Abstract

Purpose

Radiation-induced sarcoma (RIS) is a rare but serious event. Its occurrence has been discussed during the implementation of new radiation techniques and justified appropriate radioprotection requirements. New approaches targeting intrinsic radio-sensitivity have been described, such as radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis (RILA) able to predict late radio-induced toxicities. We studied the role of RILA as a predisposing factor for RIS as a late adverse event following radiation therapy (RT).

Patients and methods

In this prospective biological study, a total of 120 patients diagnosed with RIS were matched with 240 control patients with cancer other than sarcoma, for age, sex, primary tumor location and delay after radiation. RILA was prospectively assessed from blood samples using flow cytometry.

Results

Three hundred and forty-seven patients were analyzed (118 RIS patients and 229 matched control patients). A majority (74%) were initially treated by RT for breast cancer. The mean RT dose was comparable with a similar mean (± standard deviation) for RIS (53.7 ± 16.0 Gy) and control patients (57.1 ± 15.1 Gy) (p = .053). Median RILA values were significantly lower in RIS than in control patients with respectively 18.5% [5.5–55.7] and 22.3% [3.8–52.2] (p = .0008). Thus, patients with a RILA >21.3% are less likely to develop RIS (p < .0001, OR: 0.358, 95%CI [0.221–0.599].

Conclusion

RILA is a promising indicator to predict an individual risk of developing RIS. Our results should be followed up and compared with molecular and genomic testing in order to better identify patients at risk. A dedicated strategy could be developed to define and inform high-risk patients who require a specific approach for primary tumor treatment and long term follow-up.

Keywords: Radio-induced sarcoma, Predictive biomarker, Apoptosis, Lymphocyte

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Currently, more than half of patients with cancer undergo radiation therapy (RT) as part of their treatment strategy. Each patient presents an individual level of radiosensitivity. About 5–10% of patients receiving RT develop late severe toxicity (fibrosis, secondary cancer…).

Radiation-induced sarcoma (RIS) is a rare but serious adverse event following RT, and overall survival at 5 years for patients developing such a sarcoma is estimated between 10% and 36%, depending on tumor stage at the moment of diagnosis. The development of a biomarker which may predict the risk to develop a RIS will help clinicians to adapt patient treatment and follow up.

Recently, a prospective multicenter French trial including >500 breast-cancer patients suggested that RILA can predict the risk of radio-induced breast fibrosis.

Because RIS is a serious late radio-induced toxicity, the aim of the current study is to assess RILA as a predictive factor for the development of RIS.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge this is the first translational clinical trial specifically designed to highlight a biomarker which may help to predict risk to develop a RIS. This national multicentric study allowed to analyze a large cohort of patients: 118 RIS patients and 229 matched control patients previously treated by RT free from RIS.

Implications of all available evidence

Our study showed that RILA biomarker was significantly correlated with a risk of RIS development. After validation of these results by an ongoing study in a second cohort of patients, this biomarker will provide clinicians a tool to personalize RT prescription in fragile or at risk populations and to personalize patient at risk follow up, allowing treatment at an earlier stage and improvement of disease prognosis.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

More than half of patients with cancer undergo radiation therapy (RT) as part of their treatment strategy [1]. In many cases, RT prevents recurrence in the main tumor site and improves overall survival. Consequently, long term radio-induced toxicity is becoming an increasingly important issue. Sarcoma is a rare but serious adverse event following radiation exposure, and overall survival at 5 years of patients developing sarcoma is estimated between 10 and 36% [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]]. The defining criteria for radiation-induced sarcoma (RIS) have changed over time [[8], [9], [10]]. The most recent version has suggested the following criteria: [1] patient should have received RT; [2] the neoplasm occurred within the radiation volume; [3] a latency of several years; [4] microscopic proof of sarcoma. This definition excludes patients with cancer syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni or Rothmund-Thomson [11]. The ten-year cumulative risk of developing RIS is described as <1% [5,6,[12], [13], [14]]. Radiation-induced sarcomas are generally observed 6 to 20 years after RT [[14], [15], [16], [17]] with various histopathological types, such as angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma. The majority of published studies about post-radiation sarcomas include a limited number of patients, and most frequently report angiosarcoma post breast cancer management [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]].

The risk-benefit ratio for RT is balanced between tumor control and injury to normal tissue. Widely accepted international guidelines such as QUANTEC recommend dose constraints for each at-risk organ in order to limit radio-induced toxicity [24]. There is wide variation between patients in normal-tissue tolerance and therefore, in the frequency and intensity of radio-induced late toxicity. About 5–10% of patients receiving radiotherapy develop severe late toxicity (RIS included) [25,26]. Twenty years ago, a predictive assay based on radio-induced lymphocyte apoptosis (RILA) quantification was developed [27,28]. This assay evaluated the quantity of peripheral blood lymphocytes dying by apoptosis after ionizing radiation exposure (8Gy). In 2005, a first prospective study of 400 patients treated with curative-intent radiotherapy was published [29] and highlighted the significant correlation between CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis and grade 2 or 3 radiation-induced late toxicity. Overall, RILA values >16% were significantly associated with a very low risk of grade ≥ 2 late toxicity. Conversely, RILA values below 10% were strongly associated with severe late complications. Foro et al. [30] confirmed the significant correlation between radio-induced apoptosis of CD4+ T lymphocytes and genitourinary toxicity in 214 patients with prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. Subsequent trials have confirmed these data for various tumor locations (breast, prostate, head and neck) [31,32]. More recently, a prospective multicenter French trial including >500 breast-cancer patients suggested that RILA can predict the risk of radio-induced breast fibrosis [33].

Because RIS is a serious late radio-induced toxicity, the aim of the current study is to assess RILA as a predictive factor for the development of RIS.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Methods

We designed a prospective study scheduled to include 120 patients with RIS who were matched for potential confounding factors with 240 control patients without RIS. For each RIS patient, two control patients were included. The matching criteria were: sex, age during RT (± 5 years), breast or chest RT for patients with breast cancer.

A sample of 120 subjects from the case population and 240 subjects from the control population produce a two-sided 95.0% confidence interval with a precision comprised between 5 and 6% assuming a sample AUC between 0.70 and 0.80.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

Fifteen French centers, participating in the French Sarcoma Group (GSF-GETO), included patients in this prospective translational study. This trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov under the number NCT01504360. GSF-GETO selected patients alive with RIS from a national register containing all individuals diagnosed with sarcoma and followed by a hospital participating in this trial. The initial sarcoma diagnosis of RIS patients was systematically reviewed by expert pathologists in France.

The eligibility criteria for control patients were: no soft tissue sarcoma; >5 years complete remission following RT for cancer, adults aged over 18 years for the treatment of primary tumor. Controls were matched to RIS patients according to sex, age at initial radiotherapy (± 5 years) and for initial breast cancer, control patients treated initially for breast cancer had to have undergone the same type of surgery (mastectomy versus lumpectomy) as the associated RIS patient. Inclusion of control patients was performed during a standard follow-up consultation.

Specific eligibility criteria for RIS patients included: histologically proven soft tissue sarcoma developed in the previously treated area, adults aged over 18 years for the treatment of the primary tumor; primary tumor other than sarcoma as the initial cancer treated by RT. Inclusion of RIS patients was performed at the moment of RIS diagnosis or during a follow-up consultation.

Bone sarcomas were exclusion criteria for all patients. Patients were not receiving chemotherapy at the time of blood sampling in the present study, to avoid chemotherapy effect of on RILA results.

2.3. Inclusions and shipping procedures for blood samples

Before inclusion, all patients were given by clinicians and signed a written informed consent during a follow-up consultation.

For each included patient, one blood sample was collected in a 5 ml heparinized tube. Blood samples were shipped the same day for RILA analysis (Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine, Nancy, France) at room temperature using a specialized transporter (Transporteo, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France).

2.4. Radio-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis (RILA) analysis

RILA measurement was performed in the Department of Biopathology (Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine, Nancy, France) after validation of the correlation with results obtained by the laboratory of Montpellier (IRCM, Inserm U1194, France), the reference laboratory for this assay [34]. The measurement protocol has been previously described [29].

Briefly, blood was diluted 1:10 in RPMI 1640 medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum, irradiated at 0 Gy (sham samples) or 8 Gy using a linear accelerator (photons, 6 MeV, Clinac iX, Varian Medical Systems). After 48 h of incubation, cells were labeled using FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson, Rungis, France), red blood cells were lysed, and DNA was stained with propidium iodide. Samples were measured in duplicate using a flow cytometer (FACScalibur, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and data analysis was performed using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Apoptotic CD8 T-lymphocytes were defined as positively-selected FITC-labeled cells (FL2 >101) presenting a DNA content lower than 1n.

Each apoptosis evaluation was carried out in triplicate. The RILA measurements were expressed by the delta of RILA percentages after 8Gy minus RILA in non-irradiated controls.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage, and compared using the Chi2 (using quartile and tertile analysis) or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables are described as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and/or median (range) and compared using the Student t or non-parametric Mann Whitney test in case of non-normal distribution. Normality was evaluated using Shapiro-Wilk normality test. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) modeling RIS occurrence according to RILA percentage was determined with a 95% confidence interval, using logistic regression. The RILA concentration with the highest Youden index was considered as the optimal cut-off value for the prediction of RIS. A sub-group analysis has been performed in patients with a primary breast cancer, which was the most frequent localization to develop a RIS. However, analysis was a secondary objective and exclusively descriptive. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All tests were two sided and p-values <.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Trial Profile

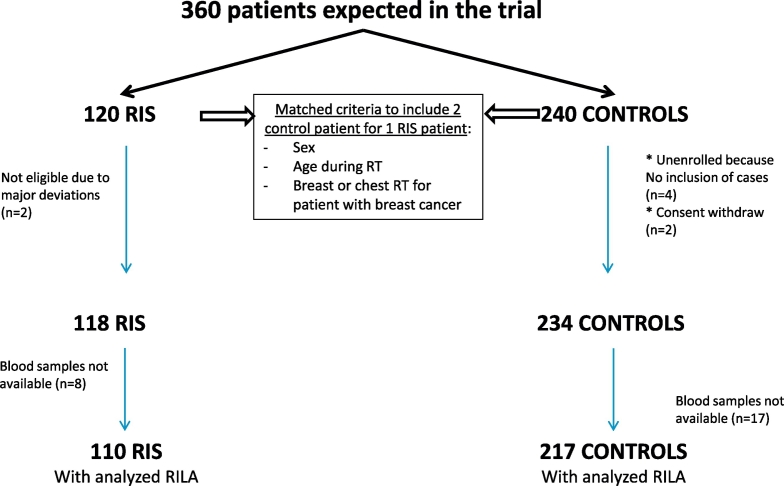

From November 2011 to July 2016, 120 RIS patients and 236 control patients were enrolled in this study. At baseline, two RIS patients were excluded for major protocol violation (as well as their corresponding four matched controls), two control patients withdrew consent and blood samples were not technically available for 25 patients (8 RIS patients and 17 control patients). The flowchart of the study population is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the SARI (SArcoma Radio-Induced) study.

RIS: Radiation-induced sarcoma, RILA: radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis.

3.2. Patient, disease and treatment characteristics

Study population characteristics are presented in Table 1. More than 80% of patients enrolled in the study were women, and >75% presented a primary breast tumor. The median age at initial RT was 53 years (range 20.6–91 years for RIS patients and 20–89 years for controls). As per the study design, patients and controls were matched for sex and age, and thus, no difference was observed between groups. No statistical differences were observed between RIS and controls for total RT with 53.7 ± 16 Gy and 57.1 ± 15.1 Gy, respectively (p = .0535). The median total dose of RT was 50 Gy (range 8–150), including 1.8 to 3.9% brachytherapy as part of the treatment for RIS and control patients, respectively. Overall, 37.3% of RIS patients and 43.3% of control patients received chemotherapy delivered in an adjuvant setting after initial RT (p = .294), while 47.1% of RIS patients and 54.8% of control patients received hormone therapy for their primary cancer (p = .224). For whole population, the median year of initial cancer diagnosis was 2006 [1966–2012]. Concerning RIS patients, the median time between primary tumor treatment by radiotherapy and sarcoma diagnosis was 10.1 [1.8–46.0] years, and the median delay between RIS diagnosis and inclusion in this trial was 11.3 [0.2–352.8] months.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the time of first treatment by radiation therapy, and time to development of radiation-induced sarcoma.

| RISb |

Controls |

p-value (test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 110 | N = 217 | ||

| Age at the time of RTa | 0.471 (Student) | ||

| median [min-max] | 53.0 [20.6–91.0] | 53.0 [20.0–89.0] | |

| Missing data | 22 | 4 | |

| Sex | 0.490 (Chi2) | ||

| Male | 20 (18.2%) | 33 (15.2%) | |

| Female | 90 (81.8%) | 184 (84.8%) | |

| Primary tumor localization | 0.692 (Fisher exact) | ||

| Breast | 87 (75.9%) | 163 (75.1%) | |

| Head and Neck | 8 (7.4%) | 20 (9.2%) | |

| Pelvis | 7 (6.5%) | 19 (8.8%) | |

| Other | 13 (12%) | 15 (6.9%) | |

| RIS histological types | |

|---|---|

| Angiosarcoma | 66 (60%) |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 10 (9.1%) |

| Pleiomorphic sarcoma | 9 (8.2% |

| Uncertain differentiation sarcoma | 6 (5.5%) |

| Liposarcoma | 4 (3.6%) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 4 (3.6%) |

| Others | 10 (9.1%) |

| RTa total dose | 0.0535 (Mann-Whitney) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (standard deviation) | 53.7 (16.0) | 57.1 (15.1) | |

| Missing data | 27 | 8 | |

| RTa Fraction quantity | 0.145 (Mann-Whitney) | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 23.1 (6.3) | 24.0 (5.5) | |

| Missing data | 76 | 67 | |

| Brachytherapy | 2 (1.8%) | 8 (3.7%) | 0.5046 (Fisher exact) |

| Chemotherapy | 41 (37.3%) | 94 (43.3%) | 0.294 (Chi2) |

| Hormone therapy | 52 (47.1%) | 119 (54.8%) | 0.224 (Chi2) |

| Surgery | 96 (88.9%) | 188 (86.6%) | 0.564 (Chi2) |

| Time from primary tumor to RIS diagnosis (years) | |||

| median [min-max] | 10.1 [1.8–46.0] | ||

Radiation therapy.

Radio-induced sarcoma

3.3. Analysis of differences in RILA for RIS and control patients

Median RILA was 18.5% (range 5.5–55.7%) and 22.3% (range 3.8–52.2%) for RIS and control patients, respectively, (p = .0008, Table 2). This difference remained significant after analysis in quartiles (p = .002) or in tertiles using the limits described in two previous published studies (p = .0292 with limits of 16 and 24%; p = .0004 with limits of 12 and 20%) [29,33]. Using a quartile analysis, the proportion of RILA lesser than 12% was 18.2% for RIS patients versus 10.6% for control patients. Additionally, the proportion of RILA higher than 20% was 38.2% for RIS patients versus 61.3% for control patients.

Table 2.

RILA analysis in patients with RIS and controls.

| RISc |

Controls |

p-value (test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 110 | N = 217 | ||

| RILA (%)a | |||

| mean (SDb) | 19.63 (9.1) | 22.44 (8.4) | 0.0008 (Mann-Whitney) |

| median [min-max] | 18.5 [5.5–55.7] | 22.3 [3.8–52.2] | |

| Quartile analysis | 0.002 (Chi2) | ||

| <15.4 | 35 (31.8%) | 44 (20.3%) | |

| [15.4–21.1[ | 36 (32.7%) | 47 (21.7%) | |

| [21.1–26.3[ | 19 (17.3%) | 64 (29.5%) | |

| ≥26.3 | 20 (18.2%) | 62 (28.6%) | |

| Tertile analysis according to (Ozsahin et al. 2005) | 0.0292 (Chi2) | ||

| <16 | 38 (34.55%) | 48 (22.12%) | |

| [16–24] | 45 (40.91%) | 92 (42.40%) | |

| >24 | 27 (24.55%) | 77 (35.48%) | |

| Tertile analysis according to (Azria et al. 2015) | 0.0004 (Chi2) | ||

| <12 | 20 (18.18%) | 23 (10.60%) | |

| [12−20] | 48 (43.64%) | 61 (28.11%) | |

| >20 | 42 (38.18%) | 133 (61.29%) | |

Radiation-Induced CD8 T-Lymphocyte Apoptosis.

Standard Deviation.

Radio-Induced Sarcoma.

3.4. Analysis of differences in RILA for RIS and control patients with initial breast cancer

In a subgroup analysis of patients initially treated for breast cancer, median RILA was significantly different for RIS and control patients, at 18.4% (5.5 to 55.7%) and 22.3% (3.8 to 52.2%), respectively, (p = .0015; Table 3). This difference remained significant after analysis in quartiles (p = .0087) or in tertiles using the cut-offs 12% and 20% as described by Azria et al. (p = .0017), though the difference was not significant using cut-offs of 16% and 24% as described by Ozsahin et al. (p = .0564) [29,33].

Table 3.

RILA analysis for RIS and Control patients with a breast cancer as primary disease.

| RISc |

Controls |

p-value (test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 82 | N = 163 | ||

| RILA (%)a | |||

| mean (SD)b | 19.1 (9.2) | 22.36 (8.6) | 0.0015 (Mann-Whitney) |

| median [min-max] | 18.4 [5.5–55.7] | 22.3 [3.8–52.2] | |

| Quartile analysis | 0.0087 (Chi2) | ||

| <15.1 | 30 (36.6%) | 34 (20.9%) | |

| [15.1–20.7[ | 24 (29.3%) | 37 (22.7%) | |

| [20.7–26.2[ | 14 (17.1%) | 46 (28.2%) | |

| ≥ 26.2 | 14 (17.1%) | 46 (28.2%) | |

| Tertile analysis according to (Ozsahin et al. 2005) | |||

| <16 | 30 (36.59%) | 38 (23.46%) | 0.0564 (Chi2) |

| [16–24] | 33 (40.24%) | 69 (42.59%) | |

| >24 | 19 (23.17%) | 56 (33.95%) | |

| Tertile analysis according to (Azria et al. 2015) | |||

| <12 | 17 (20.73%) | 17 (10.43%) | 0.0017 (Chi2) |

| [12–20] | 35 (42.68%) | 48 (29.45%) | |

| >20 | 30 (36.59%) | 99 (60.12%) | |

Radiation-Induced CD8 T-Lymphocyte Apoptosis.

Standard Deviation.

Radio-Induced Sarcoma.

3.5. Impact of other parameters on RILA

There was no significant relation between initial chemotherapy (to treat primary tumor) in either the RILA group or the control group RILA (p = .709 for RIS patients and p = .256 for control patients, p = .35 overall) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relationship between clinical parameters and treatment other than RT and RILA in RIS and control patients.

| Whole population |

RISe |

Controls |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | RILA (%) mean (SD)a, b | n | RILA (%) mean (SD)a, b | n | RILA (%) mean (SD)a, b | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 135 | 20.7 (7.6) | 41 | 19.1 (7.8) | 94 | 21.4 (7.4) |

| No | 192 | 22.1 (9.5) | 69 | 20.0 (9.9) | 123 | 23.2 (9.1) |

| P value (test) | 0.353 (MWc) | 0.853 (MWc) | 0.218 (MWc) | |||

| Hormonotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 171 | 20.8 (8.5) | 52 | 19.4 (9.1) | 119 | 21.4 (8.3) |

| No | 155 | 22.2 (9.0) | 57 | 19.8 (9.3) | 98 | 23.7 (8.4) |

| P value (test) | 0.104 (MWc) | 0.968 (MWc) | 0.018 (MWc) | |||

| Age during RTd | ||||||

| < 53 years old | 143 | 21.2 (7.3) | 41 | 18.7 (6.7) | 102 | 22.2 (7.3) |

| ≥ 53 years old | 158 | 21.8 (10.2) | 47 | 29.5 (11.9) | 111 | 22.8 (9.3) |

| p value (test) | 0.893 (MWc) | 0.398 (MWc) | 0.760 (MWc) | |||

| Delay between RTd and sarcoma diagnosis | ||||||

| < 10 years | NA | NA | 53 | 19.9 (9.6) | NA | NA |

| ≥ 10 years | NA | NA | 57 | 19.4 (8.7) | NA | NA |

| p value (test) | 0.879 (MWc) | |||||

Radiation-Induced CD8 T-Lymphocyte Apoptosis.

Standard Deviation.

Mann Whitney.

Radiation Therapy.

Radio-Induced Sarcoma.

There was no significant association between hormone therapy for the initial cancer and RILA, either in the whole population or in the subpopulation of RIS patients (p = .159 and p = .905, respectively). Conversely, a significant relationship was observed between RILA and hormone therapy in control patients, whereby patients who received hormone therapy were found to have a lower percentage of RILA (p = .026) (Table 4). Concerning these patients, hormonal treatment delivered for initial cancer, was stopped before blood sampling.

Finally, there was no significant relationship between age at the time of RT, and RILA results (p > .74).

3.6. RILA as predictor of secondary sarcoma risk

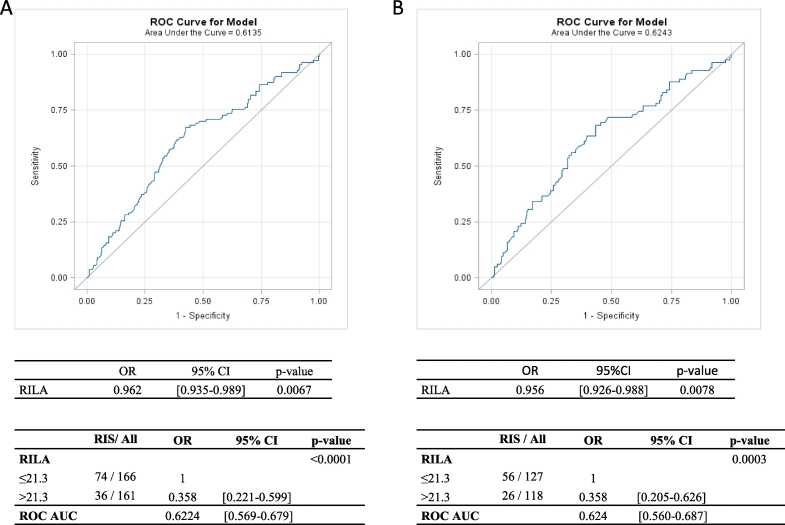

ROC curves analysis of all study patients or patients with primary breast cancer yielded a RILA cut-off of 21.3%. Thus, all patients with RILA ≥21.3% had a comparatively lower risk of developing RIS (p < .0001, OR: 0.358 [0.221–0.599], Fig. 2A), and the results were similar in an analysis limited to patients with primary breast cancer (p = .0003, OR 0.358 [0.205–0.626], Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

ROC curve analysis to determine RILA cutoffs and to calculate sensitivity and specificity (all patients in A, only patients with primary breast cancer in B).

RILA: radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis.

The AUCs were 0.622 [0.569–0.679] for all patients and 0.624 [0.560–0.687] for patients with primary breast cancer (Fig. 2 A and B, respectively).

4. Discussion

The aim of this translational multicenter study was to investigate the ability of RILA to predict the development of RIS. SARI is the first large-size prospective study exploring the biological characteristics of patients who developed RIS after a primary cancer, in contrast with previous publications, which focused mainly on radio-induced breast angiosarcoma [[35], [36], [37]]. Our results found a median latency from RT to the diagnosis of RIS of 10.1 years, consistent with other studies indicating a period between 6 and 20 years [[16], [17], [18],[38], [39], [40]].

We initially selected adult patients with sarcoma within a group of RIS patients to avoid potential confounding factors for sarcoma development. None of our patients had identified risk factors for developing RIS such as unspecific genetics factors (Li-Fraumeni-Syndrome [41]), young age at radiotherapy or concomitant chemotherapy associated with secondary carcinoma [39,40]. To minimize the role of potential prior risk factors, RIS patients were matched with control patients exhibiting similar characteristics (age at RT, sex and breast cancer localization to reduce RT dose and variability of fractionation). The proportion of patients receiving chemotherapy was similar between these two cohorts. This result allowed to reduce the impact of this type of treatment on RIS development, as previously described for anthracycline molecules, as well as other cytotoxic agents, a known risk factor associated with secondary sarcomas in childhood cancer survivors [42]. However, in our study we didn't collect chemotherapy details for all patients. Therefore, the relationship between anthracycline treatment and RIS development was not specifically evaluated in our cohort.

In order to develop personalized medicine in RT, clinicians need to be able to predict potential radio-induced adverse events such as secondary sarcomas, which are rare but deleterious. In the literature, the five-year survival rate for RIS patients is estimated to be between 10 and 36% [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]], lower than the survival rate for patients with sporadic sarcomas (from 54% to 76%) [11,15,36,43]. Previous studies have also revealed that variations in prognostic criteria yield a significant difference in overall survival of RIS patients. For example, sarcoma-related survival was significantly better for patients with a RIS tumor of <5 cm (p = .008) [35]. Firstly, patients at risk should be offered alternative therapeutic options to minimize the risk of severe late events. Secondly, patients at risk of developing RIS should have a personalized follow-up, which could enable screening and earlier diagnosis of tumors, thus offering a better chance of cure. A personalized follow up of patients undergoing RT would require a robust biological marker able predict the development of RIS. Ideally, this marker should be inexpensive, have a simple quantification method and allow a large scale use. The RILA biomarker has already been described as a predictor of late RT-related adverse event, such as the risk of grade ≥ 2 radio-induced breast fibrosis using the CTCAE validated scale [33]. Currently, the pioneer team that developed the RILA parameter, didn't completely elucidate the mechanism linking RILA and radio-induced toxicity. It has been suggested that this relationship could be due to a slow apoptotic response and enhancement of cytokine production, leading to tissue inflammatory cell infiltration [29]. A specific study, using a proteomic approach, is presently ongoing to evaluate the underlying mechanism [33].

Although a large majority of our patients had a primary breast cancer, our analysis was performed in the whole population, as established by the protocol. Identical results were observed when the analysis was restricted to the breast cancer sub-population. Concerning other initial cancer localizations, as head and neck and pelvis, results could not be rigorously validated due to lack of statistical power. Another subgroup analysis concerning only patients with non-breast cancer as primary disease didn't highlight significant relationship between RIS and RILA (Supplementary Table 1). These results were be able to be explain by a specific relationship between RIS and RILA only for breast cancer as primary disease or by a lack of statistical power due to a low numbers of analyzed patients for this analysis (28 RIS patients and 54 control patients).

Given that for RIS patients, blood was collected after RIS diagnosis and that for control patients, blood was collected during follow-up and the majority of these patients had a relapse free status, we cannot totally exclude that RILA fraction might be a marker of tumor presence in general, rather than a predictor of RIS. To decrease this risk, we compared our cohort results with other trials evaluating RILA for patients with or without cancer at sample time. In our RIS cohort, RILA median was 18.5% [5.5–55.7] and in our control patient cohort the RILA median was 22.3% [3.8–52.2], in a large breast cancer cohort (n = 456; [33]) the RILA median was 15.2% [0.7–52.8], and finally in the EPOPA cohort [44] which analyzed 224 patients treated by radiotherapy for a prostate cancer since several years, the majority of these patients presented a relapse free status, the RILA median was 15.3% [4.4–37.7]. These data didn't highlight an increase in RILA in patients without cancer, suggesting that the difference of RILA between our two cohorts were independent of cancer presence at the moment of RILA analysis.

In our present study, with an AUC of 0.62, the 21.3% RILA cut off was low in sensitivity and specificity and, consequently, we cannot promote the use of this biomarker alone. It will be of key importance to build a specific nomogram model combining relevant data such as genetic markers, to improve sensitivity and specificity for event prediction on a population basis. A final validation process in a prospective randomized phase III trial would be necessary before introducing RILA testing in routine practice for patients with significant long time overall survival probability after radiotherapy. For patients identified with a high risk of developing RIS, radiation oncologists should be in a position to inform the patient, to discuss alternative therapeutic options and to suggest early personalized follow-up with non-invasive methods such as relevant imaging.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article

RILA percent distribution for RIS (red) and Control patients (blue)

RILA analysis for RIS and Control patients with non-breast cancer as primary disease

Data Sharing

No data sharing plan has been notified in informed consent form. Consequently, individual data could not be share. However, anonymized and statistical data are available and might be verified.

Declaration

CGFL (Centre Georges François Leclerc, Dijon, FRANCE) received an unrestricted educational grant (PHRC 2011) to cover the expenses of the investigators for undertaking this trial. All authors declared no conflict of interests related to this article.

Author contributions

P.M, F·B, F.C., and C.M. were involved in the conception and design of the study. G.T, G.N., J.T., J.D., P.S., S.RO., I.RC., X.L., JL.L., MA.M., P.M., JL.M. were involved in the provision of patients, data acquisition and helped to draft the report.

P.M. and C.M. supervised the study. A.B. was in charge of the statistical analysis of the study. C.M., P.M. and A.B. had access to the raw data and analyzed and interpreted the data. C.M., P.M., A.B. were involved in report writing, which was corrected and approved by all authors.

Roles of the funding sources

Funding sources didn't participate in the study's design and didn't access the data generated by this trial.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the French INCa “Program Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRC)”. The authors would like to thank JM Coindre for his sarcoma expertise, C Grisi, E Rederstorff, and J Skrzypski for their help organizing this multicenter study, all clinical research technicians for collecting clinical data and J Blanc for her significant help with statistical analysis. The authors also thank M Husson for performing RILA testing. They also thank F Ecarnot (EA3920, University Hospital Besançon, France) and I Gregoire (medical writer, CGFL, Dijon, France) for critical review and editorial assistance.

Footnotes

These results have been presented by a selected oral presentation during Amsterdam ECCO meeting in January 2017 (Sarcoma in irradiated area (SARI): radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocytes apoptosis as a potential predisposition factor: Results of the SARI trial").

References

- 1.Lindholm C., Cavallin-Stahl E., Ceberg J., Frodin J.E., Littbrand B., Moller T.R. Radiotherapy practices in Sweden compared to the scientific evidence. Acta Oncol. 2003;42(5–6):416–429. doi: 10.1080/02841860310012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady M.S., Garfein C.F., Petrek J.A., Brennan M.F. Post-treatment sarcoma in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1(1):66–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02303543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraga-Guedes C., Gobbi H., Mastropasqua M.G., Botteri E., Luini A., Viale G. Primary and secondary angiosarcomas of the breast: a single institution experience. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(3):1081–1088. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jallali N., James S., Searle A., Ghattaura A., Hayes A., Harris P. Surgical management of radiation-induced angiosarcoma after breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg. 2012;203(2):156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirova Y.M., Vilcoq J.R., Asselain B., Sastre-Garau X., Fourquet A. Radiation-induced sarcomas after radiotherapy for breast carcinoma: a large-scale single-institution review. Cancer. 2005;104(4):856–863. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West J.G., Qureshi A., West J.E., Chacon M., Sutherland M.L., Haghighi B. Risk of angiosarcoma following breast conservation: a clinical alert. Breast J. 2005;11(2):115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yap J., Chuba P.J., Thomas R., Aref A., Lucas D., Severson R.K. Sarcoma as a second malignancy after treatment for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(5):1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arlen M., Higinbotham N.L., Huvos A.G., Marcove R.C., Miller T., Shah I.C. Radiation-induced sarcoma of bone. Cancer. 1971;28(5):1087–1099. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:5<1087::aid-cncr2820280502>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cahan W.G., Woodard H.Q., Higinbotham N.L., Stewart F.W., Coley B.L. Sarcoma arising in irradiated bone: report of eleven cases. 1948 Cancer. 1998;82(1):8–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980101)82:1<8::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladdy R.A., Qin L.X., Moraco N., Edgar M.A., Antonescu C.R., Alektiar K.M. Do radiation-associated soft tissue sarcomas have the same prognosis as sporadic soft tissue sarcomas? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2064–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huvos A.G., Woodard H.Q., Cahan W.G., Higinbotham N.L., Stewart F.W., Butler A. Postradiation osteogenic sarcoma of bone and soft tissues. A clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. Cancer. 1985;55(6):1244–1255. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850315)55:6<1244::aid-cncr2820550617>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J., Mackillop W.J. Increased risk of soft tissue sarcoma after radiotherapy in women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92(1):172–180. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<172::aid-cncr1306>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taghian A., de Vathaire F., Terrier P., Le M., Auquier A., Mouriesse H. Long-term risk of sarcoma following radiation treatment for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(2):361–367. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90783-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark R.J., Poen J., Tran L.M., Fu Y.S., Selch M.T., Parker R.G. Postirradiation sarcomas. A single-institution study and review of the literature. Cancer. 1994;73(10):2653–2662. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940515)73:10<2653::aid-cncr2820731030>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha C., Antonescu C.R., Quan M.L., Maru S., Brennan M.F. Long-term results with resection of radiation-induced soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2004;239(6):903–909. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128686.51815.8b. [discussion 9-10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray E.M., Werner D., Greeff E.A., Taylor D.A. Postradiation sarcomas: 20 cases and a literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45(4):951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagrange J.L., Ramaioli A., Chateau M.C., Marchal C., Resbeut M., Richaud P. Sarcoma after radiation therapy: retrospective multiinstitutional study of 80 histologically confirmed cases. Radiation therapist and pathologist groups of the federation Nationale des centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer. Radiology. 2000;216(1):197–205. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl02197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan J.Y., Wong S.T., Lau G.I., Wei W.I. Postradiation sarcoma after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(12):2695–2699. doi: 10.1002/lary.23282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrido-Colmenero C., Valenzuela-Salas I., Blasco-Morente G., Aneiros-Fernandez J., Tercedor-Sanchez J. Photoletter to the editor: Postradiation sarcoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2016;10(1):17–18. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2016.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt G.E., Thomson A.B., Griffin A.M., Bell R., Wunder J., Rougraff B. Multifocality and multifocal postradiation sarcomas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450:67–75. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229301.75018.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson M.T., Wakely P.E., Jr., Weber K., Siddiqui M.T., Ali S.Z. Postradiation sarcoma: morphological findings on fine-needle aspiration with clinical correlation. Cancer Cytopathol. 2012;120(5):351–357. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sule N., Xu B.O., El Zein D., Szigeti K., George S., Kane J.M. Radiation-induced Chondrosarcoma of the bladder. Case report and review of literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(5):2857–2860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mentzel T., Schildhaus H.U., Palmedo G., Buttner R., Kutzner H. Postradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma after treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 66 cases. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(1):75–85. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentzen S.M., Constine L.S., Deasy J.O., Eisbruch A., Jackson A., Marks L.B. Quantitative analyses of Normal tissue effects in the clinic (QUANTEC): an introduction to the scientific issues. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3 Suppl):S3–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentzen S.M., Overgaard J. Patient-to-patient variability in the expression of radiation-induced Normal tissue injury. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1994;4(2):68–80. doi: 10.1053/SRAO00400068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourgier C., Lacombe J., Solassol J., Mange A., Pelegrin A., Ozsahin M. Late side-effects after curative intent radiotherapy: identification of hypersensitive patients for personalized strategy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;93(3):312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crompton N.E., Ozsahin M. A versatile and rapid assay of radiosensitivity of peripheral blood leukocytes based on DNA and surface-marker assessment of cytotoxicity. Radiat Res. 1997;147(1):55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozsahin M., Ozsahin H., Shi Y., Larsson B., Wurgler F.E., Crompton N.E. Rapid assay of intrinsic radiosensitivity based on apoptosis in human CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocytes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38(2):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozsahin M., Crompton N.E., Gourgou S., Kramar A., Li L., Shi Y. CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis can predict radiation-induced late toxicity: a prospective study in 399 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(20):7426–7433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foro P., Algara M., Lozano J., Rodriguez N., Sanz X., Torres E. Relationship between radiation-induced apoptosis of T lymphocytes and chronic toxicity in patients with prostate cancer treated by radiation therapy: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(5):1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnarr K., Boreham D., Sathya J., Julian J., Dayes I.S. Radiation-induced lymphocyte apoptosis to predict radiation therapy late toxicity in prostate cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(5):1424–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgmann K., Hoeller U., Nowack S., Bernhard M., Roper B., Brackrock S. Individual radiosensitivity measured with lymphocytes may predict the risk of acute reaction after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(1):256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azria D., Riou O., Castan F., Nguyen T.D., Peignaux K., Lemanski C. Radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis as a predictor of breast fibrosis after radiotherapy: results of the prospective Multicenter French trial. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1965–1973. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mirjolet C., Merlin J.L., Dalban C., Maingon P., Azria D. Correlation between radio-induced lymphocyte apoptosis measurements obtained from two French centres. Cancer Radiother. 2016;20(5):391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjerkehagen B., Smastuen M.C., Hall K.S., Skjeldal S., Smeland S., Fossa S.D. Why do patients with radiation-induced sarcomas have a poor sarcoma-related survival? Br J Cancer. 2012;106(2):297–306. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjerkehagen B., Smeland S., Walberg L., Skjeldal S., Hall K.S., Nesland J.M. Radiation-induced sarcoma: 25-year experience from the Norwegian radium hospital. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(8):1475–1482. doi: 10.1080/02841860802047387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berrington de Gonzalez A., Kutsenko A., Rajaraman P. Sarcoma risk after radiation exposure. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2(1):18. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Depla A.L., Scharloo-Karels C.H., de Jong M.A., Oldenborg S., Kolff M.W., Oei S.B. Treatment and prognostic factors of radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS) after primary breast cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(10):1779–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawkins M.M., Wilson L.M., Burton H.S., Potok M.H., Winter D.L., Marsden H.B. Radiotherapy, alkylating agents, and risk of bone cancer after childhood cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(5):270–278. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.5.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menu-Branthomme A., Rubino C., Shamsaldin A., Hawkins M.M., Grimaud E., Dondon M.G. Radiation dose, chemotherapy and risk of soft tissue sarcoma after solid tumours during childhood. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(1):87–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moppett J., Oakhill A., Duncan A.W. Second malignancies in children: the usual suspects? Eur J Radiol. 2001;38(3):235–248. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(08)00291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henderson TO, Rajaraman P., Stovall M., Constine L.S., Olive A., Smith S.A. Risk factors associated with secondary sarcomas in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(1):224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thijssens K.M., van Ginkel R.J., Suurmeijer A.J., Pras E., van der Graaf W.T., Hollander M. Radiation-induced sarcoma: a challenge for the surgeon. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(3):237–245. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogin G., Merlin J.L., Rousseau A., Peiffert D., Harle A., Husson M. Absence of correlation between radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis and sequelae in patients with prostate cancer accidentally overexposed to radiation. Oncotarget. 2018;9(66):32680–32689. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

RILA percent distribution for RIS (red) and Control patients (blue)

RILA analysis for RIS and Control patients with non-breast cancer as primary disease