Abstract

Suicide attempt (SA) rates in the U.S. Army increased substantially during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. This study examined associations of family violence (FV) history with SA risk among soldiers. Using administrative data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS), we identified person-month records of active duty, Regular Army, enlisted soldiers with medically documented SAs from 2004–2009 (n=9,650) and a sample of control person-months (n=153,528). Logistic regression analyses examined associations of FV with SA, adjusting for socio-demographics, service-related characteristics, and prior mental health diagnosis. Odds of SA were higher in soldiers with a FV history and increased as the number of FV events increased. Soldiers experiencing past-month FV were almost five times as likely to attempt suicide as those with no FV history. Odds of SA were elevated for both perpetrators and those who were exclusively victims. Male perpetrators had higher odds of SA than male victims, whereas female perpetrators and female victims did not differ in SA risk. A discrete-time hazard function indicated that SA risk was highest in the initial months following the first FV event. FV is an important consideration in understanding risk of SA among soldiers.

Keywords: military, interpersonal violence, suicide, attempted, domestic violence, partner abuse, spouse abuse

1. Introduction

Rates of suicidal behaviors, including suicide deaths, attempts, and ideation, among U.S. Army soldiers increased considerably during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (Schoenbaum et al., 2014, Ursano et al., 2015a). Understanding factors that predict suicide attempts is important for risk detection and prevention. Previous research has examined risk as a function of socio-demographics and service-related characteristics, such as deployment history (Ursano et al., 2015a; Ursano et al., 2015b; Ursano et al., 2017). Little attention has been focused on the association of family violence with suicide attempts.

Family violence involves violent, aggressive, or abusive behaviors targeted towards spouses or partners and/or children. Most family violence studies focus on the recipients of assault or abuse (i.e., victimization). Family violence victimization increases the likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health disorders (Dutton et al., 2006; Marshall et al., 2005), which are risk factors for suicidal behavior in both active duty military personnel and veterans (Bachynski et al., 2007; Bossarte et al., 2012; Hyman et al., 2012; LeardMann et al., 2013). Family violence victimization has also demonstrated direct associations with suicidal behavior; however, previous studies frequently combined suicide-related outcomes of differing severity (e.g., ideation and attempts), making it difficult to determine the unique relationships of family violence to specific outcomes.

Family violence victimization was associated with greater risk of suicidal ideation in male and female active duty Air Force personnel (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2011) and a sample of veterans using Veterans Health Administration services (Cerulli et al., 2014). History of spousal abuse and sexual assault were associated with suicide attempts in active duty Canadian men and women (Belik et al., 2009). The association of family violence victimization with suicidal behavior is similarly observed among civilians (Devries et al., 2011; Gulliver and Fanslow, 2013). In a nationally representative sample of 5,238 U.S. adults (Simon et al., 2002), physical assault by a relative or intimate partner was more likely to be associated with suicidal ideation and behavior than assault by a stranger, suggesting that violence involving family members may be particularly devastating to victims.

Fewer studies have focused on family violence perpetrators. A number of small military and civilian studies, however, have indicated a relationship between family violence perpetration and suicidal ideation and behavior (Conner et al., 2001; Heru et al., 2006; Lucas et al., 2002; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2015). We are not aware of any studies that have examined how the relative effects of family violence victimization and perpetration can inform understanding of suicide risk. Further, although research has focused on the effects of family violence among male and female victims and perpetrators, there has been no systematic examination of how the association of family violence victimization and perpetration with suicide attempt may be influenced by gender.

This study examined the association of family violence with risk of suicide attempt among enlisted U.S. Army soldiers on active duty from 2004 through 2009 using administrative data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) (Ursano et al., 2014). Adjusting for basic socio-demographic and service-related variables, we examined the overall association of family violence with suicide attempt, as well as factors that have received little attention in previous studies, such as the number and recency of family violence events, and a soldier’s role as perpetrator or victim. We also examined whether the association of family violence with suicide attempt varied by gender, deployment status (never deployed, currently deployed, previously deployed), and time in service, which are associated with suicide attempts among soldiers (Ursano et al., 2015a; Ursano et al., 2015b; Ursano et al., 2017) and may play unique roles in modifying the effects of family violence. History of family violence may carry different risks based on phases of deployment, which may be particularly salient for those who have been exposed to combat, and may be influenced by family stressors upon return home.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample.

This longitudinal, retrospective cohort study used data from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS), which integrates 38 Army/DoD administrative data systems, including every system in which suicidal events are medically documented. The HADS includes individual-level person-month records for all soldiers on active duty between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 (n=1.66 million) (Kessler et al., 2013). This component of Army STARRS was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, University of California, San Diego, and Harvard Medical School, which determined that the present study did not constitute human participant research because it relies entirely on deidentified secondary data.

The HADS contains administrative records for the 975,057 Regular Army soldiers on active duty during the study period (excluding activated Army National Guard and Army Reserve), including 9,791 who had a documented suicide attempt. This study focused on Regular Army enlisted soldiers, who accounted for nearly 99% of suicide attempts from 2004 through 2009 (Ursano et al., 2015b), with the final analytic sample including all enlisted soldiers who attempted suicide (n=9,650 cases) and a 1:200 equal-probability sample of control person-months (n=153,528). In selecting controls, the population of enlisted soldiers was stratified by gender, rank, time in service, deployment status (never, currently, or previously deployed), and historical time. Control person-months excluded all soldiers with a documented suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) (Ursano et al., 2015a), and person-months in which a soldier died. Data were analyzed using a discrete-time survival framework with person-month as the unit of analysis (Willett and Singer, 1993), such that each month in the career of a soldier was treated as a separate observational record. Each control person-month was assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for under-sampling.

2.2. Measures.

2.2.1. Suicide attempt.

Soldiers who attempted suicide were identified using Army/DoD administrative records from: the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) (Gahm et al., 2012), a DoD-wide surveillance mechanism that aggregates information on suicidal behaviors via a standardized form completed by medical providers at DoD treatment facilities; and ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes E950-E958 (indicating self-inflicted poisoning or injury with suicidal intent) from the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR), Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS), and TRANSCOM (Transportation Command) Regulating and Command and Control Evacuating System (TRAC2ES), which together provide healthcare encounter information from military and civilian treatment facilities, combat operations, and aeromedical evacuations (eTable 1, available online at www.starrs-ls.org/#/list/publications). We excluded suicide deaths and DoDSER records indicating only suicide ideation. The E959 code (late effects of a self-inflicted injury) was excluded, as it confounds the temporal relationships between the predictor variables and suicide attempt (Walkup et al., 2012). Records from different data systems were cross-referenced to ensure all cases represent unique soldiers. For soldiers with multiple suicide attempts, we selected the first attempt using a hierarchical classification scheme that prioritized DoDSER records (Ursano et al., 2015a).

2.2.2. Socio-demographic and service-related variables.

Socio-demographic (gender, current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and service-related variables (age at Army entry, time in service [1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5+ years], deployment status [never, currently, or previously deployed], and military occupation [combat arms vs. other]) were drawn from Army/DoD administrative data (eTable 1). Combat arms included occupations that were identified, based on expert consensus, as those most typically exposed to direct combat. This includes some, but not all, of the occupations traditionally classified as combat arms (eTable 2). Previous research indicates that these combat arms soldiers are at elevated risk of suicide attempt compared to other occupations (Ursano et al., 2017). We also created an indicator variable for any prior mental health diagnosis during Army service by combining categories derived from administrative medical record ICD-9-CM codes (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, personality disorders), excluding postconcussion syndrome, tobacco use disorder, and supplemental V-codes that are not disorders (e.g., stressors/adversities, marital problems) (eTable 3).

2.2.3. Family violence.

Family violence events were identified using 2002–2009 administrative records from Army legal data systems (including family violence-related aggravated and/or simple assault, emotional and/or sexual abuse, and family-related non-violent offenses) and the Army Central Registry (ACR), a Family Services data system specifically designed to capture family violence-related events for the purpose of intervention (including spouse and child abuse, with physical, sexual, emotional, and neglect subtypes). Additional events were captured using family violence-related ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes, E codes, and V codes recorded from 2004–2009 in administrative medical records (eTables 4 and 5).

We constructed variables for: any history of family violence; number of family violence events; time since the most recent family violence event (i.e., number of months, not including month of suicide attempt or sampled control person-month); role in family violence events (perpetrator, victim only); and source of the family violence record (legal, ACR, or medical [ICD-9-CM]). Number of family violence events was calculated based on the number of calendar months in which family violence was administratively recorded. Given that a soldier can be both a perpetrator and a victim of family violence, “role” was determined based on a hierarchy in which soldiers who were ever identified as a perpetrator of family violence were classified as perpetrators and soldiers who were exclusively victims of family violence were classified as victims. Similarly, given that a soldier can have family violence records in multiple databases, we classified “source” based on a hierarchy in which soldiers with any previous legal record for family were classified as “legal,” those with an ACR record (but no legal record) were classified as “ACR”, and those with a medical record (but no legal or ACR record) were classified as “medical.”

We examined legal records for events that were classified as either founded or unfounded based on the results of a police investigation. A founded case classification indicates that there was adequate evidence that a Uniform Code of Military Justice, state/local code, international law, or other legal violation occurred, based on probable cause and supporting evidence. Unfounded cases indicate that there was no evidence that a criminal offense may have occurred. Similarly, we examined ACR records for events that were classified as either substantiated or unsubstantiated based on investigations by a multidisciplinary case review committee at the medical treatment facility of each Army installation. Substantiated incidents are those in which there is evidence of physical, emotional, and/or sexual maltreatment (Fuchs et al., 2005; McCarroll et al., 2008). In unsubstantiated incidents, there is evidence that the reported event did not occur or the investigation was unresolved.

2.3. Analysis.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2013). The association of all family violence variables with suicide attempt was first examined in univariable logistic regression analyses, followed by a series of multivariable logistic regression analyses that adjusted for socio-demographics (gender, current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and service-related characteristics (age at Army entry, time in service, deployment status, military occupation).

We then separately examined the interactions of any family violence history with gender, deployment status, and time in service to determine whether the association of family violence with risk of suicide attempt varied according to these important characteristics. Significant interactions were explored using stratified multivariable models. We also examined these interactions on an additive scale, with significance determined by relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), attributable proportion due to interaction (AP), and the synergy index (S). Logistic regression coefficients were exponentiated to obtain odds-ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Given that the outcome in the present study is a rare phenomenon, ORs approximate rate ratios (relative risk) (Rothman et al., 2012). Final model coefficients were used to generate a standardized risk estimate (SRE) (Roalfe et al., 2008) (number of suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) for each category of each predictor under the model assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means. All univariable and multivariable logistic regression models included a dummy predictor for calendar month and year to control for increasing rates of suicide attempt from 2004–2009 (Ursano et al., 2015a). Coefficients of other predictors can consequently be interpreted as averaged within-month associations based on the assumption that effects of other predictors do not vary over time. We also generated a discrete-time hazard function to estimate risk of suicide attempt in each month since the first family violence event among those with a history of family violence (448 suicide attempters, 2,556 control person-months).

3. Results

The majority of the sample was male (86.3%), 29 years old or younger (68.4%), younger than 21 years old when entered the Army (62.2%), White (59.8%), high school educated (76.5%), and currently married (54.7%). Almost three-quarters of soldiers (72.1%) had more than two years of Army service, 40.4% had never deployed, and 76.7% were assigned to a military occupation other than combat arms (eTable 6). Almost 3% (2.9%) of the sample had a history of family violence, either as a victim, a perpetrator, or both. A multivariable analysis (eTable 7) that adjusted for socio-demographics and service-related variables indicated that the odds of suicide attempt did not significantly differ based on whether a soldier’s family violence events were ever founded/substantiated versus only unfounded/unsubstantiated (OR=1.2 [95% CI: 1.0–1.4]). Based on these results and the rationale that even unfounded/unsubstantiated events indicate significant familial distress, all family violence events were included in subsequent multivariable analyses.

All family violence variables were associated with suicide attempt in univariable analyses (Table 1). After adjusting for socio-demographic and service-related variables, the association of any family violence history with suicide attempts remained significant (OR=2.9 [95% CI=2.6–3.2]; SRE=1,045/100,000 person-years [PY]). The odds of suicide attempt increased as the number of family violence events increased from one event (OR=2.6 [95% CI=2.4–2.9]; SRE=951/100,000 PY) to two or more events (OR=3.6 [95% CI=3.1–4.1]; SRE=1,296/100,000 PY), with pairwise analyses indicating that soldiers with two or more events had higher odds than those with only one event (OR=1.4 [95% CI=1.1–1.6]). Soldiers who experienced family violence in the previous month were almost five times more likely to attempt suicide than those with no family violence history (OR=4.8 [95% CI=3.9–5.9]; SRE=1,746/100,000 PY), with odds decreasing monotonically as time since the most recent family violence event increased to 13 months or more (OR=1.7 [95% CI=1.5–2.1]; SRE=632/100,000 PY). Odds of attempt were elevated for both perpetrators (OR=3.3 [95% CI=3.0–3.7]; SRE=1,194/100,000 PY) and those who were exclusively victims (OR=2.1 [95% CI=1.8–2.5] SRE=776/100,000 PY) compared to soldiers with no family violence history (Table 1). Pairwise analyses found that perpetrators had higher odds of suicide attempt than victims (OR=1.5 [95% CI=1.3–1.9]). Family violence was associated with elevated odds of suicide attempt regardless of whether the record source was legal (OR=3.2 [95% CI=2.8–3.6] SRE=1,149/100,000 PY), ACR (OR=2.9 [95% CI=2.5–3.3] SRE=1,043/100,000 PY), or medical (OR=2.1 [95% CI=1.7–2.7] SRE=776/100,000 PY). Pairwise analyses found no difference in odds of attempt between legal and ACR records, but both legal (OR=1.5 [95% CI=1.1–2.0]) and ACR (OR=1.3 [95% CI=1.0–1.8]) had increased odds relative to medical records. To further examine the robustness of family violence as a predictor of suicide attempt, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which an indicator for prior mental health diagnosis was added to the multivariable model. Although attenuated, the association of family violence with suicide attempt remained significant (any family violence history: OR=1.8 [95% CI=1.6–1.9]).

Table 1.

Univariable and multivariable associations of family violence with first suicide attempt among Regular Army enlisted soldiers.1

| Univariable2 | Multivariable3 | Cases (n) | Total (n)4 | Rate5 | Pop %6 | SRE7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||||

| I. Any history of family violence | |||||||||

| No | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 9,075 | 29,827,475 | 365 | 97.1 | 362 |

| Yes | 2.0* | (1.8–2.2) | 2.9* | (2.6–3.2) | 575 | 887,775 | 777 | 2.9 | 1,045 |

| χ21 | 263.0* | 563.5* | |||||||

| II. Number of family violence incidents | |||||||||

| No history of family violence | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 9,075 | 29,827,475 | 365 | 97.1 | 362 |

| 1 incident | 1.8* | (1.7–2.0) | 2.6* | (2.4–2.9) | 379 | 646,179 | 704 | 2.1 | 951 |

| 2+ incidents | 2.5* | (2.1–2.8) | 3.6* | (3.1–4.1) | 196 | 241,596 | 974 | 0.8 | 1,296 |

| χ22 | 281.2* | 586.2* | |||||||

| III. Time since most recent family violence incident | |||||||||

| No history of family violence | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 9,075 | 29,827,475 | 365 | 97.1 | 362 |

| 1 month | 6.2* | (5.1–7.6) | 4.8* | (3.9–5.9) | 95 | 49,295 | 2,267 | 0.2 | 1,746 |

| 2–3 months | 5.3* | (4.5–6.3) | 4.4* | (3.7–5.3) | 132 | 78,531 | 1,992 | 0.3 | 1,607 |

| 4–12 months | 2.6* | (2.2–3.0) | 3.1* | (2.7–3.5) | 196 | 238,396 | 993 | 0.8 | 1,111 |

| 13+ months | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 1.7* | (1.5–2.1) | 153 | 521,553 | 343 | 1.7 | 632 |

| χ25 | 828.4* | 735.7* | |||||||

| IV. Role in family violence8 | |||||||||

| No history of family violence | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 9,075 | 29,827,475 | 365 | 97.1 | 362 |

| Perpetrator | 2.0* | (1.8–2.2) | 3.3* | (3.0–3.7) | 423 | 654,023 | 776 | 2.1 | 1,194 |

| Victim | 2.0* | (1.7–2.4) | 2.1* | (1.8–2.5) | 152 | 233,752 | 780 | 0.8 | 776 |

| χ22 | 263.0* | 603.6* | |||||||

| V. Source of family violence record9 | |||||||||

| No history of family violence | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 9,075 | 29,827,475 | 365 | 97.1 | 362 |

| Legal record | 2.2* | (1.9–2.5) | 3.2* | (2.8–3.6) | 256 | 356,456 | 862 | 1.2 | 1,149 |

| ACR record | 1.8* | (1.6–2.0) | 2.9* | (2.5–3.3) | 256 | 459,856 | 668 | 1.5 | 1,043 |

| Medical record (ICD-9-CM) | 2.7* | (2.1–3.4) | 2.1* | (1.7–2.7) | 63 | 71,463 | 1,058 | 0.2 | 776 |

| χ23 | 280.2* | 578.1* | |||||||

The sample of enlisted soldiers (n=9,650 cases, 153,528 control person-months) is a subset of the total sample (n=193,617 person-months) from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Each family violence variable was examined in a separate univariable logistic regression model that also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Each family violence variable was examined in a separate logistic regression model that adjusted for socio-demographics (gender, current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and service-related variables (age at Army entry, time in service [1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5+ years], deployment status [never, currently, or previously deployed], and military occupation [combat arms vs. other]), and calendar time. Each model also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Total includes both cases (i.e., soldiers with a suicide attempt) and control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population (n=3.08 million).

Pop % = percent of the population of enlisted soldier.

SRE = Standardized risk estimates (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) were calculated assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means.

Given that an individual soldier can be both a perpetrator and a victim of family violence, we classified “role” based on a hierarchy, whereby soldiers who were ever a perpetrator of family violence were classified as perpetrators and soldiers who were exclusively victims of family violence were classified as victims.

Given that an individual soldier can have family violence records in multiple databases, we classified “source” based on a hierarchy, whereby soldiers with any previous legal record for family were classified as “legal,” those with an Army Central Registry (ACR) record (but no legal record) were classified as “ACR”, and those with a medical record (but no legal or ACR record) were classified as “medical.”

ACR = Army Central Registry

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

p < 0.05

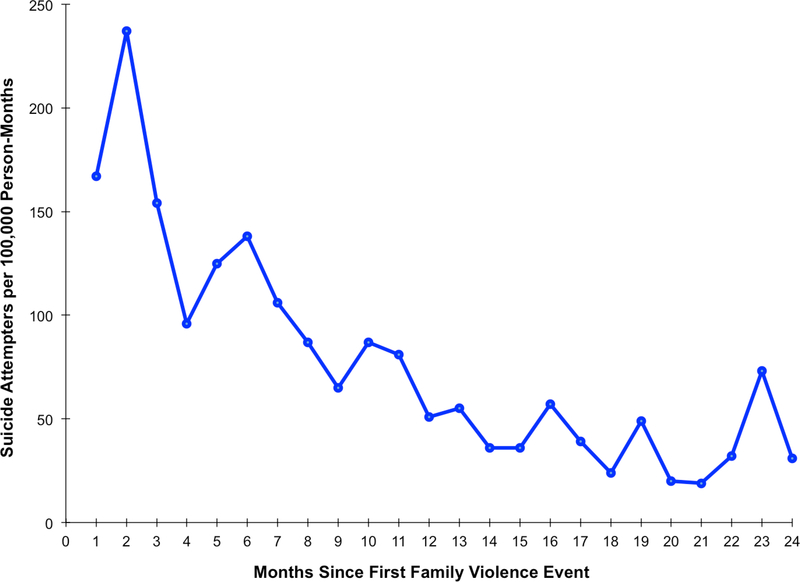

A discrete-time hazard model demonstrated greatly elevated risk of suicide attempt among enlisted soldiers during the seven month period following their first family violence event, with risk peaking in the second month (237/100,000 person-months), followed by a sharp decrease to 87/100,000 person-months by the eighth month. Risk of suicide attempt decreased to 51/100,000 person-months by twelve months following the first family violence event (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Monthly risk of suicide attempt by time since first family violence event among enlisted soldiers with a history of family violence.

1The sample of enlisted soldiers in the first two years after their first family violence event (n=448 cases, 2,556 control person-months) is a subset of the total sample (n=193,617 person-months) from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

2Monthly risk based on hazard rates and linear spline models.

To identify whether the effects of family violence history on suicide attempt are modified by gender, deployment status, and time in service, we examined each of these two-way interactions in separate multivariable models that adjusted for the other socio-demographic and service-related variables. The interactions of any family violence history with gender (χ21=47.4, p<0.0001) and deployment status (χ22=15.4, p<0.0005) were significant, but the interaction with time in service was not. To better understand these significant interactions, we examined a series of stratified multivariable models that adjusted for the socio-demographic and service-related covariates. When stratifying by gender, odds of suicide attempt were higher for both males (OR=3.4 [95% CI=3.1–3.8]; SRE=1,069/100,000 PY) and females (OR=2.1 [95% CI=1.8–2.5]; SRE=1,412/100,000 PY) with family violence history, although the effect of family violence was greater among males (Table 2). Stratifying by deployment status (Table 3), family violence was consistently associated with higher odds of suicide attempt among those never deployed (OR=2.5 [95% CI=2.2–2.9]; SRE=1,396/100,000 PY), currently deployed (OR=2.2 [95% CI=1.7–2.9]; SRE=311/100,000 PY), and previously deployed (OR=3.4 [95% CI=3.0–3.9]; SRE=959/100,000 PY). Pairwise analyses indicated that the OR of suicide attempt associated with family violence was larger for soldiers who were previously deployed versus never deployed (χ22=15.4, p<0.001), and there was no difference between soldiers who were previously or currently deployed.

Table 2.

Multivariate association of family violence with first suicide attempt among Regular Army enlisted soldiers stratified by gender.1,2

| Gender |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 139,717) |

Females (n = 23,461) |

|||||

| OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | |

| Any history of family violence | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | – | 313 | 1.0 | – | 673 |

| Yes | 3.4* | (3.1–3.8) | 1,069 | 2.1* | (1.8–2.5) | 1,412 |

| χ21 | 560.3* | 71.8* | ||||

The sample of enlisted soldiers (n=9,650 cases, 153,528 control person-months) is a subset of the total sample (n=193,617 person-months) from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Logistic regression models were adjusted for socio-demographics (current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and service-related variables (age at Army entry, time in service [1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5+ years], deployment status [never, currently, or previously deployed], and military occupation [combat arms vs. other]). Models also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

SRE = Standardized risk estimates (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) were calculated assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means.

p < 0.05

Table 3.

Multivariate association of family violence with first suicide attempt among Regular Army enlisted soldiers stratified by deployment status.1,2

| Deployment status |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never deployed (n = 67,971) |

Currently deployed (n = 36,801) |

Previously deployed (n = 58,406) |

|||||||

| OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | |

| Any history of family violence | |||||||||

| No | 1.0 | – | 558 | 1.0 | – | 152 | 1.0 | – | 280 |

| Yes | 2.5* | (2.2–2.9) | 1,396 | 2.2* | (1.7–2.9) | 331 | 3.4* | (3.0–3.9) | 959 |

| χ21 | 154.7* | 31.0* | 392.8* | ||||||

The sample of enlisted soldiers (n=9,650 cases, 153,528 control person-months) is a subset of the total sample (n=193,617 person-months) from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Logistic regression models were adjusted for socio-demographics (gender, current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and service-related variables (age at Army entry, time in service [1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5+ years], and military occupation [combat arms vs. other]). Models also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

SRE = Standardized risk estimates (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) were calculated assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means.

p < 0.05

When examined on an additive scale, there were significant interactions of family violence with deployment status and time in service, but not gender. The significant interaction of family violence with never deployed versus currently deployed (RERI=1.4 [95% CI=0.3–2.5]; AP=0.2 [95% CI=0.1–0.4]; S=1.4 [95% CI=1.1–1.9]) and previously deployed versus currently deployed (RERI=4.9 [95% CI=3.6–6.3]; AP=0.5 [95% CI=0.4–0.6]; S=2.3 [95% CI=1.8–2.9]) indicates that the effect of family violence on suicide attempt was modified by deployment status on an additive scale. This is also true for the significant additive interaction of family violence with 1–2 years versus 5 or more years of service (RERI=1.8 [95% CI=0.5–3.0]; AP=0.3 [95% CI=0.1–0.4]; S=1.5 [95% CI=1.2–1.9]) and 3–4 years versus 5 or more years of service (RERI=1.2 [95% CI=0.4–2.1]; AP=0.2 [95% CI=0.1–0.4]; S=1.4 [95% CI=1.1–1.8]).

We also examined whether the association of family violence role (perpetrator, victim only) with suicide attempt varied by gender and deployment status. The two-way interaction of family violence role by gender was significant (χ22=37.6, p<0.001) after adjusting for the socio-demographic and service-related covariates (military occupation was excluded for females since they were not permitted to serve in combat arms). After stratifying by gender (Table 4), being either a perpetrator or exclusively a victim was associated with suicide attempt in both males (perpetrator, OR=3.7 [95% CI=3.3–4.1], SRE=1,159/100,000 PY; victim only, OR=2.2 [95% CI=1.6–2.9], SRE=667/100,000 PY) and females (perpetrator, OR=1.7 [95% CI=1.3–2.4], SRE=1,175/100,000 PY; victim only, OR=2.3 [95% CI=1.9–2.8], SRE=1,547/100,000 PY). Pairwise analyses found that male perpetrators had higher odds of attempt than male victims (OR=1.7 [95% CI=1.3–2.3]), but female perpetrators and victims did not differ. The OR for male perpetrators was significantly larger than the OR for female perpetrators (χ21=37.5, p<0.0001), whereas the ORs for males and females who were exclusively victims did not differ (χ21=0.4451, p=0.5047). The two-way interaction of family violence role by deployment status was also significant (χ24=17.8, p=0.001), after adjusting for covariates. After stratifying by deployment status (eTable 8), being a perpetrator or exclusively a victim was associated with suicide attempt in soldiers who were never deployed (perpetrator, OR=3.1 [95% CI=2.6–3.7], SRE=1,729/100,000 PY; victim only, OR=1.8 [95% CI=1.4–2.3], SRE=1,018/100,000 PY), currently deployed (perpetrator, OR=2.0 [95% CI=1.5–2.8]), SRE=310/100,000 PY; victim only, OR=2.6 [95% CI=1.6–4.1], SRE=392/100,000 PY) and previously deployed (perpetrator, OR=3.7 [95% CI=3.2–4.2], SRE=1,037/100,000 PY; victim only, OR=2.7 [95% CI=2.1–3.4], SRE=743/100,000 PY). Pairwise analyses found that perpetrators had higher odds of suicide attempt than victims among those who were never deployed (OR=1.7 [95% CI=1.3–2.3]) and previously deployed (OR=1.4 [95% CI=1.1–1.8]); however, the odds for perpetrators and victims did not differ among soldiers who were currently deployed. Across deployment status, the OR for suicide attempt associated with family violence perpetration was significantly larger among soldiers who were previously deployed versus currently deployed (χ22=4.0, p=0.047) or never deployed (χ22=7.4, p=0.006). The OR for perpetrators who were never deployed did not differ from the OR for those who were currently deployed. The OR associated with family violence victimization was higher among soldiers who were currently deployed versus never deployed (χ22=7.7, p=0.005). The OR for victims who were previously deployed did not differ from the ORs for those who were currently or never deployed.

Table 4.

Multivariate association of role in family violence with first suicide attempt among Regular Army enlisted soldiers stratified by gender.1,2

| Gender |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 139,717) |

Females (n = 23,461) |

|||||

| OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | OR | (95% CI) | SRE3 | |

| Role in family violence4 | ||||||

| No history of family violence | 1.0 | -- | 313 | 1.0 | – | 673 |

| Perpetrator | 3.7* | (3.3–4.1) | 1,159 | 1.7* | (1.3–2.4) | 1,175 |

| Victim | 2.2* | (1.6–2.9) | 677 | 2.3* | (1.9–2.8) | 1,547 |

| χ22 | 588.1* | 75.9* | ||||

The sample of enlisted soldiers (n=9,650 cases, 153,528 control person-months) is a subset of the total sample (n=193,617 person-months) from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) that includes all Regular Army soldiers (i.e., excluding those in the U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve) with a suicide attempt in their administrative records during the years 2004–2009, plus a 1:200 stratified probability sample of all other active duty Regular Army person-months in the population exclusive of soldiers with a suicide attempt or other non-fatal suicidal event (e.g., suicidal ideation) and person-months associated with death (i.e., suicides, combat deaths, homicides, and deaths due to other injuries or illnesses). All records in the 1:200 sample were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for the under-sampling of months not associated with suicide attempt.

Logistic regression models were adjusted for socio-demographics (current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) and service-related variables (age at Army entry, time in service [1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5+ years], deployment status [never, currently, or previously deployed], and military occupation [combat arms vs. other]). Models also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

SRE = Standardized risk estimates (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) were calculated assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means.

Given that an individual soldier can be both a perpetrator and a victim of family violence, we classified “role” based on a hierarchy, whereby soldiers who were ever a perpetrator of family violence were classified as perpetrators and soldiers who were exclusively victims of family violence were classified as victims.

p < 0.05

4. Discussion

Soldiers with a documented history of family violence were almost three times as likely to attempt suicide as those with no history of family violence, with the risk of attempt increasing as the number and recency of family violence events increased. Suicide attempt risk was highest in the initial months following the first family violence event, followed by a sharp and generally steady decline as more time elapsed. Risk of suicide attempt was increased for both perpetrators of family violence and those who were exclusively victims. Risk was higher for those whose family violence was documented in legal or ACR (Family Services) records versus only medical records. These findings are supported by past research indicating that female military personnel who were victims of spousal abuse were over four times more likely to attempt suicide than non-victims (Belik et al., 2009). Assessment of suicide risk among soldiers would benefit from awareness of recent family violence events, and recognition of the association between family violence and suicide risk should be incorporated into evidenced-based family and marital therapies. There is a need for the development of interventions specific to suicidality following family violence and, more generally, suicide-specific interventions that consider context (e.g., Ursano et al., in press). It would also be beneficial to provide education on suicide risk to workers in the legal system and social support services.

Family violence was associated with suicide attempts in both male and female soldiers, with risk being higher among men. The gender difference appears to be related to whether a soldier had ever been a perpetrator of family violence. Although victims and perpetrators of both genders were at increased risk of attempting suicide, the pattern of risk associated with perpetration versus victimization differed for men and women. Specifically, the association of family violence victimization with suicide attempt was comparable for males and females, whereas the association of family violence perpetration with suicide attempt was significantly greater for males than females. Interestingly, male perpetrators had higher risk of suicide attempt than male victims, whereas risk among female victims and female perpetrators did not differ. Most family violence research is focused on victimization among females, and it is important to recognize the range of devastating consequences that many victims experience. Family violence victimization is associated with feelings of guilt and shame, psychological distress, and development of mental disorders in civilians and servicemembers (Dutton, 2003; O’Campo et al., 2006). These factors, in turn, are associated with increased risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Bhar et al., 2008; Carlson, 1997; Joiner, 2005). Importantly, family violence victimization is often underreported (Humphreys and Thiara, 2003). The increased incidence of perpetrators in this sample may be due to the nature of the sample, which was primarily male, and the use of documented versus self-reported family violence, which could result in under-representation of victims. Ensuring inquiry about family violence among those seeking medical care for injuries or for treatment of PTSD or depression provides an opportunity for suicide risk detection. Recent recommendations by the Institute of Medicine (2014) to enhance electronic health records by including social and behavioral determinants of health may also capture potentially significant information that requires further follow-up. Additional studies are needed to better understand the unique relationships of gender to suicide attempts in family violence perpetrators and victims, as these interrelationships have received little attention in previous research.

Family violence and time in service had a synergistic effect, such that soldiers who were early in their career and had a history of family violence were at greater than expected risk of suicide attempt. In addition, family violence was related to suicide attempt risk in soldiers who were previously, currently, or never deployed. This association was greater for soldiers who were previously deployed. Stress related to combat deployment and subsequent reintegration home may be associated with feelings of thwarted belongingness and isolation (Joiner, 2005; Selby et al., 2010). Combat exposure and PTSD are associated with postdeployment marital discord and parental distress (Gavlovski and Lyons, 2004; Gibbs et al., 2007; Marshall et al., 2005). Combat experiences, and subsequent family violence, expose soldiers to painful and provocative events, and may result in a greater capability for suicidal behavior (Bender et al., 2011). Further examination of the timing of family violence events relative to deployment and reintegration home can increase understanding of the relationships among deployment, family violence, and risk of suicide attempt. Previous research has also identified the role of exposure to traumatic events before military service, including history of child abuse and physical and sexual assault, in risk for suicidality (Afifi et al., 2016; Blosnich et al., 2014; Bryan et al., 2015; Cox et al., 2011; Gradus et al., 2012; Maguen et al., 2015; Perales et al., 2012). The robust association of childhood victimization with suicide attempt, as well as violence victimization and perpetration, in adulthood merits further attention.

Several limitations should be considered in the interpretation of the study findings. Although multiple data systems were examined to identify family violence events and suicide attempts, there may be cases that were not captured by these sources. Although rates of self-reported intimate partner violence among soldiers in previous studies are relatively higher (15.9%; Fonseca et al., 2006), those rates are based on non-representative samples that preclude direct comparison with the rate of documented family violence found in the present study’s representative sample. Importantly, documented cases provide an opportunity for immediate intervention to prevent both subsequent family violence and other adverse psychological and behavioral outcomes, such as suicidal behavior. It is also possible that family violence incidents leading to documented involvement with the legal or medical system are more severe than self-reported cases, resulting in associations with suicide attempt that are biased upwards. Future studies should address potential differences in suicide risk and other adverse outcomes associated with self-reported versus documented family violence.

Family violence and suicide attempt records are also subject to errors in clinician diagnosis and administrative/medical coding. As current study data focus exclusively on the 2004–2009 period, our findings may not generalize to earlier and later periods of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, or to other U.S. military conflicts. This study focuses on active duty Regular Army soldiers, which precludes analysis of risk and protective factors in Army National Guard and Army Reserve soldiers, or among veterans who have separated from the Army. We plan to include these important populations in future Army STARRS analyses. Finally, the observed differences across deployment status are not evidence of within-person changes in suicide attempt risk over time, as the composition of these groups is affected by the non-random nature of deployment and Army attrition (Ireland et al., 2012).

Family violence is a strong predictor of suicide attempts in soldiers. The magnitude of this association varies according to the recency, number of family violence incidents, and soldier’s role in the family violence event. Gender, deployment status, and whether the soldier was a victim versus perpetrator merit additional attention to better understand their role as modifiers in the relationship of family violence to suicide attempt. Primary prevention for soldiers who are at risk of family violence may help circumvent negative outcomes for both victims and perpetrators, and reduce the risk of suicidal behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Soldiers with a history of family violence had increased risk of suicide attempt.

Suicide attempt risk was highest in initial months following first family violence event.

Suicide attempt risk was elevated for family violence victims and perpetrators.

Family violence is an important risk factor for suicide attempt in soldiers.

Acknowledgements

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System)

Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan), James Wagner, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School)

Army liaison/consultant: Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (USAPHC (Provisional))

Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MA (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E. McCarroll, PhD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); CDR Patcho Santiago, MD, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); LTC Gary H. Wynn, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); and Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School).

Funding

Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001–15-2–0004). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, or the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Disclosure: Competing interests: In the past 3 years, Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis; was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, Shire, Takeda; and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. Stein has been a consultant for Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Healthcare Management Technologies, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Remedy Therapeutics, Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals and Tonix Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.

References

- Afifi TO, Taillieu T, Zamorski MA, Turner S, Cheung K, Sareen J, 2016. Association of child abuse exposure with suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts in military personnel and the general population in Canada. JAMA Psychiatry. 73, 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachynski KE, Canham-Chervak M, Black SA, Dada EO, Millikan AM, Jones BH, 2012. Mental health risk factors for suicides in the U.S. Army, 2007–8. Inj. Prev 18, 405–412. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belik SL, Stein MB, Asmundson GJ, Sareen J, 2009. Relation between traumatic events and suicide attempts in Canadian military personnel. Can. J. Psychiatry 54, 93–104. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender TW, Gordon KH, Bresin K, Joiner TE Jr., 2011. Impulsivity and suicidality: The mediating role of painful and provocative experiences. J. Affect. Disord 129, 301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhar S, Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Brown G, Beck AT, 2008. Self-esteem and suicidal ideation in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide Life. Threat. Behav 38, 511–516. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich JR, Dichter ME, Cerulli C, Batten SV, Bossarte RM, 2014. Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among individuals with a history of military service. JAMA Psychiatry. 71, 1041–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossarte RM, Knox KL, Piegari R, Altieri J, Kemp J, Katz IR, 2012. Prevalence and characteristics of suicide ideation and attempts among active military and veteran participants in a national health survey. Am. J. Public Health 102(suppl 1), S38–S40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Clemans TA, 2015. The association of military and premilitary sexual trauma with risk for suicide ideation, plans, and attempts. Psychiatry Res, 227, 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BE, 1997. A stress and coping approach to intervention with abused women. Fam. Relat 46, 291–298. doi: 10.2307/585127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli C, Stephens B, Bossarte R, 2014. Examining the Intersection Between Suicidal Behaviors and Intimate Partner Violence Among a Sample of Males Receiving Services From the Veterans Health Administration. Am. J. Mens Health 8, 440–443. doi: 10.1177/1557988314522828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Cox C, Duberstein PR, Tian L, Nisbet PA, Conwell Y, 2001. Violence, alcohol, and completed suicide: A case-control study. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 1701–1705. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DW, Ghahramanou-Holloway M, Szeto EH, Greene FN, Engel C, Wynn GH, Bradley J, Grammer G, 2011. Gender differences on documented trauma histories: Inpatients admitted to a military psychiatric unit for suicide-related thoughts or behaviors. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 199, 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, Kiss L, Schraiber LB, Deyessa N, Heise L, Durand J, Mbwambo J, Jansen H, Berhane Y, Ellsberg M, Garcia-Moreno C, WHO Multi-Country Study Team, 2011. Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Soc. Sci. Med 73, 79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG, 2003. The Abusive Personality: Violence and Control in Intimate Relationships. Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Green BL, Kaltman SI, Roesch DM, Zeffiro TA, 2006. Intimate partner violence, PTSD, and adverse health outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 21, 955–968. doi: 10.1177/0886260506289178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca CA, Schmaling KB, Stoever C, Gutierrez C, Blume AW, Russell ML, 2006. Variables associated with intimate partner violence in a deploying military sample. Mil. Med 171, 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C, Komp L, Bell N, McCarroll JE, Amoroso P, 2005. Transforming the Army Central Registry family violence file into a relational database for the purpose of facilitating epidemiological research. U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, MA: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a449982.pdf (accessed 11.04.16). [Google Scholar]

- Gahm GA, Reger MA, Kinn JT, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Bush NE, 2012. Addressing the surveillance goal in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: The Department of Defense Suicide Event Report. Am. J. Public Health 102(suppl 1), S24–S28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski T, Lyons JA, 2004. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: A review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggress. Violent Behav 9, 477–501. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00045-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs DA, Martin SL, Kupper LL, Johnson RE, 2007. Child maltreatment in enlisted soldiers’ families during combat-related deployments. JAMA. 298, 528–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradus JL, Shipherd JC, Suvak MK, Giasson HL, Miller M, 2012. Suicide attempts and suicide among marines: A decade of follow-up. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav 43, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver P, Fanslow J, 2013. Exploring risk factors for suicidal ideation in a population-based sample of New Zealand women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 37, 527–533. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heru AM, Stuart GL, Rainey S, Eyre J, Recupero PR, 2006. Prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence and associations with family functioning and alcohol abuse in psychiatric inpatients with suicidal intent. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 23–29. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys C, Thiara R, 2003. Mental health and domestic violence: “I call it symptoms of abuse.” Br. J. Soc. Work 33, 209–226. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/33.2.209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman J, Ireland R, Frost L, Cottrell L, 2012. Suicide incidence and risk factors in an active duty U.S. military population. Am. J. Public Health 102(suppl 1), S138–S146. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, 2014. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains in Electronic Health Records: Phase 1. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; Accessed at https://www.nap.edu/read/18709/chapter/1 on July 16, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland RR, Kress AM, Frost LZ, 2012. Association between mental health conditions diagnosed during initial eligibility for military health care benefits and subsequent deployment, attrition, and death by suicide among active duty service members. Mil. Med 177, 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, 2005. Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Zavlavsky AM, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, 2013. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 22, 267–275. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Snarr JD, Smith Slep AM, Heyman RE, Foran HM, United States Air Force Family Advocacy Program, 2011. Risk for suicidal ideation in the U.S. Air Force: An ecological perspective. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 79, 600–612. doi: 10.1037/a0024631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, Bell MR, Smith B, Boyko EJ, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, Ghamsary M, Hoge CW, 2013. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former U.S. military personnel. JAMA. 310, 496–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.65164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas DR, Wezner KC, Milner JS, McCanne TR, Harris IN, Monroe-Posey C, Nelson JP, 2005. Victim, perpetrator, family, and incident characteristics of infant and child homicide in the United States Air Force. Child Abuse Negl. 26, 167–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Smolenski DJ, 2015. Gender differences in suicide and suicide attempts among US Army soldiers. Psychiatry Res. 225, 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Panuzio J, Taft CT, 2005. Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen. Clin. Psychol. Rev 25, 862–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll JE, Newby JH, Dooley-Bernard M, 2008. Responding to domestic violence in the U.S. Army- The Family Advocacy Program. Family & Intimate Partner Violence Quarterly. 1, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Woods A, Jones S, Dienemann J, Campbell J, 2006. Depression, PTSD, and comorbidity related to intimate partner violence in civilian and military women. Brief Treat. Crisis Interv 6, 99–110. doi: 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhj010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perales R, Gallaway S, Forys-Donahue KL, Speiss A, Millikan AM, 2012. Prevalence of childhood trauma among U.S. Army soldiers with suicidal behavior. Mil. Med 177, 1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roalfe AK, Holder RL, Wilson S, 2008. Standardisation of rates using logistic regression: A comparison with the direct method. BMC Health Serv. Res. 8, 275. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, 2012. Modern epidemiology, 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelpia, PA, pp. 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc., 2013. SAS® 9.4 Software. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum M, Kessler RC, Gilman SE, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Cox KL, 2014. Predictors of suicide and accident death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 71, 493–503. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Bender TW, Ribeiro JD, Nock MK, Rudd MD, Bryan CJ, Lim IC, Baker MT, Gutierrez PM, Joiner TE Jr., 2010. Overcoming the fear of lethal injury: Evaluating suicidal behavior in the military through the lens of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Clin. Psychol. Rev 10, 298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Anderson M, Thompson MP, Crosby A, Sacks JJ, 2002. Assault victimization and suicidal ideation or behavior within a national sample of U.S. adults. Suicide Life. Threat. Behav 32, 42–50. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.42.22181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB, 2014. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 72, 107–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Cox KL, Naifeh JA, Fullerton CS, Sampson NA, Kao TC, Aliaga PA, Vegella P, Mash HH, Buckley C, Colpe LJ, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB, 2015a. Nonfatal suicidal behaviors in U.S. Army administrative records, 2004–2009: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 78, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1006512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, Herberman Mash HB, Fullerton CS, Bliese PD, Zaslavsky AM, Ng THH, Aliaga PA, Wynn GH, Dinh HM, McCarroll JE, Sampson NA, Kao T-C, Schoenbaum M, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, in press. Risk of suicide attempt among soldiers in Army units with a history of suicide attempts. JAMA Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, Herberman Mash HB, Fullerton CS, Ng THH, Aliaga PA, Wynn GH, Dinh HM, McCarroll JE, Sampson NA, Kao T-C, Schoenbaum M, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, 2017. Suicide attempts in U.S. Army combat arms, special forces and combat medics. BMC Psychiatry 17, 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Stein MB, Naifeh JA, Aliaga PA, Fullerton CS, Sampson NA, Kao T-C, Colpe LJ, Schoenbaum M, Cox KL, Heeringa SG, 2015b. Suicide Attempts in the U.S. Army during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2004–2009. JAMA. Psychiatry. 72, 917–926. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Townsend L, Crystal S, Olfson M, 2012. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying suicide or suicidal ideation using administrative or claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 21(suppl 1), 174–182. doi: 10.1002/pds.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD, 1993. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: Why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 61:952–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolford-Clevenger C, Febres J, Elmquist J, Zapor H, Brasfield H, Stuart GL: Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among court-referred male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Psychol. Serv 12, 9–15. doi: 10.1037/a0037338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.