Abstract

Myxomas originating from the aortic valve are rare. We report a 40-year-old male patient who presented to the King Fahd Hospital of the University, Khobar, Saudi Arabia, in 2017 with a stroke. Transoesophageal echocardiography indicated a mobile mass measuring 6 × 2 mm attached to the right coronary cusp of the aortic valve and a mobile interatrial septum with a small patent foramen ovale (PFO). The patient underwent surgical excision of the mass and direct closure of the PFO. Histopathology confirmed the mass to be a myxoma. Despite their rarity, the recognition and treatment of valvular myxomas is very important; moreover, clinicians should be aware that affected patients may present with an embolic stroke.

Keywords: Aortic Valve, Myxoma, Patent Foramen Ovale, Stroke, Transesophageal Echocardiography, Case Report, Saudi Arabia

Myxomas originating from the cardiac valves are uncommon.1,2 These benign tumours typically occur between the fourth and seventh decades of life and usually affect women more commonly than men.1 The condition is mostly sporadic in nature, but can also be familial.2 Myxomas are true neoplasms in that they are derived from primitive multipotent mesenchymal cells which may exist as embryonic remnants in the heart wall.3

Rarely, myxomas may arise from both the ventricular aspect and the margin of the aortic valve cusps; moreover, one or both leaflets may also be affected.4 Although transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) aids in the assessment of such masses, histopathology is considered the gold-standard method to confirm a diagnosis.4,5 This report describes an atypical case of aortic valve myxoma and patent foramen ovale (PFO) presenting with a cerebral stroke. Such cases serve to increase awareness of the varying presentation of aortic valve myxomas and highlight appropriate investigations and management of this condition.

Case Report

A 40-year-old male patient presented to the King Fahd Hospital of the University (KFHU), Khobar, Saudi Arabia, in 2017 with sudden-onset dysphasia, left ataxia, nausea and vomiting over the preceding two hours. The patient reported having had a previous stroke at the age of 11 years; however, he was unable to provide any information about the event. At presentation, the patient was alert, oriented and had stable vital signs. All laboratory investigation findings were within normal limits and electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm. As a result, the case was transferred to the stroke team. Urgent computed tomography (CT) of the head showed evidence of the prior ischaemic stroke event in the right occipital lobe and right cerebellum. An intravenous thrombolytic was administered in accordance with hospital guidelines. Subsequently, the patient was admitted to the inpatient department and received 150 mg of aspirin and 75 mg of clopidogrel. Symptoms improved over the course of the following three days. However, further investigations were undertaken to determine the source of the stroke.

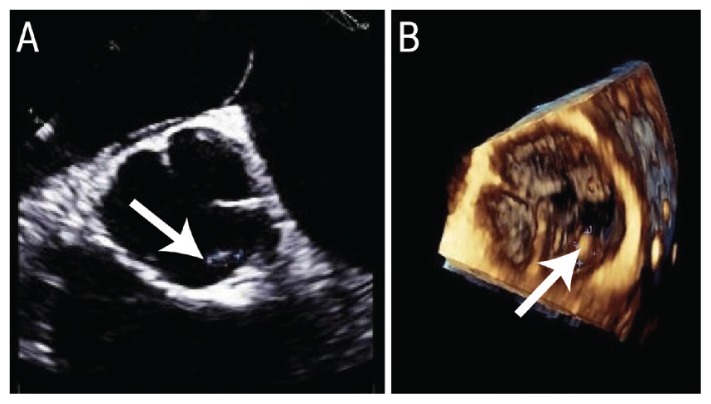

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that the patient had suffered an acute ischaemic stroke, with a multifocal area of diffusion restriction within the right cerebral and superior cerebellar peduncles and both cerebellar hemispheres, as well as hyperintensities on T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI sequences. However, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) did not show any clear source of emboli. Accordingly, TEE was performed and revealed a small mobile mass measuring 6 × 2 mm attached to the right coronary cusp (RCC) of the aortic valve and a mobile interatrial septum with a small PFO visible with agitated saline contrast [Figure 1]. No significant arrhythmia was noted on a Holter monitor. A papillary fibroelastoma (PFE) was suspected.

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiography of a 40-year-old male stroke patient in (A) bi-plane short-axis view showing a small mass in the right coronary cusp of the aortic valve measuring 3 × 5 mm and (B) three-dimensional enfaced view showing the mass measuring 6 × 2 mm.

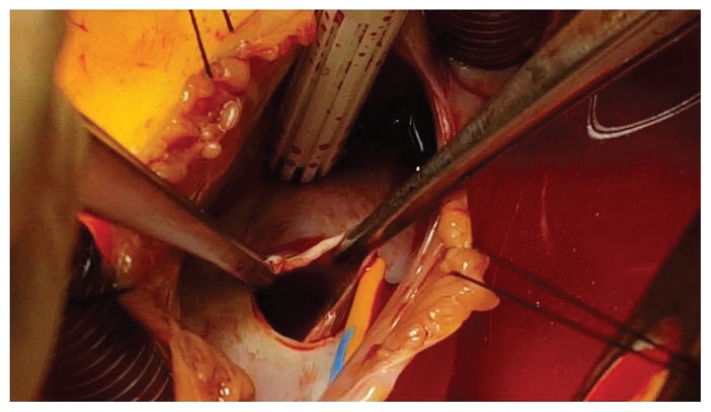

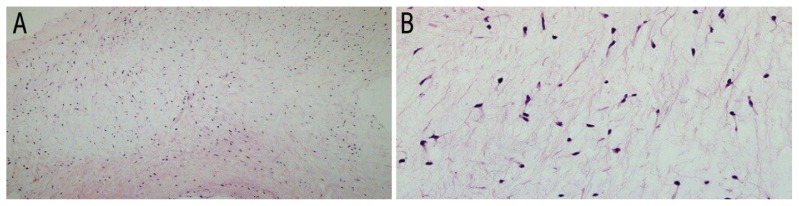

After two weeks of stroke management, the decision was made excise the mass along with closure of the PFO to prevent any future embolic events. The surgical procedure was performed while the patient underwent cardiopulmonary bypass. During the surgery, the PFO was visible as an opening between the right and left atria [Figure 2]. The mass was successfully excised from the RCC and the PFO was closed. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged five days later. A histopathological examination of the excised mass showed a paucicellular lesion composed of stellate and oval cells with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, fine chromatin and indistinct cell borders [Figure 3]. These features were consistent with a diagnosis of myxoma.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photograph of the heart of a 40-year-old male stroke patient showing an opening between the right and left atria measuring 10 × 10 mm.

Figure 3.

Haematoxylin and eosin stains at (A) x40 magnification showing a hypocellular lesion in a myxoid matrix and (B) at x200 magnification showing stellate and oval cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders.

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only 11 cases of aortic valve myxoma have been previously reported in the literature [Table 1].4–14 Interestingly, nine of these previously reported patients were male, as in the current case; this is contrary to the usual female preponderance of myxoma cases.1,4–9,11,13,14 Overall, six aortic valve myxoma patients were symptomatic, with symptoms largely attributable to distal embolisation and ischaemia, including three cases with stroke, two with myocardial infarctions and one with limb ischaemia.4,6,8,11–13 Clinicians should therefore be aware of stroke as a potential presentation of aortic valve myxoma.

Table 1.

| Author and year of case* | Age/gender | Presentation | History | Imaging | Site | Size in cm | Complication | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kennedy et al.8 (1995) | 23/M | Leg pain | None | TTE | RCC and LCC | 1.5 | Limb ischaemia | AVR |

| Watarida et al.9 (1997) | 58/M | Asymptomatic | None | TTE | RCC | 1.1 × 1 | None | AVR |

| Ramsheyi et al.6 (1998) | 34/M | Facial haemiparesis | None | TTE and TEE | RCC | 1 | Stroke | AVR |

| Okamoto et al.10 (2006) | 61/F | Endocarditis | HTN and DM | TTE | LCC | 1 × 1 | None | Resection |

| Dyk et al.11 (2009) | 15/M | Chest pain | None | TTE and TEE | NCC | 4 × 1 | MI | Resection |

| Koyalakonda et al.12 (2011) | 60/F | Paroxysmal AF | AF and HTN | TTE and TEE | RCC | 1 × 1 | Stroke | Resection |

| Fernández et al.13 (2012) | 28/M | Haemiparesis | Epilepsy | TTE | RCC and LCC | 1.5 × 0.7 | Stroke | AVR |

| Kim et al.7 (2012) | 72/M | Shortness of breath | HTN | TTE | NCC | 1.5 × 0.8 | None | AVR |

| Javed et al.4 (2014) | 81/M | Leg pain | HTN, CKD and PAD | CT, angiography and TEE | LCC | 1.8 × 1.2 | Acute MI | CABG and resection |

| Prifti et al.5 (2015) | 13/M | Dyspnoea and angina | None | TTE and TEE | RCC and LCC | 0.6 × 0.2 | None | AVR |

| Ji et al.14 (2017) | 17/M | Heart murmur | None | TTE | NCC | 2 | None | AVR |

| Present case (2018) | 40/M | Dysphasia, ataxia and nausea | Previous stroke | TTE and TEE | RCC | 0.6 × 0.2 | Stroke and PFO | Excision and PFO closure |

TTE = transthoracic echocardiography; RCC = right coronary cusp; LCC = left coronary cusp; AVR = aortic valve replacement; TEE = transoesophageal echocardiography; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; NCC = non-coronary cusp; MI = myocardial infarction; AF = atrial fibrillation; CKD = chronic kidney disease; PAD = peripheral arterial disease; CT = computed tomography; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PFO = patent foramen ovale.

In all cases, the diagnosis was confirmed via histopathological examination.

The pathogenesis of ischaemic events in aortic valve myxoma could be due to either embolic debris derived from the tumour itself or from a thrombus around the tumour.12 In the current case, the patient was also diagnosed with PFO, a potential cause of embolic stroke in which a paradoxical embolism may pass through a PFO via right-to-left shunting (RLS).15 However, in the current case, the observed PFO was very small in size and therefore would not be able to cause the RLS of an embolus.

The differential diagnosis of an aortic valve myxoma includes vegetation, a thrombus, PFE and Lambl’s excrescences; these conditions can be distinguished by their microscopic and immunohistochemical characteristics.7,10,13 In addition, thrombi and myxomas can be differentiated using two-dimensional echocardiography; the former typically present with a layered appearance, while an area of echolucency may be observed within the tumour in the latter.7 Moreover, vegetations of the heart valves are a sign of infective endocarditis; however, this was ruled out in the current case due to a lack of history of this condition.10,16

On imaging, the size, shape, attachment site, mobility and location of a cardiac mass can aid in the exact diagnosis, along with the patient’s clinical presentation.17–19 For example, in PFE cases, the tumour appears as a small mass attached to the mitral or aortic valve, usually located downstream and attached by a small pedicle; such masses are more common and often mobile and appear irregularly-shaped with delicate frond-like surfaces.7,17,18 In contrast, Lambl’s excrescences appear as filiform fronds located near valve closure lines.20 Radiologically, TEE is superior to TTE in identifying a cardiac mass and defining its exact location, attachment to the underlying tissue and relation to surrounding structures.21,22 Among previously reported cases of aortic valve myxoma, 10 were identified by TTE, of which four were further confirmed via TEE.5–14 In one case, an aortic valve abnormality was first revealed via CT.4 In the current case, TEE revealed the mass to be located on the RCC of the aortic valve, thus precluding a thrombus or cardiac vegetation; however, the preoperative diagnosis was of a PFE. As with previous cases, the correct diagnosis was eventually confirmed by histopathological examination revealing a myxoid matrix with ovoid myxoma cells.4–14

Typically, the management of aortic valve myxoma cases involves the surgical excision of the tumour as well as the surrounding tissue to minimise the risk of local recurrence, as in the present case.4,10–12 During the procedure, the native aortic valve should be conserved as much as possible; however, if the tumour is too large and/or degeneration of the valvular structure occurs, aortic valve replacement (AVR) may be necessary. Among previously reported cases, seven underwent AVR, while resection alone was sufficient in three cases and one required resection and a coronary artery bypass graft.4–14 Nevertheless, regardless of treatment option, aortic valve myxoma cases require careful follow-up due to the high probability of local recurrence and distal tumour growth at the site of embolisation.5

Conclusion

An aortic valve myxoma is uncommon and may present with serious complications, such as stroke. In patients with embolic phenomena, TEE should be performed, with special attention to the valvular morphology. For valvular myxomas, aggressive surgical excision is necessary to prevent structural valve degeneration and local recurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude for the insightful comments of Dr Sari Alsuhaibani, Department of Radiology, KFHU, Dr Mohammed J. Alyousef, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, KFHU, and Mr Ahmed M. Alsahlawi, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and the great vessels. In: Rosai J, editor. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 3rd series. Washington DC, USA: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1996. p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaideeswar P, Butany JW. Benign cardiac tumors of the pluripotent mesenchyme. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2008;25:20–8. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlandi A, Ciucci A, Ferlosio A, Genta R, Spagnoli LG, Gabbiani G. Cardiac myxoma cells exhibit embryonic endocardial stem cell features. J Pathol. 2006;209:231–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Javed A, Zalawadiya S, Kovach J, Afonso L. Aortic valve myxoma at the extreme age: A review of literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202689. bcr2013202689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prifti E, Ademaj F, Kajo E, Baboci A. A giant myxoma originating from the aortic valve causing severe left ventricular tract obstruction: A case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:151. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0575-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsheyi A, Deleuze P, D’Attelis N, Bical O, Lefort JF. Aortic valve myxoma. J Card Surg. 1998;13:491–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1998.tb01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HY, Kwon SU, Jang WI, Kim HS, Kim JS, Lee HS, et al. A rare case of aortic valve myxoma: Easy to confuse with papillary fibroelastoma. Korean Circ J. 2012;42:281–3. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.4.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy P, Parry AJ, Parums D, Pillai R. Myxoma of the aortic valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1221–3. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)00969-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watarida S, Katsuyama K, Yasuda R, Magara T, Onoe M, Nojima T, et al. Myxoma of the aortic valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:234–6. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(96)00771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto T, Doi H, Kazui T, Suzuki M, Koshima R, Yamashita T, et al. Aortic valve myxoma mimicking vegetation: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36:927–9. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyk W, Konka M. Images in cardiothoracic surgery: Unusual complication of aortic valve grape-like myxoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1022. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koyalakonda SP, Mediratta NK, Ball J, Royle M. A rare case of aortic valve myxoma: An unusual cause of embolic stroke. Cardiology. 2011;118:101–3. doi: 10.1159/000327081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández AL, Vega M, El-Diasty MM, Suárez JM. Myxoma of the aortic valve. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:560–2. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji Z, Wang L, Sun J, Ye W, Yu Y, Huang H, et al. Aortic valve myxoma in a young man: A case report and review of literature. Heart Surg Forum. 2017;20:E066–8. doi: 10.1532/hsf.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homma S, Sacco RL. Patent foramen ovale and stroke. Circulation. 2005;112:1063–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez G, Valchanov K. Infective endocarditis. BJA Educ. 2012;12:134–9. doi: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mks005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shelh M. Multiplane transoesophageal echocardiography detection of papillary fibroelastomas of the aortic valve causing a stroke. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:702–3. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Hosoda Y, Kikuchi N, Kawai S. Papillary fibroelastoma of the tricuspid valve in association with an atrial septal defect: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1996;26:831–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00311648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rana BS, Monaghan MJ, Ring L, Shapiro LS, Nihoyannopoulos P. The pivotal role of echocardiography in cardiac sources of embolism. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12:i25–31. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aziz F, Baciewicz FA., Jr Lambl’s excrescences: Review and recommendations. Tex Heart Inst J. 2007;34:366–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leibowitz G, Keller NM, Daniel WG, Freedberg RS, Tunick PA, Stottmeister C, et al. Transesophageal versus transthoracic echocardiography in the evaluation of right atrial tumors. Am Heart J. 1995;130:1224–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mankad R, Herrmann J. Cardiac tumors: Echo assessment. Echo Res Pract. 2016;3:R65–77. doi: 10.1530/ERP-16-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]