Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which modifies reimbursement for office evaluation and management (E&M) visits. This policy moves payment to a single rate for levels 2 through 4 office E&M visits, regardless of complexity.

Methods:

Using a 20% sample of 2015 national Medicare claims, we identified urology practices and their practice organization, academic affiliation, and degree of office focus (i.e. proportion of revenues from office visits). Using billing data for each practice, we calculated the revenues expected under the current system and the new policy (both E&M payments and a new add-on code). For each practice, we determined the impact of new payment rates on total Medicare payments.

Results:

We identified 2,822 practices: 1,372 (48.6%) solo practices, 1,033 (36.6%) multispecialty groups, 322 (11.4%) small urology groups, and 95 (3.4%) large urology groups. Under the new reimbursement rates, the median practice would have a 0.9% increase in Medicare Part B payments (range −20.4% to +50.3%) and, with the add-on code, an increase of 6.8% (range −7.5% to +74.9%). Solo practices had the most heterogeneity, with a quarter losing at least 2.3%. The median multispecialty group would increase payments by 0.4% (range −13.7% to 50.3%). However, the 107 (10.4%) academic multispecialty groups had a median gain of only 0.1% (range −2.8% to +8.1%).

Conclusions:

Urology groups would, on average, benefit from the anticipated change in Medicare office E&M visit payments. However, solo practices with a high office focus and academic multispecialty practices may see reduced Medicare payments.

Keywords: Medical fees, office visit, Medicare

Introduction

Office evaluation and management (E&M) visits are the most common physician services and accounted for approximately $23 billion in Medicare spending in 2017.1 Payment for these services is directed by the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which currently divides office visits into 5 levels with increasing fees commensurate with the increasing complexity of providing the service (Table 1). Since the adoption of documentation guidelines in the mid-1990s, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has required specific documentation to justify the visit level billed.2,3 These guidelines were immediately unpopular among physicians, who criticized government intrusion into medical decision-making, the time-consuming paperwork, and complexity of the administrative burden implied by the change.4

Table 1.

Current and anticipated standardized payment rates for office E&M visits.

| Visit level | CPT code | 2018 payment ($) | 2021 payment ($) | 2021 payment with add-on code ($) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New patient visits | 1 | 99201 | 45 | 44 | 44 |

| 2 | 99202 | 76 | 130 | 143 | |

| 3 | 99203 | 110 | 130 | 143 | |

| 4 | 99204 | 167 | 130 | 143 | |

| 5 | 99205 | 211 | 212 | 212 | |

| Established patient visits | 1 | 99211 | 22 | 24 | 24 |

| 2 | 99212 | 45 | 90 | 103 | |

| 3 | 99213 | 74 | 90 | 103 | |

| 4 | 99214 | 109 | 90 | 103 | |

| 5 | 99215 | 148 | 149 | 149 |

As part of its effort to put “patients over paperwork”, CMS announced revisions to the leveling policy in November 2018. The revised payment policy, effective January 2021, reduces documentation requirements and merges payments for levels 2 through 4 to a single weighted average rate. CMS has argued that this payment reform would reduce administrative burden on both the provider and payer, eliminate distinctions between visit levels that were largely outdated, and decrease the potential for fraud.5 Responding to concerns from physicians, policymakers also maintained that there would be minimal effect on payments to any given specialty. While the policy change intended to hold payment relatively neutral within a specialty, the possibility of disproportionate gains and/or losses looms large as patient complexity and leveling patterns likely vary considerably across different practice contexts. For instance, referral-based practices, such as those in academic medical centers, plausibly see a more complex patient population than a small community practice.

For these reasons, we performed a study to understand the effects of payment policy reform on urology practices. Specifically, we used national Medicare data to characterize the consequences across a variety of meaningful practice contexts to help stakeholders anticipate and plan for the upcoming change.

Methods

Study Population

Using a 20% national sample of Part B Medicare claims from 2015, we identified all office E&M visits (Current Procedural Terminology codes 99201 through 99205 [new patient visits] and 99211 through 99215 [established patient visits]). This captured all leveling codes that are included in the policy change that takes effect January 1, 2021.5 We then identified the provider associated with all qualifying E&M payments using their National Provider Identifier number and characterized their specialty using explicit codes within the claims. We assigned each urologist to their practice context using the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty file from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. For this study, we included all group practices that included at least one urologist (n = 2,981 group practices). Of these, we excluded those in the bottom 5th percentile for total Medicare Part B payments in 2015 (n = 116 group practices). These 116 excluded practices were primarily solo practitioners (91.8%) and had average Medicare payments of only $10,285 for 2015.

Characterizing group practice contexts

We characterized practices based on an established framework for thinking about relationships between practice context and healthcare delivery.6–8 Practices with 1 or 2 urologists were considered a “solo” practice. For those comprised of 3 or more physicians, practices in which the majority of physicians were urologists were regarded as “single specialty groups”. For these practices, we further characterized them based on size. Those with fewer than 10 urologists were categorized as “small” and those with 10 or more urologists were categorized as “large”. Group practices in which the minority of physicians were urologists were labeled “multispecialty groups.”

We then characterized these practices in a manner to test specific hypotheses related to payment reform. First, we hypothesized that groups who earned less of their Medicare revenue from procedures (i.e., an office-based focus) would be disproportionately affected by the leveling change. At the practice level, we measured the proportion of all Medicare Part B payments due to one of the ten E&M codes. For each practice, this was calculated by dividing the sum of all payments for E&M visits by the sum of all Part B payments. We used price-standardized payments to eliminate any variation in payment related to geography.9 Second, we hypothesized that practices that treat a disproportionate share of complex patients (and thus potentially use level 4 more commonly), such as those affiliated with an academic medical center or medical school practice, might be negatively affected by the policy. Using data provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, we identified group practices are associated with a medical school or academic medical center.10

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the percentage change in Medicare Part B payment associated with the new payment policy. This outcome measure was calculated based on the pattern of billed E&M visits for each practice. Using prices from current payment policy, we measured total payments for all E&M visits. Next, we characterized these payments based on prices from the new 2021 payment rules (Table 1). Finally, we divided the difference in current and anticipated payments by the total Part B payments for each practice, thus measuring the percent change in Medicare Part B revenue that would result from the policy change for each practice. We chose this relative measure as our primary outcome to help standardize policy effects across practices of different sizes.

As part of the final rule, CMS created a new “add-on” code meant to increase reimbursement related to the inherent visit complexity of non-procedural specialty care.5 In essence, this add-on code can be billed with all level 2 through 4 E&M visits performed by urologists and would increase the revenues for these visits by a fixed amount (i.e., approximately $13 per visit). All analyses examined the effect of the policy change with and without this add-on code.

Statistical Analysis

We used Pearson’s chi-squared test to assess relationships between practice context and the percent change in Medicare Part B payments. We used multiple linear regression to identify practice characteristics associated with changes in Medicare payment. For these models, the dependent variable was the percent change in Part B payment measured at the practice level. Independent variables included group practice organization (e.g. solo, small single specialty, large single specialty and multispecialty), academic medical group status, and extent of a practice’s office focus.

All statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC) and Stata 15 (College Station, TX). All tests were two-tailed and alpha was set at 0.05. This study was deemed exempt from IRB approval.

Results

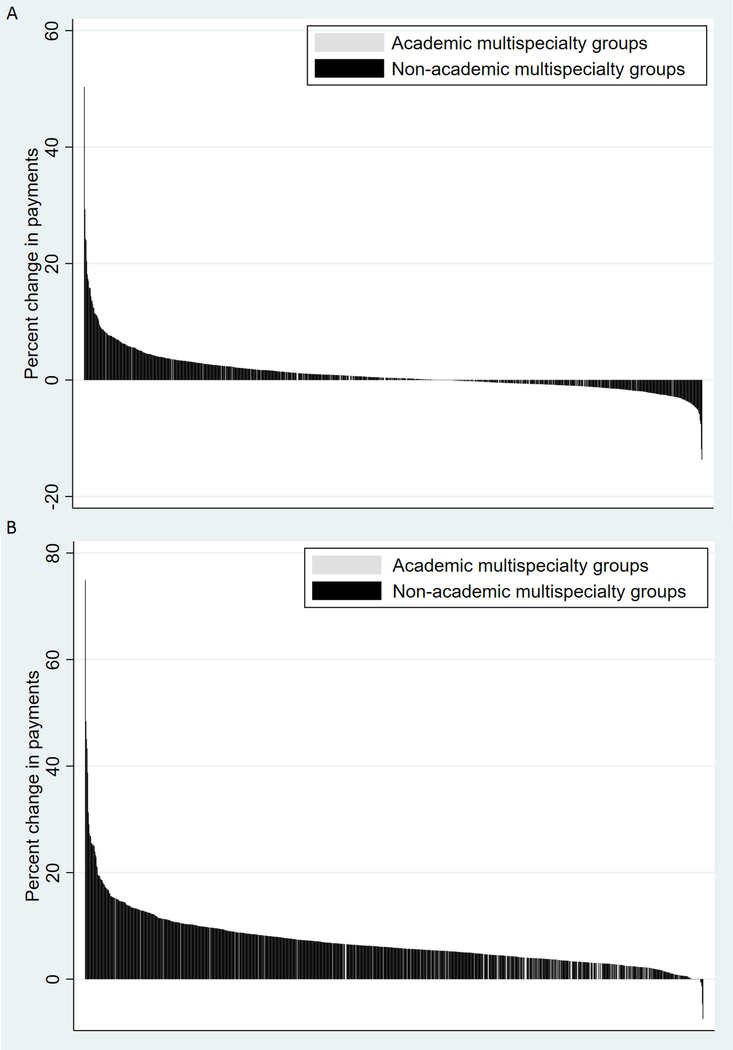

Of the 2,822 group practices with meaningful participation in the Medicare program, 1,372 (48.6%) were solo practices, 1,033 (36.6%) were multispecialty groups, 322 (11.4%) were small single specialty urology groups, and 95 (3.4%) were large single specialty groups. The distribution of visit types for each type of practice is depicted in the Supplemental Figure. Table 2 presents the characteristics and the percent change in Part B payments by group practice context. Under the 2021 payment rates, practices would have a net increase of 0.9% in Medicare Part B payments (range −20.4% to +50.3%) on average. With the add-on code, practices would realize a net increase of 6.8% (range −7.5% to +74.9%) of Medicare Part B revenue. Among the 1,789 practices primarily composed of urologists (i.e. excluding multispecialty groups), the median change in Medicare payment was +1.9% (range −20.4% to +48.7%). With the add-on code the average urology group would gain 7.9% (range −7.3% to +62.8%) in Part B payments. Figure 1 depicts the impact of the proposed policy on solo, small, and large urology group practices. The effect on solo practices varied the most, with a quarter losing at least 2.3% of Medicare part B payments while another quarter gaining 8.2% or more.

Table 2.

Characteristics of urology practices by group practice context

| Organization type | Solo | Small single specialty urology group | Large single specialty urology group | Multispecialty group | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of groups | 1,372 | 322 | 95 | 1,033 | |

| Total number of urologists | 1,534 | 1,497 | 2,004 | 4,351 | |

| Average number of physicians per practice, median (IQR) | 1 (1–1) | 4 (3–6) | 17 (13–28) | 76 (26–212) | <0.001 |

| Total Part B | 37,538 | 201,922 | 1,072,940 | 1,282,124 | <0.001 |

| revenues ($), median (IQR) | (21,082– 65,659) | (125,845– 338,595) | (525,244– 1,910,167) | (378,426– 3,497,657) | |

| Proportion of Part B revenues from office E&M visits, median (IQR) | .39 (.3– .47) | .35 (.29–.4) | .25 (.21–.31) | .3 (.23–.39) | <0.001 |

| Academic practices, n (%) | 1 ( 0.1%) | 3 ( 0.9%) | 5 ( 5.3%) | 107 (10.4%) | <0.001 |

| Percent change in Medicare Part B revenues, median (IQR) | |||||

| From E&M code change only | 2.7 (−2.3– 8.2) | 1.4 (−1.3– 4.1) | 0.55 (−0.95– 1.4) | 0.35 (−0.77–2.1) | <0.001 |

| E&M code change with add-on code | 8.9 (2.7– 16) | 7.2 (4–11) | 4.7 (3.2–6.3) | 5.9 (3.7–8.7) | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Impact of E&M payment changes on Medicare Part B payments for 1,789 urology group practices without (A) and with (B) new add-on code.

Among 1,033 multispecialty groups, the median change in Medicare Part B payments was +0.4% (range −13.7% to 50.3%). With the add-on code, the average multispecialty group would earn an additional 5.9% (range −7.5% to +74.9%). Figure 2 depicts the effect of the policy on all multispecialty groups, highlighting the 107 (10.4%) groups that were affiliated with an academic medical center. These academic multispecialty groups had a median change in Medicare Part B payment of +0.1% (range −2.8% to +8.1%) due to E&M leveling changes only. With the add-on code, the change was +3.7% and ranged from −0.1% to +15.1%.

Figure 2.

Impact of E&M payment changes on Medicare Part B payments for 1,033 multispecialty groups without (A) and with (B) new add-on code

In multiple regression analysis group organization and degree of office focus were significant independent predictors of the net impact in Part B payments (Supplemental Table). Academic medical center affiliation was independently associated with lower payments, but this was not statistically significant (−1.1%, 95% confidence interval [95%CI] −2.3 to 0.1, P=0.07). Compared to solo groups, all other group types would have significantly lower payments. Finally, with increasing office focus (for each 10% of Part B payments derived from E&M visits), a group would lose 0.2% of total Medicare Part B payments.

Discussion

Medicare’s change to office E&M visit payment, set to go into effect in 2021, will be beneficial for most urology practices if the policy is implemented as currently stated and payment for other sources of Part B revenue remain at current levels. On average, urology groups will increase Medicare Part B payments by between 0.9% and 6.8%. Smaller practices stand to benefit the most, but these groups will also have the most heterogeneity in the policy’s impact. While there is some concern that practices treating complex patients might be disproportionately affected, academic affiliation was not associated with diminished Medicare Part B payments.

Medicare’s physician fee schedule payment rules for office E&M visits have long been a source of dissatisfaction for physicians.11,12 The documentation requirements associated with E&M visit levels have been implicated in creating busy work for physicians,11 in motivating the development of billing-centric electronic medical record systems,13 and in worsening physician burnout.14 CMS’s efforts to simplify the documentation and payment system might have been well received, but for concerns about reduced reimbursement for physicians.15 While CMS’s analysis in the final rule suggests that the policy change will not meaningfully affect the distribution of payments among various medical specialties, there is the potential for significant effects on a subset of practices.

We found that urology practices would, on average, benefit from the proposed changes in office visit reimbursement. However, there is considerable heterogeneity in the effect of this policy among individual practices, particularly among solo practices. Therefore, urology groups may estimate the impact of this payment change by examining their own Medicare billing patterns and using the current and future payment rates in Table 1. By setting the payments for levels 2 through 4 office E&M visits to a single rate that is between the current payment for level 3 and level 4 visits, this policy increases Part B payments for practices that bill mostly level 2 and 3 visits and reduce total revenue for those that bill a disproportionate share of level 4 visits. As surgical specialists who generate revenue both from office visits and procedures, urologists may not be affected to the same degree as non-procedural physicians who rely solely on revenue from office visits.

Interestingly, there are some practices that stand to see large gains or losses in total Medicare Part B payments, with shifts of over 20% in either direction. Solo urology practices appear to be especially vulnerable to large changes as a result of policy. This is likely because solo practices tend to generate a larger proportion of their revenue from office visits. Conversely, larger urology groups may moderate the impact of this payment change by generating more revenues from procedures. Not only are office visits payments a small part of the overall revenue for these practices, but they often lead to additional procedures, which may further mitigate any negative effects of the payment policy changes.

In this study, we assessed the effects of E&M visit payment changes with and without the use of the newly created add-on code. CMS has indicated that these E&M payment changes should be budget neutral, and in the initial proposed rule, had included reductions to counteract the additional payments associated with the add-on code.16 However, in the final rule, these payment reductions were removed.5,17 Because it is unlikely that CMS plans to globally increase physician payments, we anticipate that subsequent policy will reduce payments for other Physician Fee Schedule services in order to achieve budget neutrality. As those anticipated reductions and their effects across practice contexts are unknown, we expect that the payment changes modeled here represent the upper bound of the actual effect that can be expected once the policy is implemented.

This analysis assumes that E&M leveling patterns will remain stable once new payment policy is implemented. Whether this is true or not is unclear. Incentives created by this new payment policy favor the provision of a higher volume of low-level (i.e. simpler and shorter) office visits. It is possible that some group practices will elect to increase the volume of visits and limit longer visits to maximize revenues. Such a shift could worsen access for complex patients who need high-level medical decision-making or the management of multiple chronic issues. If practices attempt to focus office visits on one or two problems and schedule multiple visits for complex patients who require additional care, it could create an additional financial and logistical burden on patients.

Conclusions

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule 2019 rule alters longstanding reimbursement rates for office E&M visits. Overall, urology practices stand to increase Medicare Part B payments as a result of this policy change. By simplifying the leveling system, this policy change may create financial pressures on multispecialty academic groups and groups that see disproportionately complex patients. Depending on their current practice patterns, solo urology practices may see large shifts in their Medicare revenue as a result of this new policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NCI F32CA232332 (PKM) and AHRQ R01HS025707 (VBS, BKH). The views expressed in this article do not reflect the views of the federal government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Part B Physician/Supplier National Data - CY2017 Top 200 Level 1 Current Terminology (HCPCS/CPT) Codes. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareFeeforSvcPartsAB/Downloads/LEVEL1CHARG17.pdf?agree=yes&next=Accept. Accessed 9/27/2018.

- 2.1995. DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT SERVICES. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed 10-30-18.

- 3.1997. DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES FOR EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT SERVICES. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed 10-30-18.

- 4.Brett AS. New guidelines for coding physicians’ services--a step backward. N Engl J Med 1998;339(23):1705–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medicare Program: Revisions to Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2019; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Quality Payment Program; Medicaid Promoting Interoperability Program; etc. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/11/23/2018-24170/medicare-program-revisions-to-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other-revisions. Accessed 11/16/18.

- 6.Casalino LP. Which type of medical group provides higher-quality care? Ann Intern Med 2006;145(11):860–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casalino LP, Ramsay P, Baker LC, Pesko MF, Shortell SM. Medical Group Characteristics and the Cost and Quality of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Health Serv Res 2018;53(6):4970–4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollenbeck BK, Kaufman SR, Yan P, et al. Urologist Practice Affiliation and Intensity-modulated Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer in the Elderly. Eur Urol 2018;73(4):491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/medcrephysfeeschedfctsht.pdf. Accessed 10-30-18.

- 10.Welch WP, Bindman AB. Town and Gown Differences Among the 100 Largest Medical Groups in the United States. Acad Med 2016;91(7):1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson RA, Basch P, Sussex A. Revisiting E&M visit guidelines--a missing piece of payment reform. N Engl J Med 2011;364(20):1892–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassirer JP, Angell M. Evaluation and management guidelines--fatally flawed. N Engl J Med 1998;339(23):1697–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berenson RAaL Alan. The False Choice Of Burden Reduction Versus Payment Precision in The Physician Fee Schedule. In. Health Affairs Blog 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin SA, Sinsky CA. The map is not the territory: medical records and 21st century practice. Lancet 2016;388(10055):2053–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Z, Goodson JD. The CMS Proposal to Reform Office-Visit Payments. N Engl J Med 2018;379(12):1102–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revisions to Payment Policies under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, Quality Payment Program and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1693-P.html. Accessed 11/1/2018.

- 17.Final Policy, Payment, and Quality Provisions Changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for Calendar Year 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/final-policy-payment-and-quality-provisions-changes-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-calendar-year. Accessed 11/01/18.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.