Abstract

Enteroviruses comprise a large group of mammalian pathogens that includes poliovirus. Pathology in humans ranges from sub-clinical to acute flaccid paralysis, myocarditis and meningitis. Until now, all the enteroviral proteins were thought to derive from proteolytic processing of a polyprotein encoded in a single open reading frame (ORF). We report that many enterovirus genomes also harbor an upstream ORF (uORF) that is subject to strong purifying selection. Using echovirus 7 and poliovirus 1, we confirmed expression of uORF protein (UP) in infected cells. Using ribosome profiling (a technique for global footprinting of translating ribosomes), we also demonstrated translation of the uORF in representative members of the predominant human enterovirus species, namely Enterovirus A, B, and C. In differentiated human intestinal organoids, UP-knockout echoviruses are attenuated compared to wild-type virus at late stages of infection where membrane-associated UP facilitates virus release. Thus we have identified a previously unknown enterovirus protein that facilitates virus growth in gut epithelial cells – the site of initial viral invasion into susceptible hosts. These findings overturn the 50-year-old dogma that enteroviruses use a single-polyprotein gene expression strategy, and have important implications for understanding enterovirus pathogenesis.

Enteroviruses are ubiquitous worldwide, highly infectious and environmentally stable. While many infections are mild or asymptomatic, some serotypes can cause severe and even fatal disease with symptoms ranging through fever, hand foot and mouth disease, myocarditis, viral meningitis, encephalitis, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, and acute flaccid paralysis. Although the enterovirus that causes poliomyelitis has been eradicated from much of the globe, other emerging enteroviruses can cause severe polio-like symptoms 1. The Enterovirus genus belongs to the Picornaviridae family. Members have monopartite linear positive-sense single-stranded RNA genomes of ~7.4 kb, that are encapsidated into non-enveloped icosahedral virions. Currently, 13 species (Enterovirus A-J and Rhinovirus A-C) and more than 70 serotypes have been defined. The virus genome contains a single long open reading frame (ORF) which is translated as a large polyprotein that is cleaved to produce the viral capsid and nonstructural proteins 2 (Fig. 1a). The 3ʹ end of the genome is polyadenylated and contains signals involved in replication and genome circularization. The 5ʹ end is covalently bound to a viral protein, VPg, and the 5ʹ UTR harbors an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that mediates cap-independent translation.

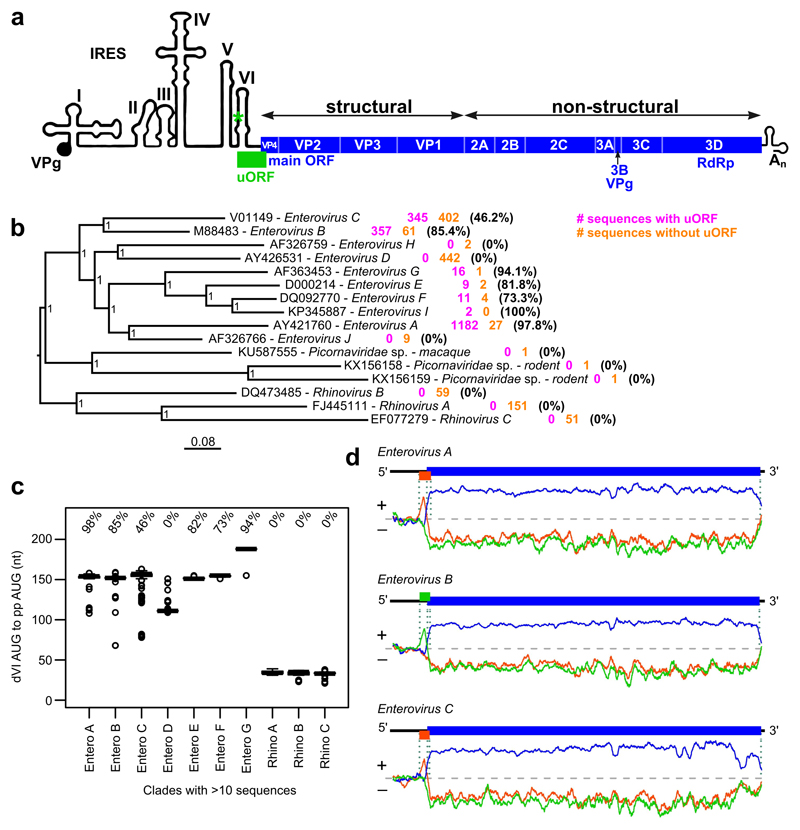

Fig. 1. Comparative genomic analysis of the Enterovirus genus.

a, Schematic representation of the enterovirus genome showing the uORF (green), ppORF (blue), and 5ʹ/3ʹ UTR RNA structures (not to scale). b, Phylogenetic tree for the Enterovirus genus. Within each clade, the number of sequences containing (pink) or not containing (orange) the uORF, and the percentage of sequences containing the uORF are indicated. The tree, calculated with MrBayes, is based on the polyprotein amino acid sequences of the indicated reference sequences, and is midpoint-rooted; nodes are labelled with posterior probability values. c, Box plots of distances between the dVI AUG codon and the polyprotein AUG codon for different enterovirus clades (centre lines = medians; boxes = interquartile ranges; whiskers extend to most extreme data point within 1.5 × interquartile range from the box; circles = outliers; n = sum of sequences with and without the uORF as shown in (a)). In each clade, the percentage of sequences that contain the uORF is indicated. d, Coding potential in the three reading frames (indicated by the three colors) as measured with MLOGD, for sequences that contain the uORF (see Fig. S1b for Enterovirus E, F and G). Positive scores indicate that the sequence is likely to be coding in the given reading frame. Reading frame colors correspond to the genome maps shown above each plot, indicating the ppORF and uORF in the reference sequences EV-A71, EV7 and PV1, respectively.

The enterovirus IRES comprises several structured RNA domains denoted II to VI (Fig. 1a). Ribosome recruitment requires eukaryotic initiation factors eIF2, eIF3, eIF4A, eIF4G, eIF4B and eIF1A but not the cap-binding protein eIF4E 3. Domain VI (dVI) comprises a stem-loop containing a highly conserved AUG codon (586AUG in poliovirus) in a poor initiation context. The dVI AUG plays an important role in stimulating attachment of 43S ribosomal preinitiation complexes to the viral mRNA, which then scan or otherwise migrate to the polyprotein initiation site downstream (743AUG in poliovirus) 4–6. In poliovirus type 1 (PV1), the dVI AUG is followed by a 65-codon upstream ORF (uORF) that overlaps the polyprotein ORF (ppORF) by 38 nt, and some other enteroviruses contain a similarly positioned uORF 3,7. However, multiple previous studies have indicated that the dVI AUG is not itself utilized for initiation 6–8, and the 6.5–9.0 kDa protein that might result from uORF translation has never been detected in enterovirus-infected cells. The “spacer” sequence between dVI and the polyprotein AUG contains little obvious RNA structure and indeed is not particularly well-conserved at the nucleotide level. Despite three decades of research, its function remains unknown.

Here we performed a comparative analysis of >3000 enterovirus sequences, from which we show that the uORF is largely conserved in major enterovirus groups and the encoded amino acids are subject to strong purifying selection indicating that it encodes a functional protein. We used ribosome profiling to demonstrate translation of the uORF in three enterovirus species. Moreover, we show that knocking out expression of the uORF protein (termed UP) significantly attenuates virus growth in differentiated mucosa-derived human intestinal organoids but not in standard cell culture systems, suggesting a specific role for UP during establishment of productive virus infection in gut epithelia in the initial stages of virus invasion of susceptible hosts.

We obtained all full-length enterovirus sequences from GenBank, clustered these into species, and identified the dVI AUG in each. Sequences were defined as having the uORF if the ORF beginning with this AUG codon overlaps the 5ʹ end of the ppORF and contains at least 150 nt upstream of the polyprotein AUG codon. The majority of Enterovirus A, B, E, F and G sequences and around half of Enterovirus C sequences contain an intact uORF (Fig. 1b). In contrast, the uORF is absent from Rhinovirus A, B and C, and Enterovirus D sequences. Clades without the uORF, particularly the rhinoviruses, tend to have a much shorter spacer between the dVI AUG and the polyprotein AUG (Fig. 1c). Although Enterovirus D sequences have a mid-sized spacer (Fig. 1c), the dVI AUG-initiated ORF has just 5 codons in 437 of 442 sequences, and there is no alternative uORF beginning at a different site. Translation of the uORF, where present, in Enterovirus A, B, C, E, F and G would produce a peptide of 56–76 amino acids, 6.5–9.0 kDa, and pI 8.5–11.2 (median values by group; Table S1; Fig. S1a). The 3ʹ quarter of the uORF overlaps the ppORF in either the +1 or +2 frame (Table S1) leading to differing C-terminal tails in UP.

Although the uORF is not present in all sequences, we wished to ascertain whether, where present, it is subject to purifying selection at the amino acid level. To test this we used MLOGD 9 and codeml 10. Codeml measures the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) across a phylogenetic tree; dN/dS < 1 indicates selection against non-synonymous substitutions, which is a strong indicator that a sequence encodes a functional protein. Application of codeml to within-species uORF alignments (excluding the overlap region) resulted in dN/dS estimates in the range 0.04 to 0.22 for Enterovirus A, B, C, E, F and G (Table S1). MLOGD uses a principle similar to dN/dS but also accounts for conservative amino acid substitutions (i.e. similar physico-chemical properties) being more probable than non-conservative substitutions in biologically functional polypeptides. MLOGD 3-frame “sliding window” analysis of full-genome alignments revealed a strong coding signature in the ppORF (as expected) and also in the uORF, with this result being replicated independently for each of the six enterovirus species (Fig. 1d and Fig. S1b).

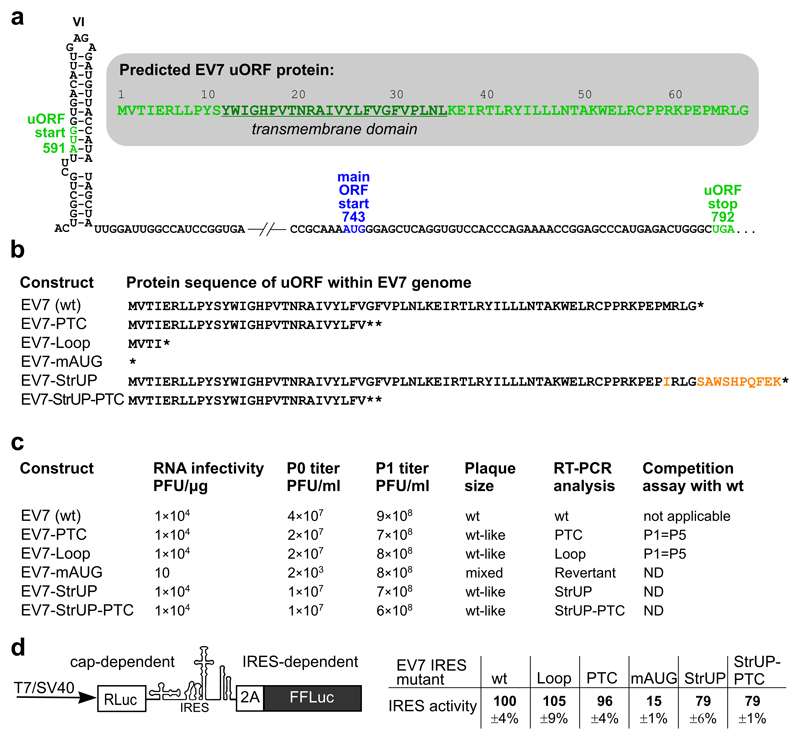

To evaluate the significance of UP in virus infection, we first utilized an infectious clone of echovirus 7 (EV7), a member of the species Enterovirus B. In EV7, the predicted UP protein is 8.0 kDa, has a pI of 10.5, and a predicted transmembrane (TM) domain (Fig. 2a). A set of mutant virus genomes was created and tested for RNA infectivity, virus titer, plaque size, stability of the introduced mutations, competitive growth with wild-type (wt) virus, and relative IRES activity in a dual luciferase reporter system. Mutants with premature termination codons (PTC) introduced at uORF codons 5 or 29 (EV7-Loop and EV7-PTC, respectively; Fig. 2b and Fig. S2a) behaved similarly to wt EV7 in all tested assays (Fig. 2c-d and Fig. S3a), indicating that UP is not required in the context of the susceptible RD cell line.

Fig 2. Analysis of wt and mutant EV7 viruses.

a, Schematic representation of the EV7 IRES dVI and uORF region with the uORF start and stop (green) and main ORF start (blue) annotated. The UP amino acid sequence is shown in the shadowed inset with the predicted TM domain underlined. b, Predicted UP amino acid sequences for the wt and mutant EV7 viruses. c, The infectivity of in vitro-synthesized viral RNAs (in PFUs per 1 µg T7 RNA), the titers of the viruses after transfection (P0) and one passage in RD cells (P1), the comparative plaque sizes (see also Fig. S3a), RT-PCR analysis of viral RNA isolated after three passages in RD cells, and the results of the competition assay (see also Fig. S3b). d, Analysis of relative IRES activities by dual-luciferase reporter assay in HEK293T cells. Schematic representation of the modified pSGDluc expression vector to measure initiation at the polyprotein AUG (left). Relative IRES activities normalized to cap-dependent signal and wt EV7 IRES activity (means ± s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent experiments) (right).

Consistent with previously published poliovirus data 4,7, mutating the EV7 dVI AUG (591AUG) to AAG with a compensatory 615A-to-U mutation to maintain the stem-loop base-pairing (EV7-mAUG; Fig. 2b and Fig. S2a) resulted in a substantial drop in IRES activity to 15% of wt (Fig. 2d). This drop in IRES activity likely explains the attenuated virus growth followed by 100% reversion occurring after the second passage in RD cells (Fig. 2c). Consequently the EV7-mAUG mutant was not used for further uORF studies.

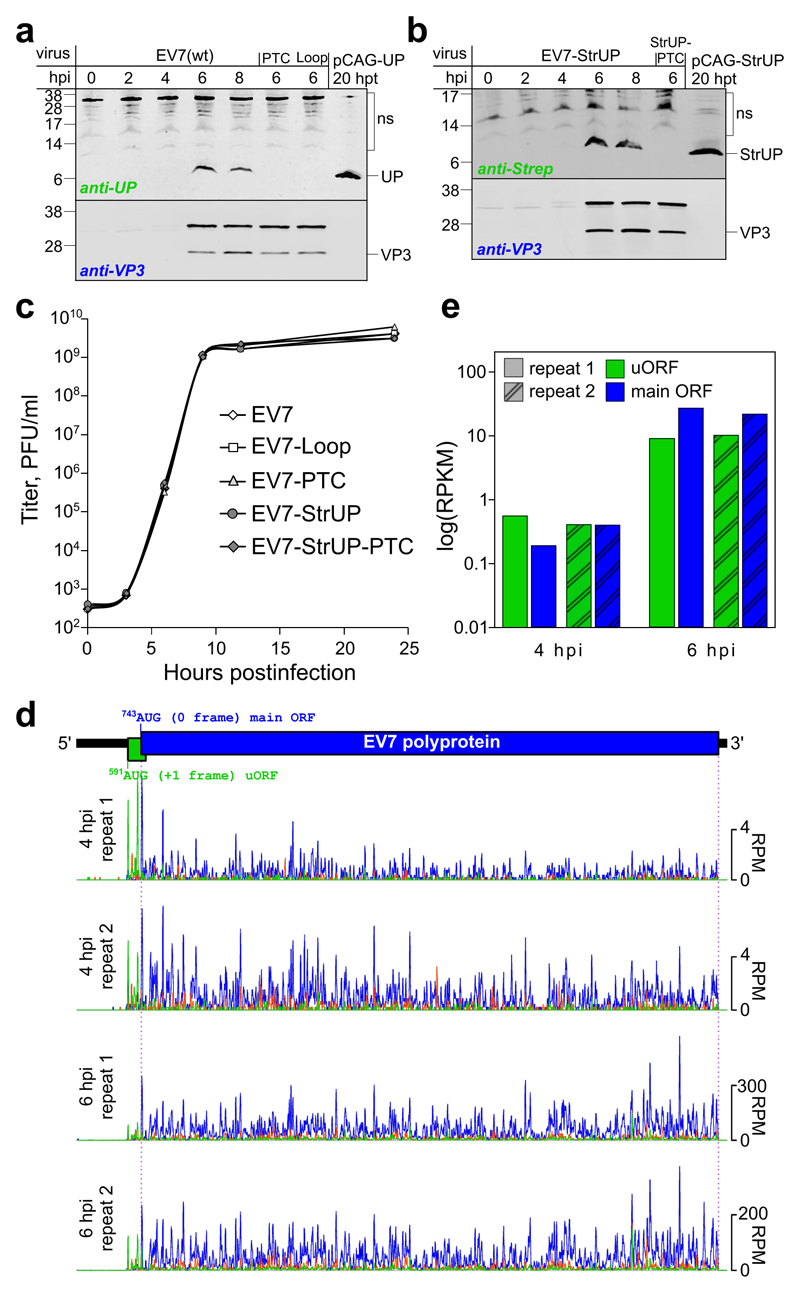

We next sought to determine whether UP is expressed during virus infection. To facilitate this, a version of EV7 designed to produce C-terminally Strep-tagged UP and a corresponding PTC control (EV7-StrUP and EV7-StrUP-PTC; Fig. 2b and Fig. S2b) were created. IRES activity dropped to 80% wt for both EV7-StrUP and EV7-StrUP-PTC (Fig. 2d); nevertheless, this did not noticeably affect the RNA infectivities, virus titers, plaque size, or stability of the introduced mutations (Fig. 2c). We then infected RD cells at high multiplicity of infection (MOI) with wt or mutant viruses and analyzed cell lysates by immunoblotting. A protein migrating at the expected size was detected in 6 and 8 h post infection (hpi) lysates from cells infected with EV7 or EV7-StrUP viruses (with anti-UP and anti-Strep antibodies, respectively), but not for cells infected with the PTC mutants, thus confirming expression of UP (Fig. 3a-b, upper panels). Further analyses confirmed that the introduced mutations did not affect virus structural protein accumulation (Fig. 3a-b, lower panels; Fig. S11a), or virus growth kinetics in one-step growth curves in RD cells (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Timecourse of UP expression in EV7-infected cells.

a, Analysis of viral protein expression in RD cells infected with wt or mutant EV7 viruses. Cells were infected at an MOI of 50, harvested at 0–8 hpi as indicated, and accumulation of UP and virus structural protein VP3 was analyzed by western blotting with anti-UP and anti-VP3 antibodies. UP transiently expressed from a pCAG promoter in HeLa cells taken at 20 h post-transfection was used as a UP size control. b, Analysis of viral protein expression in RD cells infected with wt or mutant Strep-tagged EV7 viruses. Cells were infected at an MOI of 50, harvested at 0–8 hpi as indicated, and accumulation of Strep-tagged UP (StrUP) and VP3 was analyzed by western blotting with anti-Strep and anti-VP3 antibodies. StrUP transiently expressed from a pCAG promoter in HeLa cells taken at 20 h post-transfection was used as a StrUP size control. The experiments in (a-b) were independently repeated three times with similar results. c, One-step growth curves of rescued viruses. RD cells were infected with P1 stocks of wt or mutant viruses at an MOI of 1. Aliquots of the culture media were collected at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 hpi, and the viral titer in the aliquots was analyzed via plaque assay on RD cells. The results of one out of two replicates are shown (see Fig. S10 for the repeat). d, Ribosome profiling of EV7-infected cells at 4 and 6 hpi. Ribo-Seq RPF densities in reads per million mapped reads (RPM) are shown with colors indicating the three phases relative to the main ORF (blue – phase 0, green – phase +1, orange – phase +2), each smoothed with a 3-codon sliding window. e, Mean ribosome density in the EV7 uORF and main ORF at 4 and 6 hpi, based on the in-phase Ribo-Seq density in each ORF (excluding the overlapping region; RPKM = reads per kilobase per million mapped reads).

To further study virus gene expression, we infected RD cells with wt EV7 and performed ribosome profiling (Ribo-Seq) at 4 and 6 hpi. Ribosome profiling maps the footprints of actively translating 80S ribosomes but not scanning or preinitiation ribosomes. Ribo-Seq quality was assessed as previously described (Fig. S4) 11. For these libraries, ribosome protected fragment (RPF) 5ʹ ends mapped predominantly to the first nucleotide positions of codons (phase 0) (Fig. S4c), thus allowing robust identification of the reading frame in which translation is taking place. Within the ppORF, RPFs mapped predominantly to the first nucleotide positions of polyprotein codons (blue phase). However, within the non-overlapping portion of the uORF, RPFs mapped predominantly to the first nucleotide positions of uORF codons (green phase) (Fig. 3d and Fig. S4d) confirming uORF translation. Ribosome density in the uORF was comparable to ribosome density in the ppORF (Fig. 3d-e). With our Ribo-Seq protocol, a peak in RPF density is frequently observed on initiation sites (Fig. S4a). Consistently, the first peak in the green phase mapped precisely to the dVI AUG codon (Fig. 3d and Fig. S4d).

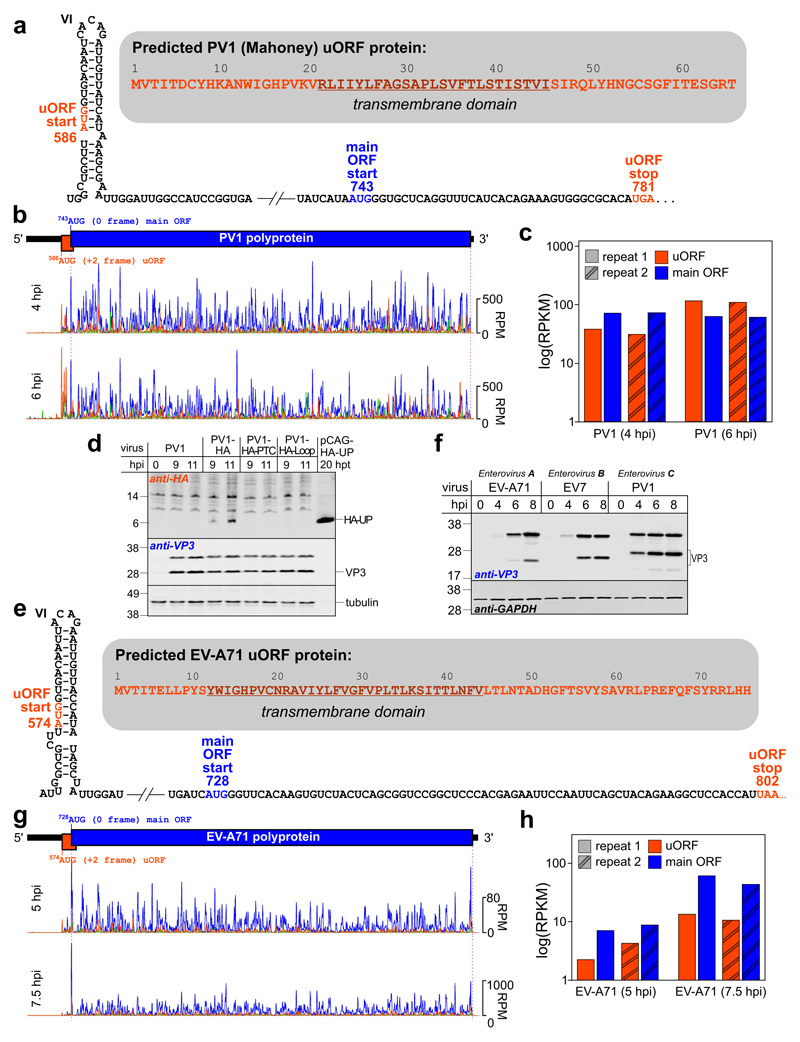

To confirm translation of UP in other enteroviruses we performed ribosome profiling with PV1 and EV-A71, members of the species Enterovirus C and A, respectively. PV1 is a causative agent of poliomyelitis whereas EV-A71 is one of the major causative agents of hand, foot and mouth disease. Both viruses have the potential to cause severe neurological disease. For both PV1 and EV-A71, the uORF initiation site within the 5ʹ RNA structure and the UP protein properties are similar to those of EV7 (Fig. 4a and 4e). The predicted UP is 7.2 kDa with a pI of 9.2 in PV1 and 8.8 kDa with a pI of 9.5 in EV-A71, and both UPs have a predicted TM domain.

Fig. 4. Translation of the uORF in poliovirus PV1 and enterovirus EV-A71.

a, Schematic representation of the PV1 IRES dVI and uORF region with the uORF start and stop (orange) and main ORF start (blue) annotated. The UP amino acid sequence is shown in the shadowed inset with the predicted TM domain underlined. b, Ribosome profiling of PV1-infected cells at 4 and 6 hpi. Ribo-Seq RPF densities in reads per million mapped reads (RPM) are shown with colors indicating the three phases relative to the main ORF (blue – phase 0, green – phase +1, orange – phase +2), each smoothed with a 3-codon sliding window (see Fig. S12a for repeats). c, Mean ribosome density in the PV1 uORF and main ORF at 4 and 6 hpi, based on the in-phase Ribo-Seq density in each ORF (excluding the overlapping region; RPKM = reads per kilobase per million mapped reads). d, Analysis of viral protein expression in RD cells infected with wt or HA-tagged PV1 viruses. Cells were infected at an MOI of 50, harvested at 9 and 11 hpi, and accumulation of HA-tagged UP (HA-UP) and virus structural protein VP3 was analyzed by western blotting with anti-HA, anti-VP3 and anti-tubulin antibodies. HA-UP transiently expressed from a pCAG promoter in HeLa cells taken at 20 h post-transfection was used as a HA-UP size control. e, Schematic representation of the EV-A71 IRES dVI and uORF region with the uORF start and stop (orange) and main ORF start (blue) annotated. The UP amino acid sequence is shown in the shadowed inset with the predicted TM domain underlined. f, Analysis of protein expression in RD cells infected with enteroviruses EV-A71, EV7 or PV1. Cells were infected at an MOI of 20, harvested at 0–8 hpi as indicated, and expression of virus and host proteins was analyzed by western blotting with anti-VP3 and GAPDH antibodies. The experiments in (d,f) were independently repeated three times with similar results. g, Ribosome profiling of EV-A71-infected cells at 5 and 7.5 hpi (see Fig. S12b for repeats). h, Mean ribosome density in the EV-A71 uORF and main ORF at 5 and 7.5 hpi.

The PV1 growth characteristics were found to be similar to those of EV7 – reaching complete cytopathic effect at 7–8 hpi at high MOI. On the other hand, EV-A71 growth was slower with complete cytopathic effect at 10–11 hpi. Consistently, VP3 accumulation in infected cells was fastest in PV1 (4 hpi), followed by EV7 (6 hpi), and slowest in EV-A71 (8 hpi) (Fig. 4f). Hence, for PV1 we used ribosome profiling time points 4 and 6 hpi whereas for EV-A71 we used 5 and 7.5 hpi. Ribo-Seq data quality was assessed as before (Fig. S5 and Fig. S6). In PV1 the uORF is in the +2 frame relative to the ppORF and, once again, within the non-overlapping portion of the uORF RPFs mapped predominantly to the first nucleotide positions of uORF codons (orange phase) (Fig. 4b and Fig. S5d). Similarly to EV7, the PV1 uORF was found to be efficiently translated (Fig. 4b-c) and the first peak in the orange phase mapped precisely to the dVI AUG codon (Fig. 4b and Fig. S5d). For EV-A71, the uORF is also in the +2 frame relative to the ppORF. RPF density in the uORF phase (orange) was substantially lower for EV-A71 than for EV7 and PV1 (Fig. 4g-h and Fig. S6d). Nonetheless, the first peak in the orange phase mapped precisely to the dVI AUG codon (Fig. 4g and Fig. S6d) indicating that the uORF is also translated in EV-A71, but probably at lower efficiency than in EV7 and PV1.

Following the strategy used for EV7, we designed a version of PV1 to produce C-terminally HA-tagged UP, and corresponding PTC and Loop mutant controls (PV1-HA, PV1-HA-PTC and PV1-HA-Loop; Fig. S7a). Tagging resulted in moderate attenuation (Fig. S7b). A protein migrating at the expected size was detected in 11 hpi lysates from RD cells infected with PV1-HA, but not for cells infected with wt PV1 or the PTC or Loop mutants, thus confirming expression of UP during virus infection (Fig. 4d, upper panels). There were no major differences in accumulation of virus structural proteins between the different viruses (Fig. 4d, lower panels; Fig. S11c).

We next investigated possible effects of UP during infection in other cell lines and experimental conditions. Initial tests found no difference between wt and PTC mutants in any permissive cell line tested (MA104, HEK293T, HeLa, CaCo2, Huh7, HGT) at any MOI, even upon induction of an antiviral state by interferon treatment. Working with a mouse-pathogenic poliovirus mutant, Mah(L), an earlier analysis by Slobodskaya and colleagues found that a 103-nt deletion in the 5ʹ UTR (∆S mutant) – that truncates the uORF to 31 codons and fuses it in-frame with the ppORF – resulted in no attenuation; in contrast, mutation of the dVI AUG abrogated neurovirulence, presumably due to its effect on IRES activity 12. Thus we hypothesised that UP might instead play a role at the primary site of infection, namely the gastrointestinal tract, which for many enteroviruses is the critical site of virus amplification before dissemination and further progression of systemic infection 13.

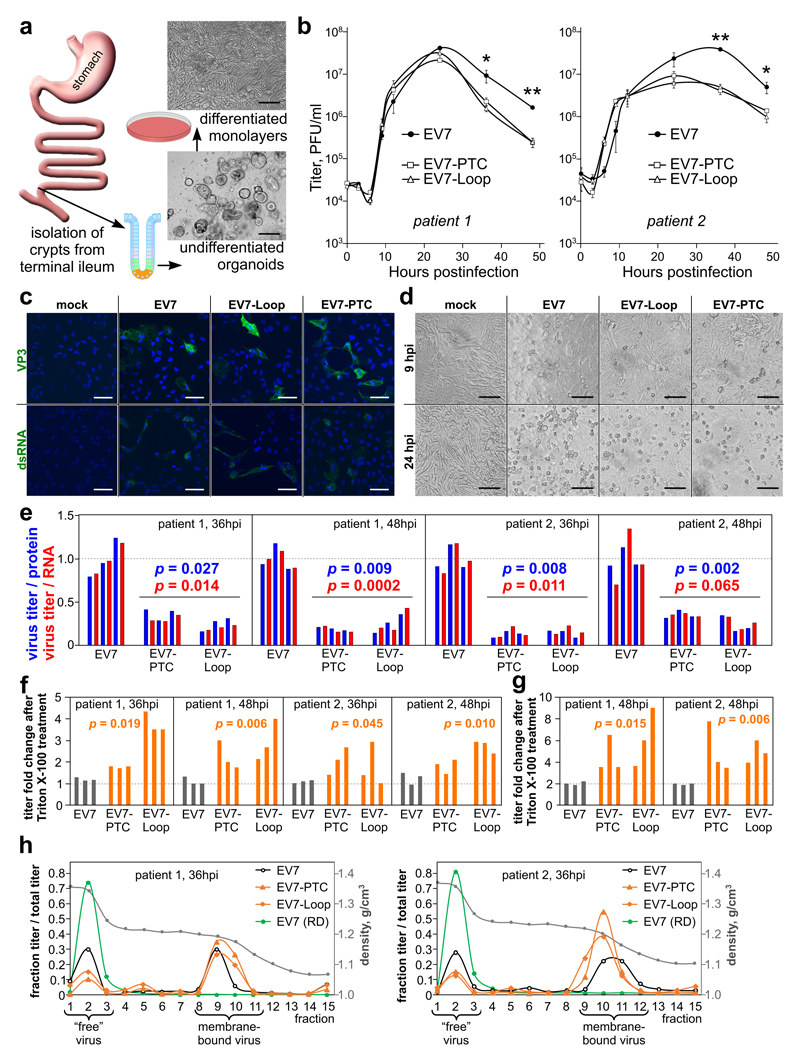

The mouse model for enterovirus infection has several limitations: (i) a requirement for substantial virus adaptation, and immunodeficient or receptor-transgenic mouse strains, (ii) mouse models do not closely mimic human disease, and (iii) although a good model for neurovirulence studies, low sensitivity of the mouse alimentary tract to enterovirus precludes examination of the enteric stage of virus replication. Thus, to address a role for UP in the gastrointestinal tract, we utilized a recently developed human intestinal epithelial organoid platform to examine possible effects of UP in differentiated organoids 14. We generated 3-dimensional organoids derived from distal small bowel (i.e. terminal ileum) mucosal biopsies of patients. Following establishment of cultures, organoids were trypsinized and grown to form differentiated monolayers. Differentiation into epithelial cell subsets, predominantly consisting of absorptive enterocytes, was achieved by withdrawal of wnt agonists as previously described 15,16 (Fig. 5a) and tested by qRT-PCR (Fig. S8). Monolayers were then infected with wt or mutant viruses. At late time points we observed a 75–90% reduction in EV7-Loop or EV7-PTC titers compared to wt EV7 titers (p = 4.6 × 10−5 and 5.5 × 10−5 at 36 and 48 hpi when combined over the two patients; Fig. 5b). For EV7, EV7-Loop and EV7-PTC viruses, the initial infection (6–9 hpi) was restricted to 5–20% of the organoid monolayer (Fig. 5c), which later progressed to complete cytopathic effect by 24–48 hpi (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5. Analysis of EV7 infection in differentiated human intestinal organoids.

a, Schematic representation of production of differentiated intestinal organoids. Crypts are isolated from the terminal ileum intestinal region of patients and grown as undifferentiated organoid cultures (lower image, scale bar 100 µm). After differentiation, the organoids are split into monolayers and grown for 5 days in the presence of growth factors (upper image, scale bar 50 µm). b, Monolayers of differentiated organoid cultures were infected in triplicate with P1 stocks of wt or mutant viruses at MOI 10, washed twice, aliquots of culture media were collected at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 hpi, and viral titer was analyzed via plaque assay on RD cells. The experiment was repeated for organoid cultures originating from two different patients (left and right graphs; means ± s.d.; *, ** p = 0.052, 0.00089 at 36 hpi and 0.0012, 0.046 at 48 hpi for patients 1 and 2 respectively). c, Representative confocal images of mock-infected and infected (EV7, EV7-PTC and EV7-Loop) organoid monolayers at 9 hpi, stained for enterovirus structural protein (VP3, green) or dsRNA (green), and nuclei (Hoechst, blue). Scale bar 50 µm. d, Representative images of mock-infected and infected (EV7, EV7-PTC and EV7-Loop) organoid monolayers at 9 and 24 hpi. Scale bar 50 µm. e, Virus titers normalized by virus protein (blue) or virus RNA (red) for infected differentiated organoid cultures at 36 and 48 hpi. f, Fold differences in virus titers after Triton X-100 treatment of clarified supernatants derived from infected differentiated organoid cultures. g, Fold differences in virus titers after Triton X-100 treatment of lysed cells from infected differentiated organoid cultures at 48 hpi. h, Membrane flotation assay. At 36 hpi, clarified supernatants from infected differentiated organoid cultures were spun in a 60-30-20-10% iodixanol gradient. Fifteen fractions were collected and virus titers determined on RD cells. Virus derived from infected RD cells was used as a control (green line). The density traces are shown in grey. Data represent two (c,d) or three (b,e-g) biologically independent experiments. In (b,e-g), p-values come from comparing the six mutant with three wt values in each group (two-tailed t-tests). See Table S3 for raw data (b,e-h).

To investigate the cause of the growth defect of UP mutants in differentiated human intestinal organoids, we first quantified viral protein and viral RNA in the 36 and 48 hpi samples. However, even after normalizing by protein or RNA, UP mutant titers were still below wt titers [mean fold difference = 0.24; p = 0.00022, 0.000017 (titer/protein) and 0.00016, 0.000016 (titer/RNA) at 36 and 48 hpi when combined over patients; Fig. 5e]. Since UP contains a predicted TM region, we hypothesized that it may play a role in virus release from membranes. Therefore, we subjected the same samples to Triton X-100 detergent treatment (Fig. 5f). This had little effect on wt titers (mean fold increase = 1.2) but increased UP mutant titers (mean fold increase = 2.4) with the change in mutant titers being significantly different from the change in wt titers (p = 0.00087 and 0.000056 at 36 and 48 hpi when combined over patients; Fig. 5f). The lysed cells from 48 hpi were also tested for Triton X-100 mediated virus release. Consistently, the change in mutant titers (mean fold increase = 5.2) was significantly different from the change in wt titers (mean fold increase = 2.0) (p = 0.000086 when combined over patients; Fig. 5g).

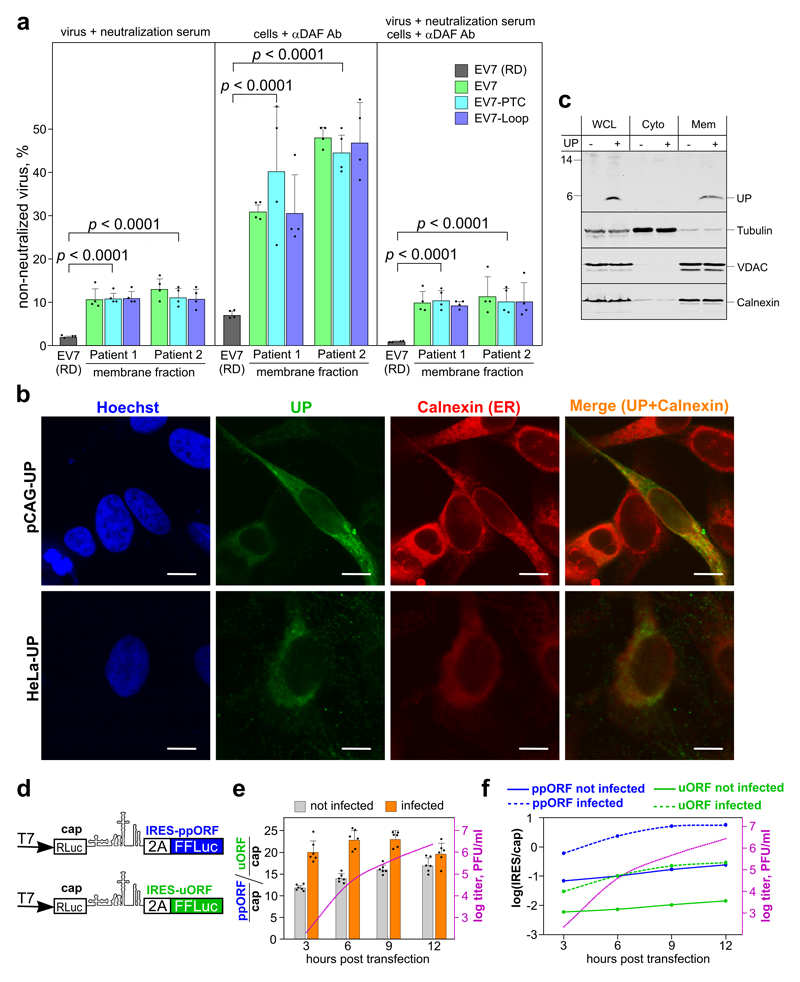

To further test our hypothesis that UP facilitates disruption of organoid-derived membranes, we performed membrane flotation assays for virus-containing media derived from infected differentiated organoid cultures. At 36 hpi, the ratio of membrane-bound to free virus for the EV7-PTC and EV7-Loop mutants exceeded that for wt EV7 by a mean of 3.1 fold (p = 0.026; two-tailed t-test, comparing patient 1 and 2 wt against the four mutant samples; Fig. 5h). In contrast, no membrane-associated virus was detected when the assay was repeated for RD cell-derived EV7 (Fig. 5h, green curve), explaining why no difference between wt and UP-knockout virus titers was observed for these cells. We also compared neutralization of organoid-derived membrane fractions and RD cell-derived virus by treating with EV7 neutralization serum and/or via prevention of receptor-mediated attachment using anti-DAF antibody 17. The flotated membrane fractions were only partially neutralized in all three assays, whereas neutralization of RD cell-derived virus was significantly more efficient (Fig. 6a). Additionally, for RD cell-derived virus the neutralization serum and anti-DAF antibody acted synergistically (p = 0.0004 and 0.0007 for each independent treatment compared to the combined treatment; two-tailed t-tests; Fig. 6a). However, this was not the case for the flotated membrane fractions (Fig. 6a), suggesting that non-neutralized membrane-associated virus enters cells by a route not involving receptor binding – for example via membrane fusion. Taken together, these results suggest that UP plays a role in release of virus particles from membranous components.

Fig. 6. Membrane association of UP and temporal analysis of uORF translation.

a, Fraction of non-neutralized EV7 in RD cell-derived virus and membrane fractions of flotated organoid-derived virus (from Fig. 5h). The membrane fractions for each flotated sample were assayed using (i) virus mixed with EV7 neutralization serum (left panel), (ii) cells pre-incubated with anti-DAF antibody (middle panel), and (iii) both methods simultaneously (right panel) (means ± s.d.; n = 4 biologically independent experiments; p-values come from comparing the 12 organoid-derived samples with the four RD cell-derived samples using two-tailed t-tests). See Table S3 for raw data. b, Representative confocal images of HeLa cells transfected with pCAG-UP, and the HeLa-UP cell line, stained for UP (green), ER (Calnexin, red) and nuclei (Hoechst, blue). The images are averaged single plane scans. Scale bar 10 µm. See Fig. S9 for lower magnification and pCAG control images. c, Fractionation analysis of HeLa cells. Cells were electroporated with pCAG-UP, fractionated, and whole cell lysate (WCL) and cytoplasmic (Cyto) and membrane (Mem) fractions analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to UP, tubulin, VDAC or calnexin as indicated. The experiments in (b-c) were independently repeated three times with similar results. d, Schematic of the modified pSGDluc expression vectors used to measure initiation at the polyprotein (ppORF, in blue) and upstream (uORF, in green) AUG codons. e, Analysis by dual-luciferase reporter assay in HeLa cells of relative IRES activities for ppORF and uORF expression, with and without T7-transcribed infectious EV7 RNA (infected and not infected, respectively). IRES activities were normalized to cap-dependent signal and presented as the ratio ppORF/uORF activity (means ± s.d.). n = 6 biologically independent experiments. Titers from the infected samples measured by plaque assay in RD cells are plotted on a log scale (dotted pink line). f, IRES activities for ppORF and uORF expression relative to cap-dependent expression (i.e. FFLuc/RLuc), with and without co-transfection of T7-transcribed infectious RNA. See Table S4 for raw data (e-f).

Since detectable accumulation of UP in infected cells coincides with strong cytopathic effect that leads to autofluorescence, we studied the subcellular localization of UP in transfected HeLa cells as well as in a stably expressing HeLa cell line. This revealed an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated pattern confirmed by co-staining with calnexin, an ER marker (Fig. 6b and Fig. S9). We also confirmed membrane association of UP by subcellular fractionation of UP-expressing HeLa cells and subsequent analysis of the fractions (Fig. 6c).

As a result of variations in translational speed (including pausing, and potential stacking behind ribosomes initiating at the polyprotein AUG), besides nuclease, ligation and PCR biases introduced during library preparation, ribosome profiling may not provide an accurate estimation of protein expression levels, particularly for short ORFs 11. Therefore, to investigate the relative level of uORF expression, we used dual-luciferase reporter constructs where the 2A-FFLuc cassette was placed either in the uORF or ppORF reading frame just downstream of the ppORF initiation codon (Fig. 6d). HeLa cells were transfected with the reporter construct with or without co-transfection of T7-transcribed infectious EV7 RNA. The ratio of uORF to ppORF expression did not change greatly over time and, consistent with the poor initiation context of the uORF, ppORF translation was 19–23 times more efficient than uORF translation in the context of virus infection (Fig. 6e). Encoding of UP in a separate ORF may be a strategy to allow expression of UP at a level very different from that of the polyprotein products. As expected, IRES activity (both in the uORF and ppORF reading frames) increased relative to cap-dependent translation as infection progressed (Fig. 6f).

To test whether other members of the family Picornaviridae might also harbor undiscovered proteins encoded by alternative ORFs, we applied our comparative genomic methods to other picornaviruses, revealing putative additional protein-coding ORFs in ten Picornaviridae clades (Fig. S13-S21).

The data presented here demonstrate the existence of an additional protein, UP, encoded by the enterovirus genome. The molecular biology of enteroviruses has been studied for over 50 years, not least because poliovirus is such an important pathogen 18. Even before the poliovirus genome was first sequenced in 1981 19,20, all viral polypeptides were presumed to derive from the single polyprotein 21. The uORF product was likely overlooked due to its small size and low expression level. On the other hand, the function of the apparent “spacer” region between the IRES and the polyprotein initiation site was perplexing, particularly since it is absent in rhinoviruses.

Our analysis now demonstrates that, at least in EV7 (Enterovirus B), this region encodes a small protein, UP, that is not required for basic replication but plays an important role in virus growth in gut epithelial cells, the site of initial viral invasion into a susceptible host. Ribosome profiling revealed uORF translation in three enterovirus species and UP expression in EV7 and PV1 was further confirmed by western blot. Comparative genomic analysis shows that the uORF is predominantly present in Enterovirus A, B, E, F and G and around half of Enterovirus C isolates and, where present, is subject to strong purifying selection. In contrast, the uORF is ubiquitously absent from rhinoviruses which infect the upper respiratory tract instead of the gastrointestinal tract, consistent with UP playing a specific role in gut epithelial cells. At least some enteroviruses that lack UP have in fact been shown to be respiratory viruses 22. It is possible that, in enteric viruses which lack UP, its function may be taken over by another membrane-associated protein such as the viroporin 2B; alternatively it may simply be that their replication or tropism is such that a UP function is not required. Interestingly, the majority of poliovirus type 2 and 3 sequences have only a truncated uORF (mode lengths 38 and 18 codons, respectively), too short to meet our definition of uORF presence. However, most available sequences (203/229) of poliovirus type 1 – the most common serotype – have an intact uORF.

Previous cell-free translation studies had indicated that the dVI AUG was not, or only weakly, utilized as an initiation site in wt PV1, though it can be “activated” if its initiation context is artificially enhanced 7,23. Using an in vitro reconstituted translation system, only trace amounts of 48S complexes were observed to form at the PV1 dVI AUG, and the EV-A71 dVI AUG was not recognized 3. Interestingly, much higher levels of 48S initiation complex formation were observed at the uORF AUG in bovine enterovirus (Enterovirus E) where the dVI stem-loop is less stable. In the context of a cell-free translation system, the same authors found detectable but very inefficient 80S ribosomal complex formation at the PV1 dVI AUG and even lower amounts at the EV-A71 dVI AUG 3,24. Ribo-Seq analysis allowed us to study ribosome occupancy throughout the 5ʹ UTR, in a cellular context, and in the context of virus infection. In contrast to much of the previous in vitro work, this revealed efficient translation of the uORF in EV7 and PV1, and a low level of translation in EV-A71.

While non-enveloped viruses have traditionally been assumed to exit cells via cell lysis, there is increasing recognition of non-lytic release pathways of either free or membrane-bound virus particles 25–27. The late stage of the UP-knockout defect, however, suggests that it is not related to non-lytic release. Enteroviruses also subvert the host autophagy pathway – leading to intracellular double- or single-membraned virus-containing vesicles – and can be released from cells in various membrane-bound forms 26–28. The intriguing drop in UP-knockout virus titers observed at late stages of organoid infections, their rescue upon detergent treatment, and the increased proportion of membrane-associated virus in the absence of UP, suggests the importance of UP as a membrane disruptor to facilitate virus particle release from vesicles peculiar to gut epithelial cell infection.

These data overturn the long-established dogma of a single-polyprotein gene expression strategy in the enteroviruses, and open a new window on our understanding of enterovirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. An increased understanding of the precise role(s) of UP in different enterovirus species, and the differences between Enterovirus C isolates that contain or lack an intact uORF, may lead to new virus control strategies; indeed UP knockout mutants may have applications as attenuated virus vaccines.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses

RD cells (human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line, ATCC, CCL-136), HEK293T cells (human embryonic kidney cell line, ATCC, CRL-3216) and HeLa cells (ATCC, CCL-2) were maintained at 37 °C in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotics. All cells were mycoplasma tested and authenticated by deep sequencing.

The cDNA of Echovirus 7 strain Wallace was sourced from Michael Lindberg (GenBank accession number AF465516, with silent substitution 1687G-to-A), and was cloned downstream of a T7 RNA promoter. The cDNA of wt PV1 (strain Mahoney, GenBank accession number V01149.1, with substitutions 2133C-to-T and 2983A-to-G) was sourced from Bert Semler, University of California, and was cloned downstream of a T7 RNA promoter with a hammerhead ribozyme at the 5′ end as previously described 29. Enterovirus EV-A71 strain B2 MS/7423/87 (GenBank accession number MG432108) was plaque-purified using RD cells, sequenced, titrated on RD cells and used for ribosome profiling infections. EV7, PV1 and mutant viruses were rescued via transfection of RD cells with T7-transcribed RNAs using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen). RNA infectivity was assessed by infectious center assay where RD monolayers were overlaid with dilutions of a suspension of RNA-transfected RD cells, incubated for 3 h, overlaid with 1.5% low melting point agarose (catalog number 16520-100; Invitrogen) in DMEM containing 1% FBS, and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C until the formation of plaques. Alternatively, to collect recovered viruses, the transfection medium was replaced with DMEM containing 1% FBS and incubation was continued for 20 h until the appearance of 100% cytopathic effect. Virus stocks were amplified on RD cells, cleared by centrifugation, purified through a 0.22 µm filter, titrated on RD cells and used for subsequent infections. All mutant viruses were also passaged at least 3 times at low MOI (0.01–0.1). The final virus stocks were used for RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis to confirm the presence or reversion of the introduced mutations.

Plasmids

For mammalian expression of UP, the coding sequence of EV7 UP, EV7 UP with C-terminal Strep-tag, or PV1 UP with C-terminal HA-tag was inserted in vector pCAG-PM 30 using AflII and PacI restriction sites. The resulting constructs designated pCAG-UP, pCAG-StrUP, and pCAG-HA-UP, respectively, were confirmed by sequencing.

All EV7 (Fig. S2) and PV1 (Fig. S7) mutations were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis of the pT7-EV7 or pT7-PV1 infectious clone, respectively, and confirmed by sequencing. For Strep-tagged EV7 and HA-tagged PV1, the uORF/ppORF overlap was duplicated and synonymously mutated to avoid recombination (see Fig. S2b and Fig. S7a, respectively, for details). The resulting plasmids were linearized with XhoI (EV7) or EcoRI (PV1) prior to T7 RNA transcription.

For assessing relative IRES activity in a reporter system, the pSGDLuc vector was used to design a cassette having a cap-dependent Renilla luciferase gene followed by 748 nucleotides of 5ʹ-terminal EV7 sequence (entire 5ʹ UTR and first 2 ppORF codons) fused in frame with the 2A firefly luciferase gene 31. To assess IRES activity in the uORF reading frame, the 2A firefly luciferase gene was fused after the 7th nucleotide of the ppORF. The resulting plasmids were linearized with BamHI prior to T7 RNA transcription.

RNA transcript preparation

Transcription reactions were performed with T7 RNA polymerase MEGAscript T7 transcription kit (Ambion). Ten microliter transcription reactions were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and terminated by treatment with DNase I for 15 min at 37 °C.

Reporter assay for relative IRES activity

HEK293T cells were transfected in triplicate with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), using the protocol in which suspended cells are added directly to the RNA complexes in 96-well plates. For each transfection, 100 ng of purified T7 RNA (RNA Clean and Concentrator, Zymo research) plus 0.3 µL Lipofectamine 2000 in 20 µL Opti-Mem (Gibco) supplemented with RNaseOUT™ (Invitrogen; 1:1,000 diluted in Opti-Mem) were added to each well containing 105 cells. Transfected cells in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined using the Dual Luciferase Stop & Glo Reporter Assay System (Promega). IRES activity was calculated as the ratio of Firefly (IRES-dependent translation) to Renilla (cap-dependent translation), normalized by the same ratio for wt EV7 sequence. Three independent experiments were performed to confirm the reproducibility of the results. For temporal analysis of the ppORF:uORF expression ratio, a similar protocol was used but with HeLa cells to support EV7 replication. EV7 infection was achieved by co-transfection of capped T7 EV7 RNA (150 ng per transfection), and the released virus was titrated by plaque assay on RD cells.

Virus competition assay

Dual infection/competition assays were performed in duplicate on RD cells using mutant and wt EV7 at either equal or 9:1 proportions at total MOI 0.1. Mono-infections by wt or mutant viruses were used as controls. Media collected from infected plates was used for 5 blind passages using 1:10,000 volume of obtained virus stock (corresponds to MOI 0.05–0.2). RNA was isolated from passages 1 and 5 using Direct-zol™ RNA MicroPrep (Zymo research) and used for RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing of the fragment containing the mutated region of the virus genome. The final chromatograms were compared and evaluated based on three RT-PCR products from each analyzed sample (Fig. S3b).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Lysates from virus-infected or pCAG-transfected cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, using standard 12% SDS-PAGE to resolve virus structural proteins and precast Novex™ 10–20% tricine protein gels (Thermo fisher) to resolve UP. Proteins were then transferred to 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 4% Marvel milk powder in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Immunoblotting of the enterovirus VP3 structural protein was performed using Enterovirus pan monoclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher, MA5-18206) at 1:1,000 dilution. A custom rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against C-terminal UP peptide CPPRKPEPMRLG (GenScript), an anti-Strep mouse antibody (Abcam, ab184224), and an anti-HA mouse antibody (Abcam, ab130275) were used for detection of EV7 UP, EV7 Strep-tagged UP, and PV1 HA-tagged UP, respectively. The following antibodies were used for cellular targets: anti-tubulin (Abcam, ab15568), anti-VDAC1 (Abcam, ab14734), anti-GAPDH (Ambio, AM4300) and anti-calnexin (Merck, MAB3126). To ensure synchronicity of infection, a high MOI was used for virus infections. Immunoblots were imaged and analyzed on a LI-COR imager. The original LICOR scans and quantifications are shown in Fig. S11.

Sampling, preparation and infection of human intestinal organoid monolayers

Following ethical approval (REC-12/EE/0482) and informed consent, intestinal biopsies were collected from the terminal ileum of patients undergoing routine endoscopy. All patients included had macroscopically and histologically normal mucosa. Biopsy samples were processed immediately and intestinal epithelial organoids generated from isolated crypts following an established previously described protocol 15,16.

To form differentiated monolayers for infection, 48-well plates or IBIDI 8-well chamber slides were collagen-coated 2 h prior to cell seeding. Mature intestinal organoids were washed with PBS with 0.5 mM EDTA and dissociated in 0.5% Trypsin-EDTA. Trypsinization was inactivated by FBS and clumps of cells removed using a 40 µm cell strainer. Cells were seeded at 1.4 × 105 per well and grown in proliferation media 16. After 24 h, cells were maintained in differentiation media 14 and differentiation allowed to occur for 5 days prior to infection. Differentiation of monolayers was confirmed by qPCR measurement of stem cell marker leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5), mature enterocyte marker alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and epithelial cell marker villin transcripts at days 0, 3 and 5. Relative fold changes were assessed with the 2−ΔΔCT method using the HPRT1 transcript for normalization.

Monolayers growing in 48-well plates were infected in triplicate at MOI 10 at 37 °C for 1 h, washed twice with serum-free media and overlaid with 250 µL of differentiation media. Aliquots of media corresponding to half the volume were taken at indicated time points and clarified by centrifugation at 6,000 g for 5 min. The lysed cell debris at 48 hpi was collected using 250 µL of differentiation media. All collected samples were titrated on RD cell monolayers using plaque assay as readout. The 48 hpi virus stocks were used for RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis to confirm the presence of the introduced mutations.

Analysis of samples collected from infected human intestinal organoid monolayers

Samples collected at 36 and 48 hpi were used for EV7 RNA and VP3 quantification. The amount of EV7 RNA was determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR). A 20 µl aliquot of each sample was mixed with 4 × 106 plaque forming units (PFUs) of purified Sindbis virus (SINV) stock, which was used for normalization and to control the quality of RNA isolation. RNA was extracted using the Qiagen QIAamp viral RNA mini kit. Reverse transcription was performed using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) using virus-specific reverse primers for SINV (GTTGAAGAATCCGCATTGCATGG) and EV7 (CACCGAATGCGGAGAATTTACC). EV7 and SINV-specific primers were used to quantify corresponding virus RNAs; the primer efficiency was within 95–105%. Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a ViiA 7 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) for 40 cycles with two steps per cycle. Results were normalized to the amount of SINV RNA in the same sample. Fold differences in RNA concentration were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Protein analysis from the same samples was performed by western blot using Enterovirus pan monoclonal antibody at 1:500 dilution. VP3-specific bands were quantified using LI-COR imager software. EV7 titers were normalized by either the RNA or protein quantities and further normalized to the mean value of the wt EV7 samples. The same set of samples was subjected to treatment with Triton X-100 at final concentration 1% or PBS as a control, titrated by plaque assay, and presented as the ratio of Triton X-100 treated to PBS-treated values.

Membrane flotation assay of organoid-derived viruses

Differentiated human intestinal organoid cultures were infected with EV7 and mutants. At 36 hpi, media was collected, clarified by centrifugation at 6,000 g for 5 min, and aliquots were titrated with or without Triton X-100 pre-treatment. EV7 derived from infected RD cells (MOI 1) collected at 20 hpi in serum-free media and clarified by centrifugation at 6,000 g for 5 min was used as a control. Samples were then used for the flotation assay in an iodixanol gradient as described by Vogt et al. 32 with minor modifications. Briefly, each sample was mixed with 1.5 ml 0.25 M sucrose in PBS and 1.5 ml iodixanol (Sigma) resulting in 30% iodixanol concentration. A discontinuous iodixanol gradient consisting of 1 ml 60%, 3 ml 30% (containing the sample), 4 ml 20% and 4 ml 10% iodixanol was layered and spun at 200,000 g for 16 h at 4° C in a SW41Ti rotor. A total of 15 fractions (~800 µl each) were collected using a fractionator. Each fraction was titrated by plaque assay on RD cells. The resulting titers were normalized to the total amount of virus in each sample and plotted.

Neutralization assays

Virus neutralization was performed by mixing virus sample corresponding to 50–500 PFUs (with appropriate dilution for counting input PFUs) with 1:400 dilution of EV7 neutralization serum (Batch nr. 2/69, The Standards Laboratory, Central Public Health Laboratory, London N.W.9., UK), incubating the mixture at room temperature for 30 min, and then plating on monolayers of RD cells for plaque formation. The neutralization assay via prevention of receptor-mediated attachment was performed on monolayers of RD cells pretreated for 1 h with anti-DAF antibody at 1:500 dilution (rabbit, in-house, sourced from David Evans, 33), followed by infection and plaque formation.

Fractionation analysis of UP

For the analysis of overexpressed UP, electroporation of HeLa cells was performed in full media at 240 V and 975 µF using a BioRad Gene Pulser. At 20 h post-electroporation, cells were washed with PBS and fractionated using a subcellular protein fractionation kit for cultured cells (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal aliquots of whole cell lysate, cytoplasmic and membrane fractions were analyzed by western blot using the indicated virus- or cellular target-specific antibodies.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Differentiated human intestinal organoid monolayers were grown on IBIDI 8-well chamber slides and at 5 days post differentiation infected with EV7 or mutants at MOI 10. For the analysis of overexpressed UP, the transfection of HeLa cells was performed using Lipofectamine 2000. For moderately expressed UP, a HeLa cell line stably expressing UP (HeLa-UP) was created using the pCAG-UP construct as previously described 30. At 9 hpi or 20 hpt, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, followed by permeabilization with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (for infected organoids), 0.1% Triton X-100 or 0.2% saponin (for transfected HeLa cells and the HeLa-UP cell line) for 10 min. Cells were blocked in 5% goat serum and incubated sequentially with primary (Enterovirus pan monoclonal antibody, Scions J2 anti-dsRNA IgG2a monoclonal antibody (Scicons, 10010500) or anti-calnexin antibody) and secondary (Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 597-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit, Thermo Fisher, A11001, A21441, A11032) antibodies. Nuclei were counter-stained with Hoechst (Thermo Scientific). The images are a projection of a z-stack (Fig. S9) or single plane image (Fig. 6b) taken with a Leica SP5 Confocal Microscope using a water-immersion 63× objective.

Ribosome profiling

RD cells were grown on 150-mm dishes to reach 90% confluency. Following previous optimization of ribosome profiling during virus infection, we infected cells at a MOI of 20 with EV7, PV1 or EV-A71 virus stocks. At indicated times postinfection, cells were treated with 3 mM cycloheximide for 3 min, flash frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath, and lysed in the presence of 0.36 mM cycloheximide. Cell lysates were subjected to Ribo-Seq based on the previously described protocols 11,34, except Ribo-Zero Gold rRNA removal kit (Illumina), not DSN, was used to deplete ribosomal RNA. Amplicon libraries were deep sequenced using an Illumina NextSeq platform.

Computational analysis of Ribo-Seq data

Ribo-Seq analysis was performed as described previously 11. Adaptor sequences were trimmed using the FASTX-Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit) and trimmed reads shorter than 25 nt were discarded. Reads were mapped to host (Homo sapiens) and virus RNA using bowtie version 1 35, with parameters -v 2 --best (i.e. maximum 2 mismatches, report best match). Mapping was performed in the following order: host rRNA, virus RNA, host RefSeq mRNA, host non-coding RNA, host genome.

To normalize for library size, reads per million mapped reads (RPM) values were calculated using the sum of total virus RNA plus host RefSeq mRNA reads (positive-sense reads only) as the denominator. A +12 nt offset was applied to the RPF 5′ end positions to give the approximate ribosomal P-site positions. To calculate the phasing and length distributions of host and virus RPFs, only RPFs whose 5′ end (+12 nt offset) mapped between the 16th nucleotide 3′ of the initiation codon and the 16th nucleotide 5′ of the termination codon of coding sequences (ppORF for viruses; RefSeq mRNA coding regions for host) were counted, thus avoiding RPFs of initiating or terminating ribosomes. Histograms of host RPF positions (5′ end +12 nt offset) relative to initiation and termination codons were derived from reads mapping to RefSeq mRNAs with annotated coding regions ≥450 nt in length and with annotated 5′ and 3′ UTRs ≥60 nt in length.

Virus uORF and ppORF expression levels (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads; RPKM) were calculated by counting RPFs whose 5′ end (+12 nt offset) mapped within the respective coding region. The region of overlap between the uORF and ppORF was excluded. To mitigate the effect of RPFs potentially deriving from translation of very short overlapping ORFs (Fig. S4d, Fig. S5d and Fig. S6d), and given the high degree of triplet phasing in the data (Fig. S4c, Fig. S5c and Fig. S6c), we only counted RPFs mapping in phase 0 with respect to the uORF or ppORF, as appropriate; these values were then scaled by the ratio of total polyprotein-mapping RPFs to phase-0 polyprotein-mapping RPFs (a value in the range 1.24–1.39, depending on the library). Due to variability in RPF density as a result of variable codon dwell-times besides biases introduced during library preparation, the short length of the uORF, and the possibility of non-specific initiation in other very short ORFs between the uORF AUG and the ppORF AUG, it was not possible to precisely calculate the relative translation efficiencies of uORF and ppORF from the Ribo-Seq data.

Comparative genomic analysis

Genus Enterovirus nucleotide sequences were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) on 2 July 2017. The bona fide polyprotein AUG initiation site was identified in each sequence by alignment to NCBI genus Enterovirus RefSeqs. Sequences that contained the complete ppORF and at least 160 nt upstream were identified and used for further analysis. Patent sequence records, sequences with NCBI keywords “UNVERIFIED”, “STANDARD_DRAFT”, “VIRUS_LOW_COVERAGE” or “VIRUS_AMBIGUITY”, and sequences with >10 ambiguous nucleotide codes (e.g. “N”s) indicative of low quality or incomplete sequencing, were removed, leaving 3136 sequences.

To define enterovirus clades, the following International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) type sequences for 13 genus Enterovirus species were used as reference sequences: Enterovirus A – AY421760, Enterovirus B – M88483, Enterovirus C – V01149, Enterovirus D – AY426531, Enterovirus E – D00214, Enterovirus F – DQ092770, Enterovirus G – AF363453, Enterovirus H – AF326759, Enterovirus I – KP345887, Enterovirus J – AF326766, Rhinovirus A – FJ445111, Rhinovirus B – DQ473485, and Rhinovirus C – EF077279. The 3136 sequences were grouped into clades according to with which reference sequence they shared greatest polyprotein amino acid identity. Only three sequences – namely KU587555, KX156158 and KX156159 – had <65% amino acid identity to any of the 13 reference sequences and these sequences were left unclustered (Fig. 1b). For the sake of simplicity, recombination – a fairly common occurrence within enterovirus species 36 – was ignored. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1b) was constructed using polyprotein amino acid sequences aligned with MUSCLE 37 and processed with Gblocks 38 using default parameters to remove poorly aligned regions (resulting in a reduction from 2461 alignment columns to 1693 alignment columns). A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was estimated using the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo method implemented in MrBayes version 3.2.3 39 sampling across the default set of fixed amino acid rate matrices, with 100,000 generations, discarding the first 25% as burn-in (other parameters were left at defaults). The tree was visualized with FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

In each of the 3136 sequences, the AUG codon in dVI of the IRES was identified based on the conserved sequences surrounding it (typically UU AUG GU[C/G]ACA, or slight variations thereof; dVI AUG in bold). Sequences were defined as having the uORF if the ORF beginning with this AUG codon and including the first in-frame stop codon (a) overlapped the ppORF by at least 1 nt, (b) was not in-frame with the ppORF, and (c) contained at least 150 nt upstream of the polyprotein AUG codon.

The ratios of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS) were estimated using the codeml program in the PAML package 10. To do this in an acceptable computational time, the alignments were reduced to fewer sequences by applying BLASTCLUST (a single-linkage BLAST-based clustering algorithm) 40. First, within each clade, for those sequences containing a uORF according to the above definition, the uORF nucleotide sequences (3′-truncated, after a whole number of codons, to exclude the part overlapping the ppORF) were extracted, clustered with BLASTCLUST (-p F -L 0.95 -b T -S 95, i.e. 95% coverage, >95% nucleotide identity threshold) and, within each BLASTCLUST cluster, a single representative sequence was retained. In order to mitigate the effect of potential sequencing errors, in each cluster the representative sequence was chosen to be the sequence with the most identical copies (with ties broken arbitrarily), or, if there were no duplicated uORF sequences, the sequence closest to the centroid (minimum summed pairwise nucleotide distances from sequence i to all other sequences j within the cluster). This reduced the uORF sequence sets for enterovirus clades A, B, C, E, F and G from 1182, 357, 345, 9, 11 and 16 to 53, 177, 81, 8, 10 and 13 sequences, respectively. In each clade, the remaining nucleotide sequences were translated, aligned as amino acids with MUSCLE, and the amino acid alignment used to guide a codon-based nucleotide alignment (EMBOSS tranalign) 41. Alignment columns with gap characters in any sequence were removed, resulting in a reduction from 53, 52, 54, 51, 51 and 69 to 50, 50, 50, 50, 51 and 44 codon positions in enterovirus clades A, B, C, E, F and G, respectively. PhyML 42 was used to produce a nucleotide phylogenetic tree for each of these sequence alignments. Using these tree topologies, dN/dS was calculated for each alignment with codeml. Standard deviations for the codeml dN/dS values were estimated via a bootstrapping procedure, in which codon columns of the alignment were randomly resampled (with replacement); for each clade, 100 randomized alignments were generated, and their dN/dS values calculated with codeml.

For sequences containing the uORF, coding potential within each reading frame was analyzed using MLOGD 9. First, within each clade, for those sequences containing a uORF according to the above definition, the polyprotein amino acid sequences were determined, clustered with BLASTCLUST (-p T -L 0.95 -b T -S 99, i.e. 95% coverage, >99% amino acid identity threshold) and, within each BLASTCLUST cluster, a single representative sequence was retained using the same procedure as described above for uORF nucleotide sequences but using the polyprotein amino acid sequences. The ICTV reference sequences (as per Fig. 1b) were also retained as reference sequences for the Enterovirus E, F and G clades, whereas EV-A71, EV7 and PV1 were appended and used as the reference sequences for, respectively, the Enterovirus A, B and C clades. This reduced the sequence sets for enterovirus clades A, B, C, E, F and G to 89, 220, 101, 8, 10 and 15 sequences, respectively. For each clade, the remaining polyprotein amino acid sequences were aligned with MUSCLE, processed with Gblocks as described above, and analyzed with PhyML to produce the tree topology for the MLOGD analysis. Then, for each clade, each individual genome sequence was aligned to the reference sequence using code2aln version 1.2 43, and mapped to reference sequence coordinates by removing alignment positions that contained a gap character in the reference sequence. These pairwise alignments were combined to give whole-clade alignments which were analyzed with MLOGD using a 40-codon sliding window and a 1-codon step size. For each of the three reading frames, within each window the null model is that the sequence is non-coding whereas the alternative model is that the sequence is coding in the given reading frame. Positive/negative values indicate that the sequences in the alignment are likely/unlikely to be coding in the given reading frame (Fig. 1d and Fig. S1b).

For the analysis of non-enterovirus taxa within the Picornaviridae family (Fig. S14a–S23a), coding potential within each reading frame was analysed using MLOGD 9 and synonymous site conservation was analysed with SYNPLOT2 44. For these analyses we generated codon-respecting alignments of full-genome sequences using a procedure described previously 44. In brief, each individual genome sequence was aligned to a reference sequence using code2aln version 1.2 43. Genomes were then mapped to reference sequence coordinates by removing alignment positions that contained a gap character in the reference sequence, and these pairwise alignments were combined to give the multiple sequence alignment. These were analysed with MLOGD (see above) using a 40-codon sliding window and a 5-codon step size. To assess conservation at synonymous sites, the polyprotein coding region and any non-overlapping portion of the additional ORF sequence were extracted from the alignment, the polyprotein and additional ORF sequences were concatenated in-frame (where relevant), and the alignment analysed with SYNPLOT2 using a 25-codon sliding window. Amino acid alignments of the complete putative new proteins (Fig. S14b–S23b) were performed with MUSCLE 37.

Transmembrane (TM) domains were predicted with Phobius (EMBL-EBI) 45.

Statistics and Reproducibility

All t-tests are two-tailed and assume separate variances for the two populations being compared. Raw data for the organoid experiments and details of the t-tests performed are reported in Table S3. Raw data for the dual luciferase assays are reported in Table S4.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cambridge NIHR BRC Cell Phenotyping Hub for assistance with confocal microscopy. We thank Trevor Sweeney, Ian Brierley and Eric Jan for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust grant [106207] and European Research Council grant [646891] to A.E.F; and Wellcome Trust grants 097997/Z/11/Z and 207498/Z/17/Z to I.G.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.E.F. and V.L. conceived the project. V.L. performed the experiments. M.Z., K.M.N., M.H., Y.C., and I.G. established the organoid system, prepared and maintained the organoids, and assisted with the organoid experiments. L.S. and N.J.S. established the poliovirus system and helped prepare poliovirus samples. N.I. advised and assisted with the RiboSeq experiments. A.E.F. performed the comparative genomic analyses. A.M.D. analyzed the RiboSeq data. V.L. and A.E.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The sequencing data reported in this paper have been deposited in ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under the accession number E-MTAB-6180.

Ethical statement

All studies were conducted with informed patient and/or carer consent as appropriate, and with full ethical approval; ethical approval was obtained from the NHS Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee East of England, Hertfordshire (REC-12/EE/0482). Informed consent was obtained from all patients/parents prior to participation in accordance with approved study protocols.

References

- 1.Suresh S, Forgie S, Robinson J. Non-polio Enterovirus detection with acute flaccid paralysis: A systematic review. J Med Virol. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jmv.24933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedard KM, Semler BL. Regulation of picornavirus gene expression. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:702–13. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweeney TR, Abaeva IS, Pestova TV, Hellen CUT. The mechanism of translation initiation on Type 1 picornavirus IRESs. EMBO J. 2014;33:76–92. doi: 10.1002/embj.201386124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelletier J, Flynn ME, Kaplan G, Racaniello V, Sonenberg N. Mutational analysis of upstream AUG codons of poliovirus RNA. J Virol. 1988;62:4486–92. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4486-4492.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellen CU, Pestova TV, Wimmer E. Effect of mutations downstream of the internal ribosome entry site on initiation of poliovirus protein synthesis. J Virol. 1994;68:6312–22. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6312-6322.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaminski A, Poyry TAA, Skene PJ, Jackson RJ. Mechanism of Initiation Site Selection Promoted by the Human Rhinovirus 2 Internal Ribosome Entry Site. J Virol. 2010;84:6578–6589. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00123-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pestova TV, Hellen CUT, Wimmer E. A Conserved AUG Triplet in the 5′ Nontranslated Region of Poliovirus Can Function as an Initiation Codon in Vitro and in Vivo. Virology. 1994;204:729–737. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meerovitch K, Nicholson R, Sonenberg N. In vitro mutational analysis of cis-acting RNA translational elements within the poliovirus type 2 5’ untranslated region. J Virol. 1991;65:5895–901. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5895-5901.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firth A, Brown C. Detecting overlapping coding sequences in virus genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irigoyen N, et al. High-Resolution Analysis of Coronavirus Gene Expression by RNA Sequencing and Ribosome Profiling. PLOS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005473. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slobodskaya OR, et al. Poliovirus Neurovirulence Correlates with the Presence of a Cryptic AUG Upstream of the Initiator Codon. Virology. 1996;221:141–150. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond CG, et al. Enteroviruses infect human enteroids and induce antiviral signaling in a cell lineage-specific manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:1672–1677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617363114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ettayebi K, et al. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science. 2016;353:1387–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, et al. Long-term Expansion of Epithelial Organoids From Human Colon, Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s Epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraiczy J, et al. DNA methylation defines regional identity of human intestinal epithelial organoids and undergoes dynamic changes during development. Gut. 2017 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314817. gutjnl-2017-314817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward T, et al. Decay-accelerating factor CD55 is identified as the receptor for echovirus 7 using CELICS, a rapid immuno-focal cloning method. EMBO J. 1994;13:5070–4. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Racaniello VR. One hundred years of poliovirus pathogenesis. Virology. 2006;344:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura N, et al. Primary structure, gene organization and polypeptide expression of poliovirus RNA. Nature. 1981;291:547–53. doi: 10.1038/291547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Racaniello VR, Baltimore D. Molecular cloning of poliovirus cDNA and determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of the viral genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:4887–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson MF, Baltimore D. Polypeptide cleavages in the formation of poliovirus proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;61:77–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royston L, Tapparel C. Rhinoviruses and Respiratory Enteroviruses: Not as Simple as ABC. Viruses. 2016;8:16. doi: 10.3390/v8010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohlmann T, Jackson RJ. The properties of chimeric picornavirus IRESes show that discrimination between internal translation initiation sites is influenced by the identity of the IRES and not just the context of the AUG codon. RNA. 1999;5:764–78. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreev DE, et al. Glycyl-tRNA synthetase specifically binds to the poliovirus IRES to activate translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5602–5614. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng Z, et al. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature. 2013;496:367–371. doi: 10.1038/nature12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y-H, et al. Phosphatidylserine Vesicles Enable Efficient En Bloc Transmission of Enteroviruses. Cell. 2015;160:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richards AL, Jackson WT. Behind Closed Membranes: The Secret Lives of Picornaviruses? PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003262. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sin J, McIntyre L, Stotland A, Feuer R, Gottlieb RA. Coxsackievirus B Escapes the Infected Cell in Ejected Mitophagosomes. J Virol. 2017;91:e01347–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01347-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornell CT, Perera R, Brunner JE, Semler BL. Strand-specific RNA synthesis determinants in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus. J Virol. 2004;78:4397–407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4397-4407.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lulla V, et al. Assembly of Replication-Incompetent African Horse Sickness Virus Particles: Rational Design of Vaccines for All Serotypes. J Virol. 2016;90:7405–7414. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00548-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loughran G, Howard MT, Firth AE, Atkins JF. Avoidance of reporter assay distortions from fused dual reporters. RNA. 2017;23:1285–1289. doi: 10.1261/rna.061051.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogt DA, Ott M. Membrane Flotation Assay. Bio-protocol. 2015;5 doi: 10.21769/bioprotoc.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodfellow IG, et al. Inhibition of Coxsackie B Virus Infection by Soluble Forms of Its Receptors: Binding Affinities, Altered Particle Formation, and Competition with Cellular Receptors. J Virol. 2005;79:12016–12024. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12016-12024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingolia NT, Brar GA, Rouskin S, McGeachy AM, Weissman JS. The ribosome profiling strategy for monitoring translation in vivo by deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1534–1550. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmonds P, Welch J. Frequency and Dynamics of Recombination within Different Species of Human Enteroviruses. J Virol. 2006;80:483–493. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.483-493.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–42. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stocsits RR, Hofacker IL, Fried C, Stadler PF. Multiple sequence alignments of partially coding nucleic acid sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Firth AE. Mapping overlapping functional elements embedded within the protein-coding regions of RNA viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:12425–39. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McWilliam H, et al. Analysis Tool Web Services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W597–600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.