Abstract

Rationale: BMP9 (bone morphogenetic protein 9) is a circulating endothelial quiescence factor with protective effects in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Loss-of-function mutations in BMP9, its receptors, and downstream effectors have been reported in heritable PAH.

Objectives: To determine how an acquired deficiency of BMP9 signaling might contribute to PAH.

Methods: Plasma levels of BMP9 and antagonist soluble endoglin were measured in group 1 PAH, group 2 and 3 pulmonary hypertension (PH), and in patients with severe liver disease without PAH.

Measurements and Main Results: BMP9 levels were markedly lower in portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH) versus healthy control subjects, or other etiologies of PAH or PH; distinguished PoPH from patients with liver disease without PAH; and were an independent predictor of transplant-free survival. BMP9 levels were decreased in mice with PH associated with CCl4-induced portal hypertension and liver cirrhosis, but were normal in other rodent models of PH. Administration of ALK1-Fc, a BMP9 ligand trap consisting of the activin receptor-like kinase-1 extracellular domain, exacerbated PH and pulmonary vascular remodeling in mice treated with hypoxia versus hypoxia alone.

Conclusions: BMP9 is a sensitive and specific biomarker of PoPH, predicting transplant-free survival and the presence of PAH in liver disease. In rodent models, acquired deficiency of BMP9 signaling can predispose to or exacerbate PH, providing a possible mechanistic link between PoPH and heritable PAH. These findings describe a novel experimental model of severe PH that provides insight into the synergy between pulmonary vascular injury and diminished BMP9 signaling in the pathogenesis of PAH.

Keywords: bone morphogenetic protein, signaling, portopulmonary hypertension, portal hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Portopulmonary hypertension is thought to be related to other forms of pulmonary arterial hypertension, but its causative mechanisms and relationship to genetic forms of disease are unclear.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study demonstrates a previously unappreciated link between BMP9 signaling, previously implicated in genetic forms of pulmonary arterial hypertension, and portopulmonary hypertension.

The World Health Organization Classification defines group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) by a mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than or equal to 25 mm Hg, pulmonary vascular resistance greater than 3 Wood units, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure less than or equal to 15 mm Hg, in the absence of left-sided heart disease, severe lung disease, or chronic thromboembolic disease (1). Group 1 PAH includes patients with heritable PAH (HPAH); idiopathic PAH (IPAH); PAH associated with systemic conditions, including toxin or stimulant drug exposure (APAH-STIM) and connective tissue disease (APAH-CTD); and portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH) (2). Most HPAH disease is attributed to heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the BMP (bone morphogenetic protein) signaling pathway (3, 4), including mutations affecting BMPR2 encoding the BMP type II receptor (5), and ACVRL1 and ENG encoding the BMP9 receptor and coreceptor ALK1 (activin receptor-like kinase-1) and endoglin, respectively (6, 7). Homozygous nonsense mutations in BMP9, encoding the cognate ligand itself, have been reported in a child with severe PAH (8). Although the mutations implicated in HPAH are incompletely penetrant, they subtend a set of genes critical for the transduction of BMP9 by endothelial cells, supporting a pivotal contribution of this signaling axis to PAH.

The etiology of PoPH is poorly understood, and its mechanistic relationship to other etiologies of World Health Organization group I PAH is unknown. We previously reported that circulating levels of the soluble form of endoglin (sEng), an antagonist of BMP9, are a sensitive biomarker of PAH (9, 10). We recently found that exogenous BMP9 attenuates pulmonary hypertension (PH), vascular remodeling, and right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy in several animal models of PH (11), further implicating the BMP9/BMPR2/endoglin/ALK1 signaling axis in PH. Because BMP9 is present in the circulation at biologically active levels (12–15), and is synthesized by the liver, we hypothesized that altered expression of BMP9 might serve as a sensitive mechanistic biomarker of PAH associated with liver disease. In two independent cohorts of patients with diverse etiologies of PAH, we found profoundly diminished circulating BMP9 among patients with PoPH, suggesting a role of impaired signaling. Similarly, diminished BMP9 levels were found in rodents with PH associated with portal hypertension and cirrhosis, but not in other animal models of PH. Importantly, administration of the BMP9 ligand trap ALK1-Fc exacerbated PH and pulmonary vascular remodeling in mice exposed to hypoxia, directly demonstrating a protective effect of endogenous BMP9. Diminished BMP9 thus seems to be a risk factor and sensitive biomarker of PoPH. The acquired deficiency of BMP9 signaling in PoPH may provide a mechanistic link to HPAH, and could represent a clinical screening opportunity for the diagnosis and management of PoPH in high-risk populations.

Methods

Detailed materials and methods are available in the online supplement.

Results

Serum BMP9 Induces SMAD1/5/8 Phosphorylation in Endothelial Cells

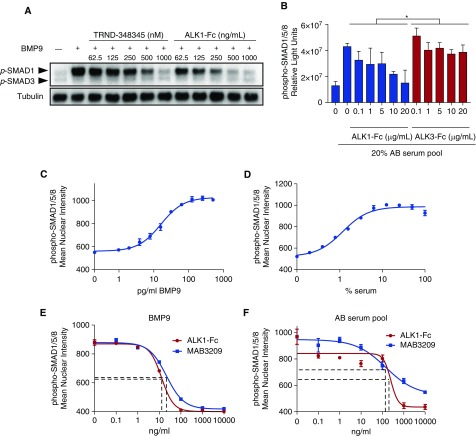

As previously described (11, 16), recombinant mature BMP9 homodimeric protein activated BMP-responsive SMAD1/5/8 potently in endothelial cells, assayed by immunoblot, in-cell Western assay, and SMAD1/5/8 nuclear translocation assays (Figure 1). BMP9-mediated activation of SMAD1 was dose-dependently inhibited by a potent ALK1/ALK2 kinase inhibitor, TRND-348345, or by the BMP9 ligand trap ALK1-Fc (Figure 1A). Exposure of cultured human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells to pooled human serum (20%) also resulted in activation of SMAD1/5/8, which was inhibited to baseline levels by ALK1-Fc, but not BMP2/4 ligand trap ALK3-Fc (Figure 1B), suggesting that BMP9 is the predominant endothelial SMAD1/5/8–activating factor in the circulation. A phospho-SMAD1/5/8 nuclear translocation assay using cultured pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (Figures 1C and 1D; see Figures E1A and E1B in the online supplement) demonstrated potent activation of endothelial signaling by BMP9 (EC50 ∼16 pg/ml) and pooled human serum (EC50 ∼1.6%). BMP9-mediated activation of endothelial SMAD1/5/8 was abrogated by cotreatment with ALK1-Fc or a monoclonal anti-BMP9 (MAB3209, Figure 1E). Serum-induced activation of endothelial SMAD1/5/8 was similarly inhibited by ALK1-Fc or anti-BMP9 (Figure 1F), accounting for 80–100% of activity, confirming that the principal endothelial SMAD1/5/8–activating factor in circulation is BMP9.

Figure 1.

BMP9 (bone morphogenetic protein 9) accounts for most serum-induced SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation in endothelial cells. (A) Western blot detecting phosphorylated forms of SMAD1 and SMAD3 in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells revealed BMP9-mediated activation of SMAD1 (1 ng/ml) is inhibited by ALK1/ALK2 kinase inhibitor TRND-348345 or BMP9 ligand trap ALK1-Fc. (B) In-cell Western revealed activation of SMAD1/5/8 after stimulation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells with human serum (20%), with inhibition of phospho-SMAD1/5/8 to baseline levels by ALK1-Fc, but not BMP2/4 ligand trap ALK3-Fc (*P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA). (C and D) High-content phospho-SMAD1/5/8 nuclear translocation assay revealed activation of endothelial signaling by BMP9 (EC50 ∼16 pg/ml) and pooled human AB serum (EC50 ∼1.6%) in cultured pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. (E and F) BMP9-mediated or serum-induced activation of endothelial SMAD1/5/8 was abrogated by cotreatment with ALK1-Fc or a monoclonal anti-BMP9 Ab.

To detect BMP9 in plasma and serum, a sandwich ELISA with a sensitivity of approximately 1.6 pg/ml for recombinant mature BMP9 and no cross-reactivity for highly homologous BMP10 was used (see Figure E1C). Specificity was confirmed by the observation that 100% of BMP9 could be neutralized by exogenous ALK1-Fc (see Figure E1D) in a dose-dependent fashion (IC50 ∼14 ng/ml), and similarly for BMP9 activity in normal human and mouse plasma (see Figure E1E). To ascertain the protein species measured by this antibody pair, an immunoprecipitation reaction using the capture antibody (MAB3209) with pooled human serum was resolved by immunoblot using the detection antibody (BAF3209). Under reducing conditions, the predicted 12.5-kD BMP9 monomer was visualized with the immunoprecipitation of human serum with MAB3209 but not control IgG, consistent with the monomer from reduced recombinant mature human BMP9 (see Figure E1F).

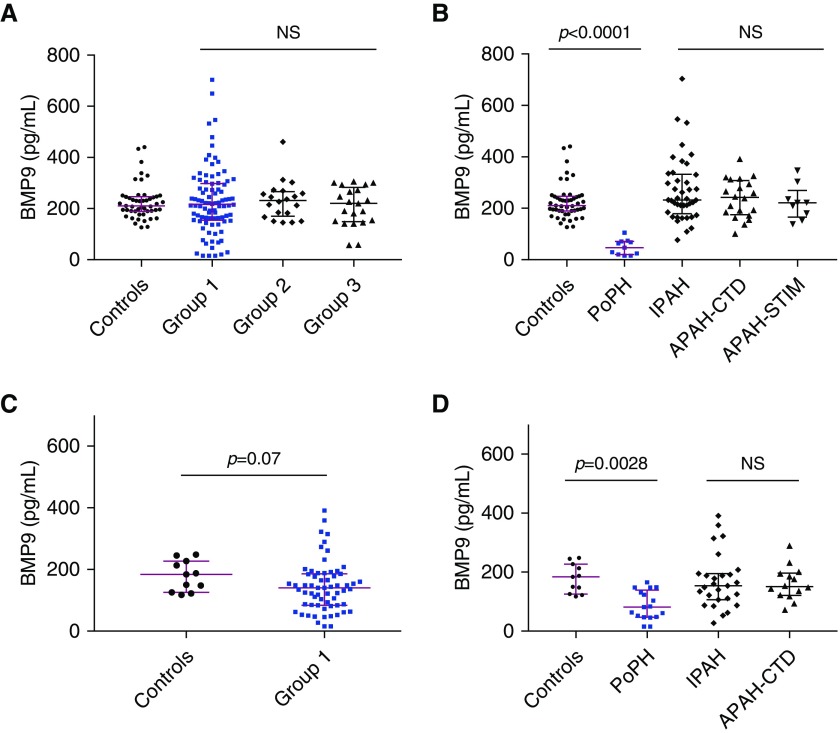

Circulating BMP9 Is Diminished in PoPH but Not Other Etiologies of Group 1 PAH

Levels of circulating BMP9 were measured in distinct derivation and validation cohorts of group 1 PAH, as well as patients with group 2 and 3 PH, with baseline demographic and clinical data presented in Tables 1 and 2. BMP9 levels in healthy individuals were comparable with previously reported average concentrations (17). Within the derivation cohort (Figure 2A), there was no significant difference in circulating BMP9 between healthy volunteers and patients with group 1 PAH (210 pg/ml [interquartile range, 190–246 pg/ml] vs. 217 pg/ml [155–297 pg/ml]; P > 0.05), group 2 PH (232 pg/ml [174–264 pg/ml]; P > 0.05 vs. control subjects), or group 3 PH (220 pg/ml [151–272 pg/ml]; P > 0.05 vs. control subjects). However, among the etiologies of group 1 PAH, plasma levels of circulating BMP9 were markedly diminished in patients with PoPH compared with control subjects (46 pg/ml [21–71 pg/ml]; P < 0.0001 vs. control subjects) (Figure 2B), whereas no difference was observed with other etiologies of PAH, including IPAH, APAH-CTD, or APAH-STIM. In the derivation cohort, BMP9 levels distinguished PoPH versus non-PoPH (control subjects, group 1 PAH, and group 2 and 3 PH), with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve–area under the curve (AUC) of 0.999 ± 0.002 (P < 0.001). At a cutoff of less than 132 pg/ml, BMP9 levels identified PoPH with 100% sensitivity, 96% specificity, 65% positive predictive value, and 100% negative predictive value. Similarly, in the validation cohort (Figure 2C), BMP9 levels did not differ between control subjects and group 1 PAH, but were markedly decreased in patients with PoPH (81 [48–131 pg/ml] vs. 184 pg/ml [126–227 pg/ml]; P = 0.0028) and not IPAH or APAH-CTD (Figure 2D). In the validation cohort, BMP9 levels distinguished PoPH versus non-PoPH (control subjects and group 1 PAH) with a ROC-AUC of 0.827 ± 0.054 (P < 0.001). At a cutoff of less than 132 pg/ml, BMP9 levels identified PoPH with 76% sensitivity, 67% specificity, 43% positive predictive value, and 90% negative predictive value. To address relatively small numbers of patients with PoPH in each cohort, the derivation and validation cohorts were pooled and analyzed, revealing an aggregate ROC-AUC of 0.956 ± 0.015 (P < 0.0001), with 86% sensitivity, 89% specificity, 51% positive predictive value, and 98% negative predictive value.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Patients with PH and Healthy Control Subjects

| Derivation Cohort |

Validation Cohort |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO Group 1 PAH | PoPH | Control Subjects | WHO Group 1 PAH | PoPH | Control Subjects | WHO Group 2 PH | WHO Group 3 PH | |

| Total sample size, n | 90 | 11 | 49 | 63 | 17 | 11 | 20 | 21 |

| Sex, female subjects, n (%) | 72 (80.0)* | 6 (54.5)† | 27 (55.1) | 38 (60.3)† | 7 (41.2)† | 8 (72.7) | 14 (70.0)† | 10 (47.6)† |

| BMI, mean ± SEM | 30.2 ± 0.87‡ | 38.7 ± 2.8§ | 27.1 ± 0.89 | 28.9 ± 0.84‡ | 29.3 ± 1.4‡ | N/A | 35.8 ± 2.6|| | 31.1 ± 1.9‡ |

| Age, yr, mean ± SEM | 49.8 ± 1.5‡ | 53.9 ± 4.2‡ | 50.1 ± 1.7 | 56.3 ± 1.6‡ | 51.7 ± 2.7‡ | 49.3 ± 5.1 | 67.0 ± 2.8§ | 63.4 ± 2.9§ |

| PAH etiology, n (%) | ||||||||

| IPAH | 41 (45.6) | — | — | 27 (42.9) | — | — | — | — |

| HPAH | 2 (2.2) | — | — | 1 (1.6) | — | — | — | — |

| APAH-CTD | 20 (22.2) | — | — | 14 (22.2) | — | — | — | — |

| APAH-STIM | 9 (10.0) | — | — | 1 (1.6) | — | — | — | — |

| APAH-CHD | 3 (3.3) | — | — | 3 (4.7) | — | — | — | — |

| APAH-HIV | 2 (2.2) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| PVOD | 2 (2.2) | — | — | 17 (27.0) | — | — | — | — |

| PoPH | 11 (12.2) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Definition of abbreviations: APAH = associated PAH; BMI = body mass index; CHD = congenital heart disease; CTD = connective tissue disease; HPAH = heritable PAH; IPAH = idiopathic PAH; N/A = not available; NS = not significant (P > 0.05); PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PoPH = portopulmonary hypertension; PVOD = pulmonary venoocclusive disease; STIM = toxin or stimulant drug exposure; WHO = World Health Organization.

P = 0.01 versus cohort matched control subjects, Fisher exact test.

NS versus cohort matched control subjects, Fisher exact test.

NS versus cohort matched control subjects, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett test for multiple comparisons.

P ≤ 0.001 versus cohort matched control subjects, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett test for multiple comparisons.

P = 0.01 versus cohort matched control subjects, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett test for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of all Patients with PH

| WHO Group 1 PAH |

WHO Group 2 PH | WHO Group 3 PH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derivation Cohort | Validation Cohort | |||

| NYHA functional class, n (%)* | ||||

| Class I | 7 (9.9) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| Class II | 35 (49.3) | 26 (44.1) | 9 (60) | 6 (30) |

| Class III | 28 (39.4) | 26 (44.1) | 5 (33.3) | 11 (55) |

| Class IV | 1 (1.4) | 4 (6.8) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| 6MWD, m, mean ± SEM (n)† | 440 ± 21 (35) | 379 ± 22 (50) | 395 ± 14 (3) | 324 ± 43 (9) |

| RHC measurements, mean ± SEM (n) | ||||

| RAP, mm Hg | 9 ± 1 (32) | 9 ± 1 (62) | 13 ± 2 (17) | 8 ± 1 (21) |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 49 ± 2 (42) | 48 ± 1 (62) | 43 ± 2 (19) | 33 ± 2 (21) |

| PCWP, mm Hg | 10 ± 1 (33) | 10 ± 0.4 (62) | 25 ± 1 (19) | 12 ± 1 (21) |

| CO, L/min | 5.0 ± 0.3 (40) | 4.5 ± 0.1 (62) | 5.7 ± 0.4 (18) | 5.4 ± 0.3 (21) |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 2.6 ± 0.1 (40) | 2.4 ± 0.1 (61) | 2.7 ± 0.2 (18) | 2.8 ± 0.2 (21) |

| PVR, Wood units | 8.8 ± 0.7 (41) | 9.6 ± 0.6 (62) | 3.6 ± 0.5 (18) | 4.4 ± 0.6 (21) |

| TTE RVSP, mm Hg, mean ± SEM (n)† | 72 ± 4 (47) | 70 ± 3 (46) | 68 ± 4 (16) | 61 ± 5 (13) |

| PAH therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Prostacyclin analogue | 24 (47.1) | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Endothelin antagonist | 21 (41.2) | N/A | 2 (14.3) | 2 (15.4) |

| PDE-5 inhibitor | 38 (74.5) | N/A | 5 (35.7) | 4 (30.8) |

Definition of abbreviations: 6MWD = 6-minute-walk distance; CI = cardiac index; CO = cardiac output; mPAP = mean pulmonary artery pressure; N/A = not available; NS = not significant (P > 0.05); NYHA = New York Heart Association; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PDE = phosphodiesterase; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP = right atrial pressure; RHC = right heart catheterization; RVSP = right ventricular systolic pressure; TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram; WHO = World Health Organization.

NS differences in distribution of each group versus derivation cohort, chi-square test.

NS differences versus derivation cohort, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett test for multiple comparisons.

Figure 2.

Circulating BMP9 (bone morphogenetic protein 9) is profoundly decreased in portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH) and is a sensitive and specific predictor of PoPH. (A) Circulating BMP9 was measured in a derivation cohort comprised of 49 healthy control subjects, 90 World Health Organization group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients, 20 group 2 pulmonary hypertension patients, and 21 group 3 pulmonary hypertension patients. There are no significant differences in the abundance of BMP9 among group 1, 2, or 3 patients versus healthy control subjects (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison). (B) Among patients with group 1 PAH in the derivation cohort, circulating BMP9 was markedly diminished in patients with PoPH (n = 11); a difference is not observed in other etiologies of group 1 PAH, including idiopathic PAH (IPAH; n = 41), PAH associated with connective tissue disease (APAH-CTD; n = 20), or PAH associated with stimulant use (APAH-STIM; n = 9) (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison). (C and D) There was a nonsignificant trend toward decreased BMP9 levels in patients with group 1 PAH from a distinct derivation cohort (58 patients with PAH) (C), with a similarly marked decrease in circulating BMP9 among 17 patients with PoPH (Mann-Whitney test) (D) but not among 27 patients with IPAH and 14 patients with APAH-CTD (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison). Data are expressed as median and interquartile range, and P values are indicated. NS = not significant (P > 0.05).

Patients with PoPH Exhibit Dysregulated BMP9-Endoglin Signaling

Endoglin functions as a BMP9 coreceptor on the cell membrane, whereas sEng functions as a BMP9 ligand trap in the circulation (12). sEng dose-dependently inhibited BMP9 signaling activity in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells with an IC50 of approximately 250 ng/ml (see Figure E2A). We confirmed as previously reported that serum levels of sEng are increased in the patients with group 1 PAH (9) as compared with control subjects (5.6 ng/ml [interquartile range, 4.5–7.0 ng/ml] vs. 4.0 ng/ml [3.4–4.9 ng/ml]; P < 0.0001) (see Figure E2B). In contrast to BMP9, sEng was increased in IPAH (5.4 ng/ml [4.2–6.4]; n = 35; P = 0.0142 vs. control subjects), and yet more elevated in PoPH versus other etiologies (6.5 ng/ml [5.9–9.1 ng/ml], P < 0.0001 vs. control, P = 0.01 vs. IPAH, P = 0.036 vs. APAH-CTD, and P = 0.012 vs. APAH-STIM) (see Figure E2C). Levels of sEng correlated minimally with levels of BMP9 (r = −0.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.24 to 0.026; P = 0.11). Despite the greater levels of sEng seen in PoPH than other group I PAH, the ability of the BMP9/sEng ratio to distinguish PoPH from other group 1 PAH was not significantly different than BMP9 alone (AUC, 0.90 ± 0.03; P < 0.0001) (see Figures E2D and E2E).

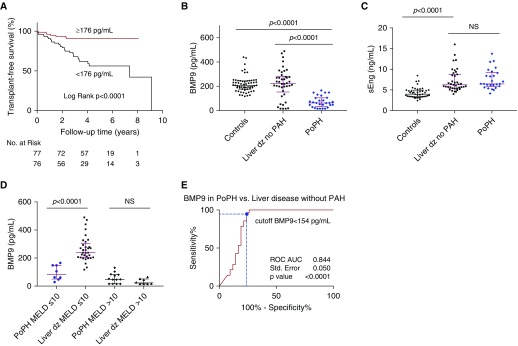

BMP9 Levels Predict Transplant-Free Survival in Patients with Group 1 PAH

The 5-year transplant-free survival for patients with group 1 PAH, defined as survival without lung transplantation, was 73.5%. Among the hemodynamic and clinical parameters (Table 2), univariate predictors of transplant-free survival included age, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, 6-minute-walk distance, BNP (brain natriuretic peptide), and right atrial pressure measured by right heart catheterization (Table 3). Importantly, BMP9 predicted transplant-free survival among patients with group 1 PAH with a Cox hazard ratio (HR) of 0.66 for every 50-pg/ml increase (95% CI, 0.54–0.81; P < 0.001) (Table 3), and was an independent predictor of transplant-free survival among patients with PAH even after adjusting for age, BNP levels, NYHA functional class, 6-minute-walk distance, and right atrial pressure (Cox HR, 0.74 for every 50-pg/ml increase; 95% CI, 0.56–0.97; P = 0.03). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis within this cohort of patients with PAH was performed with BMP9 levels dichotomized around the median value of 176 pg/ml (Figure 3A), revealing a 76% reduced hazard for death or transplant for patients with BMP9 greater than or equal to 176 pg/ml (Cox HR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.12–0.47; P < 0.0001) compared with those with levels less than 176 pg/ml. The association of BMP9 with survival was not caused strictly by patients with PoPH, because this association was still significant among PAH excluding PoPH (Cox HR, 0.77 for every 50-pg/ml increase; 95% CI, 0.63–0.95; P = 0.013), and among PAH adjusting for PoPH (Cox HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62–0.93; P = 0.007). In contrast to BMP9, sEng did not predict transplant-free survival (Cox HR, 1.08 for every 1-ng/ml increase; 95% CI, 0.95–1.24; P = 0.242) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate Predictors of Transplant-Free Survival in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

| Variable | Cox Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (for every 10-yr increase) | 1.42 (1.10–1.82) | 0.007 |

| NYHA (for each class increase) | 2.33 (1.41–3.84) | 0.001 |

| 6-min-walk distance (for every 50-m increase) | 0.82 (0.71–0.94) | 0.004 |

| Right atrial pressure (for every 5-mm Hg increase) | 1.50 (1.17–1.91) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac index (for every 1-L/min/m2 increase) | 0.66 (0.39–1.11) | 0.116 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (for every 1-WU increase) | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) | 0.057 |

| BNP (for every 100-pg/ml increase) | 1.20 (1.11–1.30) | 0.001 |

| BMP9 (for every 50-pg/ml increase) | 0.66 (0.54–0.81) | <0.001 |

| sEng (for every 1-nl/ml increase) | 1.08 (0.95–1.24) | 0.242 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMP = bone morphogenetic protein; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA = New York Heart Association; sEng = soluble endoglin; WU = Wood units.

Figure 3.

BMP9 (bone morphogenetic protein 9) predicts transplant-free survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and predicts the presence of portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH) in liver disease. (A) Cumulative survival without lung transplant in patients with group 1 PAH is depicted by Kaplan-Meier survival curves dichotomized about the median value for circulating BMP9 of 176 pg/ml. Patients with PAH with a BMP9 level ≥176 pg/ml (red line) exhibit a 76% reduced hazard for death or lung transplant (Cox hazard ratio, 0.240; 95% confidence interval, 0.123–0.468; P < 0.0001) compared with those with BMP9 <176 pg/ml (black line). Transplant-free survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. (B) Circulating BMP9 was measured in 60 healthy control individuals, 42 patients with liver disease without known pulmonary vascular disease, and 28 patients with PoPH. BMP9 levels were substantially lower in PoPH compared with patients with liver disease without known PAH (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison). (C) Circulating soluble form of endoglin (sEng) was measured in plasma collected from 26 patients with PoPH and 39 patients with liver disease without a diagnosis of PAH. In contrast to BMP9, no significant difference was found in circulating sEng between PoPH and patients with liver disease without PAH. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range, and P values are indicated. NS = not significant (P > 0.05) (Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparison). (D) Among patients with less severe liver dysfunction defined by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores ≤10, BMP9 was significantly lower in PoPH versus liver disease without PAH. There was no significant difference in BMP9 levels among patients with severe liver disease defined by MELD score >10. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range, and P values are indicated. NS = not significant (P > 0.05) (separate Mann-Whitney tests for MELD ≤10 and >10). (E) Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis reveals that diminished circulating BMP9 is a highly sensitive and specific predictor of PoPH among all patients with known liver disease, using a cutoff BMP9 level of <154 pg/mL (dashed blue lines); black line = no discrimination. AUC = area under the curve; dz = disease.

Among patients with group 1 PAH, BNP was elevated primarily in highly symptomatic disease (NYHA functional class III-IV) and correlated with increasing NYHA functional class (see Figure E3A). As previously reported (9), sEng was elevated even in mildly symptomatic disease (NYHA functional class I-II) compared with healthy control subjects, but in contrast to BNP, neither sEng nor BMP9 correlated significantly with NYHA functional class (see Figures E3B and E3C).

Diminished BMP9 Levels Sensitively Predict PoPH in Patients with Liver Disease

Circulating BMP9 was measured in 42 patients with liver disease of varying etiology and severity, without evidence of PAH based on negative screening echocardiograms and lack of clinical symptoms. Baseline demographic and clinical data for this patient population and 28 patients with PoPH are presented in Table 4. BMP9 was significantly lower in patients with PoPH compared with patients with liver disease without evidence of PAH (63 pg/ml [interquartile range, 37–104 pg/ml] vs. 223 pg/ml [153–282 pg/ml]; P < 0.0001) (Figure 3B). In contrast to BMP9 there was no difference in sEng levels between PoPH and liver disease without PAH (6.5 ng/ml [5.9–9.1 ng/ml] vs. 6.2 ng/ml [5.4–8.8 ng/ml]; P > 0.05) (Figure 3C). In this population, BMP9 correlated positively with albumin (r = 0.69; P < 0.0001) and platelet count (r = 0.53; P < 0.0001), and negatively with total bilirubin (r = −0.71; P < 0.0001) and international normalized ratio (r = −0.72; P < 0.0001), but demonstrated no significant correlation with creatinine (P = 0.07) (see Figures E4A–E4F). In agreement, there was a strong negative correlation between BMP9 and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (r = −0.84; P < 0.0001) (see Figure E4E), a composite measure of liver disease severity and prognosis. We tested the correlation of BMP9 levels with the degree of histologic liver fibrosis according to Ishak fibrosis stage, scored in liver biopsy samples available from 34 patients with liver disease without known PAH. There was a marginal negative correlation between BMP9 levels and the Ishak fibrosis score (r = −0.31; P = 0.07) (see Figure E5A).

Table 4.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Liver Disease without PAH versus Patients with PoPH

| Liver Disease and No PAH | PoPH | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample Size, n | 42 | 28 |

| Etiology of liver disease, n | ||

| HCV | 33 | 9 |

| Alcohol | 3 | 4 |

| HCV and alcohol | 2 | 2 |

| HPS and HCV | 1 | 0 |

| HPS and alcoholic hepatitis | 1 | 0 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 2 | 0 |

| NAFLD | — | 1 |

| Unknown etiology | — | 7 |

| Other* | — | 5 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SEM | 53.1 ± 1.9† | 52.6 ± 2.3† |

| Sex, female subjects, n (%) | 14 (33.3)‡ | 14 (50.0)‡ |

| MELD score, median (IQR) | 7.5 (6.4–9.9)§ | 12.5 (10.2–15.0)§ |

Definition of abbreviations: HCV = hepatitis C virus; HPS = hepatopulmonary syndrome; IQR = interquartile range; MELD = Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NAFLD = nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NS = not significant (P > 0.05); PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; PoPH = portopulmonary hypertension.

Other includes: biliary atresia (n = 1), biliary cirrhosis (n = 1), hepatitis B (n = 1), Budd-Chiari syndrome (n = 1), Abernathy malformation (n = 1).

NS, Student’s t test.

NS, Fisher exact test.

P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney test.

Because MELD scores were higher among PoPH than with liver disease without PAH (Table 4), two approaches were used to test if BMP9 could discriminate PoPH versus liver disease independently of disease severity. First, stratification of individuals into groups with mild (MELD ≤10) or moderate-severe disease (MELD >10) revealed significantly lower BMP9 levels in PoPH, but only among the mild disease group (84 pg/ml [54–148 pg/ml] vs. 239 pg/ml [205–293 pg/ml]; P < 0.0001) (Figure 3D). Second, a multivariable logistic regression was performed comparing BMP9 with liver disease indices albumin, international normalized ratio, creatinine, platelet count, and MELD score as predictors of PoPH. When compared with each of these liver function indices individually or as a group, BMP9 was the only significant predictor of PoPH, with an odds ratio of 0.325 (per 50-pg/ml increase in BMP9 95% CI, 0.157–0.673; P = 0.002). Consistent with these results, ROC analysis of BMP9 as a discriminator of PoPH among all patients with liver disease yielded an AUC of 0.844 ± 0.050 (P < 0.001), with BMP9 levels of less than 154 pg/ml exhibiting sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 76% for PoPH (Figure 3E). Similarly, among liver disease with MELD less than or equal to 10, BMP9 levels less than 154 pg/ml were 88% sensitive and 94% specific for PoPH (AUC, 0.974 ± 0.022; P < 0.0001) (see Figure E5B).

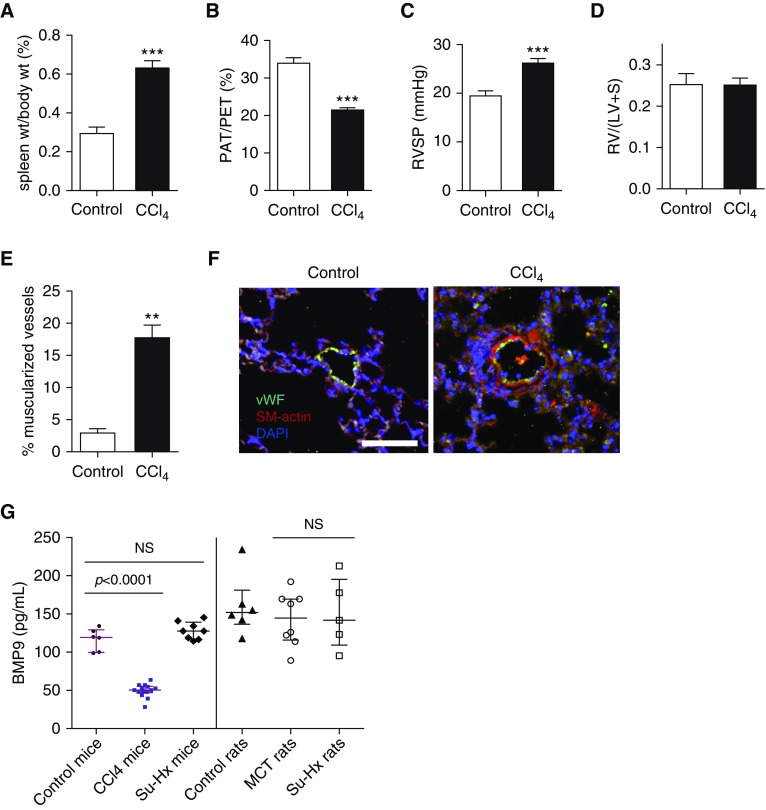

CCl4-induced Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension in Mice Is Accompanied by Mild PH and Diminished Circulating BMP9

To test if the clinical association of PoPH and BMP9 deficiency could be replicated in an animal model, mice were induced to develop cirrhosis and portal hypertension after receiving CCl4 for 16 or 20 weeks. As previously described (18), splenomegaly, as evidence of portal hypertension, was documented by elevated spleen to body weight ratios in CCl4-treated mice compared with control animals (0.63 ± 0.04 vs. 0.30 ± 0.03; mean ± SEM; P < 0.0001) (Figure 4A). The impact of cirrhosis on the pulmonary circulation was assessed by echocardiography and confirmed by right heart catheterization. At 16 weeks, CCl4-treated mice exhibited reduced pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAT) (11.9 ± 0.3 ms vs. 19.3 ± 0.8 ms in control animals; P < 0.0001) and PAT to pulmonary ejection time (PET) ratios (PAT/PET) (21.5 ± 0.6 vs. 34.2 ± 1.2 in control animals; P < 0.0001) (Figure 4B), similar to previous (18). CCl4-treated mice demonstrated mildly elevated RV pressures compared with control animals (26.2 ± 1.0 mm Hg vs. 19.6 ± 0.9 mm Hg; P = 0.0002) (Figure 4C). Consistent with mild PH, there was no difference in Fulton index between CCl4-treated and control mice (Figure 4D); however, CCl4-treated mice exhibited significantly increased muscularization of small pulmonary arterioles (<50 μm) (Figures 4E and 4F). After 16 weeks of CCl4, circulating levels of BMP9 were decreased in CCl4-treated mice versus control animals (88.2 ± 9.6 pg/ml vs. 162.9 ± 12.3 pg/ml; P = 0.0003), and yet lower after 20 weeks of CCl4 (49.5 ± 2.3 pg/ml vs. 116.6 ± 5.88; P < 0.0001 vs. control animals) (Figure 4G), comparable with the relative decreases in BMP9 levels in patients with PoPH versus healthy control subjects. Supporting the specificity of decreased BMP9 in PH associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, BMP9 levels were preserved in all other rodent models of PH examined, including mice and rats with severe PH induced by SU5416 and hypoxia, and rats with severe PH induced by monocrotaline (Figure 4G). Furthermore, BMP9 levels correlated inversely with RV systolic pressure measured by catheterization (r = −0.83; P = 0.0005), and correlated with PAT (r = 0.60; P = 0.02, data not shown) and PAT/PET ratio (r = 0.66; P = 0.01) (see Figures E6A and E6B), suggesting that the severity of PH may be related to the degree of BMP9 deficiency.

Figure 4.

Mice with portal hypertension exhibit mild pulmonary hypertension and reduced levels of circulating BMP9 (bone morphogenetic protein 9). Male C57BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks (n = 9) were treated with phenobarbital (0.35 g/L) via drinking water and CCl4 in olive oil (1:5; 0.4 ml/kg body weight, i.p. 3 times/wk) or vehicle (n = 10) for 16 weeks, at the end of which they underwent right heart catheterization. Two groups were compared using unpaired Student’s t test. (A) CCl4-treated mice develop splenomegaly because of portal hypertension based on elevated spleen to body weight ratio versus vehicle-treated animals. (B) Cardiac ultrasound demonstrates presence of pulmonary hypertension in CCl4-treated mice based on a reduced ratio of pulmonary artery acceleration time to pulmonary ejection time. (C) CCl4-treated mice develop mild pulmonary hypertension based on a mild but significant increase in right ventricular systolic pressure compared with control animals. (D) There was no difference in right ventricular hypertrophy between control and CCl4-treated mice. (E and F) Quantification and representative photomicrographs of immunofluorescence of lung sections for von Willebrand factor and smooth muscle α-actin revealed increased muscularization of small (≤50 μm) arterioles in CCl4-treated mice (bar = 100 μm). (G) Levels of circulating BMP9 were significantly lower in mice treated with CCl4 for 20 weeks (n = 14) than control mice (n = 6) (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparison), comparable with decreased levels observed in patients with portopulmonary hypertension. Compared with control mice, levels of BMP9 were unchanged in mice treated with SUGEN/hypoxia (Su-Hx; n = 8). Similarly, compared with control rats, BMP9 levels were unchanged in rats treated with monocrotaline (n = 8) or Su-Hx (n = 5) (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparison). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, with P values given in the figure or by asterisks as follows: **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. LV = left ventricle; MCT = monocrotaline; NS = not significant (P > 0.05); PAT = pulmonary artery acceleration time; PET = pulmonary ejection time; RV = right ventricle; RVSP = right ventricular systolic pressure; S = septum; SM-actin = smooth muscle α-actin; vWF = von Willebrand factor; wt = weight.

BMP9 Ligand Trap ALK1-Fc Potentiates Hypoxia-induced PH

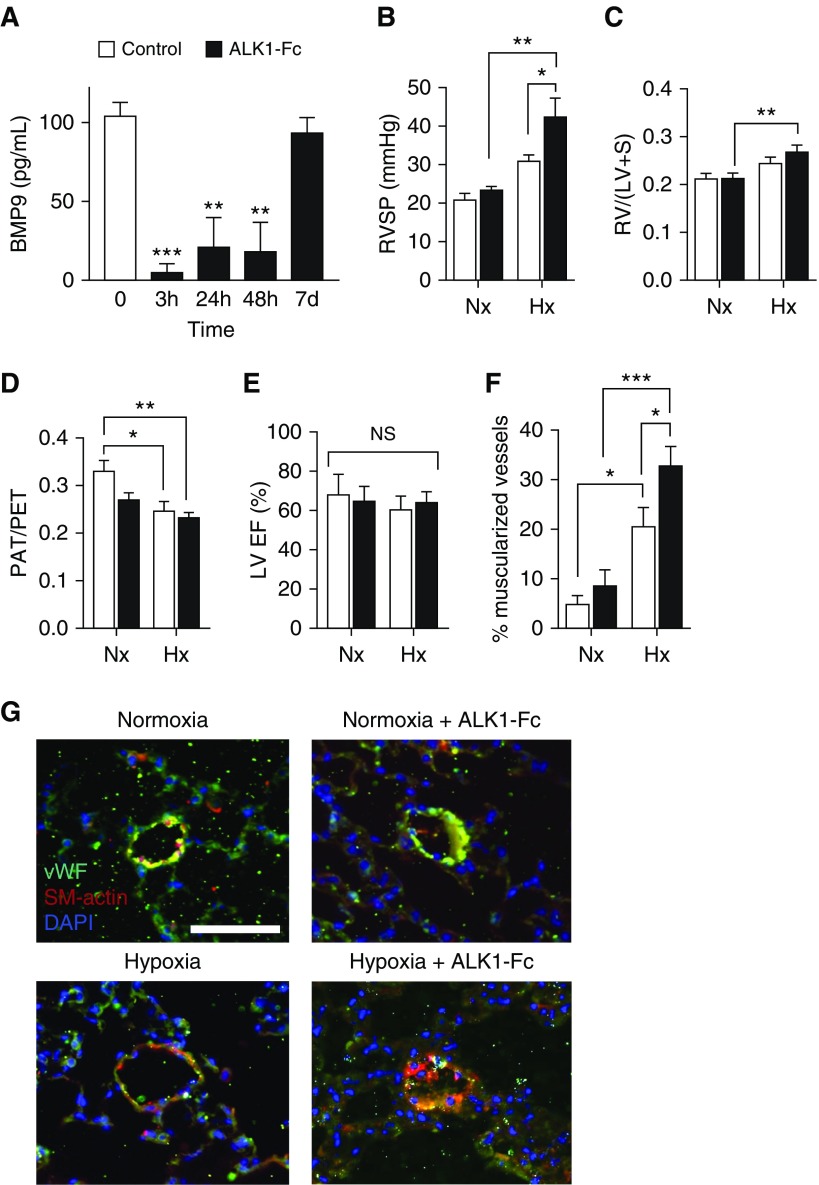

To determine whether neutralizing circulating BMP9 could trigger or potentiate PH, we administered the BMP9 ligand trap, ALK1-Fc, to mice under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Exogenous ALK1-Fc was previously shown to antagonize angiogenic activity and reduce tumor burden in a tumor xenograft model (19). A single injection of ALK1-Fc (5 mg/kg i.p.) reduced plasma BMP9 levels at 3, 24, and 48 hours after injection (n = 4; P < 0.01) (Figure 5A), and reduced expression of BMP target genes Id1 and Id3 in whole lung tissues of ALK1-Fc versus vehicle-treated mice at 48 hours (n = 4; P < 0.05) (see Figure E7). Administration of ALK1-Fc (5 mg/kg i.p. weekly for 3 wk) to adult mice under normoxic conditions did not lead to measurable PH or RV hypertrophy, but caused a nonsignificant decrease in PAT/PET ratio compared with normoxic control animals (P = 0.06) (Figures 5B–5D) without inducing a change in cardiac function measured by left ventricular ejection fraction (Figure 5E). Exposure to hypoxia (FiO2, 0.10) alone caused a typical moderate degree of PH, which was markedly worsened by ALK1-Fc (31.3 ± 1.3mm Hg vs. 42.8 ± 4.6 mm Hg; P = 0.04). ALK1-Fc did not exacerbate the RV hypertrophy associated with hypoxia alone (Figure 5C), but markedly worsened the degree of pulmonary vascular remodeling based on increased muscularization of small arterioles (<50 μm diameter) (Figures 5F and 5G; see Figure E8). In contrast, administration of sEng-Fc or ALK3-Fc neither induced or exacerbated PH in normoxic or hypoxia-exposed mice (see Figure E9). Taken together, these data suggest that a high-affinity BMP9 ligand trap, such as ALK1-Fc, may exacerbate PH induced by exposure to hypoxia, whereas a relatively lower-affinity trap, such as sEng-Fc, or a BMP2/4 ligand trap, such as ALK3-Fc, do not exhibit this effect.

Figure 5.

Administering BMP9 (bone morphogenetic protein 9) ligand trap ALK1-Fc induces severe pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in mice treated with hypoxia. (A) Administration of ALK1-Fc (5 mg/kg i.p. single injection) to adult C57BL/6 mice reduced plasma BMP9 levels at 3, 24, and 48 hours (P < 0.01; repeated measures one-way ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparison). (B–G) Adult C57BL/6 mice received either vehicle or ALK1-Fc (5 mg/kg i.p. twice in 3 wk) under normoxic or hypoxic (FiO2, 0.10) conditions for a total of 3 weeks. (B) Exposure to hypoxia alone (n = 7) resulted in moderately increased right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) versus control subjects (n = 5), whereas mice receiving ALK1-Fc while exposed to hypoxia (n = 8) exhibited markedly increased RVSP as compared with hypoxia, normoxia, or ALK1-Fc mice treated under normoxia groups. (C) Exposure to hypoxia resulted in significantly increased Fulton index [RV/(LV + S)], which was not significantly increased by the addition of ALK1-Fc. (D) Treatment with ALK1-Fc under normoxic or hypoxic conditions, or exposure to hypoxia alone all decreased pulmonary artery acceleration time/pulmonary ejection time. (E) ALK1-Fc treatment does not alter cardiac function measured by left ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening measured by echocardiography. (F) Exposure to hypoxia increased the proportion of muscularized small arterioles (≤50 μm) based on smooth muscle α-actin (SM-actin) expression, which was further increased in mice receiving ALK1-Fc under hypoxia, shown (G) by costaining for SM-actin and von Willebrand factor (bar = 50 μm). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, groups compared using two-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons tests. Hx = hypoxic; LV = left ventricle; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NS = not significant (P > 0.05); Nx = normoxic; PAT = pulmonary artery acceleration time; PET = pulmonary ejection time; RV = right ventricle; S = septum; vWF = von Willebrand factor.

Discussion

The ligand BMP9, its cognate receptors BMPR2 and ALK1, and coreceptor endoglin represent a discrete signaling axis that directly targets the vascular endothelium (13), with potent antiapoptotic and homeostatic functions in the pulmonary vasculature (11, 15, 20). Loss-of-function mutations in each of these signaling molecules have been previously associated with HPAH and PH overlap syndromes including hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and juvenile polyposis syndromes (21, 22). We investigated circulating levels of BMP9 and its secreted antagonist sEng as candidate biomarkers in PAH. Levels of circulating BMP9 were sufficiently high in healthy individuals (∼200 pg/ml) in comparison with its measured EC50 of 16 pg/ml in endothelial cells to elicit signaling, and accounted for 80–100% of the endothelial BMP signaling activity in human serum (Figure 1; see Figure E1). We found that BMP9 is a sensitive biomarker that segregates PoPH from other types of PAH, group 2 and 3 PH, and may represent a risk for PoPH that is not represented by standard indices of liver disease. Consistent with human disease, circulating BMP9 was depleted in rodents with PH caused by cirrhosis and portal hypertension, but remained intact in other rodent models of PH. Consistent with the idea that diminished BMP9 might be a risk factor or driver for PH, the potent BMP9 ligand trap ALK1-Fc did not trigger PH, but severely exacerbated PH and pulmonary vascular remodeling caused by hypoxia. Although sEng was higher in PoPH than IPAH or APAH-CTD, sEng did not discriminate between patients with liver disease without PAH versus PoPH (Figures 3B and 3C). The modest ligand-trapping effect of sEng (see Figure E2A) could potentially compound the effects of diminished circulating BMP9 and contribute to the pathogenesis of PoPH, yet an effect of sEng-Fc was not observed in hypoxic mice (see Figure E9). The role of BMP9 highlighted by the human genetics of PAH, its impact in experimental PH, and its characteristics as a potential biomarker of PoPH support the concept that acquired deficiency of BMP9 may link the pathogenesis of PoPH to heritable, syndromic forms of PAH.

The localization of BMP9 expression to hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells, and/or biliary epithelial cells is consistent with its diminished expression in PoPH (20, 23). Recently it was reported that in addition to BMP9 homodimers, BMP9/BMP10 heterodimers seem to exist in the circulation based on immunodetection, immune depletion, and genetic depletion methods, and may arise from coexpression of these ligands in hepatic stellate cells (24). Both BMP9 homodimer and BMP9/BMP10 heterodimer would be detected by the assays of this study, and would be inhibited by ALK1-Fc or neutralizing antibody, making observations of this study attributed to BMP9 homodimer applicable to BMP9/BMP10 heterodimer. Direct biochemical assessments of the abundance and function of these species would be needed to discern their relative contributions to the pathophysiology of PoPH or PAH.

We acknowledge limitations of the current study because of the size of the cohorts; the inclusion of incident and prevalent cases of PAH; and differences in the source populations and care settings for obtaining PAH, PoPH, liver disease, and control samples. We acknowledge the limitations of enriching this study with enrollment from two liver transplant screening programs with a higher prevalence of PoPH than the estimated 2–5% among patients with portal hypertension or 8.5% among those undergoing liver transplant (25). We note also that a sizable fraction of patients with liver disease without known PAH had BMP9 levels less than the proposed cutoff of 154 pg/ml (Figure 3B), but whether or not these levels may predict risk for PoPH is not known. Prospective longitudinal studies evaluating the performance of BMP9 as a predictor of PoPH among at-risk patients with liver disease with a typical prevalence of disease is required to validate these concepts.

There remains an unmet need for biomarkers that can detect pulmonary vascular disease before the onset of severe symptoms and end-organ damage. Because PoPH carries a worse prognosis than other etiologies of PAH (26), with a 5-year mortality of 55% without liver transplant (25), earlier identification could facilitate medical or surgical treatment when it may still be effective or feasible. In a stratified analysis of patients with mild liver disease, BMP9 levels segregated patients with PoPH from those without PAH. In a multivariable logistic regression, BMP9 outperformed other liver disease indices in predicting PoPH among patients with liver disease, suggesting that BMP9 is more than a marker of liver disease itself. Accordingly, BMP9 did not correlate with Ishak liver fibrosis scores. BMP9 was predictive of transplant-free survival in patients with group 1 PAH, including or excluding patients with PoPH, yet was not correlated with NYHA functional class, right atrial pressure, or BNP (see Figure E3C, and data not shown) among patients with PAH, suggesting that BMP9 predicts survival independent of RV function. Among the animal models of PH, BMP9 was diminished only in rodents with severe cirrhosis, but preserved in SU5416/hypoxia-treated mice and rats, and monocrotaline-treated rats despite the known hepatotoxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (27). Taken together, these results suggest that BMP9 levels are linked to PoPH via portal hypertension rather than liver injury or synthetic dysfunction alone.

The concept that BMP9 deficiency may contribute to PoPH is further supported by our previous work in which administration of exogenous BMP9 ameliorated PH caused by toxin exposure or loss of BMPR2 function (11). Although potential hurdles may exist in the therapeutic use of BMP9, including the theoretical risk of heterotopic ossification (28), other strategies to modulate BMP9 signaling could potentially be applied to PoPH or PAH. Conversely, neutralizing BMP9 with ALK1-Fc does not cause PH by itself, but potentiates hypoxia-induced PH in mice, suggesting that deficient BMP9 signaling may synergize with other pulmonary vascular insults present in end-stage liver disease, akin to unknown “second hits” required for the penetrance of HPAH-causing mutations. We speculate that the chronic high-flow, high-output state associated with portal hypertension and cirrhosis may interact with diminished BMP9 homeostatic activity to precipitate PoPH. We note beyond the potential endocrine impact of hepatic BMP9 on the pulmonary circulation that BMP9 has important autocrine and paracrine effects on hepatocyte growth and function, liver fibrosis, and remodeling (23, 29, 30), functions that may impact the evolution of underlying liver disease and therapeutic efforts to modulate BMP9.

In summary, we have identified acquired loss of BMP9 as a potential risk factor for PoPH, possibly because of a loss of tonic protective signaling, and have developed a novel rodent model of severe PH and remodeling caused by acquired loss of BMP9 function. These findings highlight a previously unappreciated mechanistic link between nongenetic and genetic forms of PAH, and may provide clues as to the identity of other penetrance factors or environmental “hits” that synergize with diminished BMP signaling to cause PAH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. Kenneth Bloch, Donald Bloch, and Peter ten Dijke for their critical feedback on this work.

Footnotes

Supported by funding from the NIH (HL079943, HL131910, HL132742, and AR057374, P.B.Y.; T32HL007604, I.N.; DK108370 and DK098079, R.T.C.), the John S. LaDue Fellowship at Harvard Medical School (I.N.), a Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Program award in pulmonary arterial hypertension (L.-M.Y.), a Pulmonary Hypertension Association Clinician-Scientist Award (P.B.Y.), a Leducq Foundation Transatlantic Network of Excellence Award (P.B.Y. and N.W.M.), the British Heart Foundation (N.W.M. and P.D.U.), a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Physician-Scientist Award (P.B.Y.), a research grant from the Pfizer Centers for Therapeutic Innovation (P.B.Y.), and with support from Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development (K.E.T., K.R.C., S.P.B., and C.H.).

Author Contributions: I.N., L.-M.Y., P.Y., P.D.U., N.W.M., R.T.C., R.W.C., K.E.R., and P.B.Y. conceived of and designed the study. I.N., L.-M.Y., P.Y., S.D.P.-F., T.D., G.A.B., K.E.T., L.T., M.E.M., X.H., K.R.C., A.L., and P.B.Y. performed experiments. I.N., S.D.P.-F., A.J.F., C.S.C.L., R.T.Z., C.G.E., R.T.C., R.W.C., K.E.R., and P.B.Y. enrolled patients and reviewed clinical data. I.N., L.-M.Y., P.Y., R.M., G.A.B., P.D.U., N.W.M., R.T.C., K.E.R., and P.B.Y. analyzed data. I.N., L.-M.Y., P.Y., R.M., G.A.B., P.D.U., M.J.G., R.T.Z., C.G.E., A.L., W.Z., S.P.B., C.H., N.W.M., K.E.R., and P.B.Y. drafted and revised the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1236OC on October 12, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, Frantz R, Khanna D, Kurzyna M, et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(Suppl 25):D42–D50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(Suppl. 25):D34–D41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA, III, Loyd JE, et al. International PPH Consortium. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng Z, Morse JH, Slager SL, Cuervo N, Moore KJ, Venetos G, et al. Familial primary pulmonary hypertension (gene PPH1) is caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:737–744. doi: 10.1086/303059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soubrier F, Chung WK, Machado R, Grünig E, Aldred M, Geraci M, et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(Suppl. 25):D13–D21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW, Gallione CJ, Baldwin MA, Jackson CE, et al. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg JN, Gallione CJ, Stenzel TT, Johnson DW, Allen WP, Schwartz CE, et al. The activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene: genomic structure and mutations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:60–67. doi: 10.1086/513903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Fan R, Ji R, Zou W, Penny DJ, Varghese NP, et al. Novel homozygous BMP9 nonsense mutation causes pulmonary arterial hypertension: a case report. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:17. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malhotra R, Paskin-Flerlage S, Zamanian RT, Zimmerman P, Schmidt JW, Deng DY, et al. Circulating angiogenic modulatory factors predict survival and functional class in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:369–380. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.110445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long L, Ormiston ML, Yang X, Southwood M, Gräf S, Machado RD, et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Med. 2015;21:777–785. doi: 10.1038/nm.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castonguay R, Werner ED, Matthews RG, Presman E, Mulivor AW, Solban N, et al. Soluble endoglin specifically binds bone morphogenetic proteins 9 and 10 via its orphan domain, inhibits blood vessel formation, and suppresses tumor growth. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30034–30046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David L, Mallet C, Mazerbourg S, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Identification of BMP9 and BMP10 as functional activators of the orphan activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) in endothelial cells. Blood. 2007;109:1953–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolan-Stevaux O, Zhong W, Culp S, Shaffer K, Hoover J, Wickramasinghe D, et al. Endoglin requirement for BMP9 signaling in endothelial cells reveals new mechanism of action for selective anti-endoglin antibodies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upton PD, Davies RJ, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and activin type II receptors balance BMP9 signals mediated by activin receptor-like kinase-1 in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15794–15804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David L, Mallet C, Keramidas M, Lamandé N, Gasc JM, Dupuis-Girod S, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-9 is a circulating vascular quiescence factor. Circ Res. 2008;102:914–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kienast Y, Jucknischke U, Scheiblich S, Thier M, de Wouters M, Haas A, et al. Rapid activation of bone morphogenic protein 9 by receptor-mediated displacement of pro-domains. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:3395–3410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.680009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das M, Boerma M, Goree JR, Lavoie EG, Fausther M, Gubrij IB, et al. Pathological changes in pulmonary circulation in carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced cirrhotic mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell D, Pobre EG, Mulivor AW, Grinberg AV, Castonguay R, Monnell TE, et al. ALK1-Fc inhibits multiple mediators of angiogenesis and suppresses tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:379–388. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidart M, Ricard N, Levet S, Samson M, Mallet C, David L, et al. BMP9 is produced by hepatocytes and circulates mainly in an active mature form complexed to its prodomain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0751-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wooderchak-Donahue WL, McDonald J, O’Fallon B, Upton PD, Li W, Roman BL, et al. BMP9 mutations cause a vascular-anomaly syndrome with phenotypic overlap with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald JE, Miller FJ, Hallam SE, Nelson L, Marchuk DA, Ward KJ. Clinical manifestations in a large hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) type 2 kindred. Am J Med Genet. 2000;93:320–327. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000814)93:4<320::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breitkopf-Heinlein K, Meyer C, König C, Gaitantzi H, Addante A, Thomas M, et al. BMP-9 interferes with liver regeneration and promotes liver fibrosis. Gut. 2017;66:939–954. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tillet E, Ouarné M, Desroches-Castan A, Mallet C, Subileau M, Didier R, et al. A heterodimer formed by bone morphogenetic protein 9 (BMP9) and BMP10 provides most BMP biological activity in plasma. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:10963–10974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saleemi S. Portopulmonary hypertension. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5:5–9. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.58953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krowka MJ, Miller DP, Barst RJ, Taichman D, Dweik RA, Badesch DB, et al. Portopulmonary hypertension: a report from the US-based REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2012;141:906–915. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamashita Y, Fujise N, Imai E, Masunaga H. Reduction of monocrotaline-induced hepatic injury by deleted variant of hepatocyte growth factor (dHGF) in rats. Liver. 2002;22:302–307. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leblanc E, Trensz F, Haroun S, Drouin G, Bergeron E, Penton CM, et al. BMP-9-induced muscle heterotopic ossification requires changes to the skeletal muscle microenvironment. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1166–1177. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song JJ, Celeste AJ, Kong FM, Jirtle RL, Rosen V, Thies RS. Bone morphogenetic protein-9 binds to liver cells and stimulates proliferation. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4293–4297. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bi J, Ge S. Potential roles of BMP9 in liver fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:20656–20667. doi: 10.3390/ijms151120656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.