Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is becoming increasingly established as a stand-alone procedure for weight reduction. The restrictive as well as humoral characteristics of this operation assure postoperative weight loss of up to 70–80% after 1 year. Complications also occur with this procedure.

Methods

The technical details of the sleeve gastrectomy surgical procedure are described, while elaborating on potential complications and on calibration. In our case, we perform gastrectomy under intraoperative gastroscopic control for calibration as well as for suture control as a standard procedure. As a general practice, the staple line is reinforced with the bioabsorbable material Seamguard®.

Results

Since June 2006, 38 patients have undergone sleeve gastrectomy. Postsurgical bleeding occurred in 1 case (2.6%) and had to be treated surgically.1 patient developed cicatricial stenosis and required dilatation (2.6%). After 1 year, 85% of patients had a weight loss of 70–80%.

Conclusion

Thanks to the standardisation of this procedure using staple line reinforcement and intraoperative gastroscopic control, the complication rate can be reduced and the successful outcome of this stand-alone, weight-reduction operation can beoptimised.

Key Words: Morbid obesity, Bariatric surgery, Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Gastroscopy

Introduction

For some 7 years now laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has been performed as the first step of a 2-stage operation in cases of extreme obesity and high operative risk in order to reduce the high complication rate, which can be as high as 38% in the presence of a BMI < 65 kg/m2 or when performing biliopancreatic diversion or duodenal switch [1–7]. This can assure a weight loss of up to 70% and markedly reduce the operative risk. Thanks to encouraging data, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has become more and more widespread in recent years, is also carried out as a stand-alone, weight-reduction procedure in cases of extreme obesity, and is now also being used in patients with a BMI < 40 kg/m2 as a restrictive procedure instead of gastric banding or gastric bypass which had been commonly used hitherto [3, 8–13]. This is not least due to the fact that, apart from the restrictive component, humoral changes also contribute to a loss of appetite with fewer hunger pangs at least during the initial months. If this surgical technique is aspired as a stand-alone procedure, a plethora of technical details must be taken into account to assure good long-term weight loss which, in the ideal case, is on a par with that achieved by gastric bypass surgery. One of the chief determinants in this respect is the bougie diameter [3, 13–15]. Secondary dilatation of the tubular stomach tends to be warranted here only in exceptional cases [16]. There are also variations in regard to where gastrectomy is initiated in the region of the antrum and its distance vis-à-vis the pylorus in order to avoid impairment of the pylorus functions. Assuring resection of a fundus volume as extensive as possible is also important while ensuring that there is no injury to the oesophagus [3, 8]. To avoid bleeding and leakage, suture reinforcement is often used and/or the staple line is fully oversewn, or this is done at least at the intersections [3, 7, 11, 17–20]. On the basis of these experiences and recommendations, we have been developing our technical concept of sleeve gastrectomy since 2006.

Material and Methods

The patient is placed with their legs spread out on the operating table. The surgeon stands between the patient's legs, with the first assistant on the patient's left side and the second assistant on the right. First of all, a minilaparotomy is performed above the navel in the upper abdomen for placement of a 10 mm Hasson trocar for the optics. After generation of the pneumoperitoneum with a pressure value of up to 15 mm Hg, two further 12 mm trocars are placed under optical control in the right and left upper abdomen, two 5 mm trocars in the left upper abdomen as well as below the xiphoid. Depending on the overview, two additional trocars are placed, if necessary. The pneumoperitoneum pressure is around 15 mm Hg and can be increased if required.

The patient is moved to an anti-Trendelenburg position. Then the greater omentum is opened along the greater curvature with the ultrasonic dissector (Ultracision®; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, a Johnson & Johnson Company, Norderstedt, Germany). Gastrectomy is commenced around 4–6 cm proximal to the pylorus. Dissection is continued proximally close to the gastric wall, and the short gastric vessels are dissected while ensuring meticulous haemostasis (fig. 1). The greater curvature of the stomach is mobilised as far as the gastroeosophageal junction and the dorsal adhesions are likewise dissected with the ultrasonic dissector. For calibration of the stomach, a gastroscope is then inserted along the smaller curvature (diameter 9 mm) and advanced as far as the duodenum in order to determine the gastrectomy limits (fig. 2). The stomach is then completely suctioned off using the gastric tube. Finally, gastrectomy is performed along the gastroscope using an endoscopic stapler (Echelon®; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, a Johnson & Johnson Company, Norderstedt, Germany) (fig. 3). Green stapler magazines are used for the antrum, body of the stomach, and cardiac part. Based on our experiences, these provide for good closure of the staple line. A gold-coloured stapler magazine is used for the fundus region, where it assures a greater degree of safety. Reinforcement of the staple line with a bioabsorbable material (Seamgard®; WL Gore, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) has proved useful for ensuring bloodless gastrectomy. This provides for a completely bloodless gastrectomy. However, in the critical region of the fundus we dispensed with this reinforcement, as there are some reports of an increased risk of suture insufficiency when using additional staple line reinforcement here. The gastric tube is removed before commencement of gastrectomy to avoid crossover of the staple line. Gastrectomy is performed proximally along the gastroscope, using overlapping staple lines. Gastrectomy is conducted in the fundus region in the direction of the left diaphragmatic crus, while avoiding injury to the oesophagus. The staple line is examined for leakage and bleeding sources, in particular at intersection points. Continuous sewing using an endoclip suture is then carried out for reinforcement, with the suture being fitted with a clip after each stitch to assure enhanced reinforcement (fig. 4). Once suturing has been completed, the gastroscope is withdrawn under optical control from the tubular stomach. Therefore, the patient is removed from the anti-Trendelenburg position. An irrigation liquid is applied to the central upper abdomen. This allows for endoluminal inspection for any bleeding sources in the region of the mucosa and along the gastrectomy line. Furthermore, after retraction of the antrum distally to the resection line and filling the stomach with air, any leakages in the resection sutures will be detected at an early stage. The irrigation fluid is then suctioned off.

The resected stomach volume is removed through the opening made in the upper abdomen at the time of minilaparatomy. A Robinson drain is inserted on the left side. The trocars are removed under optical control. The fasciae are closed with Vicryl® (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, a Johnson & Johnson Company, Norderstedt, Germany) single-button sutures in the region of the minilaparatomy. The skin is closed with a staple line.

Before normal food intake, the suture is examined radiologically, using contrast media in the stomach. Until then, the patient is given parenteral nutrition; the drain is removed after radiological examination.

Perioperative and Postoperative Results

38 patients suffering from morbid obesity with an average BMI of 51 kg/m2 (35–81 kg/m2) have to date been operated on using this technique. No surgical complications occurred intraoperatively. Suture insufficiency was not seen in any of the patients (0%), nor did any postoperative surgical infections or impaired wound healing occur (0%). 1 patient had to undergo relaparoscopy because of postsurgical bleeding, but at that time there was no longer an active bleeding source (2.6%). 1 patient suffered from relevant postsurgical cicatricial stenosis which required dilatation under gastroscopy (2.6%). After 6 months, excess weight loss (EWL) of an average of 50–60% was achieved in 85% (n = 32) of the patients by using this technique, and an average of 70–80% after 1 year. In some cases of the remaining patients with weight loss of around 20% after 6 months, it was necessary to remove a gastric band before sleeve gastrectomy because of complications. As such, this already resulted in presurgical weight loss. However, in some cases no sufficient weight loss could be achieved due to dietary mistakes such as sweet eating or consumption of high-calorie drinks or alcohol.

Discussion

There are a number of technical measures that can be taken to minimise intra- and postoperative complications of sleeve gastrectomy. Firstly, impaired emptying of the stomach as well as the risk of suture insufficiency in the antrum region can be minimised by observing a sufficiently long distance from the pylorus as well as ensuring a sufficiently long staple line [3, 6, 8, 10, 17]. In general, placement of a bougie for calibration of the residual stomach is deemed obligatory [3]. However, the bougie diameter needed is still the subject of controversial discussion [1, 3, 7, 10, 11, 13–15]. Proponents of narrow sleeve gastrectomy set this at between 32 and a maximum of 42 French. For this, we use a gastroscope (9–10 mm diameter) that can be adequately accommodated on the lesser curvature side as far as the duodenum in order to, firstly, assure adequate gastrectomy and, secondly, to preoperatively preclude stenoses. In our 1 case of postoperative stenosis the gastroscope had already been removed before oversewing the staple line, thus increasing the risk of stenosis in the region of the angular fold. Based on our experiences and on the data available in the literature, staple line reinforcement with Seamguard® (W.L. Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) is a suitable method for minimising bleeding from the staple line [3, 17, 18, 20]. Whether oversewing is additionally needed is a matter of discussion [3, 7, 19]. However, in order to prevent bleeding several surgeons oversew at least overlapping regions of the staple line, which constitute a weak point.

As far as can be judged from the literature, most instances of suture insufficiency are found in the region of the fundus. Hence it is important, on the one hand, to assure sufficient mobilisation of this region without minimising bleeding, but on the other hand, it is precisely here that the staple line has to be securely closed. This has to be done under optimal visual control. Whether staple line reinforcement can be dispensed with here is also a matter of controversy, since in some cases it is thought to be the cause of suture insufficiency. Despite these problem issues relating to the apical region of the stomach, providing for resection of an adequate fundus volume is the chief determinant of postoperative weight loss as this does not only serve as a mechanical impediment to food intake but also means that a large section of the ghrelin-producing cells will be removed so as to markedly reduce hungry pangs.

On completion of gastrectomy and suturing, we believe that gastroscopy with air insufflation and optical control for bleeding sources represents a suitable procedure for intraoperative suture control.

Adequate gastrectomy is confirmed by our postoperative results with an average weight loss of 70% after 1 year, which are on a par with those in the literature [1, 3, 8].

Conclusion

Both our peri- and postoperative results attest to good standardisation of the sleeve gastrectomy surgical procedure compared with the literature. It serves to minimise complications and, as borne out by our results, provides for sufficient resection of the stomach. Staple line reinforcement with Seamguard appears to reduce the risk of bleeding. Placement of a gastroscope, serving as a bougie for calibration as well as for suture control at the end of the operation, has proved useful in minimising complications.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

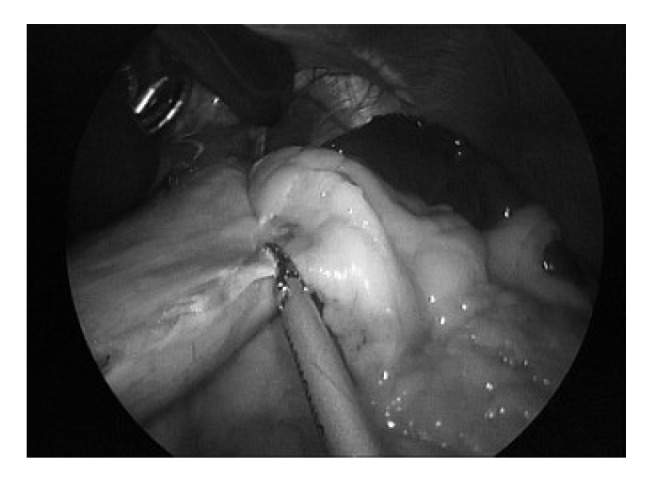

Fig. 1.

Mobilisation of the stomach with dissection of the short gastric vessels with the ultrasonic dissector.

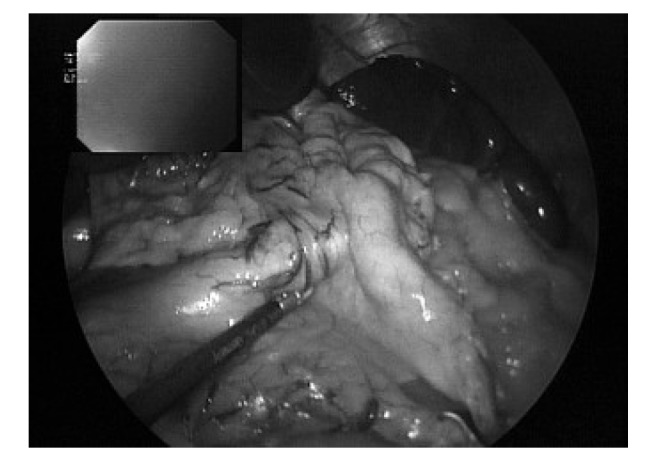

Fig. 2.

Placement of a gastroscope for determination of gastrectomy limits and gastric visualisation during gastrectomy and oversewing.

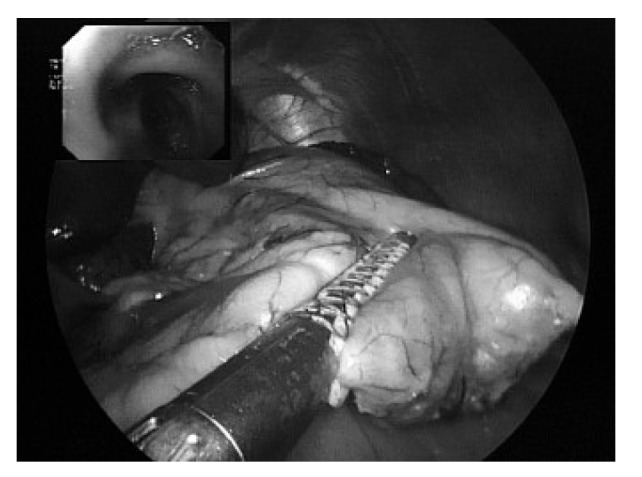

Fig. 3.

Dissection of the gastric wall with the stapler device. In addition, staple line reinforcement (Seamguard) is used.

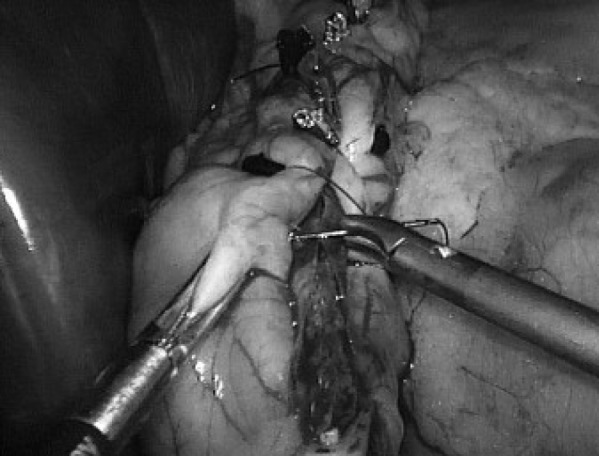

Fig. 4.

Final oversewing of the entire staple line with continuous Endoclip suture.

References

- 1.Aggarwal S, Kini SU, Herron DM. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: a review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottam D, Qureshi FG, Mattar SG, Sharma S, Holover S, Bonanomi G, Ramanathan R, Schauer P. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial weight-loss procedure for high-risk patients with morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:859–863. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deitel M, Crosby RD, Gagner M. The first international consensus summit for sleeve gastrectomy, New York City, October 25–27, 2007. Obes Surg. 2008;18:487–496. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ianelli A, Dainese R, Piche T, Facchiano E, Gugenheim J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:821–827. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lalor PF, Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milone L, Strong V, Gagner M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is superior to endoscopic intragastric balloon as a first stage procedure for super-obese patients (BMI = 50) Obes Surg. 2005;15:612–617. doi: 10.1381/0960892053923833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moy J, Pomp A, Dakin G, Parikh M, Gagner M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Am J Surg. 2008;196:e56–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumbs A, Gagner M, Dakin G, Pomp A. Sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2007;17:962–969. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kueper MA, Kramer KM, Kirschniak A, Königsrainer A, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: standardized technique of a potential stand-alone bariatric procedure in morbidly obese patients. World J Surg. 2008;32:1462–1465. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roa PE, Kaidar-Person O, Pinto D, Cho M, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ, Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as treatment for morbid obesity. technique and short-term outcome. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1323–1326. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skrekas G, Lapatsanis D, Stafyla V, Papalambros A. One year after laparoscopic 'tight' sleeve gastrectomy: technique and outcome. Obes Surg. 2008;18:810–813. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9440-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Indications for sleeve gastrectomy as a primary procedure for weight loss in the morbidly obese. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:662–667. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner R, Weiner S, Pomhoff I, Jacobi C, Makarewicz W, Weigand G. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy - influence of sleeve size and resected gastric volume. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1297–1305. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akkary E, Duffy A, Bell R. Deciphering the sleeve: technique, indications, efficacy, and safety of sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1323–1329. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh M, Gagner M, Heacock L, Strain G, Dakin G, Pomp A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: does bougie size affect mean % EWL? Short-term outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:528–533. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer FB, Bohdjalian A, Felberbauer FX, Fleischmann E, Reza Hoda MA, Ludvik B, Zacherl J, Jakesz R, Prager G. Does gastric dilation limit the success of sleeve gastrectomy as a sole operation for morbid obesity? Obes Surg. 2006;16:166–171. doi: 10.1381/096089206775565276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, Brady R, Vroegop T, Serveld M. The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1290–1298. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consten EC, Gagner M, Pomp A, Inabet WB. Decreased bleeding after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with or without duodenal switch for morbid obesity using a stapled buttressed absorbable polymer membrane. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1360–1266. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasalicky M, Michalsky D, Housova J, Haluzik M, Housa D, Haluzikova D, Fried M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy without an over-sewing of the staple line. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1257–1262. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9635-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen NT, Longoria M, Chalifoux S, Wilson SE. Bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement for laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgery. Surg Technol Int. 2005;14:107–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]