Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a life-threatening disorder of the pulmonary circulation associated with loss and impaired regeneration of microvessels. Reduced pericyte coverage of pulmonary microvessels is a pathological feature of PAH and is partly due to the inability of pericytes to respond to signaling cues from neighboring pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs). We have shown that activation of the Wnt/PCP pathway is required for pericyte recruitment but whether production and release of specific Wnt ligands by PMVECs is responsible for Wnt/PCP activation in pericytes is unknown.

Methods:

Isolation of pericytes and PMVECs from healthy donor and PAH lungs was carried out using 3G5 or CD31 antibody conjugated magnetic beads. Wnt expression profile of PMVECs was documented via qPCR using a Wnt primer library. Exosome purification from PMVEC media was carried out using the ExoTIC device. Hemodynamic profile, right ventricular function and pulmonary vascular morphometry were obtained in a conditional endothelial specific Wnt5a knockout (Wnt5aECKO) mouse model under normoxia, chronic hypoxia and hypoxia recovery.

Results:

Quantification of Wnt ligand expression in healthy PMVECs co-cultured with pericytes demonstrated a 35-fold increase in Wnt5a, a known Wnt/PCP ligand. This Wnt5a spike was not seen in PAH PMVECs, which correlated with inability to recruit pericytes in matrigel co-culture assays. Exosomes purified from media demonstrated an increase in Wnt5a content when healthy PMVECs were co-cultured with pericytes, a finding that was not observed in exosomes of PAH PMVECs. Furthermore, the addition of either recombinant Wnt5a or purified healthy PMVEC exosomes increased pericyte recruitment to PAH PMVECs in co-culture studies. While no differences were noted in normoxia and chronic hypoxia, Wnt5aECKO mice demonstrated persistent pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular failure four weeks after recovery from chronic hypoxia, which correlated with significant reduction, muscularization and decreased pericyte coverage of microvessels.

Conclusions:

We identify Wnt5a as a key mediator for the establishment of pulmonary endothelial-pericyte interactions and its loss could contribute to PAH by reducing the viability of newly formed vessels. We speculate that therapies that mimic or restore Wnt5a production could help prevent loss of small vessels in PAH.

Keywords: Wnt5a, endothelial cells, pericytes, exosome, pulmonary arterial hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Pericytes are specialized perivascular cells embedded in the basement membrane of blood vessels where, in conjunction with neighboring endothelial cells, they support vessel maturation and stability1–3. In the lung, pericytes are mostly found associated with small pre-capillary arteries (<30μm), capillaries (~10μm) and post-capillary venules. It is thought that pericytes are responsible for regulation of vasomotor tone and structural support of microvessels4. When these vessels become muscularized, pulmonary vascular resistance increases resulting in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a life-threatening disorder associated with a progressive rise in pulmonary pressures resulting from 1) loss of small peripheral pulmonary arteries, 2) occlusion of larger proximal pulmonary arteries due to proliferation of smooth muscle cells and 3) deposition of extracellular matrix5. Efforts to elucidate the mechanisms related to small vessel loss in PAH have centered mostly on pulmonary endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, but not much was known about the contribution of pulmonary pericytes to PAH pathobiology until recently.

Work by our group and others have opened a window into the dynamic and complex role that pericytes play in the initiation and progression of vascular remodeling in PAH. For instance, a study by Ricard and colleagues reported increased pericyte numbers in close proximity to small and medium sized remodeled pulmonary microvessels in explanted PAH lungs. Interestingly, pericytes purified from PAH lungs display a pro-proliferative and pro-migratory phenotype in culture when exposed to endothelial-derived fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2)6. Chang and colleagues explored this further using a perlecan heparan sulfate (Hspg2) deficient mouse model, which demonstrated reduced pericyte recruitment to intra-acinar vessels in conjunction with reduced FGF2 production under hypoxia7. Given the role of pericytes in promoting the growth and maturation of microvessels, we predicted that failure of pericytes to associate with endothelial cells in PAH could contribute to small vessel loss by preventing proper vascular growth, structural stability and survival. Using several complementary approaches, we demonstrated that PAH pericytes fail to associate with healthy pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) in co-culture and decided to characterize the molecular mechanisms that drive pericyte recruitment to pulmonary microvessels. Transcriptome analysis of lung pericytes revealed upregulation in Fzd7 and cdc42, two genes involved in the Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway that is responsible for coordinating complex cell movements during tissue morphogenesis8. Our studies demonstrated that restoration of Wnt/PCP in PAH pericytes could partially restore recruitment to PMVECs and increase vessel stability. While these observations support an essential role for Wnt/PCP as a key regulator of endothelial-pericyte communication, how endothelial cells trigger Wnt/PCP activation to initiate pericyte recruitment and whether there is a disruption of Wnt ligand production in PAH PMVECs remains unknown.

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that Wnt5a production by PMVECs is an important step in initiating the migration of pericytes towards areas of new vessel growth and that stunted Wnt5a production by PAH PMVECs results in a lack of appropriate pericyte recruitment. We also show that PMVECs package Wnt5a in exosomes, which serve as vectors for transporting Wnt5a to neighboring pericytes. Most importantly, we show that Wnt5a enriched exosomes can be harvested from healthy PMVECs and used to partially restore pericyte recruitment in PAH PMVECs. Finally, we show that mice with Wnt5a KO restricted to endothelial cells demonstrate persistent pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure following recovery from hypoxia and that this correlates with reduced pericyte coverage of small (<50μm) vessels. Taken together, our study provides evidence that Wnt5a production by PMVECs is required for pericyte recruitment to small vessels and its loss contributes to vessel loss in PAH. We speculate that therapeutic strategies capable of restoring Wnt/PCP activity in the pulmonary circulation could help prevent loss and/or facilitate small vessel regeneration in PAH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An expanded Materials and Methods section containing detailed description of reagents, techniques and assays is provided in the online Data Supplement. The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article (and its online supplementary files). IRB approval was obtained, according to the guidelines noted in our institutions to Authors. All procedures performed in animals were in accordance with institutional guidelines. Clinical information can be found in Supplementary Table 1 and primer sequences used in the study can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical Analysis

The number of samples or animals studied per experiment are indicated in the figure legends. Values from multiple experiments are expressed as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s or Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests unless stated otherwise. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

PAH PMVECs Fail to Recruit Healthy Lung Pericytes in a Matrigel Co-culture Model.

Recruitment of pericytes by endothelial cells is a key step in angiogenesis, as it results in stabilization of newly formed vessels3. To test the capacity of healthy and PAH PMVECs to recruit pericytes, we co-cultured healthy human lung pericytes with either healthy donor or PAH PMVECs at a 5:1 ratio in matrigel, a biological matrix that promotes tubular-like structure formation by ECs in vitro9. Compared to PMVECs alone (Fig. 1A, upper panels), co-culture with healthy lung pericytes resulted in a significant increase in total tube length, total branching points and number of loops (Fig. 1B). In contrast, co-culture of healthy lung pericytes with PAH PMVECs under the same conditions resulted in a vascular network that was no different in size as that seen when PMVECs were cultured alone (Fig. 1A, bottom panels). To determine whether the observed differences in network size were due to alterations in pericyte distribution, we used cell membrane dyes to stain pericytes (PKH26, red) and PMVECs (PKH67, green) prior to seeding in matrigel co-culture. We found that healthy pericytes established contacts with endothelial cells mostly over the length of the vascular tubular structure (Fig. 1A, upper panel inset), whereas PAH pericytes tended to remain clustered within vascular nodes, resulting in thinner vascular tubular-like structures (Fig. 1A, bottom panel inset). Taken together, we found an apparent lack of migration and polarization of pericytes toward endothelial tubular-like structure generated by PAH PMVECs. This is interesting since this phenotype is reminiscent of the behavior seen when PAH pericytes are cultured with healthy PMVECs8.

Figure 1. PAH PMVECs fail to recruit healthy pulmonary pericytes (Pc).

(A) Matrigel assays of PMVEC from healthy donors (A, top) or from PAH patients alone (A, bottom) or in the presence of healthy donor Pc. Inset: IF of boxed areas. PMVEC are stained with PKH67 (green) and Pc with PKH26 (red). (B) Total tube length (left), total branching points (middle), and number of loops (right) with healthy donor or PAH PMVECs along or with pericytes from healthy subjects. (C) Boyden chamber comparing translocation of Pc in the presence of healthy donor or PAH PMVECs. After 6 hours, pericytes at the bottom of the inserts were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The mean number of pericytes from four random 20x fields was used for comparison. (D) Representative images of wound-healing co-culture assays in which PMVECs are on the left and pericytes on the right. Bottom row shows enlargements of the boxes in the top row. Cell polarity was assessed by pericentrin (red dots, indicates direction of cell movement), a marker of the microtubule organization center (MTOC). F-actin was stained in Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin and DAPI was in blue. Red arrowheads indicate cells pointing toward EC layer whereas white arrowheads indicate cells pointing the opposite direction. The white lines indicate 0 hours; dashed lines, 6 hours. Quantification of cell distance (bottom left) and percentage of polarized cells (bottom right) after 6 hours. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of three experiments. ∗P < 0.05 ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus PMVEC alone (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett post-test (B,C)) or versus control (unpaired t-test (D)). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Healthy Lung Pericytes Display Reduced Migration and Polarization Towards PAH PMVEC.

Extensive work has shown that recruitment of pericytes to developing vessels is the result of endothelial-released factors that direct pericyte polarization towards the vascular tubes1, 10. Since matrigel is a substrate that contains a multitude of cytokines that could confound analysis of chemotactic factors, we employed two complementary assays to narrow the contribution of endothelial-derived factors to pericyte recruitment. In the Boyden chamber assay, we seeded either healthy donor or PAH PMVECs on the bottom chambers of 24 well culture plates along with an inner chamber containing healthy lung pericytes seeded at top of an 8μm porous membrane. As anticipated, healthy pericytes spontaneously transmigrated in significantly greater numbers in the presence of healthy but not PAH PMVECs (Fig. 1C). To further link the PMVEC-induced mobilization of pericytes to cytoskeletal rearrangements required for their polarization, we co-cultured PMVECs and pericytes in a dual chamber slide that creates a gap between both cell groups akin to that of a wound-healing assay. Pericentrin, a protein located within the MTOC at the migrating front end, was used to measure the degree of cell polarization in pericytes. After six hours, close to 40% of healthy pericytes demonstrated polarization towards the healthy PMVEC monolayer and migrated ~200 microns from their starting point at 0 hours (Fig. 1D, left upper and lower panels). In contrast, healthy pericytes demonstrated only ~20% polarization and migrated significantly less in the presence of PAH PMVECs (Fig. 1D, right upper and lower panels).

Pericytes Induce Wnt5a Production in Healthy but not PAH PMVECs.

Previous work by our group identified the Wnt/PCP pathway as a major player in coordinating pericyte recruitment to PMVECs, since mutations in genes coding for Wnt/PCP receptors and signaling mediators in PAH pericytes blunted recruitment to healthy PMVECs8. Given that we observed a similar phenotype with co-cultures of PAH PMVECs and healthy lung pericytes, we sought to compare expression of well-characterized Wnt ligands in healthy vs. PAH PMVECs seeded alone and in co-culture. Both healthy and PAH PMVECs demonstrated upregulation in TGF beta and PDGF-BB gene expression, an expected finding given that these two molecules are known to coordinate establishment of endothelial-pericyte interactions during angiogenesis11. Compared to cells in monoculture, healthy PMVECs demonstrated a ~35-fold increase in Wnt5a expression, a response that was missing in PAH PMVECs under similar culture conditions (Fig. 2A). Likewise, western immunoblotting (WB) of lysates from healthy PMVECs showed a significant increase in Wnt5a expression in co-culture that was reduced in PAH PMVECs (Fig. 2B). It is worth pointing out that WB for the other Wnt ligands did not show consistent correlation with the mRNA expression parameters seen in qPCR (Supplement Fig. 1A). In addition, we tested different Wnt expression in the human whole lung lysate but did not see any significant differences in expression pattern (Supplement Fig. 1B).

Figure 2. Expression of Wnt5a fails to increase in PAH PMVECs co-cultured with healthy donor pericytes.

(A) SYBR Green qPCR analysis for Wnt/PCP-related components in PAH PMVEC or healthy donor co-culture with healthy Pc. The expression of each gene is shown relative to that in monoculture of healthy and PAH PMVECs. Data presented is the result of three independent studies. (B) Representative Western immunoblot (WB) images of Wnt5a in PAH PMVEC in mono or co-culture versus healthy donors. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus monoculture control (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post-test). OD, optical density. Densitometry was performed against a-tubulin. (C) IF of lung sections from human healthy donor and PAH patients stained for CD31 (green) and anti-human Wnt5a (red). (D) IF of human healthy vessel and PAH vascular lesions stained with 3G5 (red) for pericytes. CD31 is green and DAPI is blue. Graph indicates average number of 3G5 positive cells associated with microvessels by counting the ratio of number of 3G5+ cells overlapped with CD31+ cells in each group to the total number of CD31+ cells. White arrows indicate 3G5+CD31+ whereas white arrowheads indicate only 3G5+ staining. ∗∗P < 0.01 using the unpaired t-test. (E) Representative WB images of Wnt5a in isolated PMVECs from three donors versus three patients with PAH. Densitometry was performed against a-tubulin. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 using the unpaired t-test. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To confirm our cell culture findings, we sought to identify the expression pattern of Wnt5a in lung microvessels and PMVECs isolated from healthy donor and PAH lungs obtained at the time of transplant. Immunohistochemistry revealed a strong Wnt5a signal in the endothelium of healthy microvessels but not in PAH lesions (Supplement Fig. 2). Likewise, immunofluorescence of healthy donor lung sections revealed strong expression of Wnt5a in endothelium (Fig. 2C, left panel), which correlated with adequate pericyte coverage identified via 3G5, a pericyte marker (Fig. 2D, left panel, white arrows). However, in the endothelium found within PAH vascular lesions, Wnt5a expression was noticeably reduced (Fig. 2C, right panels) and, while pericytes were still observed in the vicinity, they were disassociated from endothelium resulting in reduced perivascular coverage (Fig. 2D, right panels). Since no significant differences in expression pattern of Wnt expression was found in the human whole lung lysates (Supplement Fig. 1B), we isolated PMVECs using magnetic beads and confirmed via WB a greater than 3-fold reduction in Wnt5a protein expression in PAH PMVECs from unrelated individuals compared to cells from healthy donors isolated under similar conditions (Fig. 2E). It is worth pointing out that Wnt5a expression was also reduced in the endothelium of medium sized (200–500μm) vessels (Supplement Fig. 3), which also exhibited a reduced number of pericytes near the intima (Supplement Fig. 4).

As part of our investigation, we also looked at the lungs of sugen/hypoxia rats11 for evidence of reduced Wnt5a endothelial expression in vascular lesions. Indeed, we found that Wnt5a expression was predominantly found in the endothelium of healthy vessels in wild type rats along with appropriate pericyte coverage (Supplement Fig. 5, upper panel). As predicted from our human studies, Wnt5a was mostly absent from endothelial cells in vascular lesions of sugen/hypoxia rats and correlated with dissociated pericytes (Supplement Fig. 5, lower panels).

Reduction of Wnt5a Production Results in Reduced Pericyte Recruitment to Healthy PMVECs.

As a member of the Wnt family of ligands, Wnt5a is a well-known activator of the Wnt/PCP pathway that helps coordinate cell polarization and complex movements during tissue morphogenesis and repair in response to injury12, 13. In a previous study, we demonstrated that stimulation of healthy pericytes with recombinant Wnt5a resulted in Wnt/PCP dependent pericyte motility, as evidenced by downstream RhoA/Rac1/cdc42 activity8 but whether endogenous production of Wnt5a by PMVECs could recapitulate these effects was not explored. To test whether loss of Wnt5a production in PAH PMVECs could account for their inability to appropriately recruit pericytes, we used siRNA transfection to knockdown Wnt5a in healthy PMVECs to levels comparable to those in PAH cells (Fig. 3A) and performed Boyden and modified wound healing assays. Similar to PAH PMVECs, pericytes demonstrated significantly reduced migration and polarization towards Wnt5a siRNA-treated (siWnt5a) PMVECs in both Boyden (Fig. 3B) and wound (Fig. 3C–3E) co-culture assays, which was rescued by adding recombinant Wnt5a. On the other hand, addition of a neutralizing Wnt5a antibody with siWnt5a further abrogated pericyte motility and polarity (Supplement Fig. 6).

Figure 3. Knockdown of Wnt5a in healthy donor PMVECs reduces pericyte recruitment but can be partially restored with recombinant Wnt5a (rWnt5a).

(A) WB for Wnt5a in total cell lysate from PMVEC transfected with either nontargeting (siCtrl) or Wnt5a-specific (siWnt5a) siRNAs. Densitometry was performed against a-tubulin. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus siCtrl using the unpaired t-test. (B) Boyden chamber assay comparing translocation of Pc in the presence of PMVECs with siCtrl or siWnt5a or rWnt5a. (C) Representative images of wound-healing co-culture assays. Enlargements of the boxes are shown in right panels. Cell polarity was assessed by pericentrin. The red lines indicate 0 hours; dashed lines, 6 hours. Quantification of distance migrated (D) and percentage of polarized cells (E) was performed after 6 hours. ∗P < 0.05 versus siCtrl using the unpaired t-test. (F) Matrigel assays of healthy PMVEC with siCtrl, siWnt5a or rWnt5a in the presence of healthy Pc. Images in the lower panel are tubular-like structures formed by PMVEC (PKH67, green) with or without the presence of pericytes (Pc) (PKH26, red). Total tube length (left), total branching points (middle), and number of loops (right) of PMVEC siCtrl, siWnt5a or rWnt5a with healthy pericytes from healthy subjects. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus siCtrl (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett post-test); # P< 0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test vs. siWnt5a +Pc). Scale bar = 100μm.

To further assess the impact of Wnt5a deficiency on angiogenesis, we seeded either non-targeting (siCtrl) or siWnt5a transfected healthy PMVECs on matrigel alone or in co-culture with healthy pericytes. In contrast to siCtrl transfected cells, the size of the vascular tubular-like network formed by siWnt5a PMVECs in single culture was significantly smaller as evidenced by reduced total tube length, branching points and number of loops (Fig. 3F, first two panels). As anticipated, siWnt5a PMVECs were unable to recruit healthy pericytes, as evidenced by the reduced number of pericytes associated with endothelial tubular-like structure and the smaller size of the tubular-like networks (Fig. 3F, fourth panel). Similar to its effect on Boyden and modified wound-healing assays, addition of recombinant Wnt5a to the siWnt5a PMVEC co-culture resulted in a significant increase in pericyte association and larger tubular-like networks (Fig. 3F, fifth panel). The same findings were recapitulated in a fibrin gel bead assay14, an angiogenesis assay that recapitulates early stages of sprouting angiogenesis using endothelial cells seeded in Cytodex3 microcarrier beads suspended in a fibrin gel matrix together with pericytes and covered with a fibroblast layer on the upper surface (Supplement Fig. 7).

Wnt5a Produced by PMVECs is Released to the Extracellular Space in Exosomes.

Originally thought to work in either autocrine and paracrine fashion, Wnts can also have long range effects, which is counterintuitive given that lipid-rich moieties limit their diffusion in the extracellular space15. This apparent paradox has recently been solved by the discovery that Wnts can be packaged into exosomes which are trafficked between cells and help maintain the biological activity of the ligand16, 17. Evidence that Wnt5a is being packaged into exosomes was observed when PMVECs were stained for Wnt5a when cultured alone or in the presence of pericytes seeded in Boyden chambers (Fig. 4A). Compared to the diffuse pattern seen in monoculture, Wnt5a in healthy PMVECs exposed to pericytes was organized into dense particles dispersed across the cytoplasm and heavily clustered in the membrane ruffles (Fig. 4A, upper two panels). In contrast, PAH PMVECs had a low grade of Wnt5a expression in monoculture that was expected given the documented low Wnt5a production in these cells; also, no demonstrable change in Wnt5a signal intensity or distribution was seen in co-culture (Fig. 4A, lower two panels). Based on these observations, we decided to isolate exosomes to compare the Wnt5a content and biological activity between healthy and PAH PMVECs.

Figure 4. Wnt5a is secreted in exosomes by PMVECs.

(A) IF for Wnt5a (green) in healthy donor or PAH PMVECs alone or co-cultured with pericytes in Boyden chambers. (B) TEM of one exosome (upper) and a CD63 immunogold labeled exosome (lower) isolated from co-culture. Scale bar=100nm. (C and D) WB for Wnt5a in total cell exosome lysate (CD81 as an internal control) from healthy donor (C) and PAH PMVEC (D) in mono and co-culture. ***P < 0.001 versus monoculture using the unpaired t-test. (E) Wound healing assay of PMVEC transfected with either nontargeting (siCtrl) or Wnt5a-specific (siWnt5a) siRNAs treated with exosomes isolated from healthy co-culture media. Cell polarity was assessed by pericentrin. F-actin was stained in Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin and DAPI was in blue. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus Ctrl (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post-test); ## P< 0.01, ### P<0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test vs. PAH PMVECs + Pc). Scale bar= 100um.

The most commonly used approach for exosome purification is ultracentrifugation but its major drawback is that it requires abundant source material. Our group has recently developed ExoTIC18, a novel technology to isolate exosomes from biological fluids using a nanoporous (30nm pore size), low protein binding filter membrane made from track-etched polycarbonate (Supplement Fig. 8A and B). Compared to ultracentrifugation and commercially available methods, the exosome yield with ExoTIC is 9 times greater despite a similar volume of starting material18. Nanosight quantification of exosomes in medium demonstrated a significantly larger number of exosomes in healthy cell co-culture vs. monoculture or siRNA treatments (See Supp. Video 1 and Supplement Fig. 8C-8D). While we saw a similar trend in PAH PMVECs co-culture, the exosome concentration was reduced (Data not shown). Using TEM, we documented the presence of an exosome isolated from the co-culture and other exosome immune-gold labeled for exosome markers CD63 (Fig. 4B). When compared to monoculture, there was greater Wnt5a protein content in exosomes as evidenced by WB (Fig. 4C) and IF staining (Supplement Fig. 9A); in contrast, we found no evidence of change in Wnt5a content upon co-culture in PAH exosomes (Fig. 4D).

Having quantified the Wnt5a content of exosomes, we next sought to test whether these exosomes have biological activity akin to that seen with recombinant Wnt5a in cell-based assays (see Fig. 3). Compared to serum free medium, incubation of healthy PMVEC-derived exosomes with siWnt5a PMVECs resulted in a significant increase in pericyte migration and polarization (Fig. 4E, top third panel). Likewise, addition of whole exosomes to modified wound healing co-cultures of PAH PMVECs also resulted in a significant increase in pericyte migration and polarization to the endothelial monolayer (Fig. 4E, lower right panels). To determine whether the salutary effect of healthy exosomes is dependent on Wnt5a content, we repeated the study using exosomes isolated from siWnt5a PMVECs. Compared to PAH PMVECs treated with siCtrl exosomes, PAH cells treated with siWnt5a exosomes showed a significantly reduction in pericyte migration while no difference in polarity was observed in either group (Supplement Fig. 9B). To further confirm the existence and effect of exosomes, we treated co-culture with non-fractionated whole media from siWnt5a treated ECs. We found less pericyte motility and polarization when compared to non-fractionated media of siCtrl treated cells (Supplement Fig. 10).

Mice with Endothelial Specific Wnt5a Deletion Have Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Ventricular Dilatation After Recovery from Hypoxia.

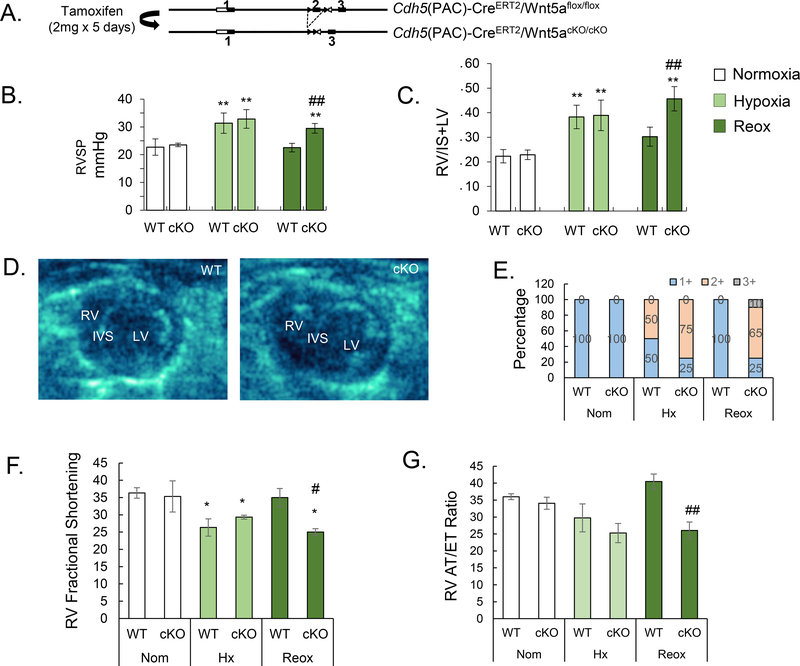

In an effort to assess the biological contribution of Wnt5a in vivo, we sought to identify a viable mouse model of Wnt5a knockout (KO). Global Wnt5a KO (MGI: 1857617) is embryonically lethal as a result of multiple defects incompatible with life, including lung hypoplasia and congenital cardiac anomalies19 (Supplement Fig. 11A). To bypass this, we generated a conditional endothelial specific Wnt5a KO mouse line (Wnt5aECKO), in which exon 2 of the Wnt5a gene is flanked by two loxP sites (Fig. 5A). One week after tamoxifen treatment, Wnt5a expression was substantially reduced in endothelial cells as evidenced by both WB of purified murine PMVECs and lung IF (Supplement Fig. 11B and 11C). We compared the hemodynamic profile of wild type (WT) and Wnt5aECKO mice under normoxia, hypoxia (3 weeks of FiO2 10%) and hypoxia recovery (1 month under normoxia). While there were no significant differences in right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) between the groups, Wnt5aECKO demonstrated persistently elevated RVSP after one month in recovery (Fig. 5B). We found that Wnt5aECKO mice in the recovery group also demonstrated persistent right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy, as indicated by a significantly higher Fulton index compared to WT mice (Fig. 5C). To further assess RV structure and function, echocardiography was performed in WT and Wnt5aECKO mice across all 3 experimental conditions. Again, we found no difference between WT and Wnt5aECKO mice until the recovery arm was assessed. Compared to WT, Wnt5aECKO mice in recovery demonstrated RV enlargement (Fig. 5D and E, See Supplement Video 2 and 3) and decreased RV function as evidenced by lower RV Fractional Shortening (RVFS, Fig. 5F) and RV acceleration time over ejection time (RV AT/ET, Fig. 5G). Finally, we found no evidence of abnormal heart rate, left ventricular size or function across genotypes or experimental conditions (Data not shown).

Figure 5. Persistent elevation of right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) and RV failure in Wnt5aECKO mice after recovery from hypoxia (Reox).

(A) Diagram showing the strategy for generation of Wnt5aECKO mice. (B) RVSP and (C) Fulton Index of wild type (WT) and Wnt5aECKO (cKO) in normoxia, hypoxia and recovery (Reox). (D) Echo images of WT and Wnt5aECKO in recovery. right (RV) and left ventricles (LV), interventricular septum (IVS). (E) The percentage of RV enlargement in echo images was scored as follows: 1+ normal (RV is invisible), 2+ some degree impaired (visible), 3+ RV hypertrophy (obvious enlargement). RV Fractional Shortening (F) and RV acceleration time over ejection time (G) in normoxia, hypoxia and recovery (reox). Data are expressed as means ± SEM of at least six random images. N=11 for each group. ∗ P<0.05, ∗∗P<0.01 (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post-test). # P< 0.05, ##P<0.01, (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test vs. WT Reox).

Wnt5aECKO Mice Demonstrate Persistent Loss and Muscularization of Microvessels in Hypoxia Recovery.

Given evidence of persistent elevation of RVSP and RV failure in Wnt5aECKO mice in hypoxia recovery, we speculated that these mice would also demonstrate abnormalities in pulmonary microvascular structure linked to increased vascular resistance and greater cardiac afterload. To test this, we carried out morphometric studies in lung tissue sections from WT and Wnt5aECKO mice under all 3 conditions and compared both number and extent of muscularization of microvessels (<100μm).

By counting number of microvessels per 100 alveoli, we found a similar drop in vessel numbers in both groups under hypoxia, which returned to normoxia levels in WT mice after hypoxia recovery but remained persistently reduced in Wnt5aECKO mice (Fig. 6A). The same trend was found when the percentage of muscularized vessels was documented. In hypoxia, between 40–50% of all vessels were muscularized in both groups; however, upon return to normoxia, WT mice demonstrated a significant reduction in muscularized vessels (~25%) whereas no change was noted in Wnt5aECKO mice (Fig. 6B). Further assessment using microCT demonstrated a significant reduction in tertiary blood vessel length and number of distal vessels in Wnt5aECKO mice after recovery (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Wnt5aECKO mice have persistent loss and muscularization of microvessels in recovery.

(A) Quantification of number of vessels per 100 alveoli and (B) number of muscularized in microvessels (diameter < 50um). Data are expressed as means ± SEM of at least six random images; each group has 11 different mice. (C) MicroCt imaging and enlarged images of distal vessels from Reox WT and cKO mice. Quantification of tertiary blood vessel length (um) and number of distal vessels on the right. (D) IF of OCT embedded lung sections from Reox WT (upper) and cKO (lower) mice. Smooth muscle layer was stained with a-SMA (red), pericytes were stained with NG2 (magenta) and endothelium was stained with CD31 (green). Scale bar =25um (E) Quantification of NG2 positive cell pericyte coverage in vessels from WT and cKO mice in recovery group. (F) IF of OCT embedded lung sections from Reox WT and cKO mice which stained for CD31 (green), 3G5(red) and cPARP. White arrow indicates 3G5 overlap with cPARP. ∗∗P < 0.01, unpaired t-test. ∗∗∗P<0.001 (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post-test); ##P<0.01, (one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test vs. WT Reox). Scale bar =10um.

As previously shown by Ricard et al and by the studies included here, pericytes found adjacent to PAH vascular lesions appear detached from the endothelial surface, where they would otherwise be found embedded within the basement membrane6. Since inappropriate pericyte coverage of vessels can be associated with small vessel loss through endothelial dysregulation and apoptosis, we stained lung tissue sections from WT and Wnt5aECKO mice in the hypoxia recovery group with NG2, a marker for pericytes20, 21. We found that pericytes in WT mice were found in the immediate perivascular space of microvessels (Fig. 6D, upper panels). However, as with PAH lungs, pericytes were found dissociated from microvessels and relocated to the surrounding lung parenchyma (Fig. 6D, lower panels) resulting in reduced vessel coverage (Fig. 6E). We performed confocal imaging of vibratome lung sections (200–300 μm) to perform 3-D reconstruction of microvessels. Indeed, we found the number of NG2+ pericytes was reduced in endothelium of Wnt5aECKO recovery mice (Supplement Fig. 12, video 4 for control and video 5 for Wnt5aECKO recovery). In addition, the dissociation of pericytes from ECs resulted in increased EC apoptosis as evidenced via cPARP staining (Figure 6F). No differences were found in normoxia and hypoxia lungs (Supplement Figure 13).

DISCUSSION

Pericytes are key players in the growth and stability of blood vessels and their behavior has been the focus of many studies interested in identifying novel therapeutic approaches to treat common vascular disorders (e.g. diabetic retinopathy22, 23) as well as in cancer, where aberrant angiogenesis is a major feature of many tumors24–26. The contribution of pericytes to the preservation and proper maintenance of the pulmonary microcirculation has recently become the subject of studies centered on elucidating the link between pericytes and development of vascular remodeling in PAH. The study by Ricard and colleagues was the first in pointing out that pericytes appear in a large number around remodeled vessels while they exhibit a pro-proliferative and pro-migratory phenotype in vitro reminiscent of PAH pulmonary smooth muscle cells6. Indeed, we have found that PAH pericytes exhibit a remarkable pro-proliferative capacity that translates into smooth muscle cell (SMC)-like properties such as increased contractility and metabolic alterations in mitochondrial oxidation27. However, the perivascular location of PAH pericytes documented by Ricard et al was assessed to be distant from the intima6; this is remarkable given that the definition of a pericyte is its close association with endothelial cells, with whom they share direct contacts and the basement membrane3. This led us to speculate that, in addition to abnormal proliferation and a phenotypic switch, there may be an inherent disorder in cell-cell communication that prevents pericytes from establishing functional connections with endothelial cells.

Our group has shown that PAH pericytes have reduced capacity to associate with PMVECs through a defect in Wnt/PCP activity, which can be partially restored by increasing the expression of specific pathway components8. These studies revealed that, in contrast to healthy cells, co-culture of PAH pericytes with healthy PMVECs led to formation of smaller tube-like networks with markedly reduced pericyte coverage. The reason for reduced pericyte coverage was found to be an inability for PAH pericytes to polarize and migrate towards PMVECs as shown by wound co-culture assays. The Wnt/PCP pathway is a conserved developmental pathway responsible for coordinating cell organization during tissue morphogenesis. Mutations that reduce Wnt/PCP activity are associated with various clinical musculoskeletal dysplastic syndromes28–30; however, impact on development and repair responses in the cardiopulmonary system have yet to be fully characterized8. In the present study, we provide evidence that highlights the importance of Wnt5a to the establishment of endothelial-pericyte interactions during repair of the pulmonary circulation. We propose that, in the setting of vascular injury, PMVECs must produce Wnt5a to trigger Wnt/PCP in pericytes to attract them to associate with blood vessels, thereby preserving the number of functional vessels within the microcirculation (See model, Fig. 7). In this paper, we have selectively used only healthy pericytes in our studies, but we must stress that studies conducted by co-culturing PMVECs and PAH pericytes fail to produce any tube-like networks in matrigel co-culture studies (Data not shown). We believe this to be evidence that there is synergism in how PMVEC and pericytes interact and that the presence of defects in both cells types is additive, resulting in catastrophic consequences for vessel regeneration.

Figure 7. Proposed model.

In the setting of vascular injury, PMVECs produce Wnt5a packaged in exosomes to recruit pericytes to associate with blood vessels, thereby preserving the number of functional vessels within the microcirculation (A). A lack of Wnt5a production significantly impair establishment of endothelial-pericyte interactions thus resulting in loss of small vessels leading to PAH (B). MVE=microvesicles.

Establishment of endothelial-pericyte communication is the result of an elegant and dynamic exchange of cytokines by both cell types during the final steps of angiogenesis. Production of PDGF-BB by endothelial cells is responsible for triggering pericyte motility via its interaction with the PDGF receptor31; likewise, TGF beta production by pericytes is responsible for inducing endothelial quiescence as part of vessel maturation32. Additionally, a mutual regulatory relationship between Wnt5a and the matricellular protein CCN1 also coordinates the EC and pericyte interaction during anigiogenesis.33 In our present studies, we find that production of Wnt5a by PMVECs appears to be increased upon co-culture with pericytes suggesting that a pericyte-derived factor may be responsible for increasing Wnt5a gene expression in endothelial cells. A major question that remains is: how is Wnt5a production regulated in PMVECs and why is this suppressed in PAH? A possible explanation comes from DNA sequencing studies that show that the Wnt5a promoter is a nexus for transcription factors that area downstream of multiple signaling pathways involved in the regulation of developmental processes and response to injury. Based on the analysis, the Wnt5a promoter has putative binding sites for many signaling pathways such as MAP kinase, BMP, TGF beta and EGF, among others34. This is of great relevance as evidence of dysregulation of many of these same pathways have been documented in PAH studies35. Another aspect to be considered is that the transcriptional activity of some of these pathways could also be impacted by the state of methylation and histone repression of the Wnt5a promoter, a finding that has been documented in cancer studies36. Our group is currently engaged in studies to dissect the contribution of epigenetics and signaling crosstalk at the level of the Wnt5a promoter as this strategy could open tantalizing possibilities for augmenting Wnt5a production in PAH.

Wnts have been considered to be autocrine and paracrine factors with limited range. Recently, it has been shown that Wnts can be secreted to the extracellular environment into exosomes, microparticles measuring 50–100nm in size responsible for the transport of proteins, RNA and DNA between cells37. In cancer, exosomes containing Wnt11 are released by fibroblasts to activate Wnt/PCP and drive breast cancer proliferation and invasiveness16. Importantly, exosomes extracted from the blood of monocrotaline treated mice can cause PAH when administered into healthy mice38 whereas the opposite effect is seen when exosomes from healthy animals are injected in MCT treated subjects39. Based on this, we speculated that PMVECs release Wnt5a in exosomes to attract pericytes to pulmonary blood vessels. We acknowledge that the presence of other factors besides Wnt5a is required for attracting pericytes to endothelial cells. Signaling peptides associated with exosomes can be found inside and/or attached to the outer membrane. We attempted immunogold labeling to identify the location of Wnt5a in exosomes but did not see a signal via TEM. While it is unlikely that Wnt5a is located in the exosome exterior, it does not rule out that Wnt5a could be located in the lumen where antibody permeability is reduced. Beyond the studies presented here, we believe that it is important to perform comprehensive genetic and proteomic characterization of the exosome content of healthy and PAH PMVECs, looking at the full range of Wnt related genes and other markers of signaling activity. This will allow us to identify major candidate pathways that could crosstalk with Wnt signaling to regulate endothelial-pericyte interactions in the pulmonary circulation.

The chronic hypoxia mouse model is a well-established model of experimental pulmonary hypertension that has been used extensively to characterize the contribution of individual genes to PAH pathogenesis40. While it is true that the model does not capture the full spectrum of vascular pathology seen in PAH, lungs explanted from mice exposed to chronic hypoxia demonstrate a significant reduction in the number of alveolar microvessels that correlates with moderate muscularization of precapillary arteries and elevation in pulmonary pressures41, 42. It is important to reiterate that pericyte recruitment and establishment of endothelial-pericyte contacts is a highly dynamic process that takes place over a critical time period of angiogenesis. One limitation of our animal studies is that we measured vessel number and pericyte coverage only at the end of the experimental period (21 days of hypoxia and recovery) and not at earlier time points, when active angiogenesis and pericyte recruitment are likely taking place. Also, we cannot rule out that some pericytes may respond to hypoxia by differentiating into smooth muscle like cells and thereby contribute to muscularization. This possibility has been proposed by several studies and could explain the persistence of muscularization seen in Wnt5aECKO mice after recovery from hypoxia43. It is worth pointing out that loss of Wnt5a also reduced the angiogenic properties of PMVECs as evidenced in our siRNA-based studies and supported by several studies focused on other vascular beds44, 45. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that Wnt5a may be required not only to recruit pericytes but also to ensure early assembly of blood vessels, a critical step that precedes pericyte recruitment, a major step towards regenerating vessels lost to hypoxia. Finally, it must be pointed out that we observed a greater number of pericytes and Wnt5a expression in murine lungs compared to rat or human lung samples. This could very well represent a trait unique to this species and could potentially hint at a greater reparative potential of the mouse lung compared to other species. Ongoing studies looking at progenitor cells in the lung are likely to expand on the role of Wnt5a and Wnt/PCP in this setting.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to uncover a key role for Wnt5a in establishing PMVEC and pericyte interaction in distal vessels iterating that its loss could contribute to progressive vessel remodeling in PAH. As a modifier of BMP signaling in endothelial and smooth muscle cells46, 47, Wnt/PCP signaling is a strong candidate to understand how pulmonary angiogenesis is orchestrated. Understanding how Wnt5a and other Wnt/PCP components participate in pulmonary angiogenesis will provide a new paradigm to understand how pulmonary vessels can regenerate following injury, providing new avenues for therapeutic interventions aimed at reversing progression of PAH. Beyond this, it is plausible that Wnt/PCP could play similar role in other diseases where abnormal endothelial-pericyte interactions occur and therapeutic interventions may serve to alter the natural disease course.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

-

1

What is new? (no more than 100 words, formatted as 2–3 bullets)

Pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) isolated from PAH patients and endothelium from PAH tissue have reduced expression of Wnt5a.

Healthy PMVECs produce and package Wnt5a in forms of exosomes which regulate pericyte recruitment, motility and polarity.

Chronic hypoxic Mice lacking Wnt5a in endothelium demonstrate persistent pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure and reduced pericyte coverage after reoxygenation.

-

2

What are the clinical implications? (no more than 100 words, formatted as 2–3 bullets).

Uncover a key role for Wnt5a in establishing PMVEC and pericyte interaction in distal vessels iterating that its loss could contribute to progressive vessel remodeling in PAH.

Provide a new mechanism that Wnt5a is produced in exosomes in PMVECs.

Address promising therapeutic strategies towards the restoration of Wnt/PCP pathway in endothelial-pericyte communication which will help prevent microvessel loss in PAH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Drs. Marlene Rabinovitch and Christophe Guignabert for their critical review of this work. Lung tissues from PAH and control patients were provided by the Pulmonary Hypertension Breakthrough Initiative, which is funded by the NIH and managed at Stanford by Drs. Marlene Rabinovitch and Roham T. Zamanian. The tissues were procured at the Transplant Procurement Centers at Stanford University, Cleveland Clinic, and Allegheny General Hospital and de-identified patient data were obtained via the Data Coordinating Center at the University of Michigan. The authors thank all patients and their proxies who participated in this study. The authors are also grateful to Mrs. Patricia Angeles del Rosario and Mr. Matthew Bill for helping with the collection and processing of blood samples and Mr. Andrew Hsi for helping organize the patient database.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by an NIH R01 HL134776, R01 HL134776–02, R03 HL133423–01, American Heart Association Beginning Grant in Aid, a Stanford Cardiovascular Institute (CVI) and Translational Research and Applied Medicine (TRAM) to V. de Jesus Perez. K. Yuan was supported by American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (15SDG25710448), the Parker B. Francis Fellowship, and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association Proof of Concept Award.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ribatti D, Nico B and Crivellato E. The role of pericytes in angiogenesis. Int J Dev Bio. 2011;55:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamagishi S and Imaizumi T. Pericyte biology and diseases. Int J Tissue React 2005;27:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz-Flores L, Gutierrez R, Madrid JF, Varela H, Valladares F, Acosta E, Martin-Vasallo P and Diaz-Flores L Jr. Pericytes. Morphofunction, interactions and pathology in a quiescent and activated mesenchymal cell niche. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:909–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapanci Y, Ribaux C, Chaponnier C and Gabbiani G. Cytoskeletal features of alveolar myofibroblasts and pericytes in normal human and rat lung. J Histochem Cytochem. 1992;40:1955–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Kutryk MJ, Kuliszewski MA, Karoubi G, Courtman DW, Zucco L, Granton J and Stewart DJ. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor-2 signaling promotes pulmonary arterial endothelial cell survival: implications for loss-of-function mutations in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2006;98:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricard N, Tu L, Le Hiress M, Huertas A, Phan C, Thuillet R, Sattler C, Fadel E, Seferian A, Montani D, Dorfmuller P, Humbert M and Guignabert C. Increased pericyte coverage mediated by endothelial-derived fibroblast growth factor-2 and interleukin-6 is a source of smooth muscle-like cells in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2014;129:1586–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YT, Tseng CN, Tannenberg P, Eriksson L, Yuan K, de Jesus Perez VA, Lundberg J, Lengquist M, Botusan IR, Catrina SB, Tran PK, Hedin U and Tran-Lundmark K. Perlecan heparan sulfate deficiency impairs pulmonary vascular development and attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan K, Orcholski ME, Panaroni C, Shuffle EM, Huang NF, Jiang X, Tian W, Vladar EK, Wang L, Nicolls MR, Wu JY and de Jesus Perez VA. Activation of the Wnt/planar cell polarity pathway is required for pericyte recruitment during pulmonary angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnaoutova I, George J, Kleinman HK and Benton G. The endothelial cell tube formation assay on basement membrane turns 20: state of the science and the art. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armulik A, Genove G and Betsholtz C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21:193–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe K, Toba M, Alzoubi A, Ito M, Fagan KA, Cool CD, Voelkel NF, McMurtry IF and Oka M. Formation of plexiform lesions in experimental severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2010;121:2747–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuchi A, Yamamoto H, Sato A and Matsumoto S. Wnt5a: its signalling, functions and implication in diseases. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2012;204:17–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishita M, Enomoto M, Yamagata K and Minami Y. Cell/tissue-tropic functions of Wnt5a signaling in normal and cancer cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:346–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakatsu MN, Davis J and Hughes CC. Optimized fibrin gel bead assay for the study of angiogenesis. J Vis Exp. 2007;3:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross JC and Boutros M. Secretion and extracellular space travel of Wnt proteins. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luga V, Zhang L, Viloria-Petit AM, Ogunjimi AA, Inanlou MR, Chiu E, Buchanan M, Hosein AN, Basik M and Wrana JL. Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell. 2012;151:1542–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L and Wrana JL. The emerging role of exosomes in Wnt secretion and transport. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;27:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang LG, Kong MQ, Zhou S, Sheng YF, Wang P, Yu T, Inci F, Kuo WP, Li LJ, Demirci U and Wang S. An integrated double-filtration microfluidic device for isolation, enrichment and quantification of urinary extracellular vesicles for detection of bladder cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi TP, Bradley A, McMahon AP and Jones S. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development. 1999;126:1211–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karram K, Chatterjee N and Trotter J. NG2-expressing cells in the nervous system: role of the proteoglycan in migration and glial-neuron interaction. J Anat. 2005;207:735–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stallcup WB, You WK, Kucharova K, Cejudo-Martin P and Yotsumoto F. NG2 Proteoglycan-Dependent Contributions of Pericytes and Macrophages to Brain Tumor Vascularization and Progression. Microcirculation. 2016;23:122–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammes HP, Lin J, Renner O, Shani M, Lundqvist A, Betsholtz C, Brownlee M and Deutsch U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2002;51:3107–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W, Yanoff M, Liu X and Ye X. Retinal capillary pericyte apoptosis in early human diabetic retinopathy. Chin Med J (Engl). 1997;110:659–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu C, Shahzad MM, Moreno-Smith M, Lin YG, Jennings NB, Allen JK, Landen CN, Mangala LS, Armaiz-Pena GN, Schmandt R, Nick AM, Stone RL, Jaffe RB, Coleman RL and Sood AK. Targeting pericytes with a PDGF-B aptamer in human ovarian carcinoma models. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:176–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motegi S, Leitner WW, Lu M, Tada Y, Sardy M, Wu C, Chavakis T and Udey MC. Pericyte-derived MFG-E8 regulates pathologic angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2024–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato Y Persistent vascular normalization as an alternative goal of anti-angiogenic cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1253–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan K, Shao NY, Hennigs JK, Discipulo M, Orcholski ME, Shamskhou E, Richter A, Hu X, Wu JC and de Jesus Perez VA. Increased Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 4 Expression in Lung Pericytes Is Associated with Reduced Endothelial-Pericyte Interactions and Small Vessel Loss in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:2500–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bacino C ROR2-Related Robinow Syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, Bird TD, Fong CT, Mefford HC, Smith RJH and Stephens K, eds. GeneReviews ® [Internet]Seattle (WA); 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarzer W, Witte F, Rajab A, Mundlos S and Stricker S. A gradient of ROR2 protein stability and membrane localization confers brachydactyly type B or Robinow syndrome phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4013–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nusse R Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 2005;15:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A and Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047–3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antonelli-Orlidge A, Saunders KB, Smith SR and D’Amore PA. An activated form of transforming growth factor beta is produced by cocultures of endothelial cells and pericytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4544–4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, Elaskandrany M, Lau LF, Lazzaro D, Grant MB and Chaqour B. Interplay between CCN1 and Wnt5a in endothelial cells and pericytes determines the angiogenic outcome in a model of ischemic retinopathy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katoh M and Katoh M. Transcriptional mechanisms of WNT5A based on NF-kappaB, Hedgehog, TGFbeta, and Notch signaling cascades. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranchoux B, Harvey LD, Ayon RJ, Babicheva A, Bonnet S, Chan SY, Yuan JX and Perez VJ. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension: an evolving landscape (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm Circ. 2018;8: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaidya H, Rumph C and Katula KS. Inactivation of the WNT5A Alternative Promoter B Is Associated with DNA Methylation and Histone Modification in Osteosarcoma Cell Lines U2OS and SaOS-2. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro MF, Zhu H, Millard RW and Fan GC. Exosomes Function in Pro- and Anti-Angiogenesis. Curr Angiogenes. 2013;2:54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aliotta JM, Pereira M, Amaral A, Sorokina A, Igbinoba Z, Hasslinger A, El-Bizri R, Rounds SI, Quesenberry PJ and Klinger JR. Induction of pulmonary hypertensive changes by extracellular vesicles from monocrotaline-treated mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:354–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aliotta JM, Pereira M, Wen S, Dooner MS, Del Tatto M, Papa E, Goldberg LR, Baird GL, Ventetuolo CE, Quesenberry PJ and Klinger JR. Exosomes induce and reverse monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110:319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan JJ, Marsboom G and Archer SL. Rodent models of group 1 pulmonary hypertension. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;218:105–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guignabert C, Alvira CM, Alastalo TP, Sawada H, Hansmann G, Zhao M, Wang L, El-Bizri N and Rabinovitch M. Tie2-mediated loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in mice causes PDGF receptor-beta-dependent pulmonary arterial muscularization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1082–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Jesus Perez VA, Yuan K, Orcholski ME, Sawada H, Zhao M, Li CG, Tojais NF, Nickel N, Rajagopalan V, Spiekerkoetter E, Wang L, Dutta R, Bernstein D and Rabinovitch M. Loss of adenomatous poliposis coli-alpha3 integrin interaction promotes endothelial apoptosis in mice and humans. Circ Res. 2012;111:1551–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volz KS, Jacobs AH, Chen HI, Poduri A, McKay AS, Riordan DP, Kofler N, Kitajewski J, Weissman I and Red-Horse K. Pericytes are progenitors for coronary artery smooth muscle. Elife. 2015;4:e10036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arderiu G, Espinosa S, Pena E, Aledo R and Badimon L. Monocyte-secreted Wnt5a interacts with FZD5 in microvascular endothelial cells and induces angiogenesis through tissue factor signaling. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014;6:380–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi YN, Zhu N, Liu C, Wu HT, Gui Y, Liao DF and Qin L. Wnt5a and its signaling pathway in angiogenesis. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;471:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, Wu JC, Axelrod JD, Cooke JP, Amieva M and Rabinovitch M. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 induces pulmonary angiogenesis via Wnt-beta-catenin and Wnt-RhoA-Rac1 pathways. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:83–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez VA, Ali Z, Alastalo TP, Ikeno F, Sawada H, Lai YJ, Kleisli T, Spiekerkoetter E, Qu X, Rubinos LH, Ashley E, Amieva M, Dedhar S and Rabinovitch M. BMP promotes motility and represses growth of smooth muscle cells by activation of tandem Wnt pathways. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:171–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.