ABSTRACT

Purpose: To determine the prevalence of trachoma and water and sanitation coverage in four local government areas (LGAs) of Jigawa State, Nigeria: Birnin Kudu, Buji, Dutse and Kiyawa.

Methodology: A population-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in each LGA using Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) protocols. From each LGA, 25 villages were selected using probability-proportional-to-population size sampling; in each village, 25 households were selected using the random walk technique. All residents aged ≥1 year in selected households were examined by GTMP-certified graders for trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) and trichiasis, defined according to the WHO simplified trachoma grading scheme definitions. Water, sanitation and hygiene data were also collected through questioning and direct observation.

Results: In 2458 households of four LGAs, 10,669 residents were enumerated. A total of 9779 people (92% of residents) were examined, with slightly more females examined (5012; 51%) than men. In children aged 1–9 years, the age-adjusted prevalence of TF ranged from 5.1% (95% CI 2.5–9.0%) in Birnin Kudu to 12.8% (95% CI 7.6–19.4%) in Kiyawa, while the age- and gender-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in persons aged ≥15 years ranged from 1.9% (95% CI 1.4–2.5%) in Birnin Kudu to 3.1% (95% CI 2.2–4.0) in Dutse. Access to improved water sources was above 80% in all LGAs surveyed but access to improved sanitation facilities was low, ranging from 23% in Buji to 50% in Kiyawa.

Conclusion: Trachoma is a public health problem in all four LGAs surveyed. The full SAFE strategy needs to be implemented to achieve trachoma elimination.

KEYWORDS: Global Trachoma Mapping Project, prevalence, sanitation, trachoma, Trichiasis, water

Introduction

Trachoma is a disease caused by repeated infection of the conjunctival epithelium by particular strains of the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis;1,2 it is the principal cause of blindness of infectious origin worldwide.3 The main reservoir of the infection is in young children,4 in whom the clinical sign of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF), a feature of prolonged C. trachomatis-induced conjunctival inflammation, is often found.5 Frequent repeated infection and inflammation of the conjunctivae,6,7 can lead to conjunctival scarring, with resultant in-turning of the eyelashes. In-turned eyelashes that touch the eyeball (trichiasis)5 may damage the cornea, resulting in irreversible visual impairment or blindness.

An estimated 171 million people are at risk of the disease in Africa.8 In Nigeria, various surveys have shown trachoma to be of public health significance in many local government areas (LGAs, the equivalent of “districts” elsewhere).9–14 To implement the SAFE (Surgery for trichiasis, Antibiotics to clear infection, and promotion of Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement to reduce transmission) strategy, which is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the elimination of trachoma,15 district-level data on the prevalence of TF in 1–9 year-olds and trichiasis in persons aged ≥15 years are required. These data help programme managers determine which elements of the strategy to implement.16

Jigawa State is located in northern Nigeria and surrounded by states where trachoma has been found to be a public health problem.9,14,17 A 2007 state-level survey also documented trachoma to be a public health problem in Jigawa State itself; although this work did not generate the LGA-level prevalence indicators generally recommended to guide programme implementation,18 it was used as the basis to initiate SAFE strategy rollout19 for a number of LGAs. In 2013, the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP)20 supported the collection of LGA-level data in four LGAs of Jigawa where elimination activities had not yet commenced.

Methods

Sample size calculation

Each LGA was considered its own evaluation unit, with a separate population-based prevalence survey being conducted in each one, according to the same principles. Details of the sample size calculation have been reported elsewhere.21 Briefly, each survey attempted to include enough households to ensure that 1019 children aged 1–9 years would be present and consent to participate, because this would provide sufficient power to estimate an expected TF prevalence in 1–9-year olds of 10% with an absolute precision of 3%, assuming a design effect of 2.65.

Team training

Each field team consisted of a grader and a recorder. These personnel were trained and certified according to the standard operating procedures of the GTMP.21 Version 1 of the GTMP training system22 was used. Grader trainees were required to pass a slide-based test of diagnostic accuracy after which they were eligible to attempt live subject-based inter-grader assessment tests to prove themselves survey-ready, while recorder trainees were required to pass an examination testing their data capture accuracy, as described previously.21

Household selection

In each LGA, 25 villages were selected using a systematic, probability-proportional-to-population-size methodology.16 In selected villages, 25 households were selected. Despite the limitations of the random walk method,23–25 it was used to select households as the security situation at that time was volatile and survey coordinators felt it was better to use a method with which communities were familiar.

Data collection

Members of selected households aged ≥1 year were eligible to be included. With the aid of ×2.5 magnifying loupes, graders examined the eyes of all consenting participants for the signs of trichiasis, TF and trachomatous inflammation – intense (TI), according to the criteria of the WHO simplified grading system.5 Collection of data on household-level sources of water and the type of sanitation facility was integrated into the survey, through interviews with household members plus direct observation. All data were entered into the LINKS-GTMP app running on Android smartphones, which automatically collected global positioning system (GPS) coordinates for each household.21 Once phones were within range of a suitable network, data were uploaded to a secure cloud-based server.21,26

Data analysis

The Nigeria census for 200627 was used as the reference for data adjustment. The proportion of 1–9-year-olds with TF was adjusted at village level for age, in one year age bands. The proportion of adults with trichiasis was adjusted at village level for gender and age, in 5-year age bands. The means of the adjusted village-level proportions provided the LGA-level prevalences. Confidence intervals (CIs) were determined by bootstrapping adjusted village-level proportions, with replacement, over 10,000 replications.

Water sources and sanitation facilities were defined as “improved” using the criteria established by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program (JMP) for Water Supply and Sanitation, as reported up until 2015.28

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (NHREC/01/01/2007) and the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (reference 6319). Consent was obtained verbally, and documented electronically. For individuals below 15 years of age, consent was given by a parent or guardian. Persons with active trachoma were given a course of 1% topical tetracycline eye ointment, and those with trichiasis were referred to the nearest certified trichiasis surgeon.

Results

Residents enumerated from 2458 households across the four LGAs totalled 10,669. A total of 5,538 (52%) residents were female (Table 1). A total of 9779 people (92% of residents) were examined; 473 people (4%) were absent, while 447 people (4%) refused examination (Table 1). Of examined individuals, 5012 (51%) were female.

Table 1.

Number of 1–9-year olds and number of ≥15-year-olds resident, examined, absent and refused; prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF); and prevalence of trichiasis; by Local Government Area (LGA), Global Trachoma Mapping Project Jigawa State, Nigeria, June and July, 2013.

| LGA | Number of villages sampled | 1–9-year olds |

≥15-year-olds |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | Examined | Absent | Refused | TF prevalencea (95% CI) | Resident | Examined | Absent | Refused | Trichiasis prevalenceb (95% CI) | ||

| Birnin Kudu | 25 | 942 | 913 | 11 | 18 | 5.09 (2.5–9.0) | 1576 | 1458 | 99 | 19 | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) |

| Buji | 25 | 953 | 928 | 18 | 7 | 8.1 (4.8–11.5) | 1469 | 1344 | 72 | 53 | 2.1 (1.5–2.8) |

| Dutse | 25 | 892 | 867 | 8 | 17 | 8.1 (4.5–13.1) | 1534 | 1314 | 118 | 102 | 3.1 (2.2–4.0) |

| Kiyawa | 25 | 942 | 903 | 13 | 26 | 12.8 (7.6–19.4) | 1593 | 1319 | 141 | 133 | 2.8 (2.1–3.4) |

| Totals | 100 | 3727 | 3611 | 50 | 68 | N/A | 6172 | 5435 | 430 | 307 | N/A |

aAdjusted for age in 1–year age bands (see text).

bAdjusted for gender and age in 5–year age bands (see text).

CI: confidence interval; N/A: not applicable.

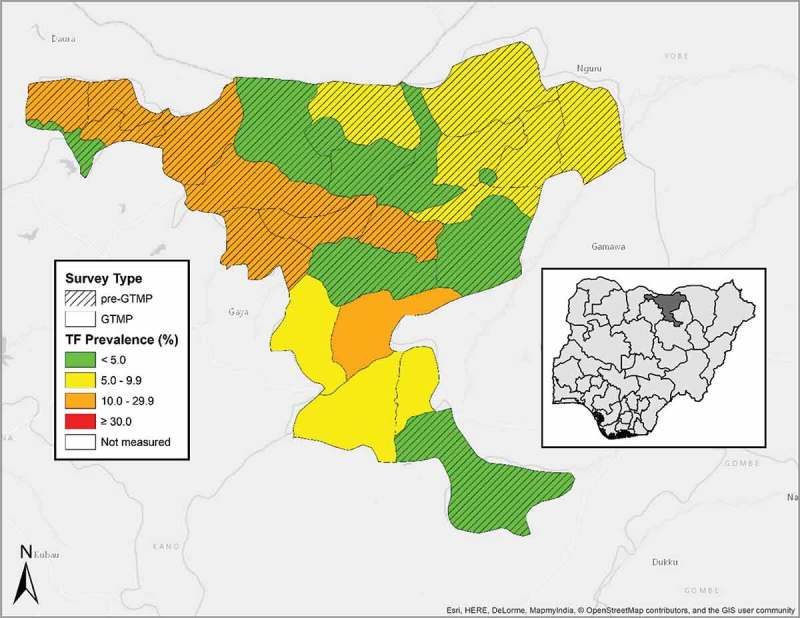

A total of 3,611 children aged 1–9 years were examined, of whom 1775 (49%) were female. The age-adjusted prevalence of TF in 1–9-year-olds ranged from 5.1% (95% CI 2.5–9.0%) in Birnin Kudu to 12.8% (95% CI 7.6–19.4%) in Kiyawa (Table 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Local Government Areas (LGAs) surveyed, and prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) in 1–9-year-olds, by LGA, Jigawa State, Nigeria, June and July, 2013. GTMP: Global Trachoma Mapping Project.

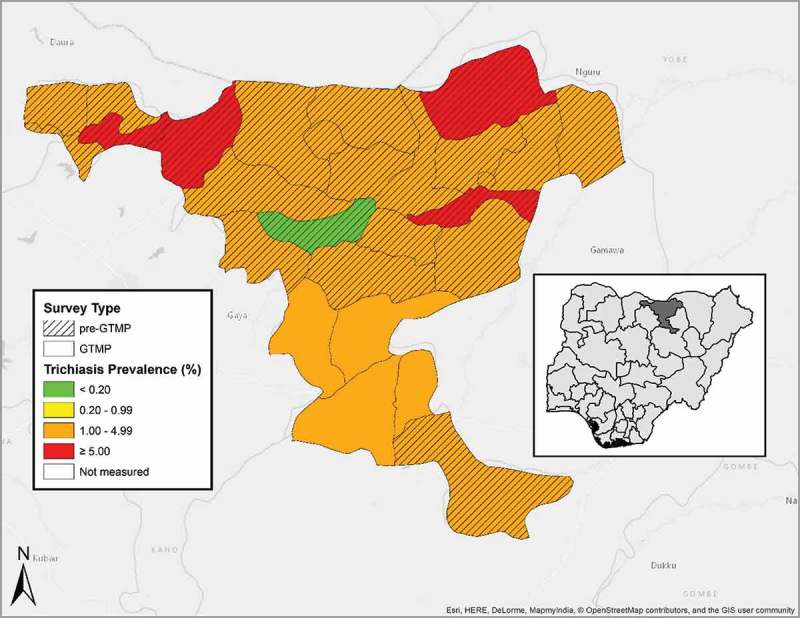

A total of 5,435 individuals aged ≥15 years were examined. Of those, 2,878 (53%) were female. The age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in ≥15-year-olds ranged between 1.9% (95% CI 1.4–2.5%) in Birnin Kudu and 3.1% (95% CI 2.2–4.0) in Dutse (Table 1 and Figure 2). The estimated backlog of trichiasis and the number of persons needing surgery to reach the elimination threshold in each LGA is shown in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of trichiasis in ≥15-year-olds, by LGA, Jigawa State, Nigeria, June and July, 2013. GTMP: Global Trachoma Mapping Project.

Table 3.

Local Government Area (LGA)-level estimates of the trichiasis backlog, Jigawa State, Nigeria. Global Trachoma Mapping Project, June and July 2013.

| Local Government Area | Number of ≥15-year-olds examined | Number of ≥15-year-olds with trichiasis | Prevalence of trichiasis in ≥15-year-olds, % (95% CI)a | Estimated total population aged ≥15 years | Estimated trichiasis backlog | Number of persons that need trichiasis management to achieve elimination threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birnin Kudu | 1458 | 67 | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | 175,900 | 3360 | 3046 |

| Buji | 1344 | 56 | 2.1 (1.5–2.8) | 54.479 | 1128 | 1.030 |

| Dutse | 1314 | 76 | 3.1 (2.2–4.0) | 140,635 | 4318 | 4.066 |

| Kiyawa | 1319 | 65 | 2.8 (2.1–3.4) | 96,853 | 2673 | 2500 |

| Total | 5435 | 264 | N/A | 413,442 | 11,479 | 10,643 |

In all four LGAs surveyed, over 80% of households had access to an improved source of water for face-washing within a 30 minute round trip (the equivalent of a < 1 km round trip). Household access to improved sanitation facilities ranged from 23.1% in Buji to 50.2% in Kiyawa (Table 2).

Table 2.

Household-level access to water and sanitation, by Local Government Area (LGA), Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Jigawa State, Nigeria, June and July, 2013.

| LGA | House-holds, n | Improved washing water, n (%) | Washing water source (improved or unimproved) <1 km, n (%) | Improved sanitation facilities, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birnin Kudu | 598 | 525 (87.8) | 517 (86.5) | 273 (45.7) |

| Buji | 623 | 546 (87.6) | 535 (85.9) | 144 (23.1) |

| Dutse | 619 | 548 (88.5) | 566 (91.4) | 165 (26.7) |

| Kiyawa | 618 | 602 (97.4) | 572 (92.6) | 310 (50.2) |

Discussion

In all four LGAs surveyed here, trachoma was a public health problem, as perhaps might have been predicted on the basis of 2007 state-level survey data.18 All LGAs surveyed require interventions for active trachoma, comprising antibiotic mass drug administration, promotion of facial cleanliness and environmental improvement.16 While Birnin Kudu, Buji and Dutse will require these interventions for at least one year, Kiyawa will require them for at least three years before impact surveys would be recommended.29 Considering the relatively high household-level water coverage (>80%) in all LGAs surveyed, in order to faithfully implement the SAFE strategy, emphasis should be placed on encouraging use of water for hygiene purposes, perhaps using established hygiene behaviour change techniques.30 Residents of these LGAs need to be able to relate the disease trachoma to poor personal hygiene so that water is used to ensure that faces are clean. . Success in this area might be anticipated, as the hardware is already available to implement the ‘F’ component of SAFE.

Availability of improved sanitation facilities was noted to be suboptimal. Though sanitation coverage was above the 2008 national average of 18%,31 there remains considerable room for improvement. Some studies associate latrine ownership with a lower risk of trachoma,32–34 and a recent model incorporating GTMP data from 13 countries, including Nigeria, found evidence of herd protection against TF for children living in communities in which sanitation coverage is >80%.35 To succeed in implementing the ‘E’ component of the SAFE strategy here, greater attention to providing the means for appropriate disposal of human faeces is recommended.

The trichiasis prevalence was above the elimination threshold in each LGA surveyed. In these four LGAs, an estimated 11,479 people have the potentially blinding stage of trachoma; if left untreated, this could progress in each person to cause corneal damage and irreversible visual impairment or blindness. There is therefore an urgent requirement to scale-up the surgery component of the SAFE strategy. A programme that provides surgery as close as possible to the residences of persons affected36 is needed to encourage all trichiasis patients to present for surgery; we note that in many places, women have lower access to trichiasis surgery services, are more afraid of surgery, and are less likely to have been offered surgery in the past.37 Thankfully, Jigawa State has already started training trichiasis surgeons to meet the predicted service requirements. In these four LGAs alone, a total of 10,643 trichiasis surgeries are likely to be needed to reach the elimination prevalence target. Training and certification of trichiasis surgeons will need to follow WHO recommendations.38 This will ensure that when surgeons are equipped and deployed, they provide high quality surgery to persons afflicted.

Trachoma is a public health problem in all four LGAs of Jigawa State surveyed in this series. There is a need to implement the full SAFE strategy in each of them, in order to move towards elimination of trachoma as a public health problem.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Ana Bakhtiari (2,9), Berhanu Bero (4), Sarah Bovill (8), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group

Funding Statement

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID; ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support health ministries to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number [AID-OAA-A-11-00048], and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow [098521] at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article.

References

- 1.Caldwell HD, Wood H, Crane D, et al. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiate between genital and ocular isolates. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(11):1757–1769. doi: 10.1172/JCI17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadfield J, Harris SR, Seth-Smith HMB, et al. Comprehensive global genome dynamics of Chlamydia trachomatis show ancient diversification followed by contemporary mixing and recent lineage expansion. Genome Res. 2017. doi: 10.1101/gr.212647.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2013;1(6):e339–49. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon AW, Holland MJ, Burton MJ, et al. Strategies for control of trachoma: observational study with quantitative PCR. Lancet. 2003;362(9379):198–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR.. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(4):477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West SK, Munoz B, Mkocha H, Hsieh YH, Lynch MC. Progression of active trachoma to scarring in a cohort of Tanzanian children. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8(2–3):137–144. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.2.137.4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolle MA, Muñoz BE, Mkocha H, West SK. Constant ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis predicts risk of scarring in children in Tanzania. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020: progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2014-2016. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92(26):359–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabiu MM, Abiose A. Magnitude of trachoma and barriers to uptake of lid surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8(2–3):181–190. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.2.181.4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jip NF, King JD, Diallo MO, et al. Blinding trachoma in Katsina state, Nigeria: population-based prevalence survey in ten local government areas. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(5):294–302. doi: 10.1080/09286580802256542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdull MM, Sivasubramaniam S, Murthy GV, et al. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(9):4114–4120. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King JD, Jip N, Jugu YS, et al. Mapping trachoma in Nasarawa and Plateau States, central Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(1):14–19. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.165282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JL, Sivasubramaniam S, Rabiu MM, Kyari F, Solomon AW, Gilbert C. Multilevel analysis of trachomatous trichiasis and corneal opacity in Nigeria: the role of environmental and climatic risk factors on the distribution of disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7):e0003826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mpyet C, Lass BD, Yahaya HB, Solomon AW. Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in Kano state, Nigeria. PloS One. 2012;7(7):e40421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Assembly Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma. 51st World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16 May 1998, Resolution WHA51.11. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, et al. Trachoma Control: a Guide for Program Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mpyet C, Ogoshi C, Goyol M. Prevalence of trachoma in Yobe State, north-eastern Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:303–307. doi: 10.1080/09286580802237633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramyil A, Wade P, Ogoshi C, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Jigawa State, north-western Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):184–189. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1037399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Report of the 3rd Global Scientific Meeting on TrachoMA, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19–20 July 2010 (WHO/PBD/2.10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon AW, Kurylo E. The global trachoma mapping project. Community Eye Health. 2014;27(85):18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):214–225. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project: Training for Mapping of Trachoma (Version 1) [Available at: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/node/357]. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brogan D, Flagg EW, Deming M, Waldman R. Increasing the accuracy of the Expanded Programme on Immunization’s cluster survey design. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:302–311. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner AG, Magnani RJ, Shuaib M. A not quite as quick but much cleaner alternative to the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) cluster survey design. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:198–203. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grais RF, Rose AMC, Guthmann J-P. Don’t spin the pen: two alternative methods for second-stage sampling in urban cluster surveys. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2007;4(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavluck A, Chu B, Mann Flueckiger R, Ottesen E. Electronic data capture tools for global health programs: evolution of LINKS, an Android-, web-based system. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(4):e2654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Population Commission 2006 Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: National and State Population and Housing Tables, Priority Tables (Volume 1). Abuja: National Population Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization, UNICEF Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water: 2015 Update and MDG Assessment. Geneva: UNICEF and World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organisation Meeting Report: Technical Consultation on Trachoma Surveillance. Decatur, USA. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delea MG, Solomon H, Solomon AW, Freeman MC. Interventions to maximize facial cleanliness and achieve environmental improvement for trachoma elimination: A review of the grey literature. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(1):e0006178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National population Commission 2008 National Demographic and Health Survey: Household Sanitation Facility Tables. Abuja: National Population Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oswald WE, Stewart AE, Kramer MR, et al. Active trachoma and community use of sanitation, Ethiopia. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(4):250–260. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.177758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courtright P, Sheppart J, Lane S, et al. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:322–325. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.6.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdou A, Nassirou B, Kadri B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for trachoma and ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Niger. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:13–17. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garn JV, Boisson S, Willis R, et al. Sanitation and water supply coverage thresholds associated with active trachoma: modeling cross-sectional data from 13 countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(1):e0006110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowman RJ, Soma OS, Alexander N, et al. Should trichiasis surgery be offered in the village? A community randomised trial of village vs. health centre-based surgery. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:528–533. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. Why Do People Not Attend for Treatment for Trachomatous Trichiasis in Ethiopia? A Study of Barriers to Surgery. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(8):e1766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello AB, et al. Trichiasis Surgery for Trachoma. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]