Abstract

Background:

Natalizumab (NTZ) is sometimes discontinued in patients with multiple sclerosis, mainly due to concerns about the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. However, NTZ interruption may result in recrudescence of disease activity.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to summarize the available evidence about NTZ discontinuation and to identify which patients will experience post-NTZ disease reactivation through meta-analysis of existing literature data.

Methods:

PubMed was searched for articles reporting the effects of NTZ withdrawal in adult patients (⩾18 years) with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Definition of disease activity following NTZ discontinuation, proportion of patients who experienced post-NTZ disease reactivation, and timing to NTZ discontinuation to disease reactivation were systematically reviewed. A generic inverse variance with random effect was used to calculate the weighted effect of patients’ clinical characteristics on the risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation, defined as the occurrence of at least one relapse.

Results:

The original search identified 205 publications. Thirty-five articles were included in the systematic review. We found a high level of heterogeneity across studies in terms of sample size (10 to 1866 patients), baseline patient characteristics, follow up (1–24 months), outcome measures (clinical and/or radiological), and definition of post-NTZ disease reactivation or rebound. Clinical relapses were observed in 9–80% of patients and peaked at 4–7 months, whereas radiological disease activity was observed in 7–87% of patients starting at 6 weeks following NTZ discontinuation. The meta-analysis of six articles, yielding a total of 1183 patients, revealed that younger age, higher number of relapses and gadolinium-enhanced lesions before treatment start, and fewer NTZ infusions were associated with increased risk for post-NTZ disease reactivation (p ⩽ 0.05).

Conclusions:

Results from the present review and meta-analysis can help to profile patients who are at greater risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation. However, potential reporting bias and variability in selected studies should be taken into account when interpreting our data.

Keywords: discontinuation, meta-analysis, natalizumab, relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Natalizumab (NTZ) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against α4-integrin that is approved for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS).1,2 Whereas NTZ is associated with good overall long-term efficacy and tolerability,3 prolonged treatment with NTZ is known to increase the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) by opportunistic infection with John Cunningham virus (JCV).4

Three factors have been identified as increasing the risk of PML in NTZ-treated patients: (i) longer treatment duration, especially beyond 2 years; (ii) prior exposure to immunosuppressants (e.g. mitoxantrone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and/or mycophenolate mofetil); and (iii) the presence of anti-JCV antibodies in serum.5–8 Patients without a prior history of immunosuppressant use but with a high anti-JCV antibody index are also considered at higher risk of PML.7,9 Infection by JCV is a prerequisite for the development of PML, but patients who are anti-JCV antibody negative are still at risk for PML due to the potential for a new JCV infection or a false-negative test result. A recently published meta-analysis collecting data from 10 studies showed a mean seroconversion rate of 10.8% per year, and the average annual seroreversion rate (i.e. changing back to anti-JCV antibody negative status, as assessed in three studies) was 5.4%.10 In the seven studies incorporating index into the evaluation of serostatus change, the average percentage of patients converting from anti-JCV antibody negative with subsequent index values >0.9 was 3.5% per year.10 However, studies of seroconversion are subject to bias and many have limited follow-up time. In a longitudinal study over 6 years, the annual serostatus change was approximately 3%, and index category changes were more likely in patients with an index close to the category threshold.11

Despite published PML risk estimates for anti-JCV antibody positive patients to enable risk stratification9 and patient monitoring guidance to minimize PML risk,12 there is presently no consensus on how to manage patients at high risk of PML discontinuing NTZ or on the optimal protocols for its cessation. In the effort to optimize treatment when discontinuation of NTZ is required, a large number of studies have investigated switching and other so-called ‘bridging’ strategies to avoid return to pretreatment relapse rate levels and subsequent disability. There are currently no guidelines for treatment switching post-NTZ; but just one randomized clinical trial, namely RESTORE,13 and several observational studies providing mixed results.14–22 Although there is some evidence that such discontinuation strategies may be effective in the prevention of PML,23 the possibility of carryover PML should be considered in patients who switch from NTZ to alternative treatment.24,25 Complicating the consideration of PML risk during continuation of NTZ treatment in high-risk cases, most studies have shown that interruption of NTZ is often associated with return of disease activity that appears to be consistent with the known pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of NTZ following discontinuation.26–28

In an effort to shed more light on this important issue of NTZ discontinuation, this systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes and assesses the available clinical evidence on discontinuation of NTZ in patients with RRMS. This is especially important in trying to predict which patients will experience post-NTZ disease reactivation.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the meta-analysis, studies must involve adult patients (⩾18 years) with RRMS, have a minimum follow up of 4 weeks after NTZ cessation, and have studying the effects of withdrawal of NTZ in patients with RRMS as a major aim.

Electronic sources and search

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses statement,29 an electronic search of the literature published in English through March 2016 was carried out using PubMed, with no limitations based on publication status. The search string was based on the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms ‘natalizumab’, ‘discontinuation’, ‘interruption’, ‘suspension’, and ‘withdrawal’, which were used in different combinations (Supplementary File 1).

Study selection and quality assessment

The authors screened abstracts and full texts of the retrieved references to determine whether they were appropriate for inclusion in the present analysis. The authors independently extracted the data from each original publication, including the first author’s name, the year of publication, the number of patients, patient characteristics, the duration of follow up, and outcomes. Only original research articles were considered eligible for inclusion; reviews, case reports, and very small series (fewer than five patients) were excluded. No attempt was made to retrieve abstracts presented at scientific meetings given the limited information that these would provide in the context of this analysis. Assessment of the eligibility of publications for inclusion was performed by the authors, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Meta-analysis

We performed a generic inverse variance with random-effect models using Review Manager version 5.3.5 (RevMan, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) to calculate the weighted effect of patients’ clinical characteristics on the risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation, defined as the occurrence of at least one clinical relapse after NTZ withdrawal and before initiation of another disease-modifying treatment (DMT). Only studies in which there was a clear distinction between patients who experienced post-NTZ disease reactivation and those who did not entered in the quantitative analysis. Studies from the same groups potentially reporting overlapped data were carefully checked to select only the most informative. Forest plots for each variable of interest were generated, which included sex, age, disease duration, the number of relapses in the year prior to NTZ start, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, the number of gadolinium-enhanced (Gd+) lesions at pre-NTZ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and the total number of infusions received before treatment discontinuation. Results are presented as risk differences or standardized mean differences (with 95% confidence intervals) for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. The heterogeneity of included studies was addressed by the estimation of Tau2 and I2, with an I2 value <40% considered an indicator of marginal heterogeneity. Potential publication bias of included studies was determined by Egger p value.

Results

Study selection

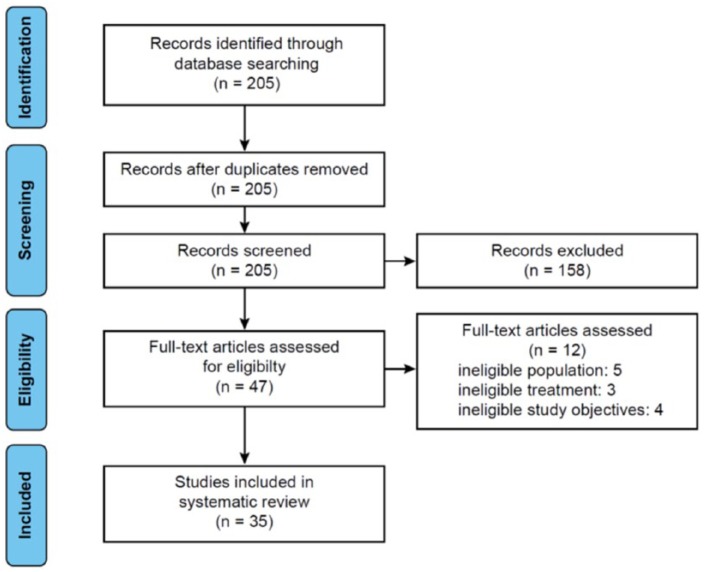

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of study selection from the initial results of the publication searches to final inclusion or exclusion. The original literature search identified 205 publications. After removal of duplicates and title/abstract screening, 158 records were excluded based on not being relevant to RRMS, not directly examining the clinical consequences of NTZ discontinuation, or being case reports or commentaries/editorials. Excluded publications are listed in Supplementary File 2. Forty-seven articles were then assessed for eligibility through review of full text. Of these, 12 were excluded based on the patient population, treatments, or study objectives. Thus, a total of 35 articles were included in the present systematic review. Even if including patients with progressive multiple sclerosis, we did not exclude the studies by West and colleagues30 and Miravalle and colleagues31 whose results were mainly based on patients with RRMS.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of evaluation process for the systematic review and meta-analysis.

These studies, which were published between 2008 and 2016, were highly heterogeneous with regard to the number of patients, follow up, the measurement of disease activity, and other relevant criteria (Table 1).13–21,26–28,30–32,34–53 We identified several articles at high risk of overlapped data because published by the same group.15,17,19,20,27,32–39 The various parameters considered are analyzed separately in the following.

Table 1.

Studies investigating natalizumab discontinuation in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis.

| Study | Study design (follow up)* |

Sample size |

Time of

NTZ interruption (washout) |

Post-NTZ treatment |

Reported % with relapses | Reported % with MRI activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borriello et al.32 | Single-center, prospective | n = 21 | Mean: 111.5 days Interval: 90–180 days |

None | 19% | 47.4% |

| Borriello et al.15 | Single-center, prospective | n = 23 | Mean: 117 (±14.8) days Interval: 90–150 days |

Pulse MPL | 17.4% | 30.4% |

| Capobianco et al.20 | Single-center, retrospective (1–12 months) |

n = 79 | 1 to 3 months | None (n = 24) FTY (n = 35) Other treatments (AZA, GA, IFNB, steroids) (n = 20) |

31.4% (FTY) 41.8% (None + other treatments) |

Not reported |

| Clerico et al.40 | Multicenter, prospective (12 months) |

n = 124 | No washout except for FTY (3-month WO) | Continued NTZ (n = 43) GA, IFNB, FTY or MTX (n = 81) |

Not reported (median number of relapses in NTZ interrupters = 1) |

48.1% in NTZ interrupters |

| Cohen et al.41 | Multicenter survey on prospectively collected data (6 months) |

n = 333 | Mean: 17 weeks Interval: 2–156 weeks |

FTY | 27% | Not reported |

| Ferré et al.37 | Single-center, retrospective (12 months) |

n = 15 | 1st withdrawal: ~1 month 2nd withdrawal: ~4 months |

1st withdrawal: GA (n = 12),

IFNB (n = 2), none (n =

1) 2nd withdrawal: FTY (n = 12), IS (n = 2), RTX (n = 1) |

1st withdrawal: 80% 2nd withdrawal: 73.5% |

1st withdrawal: 87% 2nd withdrawal: 60% |

| Fox et al.13 | Phase IV, randomized, partially PBO-controlled exploratory

study (24 months) |

n = 175 | GA and IFNB: 0 days PBO: 4 weeks MPL: 12 weeks |

Continued NTZ (n = 45) PBO (n = 42) GA (n = 17) IFNB (n = 17) MPL (n = 54) |

Continued NTZ: 4% PBO: 17% GA: 27% IFNB: 29% MPL: 15% |

Continued NTZ: 0% PBO: 46% GA: 53% IFNB: 7% MPL: 40% |

| Gobbi et al.42 | Randomized, rater-blinded, parallel-group, pilot

study (12 months) |

n = 19 | IFNB: 30 days | Continued NTZ (n = 10) IFNB (n = 9) |

Continued NTZ: 0% IFNB: 22% |

Continued NTZ: 37.5% IFNB: 75% |

| Grimaldi et al.28 | Bi-center, prospective, examination of 386 MRI scans | n = 166 | MRI scans obtained from 1 to ⩾13 weeks after the last NTZ infusion | None | Not reported | Whole sample: 12.2% Scans obtained >4 weeks after the last NTZ infusion (n = 113): 23.1% |

| Havla et al.17 | Multicenter, prospective (~12 months) | n = 36 | Median: 13.7 weeks IQR: 5.4 weeks |

None (n = 10) FTY (n = 26) |

No DMT: 70% FTY: 42% |

No DMT: 67% FTY: 9% |

| Hoepner et al.36 | Multicenter, retrospective (12 months) |

n = 33 | Mean: 14.9 (±4.7) weeks | FTY | During washout: 61% During FTY treatment: 48% |

Not reported |

| Iaffaldano et al.21 | Multicenter, observational, (12 months) | n = 613 | Median: 2.5 months IQR: 4.3 months |

GA or IFNB (n = 298) FTY (n = 135) |

During washout: 19.4% During GA or IFNB: 15% During FTY treatment: 27% |

Not reported |

| Jokubaitis et al.18 | Multicenter, observational (~10 months) | n = 536 | Median: 79 days IQR: 39 days |

FTY (n = 89) | 20.2% | Not reported |

| Kappos et al.43 | Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled

trial (24 weeks) |

n = 142 | Randomization in a 1:1:1 ratio to different washout periods:

8 weeks (n = 50); 12 (8+4 PBO) weeks (n = 42); or 16 (8+8 PBO) weeks (n = 50) from last NTZ infusion |

FTY | During washout: 8 weeks group: 4% 12 weeks group: 0% 16 weeks group: 10% During FTY treatment: 8 weeks group: 12% 12 weeks group: 9.5% 16 weeks group: 26% |

During washout: 8 weeks group: 14% 12 weeks group: 26% 16 weeks group: 58% During FTY treatment: 8 weeks group: 39% 12 weeks group: 45% 16 weeks group: 68% |

| Kaufman et al.44 | Post hoc analysis of RESTORE: phase IV, randomized, partially PBO-controlled exploratory study | n = 175 | GA and IFNB: 0 days PBO: 4 weeks MPL: 12 weeks |

Continued NTZ (n = 45) PBO (n = 42) GA (n = 17) IFNB (n = 17) MPL (n = 54) |

– | Continued NTZ: 0% PBO: 61% Other treatments: 48% (Gd+ lesions detection started at week 12; most were observed at ⩾week 16) |

| Kerbrat et al.45 | Multicenter, observational (~6 months) | n = 27 | ⩽6 months | None | 67% | 68% |

| Killestein et al.46 | Single-center, prospective (6 months) | n = 10 | Mean: 17 weeks Interval: 8–22 weeks |

None | 70% | 80% |

| Lo Re et al.38 | Multicenter, retrospective (12 months) |

n = 132 | Median: 5 months | None (n = 28) NTZ restart (n = 9) FTY (n = 57), “first-line” DMT (IFNB, GA, TER, AZA) (n = 16) IS (n = 4) AHSCT (n = 2) |

54.5% | 48% |

| Magraner et al.14 | Multicenter, prospective (~10 months) |

n = 18 | 3 months | MPL followed by GA | During washout: 0% At month 6: 16.6% At follow-up: 33.3% |

During washout: 0% At month 6: 55.5% |

| Melis et al.47 | Single-center, retrospective (12 months) |

n = 54 | ~3–4 months | None (n = 35) or MPL (n =

19) followed by: NTZ restart (n = 24) Unspecified immunomodulants (n = 11) IS (n = 5) FTY (n = 2) |

57.4% | 47.1% |

| Miravalle et al.31 | Single-center, prospective | n = 32 | Mean: ~4 months | None | 38% | Not reported |

| O’Connor et al.26 |

Post hoc analysis of AFFIRM, SENTINEL, and

GLANCE (12 months) |

n = 1,866 | ~8 months | None: ~87% Alternative DMT (GA or IFNB): ~13% |

21% | ~35% |

| Prosperini et al.39 | Multicenter, retrospective (6 years from NTZ start) |

n = 415 | Not reported | Discontinuing NTZ (n = 122): FTY (n = 55) GA (n = 36) IFNB (n = 12) MTX (n = 2) AZA (n = 2) CYC (n = 2) RTX (n = 1) None (n = 12) |

Mean cumulative no. of relapses was 0.39 in NTZ continuers versus 1.45 in NTZ discontinuers (p < 0.001) | Not reported |

| Rinaldi et al.16 | Single-center, prospective (6–10 months) |

n = 22 | 3 months | FTY | 23% | 45% |

| Rossi et al.34 | Bi-center, prospective (12 months) |

n = 40 | 4 weeks | GA | 37.5% | 56% |

| Rossi et al.35 | Bi-center, prospective (6 months) |

n = 93 | 4 weeks | Continuing NTZ (n = 37) GA (n = 37) IFNB (n = 19) |

69.6% of NTZ discontinuers had relapses and/or MRI reactivation | |

| Rossi et al.19 | Single-center, retrospective (6 months) |

n = 105 | 4 weeks | GA (n = 40) GA + MPL (n = 40) IFNB (n = 25) |

GA: 35% GA + MPL: 60% IFNB: 76% |

GA: 56% GA + MPL: 84.6% IFNB: 50% |

| Salhofer-Polanyi et al.48 | Multicenter survey on retrospectively collected

data (12 months) |

n = 201 | Median: 3 months Interval: <3–12 months |

None (n = 28) Alternative DMT (FTY, GA, NTZ restart, ⩾1 DMT) (n = 176) |

60.9% | 30% |

| Sangalli et al.27 | Single-center, prospective (~22.4 months) |

n = 110 | ~1 month | GA (n = 72) IFNB (n = 18) FTY (n = 10) None (n = 10) |

56% at 1 year of follow up | 65% at 1 year of follow up |

| Sempere et al.49 | Single-center, prospective (4–12 months) |

n = 18 | 3 months | MPL followed by FTY (n = 8) | 63% | 71% after 9 months from NTZ interruption |

| Sorensen et al.50 | Multicenter survey on prospectively collected

data (3–12 months) |

n = 375 | Mean: 3.8 months Interval: 0–53.3 months |

FTY (n = 244) MTX (n = 36) NTZ restart (n = 30) GA (n = 15) IFNB (n = 14) Unspecified DMT (n = 17) None (n = 10) |

0–3 months after NTZ discontinuation: 16.8% 4–6 months after NTZ discontinuation: 10.9% 7–9 months after NTZ discontinuation: 9.9% 10–12 months after NTZ discontinuation: 5.8% |

Not reported |

| Stuve et al.51 | Longitudinal assessment following suspension of NTZ phase

III trials (14 months) |

n = 23 | Not reported | None (n = 4) IFNB (n = 15) IFNB + MMF (n = 1) GA (n = 1) GA + MMF (n = 1) Unknown (n = 1) |

~9% | No significant difference after NTZ interruption |

| Vellinga et al.52 | Longitudinal assessment, following suspension of NTZ phase III trials | n = 21 | ~15 months | None | Median annual relapse rate was 1.15 in the pretreatment interval and 0.73 in the post-withdrawal interval (p = ns). | Median annualized number of active T2 lesions was higher in the post-withdrawal interval than in the pretreatment interval (10.32 versus 3.43, p = 0.014) |

| Vidal-Jordana et al.53 | Single-center, prospective (12 months) |

n = 47 | Mean: 6.8 months | None (n = 25) or MPL (n = 22) followed by another unspecified DMT (n = 31) | 70% | 53.2% |

| West et al.30 | Single-center, retrospective | n = 68 | 6 months | None (n = 64) Unspecified DMT (n = 4) |

28% | 32% |

AHSTC, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ARR, annualized relapse rate; AZA, azathioprine; CYS, cyclophosphamide; DMT, disease-modifying treatment; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; FTY, fingolimod; GA, glatiramer acetate; IFNB, interferon beta; IQR, interquartile range; IS, immunosuppressants; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPL, methylprednisolone; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MTX, mitoxantrone; NTZ, natalizumab; PBO, placebo; RTX, rituximab; TER, teriflunomide.

Study design and sample size

As expected, the designs of the 35 studies varied widely. Only five of the studies were randomized trials (two post hoc analyses);13,26,42–44 the remainder were longitudinal assessment following suspension of phase III trials on NTZ (2),51,52 prospective (15)14–17,27,28,31,32,34,35,40,46,49,50,53 or retrospective analyses (11),18–21,30,36–39,45,47 and two multicenter surveys on prospectively collected data (i.e. treating physicians were asked to fill in an ad hoc questionnaire).41,48 The majority of studies involved a relatively small number of patients. The smallest was that of Killestein and colleagues,46 with 10 patients, whereas the largest was that of O’Connor and colleagues,26 a post hoc analysis of 1866 patients from the AFFIRM, SENTINEL, and GLANCE trials who voluntarily suspended NTZ. The second-largest analysis was an observational prospective cohort study by Iaffaldano and colleagues involving 613 patients,21 followed by another observational study by Jokubaitis and colleagues in 536 patients.18 The largest randomized trial was that of Fox and colleagues,13 in which 175 patients were allocated 1:1:2 to continue NTZ (n = 45), switch to placebo (n = 42), or switch to other therapies (n = 88) for 24 weeks.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics, when provided, were similar between studies. Pre-NTZ mean disease duration was reported in 27 articles13–19,21,27,28,31,34–37,39,40,42–45,48–50,52,53 and was in the range of 5–11 years. Average (mean or median) EDSS at baseline was reported in 25 articles13–15,17–19,21,26,27,31,34,38–45,47–49,50,53 and was in the 2.0–5.0 range. Pre-NTZ mean annualized relapse rate (ARR) was reported in 22 articles14,17,19,21,27,30,32,34–42,45–50,52 and was in the 0.9–2.5 range. Duration of NTZ treatment was less well defined, with 9 articles13,15,17,21,27,31,40–42 reporting the mean number of infusions (in the 19–31 range) and 15 articles14,18,26,32,34–36,39,43–46,48,49,53 reporting the mean or median duration of therapy (in the range of 1–3.5 years).

Reasons for discontinuation of NTZ

The most common reason for discontinuation of NTZ was by far fear and/or risk of PML, cited by 22 (63%) of the 35 studies. Only 10 (29%) studies used the STRATIFY test for anti-JCV antibodies to assess risk for some or all patients, though it should be noted that this test was not available until 2011. Other reasons for discontinuation of NTZ were also cited, including drug holiday (otherwise unspecified), family planning/pregnancy, patient choice. ‘Lack of efficacy’, ‘efficacy issue’, ‘inefficacy’, or ‘treatment failure’ were reported in 10 articles as the main reason for NTZ discontinuation in 5.5–20.1% of NTZ interrupters, according to different studies.14,17,21,30,36,38,41,48,50,53 There were no clear differences observed between earlier and more recent studies in reasons given for discontinuation.

Washout duration and follow up

A total of 33 articles reporting detailed information about the washout period, i.e. the time elapsed between the last NTZ infusion and the end of observation (5 articles)15,31,32,44,45 or the start of another DMT (28 articles).13,14,16–21,26,27,30,34–38,42,44,52,40,41,43,45,47–50,53 The washout period was in the range of 1–12 months.

Follow-up duration ranged from 1 to 24 months after NTZ discontinuation, with only one study comparing the 6-year follow-up data (from treatment start) of patients who continued or discontinued NTZ treatment after a median time of 3.5 years.39

Definition of disease activity following NTZ discontinuation

A wide range of definitions of disease activity were used. Many of these included clinical disease activity (proportion of relapse-free or ARR) as well as EDSS score and MRI results. Imaging criteria for disease activity varied greatly, sometimes including one or more lesions (of particular or undefined dimension). In particular, seven studies used relapses alone,18,21,35,36,41,49,50 4 used MRI alone,28,32,44,52 16 used relapses and MRI,13–17,19,20,26,27,30,31,34,37,38,45,46 and 2 relapses and EDSS;29,53 and 6 used ARR, EDSS, and MRI.40,42,43,47,48,51

For consistency, we use the term post-NTZ disease reactivation to refer to disease activity following NTZ discontinuation, and we specify the form of activity (relapses and/or MRI activity), reporting proportion of patients who reached outcome(s), when this information was available (Table 1). We did not report data on EDSS change because all but one article had a too short follow up to draw conclusion on long-term risk of disability accrual.

The majority of studies made no attempt to distinguish post-NTZ disease reactivation from rebound. At present there is no agreed-upon definition of the rebound phenomenon, but it commonly indicates worsening of disease activity to levels greater than pretreatment levels following discontinuation of NTZ. Only 4 of the 35 studies20,41,45,50 provided a definition of rebound. Capobianco and colleagues20 defined rebound as the recurrence of disease activity with either the more than three Gd+ or ‘tumor-like’ lesions visible on MRI or a severe relapse with an increase in EDSS score of >1.0 point. Sorensen and colleagues50 set out a higher individual relapse rate after cessation of NTZ than before NTZ as the primary criterion of rebound. Lo Re and colleagues38 defined rebound as the recurrence of disease activity with at least two of the following features: (i) an ARR increase in comparison with pre-NTZ disease course; (ii) one or more severe relapses with sustained disability progression (one-step EDSS increase); (iii) three or more new large T2 lesions and/or Gd+ lesions on MRI; and (iv) one or more new tumor-like demyelinating lesions on MRI. Kerbrat and colleagues45 restricted rebound to cases with both severe relapse and 20 Gd+ lesions on MRI in the 6 months after NTZ discontinuation.

Rebound versus post-NTZ disease reactivation

Despite the lack of a shared definition and heterogeneity, the percentage of patients experiencing rebound was reported in eight studies, ranging from 8% to 22% according to different studies. Havla and colleagues,17 Miravalle and colleagues,31 Rinaldi and colleagues,16 Vellinga and colleagues,52 and West and colleagues,30 all report disease activity being increased over pretreatment levels in a small proportion of patients after discontinuation of NTZ. Rebound effects were notably absent from the large study by O’Connor and colleagues26 as well as from the studies by Kaufman and colleagues,44 Magraner and colleagues,14 Rossi and colleagues,19 and Stuve and colleagues.51 These apparent discrepancies may be due to differences in follow-up duration, the number of patients (as many cohorts were small), pre-NTZ disease activity, the adopted definition of rebound.

Post-NTZ disease reactivation was reported in a highly variable proportion of patients in the different studies. Relapses were reported by 9–80% of patients among those interrupting NTZ, generally starting at 3 months, peaking at 4–7 months, and returning at the pre-NTZ interruption level at approximately 12 months.16,26,27,30,36,45,47,49,50

Data on MRI activity were reported in 27 articles. MRI activity, expressed as Gd+ lesions, generally first detected approximately at 6–7 weeks post-discontinuation.28 The proportions of patients with MRI activity varied widely according to washout duration and type of treatment administered following NTZ. The smaller proportion of patients with MRI activity (7%) was observed among the group randomized to interferon beta in the RESTORE trial.13 The greater proportion of patients with MRI activity was reported by Ferré and colleagues37 (87%) despite the switch to alternative DMT (glatiramer acetate and interferon beta) at 1 month post-NTZ discontinuation.

Risk factors for post-NTZ disease reactivation

In the largest study, the post hoc analysis of data from AFFIRM, SENTINEL, and GLANCE by O’Connor and colleagues,26 post-NTZ disease reactivation (increased ARR) was observed regardless of overall NTZ exposure, whether or not patients received alternative DMTs, and whether or not patients had highly active MS disease. In the study by Sangalli and colleagues,27 higher pretreatment NTZ disease activity, defined as an ARR of 3 or more in the year prior to NTZ start and/or at least three Gd+ lesions at baseline brain MRI, was correlated with an increased risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation (occurrence of relapses and/or MRI activity). Moreover, even with alternative DMTs, the risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation peaked between the second and the eighth month after NTZ suspension.27

Eight studies reported an increased risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation even after starting an alternative DMT, especially in case of longer washout period (more than 2–4 months).17,18,21,38,41,43,48,50

In the large investigation by Iaffaldano and colleagues,21 an increased risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation (as assessed by number of relapses) during the washout period was also found in patients with a higher number of relapses before NTZ treatment [incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 1.31, p = 0.0014], whereas the strongest independent factors influencing relapse risk after the start of switch therapies were a washout duration longer than 3 months (IRR = 1.78, p < 0.0001), the number of relapses experienced before (IRR = 1.13, p = 0.0118) and during (IRR = 1.61, p < 0.0001) NTZ treatment, and the presence of comorbidities (IRR = 1.4, p = 0.0097).21

Vidal-Jordana and colleagues53 reported the following about predictors of different types of post-NTZ disease reactivation: (i) post-NTZ relapses were predicted by experiencing either relapses or a one-step EDSS increase while on NTZ treatment; (ii) a two-step EDSS increase was predicted by higher baseline EDSS score and one-step EDSS increase while on NTZ treatment; and (iii) Gd+ lesions were predicted by a higher number of pretreatment Gd+ lesions, a higher baseline EDSS score, and a one-step EDSS increase while on NTZ treatment.

Joukubaitis and colleagues18 reported that the number of relapses in the 6 months prior to NTZ start [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.59 per relapse; p = 0.002] and a gap in treatment (i.e. time elapsed from NTZ discontinuation to the next DMT administration) of 2–4 months compared with no gap (HR = 2.10; p = 0.041) were independent predictors of post-NTZ disease reactivation (time to first relapse on fingolimod).

Although the study by Grimaldi and colleagues28 was not specifically designed to investigate post-NTZ disease reactivation, they found that the risk of MRI activity (Gd+ lesions) in patients with delayed NTZ dosing (i.e. more than 7 up to 12 weeks) was higher with shorter treatment duration (odds ratio = 0.92 per infusion; p = 0.006), confirming previous data from Vellinga and colleagues.52

Other studies did not investigate or did not report on risk factors for post-NTZ disease reactivation, though this is not necessarily unexpected, as many were small studies and not powered to reveal such differences.

Risk of sustained disability accrual after NTZ discontinuation

Nearly all studies exploring the consequences of NTZ discontinuation had follow-up times of 12–15 months or less. It is thus of interest to evaluate the risk–benefit profile of NTZ at longer periods to determine the risk of PML and worsening of disability, as was done in the study by Prosperini and colleagues.39 Of the 415 patients followed in this study, 318 received standard NTZ treatment without showing evidence of disability worsening in the first 2 years and were included in the 6-year follow-up analysis, with 61.6% remaining on treatment and 38.4% discontinuing (after a median time of 3.5 years). Patients in the discontinuing group had more than twice the risk of sustained disability worsening (HR = 2.3; p = 0.007), and a 68% lower likelihood of disability reduction (HR = 0.31; p = 0.009) compared with the continuing group.

The risk of sustained disability worsening in the discontinuing group increased with older age (HR = 1.04 per year; p = 0.04) and greater EDSS score (HR = 1.43 per step; p = 0.004). In case of NTZ discontinuation, the overall risk of disability worsening is 1 in 3, increasing to 1 in 2 if the EDSS score at start of NTZ treatment is greater than 3.0. These results highlight the need for further confirmatory studies on disability worsening in the long term.

Meta-analysis

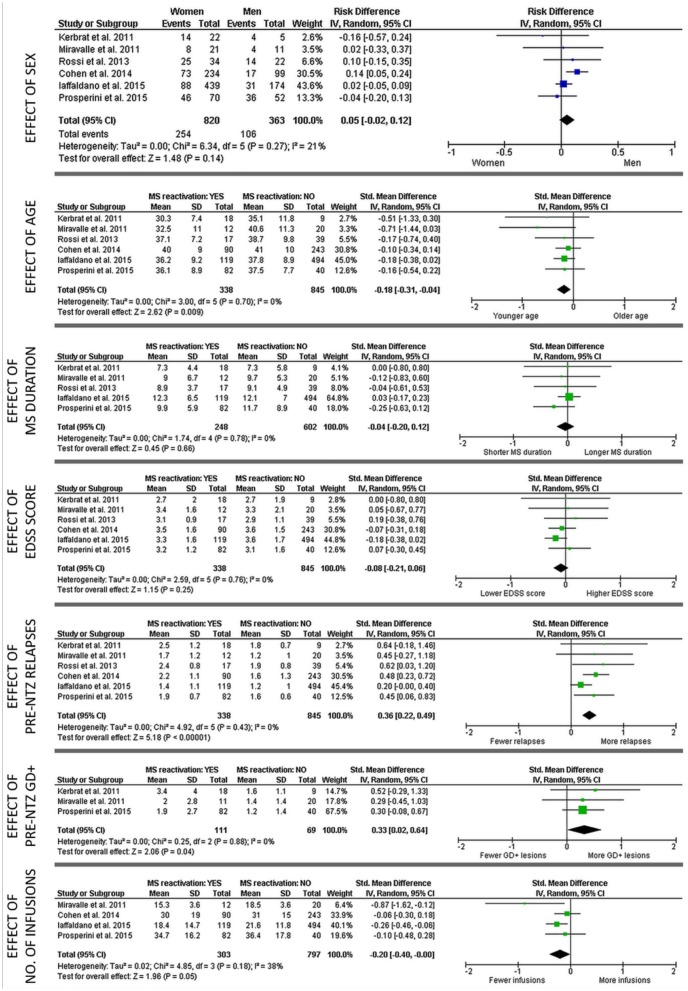

The PubMed search initially yielded 205 studies, as described earlier (Figure 1). After screening for duplication and removing duplicated data, six studies21,31,35,39,41,45 were selected for quantitative analysis, which included a total of 1183 patients with RRMS who discontinued NTZ (Table 2). The proportions of patients experiencing post-NTZ disease reactivation (defined as the occurrence of at least one clinical relapse after NTZ withdrawal and before starting another DMT) in these studies ranged from 17% to 67% at median follow-up times from 3 to 9 months.21,31,34,39,41,45 Overall, 338 (28.6%) of the 1183 patients included in the meta-analysis experienced post-NTZ disease reactivation. Forest plots summarizing the main findings of the meta-analysis are shown in Figure 2. Younger age (z = 1.48, p = 0.009), more relapses in the year prior to NTZ initiation (z = 5.18, p < 0.001), a higher number of Gd+ lesions at pre-NTZ scan (z = 2.06, p = 0.04), and fewer infusions received before treatment discontinuation (z = 1.96, p = 0.05) were associated with increased risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation. No significant study heterogeneity (I2 of 0–21%, p > 0.2) or publication bias (Egger p values of 0.10–0.68) was revealed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Sample size | Post-natalizumab disease reactivation |

Washout median (months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||

| Kerbrat et al.45 | 27 | 18 | 67 | ~6 |

| Miravalle et al.31 | 32 | 12 | 38 | ~4 |

| Rossi et al.34 | 56* | 39 | 70 | ~6 |

| Cohen et al.41 | 333 | 90 | 27 | ~4 |

| Iaffaldano et al.21 | 613 | 119 | 19 | ~3 |

| Prosperini et al.39 | 122* | 82 | 67 | ~9 |

Subgroup of patients who discontinued natalizumab.

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing main results of the meta-analysis on six articles.21,31,35,39,41,45

The study by Cohen et al.,41 Iaffaldano et al.21 Kerbrat et al.,45 and Rossi et al.35 were not included in all subanalyses given lack of data on disease duration41 and Gd+ lesions21,35,41 at natalizumab start, and number of natalizumab infusions before interruption.35,45

CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; MS: multiple sclerosis; SD: standard deviation.

Discussion

The present systematic review has the major objective of better understanding the available clinical evidence regarding the risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation. NTZ is most commonly discontinued for a perceived or real risk of PML, although several other reasons were cited in the literature, including pregnancy, patient choice, and even treatment failure.

Although NTZ is efficacious and well tolerated, it is recommended that NTZ treatment should be continued in patients at higher risk of developing PML only if benefits outweigh the risks. However, there is presently no approved strategy for circumventing disease reactivation following discontinuation of NTZ.

In this context, there is a need for greater lexical clarity and consistency, with multiple terms having been used in the literature to define post-NTZ disease activity reactivation, including ‘recurrence of disease activity’, ‘immune reconstitution syndrome’, and ‘rebound’. The term ‘recurrence of disease activity’ seems to be generic, because this phenomenon has been described even after pregnancy54 or suspension of other DMTs, such as interferon beta and fingolimod.55–58 The term ‘immune reconstitution syndrome’ generally refers to the overwhelming inflammatory reaction occurring as a result of the reconstitution of the immune system in a previously immunocompromised patient,59 but in the context of multiple sclerosis this term has been used to indicate exaggerated disease reactivation following NTZ interruption and/or forced NTZ removal by plasma exchange.60

In general, the term ‘rebound’ has been defined as ‘recurrence of symptoms of the original disorder after discontinuation of the drug; the symptoms are of equal or greater intensity to those occurring before the start of the drug treatment’.61 In the context of MS treatment there is no shared definition for rebound and only few articles provided a mixed description of this phenomenon.20,38,45,50

Therefore, this term does not seem adequate for several reasons: (i) its application is closely dependent on the baseline characteristics of patients, as patients starting NTZ with lower levels of disease activity are paradoxically more likely to be defined as having rebound48; (ii) rebound-like phenomena have also been reported after discontinuation of fingolimod56–58 and may be better defined in a qualitative manner (e.g. as the occurrence of tumefactive or tumor-like lesion following DMT discontinuation) rather than a quantitative one; and (iii) the possibility of a rebound phenomenon after NTZ discontinuation was not supported by a post hoc analysis including also data from patients originally treated with placebo.26

A total of 35 studies were selected from a PubMed search for inclusion herein. Overall, these studies showed substantial heterogeneity in sample sizes, study designs, discontinuation protocols, criteria for disease reactivation, and duration of follow up. Such heterogeneity, together with potential reporting bias, are the most important limitation of the present work, even if meta-analyzed studies showed no statistical heterogeneity and no publication bias.

In summary, radiological reactivation was experienced by 7–87% of patients commonly at 6–12 weeks after NTZ discontinuation,28 often prior to the onset of any associated clinical reactivation, which occurred in 9–80% of patients and peaked at approximately 4–7 months after the last infusion.13,27 Starting an alternative high-efficacy DMT within 2–4 months from NTZ discontinuation could mitigate this risk.17,18,21,38,41,43,48,50

This timing is consistent with the reversal of the pharmacodynamic effects of NTZ; decline in peripheral immune cells and other markers starts 8–12 weeks after discontinuation, with levels reaching those expected in untreated patients around 16 weeks post-discontinuation.62

The timing of the pharmacodynamic reversibility of NTZ should be considered when initiating an alternative therapy. Indeed, there are no established protocols for timing and choice of next DMT in patients who interrupt NTZ therapy, which was reflected in the wide range of therapies, timing, and duration of interruption in the studies included.

Disease control is often incomplete in patients receiving alternative therapies after NTZ discontinuation. The RESTORE trial provides class II evidence that NTZ interruption in relapse-free patients increases the risk of relapses and MRI activity even if an alternative DMT, namely interferon beta-1a, glatiramer acetate, and steroids, is started immediately after NTZ cessation.13 These results are consistent with another multicenter Italian study providing class III evidence of an increased risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation40 and other, smaller observational and retrospective analyses in which treatment interruption led to recurrence of clinical and MRI activity despite alternative DMT or steroid administration.

Considering the known efficacy of fingolimod, some authors have studied it as an alternative DMT in patients discontinuing NTZ.41,43,63 One large retrospective study reported that fingolimod has superior efficacy to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate,21 and several studies reported that in patients with RRMS switching from NTZ to fingolimod, shorter NTZ washout periods are associated with less MRI activity.43,63 However, a recent retrospective cohort study of 256 patients discontinuing NTZ because of anti-JCV antibodies reported that rituximab is superior to fingolimod in prolonging the beneficial effect of NTZ after its discontinuation.22 Moreover, some authors have also suggested switching from NTZ to alemtuzumab to reduce the risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation.64 Still, it may be difficult to determine if other monoclonal antibodies actually reduce the risk of developing PML in high-risk patients, given the low event rate for PML even among those patients with all three risk factors described above.24,25 Given the small number of studies looking at post-NTZ therapies and their short follow up, the risk of developing PML not only with monoclonal antibodies, but also with small molecules such as fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate, is still uncertain.

Regarding predictors of disease activity in patients discontinuation NTZ, our meta-analysis of six studies involving 1183 patients with RRMS confirms that post-NTZ disease reactivation (defined as the occurrence of at least one relapse) is associated with certain patient characteristics at NTZ start (younger age), pre-NTZ level of disease activity (higher number of relapses and Gd+ lesions), and shorter duration of treatment. An insufficient number of studies investigated the risk of post-NTZ disability worsening for performing a meta-analysis on this outcome to be possible. However, it is noteworthy that older age, higher EDSS score, and EDSS worsening while on NTZ have been reported as risk factors for both short-term and long-term post-NTZ disability worsening.39,53

Some conclusions can be reached on the basis of the available evidence. First, NTZ discontinuation should be avoided to maintain effectiveness in disease suppression, when possible (e.g. anti-JCV antibody-negative serostatus).65 Second, patients at lower risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation usually were older, experienced fewer relapses and lower MRI activity before starting NTZ, and received more infusions. If a patient requires discontinuation from NTZ, risk profiling can help predict patients at greater risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation. Third, we strongly recommended the use of the term ‘post-NTZ disease reactivation’ and suggest avoiding the term ‘rebound’ to merely indicate severe relapses or impressive MRI activity following NTZ discontinuation, at least until consensus is reached on an objective definition. Finally, there is class II/III evidence that interferon beta formulations, glatiramer acetate, and steroids do not provide adequate disease control following NTZ discontinuation.13,40

We hope the findings from this meta-analysis help clinicians identify patients who are at greater risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation and therefore might be considered for switching to high efficacy DMTs22,24,64 after a careful screening for subclinical PML or any other comorbid condition that could be aggravated by other DMTs. Based on the pharmacodynamic effect of NTZ, the next DMT should be started preferably within 8 weeks from NTZ interruption, because longer washout duration are reported to be associated with higher risk for disease reactivation.17,18,21,38,41,43,48 In addition, the results from the RESTORE study13 suggest that continuing MRI surveillance as late as 12–16 weeks after the last infusion may further facilitate identification of patients at future risk of post-NTZ disease reactivation. However, given the limitations of our work, mainly due to between study variability and potential reporting bias, further efforts are warranted to provide evidence on how to manage NTZ discontinuation.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_1 for Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis by Luca Prosperini, Revere P. Kinkel, Augusto A. Miravalle, Pietro Iaffaldano and Simone Fantaccini in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_2 for Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis by Luca Prosperini, Revere P. Kinkel, Augusto A. Miravalle, Pietro Iaffaldano and Simone Fantaccini in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders

Acknowledgments

Alison Adams, PhD, and Joshua Safran of Ashfield Healthcare Communications (Middletown, CT, USA), through funding from Biogen, provided editorial support for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported by Biogen. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

Conflict of interest statement: LP has received research grant from Genzyme and Italian MS Society (Associazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla); consulting fees from Biogen, Genzyme, and Novartis; speaking honoraria from Almirall, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche and Teva; and travel grants from Biogen, Genzyme, and Teva. He is also a member of the steering committee AIFA (Italian Medicine Agency) on natalizumab. RPK has been a scientific consultant for CorTech, Genentech, ImStem, and Novoron and has received speaking honoraria from Acorda, Biogen, Genentech, and Genzyme. AAM has received consulting fees from Bayer, Biogen, the Consortium of MS Centers, Genentech, Genzyme, Questcor/Mallinckrodt, and the Rocky Mountain MS Center. PI has received consulting fees from Bayer-Schering, Biogen, and Genzyme; speaking honoraria from Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva; and travel grants from Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva. SF had equity interests in Biogen and was employeed by Biogen at the time of manuscript development.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Luca Prosperini, Department of Neurosciences, S. Camillo-Forlanini Hospital, Circonvallazione Gianicolense, 87, 00152 Rome, Italy.

Revere P. Kinkel, Department of Neurosciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

Augusto A. Miravalle, Advanced Neurology of Colorado, MS Center of the Rockies, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO, USA

Pietro Iaffaldano, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neurosciences and Sense Organs, University of Bari ‘Aldo Moro’, Bari, Italy.

Simone Fantaccini, Biogen Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy.

References

- 1. Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudick RA, Stuart WH, Calabresi PA, et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 911–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Connor P, Goodman A, Kappos L, et al. Long-term safety and effectiveness of natalizumab redosing and treatment in the STRATA MS study. Neurology 2014; 83: 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1870–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bozic C, Richman S, Plavina T, et al. Anti-John Cunningham virus antibody prevalence in multiple sclerosis patients: baseline results of STRATIFY-1. Ann Neurol 2011; 70: 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gorelik L, Lerner M, Bixler S, et al. Anti-JC virus antibodies: implications for PML risk stratification. Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, et al. Anti-JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 2014; 76: 802–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sorensen PS, Bertolotto A, Edan G, et al. Risk stratification for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with natalizumab. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ho P-R, Koendgen H, Campbell N, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective analysis of data from four clinical studies. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwab N, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Hoyt T, et al. Anti-JCV serology during natalizumab treatment: review and meta-analysis of 17 independent patient cohorts analyzing anti-John Cunningham polyoma virus sero-conversion rates under natalizumab treatment and differences between technical and biological sero-converters. Mult Scler 2018; 24: 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegen H, Auer M, Bsteh G, et al. Stability and predictive value of anti-JCV antibody index in multiple sclerosis: a 6-year longitudinal study. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0174005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Medicines Agency. Updated recommendations to minimise the risk of the rare brain infection PML with Tysabri, http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2016/02/news_detail_002471.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1 (accessed 8 March 2018).

- 13. Fox RJ, Cree BA, De Seze J, et al. MS disease activity in RESTORE: a randomized 24-week natalizumab treatment interruption study. Neurology 2014; 82: 1491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magraner MJ, Coret F, Navarre A, et al. Pulsed steroids followed by glatiramer acetate to prevent inflammatory activity after cessation of natalizumab therapy: a prospective, 6-month observational study. J Neurol 2011; 258: 1805–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borriello G, Prosperini L, Mancinelli C, et al. Pulse monthly steroids during an elective interruption of natalizumab: a post-marketing study. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rinaldi F, Seppi D, Calabrese M, et al. Switching therapy from natalizumab to fingolimod in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 1640–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Havla J, Tackenberg B, Hellwig K, et al. Fingolimod reduces recurrence of disease activity after natalizumab withdrawal in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2013; 260: 1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jokubaitis VG, Li V, Kalincik T, et al. Fingolimod after natalizumab and the risk of short-term relapse. Neurology 2014; 82: 1204–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rossi S, Motta C, Studer V, et al. Treatment options to reduce disease activity after natalizumab: paradoxical effects of corticosteroids. CNS Neurosci Ther 2014; 20: 748–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Capobianco M, di Sapio A, Malentacchi M, et al. No impact of current therapeutic strategies on disease reactivation after natalizumab discontinuation: a comparative analysis of different approaches during the first year of natalizumab discontinuation. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22: 585–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Pozzilli C, et al. Fingolimod versus interferon beta/glatiramer acetate after natalizumab suspension in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2015; 138: 3275–3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 2016; 79: 950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wattjes MP, Killestein J. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab discontinuation: few and true? Ann Neurol 2014; 75: 462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giovannoni G, Marta M, Davis A, et al. Switching patients at high risk of PML from natalizumab to another disease-modifying therapy. Pract Neurol 2016; 16: 389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marignier R, Durand-Dubief F, du Pasquier R, et al. Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis: also consider progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy risk. Ann Neurol 2016; 80: 791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O’Connor PW, Goodman A, Kappos L, et al. Disease activity return during natalizumab treatment interruption in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2011; 76: 1858–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sangalli F, Moiola L, Ferre L, et al. Long-term management of natalizumab discontinuation in a large monocentric cohort of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014; 3: 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grimaldi LM, Prosperini L, Vitello G, et al. MRI-based analysis of the natalizumab therapeutic window in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 1337–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. ; the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. West TW, Cree BA. Natalizumab dosage suspension: are we helping or hurting? Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miravalle A, Jensen R, Kinkel RP. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosis following cessation of natalizumab therapy. Arch Neurol 2011; 68: 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borriello G, Prosperini L, Marinelli F, et al. Observations during an elective interruption of natalizumab treatment: a post-marketing study. Mult Scler 2011; 17: 372–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Havla J, Gerdes LA, Meinl I, et al. De-escalation from natalizumab in multiple sclerosis: recurrence of disease activity despite switching to glatiramer acetate. J Neurol 2011; 258: 1665–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossi S, Motta C, Studer V, et al. Effect of glatiramer acetate on disease reactivation in MS patients discontinuing natalizumab. Eur J Neurol 2013; 20: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rossi S, Motta C, Studer V, et al. A genetic variant of the anti-apoptotic protein Akt predicts natalizumab-induced lymphocytosis and post-natalizumab multiple sclerosis reactivation. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoepner R, Havla J, Eienbröker C, et al. Predictors for multiple sclerosis relapses after switching from natalizumab to fingolimod. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 1714–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferré L, Moiola L, Sangalli F, et al. Recurrence of disease activity after repeated Natalizumab withdrawals. Neurol Sci 2015; 36: 465–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lo Re M, Capobianco M, Ragonese P, et al. Natalizumab discontinuation and treatment strategies in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS): a retrospective study from two Italian MS centers. Neurol Ther 2015; 4: 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prosperini L, Annovazzi P, Capobianco M, et al. Natalizumab discontinuation in patients with multiple sclerosis: profiling risk and benefits at therapeutic crossroads. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clerico M, Schiavetti I, De Mercanti SF, et al. Treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis after 24 doses of natalizumab: evidence from an Italian spontaneous, prospective, and observational study (the TY-STOP Study). JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 954–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cohen M, Maillart E, Tourbah A, et al. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: a French prospective study. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 436–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gobbi C, Meier DS, Cotton F, et al. Interferon beta 1b following natalizumab discontinuation: one year, randomized, prospective, pilot trial. BMC Neurol 2013; 13: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kappos L, Radue EW, Comi G, et al. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in RRMS. Neurology 2015; 85: 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaufman M, Cree BA, De Sèze J, et al. Radiologic MS disease activity during natalizumab treatment interruption: findings from RESTORE. J Neurol 2015; 262: 326–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kerbrat A, Le Page E, Leray E, et al. Natalizumab and drug holiday in clinical practice: an observational study in very active relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci 2011; 308: 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Killestein J, Vennegoor A, Strijbis EM, et al. Natalizumab drug holiday in multiple sclerosis: poorly tolerated. Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Melis M, Cocco E, Frau J, et al. Post-natalizumab clinical and radiological findings in a cohort of multiple sclerosis patients: 12-month follow-up. Neurol Sci 2014; 35: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Salhofer-Polanyi S, Baumgartner A, Kraus J, et al. What to expect after natalizumab cessation in a real-life setting. Acta Neurol Scand 2014; 130: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sempere AP, Martín-Medina P, Berenguer-Ruiz L, et al. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: an observational study. Acta Neurol Scand 2013; 128: e6–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sorensen PS, Koch-Henriksen N, Petersen T, et al. Recurrence or rebound of clinical relapses after discontinuation of natalizumab therapy in highly active MS patients. J Neurol 2014; 261: 1170–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stuve O, Cravens PD, Frohman EM, et al. Immunologic, clinical, and radiologic status 14 months after cessation of natalizumab therapy. Neurology 2009; 72: 396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vellinga MM, Castelijns JA, Barkhof F, et al. Post-withdrawal rebound increase in T2 lesional activity in natalizumab-treated MS patients. Neurology 2008; 70: 1150–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vidal-Jordana A, Tintore M, Tur C, et al. Significant clinical worsening after natalizumab withdrawal: predictive factors. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, et al. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Siger M, Durko A, Nicpan A, et al. Discontinuation of interferon beta therapy in multiple sclerosis patients with high pre-treatment disease activity leads to prompt return to previous disease activity. J Neurol Sci 2011; 303: 50–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berger B, Baumgartner A, Rauer S, et al. Severe disease reactivation in four patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis after fingolimod cessation. J Neuroimmunol 2015; 282: 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Faissner S, Hoepner R, Lukas C, et al. Tumefactive multiple sclerosis lesions in two patients after cessation of fingolimod treatment. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2015; 8: 233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hatcher SE, Waubant E, Nourbakhsh B, et al. Rebound syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosis after cessation of fingolimod treatment. JAMA Neurol 2016; 73: 790–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tan IL, McArthur JC, Clifford DB, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in natalizumab-associated PML. Neurology 2011; 77: 1061–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Scarpazza C, Prosperini L, De Rossi N, et al. ; Italian PML group. To do or not to do? Plasma exchange and timing of steroid administration in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 2017; 82: 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Leonard BE. Fundamentals of Psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, England; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Plavina T, Muralidharan KK, Kuesters G, et al. Reversibility of the effects of natalizumab on peripheral immune cell dynamics in MS patients. Neurology 2017; 89: 1584–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Comi G, Gold R, Dahlke F, et al. Relapses in patients treated with fingolimod after previous exposure to natalizumab. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 786–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Malucchi S, Capobianco M, Lo Re M, et al. High-Risk PML Patients Switching from Natalizumab to Alemtuzumab: an Observational Study. Neurol Ther 2017; 6: 145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sormani MP, De Stefano N. Natalizumab discontinuation in the increasing complexity of multiple sclerosis therapy. Neurology 2014; 82: 1484–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_1 for Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis by Luca Prosperini, Revere P. Kinkel, Augusto A. Miravalle, Pietro Iaffaldano and Simone Fantaccini in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders

Supplemental material, Supplementary_File_2 for Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis by Luca Prosperini, Revere P. Kinkel, Augusto A. Miravalle, Pietro Iaffaldano and Simone Fantaccini in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders