Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this repeated measures study was to examine the roles of cultural mistrust and perceived mentor support for ethnic/racial identity in a sample of girls of color. It was hypothesized that mentors’ support for ethnic/racial identity measured at baseline would influence relationship quality, as well as the girls’ ethnic identity and cultural mistrust at the end of the intervention, adjusting for baseline measures. It was also hypothesized that girls’ cultural mistrust toward Whites at baseline would be negatively associated with mentoring relationship quality at the end of the intervention.

Methods

Participants were 40 adolescent girls of color who were matched with racially/ethnically diverse women mentors in a community-based mentoring program.

Results

Mentor support for ethnic/racial identity as reported by youth significantly predicted relative increases in youth reports of relational but not instrumental satisfaction. Higher mentor support for ethnic/racial identity also significantly predicted increases in ethnic identity exploration, but only among girls with White mentors. Further, youth reported greater cultural mistrust toward Whites was a significant predictor of decreased instrumental relationship satisfaction among girls with White mentors.

Conclusions

Findings support the importance of further efforts to understand the roles of culturally-relevant relationship processes and youth attitudes in mentoring interventions for girls of color.

Keywords: Mentoring Relationships, Girls of Color, Ethnic/Racial Identity, Cultural Mistrust

Background

Youth mentoring has been found to be a promising intervention in promoting positive youth development and preventing negative outcomes, but the effects are modest (DuBois, Portillo, Rhodes, Silverthorn, & Valentine, 2011). It is important to understand the processes that make these interventions more effective. Mentoring relationship quality has been found to be a key component of effective mentoring, not simply the presence of a mentor (Deutsch & Spencer, 2009). Relationships that are characterized by close and meaningful bonds, mutuality, trust and empathy are viewed as the catalyst for positive developmental pathways (i.e., social, cognitive, identity) leading to healthy outcomes (Rhodes, 2002). However, mentor and mentee characteristics may influence mentoring relationship quality (Rhodes, 2002).

Researchers have begun to examine the roles of mentor and youth characteristics in shaping mentoring relationships. For example, researchers found that mentor self-efficacy beliefs, assessed prior to the start of mentoring in Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS), were significantly associated with more mentor-youth contact, greater involvement in program activities, fewer relationship obstacles and more perceived benefits for youth one year later (Parra, DuBois, Neville, & Pugh-Lilly, 2002). Another study found that mentor self-efficacy was positively associated with mentoring relationship quality as reported by mentors (Karcher, Nakkula & Harris, 2005). With regard to youth characteristics, a study of natural mentoring relationships of former foster care youth revealed that adolescents with less attachment insecurity reported closer mentoring relationships (Zinn, 2017). Another study found that children’s and adolescents’ baseline relationship quality with parents, teachers and peers influenced the extent to which they benefited from their BBBS mentoring relationships over time (Schwartz, Rhodes, Chan, & Herrera, 2011). Overall, research demonstrates that mentor and youth characteristics are related to mentoring relationship quality and outcomes, but little is known about the role of racial, ethnic, and cultural characteristics of mentors and youth.

Mentoring & Girls of Color

Although mentoring programs, such as BBBS, primarily serve youth of color (Valentino & Wheeler, 2013), little is known about how racial and cultural factors influence the mentoring experiences of this population (Sánchez, Colon-Torres, Feuer, Roundfield, & Berardi, 2014). The focus of this investigation is on girls of color, who are often marginalized in settings in which they interact with adults. For instance, in comparison to White girls, girls of color tend to experience harsher disciplinary policies in schools, are more likely to be involved with the justice system, and are more likely to be victims of gender-based violence (Clonan-Roy, Jacobs, & Nakkula, 2016). Given the failure and negative bias of adults in various settings serving girls of color, girls’ perceptions of adults may influence the quality of their mentoring relationships.

Our study is grounded in an adapted and combined model of positive youth development and critical race feminism for understanding the experiences of girls of color (Clonan et al., 2016). Clonan-Roy et al. (2016) argue that the development of girls of color is influenced by how society marginalizes them because of the intersection of their racial, ethnic, and gender identities. Although there are within-group differences in the experiences of girls of color, a commonality is that their non-White ethnic/racial identity marginalizes them in the U.S. relative to White girls (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016). Mentoring interventions have the potential to promote the resistance and resilience of girls of color through the provision of safe spaces and supportive, close relationships with adult women (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016). In fact, research shows that girls have unique challenges when they enter mentoring programs. For example, in a study of 1,138 racially/ethnically diverse adolescents in BBBS, girls were found to be more mistrustful of their parents and to have higher scores on parental alienation at baseline compared to boys (Rhodes, Lowe, Litchfield, & Walsh-Samp, 2008). The study findings also suggested that girls in long-term mentoring relationships perceived their mentors as more helpful compared to boys and girls in shorter-term relationships (Rhodes et al., 2008).

Culturally-Relevant Mentor & Youth Characteristics and Outcomes

Developing a positive ethnic/racial identity is an important developmental task for youth of color (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), and girls of color in particular engage in meaning-making about their multiple identities during adolescence (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016). Thus, it is important for mentoring programs targeting girls of color to examine whether and how their interventions influence mentees’ ethnic/racial identity development (Sánchez et al., 2014). Research suggests that merely the presence of natural mentors predicted a more positive racial identity among African American adolescents (Hurd, Sánchez, Zimmerman & Caldwell, 2012). Most of the mentors were non-parental family members and thus likely also African American, suggesting the possibility that these mentors helped with youth’s racial socialization, which may have promoted positive racial identity (Hurd et al., 2012). Another study found that mentors’ cultural skills played a role in ethnic identity. Specifically, an investigation of a mentoring program for girls of color revealed that more mentor ethnocultural empathy (i.e., one’s empathy toward people of a different racial/cultural group; Wang et al., 2003) was associated with higher ethnic identity exploration in girls (Peifer, Lawrence, Williams, & Leyton-Armakan, 2016), regardless of whether the mentor was White or a woman of color. Researchers have yet to examine the support that mentors provide to youth on their ethnic/racial identity, which may influence mentoring relationship quality as well as girls’ ethnic/racial identity itself.

Although Peifer et al. (2016) did not find that mentor race influenced the association between ethnocultural empathy and ethnic identity exploration, theory suggests that mentor race (White vs. person of color) may actually moderate the association between other mentor cultural skills and mentee ethnic identity. Because of the marginalization of people of color in the U.S., they typically engage in meaning-making about their racial and ethnic experiences compared to that of other individuals and groups (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Their racial and ethnic identity development may include exploration of the meaning of their race or ethnicity, the importance of their race or ethnicity to who they are, their own evaluations about their group or their sense of belonging to the group, and the perceptions of what others may think about their group (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Identity development is different for White people because of their dominant status in the U.S. White identity models include the cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses to issues of race and racism in the U.S. (e.g., an awareness of racism and one’s White privilege, the extent to which a person engages in anti-racist work; Helms, 1990). Given that the focus of this study is on girls of color, the lived experiences of mentors of color versus White mentors may influence the associations among mentor support for ethnic/racial identity, relationship quality and girls’ ethnic identity.

Although researchers have not examined mentor support for mentees’ ethnic/racial identity, some have investigated the role of mentor cultural skills in mentoring relationship quality. In qualitative interviews of participants of a BBBS mentoring program, findings suggested that some relationships terminated early in part due to the inability of mentors to bridge cultural differences (Spencer, 2007). Although some mentors discussed perceived discrepancies between their values and those of their mentees, findings suggested that these mentors were not prepared to respond effectively to such differences. Other mentors appeared to be unaware that relationship misunderstandings between them and their mentees seemingly stemmed from cultural differences; in some instances, mentors also seemed to harbor prejudicial stereotypes that negatively influenced their relationships. In a quantitative study of volunteer mentors, higher mentor multicultural competence predicted more satisfaction with their mentoring relationships with youth, after controlling for mentor demographic characteristics (Suffrin, Todd, & Sánchez, 2016). Although the association between mentors’ ethnocultural empathy and mentee satisfaction with the mentoring relationship was not significant overall in a study predominantly including girls of color, the association was found to be significantly stronger in cross-race than in same-race relationships (Leyton-Armakan, Lawrence, Deutsch, Williams, & Henneberger, 2012). Overall, research suggests the importance of mentors’ cultural skills in the quality of their relationships with youth.

In addition to mentor characteristics, it is important to examine what youth bring to mentoring relationships. Because of the multiple forms of oppression (based on race, ethnicity and gender) that girls of color experience (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016) and that both boys and girls of color report experiencing discrimination by adults (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006), girls of color may harbor cultural mistrust towards Whites, which may influence their relationships with White mentors. The importance of cultural mistrust in mentoring relationships is in line with theory and research that identifies feelings of trust as critical to youth mentoring relationships (e.g., Rhodes, Reddy, Roffman, & Grossman, 2005). Cultural mistrust, as examined with African American adults in counseling contexts, has been conceptualized as an outgrowth of the historical oppression that African Americans have experienced in the U.S. It refers to distrust toward social, institutional, and/or personal contexts controlled by Whites as well as toward White persons in positions of authority (Irving & Hudley, 2008). Research on the cultural mistrust of African Americans generally reveals that more cultural mistrust is associated with more negative views toward White counselors (Whaley, 2001). Given similarities between therapeutic and mentoring relationships (Spencer & Rhodes, 2005), cultural mistrust may serve as a barrier in youth’s relationships with White mentors.

In research on cultural mistrust conducted with adolescents, Albertini (2004) found that 35-50% of a sample of 359 West Indian and Haitian adolescents reported moderate to high levels of cultural mistrust. Among 9th-grade participants, it was found that greater reports of cultural mistrust were associated with having spent more time in the U.S. It is, therefore, possible that other groups, such as Latinas and Native Americans, also experience cultural mistrust because of the historical oppression targeting these groups in the U.S..

An experimental investigation of simulated mentoring relationships revealed that African American college students’ cultural mistrust was negatively related to their perceptions of White mentors’ credibility and cultural competence (Grant-Thompson & Atkinson, 1997). Given this association between cultural mistrust and perceptions of mentors, cultural mistrust may be related to mentee perceptions of mentor support for ethnic/racial identity and mentoring relationship quality. The complexity of findings in this area suggests that the association between youth cultural mistrust and mentoring relationship quality and girls’ perceptions of their mentors’ support for their ethnic/racial identity is worthy of further investigation.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

Mentoring is a promising intervention for promoting positive developmental trajectories for girls of color (Deutsch, Wiggins, Henneberger, & Lawrence, 2013). To adequately address the needs of girls of color, it is necessary to investigate the roles of girls’ cultural mistrust and mentor support on girls’ ethnic/racial identity. To address gaps in the literature, we conducted a repeated-measures study and hypothesized that higher youth-reported mentor support for ethnic/racial identity three months into their mentoring relationships would predict better relationship quality as well as higher ethnic identity and less cultural mistrust 12 months later, adjusting for baseline levels of these variables. We also explored whether the hypothesized relationships between mentor support for ethnic/racial identity and outcomes differed by mentor race. Given that the meaning of ethnic/racial identity and that its development varies for people of color versus Whites in the U.S. (Helms, 1990), we expected that the influence of the support that women of color mentors provide on ethnic/racial identity would be different than for White mentors. Specifically, it was expected that the association between mentor support for ethnic/racial identity and girls’ ethnic identity would vary by mentor race. That is, the association would be stronger for girls with women of color mentors than those with White mentors. Given the potential of cultural mistrust as a barrier in youth’s mentoring relationships, we hypothesized that more youth cultural mistrust toward Whites would predict poorer quality mentoring relationships with White mentors. Finally, we expected that more cultural mistrust would predict lower youth-reported mentor support for ethnic/racial identity.

Method

This study was part of a larger evaluation of an intervention (Current Author, 2008) designed for female mentees and mentors in a BBBS community-based mentoring program in a large city in the Midwest. In the larger study, half of the girls (n=20) were randomly assigned to mentoring as usual, whereas the other half was randomly assigned to mentoring plus enhancements. All of the mentors were community volunteers and screened according to standard BBBS procedures which included an in-person interview, criminal background check, and references. After the mentors were enrolled in BBBS, they were asked whether they wanted to participate in the study and be randomly assigned to one of the conditions. All of the mentors in the study received the standard 2-hour training of BBBS, and the mentors in the experimental condition received an additional 3-hour training and orientation. Because the current study was not focused on testing the experimental versus the control conditions, group assignment was included as a control variable in all analyses.

Participants

Participants were 40 girls newly matched with 40 women volunteer mentors. The youth mean age was 11.75 (SD = 1.26). The girls identified as African American/Black (n= 25; 63%), Latina (n=9; 23%), Asian American (n=1; 3%), Biracial (n=4; 10%), or Other (n=1; 3%). The majority (n=28; 70%) lived in single-headed female households and came from low-income families (n=34; 85% of households earned $30,000 or less).

The adult women volunteers, serving as mentors, had a mean age of 30.5 (SD = 5.11) and identified as White (n=21; 55%), African American/Black (n= 9; 22.5%), Latina (n=4; 10%), Asian-American (n=2; 5%), Native American/American Indian (n = 1; 3%) or Biracial (n=3; 8%). The majority (83%) reported working full-time, had at least a Bachelor’s degree (75%) and reported household incomes of at least $30,000 (85%). Of the girls with women of color mentors, 12 (63%) were in same-race relationships (e.g., African American girl with African American mentor) while 7 were in cross-race relationships.

Procedure

Youth were surveyed prior to the start of the intervention in the larger study (Time 1), three months later (Time 2), and one year after baseline, which coincided with the end of the intervention (Time 3). Participants completed surveys in a private office, with the survey read aloud in case there were any reading difficulties. Youth received $10 for each survey completed. There was no attrition in the study sample. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Mentor support for ethnic/racial identity

At Times 2 and 3, youth completed a six-item measure that assessed the extent to which they perceived that their mentor supported their racial/ethnic background, culture and identity. The measure was developed for this research, and sample items are: “My Big is respectful of my racial/ethnic background and culture,” “My Big makes me feel proud of my racial/ethnic background and culture,” and “My Big helps me learn new things about my racial/ethnic background and culture.” Responses are on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1=Not at all True to 4=Very True) with one reverse-scored item. A mean score was calculated for each participant, with higher scores indicating more mentor support for ethnic/racial identity. The scale showed good internal consistency (αs = .77 and .87 at Times 2 and 3).

Mentoring relationship quality

Girls completed two subscales from the Youth Mentoring Survey (Harris & Nakkula, 2004) at Times 2 and 3. Responses are on a Likert-type scale (1= Not True at all to 4= Very True). The subscales were Relational Satisfaction, a measure of how satisfied the mentee is with the relational aspects of the relationship (6 items; e.g., “My mentor really cares about me”; α = .91) and Instrumental Satisfaction, a measure of the mentee’s perceptions that the relationship has helped them grow and develop (6 items; e.g., “I have learned a lot from my mentor”; α = .80),. Responses on each item were added and divided by the total number of items in each subscale to create a scale score for each participant.

Cultural mistrust

Girls’ cultural mistrust toward Whites was assessed using a modified version of the Interpersonal Relations subscale of the Cultural Mistrust Inventory (Terrell & Terrell, 1981), which was a 13-item subscale originally developed for Black adults and measures the extent to which individuals are suspicious of Whites in interpersonal and social contexts. The modified subscale was administered at Times 1 and 3. Modification involved rewording some items to make them developmentally appropriate for an adolescent sample (e.g., “cautious” was changed to “careful”) and to reduce the number of reverse-scored items. The scale was also modified for use with a diverse sample (e.g., “It is best for Blacks to be on their guard when among Whites” changed to “People from my ethnic/racial group should be on their guard…”). The subscale was reduced to 11 items, and the response scale was changed to a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree). A sample item is, “People from my ethnic/racial group should be suspicious of a White person who tries to be friendly.” Four of the items are reversed scored. A mean score was calculated for each participant, and higher scores on the scale indicate more mistrust (Time 1 α = .78; Time 3 α = .91).

Ethnic identity

Roberts et al.’s (1999) Revised Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure was administered at Times 1 and 3. This measure has two subscales: affirmation/belonging, which includes seven items that ask about commitment and sense of belonging to one’s ethnic group and one’s sense of pride/positive feelings about the group (e.g., “I am happy that I am a member of the group I belong to”), and exploration, which includes five items focused on the process of learning about and becoming involved in one’s ethnic group (e.g., “I have spent time trying to find out more about my own ethnic group”). Responses are on a four-point, Likert-type scale (1=Strongly Disagree to 4=Strongly Agree), and mean scores were calculated for each participant on each subscale, with higher scores indicating a higher ethnic identity (affirmation/belonging αs = .65 and .87 for Times 1 and 3, respectively, and exploration αs = .63 and .71, respectively).

Data Analysis

A series of multiple hierarchical regression analyses was conducted to test study hypotheses. For hypotheses regarding mentor support for ethnic/racial identity as a predictor of relationship quality, ethnic identity and cultural mistrust, the specific outcome variables measured at Time 1 or 2 (T1 or T2) and group assignment (experimental vs. control) were entered in the first block as control variables. In the second block, mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T2 was entered. In the third block, the interaction between mentor support for ethnic/racial identity and mentor race (white vs. woman of color) was entered. The outcome variables in each of the regressions were measured at Time 3 (T3). For the hypotheses about cultural mistrust as a predictor of mentoring relationship quality and perceptions of mentor support for ethnic/racial identity, only the 21 girls with White mentors were included in the analyses. The outcome variables measured at T2 and group assignment (experimental vs. control) were entered in the first block as control variables. Cultural mistrust was then entered in the second block at T1.

Results

Descriptive statistics for measures were calculated, and bivariate Pearson correlations were conducted with the key study variables (see Table 1). Significant associations presented are at the p < .05 or .01 level. As shown in Table 1, mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T1 and T2 were positively and significantly associated with both relational and instrumental satisfaction, but were not significantly associated with either of the ethnic identity subscales at T1 or T3. Among girls with White mentors, cultural mistrust at T1 was negatively and significantly associated with mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T1 and T3. However, cultural mistrust at T3 was not significantly associated with mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T1 or T3.

Table 1.

Correlations of Study Variables

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cultural Mistrust T1 a | 1.50 (43) | — | .28 | −.59** | −.59** | .05 | −.69** | −.12 | −.42† | −.09 | −.35 | −.21 | −.52* |

| 2. Cultural Mistrust T3 a | 1.65 (.71) | — | −.23 | −.42a | .04 | .01 | −.33 | −.14 | −.27 | −.55* | −.36 | −.47* | |

| 3. Mentor Support−ERI T2 | 2.23 (.89) | — | .77** | .15 | .25 | .15 | .09 | .54** | .52** | .44** | .42* | ||

| 4. Mentor Support−ERI T3 | 2.31 (.83) | — | .18 | .23 | −.02 | .13 | .33* | .72** | .40* | .68** | |||

| 5. EI – Exploration T1 | 2.85 (.57) | — | .17 | .27 | −.06 | −.24 | .09 | −.06 | .05 | ||||

| 6. EI − Exploration T3 | 3.12 (.59) | — | −.01 | −54** | .01 | .00 | .01 | .28 | |||||

| 7. EI – Affirmation & Belonging T1 | 3.44 (.40) | — | .11 | .05 | −.12 | .14 | .05 | ||||||

| 8. EI−Affirmation & Belonging T3 | 3.51 (.45) | — | −.08 | .20 | −.11 | .17 | |||||||

| 9. RQ: Relational Satisfaction T2 | 2.48 (.72) | — | .36* | .73** | .54** | ||||||||

| 10. RQ: Relational Satisfaction T3 | 2.56 (.72) | — | .32 | .73** | |||||||||

| 11. RQ: Instrumental Satisfaction T2 | 1.54 (.86) | — | .62** | ||||||||||

| 12. RQ: Instrumental Satisfaction T3 | 1.89 (.89) | — |

ERI – Ethnic/Racial Identity; EI – Ethnic Identity; RQ − Relationship Quality; T1: baseline; T2: 3 months after baseline; T3: one year after baseline;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.10;

Only mentees (n = 21) with White mentors were examined in correlations with cultural mistrust towards Whites.

The role of mentor support for ethnic/racial identity

As shown in Table 2, higher reported mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T2 significantly predicted higher relational satisfaction at T3, controlling for relational satisfaction at T2 and group assignment. There was not a significant interaction between mentor race and support for ethnic/racial identity. For instrumental satisfaction, neither mentor support for ethnic/racial identity nor its interaction with mentor race was a significant predictor.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Mentor Support for Ethnic/Racial Identity (ERI) at Time 2 Predicting Mentoring Relationship Quality at Time 3 (N=36)

| Mentoring Relationship Quality: Relational Satisfaction T3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | ΔF |

| Block 1 | .16 | 3.04 | |||

| Relational Satisfaction T2 | .43 | .20 | .35* | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .22 | .23 | .16 | ||

| Block 2 | .16 | 3.63* | |||

| Relational Satisfaction T2 | .24 | .20 | .19 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .15 | .22 | .10 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .36 | .14 | .42* | ||

| Mentor Race | .09 | .22 | .06 | ||

| Block 3 | .03 | 1.33 | |||

| Relational Satisfaction T2 | .22 | .20 | .18 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .25 | .23 | .17 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .21 | .19 | .24 | ||

| Mentor Race | −.69 | .71 | −.48 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI × Mentor Race | .32 | .28 | .62 | ||

| Mentoring Relationship Quality: Instrumental Satisfaction T3 | |||||

| Block 1 | .42 | 12.01** | |||

| Instrumental Satisfaction T2 | .60 | .15 | .56** | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .36 | .24 | .21 | ||

| Block 2 | .05 | 1.35 | |||

| Instrumental Satisfaction T2 | .53 | .16 | .49** | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .36 | .24 | .21 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .24 | .15 | .23 | ||

| Mentor Race | −.10 | .24 | −.06 | ||

| Block 3 | .00 | .09 | |||

| Instrumental Satisfaction T2 | .53 | .16 | .49** | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .39 | .27 | .22 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .20 | .21 | .19 | ||

| Mentor Race | −.32 | .79 | −.18 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI × Mentor Race | .09 | .31 | .14 | ||

p<.01;

p<.05;

ERI – Ethnic/Racial identity; Mentor Race (White vs. Woman of Color)

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses showed that higher mentor support of ethnic/racial identity at T2 predicted higher ethnic identity exploration at T3, controlling for ethnic identity exploration at T1 and group assignment (see Table 3). There was also a significant interaction between mentor support for ethnic/racial identity and mentor race in predicting ethnic identity exploration (see Table 3). Because mentor race was coded as 0 for girls with a White mentor, the coefficient in this regression for mentor support for ethnic/racial identity represented the estimated association of this variable with identity exploration (Aiken & West, 1991). To derive the corresponding estimate for girls with a woman of color mentor, the coding of the mentor race was simply reversed, such that girls matched with a woman of color mentor were coded as 0 (Aiken & West, 1991). Note that degrees of freedom for the tests of the coefficients for mentor support for ethnic/racial identity as a predictor of identity exploration within each group correspond to the full sample size less the number of predictors and intercept to accommodate the use of the full sample for analyses (Aiken & West, 1991).

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Mentor Support for Ethnic/Racial Identity (ERI) Predicting Ethnic Identity Subscales and Cultural Mistrust a (N=40)

| Ethnic Identity: Exploration T3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | ΔF |

| Block 1 | .05 | .94 | |||

| Ethnic Identity: Exploration T1 | .12 | .17 | .12 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .16 | .19 | .15 | ||

| Block 2 | .05 | 1.03 | |||

| Ethnic Identity: Exploration T1 | .09 | .17 | .10 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .16 | .20 | .15 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .14 | .10 | .22 | ||

| Mentor Race | −.11 | .18 | −.10 | ||

| Block 3 | .21 | 10.02** | |||

| Ethnic Identity: Exploration T1 | .13 | .15 | .13 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | −.03 | .18 | −.02 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .50 | .15 | .80** | ||

| Mentor Race | 1.30 | .48 | 1.17* | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI × Mentor Race | −.62 | .20 | −1.48** | ||

| Ethnic Identity: Affirmation & Belonging T3 | |||||

| Block 1 | .02 | .38 | |||

| Ethnic Identity: Affirmation & Belonging T1 | .12 | .18 | .10 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .08 | .15 | .09 | ||

| Block 2 | .01 | .08 | |||

| Ethnic Identity: Affirmation & Belonging T1 | .11 | .19 | .09 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .08 | .16 | .09 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .03 | .09 | .06 | ||

| Mentor Race | −.03 | .15 | −.03 | ||

| Block 3 | .07 | 2.55 | |||

| Ethnic Identity: Affirmation & Belonging T1 | .07 | .19 | .07 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | −.00 | .16 | −.00 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .21 | .14 | .41 | ||

| Mentor Race | .62 | .44 | .70 | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI × Mentor Race | −.29 | .18 | −.86 | ||

| Cultural Mistrust T3a | |||||

| Block 1 | .26 | 3.16 | |||

| Cultural Mistrust T1 | .35 | .34 | .21 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | −.61 | .29 | −.43† | ||

| Block 2 | .02 | .38 | |||

| Cultural Mistrust T1 | .51 | .43 | .31 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | −.71 | .33 | −.50* | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .16 | .25 | .18 | ||

p<.01;

p<.05;

p=.05;

ERI – ethnic/racial identity; Mentor Race (White vs. Woman of Color); T1: baseline; T2: 3 months after baseline; T3: one year after baseline;

Only mentees (n = 21) with White mentors were examined in regression that included cultural mistrust as an outcome.

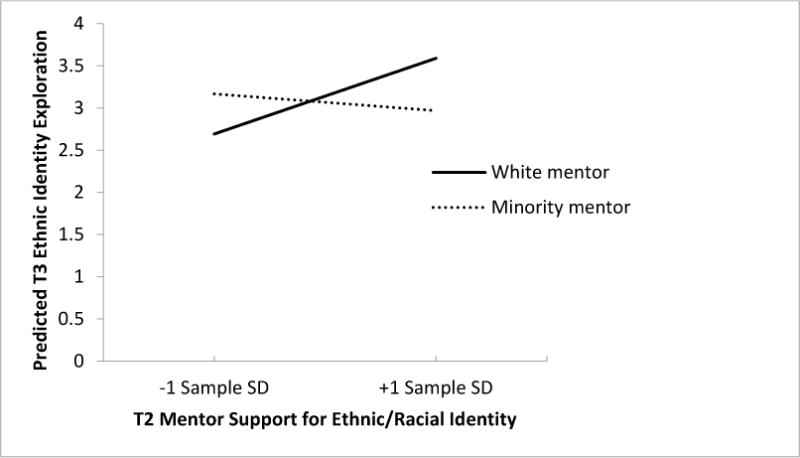

As shown in Figure 1, among girls with White mentors, greater reported mentor support for ethnic/racial identity predicted increased ethnic identity exploration, b = .50, standard error [SE] = .15, standardized regression coefficient [β] = .80, t(35) = 3.41, p < .01. In contrast, among girls with women of color mentors, the association was not significant, b = −.11, SE = .12, β = −.18, t(35) = −0.92, ns. These results indicate that the simple slope relating mentor support for ethnic/racial identity to identity exploration was positive and statistically significant for girls with White mentors. In contrast, it was negative, but not statistically significant, for girls with women of color mentors. Neither support for ethnic/racial identity nor its interaction with mentor race significantly predicted ethnic identity affirmation/belonging.

Figure 1.

Mentor race as a moderator of the association between mentor support racial/ethnic identity and girls’ ethnic identity exploration

Finally, a hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to examine the role of mentor support for ethnic/racial identity in the cultural mistrust of girls with White mentors. The hypothesis was not supported; mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T2 did not significantly predict cultural mistrust at T3 (see Table 3).

Role of Cultural Mistrust

As hypothesized, greater reported cultural mistrust towards Whites at T1 significantly predicted less instrumental satisfaction at T3, controlling for instrumental satisfaction at T2 and group assignment (see Table 4). Cultural mistrust at T1 did not significantly predict relational satisfaction nor mentor support for ethnic/racial identity at T3, however.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Cultural Mistrust Predicting Mentoring Relationship Quality and Mentor Support for Ethnic/Racial Identity (ERI) Among Girls with White Mentors (n=21)

| Mentoring Relationship Quality: Relational Satisfaction T3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | ΔF |

| Block 1 | .28 | 3.38† | |||

| Relational Satisfaction T2 | .49 | .29 | .36† | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .57 | .31 | .39† | ||

| Block 2 | .06 | 1.10 | |||

| Relational Satisfaction T2 | .44 | .28 | .33 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .51 | .31 | .34 | ||

| Cultural Mistrust T1 | −.42 | .35 | −.25 | ||

| Mentoring Relationship Quality: Instrumental Satisfaction T3 | |||||

| Block 1 | .56 | 10.94** | |||

| Instrumental Satisfaction T2 | .72 | .20 | .63** | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .41 | .33 | .22 | ||

| Block 2 | .11 | 5.16* | |||

| Instrumental Satisfaction T2 | .63 | .18 | .56** | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .37 | .30 | .20 | ||

| Cultural Mistrust T1 | −.73 | .32 | −.34* | ||

| Mentor Support for ERI T3 | |||||

| Block 1 | .43 | 6.49** | |||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .51 | .30 | .51* | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .38 | .33 | .25 | ||

| Block 2 | .09 | 3.12† | |||

| Mentor Support for ERI T2 | .26 | .24 | .26 | ||

| Group (Intervention vs. Control) | .47 | .31 | .29 | ||

| Cultural Mistrust T1 | −.71 | .40 | −.39† | ||

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10;

T1: baseline; T2: 3 months after baseline; T3: one year after baseline

Discussion

Grounded in a model of positive youth development and critical race feminism for girls of color (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016), our study centered the experiences of girls of color based on their ethnic, racial and gender identities. Although mentoring researchers and practitioners have called on the field to focus on the role of race in youth mentoring (Sánchez et al., 2014; Weiston-Serdan, 2017) and many mentoring programs serve primarily youth of color (Valentino & Wheeler, 2013), there has been relatively little empirical research on the topic. This study was the first to examine the role of mentor support for ethnic/racial identity in how girls of color experience their mentoring relationships over time as well as in their ethnic identity and cultural mistrust toward Whites, accounting for baseline measures of these variables.

Consistent with study hypothesis, we found that girls’ perceptions of their mentor support for ethnic/racial identity was significantly related to mentoring relationship quality, an important aspect of effective mentoring interventions (Rhodes, 2002). Specifically, more mentor support for ethnic/racial identity significantly predicted increases in satisfaction with the relational aspects of girls’ ties with mentors. However, it did not significantly predict more instrumental ties. Relational satisfaction focuses on feelings of warmth and closeness, whereas instrumental satisfaction focuses on learning and growth in the relationship. Given that ethnic/racial identity is an integral part of healthy adolescent development for youth of color (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), perhaps mentor support of girls’ ethnic/racial identity made mentees feel that mentors are supporting an important part of who they are. In turn, this support enhanced comfort and closeness in the relationship, and yielded closer bonds. In contrast, mentor support for ethnic/racial identity may not be as important in receiving mentors’ instrumental support, such as advice, among girls of color.

As expected, girls who reported more support from their mentor on their ethnic/racial identity showed increased ethnic identity exploration. Mentors who showed more support might have asked questions about girls’ race or ethnicity and engaged in activities to help girls learn about their identity. This finding is underscored by the positive academic and psychosocial outcomes fostered by a stronger ethnic identity in youth of color (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Interestingly, mentor support for ethnic/racial identity was not significantly associated with ethnic identity affirmation and belonging. There was a significant and negative association in this study between the exploration and affirmation/belonging subscales of the ethnic identity measure at T3. Based on Phinney’s (1992) theoretical model, and also given participants’ developmental stage of early adolescence, it is possible that girls have not yet begun to affirm their ethnic identity. Instead, they may be more focused on identity exploration. This possibility may explain why mentor support for ethnic/racial identity only significantly predicted ethnic identity exploration, and not affirmation and belonging.

We found that mentor race moderated the association between mentor support for ethnic/racial identity and ethnic identity exploration, but in the unexpected direction. Among girls with White mentors, as mentor support for ethnic/racial identity increased, ethnic identity exploration increased. The association was not significant for girls with women of color mentors, however. This is a puzzling finding and requires more investigation to fully explain. However, it is possible that girls’ ethnic identity was more salient in relationships with White mentors, given the cross-cultural and power differences between majority and minority status groups in the United States. In this case, interest and support from White mentors around ethnic identity may have been interpreted or perceived differently among their mentees relative to interest and support from women of color mentors. It is also possible that girls and women of color had a shared understanding about race and ethnicity and focused, through their relationship, on other aspects of girls’ ethnic/racial development, such as how to cope with racial discrimination. Surprisingly, mentor race did not moderate the association between support for ethnic/racial identity and ethnic identity affirmation/belonging. Again, perhaps there would have been an interaction effect if the girls were older and further in their ethnic identity development.

Given the critical role that feelings of trust hold in developing close and effective relationships between youth and adults (Rhodes et al., 2005), cultural mistrust is important, albeit complicated, to investigate in youth mentoring. Because of the nature and premise of the cultural mistrust scale, we only assessed it among girls with White mentors. Of note, girls’ cultural mistrust significantly predicted less instrumental satisfaction in relationships with White mentors over time, but not relational satisfaction. Perhaps girls’ cultural mistrust did not influence them to feel that their mentors care about them or their connection with White mentors, but did affect the extent to which they were satisfied with and/or approached their mentors for advice or problem solving. Cultural mistrust may thus serve as a barrier in further deepening relationships between girls of color and White mentors. If this is the case, these girls might turn to other adults for instrumental support as a result. This potential barrier is critical to address in mentoring interventions involving White mentors serving girls of color.

Limitations

In considering these complex study findings, several limitations are important to identify. The small sample size limited statistical power for detecting associations among variables as well as the generalizability of results. We suggest that our study is replicated in future research with larger samples to better understand the roles of culturally relevant relationship processes and youth attitudes. This research would be important to help identify avenues for strengthening the effects of mentoring for this population, particularly with consideration of the racial, ethnic and gender identities of girls of color. Another limitation is that the internal consistencies for some of the measures were lower at earlier time points compared to later ones. This may be due to cognitive changes during early adolescence, such that participants may have been more perceptive in differentiating between items later in the study. It also calls into question the ability of this study to reliably measure these important constructs (e.g., ethnic identity), and whether we were able to ascertain the effect of the predictors on outcomes over and above the outcomes at baseline. Further, our investigation only examined mentees’ perspectives. Future research should also examine these factors from mentors’ perspectives in order to provide a more complete picture of racial, ethnic and cultural mentor characteristics as well as relationship quality and outcomes.

Limitations notwithstanding, findings support past research focused on the importance of mentor and youth characteristics in mentoring relationship quality (e.g., Karcher et al., 2005; Zinn, 2017), and the role of mentors’ cultural skills in their relationships with girls of color (Leyton-Armaken et al., 2014; Peifer et al, 2016). While the mentoring literature has focused more attention on the differences in youth outcomes between cross- vs. same-race mentoring relationships (e.g., Rhodes, Reddy, Grossman, & Lee, 2002), this study responds to calls to examine racial/ethnic/cultural processes that influence mentoring relationships and outcomes (Albright, Hurd, & Hussain, 2017; Sanchez et al., 2014).

Implications

There are a number of implications based on this study. The current investigation was one of the first to examine the role of girls’ cultural mistrust in their relationships with mentors. Findings suggest that cultural mistrust may indeed serve as a barrier to relationships between female mentees of color and White mentors. This highlights the importance of providing training and supervision of cultural and relational dynamics in mentoring relationships between girls of color and White mentors, particularly for girls who harbor cultural mistrust. Given the significance of trust in effective mentoring relationships, practitioners would do well to consider girls’ cultural mistrust in the matching process and/or incorporate attention to this process in match supervision and support.

As suggested by previous researchers (Albright et al., 2017), it is also recommended that mentors are trained to support girls of color in their ethnic/racial identity development. Mentoring staff can train mentors to not only help girls explore their ethnic/racial identity, but to also affirm their identity and help girls of color develop a sense of belonging to their ethnic/racial group. As these trainings are provided, it is necessary that they are evaluated to explore their influence on relationship quality and, ultimately, youth outcomes. Ethnic/racial identity is critically important to the healthy development of youth of color (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). A positive ethnic/racial identity has also been found to buffer the negative effects of stressors and deleterious life events (e.g., racial discrimination; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014) in the lives of youth. Therefore, it is imperative that mentoring programs include a positive ethnic/racial identity, alongside traditional goals, such as academic achievement and preventing problem behaviors, as a goal of their programs. Prioritizing attention to these important interpersonal and intrapersonal experiences can support adult mentors in partnering with girls of color to ultimately help advance their resilience, resistance, and healthy successful development (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (5 R21 MH069564-03) awarded to David L. DuBois. The authors would like to thank Amy Anderson, Ali Mroczkowski, Kitty Beuhler, Danielle Vaclavik, Lynn C. Liao, Torie Weiston-Serdan and the anonymous reviewers who provided feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Bernadette Sánchez, DePaul University.

Julia Pryce, Loyola University Chicago.

Naida Silverthorn, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Kelsey L. Deane, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

David L. DuBois, University of Illinois at Chicago

References

- Albertini VL. Racial mistrust among immigrant minority students. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2004;21(4):311–331. [Google Scholar]

- Albright JN, Hurd NM, Hussain SB. Applying a social justice lens to youth mentoring: A review of the literature and recommendations for practice. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2017;59:363–381. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Clonan-Roy K, Jacobs CE, Nakkula MJ. Towards a model of youth development specific to girls of color: Perspectives on development, resilience, and empowerment. Gender Issues. 2016;33:96–121. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch NL, Spencer R. Capturing the magic: Assessing the quality of youth mentoring relationships. New Directions for Student Leadership. 2009;2009(121):47–70. doi: 10.1002/yd.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch NL, Wiggins AY, Henneberger AK, Lawrence EC. Combining mentoring with structured group activities: A potential after school context for fostering relationships between girls and mentors. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2013;33:44–76. doi: 10.1177/0272431612458037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Portillo N, Rhodes JE, Silverthorn N, Valentine JC. How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2011;12:57–91. doi: 10.1177/1529100611414806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Thompson SK, Atkinson DR. Cross-cultural mentor effectiveness and African American male students. Journal of Black Psychology. 1997;23:120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):218. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JT, Nakkula MJ. Youth Mentoring Survey (YMS) Fairfax, VA: Applied Research Consulting; 2003. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd N, Sánchez B, Zimmerman M, Caldwell C. Natural mentors, racial identity, and educational attainment among African American adolescents: Exploring pathways to success. Child Development. 2012;83:1196–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving MA, Hudley C. Cultural identification and academic achievement among African American males. Journal of Advanced Academics. 2008;19:676–698. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ, Nakkula MJ, Harris J. Developmental match characteristics: Correspondence between mentors’ and mentees’ assessments of relationship quality. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26(2):93–110. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-1847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyton-Armakan J, Lawrence E, Deutsch N, Williams J, Henneberger A. Effective youth mentors: The relationship between initial characteristics of college women mentors and mentee satisfaction and outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40:906–920. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21491.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parra GR, DuBois DL, Neville HA, Pugh-Lilly AO. Mentoring relationships for youth: A process-oriented model. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(4):367–388. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer JS, Lawrence EC, Williams JL, Leyton-Armakan J. The culture of mentoring: Ethnocultural empathy and ethnic identity in mentoring for minority girls. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2016;22(3):440–446. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE. Stand by me: The risks and rewards of youth mentoring relationships. Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Lowe SR, Litchfield L, Walsh-Samp K. The role of gender in youth mentoring relationship formation and duration. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2008;72(2):183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Reddy R, Grossman JB, Lee JM. Volunteer mentoring relationships with minority youth: An analysis of same-versus cross-race matches. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32(10):2114–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Reddy R, Roffman J, Grossman JB. Promoting successful youth mentoring relationships: A preliminary screening questionnaire. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26:147–167. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-1849-8.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, Schwartz SJ, Umana-Taylor AJ, French S, Yip T. Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic and health outcomes. Child Development. 2014;85:40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19(3):301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez B, Colón-Torres Y, Feuer R, Roundfield KE, Berardi L. Race, ethnicity, and culture in mentoring. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SEO, Rhodes JE, Chan CS, Herrera C. The impact of school-based mentoring youths with different relational profiles. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(2):450–462. doi: 10.1037/a0021379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R, Rhodes JE. A counseling and psychotherapy perspective of mentoring relationships. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. 1st. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R. “It’s not what I expected:” A qualitative study of youth mentoring relationship failures. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;22:331–354. [Google Scholar]

- Suffrin RL, Todd N, Sánchez B. An ecological perspective of mentor satisfaction with their youth mentoring relationships. Journal of Community Psychology. 2016;44:553–568. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape the intellectual identities and performance of women and African Americans. American Psychologist. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Terrell S. An inventory to measure cultural mistrust among Blacks. Western Journal of Black Studies. 1981;5:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino S, Wheeler M. Big Brothers Big Sisters report to America: Positive outcomes for a positive future. 2013 youth outcomes report. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.bbbs-gc.org/Websites/bbbsgallatincounty/images/20130425_BBBSA_YOS2013.pdf.

- Wang Y, Davidson MM, Yakushko OF, Savoy HB, Tan JB, Bleier JK. The scale of ethnocultural empathy: Development, validation and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50(2):221–234. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiston-Serdan T. Critical mentoring: A practical guide. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust: An important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2001;32(6):555–562. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn A. Predictors of natural mentoring relationships among former foster youth. Children & Youth Services Review. 2017;79:564–575. [Google Scholar]