Abstract

Objectives

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are used beside disease-oriented outcomes (e.g., number of teeth, clinical attachment level) to better capture diseases’ or interventions’ impacts. To assess PROs for dental patients (dPROs), dental patient-reported outcome measures (dPROMs) are applied. The aim of this systematic review was to identify generic dPROMs for adult patients and their dPROs.

Methods

This systematic review searched the MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO databases along with hand searching, through December 2017, to identify English-language, multi-item dPROMs that are oral health-generic, i.e., they are applicable to a broad range of adult patients.

Results

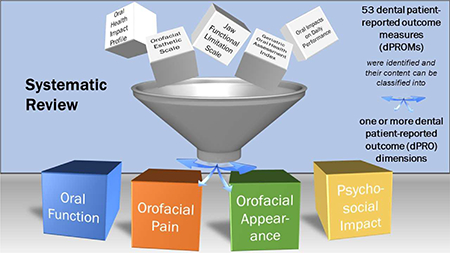

We identified 20 questionnaires, which contained 36 unique dPROs. They were measured by 53 dPROMs. dPRO names (N=36) suggested they could be grouped into four dPRO categories: Oral Function (N=11), Orofacial Pain (N=7), Orofacial Appearance (N=3), and Psychosocial Impact (N=14) and an additional dPRO that represented perceived oral health in general. Only eight questionnaires had a specific recall or reference period. dPROM’s score dimensionality was only investigated in 13 of the 20 questionnaires.

Conclusions

The identified 36 dPROs represent the major aspects of an adult dental patient’s oral health experience; however, four major dPRO groupings, i.e., Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact, summarize how patients are impacted. If multi-item, oral health-generic dPROMs are to be used to measure patients’ suffering, the 53 dPROMs represent current available tools. Limitations of the majority of these dPROMs include incomplete knowledge about their dimensionality, which affects their validity, and an unspecified recall period, which reduces their clinical applicability.

Keywords: Oral health, Quality of life, Questionnaire, Patient-reported outcome, Patient-reported outcome measure, Dimensionality

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Researchers and oral health professionals increasingly use patient-oriented or patient-reported outcomes (PROs)1 beside disease-oriented outcomes (e.g., number of teeth, clinical attachment level) to better capture diseases and interventions’ impact on the patient. A PRO is defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”2 Most PROs assess (i) status of the patient’s health condition, (ii) health behaviors, or (iii) experience with health care, with the first category being the largest group because they are often used to study treatment effects. To assess a PRO, a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) is used. The most widely used PROMs have multiple questions, i.e. items, to capture the target attribute. Dental PROMs (dPROMs) assess different outcomes in comparison to PROMs in other medical fields. These outcomes are called dental PROs (dPROs).3 Orofacial Appearance of dental patient is an example of dPRO. Several dPROMs exist and they differ according to which aspect of the dental patient’s oral health experience they measure and how they measure it. Moreover, different dPROMs for adults and children exist. For example, the Oral Health Impact Profile4 or the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index5 are oral health-related quality of life instruments for adults and the Child Perception Questionnaire6 assesses the same construct in children ages 11–14 years.

For the researcher or the oral health professional interested in measuring dPROs by utilizing dPROMs, few review articles are already available.7,8 Such reviews have limitations when not performed systematically. Therefore, the set of dPROs identified by the systematic review should contain all relevant dPROs. This would improve our foundational oral health knowledge since assessment of the patient’s suffering and the intervention to reduce/eliminate or, ideally, to prevent it are the primary reasons for the existence of dental health professionals. Moreover, a systematic review could also reveal how researchers approached the challenging task to capture patients’ oral health suffering. For example, valuable insight into practical dPRO measurement would be achieved by knowing whether oral health impacts can be captured by simple “yes-no” patient answers, or whether they need to be measured with more complex, gradual response options.

The aim of this systematic review was to identify generic dPROMs for adult patients and their dPROs.

Methods

This review aimed to identify all dPROMs for adult patients with the following characteristics:

Multi-item measures applicable to individual patients were included but without considering patients’ symptoms.

Tools for individual patients were included and, therefore, PROMs for accountable health care entities (i.e., performance measures) were excluded.

Measures that specifically assess oral health impact were included. Measures that focus on oral health’s systemic impacts (e.g., sleep disturbance, depression) were excluded.

Measures that are applicable to a broad range of adult dental patients were included. In contrast to these oral health-generic instruments, those for a specific oral disease (e.g., dry mouth, temporomandibular disorders) or specific patient groups (e.g., edentulous patients) were excluded.

PROM Search

A search strategy was developed for MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA) via the Ovid interface and then translated to Embase (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and PsycINFO (American Psychological Association, Washington DC, USA) via the Ovid interface. A combination of keywords and phrase searching was used to identify dPROMs. The full Ovid Medline search was: (exp Esthetics, Dental/ OR exp Facial Pain/ OR (orofacial adj3 pain).ab,ti. OR (oral adj3 function$).ab,ti. OR (oral health adj3 quality of life).ab,ti.)) AND (exp “Surveys and Questionnaires”/ OR questionnaire$.ab,ti. OR survey$.ab,ti. OR (limitation adj3 scale$).ab, ti. OR (esthetic adj3 scale$).ab, ti. OR Psychometrics/). Authors also added relevant references from personal libraries meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria. The initial literature search was conducted in 2014 and refreshed on December 4, 2017. Results were restricted to human, English language, and adults.

Search results were imported into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) for de-duplication and included references were imported into Mendeley (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) for reference management. Subsequent references were then exported to Microsoft Excel where four reviewers HM, MTJ, SS, and KRS reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion criteria. Only dPROMs that demonstrated evidence for their score reliability and validity were included and only original questionnaires’ publications were assessed.

PROM presentation and analysis

The search identified publications that included dPROMs. A particular dPROM was sometimes combined with other dPROMs within a single questionnaire. For the purpose of this study, we defined a questionnaire as a set of questions or a battery of dPROMs, which can be administered to a patient. Each dPROM is assessing a specific dPRO – the object of measurement, e.g., the dPROM GOHAI5 measures the dPRO OHRQoL. However, the number of dPROMs and dPROs does not need to be identical because a dPRO could be measured by several dPROMs within a single questionnaire. For example, in the questionnaire Subjective Oral Health Status Indicators9 (SOHSI) a broader dPRO was defined as the “functional, social, and psychological impact of oral conditions,” which is measured with three narrower dPROs, namely “Functional limitations”, “Pain and discomfort”, and “Disability and Handicap”. Sometimes these narrower dPROs are called dimensions of a broader dPRO. We assumed a PROM exists, if a numerical score is derived.

The identified questionnaires as well as their dPROs, dPROMs, and dPROMs’ items were characterized in tabular and graphical format. First, an overview of identified questionnaires was provided with information about the original publication. We presented publication year, author names, first author’s country, title of the publication, and name of the questionnaire.

Names of dPROs, their definitions, and their dPROMs were listed afterwards. dPROs were labeled as positive or negative concepts in relation to dental patient’s oral health experience, e.g., Functional Limitation is a negative concept whereas Function was considered a positive concept. Characteristics of patients that were used for questionnaire development, dPROM dimensionality (a psychometric property that is fundamental for the nature and number of attributes being measured), and recall or reference period (the period of time patients were asked to consider in responding to dPROMs) were also extracted. Finally, dPRO names given by the original authors of the questionnaires were analyzed and linked to the four dimensions of the oral health-related quality of life, i.e., Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact.10,11 For dPROs that had two attributes, e.g., Pain and Discomfort, the first attribute was used as the factor for classification. Disability, an interaction between a person’s oral health condition and that individual’s contextual factors, was classified as a part of Psychosocial Impact.

The dPROM’s basic components, i.e., the items, were also characterized. The number of items and impact quality, i.e., how the impact affected the patient over time, were recorded. An impact could have a temporal quality such as a frequency, i.e., how often the impact occurred, or duration, i.e., how long the impact lasted. Duration quality could be further differentiated into length of time for an individual impact episode and length of time since the impact occurred first. Impact could also have a magnitude quality, i.e., intensity of the impact. Therefore, we assessed whether items contained frequency, duration, or intensity as the impact quality or just a simple presence of the impact, a “yes/no” response option.

Furthermore, item’s response options were also characterized. They were differentiated into a “continuous-adjectival” or a “continuous-numerical” category when responses had an order and were represented by adjectives or by a numerical rating scale, respectively. In contrast, a “categorical-adjectival” category was selected when no order was present in the adjectives. The number of response options, their anchors, and anchors’ numerical scores were also extracted as well as items received weights or not for score computation. The source for the questionnaire items was differentiated into patients, experts, or literature.

Results

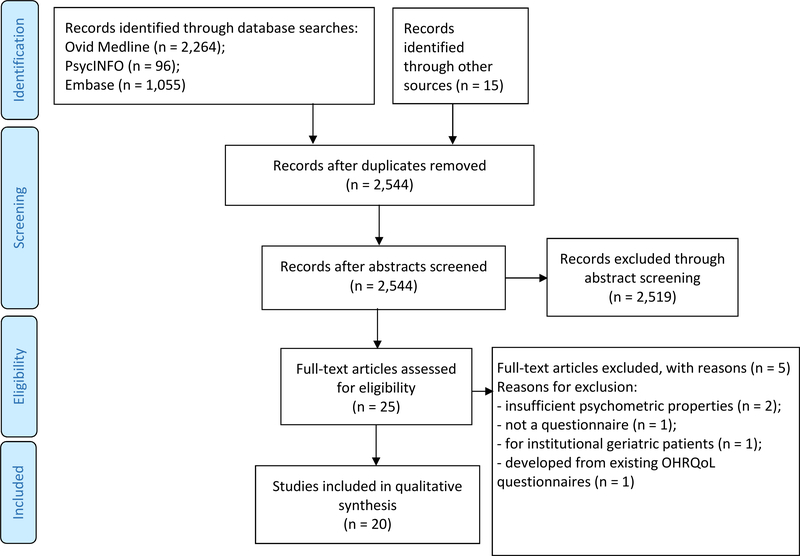

We identified 20 English-language questionnaires (Figure 1) which specifically measured oral health status and were broadly applicable across oral conditions (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of included studies

Table 1.

General information of patient-reported oral health questionnaires

| No. | Questionnaire | Abridged name | Authors | Publication year | Journal or book | First author’s country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rand Dental Health Index12 | Rand DHI | Gooch, Dolan, Bourque | 1989 | Journal of Dental Education | USA |

| 2 | Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index5 | GOHAI | Atchison, Dolan | 1990 | Journal of Dental Education | USA |

| 3 | Jaw Disability Checklist13 | JDC | Dworkin, LeResche | 1992 | Journal of Craniomandibular Disorders: Facial & Oral Pain | USA |

| 4 | Dental Impact Profile14 | DIP | Strauss, Hunt | 1993 | Journal of the American Dental Association | USA |

| 5 | Mandibular Function Impairment Questionnaire15 | MFIQ | Stegenga, de Bont, de Leeuw, Boering | 1993 | Journal of Orofacial Pain | The Netherlands |

| 6 | Oral Health Impact Profile4 | OHIP | Slade, Spencer | 1994 | Community Dental Health | Australia |

| 7 | Subjective Oral Health Status Indicators9 | SOHSI | Locker, Miller | 1994 | Journal of Public Health Dentistry | Canada |

| 8 | Dental Impacts on Daily Living16 | DIDL | Leao, Sheiham | 1996 | Community Dental Health | United Kingdom |

| 9 | Oral Health Quality of Life Inventory17 | OH-QoL | Cornell, Saunders, Paunovich, Frisch | 1997 | Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life, p. 136–149 | USA |

| 10 | Oral Impacts on Daily Performance18 | OIDP | Adulyanon, Sheiham | 1997 | Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life, p.151–160 | Thailand |

| 11 | Oral Health Related Quality of Life-UK19 | OHQoL-UK | McGrath, Bedi | 2001 | Community Dental Health | United Kingdom |

| 12 | Manchester Orofacial Pain Disability Scale20 | MOPDS | Aggarwal, Lunt, Zakrzewska, Macfarlane GJ, Macfarlane TV | 2005 | Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology | United Kingdom |

| 13 | Psychological Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire21 | PIDAQ | Klages, Claus, Wehrbein, Zentner | 2006 | European Journal of Orthodontics | Germany |

| 14 | Jaw Functional Limitation Scale22 | JFLS | Ohrbach, Larsson, List | 2008 | Journal of Orofacial Pain | USA |

| 15 | Chewing Function Questionnaire - Alternative Version23 | Alt-CFQ | Baba, John, Inukai, Aridome, Igarahsi | 2009 | BMC Oral Health | Japan |

| 16 | Modified Symptom Severity Index24 | Mod-SSI | Nixdorf, John, Wall, Fricton, Schiffman | 2010 | Journal of Oral Rehabilitation | USA |

| 17 | Orofacial Esthetic Scale25 | OES | Larsson, John, Nilner, Bondemark, List | 2010 | The International Journal of Prosthodontics | Sweden |

| 18 | Brief Pain Inventory-Facial26 | BPI- F | Lee, Chen, Urban, Hojat, Church, Xie, Farrar | 2010 | Journal of Neurosurgery | USA |

| 19 | New Chewing Function Questionnaire27 | New-CFQ | Persic, Palac, Bunjevac, Celebic | 2013 | Community Dentistry and Oral Croatia Epidemiology | |

| 20 | Craniofacial Pain and Disability Inventory28 | CF-PDI | La Touche, Pardo- Montero, Gil- Martlnez, Paris- Alemany, Angulo- Diaz-Parreno, Suarez-Falcon, Lara-Lara, Fernandez-Carnero | 2014 | Pain Physician | Spain |

These questionnaires were developed in a span of 25 years, between 1989 and 2014 (Table 1). The rate of development of new questionnaires had slowed down with ten developed between 1989 and 2000, eight between 2001 and 2010, and only two after 2010.

Publications’ first authors came from ten countries, with the majority of publications originating from an English speaking country (N=13). Only seven questionnaires were developed in languages other than English but were published in English-language articles. Teams of authors developed the questionnaires. The lowest number of authors was two and the highest was eight. The questionnaires were published in dental journals, medical journals, and books. Only four journals published more than one questionnaire. The Journal of Dental Education, Journal of Orofacial Pain, and Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology each published two questionnaires, while the Community Dental Health journal published three questionnaires. Two questionnaires were introduced in a book.

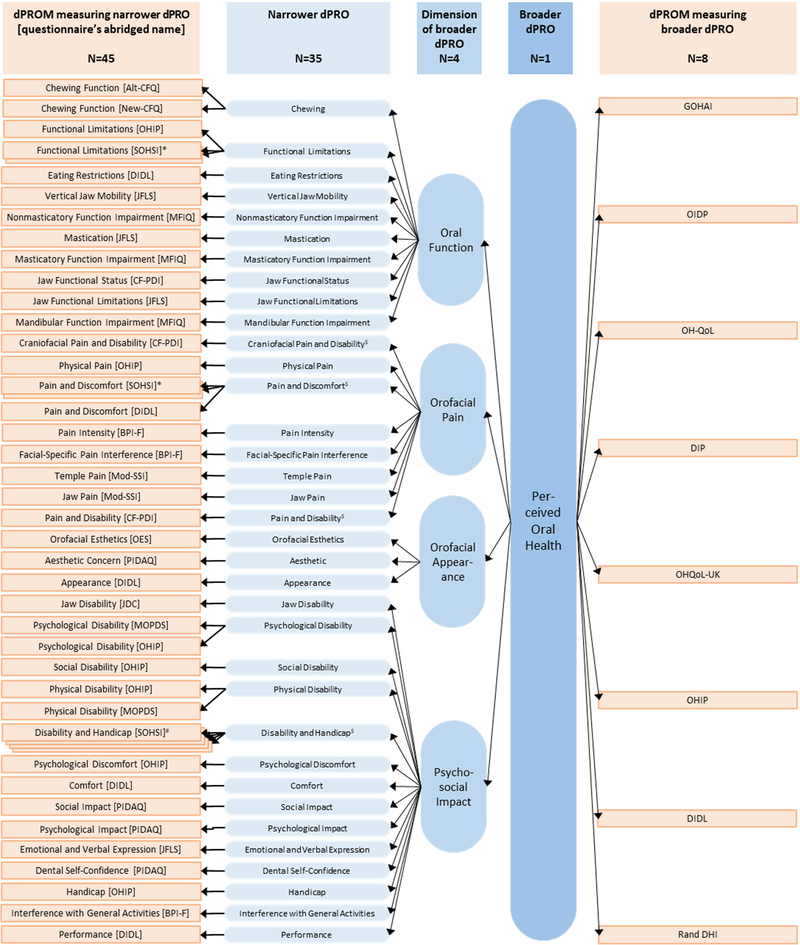

The 20 questionnaires together contained 53 dPROMs. These dPROMs could be differentiated into measures for narrower dPROs (N=45, Figure 2, first column) and for one broad dPRO, representing perceived oral health in general (N=8, Figure 2, fifth column). Sometimes more than one dPROM targeted a particular dPRO, e.g., Functional Limitations were measured in two instruments, the OHIP as well as the SOHSI, resulting in a smaller number of 36 unique dPROs (N=35 narrower unique dPROs, Figure 2, second column, plus N=1 broad unique dPRO, Figure 2, fourth column). The names of 35 narrower unique dPROs suggested they could be grouped into the four dimensions of OHRQoL (Figure 2, third column). Oral Function seemed to be represented by 11, Orofacial Pain also seemed to be represented by seven, Orofacial Appearance seemed to be represented by three, and Psychosocial Impact seemed to be represented by 14 unique dPROs. These four dimensions are the major components of selfperceived oral health in general which itself is a (broad) dPRO. Eight dPROMs targeted this broad dPRO.

Figure 2. Linking dPROMs to their dPROs. dPROMs are represented as rectangles (orange). dPROs are represented as rounded rectangles.

* authors developed two dPROMs for the same dPRO; # authors developed four dPROMs for the same dPRO; $ first of the two attributes was used for linking with broader dPRO

Thirty-six unique dPROs represented 11 (31%) positive and 25 (69%) negative concepts, meaning “more” of a specific positive or negative dPRO was considered a good or bad impact on patients’ oral health experience, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

dPRO characterization

| No | Questionnaire Name | Construct | Dimension | No. of items | Recall Period | GP / DP | Dimensinality Analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Definition | Score | Name | Definition | Score | ||||||

| 1 | Rand Dental Health Index | PsychosocialImpact of Oral ConditionsN | The amount of pain, worry, and concern with social interation (i.e., avoidance of conversation) attributed to problems with teeth or gumsYes | Yes | n/a | n/a | 3 | 3 months | Denatated GP: 16–61 yrs | No | |

| 2 | Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index | Oral Health StatusP | Assessment index for oral oral health in older adult populations | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 12 | 3 months | GP: 65+ yrs | Yes |

| 3 | Jaw Disability Checklist | Jaw DisabilityN | Limitations related to mandibular functioning | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 12 | - | DP: TMD patients | No |

| 4 | Dental Impact Profile | Quality of LifeP | Positive and negative influences on the lives of older adults | Yes | n/a | n/a | 25 | - | GP: 65+ yrs | No | |

| 5 | Mandibular Function Impairment Questionnaire | Mandibular Function IpairmentN | Patient’s appreciation of mandibular function impairment | Yes | Masticatory Function ImpairmentN | Perception of masticatory ability | Yes | 11 | - | DP: TMD patients | Yes |

| 6 | Oral Health Impact Profile | Social Impact of Oral DisordersN | Social impact and oral disorder assessments | Yes | Functional LimitationsN | Loss of function of body parts or systems | Yes | 9 | - | GP: 60+ yrs | No |

| Physical PainN | - | Yes | 9 | ||||||||

| Psychological DiscomfortN | - | Yes | 5 | ||||||||

| Physical DisabilityN | Any limitation in or lack of ability to perform activities of daily living daily living | Yes | 9 | ||||||||

| Psychological DisabilityN | Any limitation in or lack of ability to perform activities of daily living | Yes | 6 | ||||||||

| Social DisabilityN | Any limitation in or lack of ability to perform activities of daily living | Yes | 5 | ||||||||

| HandicapN | Experience of disadvantage | Yes | 6 | ||||||||

| 7 | Subjective Oral Health Status Indicators | - | - | - | Functional LimitationsN | Limitations in the functions performed by body parts or systems | YesII | 6, 3 | - | GP: 18+ yrs | No |

| Pain and DiscomfortN | Experiential aspect of oral conditions in the form of symptoms | YesII | 9, 10 | 4 weeks | |||||||

| Disability and HandicapN | Disability: any difficulty performing activities. Handicap: broader social disadvantage and deprivation occurring as a result of impairment, functional limitation, pain and discomfort, or disability | YesIV | 3, 4, 6, 2 | 1 year | |||||||

| 8 | Dental Impacts on Daily Living | Quality of LifeP | Measures of the impacts of oral health status on the quality of daily living | Yes | ComfortP | Related to complaints such as bleeding gums and food packing | Yes | 7 | - | GP and DP: 35–44 yrs | Yes |

| AppearanceP | Self-image | Yes | 4 | ||||||||

| Pain and DiscomfortN | Physical suffering of discomfort | Yes | 4 | ||||||||

| PerformanceP | Ability to carry out daily function and interact with people | Yes | 15 | ||||||||

| Eating RestrictionsN | Difficulties chewing or biting | Yes | 6 | ||||||||

| 9 | Oral Health Quality of Life | Oral Health Quality of LifeP | Evaluates a person’s subjective wellbeing with respect to her/his oral health and functional status | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 15 | - | DP: 18+ yrs | No |

| 10 | Oral Impacts on Daily Performance | Impacts on Daily PerformancesN | Serious oral impacts on the person’s ability to perform daily activities | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8 | 6 months | GP: 35–44 yrs | No |

| 11 | Oral Health Related Quality of Life-UK | Impact of Oral Health on Quality of LifeN | Individuals rating of the impact or oral health effects on quality of life | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 16 | - | GP: 18+ yrs | Yes |

| 12 | Manchester Orofacial Pain Disability Scale | - | - | - | Physical DisabilityN | - | Yes | 7 | 1 month | GP: 18–65 yrs, DP: not specified | Yes |

| Psychosocial DisabilityN | - | Yes | 19 | ||||||||

| 13 | Psychological Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire | - | - | - | Dental Self confidenceP | Impact of dental aesthetics on the Yes | Yes | 6 | - | GP: 18–30 yrs | Yes |

| Social ImpactN | Potential problems in social situations due to subjective perception of an unfavorable own dental appearance | Yes | 8 | ||||||||

| Psychological ImpactN | Feeling of inferiority and unhappiness when the affected individual compares him/herself with persons with superior dental aesthetics | Yes | 6 | ||||||||

| Aesthetic ConcernN | Disapproval of one’s own dental Yes appearance when confronted with mirror, photographic and/or video images | Yes | 3 | ||||||||

| 14 | Jaw Functional Limitation Scale | Overall Jaw Functional LimitationN | Alterations in jaw functions that individuals with orofacial disorders report as significant | Yes | MasticationP | - | Yes | 6 | 1 month | DP: 18+ yrs | Yes |

| Vertical Jaw MobilityP | - | Yes | 4 | ||||||||

| Emotional and Verbal ExpressionP | - | Yes | 10 | ||||||||

| 15 | Chewing Function Questionnaire-Alternative Version | Chewing FunctionP | Ability to chew | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 20 | - | DP: partially dentate patients | Yes |

| 16 | Modified Symptom Severity Index | - | - | - | Temple PainN | - | Yes | 5 | 1 month | DP: TMD patients | Yes |

| Jaw PainN | - | Yes | 10 | ||||||||

| 17 | Orofacial Esthetic Scale | Orofacial EstheticsP | Direct impacts of impaired orofacial esthetics | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8 | - | DP: not specified | Yes |

| 18 | Brief Pain Inventory-Facial | - | - | - | Pain IntensityN | - | Yes | 4 | 1 week | DP with trigeminal neuralgia or facial pain | Yes |

| Interference With General ActivitiesN | - | Yes | 7 | ||||||||

| Facial-Specific Pain InterferenceN | - | Yes | 7 | ||||||||

| 19 | New Chewing Function Questionnaire | Chewing FunctionP | Patients’ self-assessment of their chewing function | Yes | n/a | n/a | n/a | 10 | - | DP with natural teeth | Yes |

| 20 | Craniofacial Pain and Disability Inventory | Craniofacia l Pain and DisabilityN | Pain, disability, and functional status of the mandibular and craniofacial regions | Yes | Pain and DisabilityN | - | Yes | 14 | - | DP: chronic craniofacial pain patients | Yes |

DP dental patients; GP general population and other non-patient populations;II andIV number of dPROMs for the target dPRO; - not provided by authors; n/a not applicable; P and Npositive and negative concept

Only for eight questionnaires a specific recall period was defined, which varied from one week to one year. One month was mentioned frequently.

These questionnaires were developed most often in subjects from the general population and usually adults from a broad age range were included. Dental patients were used less often and, typically, their age was not specified.

Dimensionality was only investigated in 13 out of 20 questionnaires with some analysis results not matching initial hypotheses about PRO’s dimensionality.

Three to 49 items characterized a single dPRO (Table 3). The median item number per dPROM was seven. Impact quality was measured most often in terms of its intensity (N=17). Frequency of impacts was identified in 10 dPROMs and presence/absence of impacts in 6 dPROMs. Measuring impacts in terms of their duration was rarely done (N=2). In six questionnaires, authors combined two or more impact qualities response concepts.

Table 3.

dPROM item characterization

| Questionnaire | No. of items | Impact concept | Type of judgement | Min. Anchor | Max. Anchor | Response options | Item Source | Sum score calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rand Dental Health Index | 3 | Intensity | Continuous - adjectival | A lot(1) | None (4) | 4 | Experts | Not weighted |

| Intensity | Continuous - adjectival | A lot (1) | None (4) | 4 | ||||

| Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | Most (1) | None (4) | 4 | ||||

| Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index | 12 | Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | Never (0) | Always (5) | 6 | Patients, experts, literature | Not weighted |

| Jaw Disability Checklist | 12 | Presence | Categorical | No (0) | Yes (1) | 2 | - | - |

| Dental Impact Profile | 25 | Presence | Categorical - adjectival | Good effect (1) | No effect (3) | 3 | Patients, experts | - |

| Mandibular Function Impairment Questionnaire | 17 | Intensity | Continuous - numerical | No difficulty (0) | Very difficult or impossible 5 without help (4) | Patients | Not weighted | |

| Oral Health Impact Profile | 49 | Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | None (0) | Very often (4) | 5 | Patients, literature | Weighted |

| Subjective Oral Health Status Indicators | 43 | Presence | Categorical | Yes (0) | No (1) | 2 | Experts, literature | Not weighted |

| Presence | Categorical | No (0) | Yes (1) | 2 | ||||

| Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | All the time (1) | Never (5) | 5 | ||||

| Dental Impacts on Daily Living | 36 | Intensity | Continuous - Likert | Very unsatisfied (−1) | Very satisfied (+1) | 5 | Patients, literature | Weighted |

| Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | Always (−1) | Never (+1) | 5 | ||||

| Presence | Categorical | Yes (−1) | No (+1) | 2 | ||||

| Intensity | Continuous - adjectival | Extremely (−1) | Not at all (+1) | 5 | ||||

| Intensity | Continuous - Likert | Very badly (−1) | Very well (+1) | 5 | ||||

| Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | Every day (−1) | None (+1) | 5 | ||||

| Intensity | Continuous - Likert | Disturbs a lot (−1) | Helps a lot (+1) | 5 | ||||

| Oral Health Quality of Life Inventory | 15 | Intensity | Continuous - Likert | Not at all important (1) | Very important (3) | 3 | Experts, literature | Weighted |

| Intensity | Continuous - Likert | Unhappy (1) | Happy (4) | 4 | ||||

| Oral Impacts on Daily Performance | 8 | Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | Never (0) | Every or nearly every day(5) | 6 | Literature | Not weighted |

| Duration | Continuous - adjectival | 0 days (0) | Over 3 months in total (5) | 6 | ||||

| Intensity | Continuous - numerical | None (0) | Very severe (5) | 6 | ||||

| Oral Health Related Quality of Life-UK | 16 | Intensity | Continuous - Likert | A bad effect of extreme impact (1) | A good effect of no impact (9) | 9 | Patients | Not weighted |

| Manchester Orofacial Pain Disability Scale | 26 | Frequency | Continuous - adjectival | None of the time (0) | On most/ everyday(s) (2) | 3 | Patients | Not weighted |

| Psychological Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire | 23 | Intensity | Continuous - adjectival | Not at all (0) | Very strongly (4) | 5 | Experts, literature | Not weighted |

| Jaw Functional Limitation Scale | 20 | Intensity | Numerical | No limitation (0) | Severe limitation (10) | 11 | Experts, literature | Not weighted |

| Chewing Function Questionnaire – Alternative Version | 20 | Presence | Categorical | Difficult (0) | Easy (1) | 2 | Literature | Not weighted |

| Modified Symptom Severity Index | 15 | Intensity Frequency Duration | Continuous - numerical | No difficulty or never (0) | Worst imaginable or constant (1) | 28 | Patients | Not weighted |

| Orofacial Esthetic Scale | 8 | Intensity | Continuous - numerical | Very dissatisfied (0) | Very satisfied (10) | 11 | Patients | Not weighted |

| Brief Pain Inventory-Facial | 18 | Intensity | Continuous - numerical | Does not interfere (0) | Completely interferes (10) | 11 | Experts, literature | Weighted |

| Intensity | Continuous - numerical | No pain (0) | Pain as bad as you can imagine (10) | 11 | ||||

| New Chewing Function Questionnaire | 10 | Intensity | Continuous - numerical | No problem (0) | Severe problem (4) | 5 | Patients, experts, Literature |

Not weighted |

| Craniofacial Pain and Disability Inventory | 21 | Presence Frequency Intensity | Continuous - numerical | (0) | (3) | 4 | Patients, experts, Literature | - |

In general, the number and nature of response options varied a lot. All identified dPROMs had different response options. Typically, authors preferred to use an adjectival scale as the type of judgement, i.e., they measured impact with an ordinal scale with descriptors for each response option. Often five categories were used, but the number of response options among dPROMs ranged from two to 28. Even when impact quality and type of judgement were the same within a particular dPROM, the applied five response options were not always identical.

The direction of impact also varied. Most items’ minimum anchors represented no impact, but for eight questionnaires, the minimum anchors represented an impact. The minimum and maximum anchors also varied substantially across dPROMs. Two questionnaires contained both directions of impact, i.e., for some questions, the response with a higher score represented more impact, and for other questions, the higher score represented less impact.

As the source of questionnaire items, the literature (N=12), patients (N=11) and experts (N=10) were almost equally involved.

To characterize the construct with an overall score combining items, most authors used a simple summary of item responses. Only four questionnaires had weighted scores.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 20 English-language, multiple-item questionnaires that are applicable to a broad range of adult dental patients. These questionnaires capture 36 different dPROs measured by 53 dPROMs. Thirty-six dPROs represented all major areas of dental patients’ concerns. Fifty-three dPROMs represented the complete set of available measurement tools to assess these concerns. Typically, an individual dPROM contained seven items and the impact intensity was used to capture the patient’s suffering with the five-point adjectival response format. For the majority of dPROMs, all item responses were typically summed to derive a score, i.e., to characterize the impact. Researchers often did not pay enough attention to dimensionality of their dPROMs and often did not specify the recall period. When the recall period was provided, longer periods such as three months to one year were not infrequently selected.

PROs and PROMs for adult dental patients

The individual patient is the center of attention for every oral health care professional. Assuming researchers were interested in creating tools for measuring dental patients’ concerns, the collection of 36 dPROs represents the entire universe of major concerns dental patients can have. The quantity of 36 dPROs is substantial, but these dPROs also overlap substantially. Actually, these dPROs – when their names were analyzed – just captured four basic aspects of patients’ oral health experience, i.e., Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance/Aesthetics, and Psychosocial Impact. These aspects have been identified in a large number of international dental patients and general population subjects with exploratory analyses.10 They were confirmed11 and validated29 as common factors underlying OHRQoL measured with OHIP-49.4 It also demonstrated these four factors underlie other widely used OHRQoL instruments as well.30 Because of their significance and universality, these four overarching themes of patientreported oral health were previously named the “dimensions of OHRQoL”.31

Comparison of methodological approaches for PROM development between instruments for adult dental patients and patients in general

dPROMs are a subgroup of PROMs in general. Although the content of dPROMs is different compared to more general PROMs because specific PROs pertaining to oral health (dPROs) were targeted, general assessment format and methodologies for development of every PROM should be similar and consistent across all medical (including dental) disciplines. For existing differences, “alignment of oral health-related with health-related quality of life assessment”32 was recommended to make dPROMs comparable to ones developed for patients in general. To evaluate the extent to which dPROMs are similar to PROMs for patients in general, we compared their measurement characteristics with those from PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), which is “a set of patient-reported measures for physical, mental, and social health in adults and children.”33 PROMIS was created in 2004 to develop standardized measures to capture essential patient-reported health outcomes, such as pain, fatigue, physical functioning, and other dimensions of general health.

State-of-the-art approaches in PROM development require first to define what is to be measured. A similar emphasis is placed on dimensionality, i.e., a psychometric property that refers to the number and nature of underlying attributes reflected in the questionnaire’s items.34

With regard to the definition of identified dPROs, the questionnaire authors approached the definition of targeted constructs mostly intuitively without providing formal definition of dPROs in their original publications. In most cases, this approach seemed to be sufficient because for many dPROs, the definition could be easily extracted from the dPRO’s name. For example, a questionnaire targeting orofacial pain impact does not need an elaborate construct definition because a general pain definition exists35 and “orofacial” is just the descriptor of location where this pain occurs.

As stated before, dimensionality is fundamental to PROM development36 and this systematic review identified limitations for many dPROMs. In several cases, computation of summary score was not supported by dimensionality analysis. Consequently, it is not known how well dPROMs characterize dPROs, i.e., their validity is questionable.

For every PROM, patients should be the main source of items because they intend to capture patients’ concerns. While contemporary approaches for PROM development such as PROMIS recommend involvement of patients in focus groups, cognitive interviews, and similar techniques,33 only about half of identified questionnaires used patients to derive the items. Instead, authors often selected items from the literature or utilized experts’ opinions. Although using experts and literature is methodologically inferior to direct involvement of patients, it can be assumed that an expert opinion reflects indirectly what matters to patients. However, a combination of patients and experts is certainly the best approach.

The median number of items per dPROM was seven. This is similar to PROMIS questionnaires, which typically have between four to twelve items.37 Sometimes researchers introduced first a long PROM and shortened versions were developed later to decrease respondent burden. For the most widely used dPROM, the OHIP, a similar development was observed. The original OHIP 49-item version4 was later accompanied by shorter OHIP versions, such as the 14-item38 or the 5-item version39. Only one other questionnaire identified in this review, the JFLS,22 also had a short-form.22

dPROMs typically captured intensity or frequency quality of oral health impact with a five-step adjectival scale. This is in line with PROMIS instruments.

The term “patient-reported outcome measure” implies that individuals diagnosed with a disease are the major target for PROMs. Typically, these patients receive treatment and the health condition improves. Therefore, to capture rapidly changing health, PROMs need to have a short recall or reference period. PROMIS measures typically have a 7-day recall period. Only one questionnaire in our review had a one-week recall period. For OHIP, such a short recall period was developed later40 to make this instrument more suitable for clinical research. Twelve out of 20 questionnaires in our review did not have a defined recall period. Therefore, most of these instruments would be challenged to measure rapidly changing oral health due to dental interventions.

Comparison with the literature

A systematic review of dPROs and dPROMs for adult patients has not been performed yet, but similar reviews are already available for medical patients, e.g., for venous ulceration,41 cancer cachexia,42 and inflammatory bowel disease.43 Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaires, a widely used type of PROM, were reviewed most often for the three above- mentioned and other diseases. This is in line with our review for dental patients. Nearly half of our identified questionnaires intend to measure the dPRO OHRQoL. In contrast to our review, previously mentioned reviews mainly focused on the assessment of identified PROMs’ psychometric properties such as reliability and validity. Our review characterized in detail dPROs, dPROMs, and the questionnaire items. Nevertheless, score reliability as well as validity were used as inclusion criteria for our systematic review. Only questionnaires with these two basic psychometric properties were considered.

Other systematic reviews for dPROMs exist, but they focused on specific diseases, e.g., head and neck cancer44 or burning mouth syndrome.45 Several narrative reviews are also available for PROMs for dental patients. Most of these reviews targeted OHRQoL.7,8

Scope, advantages, and limitations of this systematic review

As mentioned above, our review’s scope is different compared to previous reviews and we discuss essential PROM features such as type, format/length, and target population in more detail.

The type of PROM: as previously stated, PROMs can be divided into three broad categories, measuring (i) status of patient’s health condition, (ii) health behaviors, and (iii) experience with health care. We considered the characterization of patient’s self-assessed oral health condition the most important category in dental medicine and, therefore, we only targeted this type of PROMs. Because the vast majority of scientific journals are published in English, we assumed the majority of dPROMs would also be published in this language. We may have missed non-English instruments but believe, if such instruments would have gained wider acceptance, findings from instrument application studies would have been subsequently published in journals included in our electronic search and therefore we should have identified most of them.

PROM’s format and length: we targeted only multi-item PROMs. They can be differentiated from single-item PROMs, e.g., a global overall assessment of person’s oral or general health status or a single global oral health rating.46 We did not include single-item PROMs in this systematic review because, while they have advantages in terms of reduced patient burden, they are typically considered inferior compared to multi-item PROMs, in particular when broader constructs are measured.47 We considered oral health as such a broader construct.

PROM’s target populations: our focus was the measurement of patients’ self-perceived oral health condition. For assessment of specific psychosocial impact of oral conditions, e.g., oral conditions affecting sleep quality or depression/sadness, disease-specific PROMs exist, e.g., a PROMIS measure for sleep quality and a PROMIS measure for depression.37 We were only interested in capturing direct stomatognathic system-specific oral health experiences that are applicable to a broad range of adult dental patients, i.e., oral health-generic instruments. dPROMs that were developed to assess a particular oral disease/condition impact, such as hypersensitive teeth,48 or certain treatments, such as implant-supported dentures,49 were not included in our review.

Adults and children are two populations for PROM application. We focused on adults only because of the greater size of this population.

Finally, we would like to emphasize that some dPROMs received further methodological studies in other populations or investigations of their dimensionality and recall periods. We did not track resulting dPROM modifications nor included them in this systematic review. While several modifications were suggested, e.g., the use of a more practical 5-point response format for the Orofacial Esthetics Scale,50 such modification, except for the use of unweighted (simple) summary scores, were rarely adopted by the international research community. We also would like to point out that investigations of methodological factors such as item-order effects,51 instrument order effects,52 recall periods,40 memory effects,53 response shift,54 or countable impacts55 that were mainly performed for the OHIP questionnaire contribute to better understanding of dPROMs psychometric properties in general.

Conclusion

The 36 dPROs represent all major aspects of dental patients’ oral health experience; however, they can be summarized into four simple and clinically intuitive dPRO groups - Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact.

The 53 dPROMs measuring the 36 dPROs represent currently available multiple items tools for measurement of self-assessed dental patients’ suffering with oral health-generic instruments. While some dPROMs have received recommendations for modifications and application of these dPROMs in specific settings has contributed to a better understanding of scores’ psychometric properties, common limitations of many of these dPROMs continue to be their unknown dimensionality and missing recall period. Unknown dimensionality challenges validity of dPROMs and missing recall period challenges clinical utility of dPROMs, in particular, the assessment of dental interventions’ treatment effects.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Kathleen M. Patka, Executive Office and Administrative Specialist and Ms. Shelby LaFreniere, Principal Office and Administrative Specialist, Division of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, for proofreading the manuscript.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, United States, under Award Number R01DE022331.

List of Abbreviations:

- PRO

Patient-Reported Outcome

- dPRO

Dental Patient-Reported Outcome

- PROM

Patient-Reported Outcome Measure

- dPROM

Dental Patient-Reported Outcome Measure

- OHRQoL

Oral Health-Related Quality of Life

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Footnotes

Declarations of interest:

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gwaltney CJ. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in dental clinical trials and product development: introduction to scientific and regulatory considerations. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10(2):86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John MT. Health outcomes reported by dental patients. J Evid Based Dent Pract; 2018, 10.1016/j.jebdp.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11(1):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. J Dent Educ. 1990;54(11):680–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2002;81(7):459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennadi D, Reddy CVK. Oral health related quality of life. ISPCD. 2013;3(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen PF. Assessment of oral health related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locker D, Miller Y. Evaluation of subjective oral health status indicators. J Public Health Dent. 1994;54(3):167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John MT, Reissmann DR, Feuerstahler L, et al. Exploratory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(9):635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.John MT, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(9):644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gooch BF, Dolan TA, Bourque LB. Correlates of self-reported dental health status upon enrollment in the Rand Health Insurance Experiment. J Dent Educ 1989;53(11):629–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6(4):301–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss RP, Hunt RJ. Understanding the value of teeth to older adults: influences on the quality of life. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124(1):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stegenga B, de Bont LG, de Leeuw R, Boering G. Assessment of mandibular function impairment associated with temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis and internal derangement. J Orofac Pain. 1993;7(2):183–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leao A, Sheiham A. The development of a socio-dental measure of dental impacts on daily living. Community Dent Health. 1996;13(1):22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornell JE, Saunders MJ, Paunovich ED, Frisch MB. Oral health quality of life inventory (OH-QoL) In: Slade GD, ed. Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina; 1997:136–149. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adulyanon S, Sheiham A. Oral impacts on daily performances In: Slade GD, ed. Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina; 1997:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGrath C, Bedi R. An evaluation of a new measure of oral health related quality of life--OHQoL-UK(W). Community Dent Health. 2001;18(3):138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal VR, Lunt M, Zakrzewska JM, Macfarlane GJ, Macfarlane TV. Development and validation of the Manchester orofacial pain disability scale. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(2):141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klages U, Claus N, Wehrbein H, Zentner A. Development of a questionnaire for assessment of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics in young adults. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28(2):103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohrbach R, Larsson P, List T. The jaw functional limitation scale: development, reliability, and validity of 8-item and 20-item versions. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22(3):219–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baba K, John MT, Inukai M, Aridome K, Igarahsi Y. Validating an alternate version of the chewing function questionnaire in partially dentate patients. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nixdorf DR, John MT, Wall MM, Fricton JR, Schiffman EL. Psychometric properties of the modified Symptom Severity Index (SSI). J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(1):11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsson P, John MT, Nilner K, Bondemark L, List T. Development of an Orofacial Esthetic Scale in prosthodontic patients. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23(3):249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JY, Chen HI, Urban C, et al. Development of and psychometric testing for the Brief Pain Inventory-Facial in patients with facial pain syndromes. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(3):516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peršić S, Palac A, Bunjevac T, Celebić A. Development of a new chewing function questionnaire for assessment of a self-perceived chewing function. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(6):565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Touche R, Pardo-Montero J, Gil-Martínez A, et al. Craniofacial pain and disability inventory (CF-PDI): development and psychometric validation of a new questionnaire. Pain Physician. 2014;17(1):95–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John MT, Rener-Sitar K, Baba K, et al. Patterns of impaired oral health-related quality of life dimensions. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43(7):519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John MT, Reissmann DR, Čelebić A, et al. Integration of oral health-related quality of life instruments. J Dent. 2016;53:38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.John MT, Hujoel P, Miglioretti DL, LeResche L, Koepsell TD, Micheelis W. Dimensions of oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2004;83(12):956–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reissmann DR. Alignment of oral health-related with health-related quality of life assessment. J Prosthodont Res. 2016;60(2):69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wikipedia contributors. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patient-Reported_Outcomes_Measurement_Information_System/; 2017. Accessed 17 September 2017.

- 34.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pain terms: a list of definitions and notes on usage. Recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain. 1979;6(3):249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(5):S22–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Northwestern University. List of adult measures: available PROMIS measures for adults. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/list-ofadult-measures/; Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 38.Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(4):284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naik A, John MT, Kohli N, Self K, Flynn P. Validation of the English-language version of 5-item Oral Health Impact Profile. J Prosthodont Res. 2016;60(2):85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waller N, John MT, Feuerstahler L, et al. A 7-day recall period for a clinical application of the oral health impact profile questionnaire. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20(1):91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palfreyman SJ, Tod AM, Brazier JE, Michaels JA. A systematic review of health-related quality of life instruments used for people with venous ulcers: An assessment of their suitability and psychometric properties. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19–20):2673–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wheelwright S, Darlington AS, Hopkinson JB, Fitzsimmons D, White A, Johnson CD. A systematic review of health-related quality of life instruments in patients with cancer cachexia. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2625–2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Appelbaum MI. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Functional status and patient worries and concerns. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34(9):1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ojo B, Genden EM, Teng MS, Milbury K, Misiukiewicz KJ, Badr H. A systematic review of head and neck cancer quality of life assessment instruments. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(10):923–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ni Riordain R, McCreary C. Patient-reported outcome measures in burning mouth syndrome - a review of the literature. Oral Dis. 2013;19(3):230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomson WM, Mejia GC, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. Construct Validity of Locker’s Global Oral Health Item. J Dent Res. 2012;91(11):1038–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sloan JA, Aaronson N, Cappelleri JC, Fairclough DL, Varricchio C. Assessing the Clinical Significance of Single Items Relative to Summated Scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(5):479–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boiko OV, Baker SR, Gibson BJ, Locker D, Sufi F, Barlow AP, Robinson PG. Construction and validation of the quality of life measure for dentine hypersensitivity (DHEQ). J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(11):973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preciado A, Del Río J, Lynch CD, Castillo-Oyagüe R. A new, short, specific questionnaire (QoLIP-10) for evaluating the oral health-related quality of life of implant-retained overdenture and hybrid prosthesis wearers. J Dent. 2013;41(9):753–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Persic S, Milardovic S, Mehulic K, Celebic A. Psychometric properties of the Croatian version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale and suggestions for modification. Int J Prosthodont. 2011;24(6):523–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kieffer JM, Hoogstraten J. Item-order effects in the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP). Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116(3):245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kieffer JM, Verrips GH, Hoogstraten J. Instrument-order effects: using the Oral Health Impact Profile 49 and the Short Form 12. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(1):69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.John MT, Reissmann DR, Schierz O, Allen F. No significant retest effects in oral healthrelated quality of life assessment using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66(3):135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reissmann DR, Erler A, Hirsch C, Sierwald I, Machuca C, Schierz O. Bias in retrospective assessment of perceived dental treatment effects when using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(3):775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reissmann DR, Sierwald I, Heydecke G, John MT. Interpreting one oral health impact profile point. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]