Karmali et al. 2018; Karmali and Merfeld 2012; Laurens and Angelaki 2017; Lim et al. 2017) and postural control (Assländer and Peterka 2016; Goodworth et al. 2018; van der Kooij et al. 1999, 2001; van der Kooij and Peterka 2011), and future work could extend these models to stochastic closed-loop manual control tasks. Demonstrating the broader utility of precision measures, we also note that roll-tilt and linear translation vestibular perceptual thresholds have been shown to be sensitive to disorders such as vestibular migraine and Ménière’s disease (Bremova et al. 2016; Lewis et al. 2011).

Although our sample consisted of only 11 people, statistical testing found that the results were unlikely to have arisen by chance, providing confidence in the conclusions. The moderate sample size was constrained by the expense of performing these experiments (including device utilization fees and roughly 10 person-hours of operator time per subject per condition). The subject group was also relatively homogeneous and included mostly young individuals who passed the screening. Although we do not claim that our study generalizes to older individuals, it does indicate the need for future studies in light of two recent findings. First, we found that both age and vestibular perceptual thresholds make substantial contributions to balance test performance (Karmali et al. 2017). Second, roll-tilt thresholds were 2.7× higher for a group of subjects of 60–80 yr vs. 30–39 yr (Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016).

There are factors other than sensory precision that likely affect PVM. These include the time it takes to sense tilt, the error and delay in mapping the sensation to a motor control action, the time it takes to perform that motor action, the time for the chair to move, and the difference between the frequency dynamics of the operator and the disturbance. Time delays allow errors to propagate throughout the period after initial stimulation.

All motions used in this study were about a head-centered roll-tilt axis. On the basis of our results, we hypothesize that our results would generalize to other axes, e.g., there would be a correlation between translation thresholds and translation manual control.

Manual control in altered gravity environments.

We now discuss our findings in relation to other published studies on manual control in altered gravity environments. Clark et al. (2015a) studied manual control performance in a hypergravity environment created by a long-arm centrifuge and found an initial performance decrement proportional to gravity level that improved within a few minutes. As in our study, subjects controlled roll-tilt motion with a joystick in the presence of a disturbance, but the cab tilted relative to the gravitoinertial acceleration (i.e., the net direction of the sum of gravity and centripetal acceleration, G) rather than relative to centripetal acceleration (GC). In subjects well trained to perform the manual control task in Earth gravity, when performance stabilized after ~600 s of doing the task in hyper-G, the authors did not report a statistically significant difference between hypergravity performance (1.5 and 2.0 G) and 1.0 G baseline. Nonetheless, there was a trend toward better steady-state performance in 1.5 G vs. 1.0 G, although such a trend was not obviously apparent in 2.0 G. This lack of a significant effect of G level on steady-state manual control performance may result from differences in the methods vs. our study, including 1) the use of an exponential decay model to identify steady-state performance as opposed to using only test trials that occurred after sufficient practice; 2) the potential presence of Coriolis cross-coupling illusions due to the tilt axis not being aligned with the spin axis; 3) testing relative to the gravitoinertial acceleration vs. the centripetal acceleration; 4) testing at different G levels; and 5) the use of longer (214.8 s) trials. Despite these differences, the trends observed in Clark et al. (2015a) are consistent with the statistically significant better performance in 1.33 GC vs. 1.0 GC that we found. To our knowledge, the only other study of roll-tilt manual control related to altered gravity (Merfeld 1996) studied astronauts before and after exposure to microgravity. Because measurements were not made in altered gravity, it is difficult to compare those results to our study. Future work will be required to separate the various contributors to these changes, including the reinterpretation of otolith cues in microgravity (Young et al. 1984).

The impact of the otolith organ cue in the horizontal plane that is relevant to the task might be explained through simple geometry. The effective mechanical stimulus to the otolith organ is considered to be the “shear component” of the gravitoinertial force, acting in the dominant plane of the utricular macula (Clark et al. 2015c; Schoene 1964; Young 1982). For any tilt angle, this otolith organ cue is diminished when gravitational forces are reduced. This is supported by our recent work that found that perception of roll tilt is underestimated in a hypogravity analog (Galvan-Garza et al. 2018). Likewise, we assume that noise is relatively unchanged, although future studies could investigate whether noise varies with GC by performing the threshold task during centrifugation. Thus in hypogravity (e.g., 0.5 GC) the shear signal is diminished while presumably the noise is unchanged, resulting in a reduced signal-to-noise ratio. In hypergravity, however, the shear force at any tilt angle is increased, resulting in an increased signal-to-noise ratio. Even if the brain properly interprets the otolith signal in altered gravity, this change in signal-to-noise ratio regarding tilt information likely explains the observed impaired manual control performance in our nulling task. Similar logic applies to other graviceptors, although evidence suggests that vestibular cues are the primary graviceptive cue for threshold-level motion (Valko et al. 2012). Functionally, the reduced signal-to-noise ratio in 0.5 GC causes the subject to require a larger tilt angle before he/she can reliably determine the corrective joystick response. This translates into an increased range of the “dead zone” where subjects cannot reliably sense tilt and thus cannot null the motion. Conversely, in 1.33 GC, the otolith signal is amplified for a given tilt, increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. This allows the subject to reliably perceive smaller tilt angles, increasing the ability to detect changes early and react. While evidence suggests that the brain relies on the lateral (i.e., interaural) component of the gravitational vector sensed by the otolith organ to determine tilt angle (Clark et al. 2015c; Schoene 1964; Young 1982), this reasoning is independent of the mechanism used to determine tilt angle from the three-dimensional vector sensed by the otolith organ.

Subjects occasionally reached the physical tilt limits of the device. Our analyses showed that this had a marginal impact on the conclusions of the study. It is possible that the limits influenced perception since subjects were aware that only a narrow range of tilt was possible. However, unlike some studies in which prior knowledge affects tilt perception via Bayesian inference (Alberts et al. 2016), we cannot think of a mechanism by which subjects could improve precision based on knowledge of the device limits, since avoiding the limits and aligning with upright accomplish similar goals.

Individual differences and hypogravity effects.

We found large individual differences in roll-tilt 0.2 Hz thresholds ranging from 0.59° to 2.11°, which is consistent with a previous study using identical methods that found a range of roll-tilt 0.2 Hz thresholds from 0.375° to 2.7° across 95% of healthy subjects (Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016). Similarly, there is a high degree of intersubject variability in manual control. PVM ranged from 1.27° to 5.05° in 1.0 GC. The individual differences in threshold contribute much more to variations in performance than GC level (Fig. 4), which changed only 36% between 0.5 GC and 1.0 GC. In comparison, the expected PVM for the subject with the highest threshold is 298% of that for the subject with the lowest threshold, emphasizing that individual differences have a larger effect on PVM than GC levels.

Centrifuge configuration.

The centrifuge configuration used for this study (which to our knowledge is novel for human studies) should have applications for certain classes of studies; we now discuss relevant considerations. Although short-radius and long-radius centrifuge paradigms have been used to study human performance in hypergravity environments (e.g., Clark et al. 2015a, 2015b; Glasauer and Mittelstaedt 1992; Schoene 1964; Tribukait and Eiken 2005), it is not possible to study a pure hypogravity environment on Earth because of the presence of Earth’s gravitational field. However, our hypogravity analog allows for studies in which the centripetal acceleration cue relevant to the task is <1.0 GC. Although Earth’s gravity is statically present, it does not provide a useful roll-tilt cue to the subject and was consistently present across all GC conditions. Therefore, the ability to null the pseudorandom disturbance is only dependent on the magnitude of tilt perceived relative to the centripetal acceleration. This approach would not be appropriate for studies in which the total force is likely more important than the longitudinal force. Although only the centripetal acceleration is a useful task cue for the subject, the cognitive experience of the subject is somewhat more complex, since he/she would be expected to perceive a somatogravic pitch tilt out of the horizontal plane that aligns with the net gravitoinertial acceleration. For example, with 0.5 GC and 1 G gravity, the subject would perceive a head-down pitch tilt of 26°. Furthermore, when the subject roll tilts relative to centrifuge axis, there is a slight reduction in the component of centripetal acceleration along the subject’s longitudinal axis, which causes the somatogravic pitch tilt to reduce slightly, ~1° of pitch for 10° of roll tilt. Future studies will be needed to determine whether the presence of Earth gravity affects results, which could include parabolic flight studies (Karmali and Shelhamer 2008), which provide a net gravitoinertial acceleration between 0 and 1 G. Another distinguishing attribute of this configuration is that there was no Coriolis cross-coupling illusion, in contrast with configurations that align the subject with the total gravitoinertial acceleration. In our configuration, subjects experienced some wind cues, although these could be diminished in future studies by enclosing the subject. This centrifuge configuration would be particularly relevant to characterizing piloting during landing or ascent, locomotion, orientation perception, and cardiovascular responses for conditions on or near the surface of the moon or Mars.

Relevance and applications.

We now describe the relevance and eventual applications of this line of research.

Our results are related to a growing body of research suggesting that sensory imprecision worsens postural performance. Manual control and postural control are similar in that both use closed-loop feedback control and are approximated by a single-link inverted pendulum (Panic et al. 2015; Riccio et al. 1992). Modeling of postural responses to perturbations with closed-loop models suggests that postural variability and sway arise from imprecision in vestibular sensation, vision, proprioception, and muscle control (Goodworth et al. 2018; Mergner et al. 2005; Peterka 2002; van der Kooij et al. 1999, 2001; van der Kooij and Peterka 2011). Furthermore, age and vestibular roll-tilt 0.2 Hz thresholds are both correlated (using a multiple variable logistic regression) with pass/fail performance in a balance test in which subjects are asked to stand on foam with eyes closed (Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016; Karmali et al. 2017). Our results build on these studies showing that sensory precision underlies functional performance, specifically by providing experimental evidence of a continuous (vs. pass/fail) relationship between thresholds and performance. This has potential public health relevance given that postural errors are correlated with debilitating falls (Overstall et al. 1977) and sensory precision is an incompletely understood source of postural errors.

Errors in sensing motion and orientation have contributed and continue to contribute to many fatal aviation accidents (Gibb et al. 2011). Substantial risks have also been identified for manned spacecraft landings, and near-miss incidents have occurred (Karmali and Shelhamer 2010; McCluskey et al. 2001; Moore et al. 2008; Paloski et al. 2008). Paloski et al. (2008) state that “neuro-vestibular dysfunction [is] generally correlated with poorer flying performance, including a lower approach and landing shorter, faster and harder.” If vestibular precision is indeed a critical factor in vehicle control performance, then our approach could provide a tool to predict which individuals may have enhanced piloting performance, which could reduce risk. This is especially important given the potential synergistic risk arising from hypogravity and individuals with high thresholds. Of course, vision also plays a critical role, and further research is required to understand the relative contributions of visual and vestibular cues. Notably, vestibular roll-tilt thresholds are lower than visual roll-tilt thresholds for certain temporally frequencies, and even when visual thresholds are lower vestibular cues still contribute to visual-vestibular precision via Bayesian integration (Karmali et al. 2014). Thus, even with visual cues available, individual differences in vestibular precision could potentially still contribute to differences in manual control performance. Future investigations will be required to determine how these effects combine with adaptation to a novel gravity environment and long-term compensatory adaptation mechanisms that may also affect performance. We further note that the joystick rate-control-attitude-hold control dynamics used in this study were similar to those of a helicopter or a lunar landing vehicle.

Astronauts walking on the surface of the moon experienced a large number of falls, which placed them at risk of injury. Considering that balance test performance is correlated with roll-tilt 0.2 Hz thresholds (Bermúdez Rey et al. 2016; Karmali et al. 2017), PVM is correlated with roll-tilt 0.2 Hz thresholds, and PVM is diminished in hypogravity, a reasonable prediction is that diminished postural control on the moon or Mars occurs because of diminished vestibular sensation. There could also be a potential interaction with a motion sickness drug commonly used by astronauts, promethazine, which also increases roll-tilt 0.2 Hz thresholds (Diaz-Artiles et al. 2017). These factors may be exacerbated because visual tilt perception is difficult on the moon (Brady and Paschall 2010).

While speculative, to illustrate that large intersubject differences may have operational relevance and modulate risks, we provide an example from piloting a helicopter. This example does not consider the impact of visual cues, as could occur in certain brown-out or white-out conditions (e.g., obscuration by sand, dust, or snow). The critical rollover angle for a helicopter is between 5° and 8° (Department of Transportation 2012). Our worst performer has a PVM of 5.05°, which, assuming a Gaussian distribution with a standard deviation of 5.05°, corresponds roughly to a 6% chance of experiencing a tilt greater than 8° when intending to be upright. On the other hand, the best performer has a PVM of 1.27°, corresponding to <0.0001% chance of exceeding a tilt of 8° when intending to be upright. Thus risk might be mitigated by assigning pilots with lower thresholds, if our laboratory results transfer to real-world piloting tasks. A similar analysis applies to moon/Mars landings; the Apollo lunar module was required to land with <11° of roll tilt to ensure a successful ascent launch (Rogers 1972).

Summary.

In this study, we demonstrated a relationship between an individual’s roll-tilt vestibular perceptual threshold and his/her performance in a manual control task. This suggests that sensory precision is a critical determining factor in manual control performance. Using a short-radius centrifuge, we also showed that, as expected, performance was better in 1.33 GC vs. 1.0 GC and worse in 0.5 GC vs. 1.0 GC. The performance decrement observed in hypogravity is particularly relevant for future human exploration missions to the moon and Mars, where gravity is less than on Earth, potentially increasing risk during piloted landing, standing balance, and locomotion.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute through National Aeronautics and Space Administration Cooperative Agreement NCC 9-58 and by the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders through Grant DC-013635 (F. Karmali).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.J.R., R.C.G.-G., T.K.C., and D.P.S. performed experiments; M.J.R., R.C.G.-G., D.P.S., and F.K. analyzed data; M.J.R., R.C.G.-G., T.K.C., and F.K. interpreted results of experiments; M.J.R. and F.K. prepared figures; M.J.R. drafted manuscript; M.J.R., R.C.G.-G., T.K.C., L.R.Y., and F.K. edited and revised manuscript; M.J.R., R.C.G.-G., T.K.C., D.P.S., L.R.Y., and F.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the participation of all our subjects. We credit Dr. Dan Merfeld and Dr. Lionel Zupan for conceptualizing and designing the centrifuge configuration used in this study. We thank the Jenks Vestibular Physiology Lab for the use of the MOOG and Eccentric Rotator devices and Dr. Dan Merfeld for scientific insight and assistance in using his devices. Portions of these results were included in the report submitted by M. J. Rosenberg and supervised by F. Karmali in fulfillment of Master’s degree requirements.

REFERENCES

- Alberts BB, de Brouwer AJ, Selen LP, Medendorp WP. A Bayesian account of visual-vestibular interactions in the rod-and-frame task. eNeuro 3: ENEURO.0093-0016.2016, 2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0093-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assländer L, Peterka RJ. Sensory reweighting dynamics following removal and addition of visual and proprioceptive cues. J Neurophysiol 116: 272–285, 2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.01145.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AJ, Hutt EC, Brown SF. Thresholds for the perception of whole body angular movement about a vertical axis. Aviat Space Environ Med 60: 205–213, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AJ, Spencer MB, Stott JR. Thresholds for the detection of the direction of whole-body, linear movement in the horizontal plane. Aviat Space Environ Med 57: 1088–1096, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez Rey MC, Clark TK, Wang W, Leeder T, Bian Y, Merfeld DM. Vestibular perceptual thresholds increase above the age of 40. Front Neurol 7: 162, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah J, Young LR, Curry RE. Optimal estimator model for human spatial orientation. Ann NY Acad Sci 545: 51–73, 1988. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb19555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolami SB, Rocca S, Daros S, DiZio P, Lackner JR. Mechanisms of human static spatial orientation. Exp Brain Res 173: 374–388, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle R, Popova Y, Varelas J, Mofrad A. Neurovestibular adaptation in the utricular otolith in fish to hypergravity exposure and re-adaptation to 1G. 38th COSPAR Scientific Assembly Bremen, Germany, July 18–25 2010, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Brady T, Paschall S. The challenge of safe lunar landing. In: 2010 IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings. New York: IEEE, 2010, p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bremova T, Caushaj A, Ertl M, Strobl R, Böttcher N, Strupp M, MacNeilage PR. Comparison of linear motion perception thresholds in vestibular migraine and Menière’s disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273: 2931–2939, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3835-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JS, Smith ST, Campos JL, Bülthoff HH. Bayesian integration of visual and vestibular signals for heading. J Vis 10: 23, 2010. doi: 10.1167/10.11.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri SE, Karmali F, Merfeld DM. Whole body motion-detection tasks can yield much lower thresholds than direction-recognition tasks: implications for the role of vibration. J Neurophysiol 110: 2764–2772, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.00091.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri SE, Merfeld DM. Signal detection theory and vestibular perception: III. Estimating unbiased fit parameters for psychometric functions. Exp Brain Res 225: 133–146, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3354-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TK, Newman MC, Merfeld DM, Oman CM, Young LR. Human manual control performance in hyper-gravity. Exp Brain Res 233: 1409–1420, 2015a. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TK, Newman MC, Oman CM, Merfeld DM, Young LR. Human perceptual overestimation of whole body roll tilt in hypergravity. J Neurophysiol 113: 2062–2077, 2015b. doi: 10.1152/jn.00095.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TK, Newman MC, Oman CM, Merfeld DM, Young LR. Modeling human perception of orientation in altered gravity. Front Syst Neurosci 9: 68, 2015c. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane BT. Direction specific biases in human visual and vestibular heading perception. PLoS One 7: e51383, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vrijer M, Medendorp WP, Van Gisbergen JA. Accuracy-precision trade-off in visual orientation constancy. J Vis 9: 1–15, 2009. doi: 10.1167/9.2.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Transportation Helicopter Flying Handbook. Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration, 2012, p. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Artiles A, Priesol AJ, Clark TK, Sherwood DP, Oman CM, Young LR, Karmali F. The impact of oral promethazine on human whole-body motion perceptual thresholds. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 18: 581–590, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10162-017-0622-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal AA, Selen LP, Wolpert DM. Noise in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 292–303, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nrn2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, Goldberg JM. Physiology of peripheral neurons innervating semicircular canals of the squirrel monkey. II. Response to sinusoidal stimulation and dynamics of peripheral vestibular system. J Neurophysiol 34: 661–675, 1971. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan-Garza RC, Clark TK, Sherwood D, Diaz Artiles A, Rosenberg MJ, Natapoff A, Karmali F, Oman CM, Young LR. Human perception of whole-body roll tilt orientation in a hypo-gravity analog: underestimation and adaptation. J Neurophysiol. 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00140.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb R, Ercoline B, Scharff L. Spatial disorientation: decades of pilot fatalities. Aviat Space Environ Med 82: 717–724, 2011. doi: 10.3357/ASEM.3048.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasauer S, Mittelstaedt H. Determinants of orientation in microgravity. Acta Astronaut 27: 1–9, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0094-5765(92)90167-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodworth AD, Tetreault K, Lanman J, Klidonas T, Kim S, Saavedra S. Sensorimotor control of the trunk in sitting sway referencing. J Neurophysiol 120: 37–52, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00330.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr L, Nicoucar K, Mast FW, Merfeld DM. Vestibular thresholds for yaw rotation about an earth-vertical axis as a function of frequency. Exp Brain Res 186: 677–681, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. New York: Wiley, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Guedry FE, Montague E. Quantitative evaluation of vestibular Coriolis reaction. Aerosp Med 32: 487–500, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Haburcakova C, Lewis RF, Merfeld DM. Frequency dependence of vestibuloocular reflex thresholds. J Neurophysiol 107: 973–983, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00451.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)-planning, collecting and managing data for clinical and translational research (Abstract). BMC Bioinformatics 13, Suppl 12: A15, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S12-A15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamali M, Sadeghi SG, Cullen KE. Response of vestibular nerve afferents innervating utricle and saccule during passive and active translations. J Neurophysiol 101: 141–149, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.91066.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GM. Origin significance and amelioration of coriolis illusions from the semicircular canals: a non-mathematical appraisal. Aerosp Med 41: 483–490, 1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaernbach C. Slope bias of psychometric functions derived from adaptive data. Percept Psychophys 63: 1389–1398, 2001. doi: 10.3758/BF03194550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Bermúdez Rey MC, Clark TK, Wang W, Merfeld DM. Multivariate analyses of balance test performance, vestibular thresholds, and age. Front Neurol 8: 578, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Chaudhuri SE, Yi Y, Merfeld DM. Determining thresholds using adaptive procedures and psychometric fits: evaluating efficiency using theory, simulations, and human experiments. Exp Brain Res 234: 773–789, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Lim K, Merfeld DM. Visual and vestibular perceptual thresholds each demonstrate better precision at specific frequencies and also exhibit optimal integration. J Neurophysiol 111: 2393–2403, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00332.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Merfeld DM. A distributed, dynamic, parallel computational model: the role of noise in velocity storage. J Neurophysiol 108: 390–405, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00883.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Shelhamer M. The dynamics of parabolic flight: flight characteristics and passenger percepts. Acta Astronaut 63: 594–602, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Shelhamer M. Neurovestibular considerations for sub-orbital space flight: a framework for future investigation. J Vestib Res 20: 31–43, 2010. 10.3233/VES-2010-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali F, Whitman GT, Lewis RF. Bayesian optimal adaptation explains age-related human sensorimotor changes. J Neurophysiol 119: 509–520, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00710.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurens J, Angelaki DE. A unified internal model theory to resolve the paradox of active versus passive self-motion sensation. eLife 6: e28074, 2017. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurens J, Droulez J. Bayesian processing of vestibular information. Biol Cybern 96: 389–404, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00422-006-0133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek MR. Adaptive procedures in psychophysical research. Percept Psychophys 63: 1279–1292, 2001. doi: 10.3758/BF03194543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek MR, Hanna TE, Marshall L. Estimation of psychometric functions from adaptive tracking procedures. Percept Psychophys 51: 247–256, 1992. doi: 10.3758/BF03212251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RF, Priesol AJ, Nicoucar K, Lim K, Merfeld DM. Abnormal motion perception in vestibular migraine. Laryngoscope 121: 1124–1125, 2011. doi: 10.1002/lary.21723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K, Karmali F, Nicoucar K, Merfeld DM. Perceptual precision of passive body tilt is consistent with statistically optimal cue integration. J Neurophysiol 117: 2037–2052, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00073.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston D, Krauzlis RJ. Shared response preparation for pursuit and saccadic eye movements. J Neurosci 23: 11305–11314, 2003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11305.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeilage PR, Banks MS, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Vestibular heading discrimination and sensitivity to linear acceleration in head and world coordinates. J Neurosci 30: 9084–9094, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1304-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeilage PR, Ganesan N, Angelaki DE. Computational approaches to spatial orientation: from transfer functions to dynamic Bayesian inference. J Neurophysiol 100: 2981–2996, 2008. doi: 10.1152/jn.90677.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey R, Clark JB, Stepaniak P. Correlation of space shuttle landing performance with cardiovascular and neurovestibular dysfunction resulting from space flight. In: Human Systems 2001. Houston, TX: NASA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1989, p. 532. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-3242-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McRuer D, Weir DH. Theory of manual vehicular control. Ergonomics 12: 599–633, 1969. doi: 10.1080/00140136908931082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Lisberger SG. Variation, signal, and noise in cerebellar sensory-motor processing for smooth-pursuit eye movements. J Neurosci 27: 6832–6842, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1323-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merfeld DM. Effect of spaceflight on ability to sense and control roll tilt: human neurovestibular studies on SLS-2. J Appl Physiol (1985) 81: 50–57, 1996. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merfeld DM. Signal detection theory and vestibular thresholds: I. Basic theory and practical considerations. Exp Brain Res 210: 389–405, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2557-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merfeld DM, Clark TK, Lu YM, Karmali F. Dynamics of individual perceptual decisions. J Neurophysiol 115: 39–59, 2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.00225.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T, Schweigart G, Maurer C, Blümle A. Human postural responses to motion of real and virtual visual environments under different support base conditions. Exp Brain Res 167: 535–556, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelstaedt H. Somatic graviception. Biol Psychol 42: 53–74, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(95)05146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore ST, MacDougall HG, Lesceu X, Speyer JJ, Wuyts F, Clark JB. Head-eye coordination during simulated orbiter landing. Aviat Space Environ Med 79: 888–898, 2008. doi: 10.3357/ASEM.2209.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri S, Karmali F. Variability in the vestibulo-ocular reflex and vestibular perception. Neuroscience. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne LC, Lisberger SG, Bialek W. A sensory source for motor variation. Nature 437: 412–416, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstall PW, Exton-Smith AN, Imms FJ, Johnson AL. Falls in the elderly related to postural imbalance. BMJ 1: 261–264, 1977. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6056.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloski WH, Oman CM, Bloomberg JJ, Reschke MF, Wood SJ, Harm DL, Peters BT, Mulavara AP, Locke JP, Stone LS. Risk of sensory-motor performance failures affecting vehicle control during space missions: a review of the evidence. J Gravit Physiol 15: 1–29, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Panic H, Panic AS, DiZio P, Lackner JR. Direction of balance and perception of the upright are perceptually dissociable. J Neurophysiol 113: 3600–3609, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00737.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulin MG, Nelson ME, Bower JM. Dynamics of compensatory eye movement control: an optimal estimation analysis of the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Int J Neural Syst 01: 23–29, 1989. doi: 10.1142/S0129065789000426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterka RJ. Sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J Neurophysiol 88: 1097–1118, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasche C, Gegenfurtner KR. Precision of speed discrimination and smooth pursuit eye movements. Vision Res 49: 514–523, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio GE, Martin EJ, Stoffregen TA. The role of balance dynamics in the active perception of orientation. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 18: 624–644, 1992. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.18.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roditi RE, Crane BT. Suprathreshold asymmetries in human motion perception. Exp Brain Res 219: 369–379, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3099-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers WF. Apollo Lunar Module Landing Gear. Houston, TX: NASA, 1972, p. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi SG, Chacron MJ, Taylor MC, Cullen KE. Neural variability, detection thresholds, and information transmission in the vestibular system. J Neurosci 27: 771–781, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4690-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoene H. On the role of gravity in human spatial orientation. Aerosp Med 35: 764–772, 1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppik D, Nagel KI, Lisberger SG. Cortical mechanisms of smooth eye movements revealed by dynamic covariations of neural and behavioral responses. Neuron 58: 248–260, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemungal BM, Gunaratne IA, Fleming IO, Gresty MA, Bronstein AM. Perceptual and nystagmic thresholds of vestibular function in yaw. J Vestib Res 14: 461–466, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka F, Robuffo Giordano P, Beykirch K, Bülthoff HH. Predicting direction detection thresholds for arbitrary translational acceleration profiles in the horizontal plane. Exp Brain Res 209: 95–107, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2523-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS, Krauzlis RJ. Shared motion signals for human perceptual decisions and oculomotor actions. J Vis 3: 725–736, 2003. doi: 10.1167/3.11.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarnutzer AA, Bockisch C, Straumann D, Olasagasti I. Gravity dependence of subjective visual vertical variability. J Neurophysiol 102: 1657–1671, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.00007.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MM, Creelman CD. PEST: efficient estimates on probability functions. J Acoust Soc Am 41: 782–787, 1967. doi: 10.1121/1.1910407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treutwein B, Strasburger H. Fitting the psychometric function. Percept Psychophys 61: 87–106, 1999. doi: 10.3758/BF03211951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribukait A, Eiken O. Semicircular canal contribution to the perception of roll tilt during gondola centrifugation. Aviat Space Environ Med 76: 940–946, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko Y, Lewis RF, Priesol AJ, Merfeld DM. Vestibular labyrinth contributions to human whole-body motion discrimination. J Neurosci 32: 13537–13542, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2157-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij H, Jacobs R, Koopman B, Grootenboer H. A multisensory integration model of human stance control. Biol Cybern 80: 299–308, 1999. doi: 10.1007/s004220050527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij H, Jacobs R, Koopman B, van der Helm F. An adaptive model of sensory integration in a dynamic environment applied to human stance control. Biol Cybern 84: 103–115, 2001. doi: 10.1007/s004220000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij H, Peterka RJ. Non-linear stimulus-response behavior of the human stance control system is predicted by optimization of a system with sensory and motor noise. J Comput Neurosci 30: 759–778, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s10827-010-0291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vimal VP, Lackner JR, DiZio P. Learning dynamic control of body roll orientation. Exp Brain Res 234: 483–492, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00221-015-4469-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LR. Perception of the body in space: mechanisms. In: Handbook of Physiology, The Nervous System, Sensory Processes Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society, 1984, p. 1023–1066. doi: 10.1002/cphy.cp010322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young LR, Oman CM, Watt DG, Money KE, Lichtenberg BK. Spatial orientation in weightlessness and readaptation to earth’s gravity. Science 225: 205–208, 1984. doi: 10.1126/science.6610215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]