Abstract

Introduction:

Treatment with Positive Airway Pressure (PAP) therapy reduces injury risk among adults with OSAS, but the effect of PAP therapy on children’s injury risk is unknown. This study investigated whether treatment of OSAS with PAP reduces children’s pedestrian injury risk in a virtual reality pedestrian environment (VRPE).

Methods:

42 children ages 8–16 with OSAS were enrolled upon diagnosis by polysomnography. Children crossed a simulated street several times upon enrollment, prior to PAP treatment, and again after 3 months of PAP therapy. Children underwent sleep studies at both timepoints.

Results:

Children adherent with PAP had a significant reduction in hits by a virtual vehicle (p<.01) and less time to contact with oncoming vehicles (p<.01) following treatment. Those who were non-adherent did not show improved safety. There was no change in attention to oncoming traffic.

Conclusions:

OSAS may have significant consequences on children’s daytime functioning in a critical domain of personal safety, pedestrian skills. In pedestrian simulation, children with OSAS adherent to PAP therapy showed improvement in pedestrian safety and had fewer collisions with a virtual vehicle following treatment. Results highlight need for heightened awareness of the real-world benefits of treatment for pediatric sleep disorders.

Keywords: pedestrian safety, children, injury risk, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, PAP

Annually, 6300 American pedestrians are killed and 190,000 others are injured, and a disproportionate number of injured and killed pedestrians are children.1 Not surprisingly, prevention of pediatric pedestrian injury is targeted as a national public health priority.2 Many factors contribute to unintentional pedestrian injury. Among them are cognitive skills of the pedestrian, including reaction time, impulsivity, risk-taking, attention, and decision-making.3,5,6 These same characteristics that influence pedestrian safety are negatively influenced by sleepiness, both from sleep deprivation/insufficient sleep and from sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).7–13

OSAS is a common pediatric sleep-related breathing disorder, with estimated prevalence of 1–5% among non-obese children and 25–40% among obese children.14,15 In adults, OSAS has negative consequences on mood and behavioral regulation and also on neurocognitive functioning, including vigilance, attention, problem solving, and visual and motor functioning.16,17 Adults with OSAS are at high risk for human error and mental inefficiency, and are more likely to have inattention, risk taking, and daytime sleepiness resulting in motor vehicle crashes and occupational injury.6–8,16–18

The standard treatment for adult OSAS is positive airway pressure therapy (PAP).19–21PAP consists of patients wearing a mask interface covering the nose or nose and mouth connected to a machine by a tube. The machine blows a determined amount of pressure into the airway functioning as a “stent” to keep the airway patent. There is evidence that treatment of adult OSAS with PAP improves attention, cognitive functioning, sleepiness, and reduces the risk of motor vehicle crashes.22–25 However, the effect of PAP in children with OSAS who are not yet old enough to drive, and thus engage in traffic primarily as pedestrians, is unknown.

Pedestrian behavior, although enacted subconsciously by most adults, is a highly complex cognitive and perceptual task. A safe pedestrian must simultaneously process several pieces of information, interpret their meaning, and make a decision to cross the street when a safe opportunity arises. These tasks must occur very quickly. Impulse control, attention and reaction time are cognitive skills still developing among children that may impact pedestrian safety,3–5,26–27 and these same cognitive impairments are reported among children with untreated OSAS who engage in laboratory tasks and questionnaires.9–12,28 Thus, children with OSAS may have deficits in pedestrian safety. In fact, previous research suggests children with OSAS were at higher risk for pedestrian injury than healthy peers of the same age, race, gender, and estimated household income.29 The present study was designed to extend that result by testing whether treating OSAS may improve pedestrian safety among children with OSAS.

Specifically, we recruited children with OSAS to engage in a virtual reality pedestrian environment in two conditions: when OSAS was initially diagnosed but untreated and after OSAS was controlled for 3 months using treatment with PAP. We hypothesized children with OSAS would be safer pedestrians after adhering to treatment with PAP versus when untreated or after non-adherent treatment.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment.

Using a within-subjects design, forty-two 8- to 16-year-olds with OSAS were enrolled. Diagnosis and recruitment occurred in the Pediatric Sleep Disorders Center at Children’s of Alabama the morning following a diagnostic sleep study. All participating children met International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2 diagnostic criteria for OSAS based on diagnostic assessments that included nocturnal polysomnography (NPSG) using Sandman 9.2 technology software (Embla, Broomfield, CO) and thorough clinical evaluation from one of two attending board-certified sleep specialists early in the morning after the overnight NPSG. Standard polysomnography consisted of electroencephalogram, electromyogram, electrooculogram (right, left), arterial oxygen saturation (Sao2) oximeter pulse wave form, and end-tidal carbon dioxide tension, nasal pressure monitoring, oronasal flow using thermistor, and thoracic and abdominal wall motion. Standard pediatric scoring was used for respiratory events.30 Diagnosis of OSAS was defined as having an apnea/hypopnea index (AH) I≥1.5 per hour.31–34 All children were treated with continuous PAP (CPAP) rather than Bilevel PAP (BPAP). Exclusion criteria for the clinical sample included cognitive or physical disabilities that prevented participation in the experimental protocol (e.g., mental retardation, blindness, use of a wheelchair); comorbid medical or neurologic conditions; or antipsychotic medication use. No children were excluded.

General Procedure.

We recruited to the study children diagnosed with OSAS requiring and naïve to PAP therapy. As part of routine care, PAP was prescribed 1) after surgical intervention (tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy), follow-up sleep study determined OSAS was still present or 2) at the diagnostic study when surgical intervention was not an option (i.e., surgery was done at any point prior to initial sleep study and no regrowth of tonsillar/adenoidal tissue has occurred, persistent OSAS likely due to obesity). Following PAP prescription, an initial research visit was scheduled that included informed consent procedures and evaluation in the pedestrian virtual reality environment.

Following the initial research appointment, the family returned to the Pediatric Sleep Disorders Centers for routine care, which consisted of: 1) PAP education, 2) behavioral techniques to aid in adjusting to PAP regimen, and 3) meeting with a home durable equipment representative who fit the child for an appropriate face mask and provided the PAP machine to the family. The child practiced for 1 week to adjust to the new regimen. One week after the baseline visit, children returned to the sleep lab for an overnight sleep study to titrate their PAP to the optimal pressure according to titration manual guidelines. After 3 months of use of PAP at home, the family returned for a post treatment overnight sleep study (conducted while the child was wearing the PAP) to document use of and adequate control of OSAS with PAP and to obtain an objective check of adherence from a downloadable card housed in the machine. The morning following the final overnight visit, the family completed a second research appointment evaluating pedestrian safety in the virtual reality environment; this occurred after 3 months treatment of PAP.

Measures:

Adherence.

Our objective was to evaluate injury outcomes in participants who were adherent. Adherence was monitored with downloadable computerized usage meters in the PAP machine that document hours of usage each night. Following standard practice in the literature, the minimal criterion for category of “adherent” was greater than or equal to average of 4 hours usage per night.35–36

Sleepiness.

To verify sleepiness, we sampled level of sleepiness using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale modified for children.37 The Epworth Sleepiness Scale assesses daytime sleepiness, and is modified for children to rate the propensity to fall asleep in 8 situations in which a child may be likely to fall asleep.9 Response options are “would never doze,” slight chance of dozing,” “moderate chance of dozing,” and “high chance of dozing.” The questionnaire, originally designed for adults, is used in studies with children with OSAS with slight variations in terminology on two questions: (a) the mention of alcohol is removed in question 7 and (b) question 8 was modified to indicate the child is a passenger in a car.9

Virtual Reality Pedestrian Environment.

Details of the virtual reality pedestrian environment (VRPE), including validation data demonstrating behavior in the virtual world corresponds with behavior in real pedestrian environments among both children and adults, are available elsewhere.26 Briefly, the environment has demonstrated convergent, internal, and face validity and has been used in several studies showing impaired pedestrian behavior under a variety of conditions and situations among both children and adults.3,26,38

While participating in the virtual environment task, children stood on a wooden simulated curb and viewed the virtual pedestrian environment on three consecutive monitors arranged in a semicircle in front of them. Children were immersed in the virtual environment as they watched vehicles pass bidirectionally on the screens and heard environmental and traffic noise through speakers in the room. After deciding it was safe to cross, they stepped off the curb onto a pressure plate connected to the computer and a gender-matched avatar was then activated to cross the street. The avatar’s walking speed in the VRPE matched children’s walking speed, which was evaluated prior to the VPRE task in a separate location. If the avatar safely reached the other side, children heard one of two positive messages such as “Yes! Great job!” If the child made it across safely but was close to being hit by a car, the child heard, “Whoa! That was close!” If the child was struck by one of the cars, they heard, “Uh oh, you should try that again.” Thus, the child was immersed into a virtual world while deciding when it was safe to cross. After choosing to cross, the world became third-person, and the child witnessed the safety (or danger) of the crossing. During the experimental visits, children performed 10 practice trials to reduce learning effects and then engaged in 12 virtual street crossings. Behavior in the 12 crossings was used for analysis.

Measures of Crossing Behavior.

We considered three pedestrian outcome measures. First, we looked at overall risk of simulated injury. We also considered two aspects of crossing behavior: looking at traffic and time to contact by an oncoming vehicle after entering a traffic gap.

Simulated Injury (Collisions with Virtual Vehicles): “Hits” were any direct collisions between the virtual pedestrian and a vehicle.

Looking at traffic. To evaluate attention to traffic, looks toward traffic were tallied by head-tracking equipment (Trackir4:Pro, NaturalPoint Inc, Corvallis, OR) that monitored participants’ visual attention to traffic from the left and right. We summed the number of times participants looked left plus the number of times they looked right while waiting to cross, divided by the average wait time in seconds.

Time to contact by an oncoming vehicle: The time to contact by an oncoming vehicle was the shortest latency (in seconds) between the child and an oncoming vehicle during the time the child was in the crosswalk. Shorter time to contact by an oncoming vehicle indicates selection of a riskier traffic gap to cross within.

Data Analysis Plan.

Descriptive statistics were considered first to examine the distribution of scores and insure assumptions of inferential analyses were met. We also examined descriptively the number of children who were adherent and non-adherent to the PAP treatment. To address the primary hypothesis, that children with OSAS would engage more safely as pedestrians after adhering to treatment with PAP versus when untreated or after non-adherent treatment, we constructed mixed-model, ordinal logistic regressions run using the Generalized Estimating Equations procedure to compare pre- and post-treatment hits by simulated traffic in a stratified manner, with one model constructed among children who were adherent to PAP and a second among children who were non-adherent. Given our results that the regression was statistically significant among adherent children but not among non-adherent children, we proceeded to evaluate secondary pedestrian behavior outcomes, time to contact and attention to traffic, among only the adherent group. Paired sample t-tests compared behavior pre and post treatment among those children. All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Significance was ascribed at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Study Group

Forty-two children with OSAS were enrolled. One child was excluded who could not be provided with a machine due to inadequate insurance coverage and 12 children were lost to follow-up over the 3-month time period. Analyses comparing those lost to follow-up to those who completed the study found that children lost to follow-up were more likely to be male (92% vs 59%), but otherwise were similar on demographic, BMI, and baseline sleep measures.

Table 1 presents data for the sample of 29 children who completed the study, both overall and divided into adherent and non-adherent subgroups. Of the 29 participants, 20 children were evaluated at both visits, had usable data, and did not have persisting OSAS. One child was excluded because the downloadable card malfunctioned and eight children had persisting OSAS greater than 1.5 AHI so were categorized as inadequately treated due to poor titration. Based on the criteria of PAP usage for an average of greater than 4 hours a night, 11 of the 20 included children were adherent to the PAP therapy and 9 were non-adherent. The non-adherent group was somewhat older than the adherent group, but otherwise the two groups were similar on all variables tested.

Table 1.

Demographic, BMI, and Sleep Characteristics of Sample at Baseline

| Characteristic | Completers (N = 29) |

Adherent (N = 11) |

Non Adherent (N = 9) |

Test Statistic1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: % male | 58.6 | 54.5 | 55.6 | p = 0.658 |

| Age: mean (SD), in years | 11.9 (2.7) | 10.7 (2.2) | 14.7 (1.1) | t = 5.1** |

| Ethnicity: % white | 42.9 | 54.5 | 50.0 | p = 0.605 |

| Household Income: % Below $20,000 | 30.8 | 45.5 | 42.9 | p = 0.648 |

| ESS Total, mean (SD)2 | 12.7 (5.4) | 13.2 (5.1) | 16.4 (4.6) | t = 1.4 |

| BMI: mean (SD) (age and gender adjusted) | 36.1 (11.9) | 37.7 (11.1) | 38.4 (14.3) | F(l,16) = 0.01 |

| BMI z-score mean (SD) | 2.29 (0.16) | MED = 2.5 | MED = 2.9 | U = 26.0 |

| Polysomnography Data | ||||

| Total Sleep Time (min; mean (SD)) | 445.3 (54.2) | 455.0 (51.1) | 445.2 (27.9) | t = 0.544 |

| Sleep Efficiency % mean (SD) | 85.4 (10.6) | MED=93.6 | MED=89.9 | U = 53.5 |

| Sleep Latency (min; mean (SD)) | 16.4 (15.2) | MED=12.5 | MED=7.0 | U = 67.0 |

| Awakenings (count mean (SD)) | 24.0 (11.4) | 21.0(11.5) | 28.2 (11.7) | t = 1.4 |

| Stage 1 Sleep (%mean (SD)) | 8.0 (5.0) | 6.5 (3.9) | 10.9 (5.5) | t = 2.1 |

| Stage 2 Sleep (%mean (SD)) | 49.4 (10.0) | 48.0 (11.1) | 50.4 (10.1) | t = 0.5 |

| Stage 3 Sleep (%mean (SD)) | 23.6 (9.3) | 25.2 (10.3) | 19.7 (8.2) | t = 1.3 |

| REM sleep % mean (SD) | 18.9 (6.4) | 20.3 (6.2) | 19.0 (6.8) | t = 0.4 |

| AHI mean (SD) | 10.7 (15.0) | MED=3.0 | MED=5.7 | U = 35.5 |

Note: ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; BMI=Body Mass Index; MED=Median; AHI=Apnea-Hypopnea Index.

Test statistic compares adherent to non-adherent groups. Fisher’s exact test p values presented for categorical variables. Independent samples t or Mann Whitney U statistics presented for continuous variables, depending on distribution of outcome variable. ANCOVA used for BMI in order to covary age and gender.

N=10 for adherent group and N=8 for non-adherent group on this variable due to missing data.

p < .05.

p < .01.

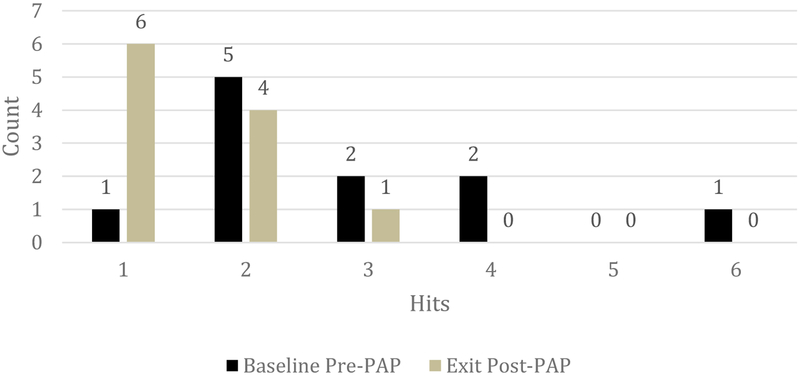

To test the primary hypothesis, stratified mixed model, ordinal logistic regression analyses indicated that following treatment, children adherent and adequately treated with PAP experienced a significant reduction in hits by simulated vehicles in the VRPE (Wald χ2(1) = 6.86, p=.009, Figure 1) but children not adherent to treatment with PAP did not experience a significant reduction in hits by simulated vehicles (Wald χ2(1) = 1.47, p=.23). A follow-up mixed binomial regression indicated that, when untreated, children were 12 times more likely to have a simulated hit by a virtual vehicle than when adherent to PAP (Wald χ2(1) = 5.61, OR 12.00, 95% CI 1.12 – 128.84, p=.018).

Figure 1.

Reduction in Hits by a Virtual Vehicle in Children with OSAS Adherent to PAP

Given these results, we next examined secondary pedestrian safety outcomes at baseline and post-treatment among children adherent to treatment. As shown in Table 2, children adherent to treatment showed a significant improvement in time to contact with oncoming vehicles post-treatment (t(10) = 4.05, p < 0.01), indicating they had left more time between themselves and oncoming traffic following treatment. There was not a significant change post-treatment in looking at oncoming traffic (t(10) = −.63, p = 0.55).

Table 2.

Pedestrian Outcome Measures in Children with OSAS adherent to PAP

| Pedestrian Risk Outcome Measure |

Pre M (SD) |

Post M (SD) |

t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time To Contact | 3.45 (0.61) | 4.43 (0.68) | 4.05 | 10 | 0.002 |

| Looking At Traffic | 27.60 (9.97) | 30.27 (8.54) | 0.63 | 10 | 0.546 |

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest children with OSAS who were treated with PAP therapy experienced significant improvement in their pedestrian safety, as measured in a virtual pedestrian environment, following adherence to PAP therapy. In contrast to children who were not adherent, we found adherent children experienced a significant reduction in collisions with virtual vehicles. We also saw an improvement in leaving more time before contact with oncoming traffic among adherent children.

Results reinforce the fact that pediatric OSAS causes significant cognitive impairment that manifests itself in multiple applied domains, including pedestrian safety, and that adherent treatment with PAP therapy can produce positive change in functioning. Crossing streets safely requires simultaneous processing of several pieces of information, and therefore is a highly complex cognitive and perceptual task. OSAS may impair relevant cognitive components.28 When children with OSAS were adherent to PAP, they seemed to re-gain cognitive capacity and engaged more safely in the virtual street environment, functioning closer to what their age and development status would predict. When they were untreated at baseline, their pedestrian safety was compromised.

Consistent with other research, we did not find that looking at traffic was impaired or improved with PAP therapy.29,39 A possible explanation for this finding is that when they are sleepy, children are still able to follow simple and rote rules learned when they were young, such as looking both ways before crossing, but they may not fully process cognitively the complex environment they perceive or select safe traffic gaps to cross within. This hypothesis corresponds with results from research investigating pedestrian safety in untreated pediatric sleep disorders of central hypersomnia and untreated OSAS, in which children looked both ways at traffic but did not process the crossing properly and were struck by virtual vehicles.29,39

Our findings have implications for clinical practice. While a few pediatric studies have documented cognitive improvement on laboratory tasks following PAP therapy,40–42 this study extends findings to the applied outcome of unintentional pedestrian injury risk. In adults with OSAS, PAP therapy improves occupational safety, driving performance, and injury risk following PAP therapy.22–24 This study offers initial evidence that pediatric functioning concords with that of adults and PAP therapy has the potential to reduce injury risk among children engaging in what is perhaps the most common mode of transportation where children influence their own safety, pedestrian injury.

We note several study limitations. First, we recruited children with OSAS from a clinically referred group of children that may represent a group with more severe symptoms that prompt a referral than the larger community sample of children with OSAS. Second, while we chose 3 months as an outcome point based on prior research,41–42 the minimal amount of daily PAP use required for improvement in safety and the length of time needed to wear PAP before safety improvement is observed remain unknown. Third, our study suffered from attrition over the three-month time period. Fourth, we used a non-counter-balanced within-subjects research design. Ethical considerations prohibited counterbalancing or inclusion of a clinical control group, but future research might consider alternative research designs to control for the possibility of practice effects and the simple cognitive-perceptual development that occurs in children over a 3-month time period and might influence pedestrian behavior and skill. Finally, the findings are limited to pedestrian injury. Future research should consider other aspects of health and safety among children with OSAS, other treatments that might reduce injury risk in children with OSAS, and possible countermeasures that could be implemented to promote increased safety.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Carole L. Marcus for her guidance as a consultant on the initial study design and Anna Johnston, research coordinator for the UAB Youth Safety Lab. We thank Digital Artefacts for their development and support of the virtual reality system.

Acknowledgement of Funding Source: The project was supported primarily by the RESMED Foundation and also by Award Number R01HD058573 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, or RESMED foundation.

Financial Disclosure: KTA received support from RESMED foundation. All data collection, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing were performed by the investigators independent of RESMED foundation. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- OSAS

obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- PAP

positive airway pressure

- VRPE

virtual reality pedestrian environment

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). WISQARS™ (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System). Retrieved 7/18/18 from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- 2.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2018). Pedestrian Safety. Retrieved 7/18/18 from https://www.nhtsa.gov/road-safety/pedestrian-safety

- 3.Schwebel DC, Gaines J, Severson J. Validation of virtual reality as a tool to understand and prevent child pedestrian injury. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:1394–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwebel DC, Barton BK. Contributions of multiple risk factors to child injury. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(7):553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson JA, Tolmie AK, Foot HC, Sarvary PH, Whelan KM. Influence of virtual reality on the roadside crossing judgments of child pedestrians. J Experim Psych: Applied 2005;11(3):175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinges DF. An overview of sleepiness and accidents. J Sleep Research. 1995;4: 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Findley L. Vigilance and automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Chest. 1995;108(3):619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Thoracic Society: Sleep apnea, sleepiness, and driving risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;50:1463–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melendres MC, Lutz JM, Rubin ED, Marcus CL. Daytime sleepiness and hyperactivity in children suspected with sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics. 2004;114:768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beebe DW, Groesz L, Wells C et al. The neuropsychological effects of obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis of norm referenced and case controlled data. Sleep. 2003;26(3):298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beebe DW, Wells CT, Jeffries J, Chini B, Kalra M, Amin R. Neuropsychological effects of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(7):962–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beebe DW. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. SLEEP 2006;29(9):1115–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redline S, Tishler PV, Schluchter M, Aylor J, Clark K, Graham G. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children. Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1527–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus CL, Brooks LJ, Ward SD et al. Diagnosis and management of childhood Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics 2012;130:1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso-Alvarez ML, Cordero-Guevara JA, Teran-Santos J, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in obese community-dwelling children: the NANOS study. SLEEP 2014;37:943–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal C, Strange C, Bachman D. Neurocognitive impairment in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2012;14:1601–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treager S, Reston J, Schoelles K, Phillips B. Obstructive sleep apnea and risk of motor vehicle crash. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5:573–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aksan N, Marini R, Tippin J, et al. Driving performance and driver state in obstructive sleep apnea: What changes with positive airway pressure? Proc Int Driv Symp Hum Factors Driv Assess Train Veh Des 2017;9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gay P, Weaver T, Loube D, Iber C. Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep related breathing disorders in adults. SLEEP 2006;29:381–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgenthaler TI; Kapen S; Lee-Chiong T et al. Practice parameters for the medical therapy of obstructive sleep apnea. SLEEP 2006;29(8):1031–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kushida CA, Littner MR, Hirshkowitz M et al. Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. SLEEP 2006;29:375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tregear TS, Reston J, Schoelles K, Phillips B. Continous positive airway pressure reduces risk of motor vehicle crash among drivers with obstructive sleep apnea. SLEEP 2010;33(10):1373–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George CF. Reduction in motor vehicle collisions following treatment of sleep apnea with nasal CPAP. Thorax 2001;56:508–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Findley L, Smith C, Hooper J, Dineen M, Surratt PM. Treatment with nasal CPAP decreases automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:857–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez AI, Martinez P, Miro E, Bardwell WA, Buela-Casal G. CPAP and behavioral therapies in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: effects on daytime sleepiness, mood, and cognitive function. Sleep Med Rev 2009;13:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwebel DC, Davis AL, O’Neal EE. Child pedestrian injury: A review of behavioral risks and preventive strategies. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2012;6(4):292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barton BK. Integrating selective attention into developmental pedestrian safety research. Canad Psych 2006;47:203–210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardoso TSG, Pompeia S, Miranda MC. Cognitive and behavioral effects of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: A systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine 2018;46:46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avis K, Gamble KL, Schwebel DC. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome increases pedestrian injury risk in children. J Pediatr 2015;16:109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed.: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry RB; Budhiraja R; Gottlieb DJ; et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8(5):597–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witmans MB, Keens TG, Davidson Ward SL, Marcus CL. Obstructive hypopneas in children and adolescents: normal values. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Traeger N, Schultz B, Pollock AN, Mason T, Marcus CL, Arens R. Polysomnographic values in children 2–9 years old: additional data and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol 2005;40: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uliel S, Tauman R, Greenfeld M, Sivan Y. Normal polysomnographic respiratory values in children and adolescents. Chest 2004;125:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King MS, Xanthopoulos MS, Marcus CL. Improving Positive Airway Pressure in Children. Sleep Med Clin 2014;9: 219–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pepin JL, Krieger J, Rodenstein D, et al. Effective compliance during the first 3 months of continuous positive airway pressure. A European prospective study of 121 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johns MW. A New method for measuring daytime sleepiness; the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stavrinos D, Biasini FJ, Fine PR, Hodgens JB, Khatri S, Mrug S, Schwebel DC. Mediating factors associated with pedestrian injury in children with attention-deficit disorder. Pediatrics 2011;128(2):296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avis KT, Gamble KL, Schwebel DC. Does excessive daytime sleepiness affect children’s pedestrian safety? SLEEP 2014;37(2):283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcus CL, Rosen G, Ward SL, Halbower AV, Sterni L et al. Adherence to and effectiveness of positive airway pressure therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics 2006;117;e442–e451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcus CL, Radcliffe J, Konstantinopoulou S, Beck S, Cornaglia M et al. Effects of positive airway pressure therapy on neurobehavioral outcomes in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:998–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beebe DW, Byars KC. Adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea adhere poorly to positive airway pressure (PAP) but users show improved attention and school performance. PLos ONE 2011;6(3):e16924.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]