Abstract

Honokiol, a natural biphenolic compound, exerts anticancer effects through a variety of mechanisms on multiple types of cancer with relatively low toxicity. Adenosine 5′-phosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an essential regulator of cellular homeostasis, may control cancer progression. The present study aimed to investigate whether the anticancer activities of honokiol in ovarian cancer cells were mediated through the activation of AMPK. Honokiol decreased cell viability of 2 ovarian cancer cell lines, with an half-maximal inhibitory concentration value of 48.71±11.31 µM for SKOV3 cells and 46.42±5.37 µM for Caov-3 cells. Honokiol induced apoptosis via activation of caspase-3, caspase-7 and caspase-9, and cleavage of poly-(adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase. Apoptosis induced by honokiol was weakened by compound C, an AMPK inhibitor, suggesting that honokiol-induced apoptosis was dependent on the AMPK/mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway. Additionally, honokiol inhibited the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. The combined treatment of honokiol with compound C reversed the activities of honokiol in wound healing and Matrigel invasion assays. These results indicated that honokiol may have therapeutic potential in ovarian cancer by targeting AMPK activation.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, honokiol, adenosine 5′-phosphate-activated protein kinase, apoptosis, invasion, migration

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common diseases in woman. The 5-year survival rates for patients with advanced ovarian cancer remain at 20-30% (1). Chemotherapy has been used to treat ovarian cancer for several decades. Alkylating agents were developed as single chemotherapy drugs during the 1970s (2). Cisplatin-based regimen was established as the standard first-line chemotherapy for patients with ovarian cancer in the late 1980s (3). Although cisplatin is a widely used and a highly active chemotherapeutic agent for ovarian cancer, its use has been limited due to its cumulative toxicities, in particular its nephrotoxicity (2). In addition, instances of intrinsic and acquired resistance to cisplatin have been observed in patients with ovarian cancer (2). Therefore, novel chemotherapeutic agents are urgently required to treat ovarian cancer, and to promote the effectiveness and decrease the side effects of cisplatin treatment.

Adenosine 5′-phosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a nutrient and energy sensor in mammalian cells, regulates glucose and lipid metabolism (4). AMPK is a heterotrimeric serine/threonine protein kinase that is composed of a catalytic α-subunit and 2 regulatory subunits, the β- and γ-subunits. Under normal physiological conditions, AMPK protects cells against various metabolic stresses by maintaining homeostatic pools of the adenosine nucleotides [adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP), and AMP] (4). However, the role of AMPK signaling in cancer has not yet been fully elucidated. Epidemiological investigations have suggested that treatment with metformin, a drug that activates AMPK, was associated with decreased incidence of diseases, including breast, lung, colon, prostate and pancreatic cancer (5-8). Experimental data have confirmed that metformin exerts an inhibitory effect on the growth of breast and pancreatic cancers (9,10). Clinical data have also confirmed that metformin may improve the overall survival of patients with diabetes and cancer either alone or in combination with chemotherapy (11,12). However, conventional AMPK activators including metformin may cause the toxic side effect of lactic acidosis with dazzling, muscle pain, tiredness and stomach pain (13). Therefore, the use of nontoxic and natural AMPK activators may be preferable to treat ovarian cancer and its chemoresistance.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) serine/threo-nine kinase, a downstream effector of AMPK, exists in 2 biochemically distinct complexes, mTOR complex 1 and mTOR complex 2. mTOR, similarly to AMPK, serves critical roles not only in cell growth and cell proliferation but also in metabolism (14). AMPK phosphorylates and activates tuberous sclerosis 1 protein (TSC1)/tuberous sclerosis 2 protein (TSC2), thereby inhibiting mTOR. mTOR leads to inhibition of downstream targets p70S6 kinase (p70S6K) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1), which are involved in cell growth primarily through the regulation of translation and protein synthesis (15). AMPK controls tumor development through the modulation of mTOR activity (16). Therefore, the AMPK/mTOR pathway is a promising target for cancer therapy.

Herbal medicine has been widely used to treat illnesses for centuries. It is the most productive source of lead compounds for drug development (17). It includes various natural compounds with biological activities and therapeutic effectiveness, with minimum side effects (17). Magnolia officinalis is a species of Magnolia. Its roots and stem bark have been used for treating thrombotic stroke, gastrointestinal complaints, anxiety, nervous disturbance, allergic diseases and cancer (18). Studies have demonstrated that Magnolia extract is a safe medicine with low toxicity (18-20). Honokiol is a natural biphenolic compound derived from the bark of Magnolia trees with anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties (21). Several mechanisms involved in the anti-tumor activities of honokiol against leukemia, breast, pancreatic and prostate cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and skin, gastric, bone and brain cancer have been suggested (22), including the induction of cell cycle arrest (23), apoptosis (24), autophagy (25), and anti-proliferative (26) and anti-invasive processes (27-29).

The present study evaluated the therapeutic potential of honokiol based on its anticancer properties, including its effects on apoptosis, migration and invasion in ovarian cancer cells. Additionally, the potential molecular mechanisms involved in its anticancer effects were explored.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Honokiol, compound C and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (DMEM), McCoy's 5A medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., (Waltham, MA, USA). RPMI-1640 Medium and Trypsin/EDTA were purchased from HyClone (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA). The Cell Counting kit-8 was obtained from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., (Kumamoto, Japan). Rabbit polyclonal anti-human caspase-3 (cat. no. 9662), mouse monoclonal anti-human caspase-7 (cat. no. 9494), rabbit polyclonal anti-human caspase-9 (cat. no. 9502), rabbit poly-clonal anti-human poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP; cat. no. 9542), rabbit monoclonal anti-human phospho-AMPK (Thr172; cat. no. 2535), rabbit polyclonal anti-human AMPK (cat. no. 2532), rabbit polyclonal anti-human phospho-mTOR (Ser2448; cat. no. 2971), rabbit polyclonal anti-human mTOR (cat. no. 2972), rabbit polyclonal anti-human phospho-4EBP1 (Thr70; cat. no. 9455), rabbit polyclonal anti-human 4EBP1 (cat. no. 9452) and rabbit polyclonal anti-human β-actin (cat. no. 4967) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (cat. no. 7076) and anti-rabbit (cat. no. 7074; both 1:3,000) secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Super Signal® West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate was purchased from Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Cell lines and culture

Human ovary adenocarcinoma SKOV3, Caov-3 and NIH-3T3 cell lines were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank, Korean Cell Line Research Foundation (Seoul, Korea), and grown in McCoy's 5A, DMEM and RPMI-1640 media, respectively, supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2-controlled incubator.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded at 5×103 cells/ml in 96-well microplates and were cultured overnight to allow attachment. Honokiol (1-100 µM), compound C (20 µM), and AICAR (500 µM) were added to the medium. Following treatment, cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. CCK-8 (10 µl) solution was added, and cells were incubated for 3 h at 37°C. The optical density (OD) was assessed at 450 nm using a precision microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC., San Jose, CA, USA).

Soft agar colony forming assay

Cells (5×103/ml) were suspended in growth medium (3 ml) containing 0.3% agar and 10% FBS. They were then applied to pre-solidified 0.6% agar (3 ml in FBS-free growth media) in 60 mm culture dishes. After 2-3 weeks of incubation at 37°C, colonies on soft agar were observed under a phase-contrast microscope (IX2-ILL100, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of ×40.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested using Trypsin-EDTA, and washed twice in cold PBS. Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PI, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF) and placed on ice for 1 h. The supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. A Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure protein concentrations. Equal amounts of protein (50 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinyli-dene difluoride membranes. Membranes were then blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) for 1 h at 25°C to prevent nonspecific antibody binding, then incubated with caspase-3, caspase-7, caspase-9, PARP, AMPK, phospho-AMPK, mTOR, phospho-mTOR, 4EBP1, phospho-4EBP1 and β-actin primary antibodies (1:1,000) overnight at 4°C. Subsequent to washing with PBST, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibodies (both 1:3,000) at room temperature for 2 h and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence using Super Signal® West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate. Band intensity was quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software [version 1.52; National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA] and was normalized to loading controls.

Annexin V-PI double staining assay

Cells were cultured at a density of 1×106/ml and treated with honokiol and compound C for 24 h. Cells were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and then the supernatant discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml cold PBS. These cells were processed and labeled using EzWay™ Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection kit (KOMABIOTEC., Seoul, Korea). Labeled cells were then analyzed with a BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer using BD FACSDiva™ software (version 6.1.3; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Wound healing assay

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated in serum-free medium for 18 h. The cellular mono-layer was wounded with a 10 µl-pipette tip and washed with serum-free media to remove cells detached from the plates. These cells were incubated in the presence and absence of honokiol for 48-72 h in growth medium containing 10% FBS. The medium was then replaced with PBS and images of the cells were captured using a phase-contrast microscope at a magnification of ×40. Results were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.52).

Matrigel invasion assay

BD Biocoat™ Transwell Invasion Chambers were used to perform cell invasion assays. Each insert was equipped with a 6.4 mm diameter PET porous membrane (pore size=8 µm) coated for 6 h at 37°C with Matrigel Matrix (BD Biosciences). Cells (2.5×104) were suspended in serum-free medium (300 µl) with or without drugs. Cells were placed in the upper chamber while medium (500 µl) containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. Following incubation for 24 h at 37°C, non-invading cells were removed from the upper surface of the membrane, while invading cells on the lower surface of the membrane were stained with 0.1% hematoxylin for 30 min at room temperature. The membranes were then removed and light microscopy was used to count invading cells at a magnification of ×40. Results were normalized to control cells, and the relative invasion is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of migrating cells compared with the control cells.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics v.24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey's post-hoc test was used for calculating significance between different groups. Values are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effect of honokiol on ovarian cancer cell proliferation and colony formation

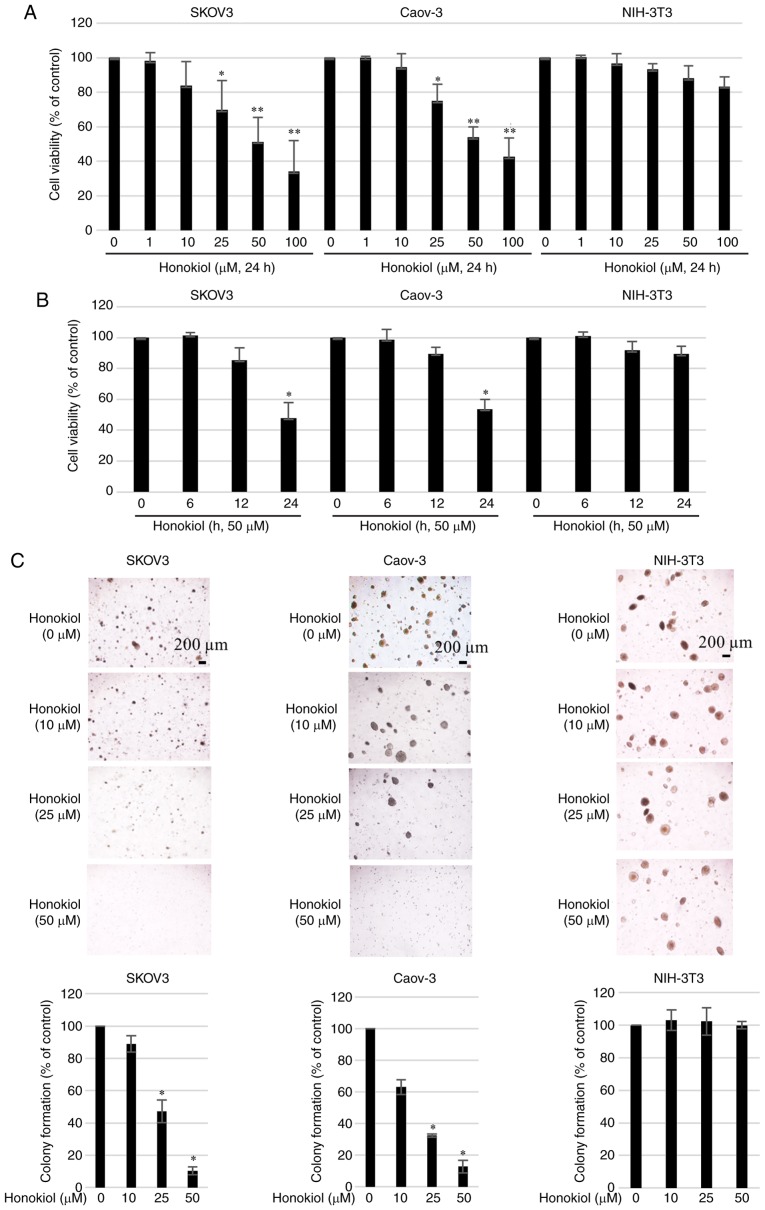

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of honokiol for ovarian cancer treatment, the human ovarian cancer SKOV3 and Caov-3 cell lines were cultured with increasing concentrations of honokiol (1-100 µM) for 24 h. Cell viability (%) was then determined by CCK-8 assay. Honokiol significantly inhibited the growth of ovarian cancer cells in a dose-(1-100 µM) and time-(6-24 h) dependent manner (Fig. 1A and B). Honokiol induced a dose-dependent decrease in the growth of ovarian cancer cells, with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 48.71±11.31 µM for SKOV3 cells and 46.42±5.37 µM for Caov-3 cells after 24 h of treatment. Honokiol also exhibited low toxicity in the non-cancer NIH-3T3 fibroblast cell line. Subsequently, the effect of honokiol on cell colony formation was investigated. Consistent with its cancer cell toxicity, honokiol inhibited the colony formation property of SKOV3 and Caov-3 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Effect of honokiol on cell viability and colony formation in ovarian cancer cell lines. Cell viability of SKOV3 and Caov-3 cells and normal cells cultured in the presence of honokiol at (A) varying concentrations (1-100 µM) and for (B) various time intervals (6-24 h) was measured using a Cell Counting kit-8 assay. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control. (C) A colony-forming assay using a single cell culture treated with honokiol at varying concentrations (10-50 µM) was performed. Cells were cultured until colonies were visible. Images represent phase-contrast microscopic examination of the morphology of cells in culture at magnification, ×40. The histograms represent the average number of colonies (in 6 fields of view). *P<0.05 vs. untreated controls. Scale bars, 200 µm.

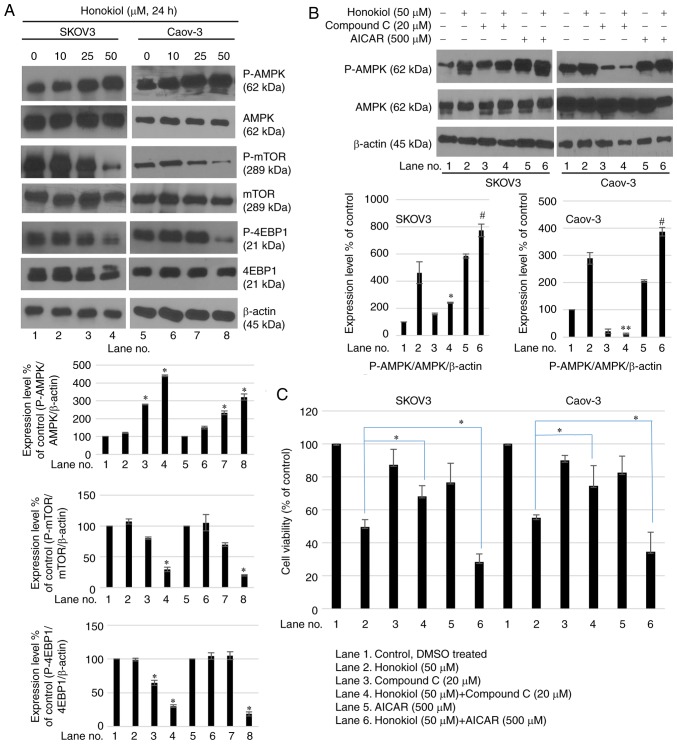

Honokiol activates AMPK in ovarian cancer cells

To additionally examine the mechanism by which honokiol induced growth inhibition of ovarian cancer cells, AMPK signaling in SKOV3 and Caov-3 cells was studied. Honokiol dose-dependently induced the phosphorylation of the Thr172 subunit of AMPK in ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 2A). Honokiol-induced AMPK activation was associated with a decreased level of phosphorylation of mTOR (Fig. 2A). To additionally confirm these changes, the AMPK inhibitor compound C was used in combination with honokiol. Compound C is a potent, selective and reversible ATP-competitive inhibitor of AMPK (inhibitor constant=109 nM in the presence of 5 µM ATP and absence of AMP). The results indicated that compound C attenuated honokiol-induced AMPK activation (Fig. 2B), and rescued ovarian cancer cells from cell growth inhibition induced by honokiol (Fig. 2C). Conversely, treatment with AMPK activator AICAR in combination with honokiol markedly induced AMPK activation (Fig. 2B) and ovarian cancer cell death (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that AMPK regulation modulated honokiol-induced cell death.

Figure 2.

Honokiol activates AMPK in ovarian cancer cells. (A) Cells were treated with honokiol (10, 25 and 50 µM) for 24 h. Total protein was isolated and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and western blot analysis was performed using specific antibodies for phosphorylated AMPK (Thr172), AMPK, phosphorylated mTOR (Ser2448) and mTOR. β-actin was used as a loading control. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. the untreated control. (B) Cells were treated with honokiol (50 µM) for 24 h, then with compound C (20 µM) or AICAR (500 µM) prior to honokiol stimulation. Western blot analysis was performed to determine protein expression levels of phosphorylated AMPK (Thr172) and AMPK. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. honokiol-only treatment (lane 2). #P<0.05 vs. honokiol single treatment (lane 2). (C) Following pre-treatment with compound C (20 µM) or AICAR (500 µM), cells were treated with honokiol (50 µM) for 24 h. A CCK-8 assay was used to determine cell viability. Data are presented as a percentage of the control. *P<0.05 vs. honokiol-only treatment. p, phosphorylated; AMPK, adenosine 5′-phosphate-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; AICAR, aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide.

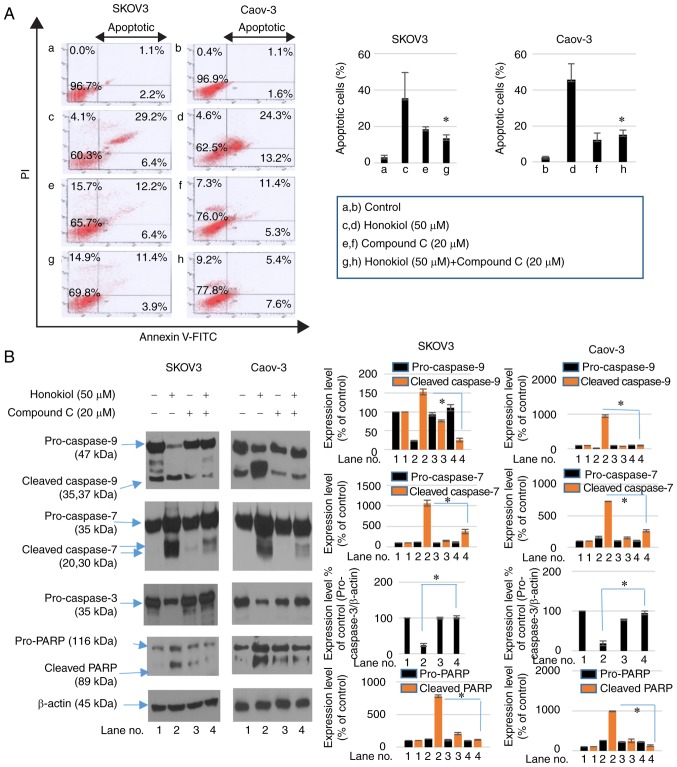

Honokiol induces apoptosis via AMPK activation in ovarian cancer cells

To examine whether the induction of apoptosis contributed to the honokiol-mediated decrease in cell viability of ovarian cancer cells, Annexin V-FITC/PI staining was performed to analyze the population of apop-totic cells. Treatment with honokiol for 24 h increased the population of apoptotic cells. However, compound C treatment with honokiol decreased Annexin V/PI-positive cell numbers (Fig. 3A). The mechanism involved in apoptotic cell death induced by honokiol treatment was then investigated. SKOV3 and Caov-3 cells were treated with honokiol and compound C for 24 h. Western blot analysis was used to analyze the activation of caspase-3, caspase-7, caspase-9, and cleavage of PARP. Following treatment with honokiol, activation of caspase-3, -7, and -9 and increased cleavage of PARP were observed. However, treatment with compound C in combination with honokiol attenuated the activation of caspase-3, -7 and -9, and increased cleavage of PARP induced by honokiol alone (Fig. 3B). Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry also revealed an accumulation of sub-G0/G1 cells following honokiol treatment, while treatment with compound C decreased the proportion of sub-G0/G1 cells (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that honokiol-induced apoptosis was involved in its AMPK-mediated anticancer activity.

Figure 3.

Honokiol induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. (A) Cells were pre-treated with compound C for 2 h prior to treatment with honokiol (50 µM). An Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining flow cytometry assay was used to measure apoptotic cells. (A-a) Control treatment in SKOV3 cells. (A-b) Control treatment in the Caov-3 cells. (A-c) Honokiol treatment (50 µM) in SKOV3 cells. (A-d) Honokiol treatment (50 µM) in Caov-3 cells. (A-e) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells. (A-f) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells. (A-g) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells. (A-h) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells. Data in the graph are representative of 3 independent experiments. The percentages of apoptotic cells are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. single honokiol treatment. (B) Cells were treated with compound C (20 µM) prior to stimulation by honokiol (50 µM) for 24 h. Western blot analysis determined the caspase-3, caspase-7, caspase-9 and PARP protein expression levels. β-actin was used as an internal control. *P<0.05 vs. honokiol-only treatment. (C) Flow cytometry analysis examined the effects of honokiol (50 µM) and compound C (20 µM) on cell cycle distribution. (C-a) Control treatment in SKOV3 cells. (C-b) Honokiol treatment (50 µM) in SKOV3 cells. (C-c) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells. (C-d) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells. (C-e) Control treatment in the Caov-3 cells. (C-f) Honokiol treatment (50 µM) in Caov-3 cells. (C-g) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells. (C-h) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. honokiol-only treatment. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PI, propidium iodide; PARP, poly-(adenosine 5′-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase.

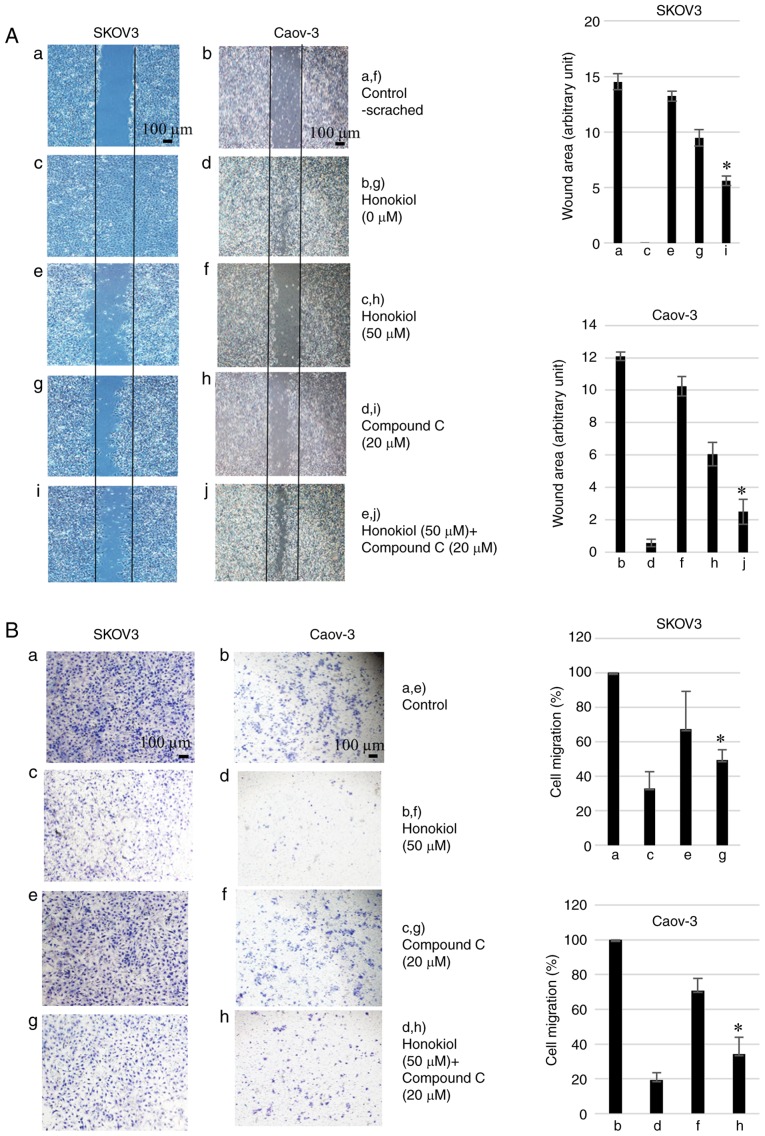

Honokiol inhibits migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells

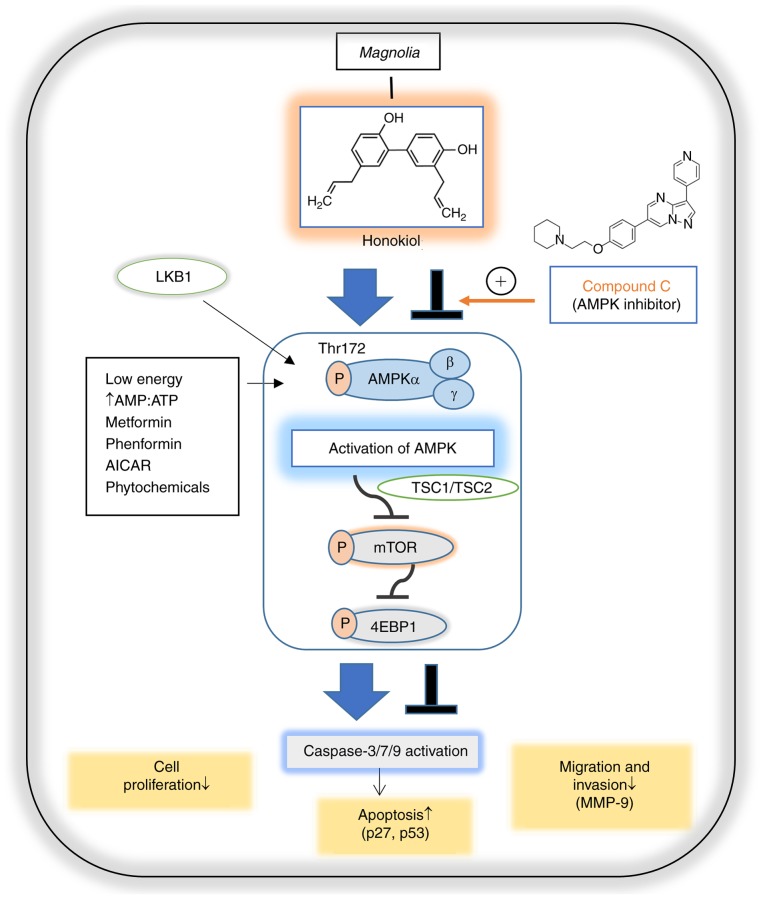

To determine whether honokiol impaired the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells, SKOV3 and Caov-3 were subjected to honokiol treatment. Wound healing assays indicated that honokiol treatment significantly inhibited the migration distance between the leading edge of cells. However, compound C reversed this activity (Fig. 4A). The Matrigel invasion assays demonstrated that treatment with 50 µM honokiol resulted in a 66.9 and 80.7% decrease in migration of SKOV3 and Caov-3 cells, respectively, compared with the untreated cells. The decrease in Matrigel invasion induced by honokiol was significantly reversed by compound C treatment (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that honokiol-induced AMPK activation inhibited the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Based on the results of the present study, the potential biological activities of honokiol are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 4.

Honokiol inhibits ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion. (A) Cells were cultured until a monolayer was formed, which was then scratched with a pipette tip. Images of wounds at 0 h were captured. After 48 h (SKOV3) or 72 h (Caov-3) incubation, plates were observed with a phase-contrast microscope at magnification, ×40. The area without cells was measured by ImageJ software in arbitrary units. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (A-a) Control treatment in SKOV3 cells at 0 h. (A-b) Control treatment in the Caov-3 cells at 0 h. (A-c) Honokiol treatment (0 µM) in SKOV3 cells at 48 h. (A-d) Honokiol treatment (0 µM) in Caov-3 cells at 72 h. (A-e) Honokiol (50 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells at 48 h. (A-f) Honokiol (50 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells at 72 h. (A-g) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells at 48 h. (A-h) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells at 72 h. (A-i) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells at 48 h. (A-j) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells at 72 h. *P<0.05 vs. honokiol-only treatment (e and f). Scale bars, 100 µm. (B) Cells treated with honokiol (50 µM) and/or compound C (20 µM) were plated onto the upper part of the Matrigel invasion chamber. After 48 h (SKOV3) or 72 h (Caov-3) incubation, invasive cells that had migrated to the lower part of the membrane were stained with trypan blue and observed using a phase-contrast microscope at magnification, ×40. (B-a) Control treatment in SKOV3 cells. (B-b) Control treatment in the Caov-3 cells. (B-c) Honokiol treatment (50 µM) in SKOV3 cells. (B-d) Honokiol treatment (50 µM) in Caov-3 cells. (B-e) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells. (B-f) Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells. (B-g) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in SKOV3 cells. (B-h) Honokiol (50 µM) + Compound C (20 µM) treatment in Caov-3 cells. *P<0.05 vs. honokiol-only treatment (c and d). Scale bars, 100 µm.

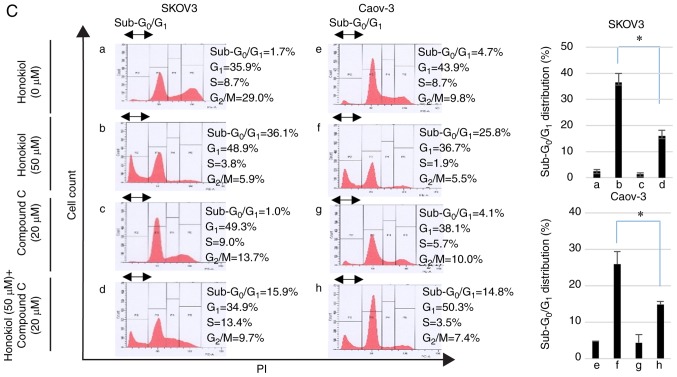

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of AMPK-dependent anticancer activities of honokiol in ovarian cancer cells. AMPK is activated in response to cellular energy stress by sensing increasing AMP/ATP ratio, leading to the activation of LKB1. Metformin, phenformin, AICAR and phytochemicals may also mimic stressors and lead to AMPK activation in an LKB1-dependent manner. A specific AMPK pathway involves the TSC1/TSC2 complex, leading to the downregulation of mTOR, which regulates apoptosis, cell growth, migration and invasion. The mTOR pathway inhibits apoptosis via the regulation of the tumor suppressors p27 and p53. The mTOR/4EBP1 pathway regulates cell migration by regulating MMP-9. Honokiol activates AMPK, which inhibits mTOR/4EBP1 signaling, leading to anti-proliferative effects and apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Honokiol also inhibits migration and invasion via AMPK activation. The AMPK inhibitor compound C reverses honokiol-regulated proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion. Blue arrows indicate activation, T-bars indicate downregulation. AMP, adenosine 5′-phosphate; ATP, adenosine 5′-triphosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; LKB1, liver kinase B1; AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carbox-amide ribonucleotide; TSC1, tuberous sclerosis 1 protein; TSC2, tuberous sclerosis 2 protein; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; 4EBP1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; p27, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B; p53, tumor protein p53.

Discussion

Honokiol has generated increasing interest in cancer studies, due to its multi-functional effects, including its anticancer, anti-angiogenesis and anti-migration properties, which have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo using preclinical models (30). Previous studies have demonstrated that honokiol may induce growth inhibition and apoptosis in various types of cancer, including lung, breast, colon and prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo (31-34). The present study demonstrated that honokiol induced cytotoxicity and inhibited proliferation in the ovarian cancer SKOV3 and Caov-3 cell lines, whereas the normal NIH-3T3 cell line exhibited low cytotoxicity. These results are consistent with a previous study that revealed that the IC50 values of honokiol at 24 h for SKOV3, Coc 1, Angelen and A2780 cells were 16.7, 19.6, 16.4, and 14.9 µg/ml, respectively (35).

Previous studies have suggested that the upstream kinases of AMPK, including liver kinase B1 (LKB1), are frequently mutated and deleted in human cancer (36-38). Genetic deletion of the LKB1 gene results in a loss of AMPK activity that represents a common event in cancer cell growth (39). Being directly activated by the tumor suppressor LKB1, AMPK regulates the activation of 2 other tumor suppressors, TSC1 and TSC2, which are critical regulators of mTOR (40). AMPK-initiated mTOR inhibition suppresses downstream effectors p70S6K and 4EBP1, regulating transcription, translation, protein stability, mRNA turnover and cell size (40,41). Previous studies have demonstrated that several AMPK activators, mTOR inhibitors and their combination, including metformin, AICAR or rapamycin, may suppress cancer cell growth (42-47). Therefore, AMPK is an essential target for cancer therapy.

Honokiol targets multiple signaling pathways including epidermal growth factor receptor, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells B, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, and mTOR, which serve essential roles in cancer initiation and progression (48). Previous data have suggested that honokiol affects melanoma and breast cancer cell growth by targeting AMPK signaling (28,49). However, whether AMPK targeting via honokiol is the cause its anticancer effects in ovarian cancer is unclear. In the present study, activation of AMPK in honokiol-treated ovarian cancer cells was observed, which may have contributed to the cell death pathway.

As honokiol has demonstrated inhibitory effects on the viability of human ovarian cancer cells, the present study examined whether it modulated cell cycle progression and induced apoptotic cell death in the same manner as AMPK activation. The results indicated that honokiol may lead to the caspase-dependent apoptotic death of ovarian cancer cells, causing an increase in the sub-G1 population of apoptotic cells. Induction of apoptosis was indicated by the elevated expression of apoptotic markers, including activation of caspase-3, caspase-7 and caspase-9, and cleavage of PARP. These characteristics of apoptosis were inhibited by compound C, a pharmacological inhibitor of AMPK. Previous studies have suggested that AMPK activation may induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in various types of cancer, including breast, colon and oral cancer (50-52). Therefore, honokiol may induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells through AMPK activation.

Previous studies have revealed that the activation of AMPK by metformin not only inhibits cell proliferation, but also decelerates cell migration (53). Honokiol suppresses metastasis by inhibiting cell migration in neuroblastoma (25), and breast (29), and renal cancer (54). However, to the best of our knowledge, honokiol-induced metastatic activity on ovarian cancer has never been investigated. To address the functional role of honokiol in ovarian cancer metastasis, the present study examined the anti-metastatic effect of honokiol on ovarian cancer cells. It was identified that AMPK activation by honokiol treatment suppressed cell migration and the invasive properties of ovarian cancer cells. These results suggested that honokiol may be a potential therapeutic target for treating metastatic ovarian cancer.

In summary, honokiol, a natural compound, exhibited anticancer activities against the ovarian cancer SKOV3 and Caov-3 cell lines. Honokiol significantly suppressed cell proliferation and induced apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells by activating AMPK. Honokiol also inhibited their metastatic and invasive activities, potentially through AMPK activation. Although honokiol has been implicated in AMPK signaling in other cancer types, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the role of AMPK in ovarian cancer. The results indicated that honokiol has potential clinical application for preventing and treating ovarian cancer.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a research fund of Chungnam National University (grant no. 2016168601).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

JSL designed the study and prepared the manuscript. JBP, MSL and EYC performed experiments and analyzed the data. JYS and YBK were involved in the study conception and design, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hoskins WJ, McGuire WP, Brady MF, Homesley HD, Creasman WT, Berman M, Ball H, Berek JS. The effect of diameter of largest residual disease on survival after primary cytoreductive surgery in patients with suboptimal residual epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:974–979. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(94)70090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Chen L, He X, Fan L, Yang G, Chen X, Lin X, DU L, Li Z, Ye H, et al. Enhancement of therapeutic effectiveness by combining liposomal honokiol with cisplatin in ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson D, Burger RA, Mannel RS, DeGeest K, Hartenbach EM, Baergen R, Gynecologic Oncology Group Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: A gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardie DG. Sensing of energy and nutrients by AMP-activated protein kinase. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:891S–896S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JL, Stanford JL. Metformin use and prostate cancer in caucasian men: Results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1617–1622. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson D, Frieson D, Zuber J, Solomon SS. Metformin has positive therapeutic effects in colon cancer and lung cancer. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodmer M, Meier C, Krähenbühl S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Long-term metformin use is associated with decreased risk of breast cancer. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1304–1308. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li D, Yeung SC, Hassan MM, Konopleva M, Abbruzzese JL. Antidiabetic therapies affect risk of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:482–488. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowling RJ, Zakikhani M, Fantus IG, Pollak M, Sonenberg N. Metformin inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent translation initiation in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10804–10812. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang LW, Li ZS, Zou DW, Jin ZD, Gao J, Xu GM. Metformin induces apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7192–7198. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He XX, Tu SM, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Thiazolidinediones and metformin associated with improved survival of diabetic prostate cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2640–2645. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiralerspong S, Palla SL, Giordano SH, Meric-Bernstam F, Liedtke C, Barnett CM, Hsu L, Hung MC, Hortobagyi GN, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Metformin and pathologic complete responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in diabetic patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3297–3302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.19.6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: An update. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:25–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zong H, Yin B, Zhou H, Cai D, Ma B, Xiang Y. Inhibition of mTOR pathway attenuates migration and invasion of gallbladder cancer via EMT inhibition. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:4507–4512. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoki K, Kim J, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:381–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapuis N, Tamburini J, Green AS, Willems L, Bardet V, Park S, Lacombe C, Mayeux P, Bouscary D. Perspectives on inhibiting mTOR as a future treatment strategy for hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2010;24:1686–1699. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Wang S, Zhang Y, Fan HT, Lin HS. Traditional chinese medicine and cancer: History, present situation, and development. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:561–569. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo MS, Hong SW, Yeon SH, Kim YM, Um KA, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Chang KC, Park SW. Magnolia officinalis attenuates free fatty acid-induced lipogenesis via AMPK phosphorylation in hepatocytes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Zhang X, Cui W, Zhang X, Li N, Chen J, Wong AW, Roberts A. Evaluation of short-term and subchronic toxicity of magnolia bark extract in rats. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;49:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarrica A, Kirika N, Romeo M, Salmona M, Diomede L. Safety and toxicology of magnolol and honokiol. Planta Med. 2018;84:1151–1164. doi: 10.1055/a-0642-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried LE, Arbiser JL. Honokiol, a multifunctional antiangiogenic and antitumor agent. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1139–1148. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinmann P, Walters DK, Arlt MJ, Banke IJ, Ziegler U, Langsam B, Arbiser J, Muff R, Born W, Fuchs B. Antimetastatic activity of honokiol in osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2012;118:2117–2127. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park EJ, Min HY, Chung HJ, Hong JY, Kang YJ, Hung TM, Youn UJ, Kim YS, Bae K, Kang SS, Lee SK. Down-regulation of c-Src/EGFR-mediated signaling activation is involved in the honokiol-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa C, Arbiser JL, Mori N. Honokiol induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via inhibition of survival signals in adult T-cell leukemia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:879–887. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh PS, Wang W, Chang YA, Lin CJ, Wang JJ, Chen RM. Honokiol induces autophagy of neuroblastoma cells through activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and endoplasmic reticular stress/ERK1/2 signaling pathways and suppressing cell migration. Cancer Lett. 2016;370:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai X, Li RZ, Jiang ZB, Wei CL, Luo LX, Yao XJ, Li GP, Leung EL. Honokiol inhibits proliferation, invasion and induces apoptosis through targeting lyn kinase in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:558. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L, Zhang F, Huang R, Yan J, Shen B. Honokiol inhibits bladder cancer cell invasion through repressing SRC-3 expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:4294–4300. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagalingam A, Arbiser JL, Bonner MY, Saxena NK, Sharma D. Honokiol activates AMP-activated protein kinase in breast cancer cells via an LKB1-dependent pathway and inhibits breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R35. doi: 10.1186/bcr3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh T, Katiyar SK. Honokiol, a phytochemical from magnolia spp., inhibits breast cancer cell migration by targeting nitric oxide and cyclooxygenase-2. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:769–776. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Kumar Singh U, Chaudhary A. Honokiol analogs: A novel class of anticancer agents targeting cell signaling pathways and other bioactivities. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:809–829. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo LX, Li Y, Liu ZQ, Fan XX, Duan FG, Li RZ, Yao XJ, Leung EL, Liu L. Honokiol induces apoptosis, G1 arrest, and autophagy in KRAS mutant lung cancer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:199. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shigemura K, Arbiser JL, Sun SY, Zayzafoon M, Johnstone PA, Fujisawa M, Gotoh A, Weksler B, Zhau HE, Chung LW. Honokiol, a natural plant product, inhibits the bone metastatic growth of human prostate cancer cells. Cancer. 2007;109:1279–1289. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Zang C, Emde A, Planas-Silva MD, Rosche M, Kühnl A, Schulz CO, Elstner E, Possinger K, Eucker J. Anti-tumor effect of honokiol alone and in combination with other anticancer agents in breast cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;591:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng N, Xia T, Han Y, He QJ, Zhao R, Ma JR. Synergistic antitumor effects of liposomal honokiol combined with cisplatin in colon cancer models. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:957–962. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Z, Liu Y, Zhao X, Pan X, Yin R, Huang C, Chen L, Wei Y. Honokiol, a natural therapeutic candidate, induces apoptosis and inhibits angiogenesis of ovarian tumor cells. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;140:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwan HT, Chan DW, Cai PC, Mak CS, Yung MM, Leung TH, Wong OG, Cheung AN, Ngan HY. AMPK activators suppress cervical cancer cell growth through inhibition of DVL3 mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gurumurthy S, Hezel AF, Sahin E, Berger JH, Bosenberg MW, Bardeesy N. LKB1 deficiency sensitizes mice to carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:55–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Liu Y, Zhou Y, You H. Molecular mechanism of LKB1 in the invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:1035–1044. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Lopez-Bonet E, Menendez JA. AMPK: Evidence for an energy-sensing cytokinetic tumor suppressor. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3679–3683. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.9905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardie DG. The AMP-activated protein kinase pathway-new players upstream and downstream. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5479–5487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duan P, Hu C, Quan C, Yu T, Huang W, Chen W, Tang S, Shi Y, Martin FL, Yang K. 4-Nonylphenol induces autophagy and attenuates mTOR-p70S6K/4EBP1 signaling by modulating AMPK activation in sertoli cells. Toxicol Lett. 2017;267:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zakikhani M, Dowling R, Fantus IG, Sonenberg N, Pollak M. Metformin is an AMP kinase-dependent growth inhibitor for breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10269–10273. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Moujahed A, Nicolaou F, Brodowska K, Papakostas TD, Marmalidou A, Ksander BR, Miller JW, Gragoudas E, Vavvas DG. Uveal melanoma cell growth is inhibited by aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) partially through activation of AMP-dependent kinase. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4175–4185. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yung MM, Chan DW, Liu VW, Yao KM, Ngan HY. Activation of AMPK inhibits cervical cancer cell growth through AKT/FOXO3a/FOXM1 signaling cascade. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:327. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whang YM, Kim MJ, Cho MJ, Yoon H, Choi YW, Kim TH, Chang IH. Rapamycin enhances growth inhibition on urothelial carcinoma cells through LKB1 deficiency-mediated mitochondrial dysregulation. J Cell Physiol. 2018:1–14. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang JW, Zhao F, Sun Q. Metformin synergizes with rapamycin to inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:1811–1816. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukhopadhyay S, Chatterjee A, Kogan D, Patel D, Foster DA. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-4-ribofura noside (AICAR) enhances the efficacy of rapamycin in human cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:3331–3339. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1087623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora S, Singh S, Piazza GA, Contreras CM, Panyam J, Singh AP. Honokiol: A novel natural agent for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:1244–1252. doi: 10.2174/156652412803833508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaushik G, Kwatra D, Subramaniam D, Jensen RA, Anant S, Mammen JM. Honokiol affects melanoma cell growth by targeting the AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Am J Surg. 2014;208:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Queiroz EA, Puukila S, Eichler R, Sampaio SC, Forsyth HL, Lees SJ, Barbosa AM, Dekker RF, Fortes ZB, Khaper N. Metformin induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest mediated by oxidative stress, AMPK and FOXO3a in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buzzai M, Jones RG, Amaravadi RK, Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Zhao F, Viollet B, Thompson CB. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shin JA, Kwon KH, Cho SD. AMPK-activated protein kinase activation by Impatiens balsamina L. is related to apoptosis in HSC-2 human oral cancer cells. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11:136–142. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.149728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferla R, Haspinger E, Surmacz E. Metformin inhibits leptin-induced growth and migration of glioblastoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:1077–1081. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng S, Castillo V, Eliaz I, Sliva D. Honokiol suppresses metastasis of renal cell carcinoma by targeting KISS1/KISS1R signaling. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:2293–2298. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.