Abstract

Background We designed a survey to ascertain the current perspectives of hand surgeons on the evaluation and management of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow. The secondary aim was to assess the concordance of hand surgeons on definitions of the terms “subluxated” and “dislocated” for classification of ulnar nerve instability.

Methods A questionnaire, including demographic practice variables, cubital tunnel practice patterns, preoperative imaging and electrodiagnostic evaluation, and a series of standardized intraoperative photographs of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow were developed and distributed to the current American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) membership.

Results A total of 690 (26.8%) members completed the survey; 84.2% of respondents indicated that they evaluate for ulnar nerve instability preoperatively with clinical examination, whereas only 6.1% indicated they routinely obtained dynamic ultrasound. Respondents indicated that the factors most strongly influencing their decision to proceed with anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve were subluxation on physical examination (89.6%), history consistent with ulnar nerve subluxation (85.8%), and muscle atrophy (43.2%). On review of clinical photographs, respondents demonstrated varying degrees of agreement on the terms “subluxated” or “dislocated” and recommendations for ulnar nerve transposition at intermediate degrees of ulnar nerve instability.

Conclusion ASSH members routinely evaluate for ulnar nerve instability with history and clinical examination without uniform use of preoperative ultrasound, and nearly half of the time the decision to transpose the ulnar nerve is made intraoperatively. Definitions for the degree of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow are not uniformly agreed upon, and further development of a classification system may be warranted to standardize treatment.

Keywords: anterior transposition of ulnar nerve, cubital tunnel syndrome, ulnar nerve instability, ulnar nerve, perspective of hand surgeons

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common upper extremity entrapment neuropathy following carpal tunnel syndrome. 1 Operative management of ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow consists of “in situ” decompression with or without anterior ulnar nerve transposition, endoscopic decompression, or medial epicondylectomy, and optimal operative management of cubital tunnel syndrome remains controversial. 2 Advocates of in situ decompression alone contend that areas of focal compression are released without threatening the vascularity of the nerve, whereas advocates of anterior transposition contend that transposition directly addresses both compressive and traction mechanisms of nerve injury. 2 One of the key determinants of operative procedure selection is ulnar nerve stability or lack thereof at the elbow. 3 Proponents of anterior transposition argue that a hypermobile nerve is best addressed with anterior transposition which provides stability and places the nerve along the shortest path to prevent further traction injury. 2

Ulnar nerve instability at the elbow is not uncommon and has been reported to be present in up to 47% of asymptomatic individuals. 4 Despite its high prevalence, definitions for ulnar nerve instability are not uniformly applied. Childress classified ulnar nerve instability as Type A or “complete” for nerves that are transposed over the medial epicondyle and Type B or “incomplete” for nerves that rest upon the medial epicondyle. 5 Richard et al recommended adding an additional group to Childress' classification, “hypermobility,” in which a nerve located within the groove can be intraoperatively transposed over the tip of the medial epicondyle and will remain in that position throughout elbow range of motion. 6 Calfee et al referred to a nerve which can be subluxated from the groove on physical examination as “perchable.” 4 Richard et al defined ulnar nerve “subluxation” as movement of the nerve out of the postcondylar groove onto or across the tip of the medial humeral condyle when the elbow is flexed and returning to its normal location when the elbow is extended. 6 Okamoto et al proposed a dynamic ultrasound classification for ulnar nerve instability, where nerves which moved anteriorly but not to the tip of the epicondyle were termed “not dislocated or subluxated,” nerves which transposed to the tip of the medial epicondyle but not beyond were termed “subluxated,” and nerves which transposed anterior to the tip of the epicondyle as “dislocated.” These patterns of instability occurred in 54, 27, and 19% of asymptomatic patients, respectively. 7 ”Subluxated” or “dislocated” ulnar nerves are identified in 20 to 25% of patients with ulnar neuropathy at the elbow either pre- or intraoperatively. 3 8 9

The presence of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow is not a uniformly accepted predisposing factor to the development of ulnar neuropathy. Some authors propose that ulnar nerve instability places the ulnar nerve in a relatively vulnerable position with altered excursion during flexion and extension subjecting it to greater stretch and compressive forces, culminating in the development of ulnar neuritis and perineural scarring. 2 8 However, others have noted the high incidence of ulnar nerve instability in the asymptomatic population and that its positive predictive value for ulnar neuropathy cannot be determined. 4 9 10 At present, there is a dichotomy between traditional surgical teaching and the evidence base regarding ulnar nerve instability, with the evidence supporting in situ decompression for luxation of the ulnar nerve 3 9 11 12 and traditional teaching favoring anterior transposition to reduce the potential for persistent or recurrent symptoms as well as ulnar nerve instability following decompression. 13

Given the lack of consensus on the definitions of ulnar nerve instability as well as the impact of this phenomenon on operative decision making, the purpose of this study was to solicit opinions on current trends and common practices among hand surgeons regarding the diagnosis and treatment of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow. The secondary purpose of the study was to identify if common terminology for defining ulnar nerve stability at the elbow exists among hand surgeons, and whether this terminology has a bearing on treatment recommendations.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a short questionnaire was approved by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) Research Committee and permission was obtained for distribution to the members of the ASSH ( n = 2,573) during the months of January and February 2017. Participants received an invitation to participate in the survey via electronic mailing followed by one reminder e-mail 2 weeks later. The mailing contained a link to the survey. The survey was hosted by our Survey Research Center, which allowed both the administration of the questions and standardized images, and collection of the data electronically. Duplicate and incorrectly answered surveys were excluded.

Demographic questions included the practice type, specialty training, years in practice, and percentage of practice devoted to hand surgery. Questions pertaining to practice patterns regarding cubital tunnel management included the number of operative cases performed per year, method of preoperative assessment of ulnar nerve instability, and the frequency of operations performed for primary cubital tunnel syndrome with and without muscle weakness. Questions examining decision-making processes regarding anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve included the time point for the decision to perform anterior transposition, frequency of operations performed for the management of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow, and the factors associated with the decision to proceed with and the depth of anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve.

For assessment of the respondents' ability to classify ulnar nerve instability at the elbow, a series of standardized photographs were developed. The ulnar nerve of a cadaveric shoulder to fingertip specimen without a history of prior elbow or ulnar nerve pathology was released 10 cm proximal and distal to the medial epicondyle. Photographs were taken in elbow extension and flexion with the nerve situated in its native location. The ulnar nerve was then serially transposed anteriorly in 2 mm intervals and photographed followed by a final image with the ulnar nerve anteriorly transposed by 2 cm, thereby creating a series of simulated ulnar nerve instability. The series was then randomized and included in the survey. Respondents were asked if the photographs demonstrated a “subluxated” or “dislocated” ulnar nerve as well as their likelihood to proceed with anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve for the degree of demonstrated ulnar nerve instability. For further information, please refer to the Supplementary Material for detailed questionnaire (available in the online version).

Five-point Likert scales were developed with the assistance of our department of statistics to facilitate compression for data tabulation and utilized for data collection. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data, including percentages and counts for categorical and ordinal data, and means and standard error for continuous data. Differences between groups were compared with the chi-square test (or Fischer's exact test) for categorical variables. A p -value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The questionnaires were sent to a total of 2,573 eligible ASSH members, and 690 (26.8%) completed the survey. The majority of respondents were orthopaedic (79.1%) or plastic (15.4%) surgeons, with 71.2% of respondents holding a Subspecialty Certificate in Surgery of the Hand (SOTH) ( Table 1 ). With regard to practice dynamics, respondents were fairly balanced with respect to academic (40.7%) versus nonacademic (49.9%) practice with the majority being in practice for more than 10 years following residency training (43.8%).

Table 1. Demographics and cubital tunnel management.

| Demographics | ||||

| Subspecialty Certificate in Surgery of the Hand | 71.2% | |||

| Practice type | ||||

| Academic | 40.7% | |||

| Nonacademic | 49.9% | |||

| Group practice | 79.0% | |||

| Solo practice | 13.2% | |||

| Specialty training | ||||

| Orthopaedic surgery | 79.1% | |||

| Plastic surgery | 15.4% | |||

| General surgery | 3.4% | |||

| Years in practice | ||||

| Less than 10 y | 37.0% | |||

| 10–20 y | 19.2% | |||

| More than 10 y | 43.8% | |||

| % of practice devoted to hand | ||||

| Less than 50 | 7.9% | |||

| 50–75 | 18.6% | |||

| More than 75 | 73.5% | |||

| Cubital tunnel management | ||||

| Operative cases of cubital tunnel per year | ||||

| Less than 10 | 22.5% | |||

| 10–25 | 40.0% | |||

| 26–50 | 28.8% | |||

| More than 50 | 8.7% | |||

| Preoperative assessment of ulnar nerve instability | ||||

| Clinical examination | 84.1% | |||

| Ultrasound | 0.8% | |||

| Clinical examination and ultrasound | 6.3% | |||

| Intraoperative examination | 6.7% | |||

| Clinical examination and intraoperative examination | 1.8% | |||

| Percentage of the time respondents perform the following operations for primary cubital tunnel syndrome without muscle weakness in their practice (expressed as percentage of respondents) | ||||

| >51% | 26–50% | <25% | Never | |

| In situ decompression | 68.7% | 8.3% | 14.1% | 8.9% |

| Endoscopic-assisted decompression | 7.5% | 1.9% | 11.3% | 79.3% |

| Medial epicondylectomy | 2.3% | 2.9% | 29.5% | 65.3% |

| Anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve | 26.5% | 19.7% | 50.5% | 3.3% |

| Percentage of the time respondents perform the following operations for primary cubital tunnel syndrome with muscle weakness in their practice (expressed as percentage of respondents) | ||||

| >51% | 26–50% | <25% | Never | |

| In situ decompression | 55.2% | 11.7% | 22.6% | 10.6% |

| Endoscopic-assisted decompression | 6.2% | 1.9% | 10.5% | 81.6% |

| Medial epicondylectomy | 2.8% | 3.5% | 28.8% | 64.9% |

| Anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve | 44.5% | 21.0% | 32.6% | 2.0% |

Regarding the management of cubital tunnel syndrome ( Table 1 ), the majority of respondents performed 10 to 25 operative cases annually (40.0%). The majority of respondents evaluated ulnar nerve instability with clinical examination alone (84.1%). Preoperative dynamic ulnar nerve ultrasound was used by 7.1% of respondents (6.3% clinical examination and ultrasound; 0.8% ultrasound alone). For the management of primary cubital tunnel syndrome without muscle weakness, 68.7% of respondents performed in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve in the majority of cases, whereas 26.5% of respondents performed an anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. For the management of primary cubital tunnel syndrome with muscle weakness, the majority of respondents (55.2%) still would perform in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve most commonly. However, in the presence of muscle weakness, more respondents would perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve (44.5% with weakness vs. 26.5% without weakness). Overall endoscopic decompression and medial epicondylectomy were less commonly performed.

With respect to decision making for anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve, 41.6% of respondents made this decision more than half of the time preoperatively versus 32.2% of respondents doing this intraoperatively ( Table 2 ). A preoperative decision to proceed with anterior transposition was significantly associated with a having a SOTH ( p < 0.01), academic practice ( p < 0.01), and the use of preoperative ultrasound ( p < 0.05). Subcutaneous transposition (57.9%) was performed most commonly for primary cubital tunnel syndrome with ulnar nerve instability. The majority of respondents agreed that the decision to proceed with anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve was influenced by ulnar subluxation on physical examination (89.6%), history consistent with subluxation (85.8%), and the presence of muscle atrophy (43.2%), whereas only 12.6% of respondents are influenced by preoperative ultrasound findings. Academic practice was the only demographic factor investigated which was significantly associated with the use of preoperative ultrasound ( p < 0.01). The most commonly identified factors that influenced transposition depth included the amount and quality of subcutaneous tissue (60.6%) and concerns regarding the need for secondary surgery (48.9%).

Table 2. Anterior transposition decision making.

| Percentage of the time respondents decide to perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve pre- versus postoperatively (expressed as percentage of respondents) | ||||

| >51% | 26–50% | <25% | Never | |

| Preoperative | 41.6% | 18.0% | 36.0% | 4.4% |

| Intraoperative | 32.2% | 21.5% | 39.9% | 6.5% |

| Percentage of the time respondents perform the following operations for primary cubital tunnel syndrome with ulnar nerve instability in their practice (expressed as percentage of respondents) | ||||

| >51% | 26–50% | <25% | Never | |

| In situ decompression | 11.1% | 4.7% | 61.9% | 22.2% |

| Subcutaneous anterior transposition | 57.9% | 11.8% | 21.6% | 8.7% |

| Intramuscular anterior transposition | 16.1% | 8.8% | 36.1% | 39.0% |

| Submuscular anterior transposition | 18.6% | 12.2% | 47.6% | 21.6% |

| Factors influencing decision to proceed with anterior transposition of ulnar nerve | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | |

| Ulnar nerve subluxation on physical examination | 89.6% | 5.9% | 4.5% | |

| History consistent with ulnar nerve subluxation | 85.8% | 9.4% | 4.9% | |

| Presence of muscle atrophy | 43.2% | 29.2% | 27.6% | |

| Preoperative EMG and NCS | 31.4% | 32.9% | 35.6% | |

| Preoperative ultrasound | 12.6% | 46.2% | 41.3% | |

| Factors influencing transposition depth of ulnar nerve | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | |

| Amount and quality of subcutaneous tissue | 60.6% | 19.7% | 19.7% | |

| Concern for need for secondary surgery | 48.9% | 26.3% | 24.8% | |

| Severity and grade of cubital tunnel syndrome | 30.1% | 29.5% | 40.5% | |

| Residency or fellowship training | 28.5% | 32.0% | 39.6% | |

| Patient demographics | 18.4% | 32.1% | 49.6% | |

Abbreviations: EMG, electromyography; NCS, nerve conduction studies.

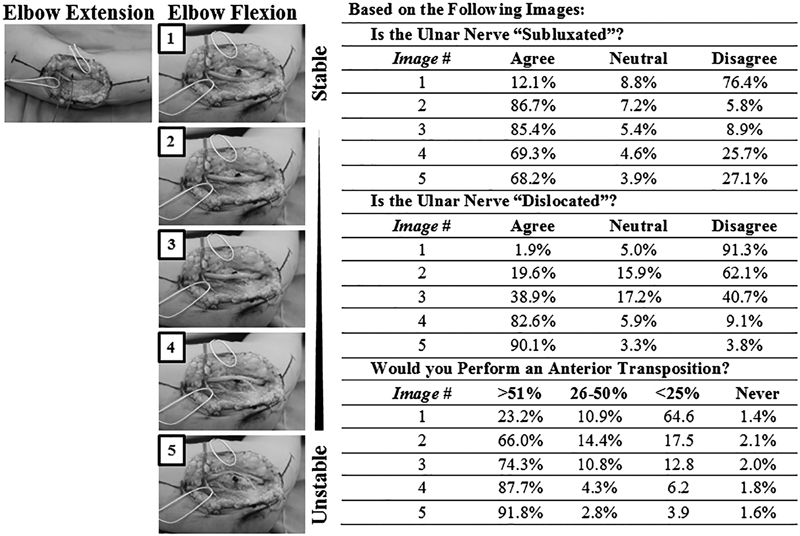

On review of the standardized photographs, respondents correctly identified a “normal” ulnar nerve as not “dislocated” (91.3%) and not “subluxated” (76.4%), with the majority recommending against anterior transposition ( Fig. 1 ). With simulated anterior translocation of the ulnar nerve in flexion, the respondents demonstrated concordance on the terms “subluxated” or “dislocated,” and the majority recommended anterior transposition with simulated “subluxation” or “dislocation.” The majority of respondents identified the photographs with 2 and 4 mm anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve in photographs 2 and 3 as “subluxated” (86.7 and 85.4%, respectively). The majority of respondents identified photographs 4 and 5 as “dislocated” (82.6 and 90.1%, respectively). The majority of surgeons would perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve, which they identified as either “subluxated” or “dislocated” ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Photographic simulation of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow. (Left panel) Standardize photographs following in situ decompression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow in extension, and with varying degrees of simulated ulnar nerve “instability” with sequential anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve (dark gray vessel loop). The medial epicondyle tip is indicated with ink dot marking. The data for identification of the nerve as “subluxated,” “dislocated,” and the likelihood of respondents to perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve are presented (right panel).

Discussion

Given the disparity between surgical dogma and the evidence basis of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow, there is little data on hand surgeon practice patterns and trends in the management of this common clinical. The purpose of this study was to ascertain the current perspective of hand surgeons on the evaluation and management of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow. The secondary aim of the study was to assess the concordance of hand surgeons on definitions of the commonly used terms “subluxated” and “dislocated” for classification of ulnar nerve instability, and to assess the impact of these definitions on their operative decision making with respect to anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve.

In our study, the majority of surveyed surgeons indicated that they assess for ulnar nerve instability with physical examination, and 7.1% of respondents obtained dynamic ultrasound preoperatively. Calfee et al recently evaluated the interobserver reliability of clinical examination for instability by performing standardized examination on 400 elbows of 200 healthy volunteers with weighted kappa values of 0.70 and overall agreement of 84% between examiners. The results demonstrate significant but imperfect interobserver reliability; however, the authors note that ulnar nerve stability is difficult to assess in many patients, particularly those with elevated body mass index or a large medial head of the triceps. Dynamic ultrasound has been demonstrated to have a diagnostic accuracy of 89 to 100% when compared with the gold standard of intraoperative findings, and may provide additional useful preoperative data, including changes in nerve cross-sectional area, specific anatomic sites of nerve compression, perineural scarring, subcutaneous tissue thickness, medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve location, space-occupying lesions, and anatomic abnormalities such as anconeus epitrochlearis. 14 15 16 17

In this study, obtaining a preoperative ultrasound was a significant predictive factor for identifying respondents who make the decision to proceed with anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve in the preoperative time point. In our practice, we routinely obtain preoperative dynamic ulnar nerve ultrasound along with electrodiagnostic studies, as core components of the preoperative evaluation along with history and physical examination. It would be our contention that preoperative evidence of ulnar nerve subluxation or dislocation on ultrasound assists in decision making regarding ulnar nerve transposition, which facilitates preoperative patient counseling regarding incision length, immobilization type and length, and recovery time. Furthermore, preoperative ultrasound improves operative efficiency as the decision to anteriorly transpose is most commonly made preoperatively and directs intraoperative decision making regarding incision length, nerve stability, and transposition type.

In this study, the majority of surgeons performed in situ decompression for primary cubital tunnel syndrome with and without muscle weakness, 68.7 and 55.2%, respectively. This present trend for in situ decompression among surveyed hand surgeons is in line with evidence-based guidelines at present. Brauer and Graham demonstrated in a decision analysis model comparing in situ decompression, medial epicondylectomy, anterior subcutaneous transposition, and anterior submuscular transposition for operative management of cubital tunnel syndrome, that decompression alone was the preferred strategy to optimize outcomes. The authors, however, note that no well-designed randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing all four interventions exists in the literature. 18 Despite the limitations of the available evidence with few RCTs assessing outcomes of in situ decompression versus anterior transposition for cubital tunnel syndrome with associated ulnar nerve instability, the available meta-analyses do not clearly support anterior transposition for ulnar nerve subluxation or dislocation. 11 Bartels et al performed a prospective RCT of simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous transposition in 152 patients, of which 20 of 75 and 22 of 77 had ulnar nerve instability for the two treatments, respectively. 19 No significant difference was noted in outcomes or complications regardless of ulnar nerve instability at 1 year follow-up. These findings have been supported by RCTs by Biggs and Curtis and Gervasio et al demonstrating analogous results comparing in situ decompression and anterior transposition regardless of ulnar nerve stability. 20 21

We investigated whether the degree of perceived ulnar nerve “subluxation” or “dislocation” influenced a surgeon's decision making regarding the recommendation for anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve; 81.2% of surgeons identified ulnar nerve subluxation and 92.2% of surgeons, who identified ulnar nerve dislocation in simulated intraoperative photographs, would recommend anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve in the majority of the time to address the degree of perceived ulnar nerve instability. In this study, a preoperative decision time point to perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve was the only factor predictive of a surgeon's decision to perform an anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve ( p < 0.01), whereas history of ulnar nerve subluxation, muscle atrophy, subluxation on physical examination, electrodiagnostic testing, or ultrasound findings were not independent predictors for ulnar nerve transposition. Therefore, surgeons may variably utilize these factors to make the decision to transpose the ulnar nerve; however, those that decide to transpose the nerve preoperatively do not subsequently depart from this preoperative plan.

There is no consensus in the literature as to the appropriate way to define or classify ulnar nerve instability. In our practice, we utilize the definition of ulnar nerve instability akin to Okamoto et al in which the retrocondylar groove and the medial epicondyle tip serve as fixed landmarks to relate the position of the ulnar nerve. 7 “Stable” nerves are located within the retrocondylar groove in maximal flexion, whereas “unstable” nerves are termed “subluxated” if they rest anterior to the groove but posterior to the medial epicondyle tip with maximal elbow flexion. The nerve is considered to have “dislocated” if it lies anterior to the medial epicondyle tip with maximal elbow flexion. Analysis of the standardized photographs presented in the survey with these definitions would place image 1 as a “stable” nerve, images 2 to 5 as “unstable” nerves with 2 and 3 representing varying degrees of “subluxation” and 4 and 5 representing varying degrees of “dislocation.” Despite the lack of uniform definitions in the literature, analysis of the data from the surveyed surgeons correlates with this classification scheme ( Fig. 1 ). Image 1 (the “stable” nerve) was identified as not “subluxated” and not “dislocated” by 76.4 and 91.3% of respondents, respectively. Images 2 and 3 (the “unstable” and “subluxated” nerves) were identified as “subluxated” by 86.7 and 85.4% of respondents for images 2 and 3, respectively. Images 4 and 5 (the “unstable” and “dislocated” nerves) were identified as “dislocated” by 87.7 and 91.8% of respondents for images 4 and 5, respectively. We would therefore propose that this classification and definition be considered as a standardized method of communicating ulnar nerve instability. Interestingly, identification of ulnar nerves as “subluxated” or “dislocated” may not have as large an impact in practice patterns as “stable” or “unstable”; because with any degree of simulated ulnar nerve instability (images 2–5), the majority of respondents would perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve more than half of the time. Furthermore, increasing numbers of respondents would perform anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve for greater degrees of ulnar nerve “instability.”

We acknowledge the limitations in this study, which are common among questionnaire or survey-based research. The study was distributed to only members of the ASSH, and this poses a potential selection bias based on the membership of the ASSH. In addition, there are certainly many “nonhand” surgeons, shoulder and elbow surgeons, neurosurgeons, and general surgeons, who manage cubital tunnel syndrome. The survey was limited to hand surgeons as almost all hand surgeons perform or are at least knowledgeable regarding cubital tunnel syndrome management and other nonhand-related specialty societies were contacted and declined to participate. Our response rate was 27%; however, this is equivalent to or greater than other published surveys involving the ASSH membership. 22 23 Furthermore, our questionnaire classified ulnar entrapment severity based on the presence of muscle weakness; however, other factors may be taken into account in assessing disease severity, including symptom frequency and constancy and duration, sensibility, paresthesias, patient-reported outcomes measures, electrodiagnostic testing, and various classification schema including Gu's, Dellon's, and McGowan's, which were not reflected in the study design.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted the variability of the definitions for the degree of ulnar nerve instability at the elbow and further development of a classification system may be warranted to standardize treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wendlyn Daniels, Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic Survey Research Center, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street Southwest, Rochester, MN 55905, for assistance with the distribution of the survey; Dirk Larson, Department of Statistics, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street Southwest, Rochester, MN 55905, for support with statistical analysis; and Becca Daly, Meetings and Administrative Coordinator of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, for coordinating study approval and access to the distribution list.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Tang D T, Barbour J R, Davidge K M, Yee A, Mackinnon S E. Nerve entrapment: update. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(01):199e–215e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dy C J, Mackinnon S E. Ulnar neuropathy: evaluation and management. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9(02):178–184. doi: 10.1007/s12178-016-9327-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang D, Earp B E, Blazar P. Rates of complications and secondary surgeries after in situ cubital tunnel release compared with ulnar nerve transposition: a retrospective review. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(04):2940–2.94E7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calfee R P, Manske P R, Gelberman R H, Van Steyn M O, Steffen J, Goldfarb C A. Clinical assessment of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: reliability of instability testing and the association of hypermobility with clinical symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(17):2801–2808. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Childress H M. Recurrent ulnar-nerve dislocation at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38-A(05):978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard M J, Messmer C, Wray W H, Garrigues G E, Goldner R D, Ruch D S. Management of subluxating ulnar nerve at the elbow. Orthopedics. 2010;33(09):672. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto M, Abe M, Shirai H, Ueda N. Morphology and dynamics of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel. Observation by ultrasonography. J Hand Surg [Br] 2000;25(01):85–89. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Posner M A. Compressive neuropathies of the ulnar nerve at the elbow and wrist. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:305–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assmus H, Antoniadis G, Bischoff C et al. Cubital tunnel syndrome - a review and management guidelines. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2011;72(02):90–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozturk E, Sonmez G, Çolak A et al. Sonographic appearances of the normal ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(06):325–329. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caliandro P, La Torre G, Padua R . Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2016. Treatment for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow; p. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macadam S A, Gandhi R, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre K A. Simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous and submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(08):13140–1.314E15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matzon J L, Lutsky K F, Hoffler C E, Kim N, Maltenfort M, Beredjiklian P K. Risk factors for ulnar nerve instability resulting in transposition in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(02):180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babusiaux D, Laulan J, Bouilleau Let al. Contribution of static and dynamic ultrasound in cubital tunnel syndrome Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014100(4, Suppl):S209–S212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draghi F, Bortolotto C. Importance of the ultrasound in cubital tunnel syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2016;38(02):265–268. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruber H, Glodny B, Peer S. The validity of ultrasonographic assessment in cubital tunnel syndrome: the value of a cubital-to-humeral nerve area ratio (CHR) combined with morphologic features. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36(03):376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowalska B. Assessment of the utility of ultrasonography with high-frequency transducers in the diagnosis of postoperative neuropathies. J Ultrason. 2015;15(61):151–163. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2015.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brauer C A, Graham B. The surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: a decision analysis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007;32(06):654–662. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSE.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartels R H, Verhagen W I, van der Wilt G J, Meulstee J, van Rossum L G, Grotenhuis J A. Prospective randomized controlled study comparing simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous transposition for idiopathic neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: part 1. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(03):522–530. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000154131.01167.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggs M, Curtis J A. Randomized, prospective study comparing ulnar neurolysis in situ with submuscular transposition. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(02):296–304. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000194847.04143.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gervasio O, Gambardella G, Zaccone C, Branca D. Simple decompression versus anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve in severe cubital tunnel syndrome: a prospective randomized study. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(01):108–117. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000145854.38234.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yahya A, Malarkey A R, Eschbaugh R L, Bamberger H B. Trends in the surgical treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome: a survey of members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. Hand (NY) 2017:1.558944717725377E15. doi: 10.1177/1558944717725377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owusu A, Mayeda B, Isaacs J. Surgeon perspectives on alternative nerve repair techniques. Hand (NY) 2014;9(01):29–35. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.