Abstract

Much research on cohabitation focuses on transitions from cohabitation to marriage or dissolution, but less is known about how rapidly women progress into cohabitation, what factors are associated with the tempo to shared living, and whether the timing into cohabitation is associated with subsequent marital transitions. We use data from the 2006–2013 National Survey of Family Growth to answer these questions among women whose most recent sexual relationship began within 10 years of the interview. Life table results indicate that transitions into cohabitation are most common early on in sexual relationships; nearly one quarter of women had begun cohabiting within six months of becoming sexually involved. Multivariate analyses reveal important social class disparities in the timing to cohabitation. Not only are women from more advantaged backgrounds significantly less likely to cohabit, but those who do enter shared living at significantly slower tempos than do women whose mothers lacked a college degree. In addition, among sexual relationships that transitioned into cohabiting unions, college-educated women were significantly more likely to transition into marriage than less-educated women. Finally, though the tempo effect is only weakly significant, women who moved in within the first year of their sexual relationship demonstrated lower odds of marrying than did women who deferred cohabiting for over a year. Relationship processes are diverging by social class, contributing to inequality between more and less advantaged young adults.

Keywords: Cohabitation, marriage, tempo, relationship progression, young adults

Relationship formation, particularly when accompanied by non-marital parenting, has emerged as a topic of academic and policy interest (Glenn 2002; Hymowitz, Carroll, Wilcox, and Kaye 2013; Sawhill 2014; Stanley, Rhoades, and Markman 2006). Some argue that contemporary young adults are drifting into sexual relationships and shared living without adequate commitment to their partners (Sawhill 2014; Stanley et al. 2006). Various studies suggest that rapid relationship progression reduces dedication, is associated with lower marital quality (should couples wed), and adversely affects parenting (Cherlin 2009; Glenn 2002; Sassler, Addo, and Lichter 2012; Stanley, Rhoades, and Whitton 2010). To date, however, little is known about how rapidly relationships progress, or if this tempo is associated with subsequent union transitions.

As of the early years of the 21st century, over half of young American adults had ever cohabited, and the majority of those who married first lived with their partners (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). The basic facts about contemporary union formation – what proportions of adults cohabit or marry, how that varies by age, race, and educational attainment, and shifts in the factors conditioning transitions from cohabitation into marriage – are well known (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008; Lichter, Qian, and Mellott 2006; Manning, Brown, and Payne 2014). Less often studied is how rapidly sexual relationships transition into cohabitation or marriage, or from cohabitation to marriage. This omission is curious, given evidence showing growing social class divergence in how relationships progress. Even as cohabitation has become more common across all social classes, it remains most prevalent among the economically disadvantaged and moderately educated (Guzzo 2014; Lichter, Turner, and Sassler 2010; Manning et al., 2014; Sassler and Miller, 2017). Marriage, in contrast, has become increasingly selective of the economically advantaged (Goldstein and Kenney 2001; Lichter et al. 2006; McLanahan 2004). Yet the majority of those who wed have lived with their partners before the marriage (Manning 2013), raising the question of whether cohabitation operates in the same way for more and less advantaged individuals. A better understanding of the factors that expedite or delay the transition of sexual relationships into cohabitation or direct marriage, and from cohabitation to marriage, is needed.

In this article, we use data on young women’s most recent sexual relationships (including those that are current at the time of the interview) from the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) to build on previous work in three important ways. Our primary objective is to determine whether the timing to cohabitation is associated with the tempo to marriage among women whose most recent relationship involved a cohabitation spell. To answer this question, we first provide estimates of the timing from sexual involvement to cohabitation and marriage for women’s most recent sexual relationship, using multiple-decrement life table techniques. Second, we update previous studies that explored the factors shaping the transition into either cohabitation or marriage. Third, among those women who first transition into cohabitation, we assess whether the timing to cohabitation is associated with the tempo to marriage. Our results shed additional light on the role cohabitation plays in the increasingly divergent family behaviors of those from more and less privileged backgrounds.

Research on the Tempo of Relationship Progression

Family scholars have increasingly stressed the need to pay closer attention to how relationships unfold (Cherlin 2009; McLanahan 2004; Sassler 2010). Premarital sexual involvement has been normative for several generations. Among cohorts of women turning 15 between 1964 and 1993, at least 86% had premarital sex by age 25 (Finer 2007). Furthermore, two-thirds of women entering first marriages in the early years of the 21st century cohabited with their partner prior to the wedding (Manning 2013). Much attention has focused on aspects of sexual experience – including age at sexual debut, number of sexual partners, and cohabitation experience – but less attention has been paid to how rapidly sexual relationships transition into shared living, whether via cohabitation or marriage, and whether the tempo to cohabitation shapes subsequent transitions into marriage.

Data limitations have largely prevented researchers from distinguishing among respondents with different patterns of sexual relationship progression (Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2013). While numerous studies explore the timing from cohabitation to marriage (Brown 2000; Lichter et al. 2006; Sassler and McNally 2003), or childbearing to marriage (Carlson, McLanahan, and England 2004; Harknett and Kuperberg 2011), to our knowledge, only two published papers have addressed the sequencing of different stages of sexual relationships. Using data from married couples in a nationally representative internet survey conducted in 2010 for the National Center for Family and Marriage Research (NCFMR) by Knowledge Networks, Halpern-Meekin and Tach (2013) explored the impact of relationship progression on relationship quality, examining discordance in couples’ retrospective reporting of premarital relationship stages. Women who cohabited prior to marriage reported spending an average of 11 months dating before they began to spend the night together, compared with almost 24 months for women who married without cohabiting.1 Among women who cohabited, the transition from spending the night to living together was rapid, about 3 months, but the tempo from shared living to marriage considerably slower, almost 22 months (Halpern-Meekin and Tach 2013, Table 2).2 No information was presented about whether tempos varied by social class, race, or parental status at the time of the relationship’s start.

Table 2.

Multiple-Decrement Life Table Estimates of Transitions from Sexual Relationships

| Panel A: Full Sample | Months Since Start of Sexual Relationship |

|||||||

| Outcome | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 |

| Still Sexually Involved | 0.826 | 0.740 | 0.671 | 0.611 | 0.501 | 0.418 | 0.352 | 0.289 |

| Entered Cohabiting Union | 0.151 | 0.226 | 0.283 | 0.330 | 0.417 | 0.473 | 0.518 | 0.560 |

| Entered Marriage | 0.023 | 0.034 | 0.046 | 0.059 | 0.082 | 0.108 | 0.130 | 0.151 |

| N = 6,086 | ||||||||

| Months Since Start of Cohabitationa | ||||||||

| Panel B: Cohabitors | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 |

| Entered Marriage | 0.036 | 0.080 | 0.126 | 0.162 | 0.240 | 0.327 | 0.389 | 0.442 |

| Still Cohabiting/Broke up | 0.964 | 0.920 | 0.874 | 0.838 | 0.760 | 0.673 | 0.611 | 0.558 |

| N = 2,831 | ||||||||

Source: 2006–10 and 2011–13 NSFG Female respondent file. Women between the ages of 18-

Note: Individuals who break up are considered censored after the break-up date.

Among those who entered a cohabiting union, 52% marry within 4 years, 59% marry within 5 years, 64% marry within 6 years, 68% marry within 7 years, and 72% marry within 8 years

The second published study concentrated more specifically on relationship tempos. Focusing on young adults (18 to 24), Sassler and Joyner (2011) explored whether racially heterogamous couples proceeded more rapidly into sexual intimacy and from sex to cohabitation, marriage, or dissolution, than homogamous couples. The paper provided detailed information on the distribution of timing into sexual involvement using data from the 2002 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Sassler and Joyner, 2011, Table 2), and from sexual involvement to marriage, cohabitation, or dissolution (using Add Health and the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth data). Although the largest proportion of women involved in sexual relationships subsequently progressed into cohabiting unions, the paper did not present survival estimates of the timing from sexual involvement to marriage, or from cohabitation to marriage (Sassler and Joyner 2011, Table 3). The results indicated that minority women with white partners progressed significantly more rapidly into cohabitation than did women in racially homogamous unions, or white women partnered with minority men. The relative youth of the sample, however, resulted in too few events to examine transitions from cohabitation to marriage or dissolution. Utilizing more recent data from the NSFG, Sassler and colleagues examined how rapidly sexual relationships formed in the prior year progressed into cohabiting unions or dissolutions (Sassler, Michelmore, and Holland 2016), though given the short window they were unable to explore subsequent transitions. Nonetheless, they reported that indicators of social class disadvantage expedited transitions into cohabitation.

Table 3.

Relative risk ratios from multinomial logistic regression models predicting likelihood of cohabiting or marrying, as a function of duration since first sex (in months): women aged 18–44 whose relationship began within 10 years of the interview

| Model A |

Model B |

Model C |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. no coresidential union | vs. no coresidential union | vs. no coresidential union | ||||

| Duration of relationship since first sex (months) | ||||||

| <6 months | 1.491 *** | 0.897 | 1.478 *** | 0.880 | 1.448 ** | 0.879 |

| 7–12 months | 1.077 | 1.067 | 1.073 | 1.067 | 1.044 | 1.017 |

| 13–18 months (reference) | ||||||

| 19–24 months | 0.878 | 1.382 | 0.885 | 1.395 | 0.904 | 1.479 |

| 25–30 months | 0.728 † | 0.985 | 0.735 † | 1.015 | 0.765 | 1.116 |

| 31–36 months | 0.744 † | 0.898 | 0.756 † | 0.955 | 0.787 | 1.059 |

| >36 months | 0.487 *** | 1.053 | 0.502 *** | 1.227 | 0.520 *** | 1.548 † |

| Background characteristics | ||||||

| Family structure at age 14 (Ref = Lived with both parents) | ||||||

| Lived with single parent | 0.965 | 0.466 ** | 1.074 | 0.709 | ||

| Lived with step parent | 1.171 † | 0.644 * | 1.179 † | 0.896 | ||

| Lived with no biological parent | 1.009 | 1.008 | 1.091 | 1.476 | ||

| Parents not married at the time of birth | 0.700 *** | 0.347 *** | 0.879 | 0.445 ** | ||

| Mother’s education (Ref = High school degree) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 1.015 | 1.661 * | 1.039 | 1.721 * | ||

| Some college | 1.052 | 0.933 | 1.060 | 0.990 | ||

| College degree | 0.833 * | 1.304 | 0.823 * | 1.366 | ||

| Respondent completed HS by relationship start | 1.017 | 1.504 * | 0.894 | 1.054 | ||

| Race (Ref = Non-Hispanic white) | ||||||

| Black | 0.442 *** | 0.530 * | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.871 | 0.764 | ||||

| Other | 0.967 | 1.582 | ||||

| Relationship history | ||||||

| Age at first sex with most recent partner (Ref=21–24 years old) | ||||||

| <18 | 0.676 ** | 0.331 *** | ||||

| 18–20 | 0.847 † | 0.675 * | ||||

| 25–29 | 1.173 † | 1.260 | ||||

| 30+ | 0.662 ** | 1.398 | ||||

| Year of relationship start (Ref :1996–2000) | ||||||

| 2001–2003 | 1.005 | 1.114 | ||||

| 2004–2006 | 0.895 | 0.731 † | ||||

| 2007–2009 | 0.789 * | 0.732 | ||||

| 2010–2012 | 0.912 | 0.924 | ||||

| Other Relationship Experience | ||||||

| Number of Sexual Partners | 1.005 | 0.871 *** | ||||

| Respondent had prior cohabiting unions | 0.959 | 0.294 *** | ||||

| Respondent had a child prior to current union | 0.790 * | 0.488 † | ||||

| Respondent is pregnant (time-varying) | 2.034 *** | 3.024 *** | ||||

| df | 4 | 26 | 54 | |||

| Number of Observations | 113,834 | 113,834 | 113,834 | |||

Source: 2006–10 NSFG Female respondent file. Women between the ages of 18–44. Note: Current cohabitors, former cohabitors, and married couples who first cohabited are all considered cohabiting. Those who married directly are in the married category. Non-residential sexual relationships serve as the reference group. Underlined terms indicate significant differences between cohabiting and marrying at the p ≤ .05 level.

Note:

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

Excludes women who had previously been married

Qualitative researchers have also sought clarification on how relationships progress, with an emphasis on transitions into cohabitation. Several studies suggest that entry into cohabitation occurs gradually. Jamison and Ganong (2011) interviewed college-educated daters (n = 22), and described how respondents gradually began spending nights together over time (stayovers, in their terminology), progressively increasing the number of nights. Manning and Smock (2005) drew on interviews with a diverse sample of 115 young adults with current and past cohabitation experience, and found that couples reported spending more and more nights together with increasing relationship duration. But Sassler (2004; Sassler and Miller 2011, 2017) noted social class differences in the tempo of relationship progression; these studies were based on two class-diverse samples, one of cohabiting individuals in New York City (n = 30), and the second of cohabiting couples in Columbus, Ohio (n = 122). Among those with a high school degree or post-secondary schooling but no Bachelor’s degree, half began cohabiting within six months of the relationships start. The college educated, in contrast, were romantically and sexually involved for longer periods (on average a year) before moving into shared living (Sassler and Miller 2011), consistent with Jamison and Ganong (2011). Highly educated couples also more frequently reported concrete marriage plans than their less educated counterparts, suggesting that their transition from cohabitation into marriage occurred more rapidly (Sassler and Miller 2011, 2017). Qualitative studies, with their small sample sizes, are not adequate to explore population level associations, but their findings highlight the need to further examine variation in sexual relationship progression.

Explanations for Variation in Relationship Tempos and Transitions

Social class of one’s family of origin, race, and occupational and educational pursuits shape young adult’s life course trajectories in important ways. Much of the research on transitions into cohabitation or marriage, or from cohabitation to marriage or dissolution, has focused on individual level economic determinants of union formation, such as whether school enrollment, educational attainment, or employment and earnings shape transitions into cohabitation or marriage (for a review, see Smock, Manning, and Porter 2005). Early studies of transitions into cohabitation or marriage often included controls for family background (e.g., Carlson, McLanahan, and England 2004; Clarkberg 1999; Manning and Smock 1995; Thornton 1991), but did not focus extensively on social class differences in relationship processes.

In recent years, greater attention to the diverging destinies experienced by youth from more and less privileged social class backgrounds has highlighted this research gap (Lichter et al. 2006; McLanahan 2004). A growing body of literature explores how the social class of youth’s family of origin shapes adolescent and young adult romantic relationships. Youth from less advantaged backgrounds often enter into sexual relationships at younger ages and engage in more relationships than do young adults from more privileged family backgrounds (Cavanagh 2007; Cavanagh, Crissey, Raley 2008; Pearson, Muller, and Frisco 2006; Sandberg-Thomas and Dush 2014). We hypothesize that social class also influences the tempo of entering into shared living, and that this may be associated with subsequent union transitions. We operationalize social class of family of origin in terms of family structure through adolescence, maternal marital status at birth, and maternal educational attainment, as together these indicators represent the relative social and economic position of families in the United States (Lareau 2003; McLanahan 2004).

Economic disadvantage among the parental generation affects young adults’ relationship experiences in various ways (Amato 2005; Cherlin 1995; Graefe and Lichter 1999; McLanahan 2004). Disadvantaged status is frequently transmitted across the generations; women who grew up in poor families engage in partnering and parenting at younger ages than their more advantaged counterparts (Amato 2005; Cavanagh et al. 2008; Cooksey, Mott, and Neubauer 2002; Pearson et al. 2006; Sassler et al. 2016). Children from single- or step-parent families also receive less financial support to achieve academically than do those from intact married-parent families (Astone and McLanahan 1991; Ermisch and Francesconi 2001). Though experiencing family disruption or parental repartnering accelerates young adults’ departure from the parental home (Aquilino 1991; Cherlin 1995; Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1998; Teachman 2003), youth from economically disadvantaged backgrounds often lack the resources necessary to maintain independent households, perhaps due to low paying jobs or the absence of parental assistance for residential autonomy (Sassler and Miller 2011). Those growing up in middle class families, in contrast, are often encouraged to delay forming serious relationships until later in the life course (Cavanagh 2011). Youth born to highly educated mothers are expected to attend and complete college prior to embarking on intimate coresidential relationships (Furstenberg 2008; Lareau 2003). Though they may not defer sexual relationships, the evidence suggests that they maintain separate homes during the early stages of dating (Jamison and Ganong 2011; Sassler and Miller 2011), perhaps because they receive parental assistance in paying for schooling and housing (Rindfuss and VandenHeuval 1990).

Extending the literature on variation in transitions into cohabitation versus marriage, we anticipate that indicators of economic disadvantage will not only increase the odds of entering into cohabitation versus marriage, but will expedite transitions from sexual relationships into cohabitations while deterring marriage. Markers of family advantage, in contrast, are expected to delay entrance into cohabiting unions. Research highlights that youth from more advantaged social class backgrounds are more likely to marry directly, but whether they also experience more rapid transitions from sexual relationships into marriage is unclear, given the lengthy process of acquiring educational and occupational credentials needed for transmission of middle class status.

Markers of advantage have also been found to elevate the likelihood of marriage among cohabitors; cohabiting women who have completed college are significantly more likely to marry than are less educated women (Lichter et al. 2006). The qualitative research on cohabitors also finds that less advantaged cohabitors often stress that particular factors, such as completing school, obtaining stable employment, or paying off loans, must be in place before a marriage can ensue (Sassler and Miller 2011; Smock, Manning, and Porter 2005). We therefore expect that, conditional on cohabiting, more advantaged women will be more likely to transition into marriage, and will do so more rapidly, than will their less advantaged peers.

DATA AND METHODS

Data

Data come from the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth, an ongoing nationally representative cross-sectional sample of men and women between the ages of 15 and 44. A unique strength of the NSFG is its collection of information on the month and year that the respondent and her most recent sexual partner first had sexual intercourse, so long as the partner was either current as of the interview date, or the relationship ended within the 12 months prior to the interview date. The overwhelming majority of women report being in a sexual relationship in the past 12 months.3 We limit our sample to those women whose most recent or current sexual relationship began within ten years of the interview, 10,045 women from the 2006–10 and 4,588 women from the 2011–13 NSFG. We use the date of first sexual intercourse as the starting point for the relationship. Dates were also obtained for the month and year respondents began living with their partner 4 and married.

Of the 14,633 women aged 18 to 44 years old in the combined 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 NSFG whose sexual relationship began within ten years of the interview date, we restricted our analysis to women who fell into one of the following categories: 1) currently dating someone but not coresiding; 2) currently cohabiting with a partner; 3) currently married; or 4) separated within the last 12 months from their most recent partner and not yet in a new sexual relationship (n=12,681). We excluded 1,057 women who had been married previously, as retrospective recall bias is lower for first marriages (Bumpass and Lu 2000; Kuo and Raley 2016). Also excluded were 587 women who had not ever had sex prior to moving in with their partners, and another 225 women who were missing information on the date of move-in or who reported dates that resulted in a negative duration between the date of first sex with the most recent partner and the date of move-in.5 Finally, we eliminated 122 women who had missing information for their mother’s educational attainment, a key covariate in our analysis.

Our final sample contained 6,086 women whose most recent or current sexual relationship had started within 10 years of their survey date and who were between the ages of 18 and 44 at the time of the interview: 545 women who married directly and were still with that partner, 2,831 women who had entered into a cohabiting union, and 2,710 women who were sexually involved but did not enter into shared living with their partner. For the second stage of our analysis we limited our sample to the 2,831 women whose most recent sexual relationship involved a cohabiting union, and explored whether their unions transitioned into marriage (n = 1,158). Even though our ten-year time frame surpasses the five year duration utilized by others (Bumpass and Lu 2000; Hayford and Morgan 2008; Kuo and Raley 2016), these studies began their clock when respondents began cohabitating, rather than when the sexual relationship started. A five year window simply does not provide enough observations of transitions from sexual involvement into cohabitation and then to marriage. 6 We employ life table methods and event history analysis to control for the start year and duration of current or most recent sexual relationships.

Analysis

Multiple-decrement life table estimates

We first provide life table estimates of transitions of respondents’ most recent sexual relationships into coresidential unions, distinguishing between direct marriage and cohabitation. Multiple-decrement life tables are used to estimate the likelihood of cohabitation or marriage (Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot 2001). The cumulative proportion of women entering cohabitation or marriage within 3 years of initiating the sexual relationship are presented. Relationships that we do not observe transitioning into cohabitation or marriage during this window are censored at the interview date or the break up (the date of last sex), whichever comes first. Next, we examine life table estimates of transitions out of cohabiting unions to estimate the likelihood of marriage, presenting the cumulative proportion of women marrying within 3 years of moving in together, censoring at the interview date or the break up.

Event-history analysis.

We next fit discrete-time event history models that examine various relationship progression stages. Our first analysis examines transitions out of sexual relationships, treating entrance into cohabitation or marriage as competing risks relative to continuance in sexually intimate non-cohabiting relationships. As the data are measured in months, our approach is quite similar to a continuous-time hazard model (Allison 1984; Kalbfleisch & Prentice 2002). Respondents contribute person-months to the data until they experience an event, either marriage or cohabitation, or are censored (either at the interview date or the break up). Our second analysis limits the sample to women whose most recent relationship involved a cohabiting union, and examines transitions to marriage. We assume that our outcomes are distinct events influenced by different underlying mechanisms (Allison 1984).

Our first model takes the following functional form:

Where Pijt is the conditional probability of experiencing direct marriage or cohabitation (j=1 for cohabitation or j=2 for marriage; j=0 for censored cases) for woman i at year t since the start of the sexual relationship, given that she has not yet experienced an event or been censored prior to year t. aij is a set of dummy variables to control for time dependence (in six-month increments). We explored various measures of duration to ascertain temporal patterns and chose the interval measure as it captured the time effect more accurately and had the best model fit.7 We include a set of M time-constant variables as well as N time-varying variables (measured at time t-1).

Our second model takes a logistic regression form, where Pit is the conditional probability of experiencing a marriage for a cohabiting woman i at month t since the start of the cohabitation, given that she has not yet experienced an event or been censored prior to month t. Here, we model duration since cohabitation date as a quadratic, as this model provided the best fit over other models that specified the duration in six-month or twelve-month intervals. Our primary independent variables of interest (described below) are time-constant, but we also include some time-varying control variables.

Independent Variables: Social Class Measures

Our key independent variables are proxies of social class, measured by respondents’ childhood family characteristics. Family structure is measured with dummy variables for whether respondents always lived with biological or adoptive parents (the reference) or ever lived with a single mother, a stepfather, or with no biological parents. We also assessed the educational attainment of the respondent’s mother, determining whether she had less than a high school degree, some post-secondary education but no degree, or a college degree or more, with a high school education serving as the reference category. Another measure indicated whether respondents’ parents were married at their birth (Married = 0, unmarried = 1). Last, we determine whether the respondent had completed high school at the start of the sexual relationship. Other indicators (the age of the respondent’s mother at her birth, the respondent’s number of siblings) were tested but not included, as they never reached conventional levels of statistical significance.

Our second analysis, which is limited to those whose most recent relationship transitioned into cohabitation, includes family structure during childhood, though we omitted our indicators of maternal education and maternal marital status at birth, as they never reached conventional levels of significance. Our measure of social class now includes information about the respondents’ own education at the time they began cohabiting, to reduce concerns of endogeneity of educational attainment to cohabitation and marriage decisions. This is an imperfect measure; pursuing post-secondary education has become increasingly protracted (Bound, Turner, and Lovenheim 2012), and many of our respondents were young and may obtain additional schooling and, possibly, degrees after the cohabitation date. The NSFG data on school enrollment, however, is not detailed enough to enable time-varying measures of school attendance and completion. Nonetheless, a large proportion of our respondents (71%) had finished their education prior to entering their cohabiting union. We therefore examine respondents’ own educational attainment as a social class indicator of transitions from cohabitation into marriage, comparing respondents with some post-secondary schooling but no degree (the reference category) to those with less than a high school degree, a high school diploma, or a college degree (or more). Respondents who did not have a high school degree at the time of the interview, or reported that the high school degree date was after the move-in date, were coded as having less than a high school degree. They were classified as high school graduates if their highest degree as of the interview date was a high school diploma. Women who reported having some post-secondary schooling at the time of their interview, or who completed their college degree after the move-in date, were classified as having some college education. Finally, respondents were considered college graduates if their college graduation date was prior to the move-in date.

Other Controls

Other background measures include the respondents’ race and ethnicity, categorized as Non-Hispanic white (the reference), black, Hispanic, and other. We include dummies to determine how old the respondent was at the start of her most recent sexual relationship: less than 18, between 18 and 20, 21 and 24 years, 25 to 29, or 30 or older. We also include a measure of when the relationship began, from 2001–2003, 2004–2006, 2007–2009, 2010 to 2012; relationships formed between 1996 and 2000 served as the reference group. These controls address concerns of recall bias that may be introduced by including relationships formed up to 10 years prior to the interview date. Our last measures account for respondents’ sexual and relationship histories. We include a continuous measure of the number of prior sexual partners, top-coded at 20 partners (which represented the 99th percentile), as well as several dichotomous indicators of whether the respondent had ever cohabited with another partner, or was a parent at the start of the most recent sexual relationship (1 = yes for all measures). Our final measure is a lagged time-varying indicator of whether the respondent was pregnant (1 = yes).

Most of the same measures are utilized in our second analysis, with a few exceptions. We constructed a measure of the time to shared living. Of those who entered into a cohabiting union, over half (59%) had moved in with their partner within a year of starting their sexual relationships, consistent with the findings of some qualitative studies (Sassler 2004; Sassler and Miller 2011). By the end of the second year of sexual involvement, over three-quarters of respondents who entered a cohabiting union (78%) had moved in with their partner.8 We therefore created a dummy variable indicating those who entered their cohabiting union within the first year of their relationship; those who deferred cohabiting for a year or longer serve as the reference group. We also specify the month since the respondents began their cohabiting union, utilizing a linear and quadratic term, as preliminary results suggested a non-linear relationship between time cohabiting and marriage. Our last new measure introduces a linear term for the year the cohabiting union began (which spans from 1996 through 2012).

All means for the descriptive analyses rely on NSFG person weights estimated for the entire sample; our multivariate models are also weighted using the NSFG person weights. Means are presented in Table 1. A sizable proportion of our respondents experienced some form of family disadvantage. Less than two-thirds of the women had grown up in intact, married-parent families (Column A), and similar proportions had grown up with either a low educated mother or a college educated one (18.9% vs. 21.4%). But those who married directly (Column B) differ from women who cohabited (Column C), as well as from women in a non-residential sexual relationship (Column D). Over three-quarters of those who married directly grew up in an intact family, compared with lower proportions of both other groups of women. Direct marriages were more likely to occur among those with college-educated mothers and who had a college degree themselves. Compared to those who formed cohabiting unions or were dating but not coresiding with their partners, women who married directly were older, on average, at the time of their interview and their relationships more often had begun in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Women who entered into cohabiting unions also differed from those who remained in dating relationships. Those who cohabited were younger when they began their sexual relationship, and were more likely to be white and college educated. Dating women were significantly more likely than cohabiting and married women to have begun their relationship recently, to be parents, and to have previously lived with a cohabiting partner. They also reported the highest mean number of lifetime sexual partners.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women Age 18–44, by Union Status

| Column A |

Column B |

Column C |

Column D |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Women | Married, no cohabitation | Cohabitors (All) | Single, currently dating | |

| Background characteristics | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean |

| Lived with both parents (reference) | ||||

| Lived with both parents (reference) | 61.0% | 75.7% b | 60.2% | 57.9% a |

| Lived with single parent | 16.6% | 10.3% b | 15.5% | 19.8% a,b |

| Lived with step- & biological parent | 17.2% | 10.1% b | 19.0% | 16.7% a,b |

| Lived with no biological parents | 5.2% | 3.8% b | 5.3% | 5.5% |

| Parents not married at time of birth | 23.8% | 9.4% b | 22.8% | 29.3% a,b |

| Mother's education Less than high school | 18.9% | 20.4% | 19.4% | 17.7% |

| High school degree (reference) | 31.2% | 27.1% b | 32.1% | 31.3% a |

| Some college | 28.5% | 23.8% b | 29.2% | 28.9% a |

| College degree | 21.4% | 28.7% b | 19.3% | 22.2% a,b |

| Age at interview | 27.09 | 28.84 b | 27.34 | 26.22 a |

| Age at first sex with most recent partner | ||||

| Mean | 23.73 | 23.63 b | 23.07 | 24.68 a |

| <18 | 8.2% | 7.4% b | 10.2% | 5.7% b |

| 18–20 | 25.6% | 23.5% | 25.6% | 26.4% |

| 21–24 (reference) | 30.0% | 35.1% | 31.1% | 27.0% a,b |

| 25–29 | 20.8% | 19.6% | 22.4% | 18.9% b |

| 30+ | 15.4% | 14.4% b | 10.7% | 22.1% a,b |

| Race | ||||

| White (reference) | 58.8% | 62.7% | 64.7% | 49.3% a,b |

| Black | 18.2% | 11.0% | 12.6% | 28.3% a,b |

| Hispanic | 17.3% | 16.9% | 17.8% | 16.6% |

| Other | 5.7% | 9.5% b | 4.9% | 5.8% a |

| Respondent’s education (at interview) Less than high school | 12.9% | 7.0% b | 13.5% | 13.9% a |

| High school degree | 26.1% | 16.6% b | 25.9% | 29.1% a,b |

| Some college (reference) | 32.6% | 27.1% | 30.8% | 36.9% a,b |

| College degree | 28.3% | 49.3% b | 29.8% | 20.1% a,b |

| Finished HS by first sex with most recent part | 71.2% | 80.0% b | 68.8% | 72.0% a,b |

| Relationship characteristics | ||||

| Cohort of relationship start year | ||||

| 1996–2000 | 8.1% | 15.2% | 11.4% | 1.6% a,b |

| 2001–2003 | 14.9% | 27.0% b | 18.9% | 5.7% a,b |

| 2004–2006 | 25.8% | 26.8% | 29.2% | 20.7% a,b |

| 2007–2009 | 26.9% | 19.4% | 23.3% | 34.2% a,b |

| 2010–2012 | 24.3% | 11.6% b | 17.3% | 37.8% a,b |

| Number of other sexual partners | 5.39 | 2.42 b | 5.41 | 6.24 a,b |

| Respondent previously cohabited | 33.4% | 13.0% b | 32.5% | 40.6% a,b |

| Respondent had child prior to union | 18.5% | 7.6% | 17.1% | 23.7% a,b |

| Respondent is ever pregnant during union | 18.8% | 17.9% | 17.9% | 20.3% |

| Time to marriage or cohabitation, in months | 17.32 | 18.90 b | 12.85 | n/a |

| Share of sample | 100.0% | 9.0% | 46.5% | 44.5% |

| Observations | 6,086 | 545 | 2,831 | 2,710 |

Source: 2006–10 and 2011–13 NSFG Female respondent file. Women between the ages of 18–44. Restricted to relationships that started between 1–10 years prior to the interview date.

Note: indicates significant difference from direct marriers

indicates significant difference from cohabitors at the p<.05 level.

Among our initial sample of women whose most recent relationship began within 10 years of the interview date, a relatively small proportion – only 9.0% – married directly. The remaining sample was roughly evenly divided between women who cohabited with their most recent partner (46.5%) and women who had not (yet) coresided with their most recent partner (44.5%). The mean duration from sexual involvement to direct marriage was about 19 months, shorter than reported by Halpern-Meekin and Tach (2013), though transitions into cohabitation occurred at a similar tempo (approximately 13 months).

RESULTS

Life Table Estimates

Our life table estimates of relationship trajectories reveal that transitions into cohabitation are most common early on in sexual relationships (Table 2, Panel A). Nearly one quarter of women had begun cohabiting within six months of becoming sexually involved, whereas only 3.4% had married directly. By the 12-month mark, the proportion of women entering into cohabiting unions was more than five times greater than the proportion marrying directly (33% vs. 6%). Transitions into cohabitation continue to outpace transitions into marriage in subsequent months; nearly half of women’s most recent sexual relationships (47.3%) became cohabiting unions by 24 months, still four times greater than the share marrying directly (10.8%). Overall, of most recent sexual relationships that persisted at least three years, less than a third remained in a sexual relationship without transitioning into either cohabitation or directly to marriage.

Panel B of Table 2 provides information about the experiences of women whose most recent sexual relationship transitioned into cohabiting unions. Transitions from cohabitation to marriage occurred far more gradually than did transitions into cohabiting unions. Only 16.2% of never married women who entered into a cohabiting union in their most recent sexual relationship had married within 12 months of moving in with their partner. In fact, by the third year mark the proportion of women who had married their cohabiting partner had still not approached the proportion that remained cohabiting or had broken up (44.2% vs. 55.5%, respectively).

Multivariate Results

Union transitions in sexual relationships.

The risk ratios of cohabitation and marriage relative to continuing in a dating relationship are presented in Table 3, in three sequential models. The first (Model A) examines the tempo of relationship transitions as a function of the intervals since the start of the sexual relationship. Next, we include controls for social class indicators (Model B). Last, we include controls for respondents’ race and relationship history (Model C). Relative risk ratios (or the exponentiated coefficients of the parameter estimates) can be interpreted as the change in the risk ratio of entering a cohabiting or marital union associated with a unit increase in the independent variable. These analyses serve to identify key temporal and social class differences in union formation processes.

Results from Table 3 (Model A) reveal the temporal patterns of transitioning into cohabitation or direct marriage, confirming the life table results. Most cohabiting unions were formed quickly – within the first year of sexual involvement. Those who did not enter into shared living early on tended not to cohabit. The relative risk of cohabiting for women who have been sexually involved for six or fewer months was 49.1 percent greater than for women who had been dating for 13 to 18 months. In fact, the odds of cohabiting decreased substantially with increased duration in a relationship; the relative risk of cohabiting was 38.4 percent greater among those sexually involved for six or fewer months than it was for women who dated for seven to 12 months (RRR = 1.491/1.077), while those involved for longer than three years were significantly less likely to cohabit than those involved for over a year but less than 18 months. In fact, at the shortest duration (less than six months) women were significantly more likely to cohabit than to marry. The pace of entrance into marriage is less consistent, and none of the timing coefficients in Model A reached statistical significance, suggesting no evident trend in timing to marriage from sexual involvement.

The tempo patterns regarding entrance into cohabitation and marriage are largely unchanged upon controlling for family social class (Model B). As hypothesized, women who experienced family disruption or reformation – living with a single mother or in a step-family by adolescence – are substantially less likely to marry than to enter into a cohabiting union or remain in a non-residential sexual relationship. But women who experienced parental union instability are no more likely to enter cohabiting unions than to remain in non-residential dating relationships. Women whose mothers were unmarried at birth were significantly less likely to cohabit or marry, versus staying sexually involved, than women born to married mothers. In contrast, women who grew up in more privileged families, such as those with college educated mothers, were significantly less likely to cohabit than to remain in a non-residential sexual relationship, and more likely to marry directly than to cohabit. Those who completed high school before starting their relationship, as well as those with the least educated mothers, were also significantly more like to marry directly than to remain dating or cohabit.

The temporal associations observed in the reduced model remain after accounting for racial background and women’s sexual and relationship history (Model C), with one notable exception. At longer durations, relationships are more likely to transition into marriage than cohabitation or remaining in a sexual, non-residential union; the relative risks of marrying directly are 54.8% greater among women who have been dating for three or more years relative to those involved for a year to eighteen months. Other measures operate as hypothesized once race and sexual history measures are controlled, though fewer indicators reach conventional levels of significance. The impact of maternal marital status and maternal education operate as hypothesized. Women born to unmarried mothers are significantly less likely to marry directly, relative to both cohabiting and remaining dating. And those born to college educated mothers are significantly less likely to enter cohabiting unions than to remain dating or marry directly.

Our other controls reveal how relationship tempos are shaped by background characteristics. Black women are significantly less likely than white women to both marry directly and cohabit, relative to remaining in a dating relationship. Age at the start of the sexual relationship is strongly associated with both entrance into direct marriage and entrance into cohabitation, though the pattern differs. The odds of direct marriage increase with women’s age at the start of the sexual relationship, but the pattern is curvilinear for transitions into cohabitation, with the youngest and oldest women significantly less likely to enter a cohabiting union than women in their 20s, relative to remaining in a dating relationship. Furthermore, the oldest women were significantly more likely to marry directly than to cohabit. We find no clear association between the year the sexual relationship began and transitions into either cohabitation or direct marriage, although women whose relationship began during the Great Recession (2007–2009) were significantly less likely to cohabit compared to relationships that began in the late 1990s. Our indicators of sexual history operate as expected, with greater relationship experience – more prior sexual partners, having previously cohabited, and being a mother prior to the start of the relationship – strongly associated with a lower risk of entering directly into marriage. Consistent with the demographic literature, conception is associated with both transitions into cohabiting unions as well as direct marriage, relative to dating.

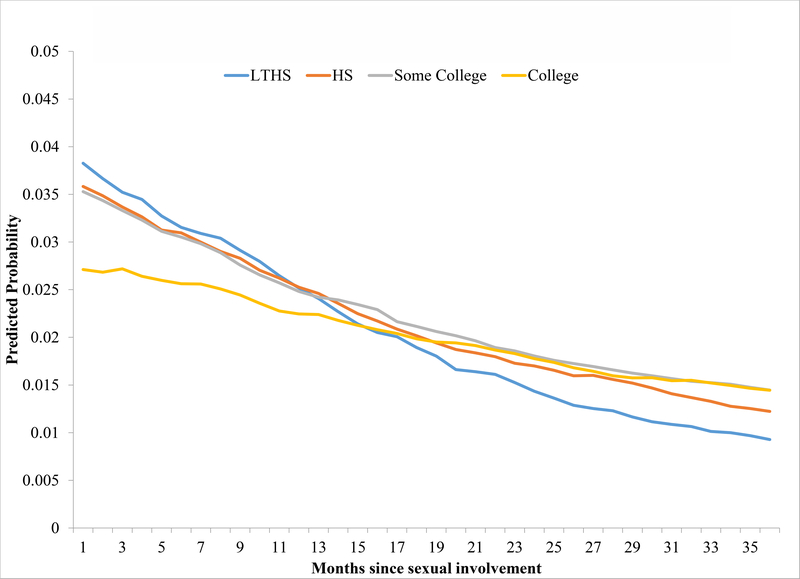

One of our goals was to examine whether tempo differences into cohabitation by social class were evident. Based on Model C of Table 3, we modeled the timing to cohabitation, relative to remaining sexually involved, separately by maternal educational attainment. This allows for the impact of duration to differ across categories. Our approach is similar to a single regression with interactions between our social class indicators and duration since first sex. Rather than six-month intervals utilized in Table 3, we instead examine a quadratic monthly measure of duration (shown in Figure 1) for ease of presentation. We then graphed conditional predicted probabilities of entering cohabitation or marriage by months since the initiation of the sexual relationship.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of cohabiting by months since first sex with most recent partner, by mother’s educational attainment

Not only are women who grow up with college educated mothers less likely to cohabit, but those who do cohabit enter into shared living at significantly slower tempos than do women who grew up with mothers who lacked a college degree, as shown in Figure 1. Entry into cohabitation occurs most slowly among women whose mothers had a college degree. After over a year of sexual involvement the cohabitation trajectories of women with the most educated and less educated mothers begin converging; not until about 19 months after the start of their sexual relationship do women with highly educated mothers catch up with those with moderately educated mothers. Figure 1 also demonstrates that transitions into cohabitation have the highest probability of occurring early on in sexual relationships. The longer a woman has not entered a coresidential union with her sexual partner, the lower her odds of subsequently doing so.

Transitions from Cohabitation: Does Tempo to Cohabitation Matter?

We turn now to our second multivariate analysis. Because previous studies have extensively explored the factors associated with marital transitions of cohabitors, we focus mainly on our temporal measures. Previously, we showed how rapidly many women entered cohabiting unions. Results from Table 4 (Model A) reveal that cohabitors who moved in with their partners within the first year were, in fact, less likely to transition into marriage than those who took longer, though net of other controls this effect is negative but only marginally significant (p < .053 ). Once women are living with a partner they are more likely to marry with each month since moving in, but at a declining rate. The odds ratio for our linear measure of months since the start of the cohabitation is greater than one, while the quadratic term is almost one (with rounding), and both terms are significant.

Table 4.

Odds ratios from logistic regression models predicting likelihood of marrying from start of cohabiting union: women aged 18–44 whose relationship began within 10 years of the interview

| Model A | Model B | Model C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moved in together within one year | 0.835 † | 0.938 | 0.848 † |

| Duration since move-in (months) | 1.015 * | 1.019 ** | 1.019 ** |

| Duration since move-in squared (months) | 1.000 ** | 1.000 ** | 1.000 ** |

| Family structure at age 14 (Ref=Lived with both parents) | |||

| Lived with single parent | 0.766 * | 0.824 | |

| Lived with step parent | 0.830 | 0.813 † | |

| Lived with no biological parent | 1.237 | 1.481 † | |

| BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| Education at move-in date (Ref=Some College) | |||

| Less than high school | 0.603 *** | 0.581 *** | |

| High school | 0.870 | 0.820 † | |

| College | 1.948 *** | 1.790 *** | |

| Race (Ref=White) | |||

| Black | 0.605 *** | ||

| Hispanic | 0.631 ** | ||

| Other | 0.606 * | ||

| Year began cohabiting | 0.965 ** | ||

| RELATIONSHIP HISTORY | |||

| Number of sexual partners | 0.999 | ||

| Respondent had prior cohabiting unions | 1.030 | ||

| Respondent had a child prior to current union | 1.005 | ||

| Respondent was pregnant (time-varying) | 1.720 *** | ||

| df | 3 | 9 | 17 |

| Number of Observations | 74,383 | 78,319 | 74,383 |

Source: 2006–13 NSFG Female respondent file. Women ages of 18–44 whose most recent sexual relationship was coresidential.

Note: The reference category includes those who remain in cohabiting relationships or had broken up by the time of interview. Only 278 of the 2,554 women who entered cohabiting unions had broken up with their partners by the time of the interview, too few to analyze separately. Duration is measured as months since move-in. Underlined terms indicate significant differences between breaking up and marrying at the p<.05 level.

p ≤.001

p ≤01

p ≤.05

p≤.10.

Note: Model run with an indicator for negative duration recode produced no significant difference between those reporting positive durations and those reporting negative durations between first sex and move-in, which were then recoded based on NSFG instructions.

Accounting for social class of family of origin and own educational attainment (Model B) weakens the association between duration to cohabitation and marriage to insignificance, though the temporal effects of timing since entrance into cohabiting unions remain the same. Even after accounting for the tempo into shared living and duration since the start of the cohabitation, cohabiting women’s educational attainment is strongly associated with transitions into marriage. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Kuo and Raley 2016; Lichter et al. 2006).

Accounting for race and relationship history (Model C) increases the significance of our tempo measures, though the effects of family structure and respondents’ education are weaker. That may be due to the associations between family structure, race, and the onset and progression of sexual relationships (Cavanagh 2007, 2011). Women who moved in within the first year of their sexual relationship demonstrated odds of marrying their partner that were marginally significantly lower than for women who deferred cohabiting for over a year. The temporal pattern of transitioning from cohabitation into marriage remained the same; the probability of marrying increased with each month since moving in, but at a slower rate.

Educational attainment remains a strong predictor of transitions from cohabitation into marriage after controlling for other factors such as race and relationship history. Less educated women are significantly less likely to marry their cohabiting partner than are women who have completed college. Women college graduates have relative risks of marrying that are 79% greater than women who have some post-secondary schooling but no degree, relative to remaining in their cohabiting union. Unlike earlier studies of cohabiting women’s transitions into marriage (e.g., Brown 2000; Sassler and McNally 2003), where women’s educational attainment was not a strong predictor of union transitions, our results reveal further widening in disparities between college educated women and others. We also interacted our tempo measures by educational attainment (results not shown), to determine whether timing to cohabitation or since the start of living together differentially influenced union transitions. The negative association between moving in with a partner within the first year of the start of the relationship and marriage was only significant for women who had graduated from college.

Racial minorities exhibit significantly lower odds of transitioning from cohabitation to marriage than do their White counterparts; there are no significant differences between Black and Hispanic cohabitors in their odds of marrying. We also find an interesting temporal effect, as cohabiting unions that began in more recent years were significantly less likely to transition into marriage than those that began in the late 1990s. Furthermore, cohabitors who conceived after moving in with their partner exhibited an enhanced likelihood of marrying.

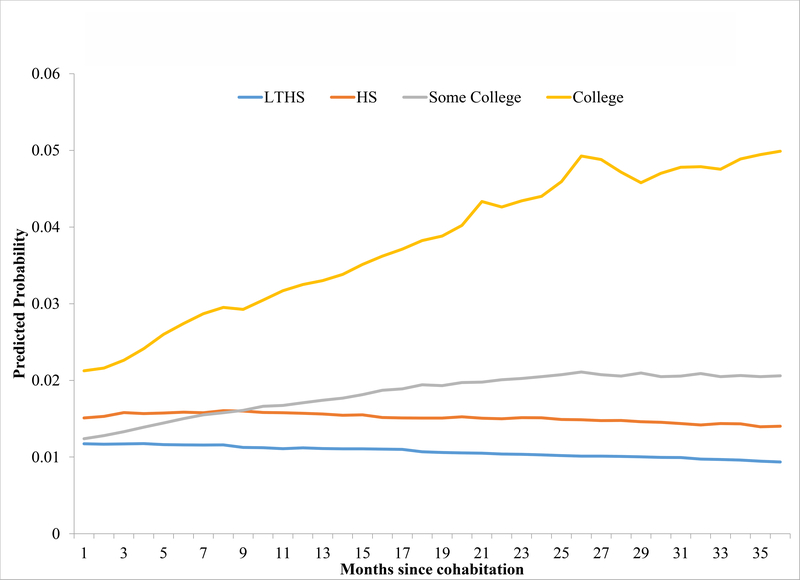

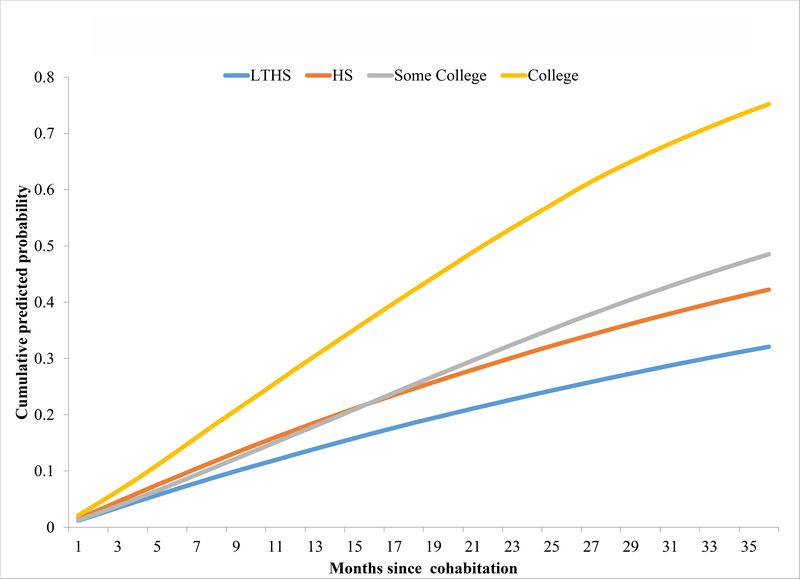

To further illustrate tempo variations in relationship transitions, we model the logistic regressions shown in Table 4 by the respondents’ educational attainment, allowing the impact of duration to differ across categories of education. Figure 2 presents monthly predicted probabilities of marrying separately for each of the education groups, while Figure 3 demonstrates cumulative predicted probabilities. Results from Figure 2 confirm the patterns of Table 4; the probabilities of marrying are higher, at every duration, for the college educated, followed by those with some post-secondary schooling. Among high school graduates, the odds of marrying decrease slightly with each additional month they cohabit with their partner, and a similar pattern is shown among high school dropouts. These monthly patterns cumulate to very different outcomes, as seen in Figure 3. College educated women are much more likely to transition from cohabitation to marriage than their lower-educated counterparts. After three years, college-educated cohabiting women are nearly twice as likely to have married as women with only a high school degree. This further confirms how cohabitation serves a different purpose for highly-educated women compared to their less advantaged counterparts. College-educated women are much more likely to use cohabitation as a stepping stone to marriage.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of marrying, by respndent’s education at cohabitation

Figure 3.

Cumulative predicted probability of marrying by months since move in, by respondent’s educational attainment

CONCLUSION

Previous theory and research on the progression of sexual relationships into cohabitation or marriage, and from cohabitation into marriage are limited. Most research on cohabitation begins observing respondents or couples only at the time of coresidence, and overlooks the period preceding the entrance into shared living. But the tempo of transitions into cohabitation may reflect various factors that influence subsequent trajectories. In this article, we used retrospective data from the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 NSFG to examine the progression of women’s most recent sexual relationships into direct marriage or cohabitation, and then assessed whether rapid or more tempered transitions into cohabitation were associated with subsequent transitions into marriage. The role of social class in differentiating the tempo of progression, into direct marriage or cohabitation, and from cohabitation to marriage, was a particular focus of our study.

The empirical results expose several patterns of interest to family demographers. First, they reveal that transitions into cohabiting unions occur rapidly, on average, once couples become sexually involved. The likelihood of entering cohabiting unions declines the longer women remain sexually involved. The rapid tempo to shared living exhibited among women from less advantaged backgrounds is consistent with both qualitative (Sassler 2004; Sassler and Miller 2011) and quantitative research (Sassler, Michelmore, and Holland 2016), and suggests that economic reasons may play a larger role as an impetus into shared living than compatibility testing. Women who enter rapidly into cohabiting unions may view living together as a more intensive form of dating, or an alternative to being single, as well as a means to take advantage of factors (e.g., economies of scale, companionship) formerly touted as benefits of marriage.

Second, our analysis reveals important social class distinctions in the tempo of transitions into cohabitation, and from cohabitation into marriage. These findings shed some light on the processes contributing to diverging relationship trajectories. Rapidly formed cohabiting unions are less likely to transition into marriage than are cohabitations that are formed more slowly. But it is women from less advantaged family backgrounds who are more likely to transition quickly from sexual involvement to cohabitation. For the most educated women, in contrast, a protracted period of sexual involvement prior to cohabitation suggests that cohabitation is more often utilized as a precursor to marriage. Even as some social commentators urge couples to “slow down” in forming intimate relationships (Cherlin 2009), better understanding the factors associated with expedited or delayed transitions into cohabitation is required. The relationship between rapid entrance into cohabitation and subsequently lower levels of dedication or commitment proposed by Stanley and colleagues (2006) may be spurious. Negative selection of cohabitors with poorer economic traits accounts for lower levels of marital quality (Spencer and Beattie 2012) as well as higher levels of divorce (Lu, Qian, Cunningham, and Li 2012). Nonetheless, such studies fail to account for timing into shared living, which previous research has found to matter with regards to relationship quality and satisfaction (Sassler et. al. 2012). Additional exploration is required to ascertain to what extent decisions to cohabit are motivated by economic difficulties, housing exigencies, or other factors such as unintended pregnancy, as some qualitative work has suggested (Sassler 2004; Sassler and Miller 2011). Doing so will require data better suited for studying transitions in the labor force or housing market.

Third, we find no evidence that those who rapidly moved in with their current partners progressed at an equally accelerated pace into marriage. Instead, our findings suggest that rapid transitions into cohabitation may reduce the odds of transitioning into marriage, though these results are only weakly significant. We cannot, of course, directly address the marital intentions of women entering into cohabitations, but various studies have highlighted an important finding that ours further extends (cf. Lichter et al. 2006): among cohabiting women, the less advantaged are far less likely to transition into marriage than their counterparts with more education and advantaged family backgrounds.

There are, of course, limitations in our approach. We were not able to ascertain how long couples were romantically involved prior to engaging in sexual activity, which may be another key predictor of relationship quality. Existing research suggests that the tempo of progression from romantic unions into sexual ones has remained relatively consistent, though the data sources used for these inferences are imperfect; such work suggests that one-third to forty percent of American adults become sexually involved within the first month of romance (Busby et al. 2010; Cohen and Shotland 1996; Regnerus and Uecker 2011). Nonetheless, the earliest piece of the puzzle – when relationships started and how they progress to sexual involvement – is still missing. Furthermore, we are unable to determine if the tempo to shared living is associated with poorer (or higher) quality relationships, as measures of relationship quality are not obtained in the NSFG. Also lacking in the NSFG is information about employment or schooling transitions that may shape union transitions in important ways.

Other studies of transitions from cohabitation into marriage have limited their time frame to shorter periods, such as cohabiting unions formed in the previous five years, as a means of reducing recall bias. Our longer period of coverage, ten years, over-represents the outcomes of relationships that persisted for longer periods of time, or more “successful” unions. We miss many short term sexual relationships (Sassler et al. 2016), as well as less stable relationships formed within 10 years of the interview date that dissolved more than 12 months prior to the interview date, due to data limitations. Even though we find no evidence of calendar year trends in transitions into cohabitation, our results suggest that more recently-formed cohabitations are less likely to transition into marriage. This is consistent with evidence from other studies that contemporary cohabitations are taking longer, on average, to transition to marriage than those formed in earlier time periods (Lichter et al. 2006; Manning et al. 2014). It also suggests that for some (particularly the less educated) cohabitation may be transforming into an alternative to marriage. Other data sources that focus on cohorts may better enable us to untangle whether our associations are a function of time, opportunity, or exposure.

Clearly, our analysis represents a first step in learning about the tempo of sexual relationship progression into cohabitation and beyond. The underlying presumption of those concerned with the quality and stability of contemporary relationships is that building strong relationships requires time. That more advantaged women progressed more slowly into shared living in their most recent relationship, and were also more likely to marry those partners, seems to further substantiate the “go slow” (or slower) argument (Cherlin 2009). But it begs the question of which factors enabled those women to transition more slowly into shared living. A better understanding of the mechanisms resulting in faster or slower relationship tempos is needed to shed additional light on the social class dynamics increasingly evident in the family building patterns of today’s youth.

Footnotes

The meaning of “dating” was left up to the respondent; no information was obtained about when the sexual relationship began. These were retrospective reports of relationships that began, on average, in the mid-1980s and early 1990s.

Men reported shorter durations between dating and spending the night, and between spending the night and officially living together, but a longer duration from cohabitation until marriage than women. Couple-level disagreement over start times of different stages was common.

In the 2006–10 NSFG, 90% of women reported having at least one sexual partner in the past 12 months, as did 85% of the women in the 2011–2013 NSFG.

The NSFG defines living together as having a sexual relationship while sharing the same usual residence. This specification results in a smaller proportion of cohabitors than found in some other nationally representative samples (e.g., Sassler & Joyner 2011).

Estimating the duration to cohabitation resulted in a number of women with negative durations between first sex and cohabitation, due to inconsistencies in reported dates (n=306). After consulting with researchers at the NSFG, we adjusted 84 cases where the difference between the date of first sex and the move-in date was one month, assuming that these two events happened at approximately the same time. We adjusted another 64 cases where the dates of first sex and move-in resulted in a negative duration, as when the respondent was asked how old they were at each of these events, a positive duration was calculated between date of first sex and date of cohabitation/marriage. Finally, we adjusted 2 cases where a negative duration resulted from imputing the season of first sex or move-in when respondents did not report a precise month. All told we adjusted 150 cases following these NSFG guidelines.

Additional analyses utilizing narrower windows (5 or 8 years, for example) revealed that the main results were quite similar, though given fewer transitions, often did not reach conventional levels of significance.

Using six-month intervals yielded the lowest BIC, when compared to a linear or quadratic function of duration, and therefore provided the best model fit of the data.

Over ninety percent had entered their cohabiting union within 40 months; the final 5% were sexually involved for over 45 months before entering into shared living, with the longest duration between sexual involvement and coresidence being 119 months.

An earlier version was given at the 2012 National Survey of Family Growth Research Conference, and at the 2013 annual meeting of the Population Association of America.

Contributor Information

Sharon Sassler, Department of Policy Analysis & Management, 297 Martha Van Rensselaer Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, Sharon.Sassler@Cornell.Edu, 607-254-6551 (Office Phone), 607-255-4071 (Fax).

Katherine Michelmore, The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, 426 Eggers Hall, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York 13244.

Zhenchao Qian, Department of Sociology, Population Studies and Training Center, Brown University, 68 Waterman Street, Providence, RI 02912.

References

- Allison PD (1984). Event History Analysis. Beverly Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR 2005. The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. The Future of Children, 15, 75–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino WS (1991). Family-structure and home-leaving: A further specification of the relationship. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 999–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Astone NM, and McLanahan SS (1991). Family structure, parental practices and high school completion. American Sociological Review, 56, 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 833–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L and Lu HH (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby DM, Carroll JS, and Willoughby BJ (2010). Compatibility or restraint? The effects of sexual timing on marriage relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 766–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan S, and England P (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41, 237–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE (2007). Puberty and the education of girls. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70, 186–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE (2011). Early pubertal timing and the union formation behaviors of young women. Social Forces, 89, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, Crissey SR, and Raley RK (2008). Family structure history and adolescent romance. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 698–714. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2009). The Marriage-Go-Round. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (1995). Parental divorce in childhood and demographic outcomes in young adulthood. Demography, 32, 299–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkberg M (1999). The price of partnering: The role of economic well-being in young adults’ first union experiences. Social Forces, 77, 945–968. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LL, and Shotland RL (1996). Timing of first sexual intercourse in a relationship: Expectations, experiences, and perceptions of others. Journal of Sex Research, 33, 291–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey EC, Mott FL, and Neubauer SA (2002). Friendships and early relationships: Links to sexual initiation among American adolescents born to young mothers. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34, 118–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch JF, and Francesconi M (2001). Family structure and children’s achievements. Journal of Population Economics, 14, 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB (2007). Trends in premarital sex in the United States, 1954–2003. Public Health Reports, 122, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF (2008). The intersections of social class and the transition to adulthood. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 119, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn ND (2002). A plea for greater concern about the quality of marital matching In Hawkins AJ, Wardle LD, & Coolidge DO (Eds.), Revitalizing the institution of marriage for the twenty-first century (pp. 46–58). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK and Goldscheider C (1998). The effects of childhood family structure on leaving and returning home. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 745–756. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR and Kenney CT (2001). Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for US women. American Sociological Review, 66, 506–519 [Google Scholar]

- Graefe DR, and Lichter DT (1999). Life course transitions of American children: Parental cohabitation, marriage, and single motherhood. Demography, 36, 205–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2014). Trends in cohabitation outcomes: Compositional changes and engagement among never married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 826–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Meekin S and Tach L (2013). Discordance in couples’ reporting of courtship stages: Implications for measurement and marital quality. Social Science Research, 42, 1143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harknett K and Kuperberg A (2011). Education, labor markets and the retreat from marriage. Social Forces, 90(1), 41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymowitz KS, Caroll JS,, Wilcox WB, and Kaye K (2013). Knot Yet: The Benefits and Costs of Delayed Marriage in America. The National Marriage Project. http://twentysomethingmarriage.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Jamison TB and Ganong L (2011). We’re not living together: Stayover relationships among college-educated emerging adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 536–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S and Bumpass L (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo Janet Chen-Lan and Kelly Raley R (2016). Diverging patterns of union transition among cohabitors by race/ethnicity and education: Trends and marital intentions in the United States. Demography, 53, 921–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A (2003). Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. University of California Press, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z, and Mellott LM (2006). Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography, 43, 223–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Turner RN, and Sassler S (2010). National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39, 754–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Bo, Qian Z, Cunningham A, and Li. CL (2012). Estimating the effect of premarital cohabitation on timing of marital disruption: Using propensity score matching in event history analysis. Sociological Methods & Research, 41, 440–466. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD (2013). Trends in cohabitation: Over twenty years of change, 1987–2010. NCFMR Family Profiles, FP-13–12. Accessed at Http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu.

- Manning WD, Brown SL, and Payne KK (2014). Two decades of stability and change in age at first union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 247–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD and Smock PJ (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD and Smock PJ (1995). Why marry? Race and the transition to marriage among cohabitors. Demography, 32, 509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Muller C, and Frisco ML (2006). Parental involvement, Family structure, and adolescent sexual decision making. Sociological Perspectives, 49, 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH, Heuveline P, and Guillot M (2001). Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes. Oxford UK: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus M and Ueker J (2011). Premarital Sex in America: How Young Americans Meet, Mate, and Think about Marrying. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR and VandenHeuvel A (1990). Cohabitation: A precursor to marriage or an alternative to being single? Population and Development Review, 16, 703–726. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg-Thomas SE and Dush CK (2014). Casual sexual relationships and mental health in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S (2010). Partnering across the life course: Sex, relationships, and mate selection. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 557–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S (2004). The process of entering into cohabiting relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler SF, Addo F and Lichter DT (2012). The tempo of sexual activity and later relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74,708–725. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S and Joyner K (2011). Social exchange and the progression of sexual relationships in emerging adulthood. Social Forces, 90, 223–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S and McNally J (2003). Cohabiting couples’ economic circumstances and union transitions: A re-examination using multiple imputation techniques. Social Science Research, 32, 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S and Miller AJ (2011). Class differences in cohabitation processes.” Family Relations, 60,163–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S and Miller AJ (2017). Cohabitation Nation: Gender, Class, and the Remaking of Relationships. University of California Press, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Michelmore K, and Holland JA (2016). The progression of sexual relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(3), 587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Sawhill IV (2014). Generation Unbound: Drifting into Sex and Parenthood without Marriage. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, and Porter M (2005). ‘Everything’s there except money’: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 680–696. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JL and Beattie BA (2012). Reassessing the link between women’s premarital cohabitation and marital quality. Social Forces, 91, 635–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades G, and Markman HJ (2006). Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations, 55, 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, and Whitton SW (2010). Commitment: Functions, formation, and the securing of romantic attachment. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2, 243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman J (2003). Childhood living arrangements and the formation of coresidential unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 507–524. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A (1991). Influence of marital history of parents on the marital and cohabitational experiences of children. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 868–894. [Google Scholar]