Abstract

Background

Elderly patients are a growing and vulnerable group with an elevated perioperative risk. Perioperative treatment pathways that take these patients’ special risks and requirements into account are often not implemented in routine clinical practice.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search in PubMed, the AWMF guideline database, and the Cochrane database for guidelines from Germany and abroad, meta-analyses, and Cochrane reviews.

Results

The care of elderly patients who need surgery calls for an interdisciplinary, interprofessional treatment concept. One component of this concept is preoperative preparation of the patient (“prehabilitation”), which is best initiated before hospital admission, e.g., correction of deficiency states, optimization of chronic drug treatment, and respiratory training. Another important component consists of pre-, intra-, and postoperative measures to prevent delirium, which can lower the frequency of this complication by 30–50%: these include orientation aids, avoidance of inappropriate drugs for elderly patients, adequate analgesia, early mobilization, short fasting times, and a perioperative nutrition plan. Preexisting cognitive impairment predisposes to postoperative delirium (odds ratios [OR] ranging from 2.5 to 4.5). Frailty is the most important predictor of the postoperative course (OR: 2.6–11). It follows that preoperative assessment of the patient’s functional and cognitive status is essential.

Conclusion

The evidence-based and guideline-consistent care of elderly patients requires not only close interdisciplinary, interprofessional, and cross-sectoral collaboration, but also the restructuring and optimization of habitual procedural pathways in the hospital. Elderly patients’ special needs can only be met by a treatment concept in which the entire perioperative phase is considered as a single, coherent process.

The demographic trend in Germany means that an increasing number of elderly patients will undergo surgical procedures. More than 7 million inpatients aged 65 years or older underwent surgery in 2017 (e1). There is no standard definition for the age beyond which an individual is “old.” In medicine, one often refers to individuals aged 65–75 years as the “young elderly” and 75–85 years as the “old elderly.” Those aged over 85 years are occasionally referred to as “the aged” or “super-elderly.”

With advancing age, risks that can have an adverse effect on the postoperative outcome in this patient group accumulate. A good postoperative outcome is defined not only by surgical success, but far more so by the preservation of performance, functionality, autonomy, and quality of life. Avoiding postoperative delirium (POD) is an important treatment goal. POD has serious sequelae for the patient‘s future life, including a loss of quality of life and independence, as well as increased morbidity and mortality. As a result, this frequent complication (incidence among patients = 70 years: 30%–50%) has dramatic social, health-related, and socioeconomic consequences (1, e2– e4).

Methods

The evidence for the following recommendations on the perioperative care of older patients is primarily based on current guidelines, as well as on randomized controlled studies, meta-analyses, and systematic review articles (etable). A search was carried out in PubMed, the guideline database of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF), and the Cochrane database.

eTable. Assessment of evidence from relevant studies and guidelines.

|

Perioperative significance of frailty (first author, source) | ||

| Schmidt et al. 2018 (e10) |

Prospective cohort study; 131 patients; follow-up: 1 year postoperatively |

Higher 1-year mortality in patients with frailty (OR: 4.5; 95% CI: [1.2; 18.3]). Cognitive impairment associated with increased 1-year mortality (OR: 0.6; 95% CI: [0.4; 0.95]). Evidence level: moderate |

| Oakland et al. 2016 (e11) |

Meta-analysis; 12 studies, 7960 patients |

Frailty increases hospital mortality and (OR: 2.78; 95% CI: [1.6; 4.7]) 1-year mortality (OR: 1.99; 95% CI: [1.5; 2.7]). Evidence level: moderate–high |

| Watt et al. 2018 (3) | Meta-analysis; 44 studies, 12 281 patients |

Frailty (OR: 2.2; 95% CI: [1.3; 3.6]) and cognitive impairments (OR: 2.01; 95% CI: [1.4; 2.8]) are associated with the development of postoperative complications. Evidence level: moderate–high |

| Delirium | ||

| Aldecoa et al. 2017 (12) |

Guideline | Preoperative identification of risk factors and implementation of POD preventive measures recommended. Evidence level: high |

| Siddiqi et al. 2016 (1) | Meta-analysis (Cochrane); 39 studies, 16 082 patients |

Multicomponent programs are effective in POD prevention (versus standard care: RR: 0.69; 95% CI: [0.6; 0.8]). Evidence level: moderate–high |

| NICE Clinical Guideline 2010 (37) |

Guideline | Old age, cognitive impairment, and multimorbidity are significant risk factors for the development of POD. Evidence level: high |

| Perioperative nutrition | ||

| Weimann et al. 2013 Weimann et al. 2017 (38, 39) |

S3 Guidelines | Unnecessary perioperative fasting should be avoided, carbohydrate-containing drinks advisable preoperatively, perioperative nutritional therapy recommended in patients with malnutrition. Evidence level: high |

| Volkert et al. 2013, 2018 (17, 18) |

S3 Guideline | Malnutrition and frailty increase the postoperative complication rate and mortality, perioperative nutrition concepts recommended. Evidence level: high |

| Polypharmacy | ||

| Chow et al. 2012 Mohanty et al. 2016 (22, 27) |

Guidelines | Non-essential medication should be discontinued perioperatively in order to avoid medication-induced complications. Evidence level: moderate–high |

| Holt et al. 2010 (19) |

Qualitative literature analysis;expert group (Delphi) | Identification of 83 drugs as potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) for the elderly. Evidence level: moderate |

| AGS 2015 (20) |

Systematic literature search;expert group (Delphi) | Identification of drugs as potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) in the elderly. Evidence level: moderate–high |

| Anticoagulation | ||

| Douketis et al. 2015 (24) |

RCT (multicenter), 1813 patients, follow-up: 37 days postoperatively |

Reduction in postoperative risk of bleeding (RR: 0.4; 95% CI: [0.2; 0.8]) and no increase in thromboembolic events when “bridging” with LMWH was forgone in patients with atrial fibrillation. Evidence level: high |

“Bridging,” temporary bridging anticoagulation; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; RR, relative risk;

OR, odds ratio; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; POD, postoperative delirium; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial

Preoperative Phase

The importance of primary care physicians

Elderly patients benefit from a good preclinical work-up for their pending surgery. Optimally, this is initiated by the primary care physician and includes, e.g., compensating nutritional deficits, treatment of anemia, or optimizing long-term medication (box). By using the national medication plan, it is possible to avoid loss of information when switching medication from the outpatient to the inpatient sector. The primary care physician‘s knowledge of often pre-existing multimorbidity enables the potential specific benefits of surgical treatment to be weighed up against its disadvantages in advance and together with the patient. Moreover, the primary care physician‘s assessment of which drugs might need to be discontinued perioperatively or modified in terms of dose or the time at which they are taken is important.

BOX. Outpatient measures for the preoperative work-up of elderly patients.

-

Surgical work-up performed by the primary care physician

Exclude anemia, treat where necessary

Analyze and optimize medication, use the national medication plan

Exclude malnutrition, prescribe oral nutritional supplements if necessary

Determine cognitive status; document this for hospital admission

Evaluate fall risk; document this for hospital admission

Provide consultation regarding living will

Provide consultation regarding prehabilitation: fall prevention, breathing exercises

Preoperative assessment

The aim of the preoperative work-up in elderly patients is to reliably identify common risk constellations in old age (table 1) and reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications by means of preventive measures.

Table 1. Availability of German-language instruments for the preoperative assessment of elderly patients.

| Domain | Instrument | Availability |

| Frailty | e.g., Identification of Seniors at Risk e.g., LUCAS-Funktionsindex (for patients not dependent on care) |

German Society for Geriatrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geriatrie): www.dggeriatrie.de Netzwerk Gesund Aktiv: albertinen@netzwerk-gesundaktiv.de |

| Cognition | e.g., DemTect e.g., Mini-Cog e.g., IQ-CODE |

Competence Center for Geriatrics: www.kcgeriatrie.de Homepage of the POSE Study: pose-trial.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Mini-Cog-deutsch-für-POSE.pdf via Australian National University: http://rsph.anu.edu.au/research/tools-resources/informant-questionnaire-cognitive-decline-elderly |

| Malnutrition | NRS-SF (in- and outpatients) NRS2000 (inpatients) |

www.mna-elderly.com oder www.dgem.de/screening |

| Inappropriate medication in old age | PRISCUS list | www.priscus.net |

Risk: frailty and poor functional status

Frailty in elderly patients represents the most important predictor of the postoperative course (odds ratios [OR]: 2.6–11) (2, 3, e5– e11). Frailty is associated with the concomitant onset of a number of age-related functional impairments that make older patients more susceptible to postoperative complications (e12). A preoperative assessment should be performed to determine functional status (4, 5). In the case of high-risk patients, multimodal prehabilitation with physical training and oral nutritional supplements should be considered (6– 8). Prehabilitation programs are currently being evaluated (e13). Calling in a geriatric specialist permits not only a more extensive assessment, but also enables prehabilitation measures to be carried out in a geriatric treatment unit.

Risk: chronic disorders and comorbidity

The prevalence of in particular cardiac, vascular, pulmonary, as well as metabolic and cerebral diseases is higher in old age (9, e14– e16). A guideline-compliant preoperative evaluation is able to identify these disorders, which can be further investigated by means of additional diagnostic methods (10).

Risk: pre-existing cognitive impairment

Pre-existing cognitive impairment is an important predictive factor for the development of POD (OR: 2.5; 95% confidence interval: [1.5; 4.2], OR: 4.5 [1.9; 13], OR: 4.3 [2.2; 8.5]) (11, e17, e18). Therefore, the elderly patient‘s preoperative baseline cognitive status is of particular importance. Since only around 50% of dementia patients are ever medically diagnosed as such (e19), one can assume that the real number of cases is higher. Therefore, a preoperative evaluation of cognitive function is essential (5, 12, e20). DemTect (dementia detection) and Mini-Cog (short cognitive test) are suitable instruments to this end (13, e21). There is also the IQ-CODE (Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly), which is an assessment questionnaire that can be completed by relatives or carers.

Risk: osteoporosis and fall risk

Falls are a significant health risk in old age. Approximately 35% of 65- to 90-year-olds fall once a year and 10% more than once a year (e22). Falls result in fractures and fear of falling, as well as loss of quality of life and independence. The risk of falling increases in high-risk patients following surgery, e.g., due to frailty, reduced muscle strength, and reduced mobility. A risk assessment should be carried out preoperatively. Individual or group preventive exercise programs aimed at functional improvement as part of prehabilitation can also effectively reduce fall risk (14, e23). This needs to be flanked perioperatively by guideline-compliant diagnosis and treatment of concomitant osteoporosis, particularly following a fracture (15).

Risk: malnutrition

Malnutrition is a frequent problem often overlooked in the surgical field. Its prevalence among elderly patients is between 45% and 55% (e24, e25). Malnutrition is an unfavorable prognostic factor for the perioperative course and associated with an increased rate of complications and delirium (e26). Therefore, elderly patients should be examined preoperatively for malnutrition (5). The MNA-SF (Mini Nutritional Assessment) or the NRS2000 (Nutritional Risk Screening) are suitable tools to this end (16, e27). In line with the guidelines of the German Society for Nutritional Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährungsmedizin, DG), malnourished patients in particular should be encouraged to use oral nutritional supplements (17, 18).

Risk: polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is a relevant risk factor in elderly patients and associated with a poor postoperative outcome (e28, e29). Non-essential drugs, including non-prescription preparations, should be discontinued during the perioperative phase. A critical evaluation of potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) in the elderly, e.g., using the PRISCUS list, is most particularly recommended in the perioperative phase (5, 19, 20– 22). In general, long-term cardiac medications should be continued in order to avoid rebound phenomena (e.g., tachycardia upon discontinuation of ß-receptor blockers) (e30). The same applies to pain medication: preoperatively administered opioids should also be continued in the perioperative setting.

Risk: anticoagulation

Between 33%–43% of all elderly patients use long-term anticoagulants (e31). The use of anticoagulants in the elderly is essentially the same as in younger patients; however, the reduced renal function frequently seen in old age needs to be borne in mind. Important parameters for the perioperative use of novel oral anticoagulants (NOAC, non-vitamin-K-dependent oral anticoagulants) include kidney and liver function, co-medication, the time at which the drug was last used, the size and urgency of the procedure, as well as the risk of intraoperative bleeding (e.g., HAS-BLED score >3) (23, e32, e33). In the majority of cases, perioperative bridging anticoagulation is no longer recommended when using NOAC and vitamin-K-antagonists (24, e34). This recommendation does not apply to patients at high risk for thromboembolism (e.g., due to mechanical heart valve replacement, coagulation disorders, CHA2DS2-VASC score >5) (25).

Perioperative pain concept

A detailed pain history should be taken preoperatively. Presenting the patient with the pain scale to be used postoperatively (e.g., the numerical rating scale [NRS]) as early on as in the preoperative setting, as well as discussing in detail the likely postoperative analgesic concept and the use of analgesics preoperatively, is recommended.

Opioids, if unavoidable, should be administered at a reduced initial dose according to the WHO analgesic ladder. Although they have a largely non-toxic effect on organs and are effective in the elderly, they do have disadvantages in older patients, i.e., exacerbated and hazardous side effects (e.g., development of delirium, increased fall risk) and can interact with other drugs metabolized via cytochrome P450. If possible, a non-opioid should be additionally administered in order to avoid or reduce the use of opioids. The selection of a non-opioid should be made on the basis of pre-existing disorders, with paracetamol and metamizole having the more favorable benefit–risk profile in the elderly (e35) (e35).

Intraoperative phase

The time immediately prior to surgery, the induction and maintenance of anesthesia, the surgical procedure, and the early postoperative phase are all important determinants of the postoperative course. Designing a procedure that promotes the patient‘s well-being and sense of orientation in the operating room represents an evidence-based, medically indicated measure for the prevention of delirium (12, 26, 27).

Preoperative fasting

Dehydration is less well-tolerated in advancing age. Excessive preoperative fasting increases discomfort and agitation and promotes the onset of POD (28). A fasting period of 6 h is adequate in terms of the prevention of aspiration (29). Clear fluids should not be avoided for longer than 2 h preoperatively, since these are not associated with an increased risk of aspiration or other complications (30). The preoperative consumption of carbohydrate-containing drinks up to 2 h prior to surgery is beneficial and, as a form of non-drug-based anxiolysis, has a positive effect on the well-being of the patient (31).

Intraoperative medication

The altered pharmacokinetics and dynamics seen in old age also affect anesthesia. Sedated older patients should always undergo neuromonitoring, since excessively deep anesthesia increases the risk for postoperative cognitive deficits and delirium (12). If muscle relaxants are to be used, short-acting substances should be selected where possible; metabolism that is independent of liver and kidney function is beneficial (e.g., cis-atracurium). Relaxometry should be performed concomitantly.

The duration of benzodiazepine action increases in a strongly age-dependent manner; furthermore, these substances are associated with the development of POD (32). Therefore, benzodiazepines should be used with the utmost restraint in elderly patients. In the case of active benzodiazepine abuse, which applies to no small number of elderly patients (prevalence of around 1.2 million) (e36), abrupt discontinuation in the perioperative phase is naturally not recommended.

Opioids as well as postoperative pain increase the risk of POD (opioids: OR: 2.5 [1.2; 5.2], pain: OR: 3.7 [1.5; 8.9]) (32, e37). Therefore, adequate opioid-reduced analgesia is of great importance. Regional anesthesia techniques are recommended if the intervention and the condition of the patient permit. The patient‘s sensory orientation (hearing and visual aids), direct verbal communication, and non-pharmacological sedation also play an important role in the operating room in terms of delirium prevention.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis

There are no significant differences between perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis (PAP) in the elderly and that in younger patients, either in terms of indication or performance. Particularly due to frequent polypharmacy, antibiotics that have a low interaction potential and which are well-tolerated are to be preferred. Beta-lactam antibiotics, in particular group 1 and 2 cephalosporins, are preferable. Elderly patients have an increased risk for multi-resistant pathogens (MRP), due to repeated hospital stays or antibiotic treatment in the preceding 3 months. In the case of confirmed MRP colonization, an adjustment of PAP should be considered depending on the individual case; however, this is generally not necessary. It may be beneficial if the resistant pathogen is found in the operating area, e.g., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization of the skin. An attempt at preoperative decolonization is helpful in such cases. This applies all the more so if cardiac, neurosurgical, vascular, or orthopedic interventions are planned (e38).

Surgical procedure

Particularly in the case of elderly patients, the surgical indication should not be made solely on the basis of the question “What is surgically and technically feasible?,” but much more so on the question of “What makes sense?” (33). One should take into account here that the immediate complication and mortality rates in the early postoperative course, as well as the 1-year mortality rate following visceral surgery, are higher among patients above the age of 80 years compared to younger patients (1-year mortality: between 4.8% and 32%, depending on the type of intervention) (34, 35, e39). Therefore, the question arises as to whether a surgical approach is in actual fact associated with a better outcome for the patient compared to conservative treatment.

The adherence in trauma surgery to implementing postoperatively desired partial weight-bearing should be critically assessed preoperatively. In the case of restricted adherence, greater importance should be attributed to restoring immediate full weight-bearing than to achieving unrestricted limb mobility in the further course. The aim is to achieve definitive treatment with one single surgical procedure (e40).

Last but not least, since soft tissue management also poses a challenge, minimally invasive procedures should be considered. Ideally, individual parameters are assessed at an interdisciplinary level and across all professional groups, thereby preventing a complication-prone, one-dimensional decision-making process based on the surgical diagnosis.

Postoperative phase

Delirium screening and nursing aspects

As part of the identification of delirium, it is important to recognize early changes in the patient‘s awareness in order to initiate further measures. The nursing staff plays a crucial role here. Therefore, it is essential that carers are aware of the risk factors for POD and are trained in the implementation of preventive measures.

There are a number of validated assessment instruments for delirium screening in intensive care units and recovery rooms that have already been tried and tested in clinical routine, e.g.:

CAM-ICU (Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit)

ICDSC (Intensive Care Screening Checklist).

There are also observation scales for wards, such as (e41– e45):

DOS (Delirium Observation Screening Scale)

Nu-Desc (Nursing Delirium Screening Scale)

Four-Item Assessment Test (4AT).

Delirium screening should begin in the early postoperative phase and continue up to the fifth postoperative day (12).

Age-appropriate care in inpatient routine

Delirium prevention is of the utmost importance in the nursing care of elderly hospital patients. It has been shown that the risk of delirium can be reduced by 30%–50% as a result of preventive measures alone (1, 36, e41, e46– e48). Non-pharmacological interventions focus, for instance, on the following areas (37):

Orientation

Stimulation and communication

Mobilization

Regulating the sleep–wake rhythm

Involving relatives and persons of trust.

Fall prevention measures, as well as monitoring and checking actual food intake by means of dietary and fluid logs, are just as important in elderly patients as adequate pain management (e37).

Postoperative resumption of normal diet

It is generally not necessary to interrupt food intake in the postoperative phase (38). An early normal oral or enteral diet reduces the risk of infection and has a positive impact on the length of hospital stay. Since elderly patients in particular often have reduced sensations of hunger and thirst, they should be encouraged to drink sufficient quantities. The daily fluid intake of all elderly patients should be known and documented in order to promptly counteract dehydration (17, 38). Patients at high nutritional risk (body mass index <22 kg/m2) in whom adequate oral food intake cannot be achieved even with nursing support should receive prompt enteral supplements, combined with parenteral supplements where necessary (17, 18, 38, 39).

Hospital discharge

More attention should be paid to the above-mentioned aspects as part of discharge management in order to plan optimal post-inpatient care for the patient together with their primary care physician. Early rehabilitation under specialist geriatric care and aimed at restoring the patient‘s ability for self-help, as well as functional autonomy in everyday life, should be planned in good time if required.

Summary

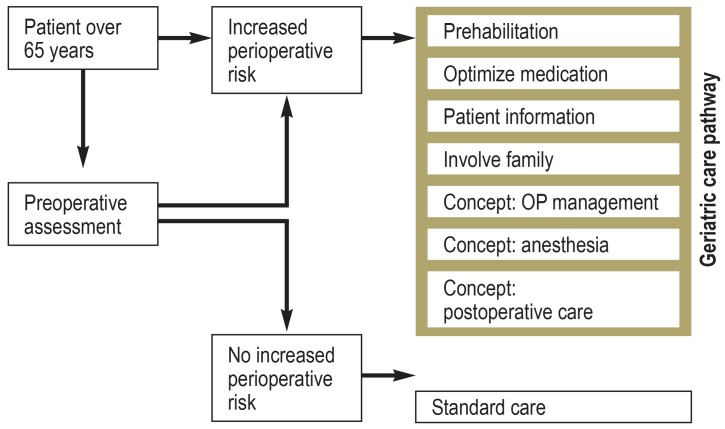

Good perioperative care of elderly patients can only be achieved if there is an interdisciplinary consensus on treatment planning and goal setting. In terms of the treatment goal, preserving the functional status of the patient should be given equal priority to treating the underlying disease. The cornerstones of this include the identification of individual age-specific risk factors and the prompt initiation of appropriate preventive measures. The preoperative work-up (whether in the in- or outpatient setting), surgical and anesthesia planning, the postoperative inpatient phase, as well as transfer to further outpatient care should be structured with these aspects in mind (Table 2, Figure). To this end, an interdisciplinary and cross-professional concept for the perioperative care of elderly patients needs to be developed. Improved collaboration between the in- and outpatient sectors is essential here, because only when all treating physicians and therapists know and implement this concept can the optimal benefit be conferred to the patient.

Table 2. Perioperative measures in the care of elderly patients.

| Measure | Target group |

| Preoperative | |

| Screening for malnutrition | All patients ≥ 65 years |

| Evaluation of cognitive function | |

| Screening for frailty | |

| Fall-risk evaluation | |

| Medication analysis for potentially inappropriate medication | |

| Carbohydrate-containing drinks the evening before and 2 h prior to surgery | |

| Breathing exercises to prevent pneumonia | |

| Oral nutritional supplements | Malnourished or frail patients |

| Optimize medication perioperatively | Patients on potentially inappropriate medication |

| Initiate fall prevention | Patients at high risk for falls |

| Patient information on delirium and delirium prevention (patient participation) | High-risk patients ≥ 65 years |

| Keep preoperative fasting times as short as possible | |

| Exclude anemia and treat where necessary | |

| Prehabilitation (physical activity) | |

| Involve family in targeted manner | |

| Intraoperative | |

| Avoid benzodiazepines (except in the case of severe anxiety) | All patients ≥ 65 years |

| Keep hearing aids, glasses, and dentures available in the operating room | |

| Particularly age-appropriate surgical concept | High-risk patients ≥ 65 years |

| Particularly age-appropriate anesthesia: prewarming, relaxometry, age-appropriate medication | |

| Postoperative | |

| Delirium screening in the recovery room and on the ward up to postoperative day 5 | All patients ≥ 65 years |

| Monitor oral food intake, supplement if necessary | Patients at risk for malnutrition |

| Delirium prevention measures on the ward: facilitate orientation, regulated sleep–wake rhythm, early mobilization, early removal of catheters and cannulas, family involvement | High-risk patients ≥ 65 years |

| Fluid and food management on the ward | |

Although it would be desirable to implement numerous measures for all elderly patients, this will generally not be possible due to time, personnel, and financial resources. In such cases, the authors recommend their implementation at least in patients at high perioperative risk. This group includes elderly patients with frailty, cognitive impairment, or severe multimorbidty.

Figure.

Pragmatic approach to the perioperative care of elderly patients

Key messages.

Elderly people represent a particularly vulnerable patient group at higher perioperative risk and, as such, require treatment concepts that are specially tailored to these risks.

These treatment concepts should include an extensive preoperative assessment, a structured intraoperative procedure, and an equally structured postoperative inpatient treatment pathway.

Since the primary care physician plays an important role in the preoperative work-up of the patient, collaboration between the in- and outpatient sectors needs to be further developed.

The optimal perioperative treatment of elderly patients requires close interdisciplinary and interprofessional collaboration.

Perioperative delirium prevention is an important therapeutic goal in the treatment of elderly patients.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Schaefer-Tsorpatzidis.

Acknowledgments

An interdisciplinary and interprofessional alliance was formed on the initiative of the German committee on geriatric anesthesia of the German Society for Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin, DGAI). An expert consensus on the essential principles of the perioperative care of the elderly patient was met in collaboration with the appointed representatives of the German societies for general and family medicine, general and visceral surgery, nutritional medicine, geriatrics, trauma surgery, as well as specialist nursing and other healthcare professions. The following colleagues made a crucial contribution to the manuscript: Prof. Dr. Berthold Bein (DGAI), Dr. Simone Gurlit (DGAI), Prof. Dr. Hans Jürgen Heppner (DGG), Dr. Stephanie Schibur (GDU), Inke Zastrow, Prof. Dr. Ulrich Liener (DGU), Prof. Dr. Esther Pogatzki-Zahn (DGAI), Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Koppert (DGAI), Dr. Beatrice Grabein, and Henning Bolle (DGF). Our heartfelt thanks also go to Prof. Dr. A. E. Goetz and Dr. A.-K. Riegel for their supervision and critical review of the manuscript, as well as to the Johanna und Fritz Buch Gedächtnis-Stiftung

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

Prof. Weimann received lecture fees as well as travel cost reimbursement from Baxter, Berlin Chemie, B. Braun/Melsungen, Ethicon, Fresenius, Kabi, Lilly, Medtronic, Nestlé, and Nutricia. He received trial support (third-party funding) from Baxter.

The remaining authors state that they have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Coch Data Syst Rev. 2016;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3. Cd005563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0329-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt J, Tricco AC, Talbot-Hamon C, et al. Identifying older adults at risk of harm following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2018;16 doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0986-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkelbach O, Morgeli R, Balzer F, et al. [Why and How Should I Assess Frailty? A guide for the preoperative anesthesia clinic] AINS. 2017;52:765–776. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-104682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Hert S, Staender S, Fritsch G, et al. Pre-operative evaluation of adults undergoing elective noncardiac surgery: updated guideline from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. EJA. 2018;35:407–465. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Roca J, et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267:50–56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valkenet K, van de Port IG, Dronkers JJ, de Vries WR, Lindeman E, Backx FJ. The effects of preoperative exercise therapy on postoperative outcome: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25:99–111. doi: 10.1177/0269215510380830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillis C, Buhler K, Bresee L, et al. Effects of nutritional prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:391–410e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistisches Bundesamt, editor. Gesundheit im Alter, 2012. www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Gesundheitszustand/GesundheitimAlter0120006109004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed on 8 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin (DGAI), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin (DGIM), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie (DGCH), Zwissler B. Präoperative Evaluation erwachsener Patienten vor elektiven, nicht herz-thoraxchirurgischen Eingriffen. Gemeinsame Empfehlung der DGAI, DGCH und DGIM. Anästh Intensivmed. 2017;58:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sprung J, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, et al. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients is associated with subsequent cognitive impairment. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:316–323. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldecoa C, Bettelli G, Bilotta F, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology evidence-based and consensus-based guideline on postoperative delirium. EJA. 2017;34:192–214. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalbe E, Kessler J, Calabrese P, et al. DemTect: a new, sensitive cognitive screening test to support the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and early dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:136–143. doi: 10.1002/gps.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwan E, Straus SE. Assessment and management of falls in older people. CMAJ. 2014;186:E610–E621. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osteologie D. Leitlinie Osteoporose. www.dv-osteologie.org/uploads/Leitlinie%202017/Finale%20Version%20Leitlinie%20Osteoporose%202017_end.pdf (last accessed on 8 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:782–788. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volkert DBJ, Frühwald T, Gehrke I, et al. Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ernährungsmedizin (DGEM) in Zusammenarbeit mit der GESKES, der AKE und der DGG: Klinische Ernährung in der Geriatrie. Aktuel Ernahrungsmed. 2013;38:e1, e48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2018:1–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thurmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:543–551. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Geriatrics Society. Updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohanty S, Rosenthal RA, Russell MM, et al. Optimal perioperative management of the geriatric patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:930–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, Ko CY, Esnaola NF. Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093–1100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823–833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denkinger MK, Grünewald M, Kiefmann R. Antikoagulation bei alterstraumatologischen Patienten Weissbuch Alterstraumatologie: Antikoagulation und Thromboseprophylaxe. OUP. In: Liener UC, Becker C, Rapp K, editors. Dienst am Buch Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH. 1. Stuttgart: 2018. pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Peri-operative care of the elderly 2014. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:81–98. doi: 10.1111/anae.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohanty S, Rosenthal R, Russell M, Neuman M, Ko C, Esnaola N. Optimal perioperative management of the geriatric patient: a best practices guideline. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:930–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radtke FM, Franck M, MacGuill M, et al. Duration of fluid fasting and choice of analgesic are modifiable factors for early postoperative delirium. EJA. 2010;27:411–416. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283335cee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin e. V. und Berufsverband Deutscher Anästhesisten e. V. Entschließungen, Empfehlungen, Vereinbarungen. Ebelsbach: Aktiv Druck & Verlag GmbH. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MD, McCall J, Plank L, Herbison GP, Soop M, Nygren J. Preoperative carbohydrate treatment for enhancing recovery after elective surgery. Coch Data Syst Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009161.pub2. CD009161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amer MA, Smith MD, Herbison GP, Plank LD, McCall JL. Network meta-analysis of the effect of preoperative carbohydrate loading on recovery after elective surgery. Br J Surg. 2017;104:187–197. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40:23–29. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loh A, Simon D, Kriston L, Härter M. [Shared decision making in medicine] Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2007;104 (21 A):1483–1488. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surgery. 2016;151:538–545. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuld J, Glanemann M. Chirurgische Therapie des kolorektalen Karzinoms im Alter. Chirurg. 2017;88:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s00104-016-0342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CC, Li HC, Liang JT, et al. Effect of a modified hospital elder life program on delirium and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surgery. 2017;152:827–834. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Delirium: prevention, diagnosis and management. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103 (last accessed on 8 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weimann A, Breitenstein S, Breuer JP, et al. S3-Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ernährungsmedizin (DGEM) in Zusammenarbeit mit der GESKES, der AKE, der DGCH, der DGAI und der DGAV: Klinische Ernährung in der Chirurgie. Aktuel Ernahrungsmed. 2013;38:e155–e197. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2017;36:623–650. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Statistisches Bundesamt. Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik). Operationen und Prozeduren der vollstationären Patientinnen und Patienten in Krankenhäusern. Wiesbaden. Statistisches Bundesamt. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E2.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:210–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Anastasiadis K, Argiriadou H, Kosmidis MH, et al. Neurocognitive outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery using minimal versus conventional extracorporeal circulation: a randomised controlled pilot study. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2011;97:1082–1088. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.218610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1578–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Neuman HB, Weiss JM, Leverson G, et al. Predictors of short-term postoperative survival after elective colectomy in colon cancer patients = 80 years of age. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1427–1435. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2721-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Covinsky KE, Justice AC, Rosenthal GE, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS. Measuring prognosis and case mix in hospitalized elders The importance of functional status. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:203–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Davis RB, Iezzoni LI, Phillips RS, Reiley P, Coffman GA, Safran C. Predicting in-hospital mortality The importance of functional status information. Med Care. 1995;33:906–921. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Buigues C, Juarros-Folgado P, Fernandez-Garrido J, Navarro-Martinez R, Cauli O. Frailty syndrome and pre-operative risk evaluation: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Shem Tov L, Matot I. Frailty and anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30:409–417. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Schmidt M, Eckardt R, Altmeppen S, Wernecke KD, Spies C. Functional impairment prior to major non-cardiac surgery is associated with mortality within one year in elderly patients with gastrointestinal, gynaecological and urogenital cancer: a prospective observational cohort study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Oakland K, Nadler R, Cresswell L, Jackson D, Coughlin PA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between frailty and outcome in surgical patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:80–85. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwee D, et al. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:1163.e1–1163e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.McIsaac DI, Saunders C, Hladkowicz E, et al. PREHAB study: a protocol for a prospective randomised clinical trial of exercise therapy for people living with frailty having cancer surgery. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022057. e022057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Steppuhn H KR. Scheidt-Nave C 12-Monats-Prävalenz der bekannten chronisch obstruktiven Lungenerkrankung (COPD) in Deutschland. Journal of Health Monitoring. 2017;2:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- E15.Heidemann C, Kuhnert R, Born S, et al. 12-Monats-Prävalenz des bekannten Diabetes mellitus in Deutschland. Journal of Health Monitoring. 2017;2:48–56. doi: 10.17886/RKI-GBE-2017-017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Busch MA, Schienkiewitz A, Nowossadeck E, Gosswald A. [Prevalence of stroke in adults aged 40 to 79 years in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)] Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz) 2013;56:656–660. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Fong TG, Davis D, Growdon ME, Albuquerque A, Inouye SK. The interface between delirium and dementia in elderly adults. Lancet Neurology. 2015;14:823–832. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00101-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43:326–333. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Engels D, Pfeuffer F, Heusinger J, et al. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen selbständiger Lebensführung in stationären Einrichtungen (MuG IV) - Demenz, Angehörige und Freiwillige, Versorgungssituation sowie Beispielen für „Good Practice“ In: Bundesministerium für Familie, Frauen und Jugend, (ed.): Integrierter Abschlussbericht 2007. www.bmfsfj.de/blob/78928/9465bec83edaf4027f25bb5433ea702e/abschlussbericht-mug4-data.pdf (last accessed on 15 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E20.von Renteln-Kruse W, Neumann L, Klugmann B, et al. Geriatric patients with cognitive impairment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:103–112. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The mini-cog: a cognitive ‚vital signs‘ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:1021–1027. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::aid-gps234>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Klenk J, Kerse N, Rapp K, et al. Physical activity and different concepts of fall Rrisk estimation in older people—results of the ActiFE-Ulm study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129098. e0129098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Siegrist M, Freiberger E, Geilhof B, et al. Fall prevention in a primary care setting. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:365–372. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Konturek PC, Herrmann HJ, Schink K, Neurath MF, Zopf Y. Malnutrition in hospitals: it was, is now, and must not remain a problem! Sci Monit. 2015;21:2969–2975. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Pirlich M, Schutz T, Norman K, et al. The German hospital malnutrition study. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2006;25:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Phillips P. Grip strength, mental performance and nutritional status as indicators of mortality risk among female geriatric patients. Age Ageing. 1986;15:53–56. doi: 10.1093/ageing/15.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2003;22:321–336. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(02)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Harstedt M, Rogmark C, Sutton R, Melander O, Fedorowski A. Polypharmacy and adverse outcomes after hip fracture surgery. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;11 doi: 10.1186/s13018-016-0486-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Kennedy JM, van Rij AM, Spears GF, Pettigrew RA, Tucker IG. Polypharmacy in a general surgical unit and consequences of drug withdrawal. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:353–362. doi: 10.1046/1365-2125.2000.00145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Barnett SR. Polypharmacy and perioperative medications in the elderly. Anesthesiol Clin. 2009;27:377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Madsen CM, Jantzen C, Lauritzen JB, Abrahamsen B, Jorgensen HL. Temporal trends in the use of antithrombotics at admission. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:368–373. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2016.1195662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Oprea AD, Noto CJ, Halaszynski TM. Risk stratification, perioperative and periprocedural management of the patient receiving anticoagulant therapy. J Clin Anesth. 2016;34:586–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Lip GY, Frison L, Halperin JL, Lane DA. Comparative validation of a novel risk score for predicting bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation: the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Douketis JD, Healey JS, Brueckmann M, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation during dabigatran or warfarin interruption among patients who had an elective surgery or procedure. Substudy of the RE-LY trial. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:625–632. doi: 10.1160/TH14-04-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Meyer-Frießem C, Pogatzki-Zahn E. Postoperative Schmerztherapie Praxis der Anästhesiologie: konkret - kompakt - leitlinienorientiert. In: Wilhelm W, editor. Springer. Berlin: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- E36.Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen e. V. DHS Jahrbuch Sucht. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- E37.Vaurio LE, Sands LP, Wang Y, Mullen EA, Leung JM. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1267–1273. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000199156.59226.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) A national clinical guideline 2008, updated 2014. www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign104.pdf (last accessed on 8 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E39.Olufajo OA, Reznor G, Lipsitz SR, et al. Preoperative assessment of surgical risk: creation of a scoring tool to estimate 1-year mortality after emergency abdominal surgery in the elderly patient. Am J Surg. 2017;213:771–777e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Werther SFJ, Mayr E. Interdisziplinäres Management im Zentrum für geriatrische Traumatologie. Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie up2date. 2014;9:387–406. [Google Scholar]

- E41.Boettger S, Nunez DG, Meyer R, et al. Delirium in the intensive care setting: A reevaluation of the validity of the CAM-ICU and ICDSC versus the DSM-IV-TR in determining a diagnosis of delirium as part of the daily clinical routine. Palliat Support Care. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516001176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Gavinski K, Carnahan R, Weckmann M. Validation of the delirium observation screening scale in a hospitalized older population. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:494–497. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Hargrave A, Bastiaens J, Bourgeois JA, et al. Validation of a nurse-based delirium-screening tool for hospitalized patients. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Adamis D, Sharma N, Whelan PJ, Macdonald AJ. Delirium scales: a review of current evidence. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:543–555. doi: 10.1080/13607860903421011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, Straus SE. Does this patient have delirium? Value of bedside instruments. JAMA. 2010;304:779–786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Faught DD. Delirium: The nurse‘s role in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Medsurg Nurs. 2014;23:301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Kratz T, Heinrich M, Schlauss E, Diefenbacher A. Preventing postoperative delirium. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:289–296. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Olotu C. Eckart J, Jaeger K, Möllhof T, editors. Anästhesiologische Behandlungspfade für ältere Patienten Kompendium Anästhesiologie. Landsberg am Lech. Ecomed-Storck. 2018:1–14. 60.Erg.-Lfg. 11/18. [Google Scholar]