Abstract

Background:

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is a common consequence of multiple myeloma (MM) among those commonly treated with older-generation proteasome inhibitors (PIs). In this study, we evaluated the economic burden attributable to PN among MM patients in real-world practice settings in the US.

Methods:

Adults diagnosed with MM and first treated (index event) between 1 July 2006 and 28 February 2017 were identified from MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare claim databases. Continuous enrollment for at least 12 months without treatment and PN diagnoses were required pre-index. Patients were followed for at least 3 months until inpatient death or end of data. The International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes were used to identify PN. Propensity-score matching was applied to match every patient with PN to two MM patients without a PN diagnosis (controls). Healthcare utilization and expenditures per patient per month (PPPM) in the postindex period were estimated.

Results:

Of 11,851 patients meeting the study criteria, 15.5% had PN. After matching 1387 patients with PN and 2594 controls were identified. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between cohorts; mean follow up was 23–26 months. PPPM total costs were significantly higher by $1509 for patients with PN than controls, driven by higher hospitalization (PN 77.4%, controls 67.2%; p < 0.001) and emergency department rates (PN 67.8%, controls 58.4%; p < 0.001) and more outpatient hospital-based visits PPPM (PN 13.5 ± 14.7, controls 11.5 ± 18.0; p < 0.001).

Conclusions:

PN is a prevalent MM treatment complication associated with a significant economic burden adding to the complexity and cost of MM treatment. Highly effective novel treatments such as carfilzomib may reduce the overall disease burden.

Keywords: chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, healthcare costs, line of therapy, multiple myeloma, peripheral neuropathy

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a systemic malignancy of plasma cells in bone marrow, with approximately 30,280 incident cases estimated to be diagnosed in the United States in 2017 (17,940 men and 12,790 women). MM primarily affects the elderly population since the median age at incidence is 69 years.1,2 For several decades, the standard treatment approach has been induction therapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation for transplant-eligible patients and high-dose chemotherapy for other patients. While the recent introduction of many novel therapies such as immunomodulating agents, proteasome inhibitors (PIs), monoclonal antibodies, and histone deacetylase inhibitor have shown improved response, progression-free survival3–9 and survival rates10 in clinical trials, MM remains an incurable malignancy for the majority of patients.11

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is a common complication of MM and one of the main dose-limiting iatrogenic toxicities associated with some antimyeloma treatments, including older-generation PIs such as bortezomib.12–16 The incidence of PN associated with MM treatments during the course of the disease and treatment has been estimated to range between 21% and 70% depending on the treatment and PN severity.15 MM treatment options are often limited by the likelihood of therapies causing or exacerbating neuropathies with significant negative impacts on patient quality of life.14,16 Treatment-induced PN, although usually reversible, can cause severe pain and affect the patient’s activities of daily living, as well as causing serious problems, such as loss of sensation, balance issues, muscle weakness, and organ failure.15–18

Management of PN is an ongoing challenge for healthcare providers. Actions to mitigate the incidence and effects of PN may include dosage and dosing-schedule adjustments of PIs, PI treatment discontinuation, other modalities (e.g. electrical nerve stimulation, physical therapy, acupuncture, other), and medications to address the pain (e.g. topical analgesics, antidepressants, antiepileptics, opioids).16,19 These treatment measures for managing the effects of PN also carry an economic burden for the healthcare system (e.g. increased visits to monitor or treat the PN, costs of PN treatment), as well as significant financial and lifestyle repercussions for the MM patient.

The impact of PN on healthcare utilization and costs for MM patients treated in real-world practice settings is not well understood. The purpose of this study was to use real-world data to examine the healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with PN in patients being treated for MM, comparing those diagnosed with PN to a matched control cohort without PN.

Methods

Study design and data source

This retrospective, observational cohort study was based on administrative healthcare claims data from 1 January 2006 to 28 February 2017 from the IBM® MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare) databases. These databases include inpatient medical, outpatient medical, and outpatient pharmacy claims data, as well as insurance enrollment and demographic information collected from a wide variety of health plans across the US. The Commercial database includes information for over 20 million individuals annually who are under the age of 65 years with employer-sponsored health insurance, including the primary insured, spouses and dependents. The Medicare Supplemental database includes both the Medicare-paid and supplemental-paid components of reimbursed insurance claims information for over 2 million individuals annually with both traditional and supplemental Medicare coverage. The study databases satisfy Sections 164.514 (a)–(b)(1)(ii) of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 privacy rule (HIPAA) regarding the determination and documentation of statistically de-identified data. This study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, and therefore institutional review board approval was not required.

Patient identification

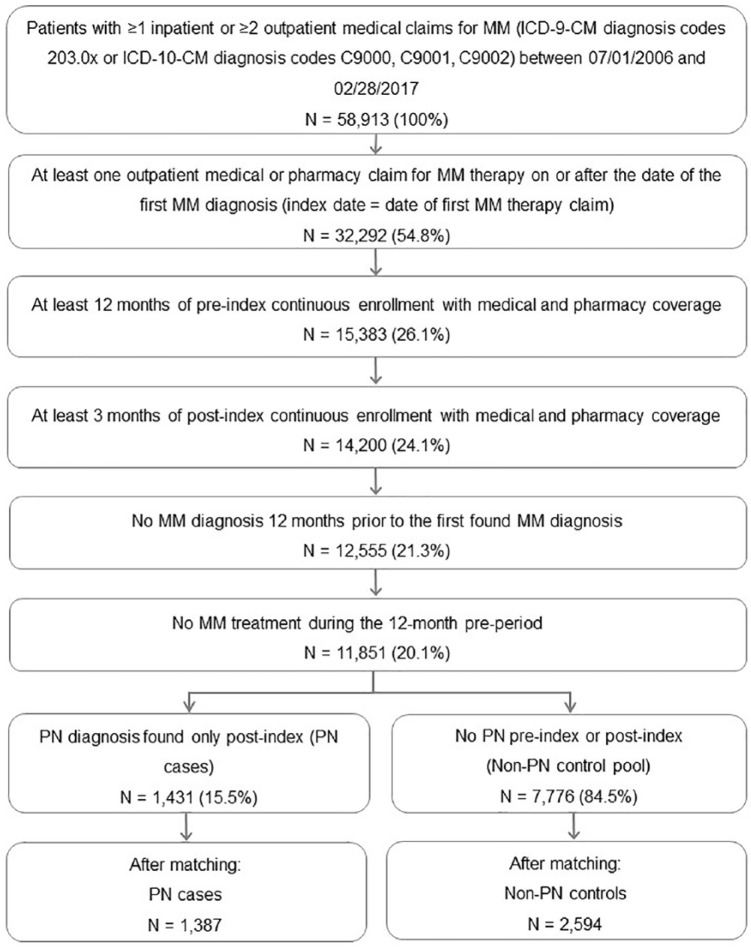

Selected adult patients, 18 years of age and older, had at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims (from 30 to 365 days of the first found outpatient claim) with a diagnosis of MM based on International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes 203.0x or ICD-10-CM (tenth revision) diagnosis codes C9000, C9001 and C9002 between 1 July 2006 and 28 February 2017, and at least one claim indicating the administration or prescription of an MM therapy (bendamustine, bortezomib, carfilzomib, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, doxorubicin liposomal, lenalidomide, melphalan, panobinostat, pomalidomide, thalidomide) on or after the date of the first MM diagnosis. Claims associated with a diagnostic workup such as laboratory tests or diagnostic X-rays were not used for patient selection. To ensure that patients were newly diagnosed and newly treated, a 12-month period with no diagnosis of MM prior to the first found (initial) MM diagnosis and a 12-month period with no MM therapy prior to the initial MM therapy was required. The index date was the date of the first claim for one of the MM therapies on or after the initial MM diagnosis. Continuous medical and prescription coverage was required for at least 12 months prior to the index date (preperiod), and for at least 3 months after the index date (postperiod). Patients were followed from the index date until the earliest evidence of inpatient death (via discharge status), end of continuous enrollment, or end of study period (28 February 2017). This process is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flowchart.

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10-CM, tenth revision; MM, multiple myeloma; PN, peripheral neuropathy.

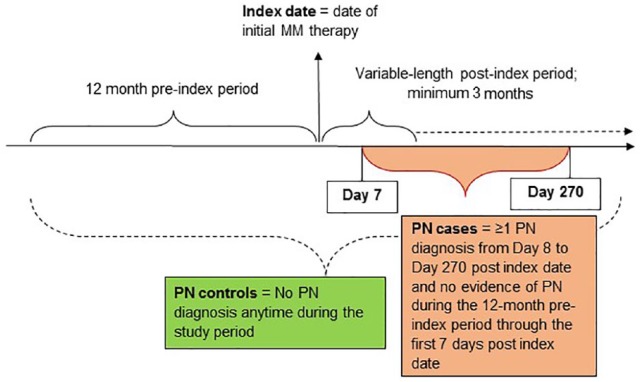

Identification of peripheral neuropathy cases and matched controls

Due to the lack of diagnosis code specificity for disease-related or treatment-induced PN, PN was identified using an algorithm from previously published studies.20,21 PN cases were identified by a medical claim with a diagnosis for PN (codes in Table A.1) during the 9 months following their initial MM therapy and without evidence of PN during the 12-month preperiod through the 7 days following the initial MM treatment (Figure 2). Controls had no medical claims with a diagnosis of PN anytime during the 12-month preperiod and throughout the follow-up period.

Figure 2.

PN definition at the patient level.

MM, multiple myeloma; PN, peripheral neuropathy.

To adjust for imbalances in demographics and clinical characteristics, patients with PN were matched to a pool of patients without PN in a ratio of 1:2 (PN:without PN) using propensity-score modeling with nearest-neighbor matching. Matching factors included patients’ demographic characteristics [age, sex, geographic region of residence, payer (Commercial or Medicare), healthplan type] and baseline clinical characteristics (Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index, DCI)22 and specific preindex comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, skeletal-related events, coagulopathies, hematologic disease, hypertension, and the index MM medication). Standardized differences in matching factors between patients with PN and patients without PN were calculated before and after the matching to examine the quality of the match.

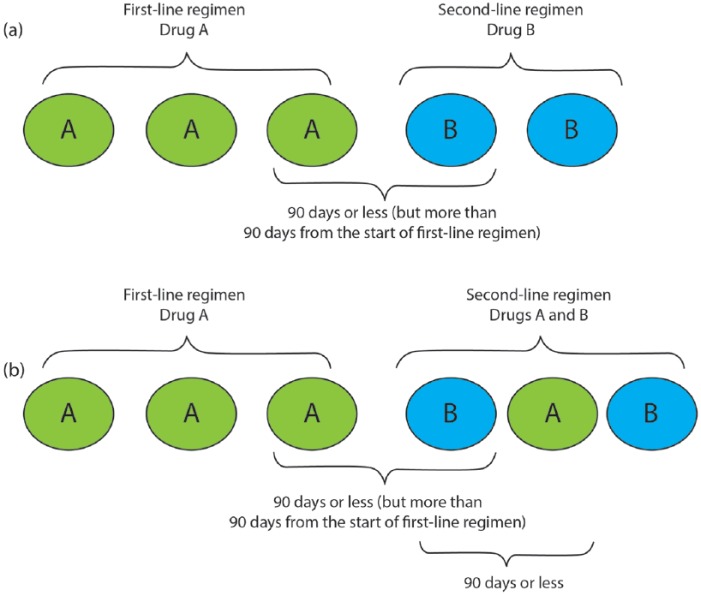

Lines of therapy

This study used a previously published MM treatment algorithm to identify the number of lines of therapy.21 The first line started on the date of the first MM chemotherapy or immunotherapy treatment with bendamustine, bortezomib, carfilzomib, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, doxorubicin liposomal, lenalidomide, melphalan, panobinostat, pomalidomide, or thalidomide. A treatment regimen was defined as consisting of one or more chemotherapy with or without immunotherapy agents administered within 90 days of the start of the line of therapy. A line of therapy ended at the earliest occurrence of a 90-day gap in all MM treatments in a regimen comprising the line of therapy, initiation of a different MM treatment > 90 days after the start of current line of therapy, inpatient discharge status of death, end of enrollment, or end of data. Note that lenalidomide monotherapy initiated within 60 days of the last drug administration in the line of therapy was classified as ‘maintenance therapy’. Maintenance therapy was considered to be a continuation of the line of therapy and not a new line of therapy. Moreover, any MM therapy received within 90 days following a stem-cell transplant date was considered to be ‘consolidation therapy’ within the current line and not the start of a new line of therapy. All subsequent lines of therapy were identified using the same approach as for the first line (with the noted exception above regarding first-line maintenance). Figure 3 describes two examples of changes in treatment regimen and how lines of therapy were defined.

Figure 3.

Examples of switching in regimens.

(a) Switch in treatment regimen; (b) addition to treatment regimen.

Patients with and without PN were identified during each line of therapy. Because of the small number of patients with more than three lines of therapy with PN, the third line and subsequent lines were combined in reporting.

Covariates and study outcomes

Demographics data extracted on the index date, included age, sex, US Census Bureau geographic region, payer (Commercial insurance or Medicare), healthplan type, and index year. Baseline clinical characteristics, measured throughout the 12-month pre-index period, included the DCI (an aggregate measure of comorbidity expressed as a numeric score based on the presence of various diagnoses), specific conditions contained in the DCI, other primary cancers, and other disease-related complications.22

Study outcomes included all-cause healthcare utilization and costs measured during the at-least-3-month follow-up period and stratified for occurrence during the first, second, or third (or higher) lines of therapy. Healthcare utilization and costs were categorized as inpatient medical, emergency department/room (ER), office visits, outpatient hospital-based visits, other outpatient services, and outpatient pharmacy. Due to the variable length of follow up for patients overall and during lines of therapy, healthcare utilization and costs were reported in per-patient-per-month units (PPPM). Costs used the total paid amounts from all payers to all providers, including plan-paid, patient-paid, and coordinated benefit payments. All dollar amounts were inflation adjusted to 2017 US dollars using the Medical Care component of the Consumer Price Index.23

The incidence rate of PN was calculated using the unmatched sample of all treated MM patients as the number of patients with PN divided by the person-time from the index date to the first PN diagnosis for PN patients, plus the person-time from the index date to the end of follow up for patients without PN.

Statistical considerations

Pairwise descriptive statistics were used to compare demographics, comorbid conditions, healthcare utilization and costs between patient cohorts with and without PN after propensity-score matching. Descriptive statistics also evaluated these differences between the comparator cohorts during first line, second line, and third-plus-subsequent lines of therapy. Chi-squared tests were conducted for differences in dichotomous or categorical variables and t tests were conducted for comparisons of continuous variables. A p value < 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistically significant differences. Following propensity-score matching of PN patients and patients without PN, statistically significant postindex differences in results between cohorts were presumed to be associated with the effects of the key independent variable, the incidence of PN. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US).

Results

A total of 9207 patients comprising the case and control pool; 15.5% (1431 patients) were identified as having PN; 7776 had no PN diagnosis anytime during the study period (Figure 1). The incidence rate for a mean (standard deviation) duration of 624 (594) days after an initial MM diagnosis until PN was identified or end of follow up was estimated as 9.1 PN cases per 100 person-years.

Following matching, the study cohorts consisted of 1387 MM patients with PN and 2594 patients without any PN diagnosis during the study period. These matched study cohorts were well balanced with no statistically significant differences in demographics or baseline clinical characteristics (Tables 1). Mean patient age was 64 years, with 60–61% males, and 43–44% covered by Medicare. The length of follow up was longer for PN patients at a mean (SD) of 788 (580) days and 693 (571) days for non-PN patients (Table 1). Among the 1387 MM patients with PN, the mean (SD) and median duration from index date to PN diagnosis was 129 (68) days and 125 days, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics.

| PN cases |

Non-PN controls |

p value | Standard difference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1387 | n = 2594 | ×100* | ||

| Age, mean (SD) years | 63.9 (10.8) | 64.2 (11.6) | 0.314 | 3.39 |

| 18–44 | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.395 | 2.75 |

| 45–54 | 2.7% | 3.7% | 0.084 | 5.89 |

| 55–64 | 16.4% | 15.9% | 0.692 | 1.31 |

| 65–74 | 37.1% | 37.8% | 0.670 | 1.42 |

| 75+ | 25.5% | 20.7% | 0.001 | 11.38 |

| Sex, % | ||||

| Male | 60.6% | 60.1% | 0.725 | 1.17 |

| Female | 39.4% | 39.9% | 0.725 | 1.17 |

| Payer, % | ||||

| Commercial | 55.6% | 57.0% | 0.399 | 2.80 |

| Medicare | 44.4% | 43.0% | 0.399 | 2.80 |

| Insurance plan type, % | ||||

| Preferred-provider organization | 55.7% | 56.2% | 0.740 | 1.10 |

| Comprehensive | 19.6% | 19.0% | 0.623 | 1.63 |

| Health-maintenance organization | 11.6% | 11.7% | 0.945 | 0.23 |

| Point of service | 5.3% | 5.4% | 0.818 | 0.77 |

| Other | 7.9% | 7.7% | 0.867 | 0.55 |

| Geographic region, % | ||||

| Northeast | 17.8% | 17.8% | 0.975 | 0.11 |

| North central | 28.8% | 27.9% | 0.552 | 1.97 |

| South | 35.4% | 37.6% | 0.166 | 4.62 |

| West | 17.2% | 15.3% | 0.114 | 5.22 |

| Unknown | 0.7% | 1.3% | 0.109 | 5.55 |

| Length of follow up, mean (SD) days | 788 (580) | 693 (571) | <0.001 | 16.52 |

| Median follow up (days) | 642 | 522 | ||

| Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.9) | 4.4 (2.8) | 0.999 | 3.69 |

| Comorbid conditions $ | ||||

| Hypertension | 62.5% | 59.9% | 0.109 | 5.34 |

| Skeletal-related events | 48.4% | 48.4% | 0.980 | 0.08 |

| Diabetes | 30.1% | 25.9% | 0.004 | 9.43 |

| Renal disease | 23.0% | 21.0% | 0.155 | 4.71 |

| Ischemic vascular condition‡ | 22.5% | 22.4% | 0.922 | 0.32 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 19.4% | 18.6% | 0.532 | 2.07 |

| Anemia or anemia treatment | 57.0% | 56.1% | 0.569 | 1.89 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 16.4% | 15.4% | 0.435 | 2.59 |

| Hypercalcemia | 14.0% | 13.3% | 0.523 | 2.12 |

| GI bleeding | 5.0% | 5.2% | 0.871 | 0.54 |

| Pneumonia | 9.4% | 9.6% | 0.847 | 0.64 |

| Congestive heart failure | 7.8% | 8.1% | 0.732 | 1.14 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6.8% | 6.6% | 0.860 | 0.59 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 7.8% | 6.9% | 0.282 | 3.55 |

| End-stage renal disease/renal failure | 6.3% | 6.5% | 0.802 | 0.84 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 5.3% | 5.7% | 0.593 | 1.79 |

| Prior primary cancer | ||||

| Solid tumor | 24.4% | 24.0% | 0.805 | 0.82 |

| Hematologic cancer | 12.4% | 13.5% | 0.331 | 3.25 |

| Days from diagnosis to treatment, mean (SD) | 158 (355) | 163 (360) | 0.623 | 1.64 |

| Median (days) | 26 | 27 | ||

| Stem-cell transplant prior to index treatment, % | 0.8% | 1.0% | 0.588 | 1.83 |

| Index MM therapy, % | ||||

| Bendamustine | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.081 | 6.22 |

| Bortezomib | 52.5% | 50.0% | 0.135 | 4.98 |

| Carfilzomib | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.722 | 2.01 |

| Cisplatin | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.902 | 0.41 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 9.9% | 10.3% | 0.733 | 1.14 |

| Doxorubicin | 1.7% | 1.7% | 0.937 | 0.26 |

| Doxorubicin liposomal | 0.2% | 0.2% | 1.000 | 0.32 |

| Lenalidomide | 37.1% | 37.9% | 0.620 | 1.65 |

| Melphalan | 2.1% | 2.8% | 0.190 | 4.45 |

| Panobinostat | 0.0% | 0.0% | – | – |

| Pomalidomide | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1.000 | 0.18 |

| Thalidomide | 4.7% | 5.6% | 0.244 | 3.93 |

GI, gastrointestinal; MM, multiple myeloma; PN, peripheral neuropathy; SD, standard deviation.

The standardized differences were multiplied by 100 to facilitate readers’ viewing results.

Comorbid condition occurring during the preperiod in <5% patients are not shown.

Ischemic vascular conditions include unstable angina, stable angina, ischemic stroke, transient ischemic event, and other chronic ischemic heart disease, including coronary revascularization.

The most common baseline comorbid conditions included hypertension (60–63%), skeletal-related events (48%), diabetes (26–30%), renal disease (21–23%), and ischemic vascular conditions (22%). At index, approximately 50–53% received bortezomib; 37–38% received lenalidomide; 10% received cyclophosphamide, and 5–6% received thalidomide as their initial MM therapy, with the remaining MM therapies received as index medications in less than 3% of patients (Table 1). Of the 3981 matched patients, 1267 (32%) had a PN diagnosis and 2687 (68%) had no PN diagnosis during their first-line therapy. There were 27 patients whose PN diagnosis occurred after the end of the first line but before the start of second-line therapy. A total of 1974 patients had a second-line therapy, of which 280 patients (15%) had PN during their second line, while 1532 patients (85%) had no PN during their second line, with the remaining patients having PN during the first line, thus not eligible for the PN analysis during the second line. Of the 1103 patients with a third or subsequent line of therapy, 75 patients (7%) had a PN diagnosis and 1028 patients (93%) had no PN during their third or subsequent line. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics measured during first-line, second-line, and third/subsequent-line therapy were similar between PN patients and patients without PN (Tables A.2–A.4).

All-cause healthcare utilization

Healthcare utilization was significantly higher in most healthcare use categories among patients with PN compared with patients with no PN. Significantly more PN patients had a hospitalization during follow up (77.4%) compared with patients without PN (67.2%; p < 0.001), however, their length of stay was similar [PN 0.60 (0.87) days PPPM versus non-PN 0.66 (0.96) days PPPM; p = 0.052]. More patients with PN had an ER visit (67.8% versus 58.4%; p < 0.001), had significantly more outpatient hospital-based visits [mean 13.5 (14.7) visits PPPM versus 11.5 (18.0) visits PPPM; p < 0.001], fewer laboratory tests [mean 4.1 (5.1) tests PPPM versus 4.7 (5.6) tests PPPM; p < 0.001], and outpatient prescriptions [4.7 (2.5) prescription claims PPPM versus 4.2 (2.4) prescription claims PPPM; p < 0.001] compared with patients without PN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Per-patient-per-month all-cause healthcare utilization over the entire follow-up period.

| Entire follow-up period |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| PN cases |

Non-PN controls |

p value | |

| n = 1387 | n = 2594 | ||

| All-cause healthcare utilization (PPPM) | |||

| Patients with an inpatient admission, % | 77.4% | 67.2% | <0.001 |

| Admissions PPPM, mean (SD) | 0.11 (0.14) | 0.10 (0.15) | 0.019 |

| Patients with an admission, mean (SD) | 0.14 (0.14) | 0.15 (0.16) | 0.373 |

| Patients with an ER visit, % | 67.8% | 58.4% | <0.001 |

| ER visits PPPM, mean (SD) | 0.13 (0.33) | 0.11 (0.22) | 0.015 |

| Patients with a visit, mean (SD) | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.19 (0.26) | 0.629 |

| Patients with an outpatient office visit, N% | 97.9% | 96.6% | 0.024 |

| Outpatient office visits PPPM, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.2) | 0.142 |

| Patients with a visit, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.1) | 0.342 |

| Patients with outpatient hospital-based visits, % | 98.7% | 96.3% | <0.001 |

| Outpatient hospital-based visits PPPM, mean (SD) | 13.3 (14.7) | 11.1 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Patients with a visit, mean (SD) | 13.5 (14.7) | 11.5 (18.0) | <0.001 |

| Patients with a laboratory test, % | 90.9% | 87.9% | 0.003 |

| Laboratory tests PPPM, mean (SD) | 3.7 (5.0) | 4.1 (5.5) | 0.018 |

| Patients with a test, mean (SD) | 4.1 (5.0) | 4.7 (5.6) | 0.001 |

| Patients filling an outpatient prescription, % | 97.2% | 97.1% | 0.941 |

| Outpatient prescriptions PPPM, mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.6) | 4.0 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Patients with a prescription, mean (SD) | 4.7 (2.5) | 4.2 (2.4) | <0.001 |

ER, emergency department (room); PN, peripheral neuropathy; PPPM, per patient per month; SD, standard deviation.

Use of narcotic pain medication was common and also higher among patients with PN compared with patients with no PN (during first-line therapy: 82% versus 72%; p < 0.001).

All-cause healthcare costs

Healthcare costs were also higher among patients with PN compared with control patients with no PN and increased as patients proceeded to higher lines of therapy (Table 3). Mean total costs for PN patients exceeded those of patients without PN by $1509 PPPM [PN $16,600 (SD $14,450) versus non-PN $15,090 (SD $13,399); p = 0.001] over the entire follow-up period. This difference was primarily attributable to the first 180 days postindex, where PN patients’ mean PPPM costs exceeded those of the non-PN cohort by $3317 during the first 90 days (p < 0.001), and by $5167 during the period 91–180 days postindex (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Per-patient-per-month all-cause healthcare costs over the entire follow-up period.

| Entire follow-up period |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| PN cases |

Non-PN controls |

p value | |

| n = 1387 | n = 2594 | ||

| All-cause healthcare costs (PPPM) | |||

| Inpatient-admission costs, mean (SD) | $4750 ($9944) | $4002 ($8993) | 0.016 |

| Outpatient medical costs, mean (SD) | $8100 ($8,341) | $7408 ($8,007) | 0.010 |

| ER costs, mean (SD) | $126 ($620) | $92 ($374) | 0.029 |

| Outpatient office-visit costs, mean (SD) | $216 ($302) | $203 ($329) | 0.214 |

| Outpatient hospital-based visit costs, mean (SD) | $4906 ($6410) | $4076 ($6280) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory-testing costs, mean (SD) | $144 ($309) | $140 ($290) | 0.687 |

| Outpatient prescription costs, mean (SD) | $3749 ($3312) | $3681 ($3596) | 0.555 |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $16,600 ($14,450) | $15,090 ($13,399) | 0.001 |

| Quarterly healthcare costs (PPPM) | |||

| 0–90 days postindex, n | 1381 | 2583 | |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $22,777 ($19,074) | $19,460 ($16,064) | <0.001 |

| 91–180 days postindex, n | 1299 | 2286 | |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $24,402 ($24,760) | $19,235 ($19,769) | <0.001 |

| 181–270 days postindex, n | 1168 | 1986 | |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $15,766 ($21,032) | $14,052 ($18,286) | 0.008 |

| 271–360 days postindex, n | 1026 | 1682 | |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $11,955 ($15,774) | $11,518 ($15,756) | 0.404 |

ER, emergency department (room); PN, peripheral neuropathy; PPPM, per patient per month; SD, standard deviation.

Table 4 contrasts the PPPM costs for patients who had a PN diagnosis during a particular line of therapy with patients who did not have a PN diagnosis during that same line. The PN patients’ total costs were significantly higher during the first line of therapy ($23,183 (SD $22,243) versus $20,790 (SD $27,748); p = 0.007) and second line ($37,880 (SD $58,007) versus $29,694 (SD $103,457); p = 0.198) compared with patients without a PN diagnosis during those lines. This difference was primarily driven by outpatient medical costs, and particularly by outpatient hospital-based visits.

Table 4.

Per-patient-per-month all-cause healthcare costs by line of therapy stratified by patients with and without PN.

| Line of therapy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line therapy |

|||

| PN in first line |

No PN first line |

p value | |

| n = 1267 | n = 2687 | ||

| Inpatient-admission costs, mean (SD) | $6158 ($18,095) | $5000 ($24,001) | 0.127 |

| Outpatient medical costs, mean (SD) | $12,598 ($11,306) | $10,949 ($11,319) | <0.001 |

| ER costs, mean (SD) | $180 ($798) | $129 ($766) | 0.055 |

| Outpatient office-visit costs, mean (SD) | $318 ($659) | $281 ($522) | 0.062 |

| Outpatient hospital-based visits, mean (SD) | $7687 ($10,244) | $6049 ($9927) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory-testing costs, mean (SD) | $212 ($552) | $197 ($454) | 0.376 |

| Outpatient prescription costs, mean (SD) | $4427 ($4103) | $4841 ($6715) | 0.043 |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $23,183 ($22,243) | $20,790 ($27,748) | 0.007 |

| Second-line therapy |

|||

| PN second line |

No PN second line |

p value | |

| n = 280 | n = 1532 | ||

| Inpatient-admission costs, mean (SD) | $15,726 ($51,561) | $11,468 ($99,972) | 0.487 |

| Outpatient medical costs, mean (SD) | $15,807 ($22,951) | $11,277 ($18,854) | <0.001 |

| ER costs, mean (SD) | $271 ($2811) | $133 ($879) | 0.119 |

| Outpatient office-visit costs, mean (SD) | $244 ($325) | $240 ($483) | 0.889 |

| Outpatient hospital-based visits, mean (SD) | $11,250 ($21,747) | $7176 ($17,414) | 0.001 |

| Laboratory-testing costs, mean (SD) | $173 ($546) | $149 ($441) | 0.428 |

| Outpatient prescription costs, mean (SD) | $6348 ($6,192) | $6950 ($9282) | 0.297 |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $37,880 ($58,007) | $29,694 ($103,457) | 0.198 |

| Third and subsequent lines of

therapy |

|||

| PN third+ line |

No PN third+ line |

p value | |

| n = 75 | n = 1028 | ||

| Inpatient-admission costs, mean (SD) | $7228 ($19,480) | $6488 ($27,591) | 0.820 |

| Outpatient medical costs, mean (SD) | $9803 ($12,438) | $10,563 ($15,657) | 0.681 |

| ER costs, mean (SD) | $148 ($347) | $126 ($784) | 0.812 |

| Outpatient office-visit costs, mean (SD) | $235 ($256) | $224 ($351) | 0.787 |

| Outpatient hospital-based visits, mean (SD) | $7414 ($11,805) | $6240 ($13,760) | 0.472 |

| Laboratory-testing costs, mean (SD) | $70 ($174) | $147 ($440) | 0.132 |

| Outpatient prescription costs, mean (SD) | $8563 ($7307) | $7777 ($11,021) | 0.543 |

| Total costs, mean (SD) | $25,594 ($26,656) | $24,827 ($34,532) | 0.851 |

ER, emergency department (room); PN, peripheral neuropathy; PPPM, per patient per month; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

This study found significantly higher healthcare resource utilization and costs in patients with a post-treatment diagnosis for PN during their follow up compared with a matched group of patients without PN. Patients with PN were significantly more likely to be hospitalized, had an ER visit, had an outpatient hospital-based visit, and filled more outpatient prescriptions than matched patients without a PN diagnosis. This increased use of healthcare resource was associated with $1509 higher PPPM total costs, amounting to $36,216 over PN patients’ mean 2-year follow-up time. Pike and colleagues, in a similar study using administrative US claims data (1999–2006), estimated the costs for chemotherapy-induced PN in a matched cohort comparison of cancer patients (not MM) with and without post-treatment PN, finding that PN patients had higher mean total healthcare costs by $17,344 during the 12-month study period than comparable patients without PN. They further found that more PN cases were hospitalized, had an ER visit, and had other outpatient visits.24 In a 2001 pilot study of chemotherapy-induced toxicity in ovarian cancer patients, Calhoun and colleagues found indirect costs, such as the cost of caregiver time and lost wages, to be a substantial contributor to the total burden of chemotherapy-induced toxicity.25 The estimated marginal healthcare expenditure of $1509 PPPM attributable to PN in our study using direct medical and prescription expenditures derived from paid healthcare claims represents only a portion of the overall societal cost. Due to the lack of information, costs associated with caregiver burden, indirect costs, or the quality of life impact were not examined.

In our study, the rate of PN in MM patients was 15.5%, which appears low compared with other studies where PN rates ranged from over 20% to as high as 70%15,16,26,27 This may be attributable to several contributing factors. The diagnosis of PN may be under-reported in claims, as healthcare providers may only include the diagnosis when the presentation of PN is severe or substantially affecting disease management. Patients expecting drug side effects may not seek treatment for mild PN. This was confirmed by the finding of Yong et al. using chart review data. Yong and colleagues found that although more than 45% of MM patients had PN, less than 4% had grade 3 or 4 PN during the first four lines of therapy.27 Clinical trials have also reported a much lower PN rate of grade 3–4 than PN rate of grade 1–2.16 Some patients indexing in the latter years of the study may have experienced PN after the end of their available data. The incidence rate reported in our study of 9.1 PN cases per 100 person-years may likewise reflect a similar underestimate. In addition, it was estimated that 3.2% of MM patients have baseline PN.21 In the current study, patients with baseline PN who later had another PN diagnosis post-treatment were excluded from the PN rate calculation, which may further lower the estimated PN rate. This exclusion was applied so as not to overestimate PN.

Our cohorts were demographically similar to the US MM population in terms of age and sex based on the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program’s reporting most patients diagnosed between 65 and 74 years of age, median age 69 at initial diagnosis, and the SEER and American Cancer Society’s estimate of 59% male–41% female incidence. The population in this study is slightly younger overall due to larger representation from commercial carriers than from Medicare data providers.1,2

Obtaining optimal clinical efficacy requires carefully balancing treatment effectiveness with the potential for negative consequences on the patient’s quality of life. The dosage reductions, treatment switches, or discontinuation of MM therapies to manage PN may ultimately affect response to therapy.28 Thalidomide and bortezomib are associated with higher rates of PN.12,13,15,16 Recent approval of novel therapies29–32 hold promise for antimyeloma efficacy with reduced incidence of PN.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with this study. Use of diagnosis coding from administrative claims data may be subject to misclassification errors, where the extent of undercoding for the selected conditions or comorbidities is unknown, and without the availability of patient charts or physician attestations. PN diagnoses may not be included on administrative claims unless the impairment significantly affects patient management, thereby under-reported or biased toward more severe cases. PN could not be identified directly in claims data because of the lack of diagnosis codes specific to disease-related and treatment-induced PN. Consequently, PN identification used an algorithm from a previously published study that has not been validated, and the PN could be due to other causes. This study used propensity-score matching to ensure cohorts had similar baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, increasing the likelihood that differences between cohorts were associated with PN. However, there is always the potential of unmeasured confounders outside of this study’s data sources. In addition, the incremental healthcare utilization and costs in the PN cohort may not be directly linked to PN; it could also be due to PN treatment, PN complications, and other conditions that could not be controlled or adjusted for in the claims data. Pharmacological treatments that were based on pharmacy prescription claims only indicated that prescriptions were received, not necessarily how the patients took the medications. This is not an issue for medications administered in the physician’s office and billed through a medical claim. Several drugs (carfilzomib, pomalidomide, panobinostat) entered the US market more recently (since 2012), resulting in limited sample sizes for these agents, so PN rates specific to individual medications were not examined. MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare databases are convenience samples of employees, retirees, and dependents with US Commercial and Medicare health-insurance coverage, therefore results from these databases may not be generalizable to populations with other healthcare coverage (e.g. Medicaid), or those lacking coverage.

Conclusion

PN was observed in 15.5% of MM patients, and was associated with a significant economic burden, adding an average of $1509 monthly per patient to the cost of MM treatment, as well as adding to the complexity of treatment with detrimental impact to patients. These results suggest that utilization of newer, more effective novel treatments might ease the economic and disease burden for MM associated with PN.

Acknowledgments

Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Jay Margolis, an employee of IBM Watson Health.

Appendix

Table A.1.

ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes of peripheral neuropathy.

| ICD-9-CM diagnosis code | Description |

|---|---|

| 337.20 | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, unspecified |

| 337.21 | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the upper limb |

| 337.22 | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the lower limb |

| 337.29 | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of other specified site |

| 353.0 | Brachial plexus lesions |

| 353.2 | Cervical root lesions, not elsewhere classified |

| 353.4 | Lumbosacral root lesions, not elsewhere classified |

| 355.71 | Causalgia of lower limb |

| 355.79 | Other mononeuritis of lower limb |

| 355.9 | Mononeuritis of unspecified site |

| 357.0 | Acute infective polyneuritis |

| 357.1 | Polyneuropathy in collagen vascular disease |

| 357.2 | Polyneuropathy in diabetes |

| 357.3 | Polyneuropathy in malignant disease |

| 357.4 | Polyneuropathy in other diseases classified elsewhere |

| 357.5 | Alcoholic polyneuropathy |

| 357.6 | Polyneuropathy due to drugs |

| 357.7 | Polyneuropathy due to other toxic agents |

| 357.81 | Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuritis |

| 357.82 | Critical illness polyneuropathy |

| 357.89 | Other inflammatory and toxic neuropathy |

| 357.9 | Unspecified inflammatory and toxic neuropathies |

| 377.34 | Toxic optic neuropathy |

| 729.2 | Neuralgia, neuritis, and radiculitis, unspecified |

| 782.0 | Disturbance of skin sensation |

| ICD-10-CM diagnosis code | Code description |

| G9050 | Complex regional pain syndrome I, unspecified |

| G90513 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of upper limb, bilateral |

| G90511 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of right upper limb |

| G90512 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of left upper limb |

| G90519 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of unspecified upper limb |

| G90521 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of right lower limb |

| G90529 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of unspecified lower limb |

| G90522 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of left lower limb |

| G90523 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of lower limb, bilateral |

| G9059 | Complex regional pain syndrome I of other specified site |

| G540 | Brachial plexus disorders |

| G55 | Nerve root and plexus compressions in diseases classified elsewhere |

| G542 | Cervical root disorders, not elsewhere classified |

| G544 | Lumbosacral root disorders, not elsewhere classified |

| E0841 | Diabetes mellitus due to underlying condition with diabetic mononeuropathy |

| E0941 | Drug or chemical-induced diabetes mellitus with neurological complications with diabetic mononeuropathy |

| E1041 | Type 1 diabetes mellitus with diabetic mononeuropathy |

| E1141 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic mononeuropathy |

| E1341 | Other specified diabetes mellitus with diabetic mononeuropathy |

| G5770 | Causalgia of unspecified lower limb |

| G5771 | Causalgia of right lower limb |

| G5772 | Causalgia of left lower limb |

| G5773 | Causalgia of bilateral lower limbs |

| G59 | Mononeuropathy in diseases classified elsewhere |

| G5780 | Other specified mononeuropathies of unspecified lower limb |

| G5781 | Other specified mononeuropathies of right lower limb |

| G5782 | Other specified mononeuropathies of left lower limb |

| G5783 | Other specified mononeuropathies of bilateral lower limbs |

| G588 | Other specified mononeuropathies |

| G589 | Mononeuropathy, unspecified |

| G64 | Other disorders of peripheral nervous system |

| G610 | Guillain–Barré syndrome |

| M0550 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified site |

| M05511 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right shoulder |

| M05512 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left shoulder |

| M05519 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified shoulder |

| M05521 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right elbow |

| M05522 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left elbow |

| M05529 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified elbow |

| M05531 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right wrist |

| M05532 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left wrist |

| M05539 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified wrist |

| M05541 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right hand |

| M05542 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left hand |

| M05549 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified hand |

| M05551 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right hip |

| M05552 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left hip |

| M05559 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified hip |

| M05561 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right knee |

| M05562 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left knee |

| M05569 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified knee |

| M05571 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of right ankle and foot |

| M05572 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of left ankle and foot |

| M05579 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of unspecified ankle and foot |

| M0559 | Rheumatoid polyneuropathy with rheumatoid arthritis of multiple sites |

| E0840 | Diabetes mellitus due to underlying condition with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified |

| E0842 | Diabetes mellitus due to underlying condition with diabetic polyneuropathy |

| E0940 | Drug or chemical-induced diabetes mellitus with neurological complications with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified |

| E0942 | Drug or chemical-induced diabetes mellitus with neurological complications with diabetic polyneuropathy |

| E1040 | Type 1 diabetes mellitus with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified |

| E1042 | Type 1 diabetes mellitus with diabetic polyneuropathy |

| E1140 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified |

| E1142 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic polyneuropathy |

| E1340 | Other specified diabetes mellitus with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified |

| E1342 | Other specified diabetes mellitus with diabetic polyneuropathy |

| G130 | Paraneoplastic neuromyopathy and neuropathy |

| G131 | Other systemic atrophy primarily affecting central nervous system in neoplastic disease |

| A3683 | Diphtheritic polyneuritis |

| A5215 | Late syphilitic neuropathy |

| G63 | Polyneuropathy in diseases classified elsewhere |

| M3483 | Systemic sclerosis with polyneuropathy |

| G621 | Alcoholic polyneuropathy |

| G611 | Serum neuropathy |

| G620 | Drug-induced polyneuropathy |

| G622 | Polyneuropathy due to other toxic agents |

| G6282 | Radiation-induced polyneuropathy |

| G6181 | Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuritis |

| G6281 | Critical illness polyneuropathy |

| G6189 | Other inflammatory polyneuropathies |

| G6289 | Other specified polyneuropathies |

| G619 | Inflammatory polyneuropathy, unspecified |

| G629 | Polyneuropathy, unspecified |

| H463 | Toxic optic neuropathy |

| M5410 | Radiculopathy, site unspecified |

| M5418 | Radiculopathy, sacral and sacrococcygeal region |

| M792 | Neuralgia and neuritis, unspecified |

| R200 | Anesthesia of skin |

| R201 | Hypoesthesia of skin |

| R202 | Paresthesia of skin |

| R203 | Hyperesthesia |

| R208 | Other disturbances of skin sensation |

| R209 | Unspecified disturbances of skin sensation |

ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10, tenth revision.

Table A.2.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of first-line therapy.

| Demographic characteristics | First-line therapy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With PN |

Without PN |

p value | |||

|

n = 1267 |

n = 2687 |

||||

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 64.0 | 10.81 | 64.2 | 11.61 | 0.661 |

| Age group (n, %) | |||||

| 18–34 | 4 | 0.3% | 9 | 0.3% | 1.000 |

| 35–44 | 36 | 2.8% | 95 | 3.5% | 0.255 |

| 45–54 | 204 | 16.1% | 429 | 16.0% | 0.914 |

| 55–64 | 459 | 36.2% | 1021 | 38.0% | 0.283 |

| 65–74 | 333 | 26.3% | 555 | 20.7% | 0.000 |

| 75+ | 231 | 18.2% | 578 | 21.5% | 0.017 |

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Male | 761 | 60.1% | 1621 | 60.3% | 0.874 |

| Female | 506 | 39.9% | 1066 | 39.7% | 0.874 |

| Payer (n, %) | |||||

| Commercial | 690 | 54.5% | 1536 | 57.2% | 0.110 |

| Medicare | 577 | 45.5% | 1151 | 42.8% | 0.110 |

| Insurance plan type (n, %) | |||||

| Comprehensive | 259 | 20.4% | 503 | 18.7% | 0.200 |

| Exclusive-provider organization | 4 | 0.3% | 19 | 0.7% | 0.131 |

| Health-maintenance organization | 141 | 11.1% | 321 | 11.9% | 0.455 |

| Point of service (POS) | 66 | 5.2% | 147 | 5.5% | 0.734 |

| Preferred-provider organization | 704 | 55.6% | 1508 | 56.1% | 0.742 |

| POS with capitation | 8 | 0.6% | 14 | 0.5% | 0.663 |

| Consumer-driven healthplan | 60 | 4.7% | 116 | 4.3% | 0.552 |

| High-deductible healthplan | 25 | 2.0% | 59 | 2.2% | 0.651 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Geographic region (n, %) | |||||

| Northeast | 217 | 17.1% | 488 | 18.2% | 0.428 |

| North central | 372 | 29.4% | 744 | 27.7% | 0.276 |

| South | 448 | 35.4% | 1011 | 37.6% | 0.168 |

| West | 221 | 17.4% | 410 | 15.3% | 0.080 |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.7% | 34 | 1.3% | 0.116 |

| Population density (n, %) | |||||

| Urban | 1086 | 85.7% | 2276 | 84.7% | 0.406 |

| Rural | 172 | 13.6% | 379 | 14.1% | 0.654 |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.7% | 32 | 1.2% | 0.164 |

| Duration of line of therapy (mean, SD) | 234.9 | 219.9 | 244.6 | 241.2 | 0.222 |

| DCI (mean, SD) | 4.5 | 2.84 | 4.5 | 2.86 | 0.581 |

| DCI (n, %) | |||||

| 0 | 11 | 0.9% | 21 | 0.8% | 0.777 |

| 1 | 12 | 0.9% | 13 | 0.5% | 0.086 |

| 2 | 402 | 31.7% | 900 | 33.5% | 0.270 |

| 3+ | 842 | 66.5% | 1753 | 65.2% | 0.452 |

| DCI components (n, %) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 46 | 3.6% | 87 | 3.2% | 0.523 |

| Congestive heart failure | 100 | 7.9% | 217 | 8.1% | 0.843 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 53 | 4.2% | 112 | 4.2% | 0.983 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 87 | 6.9% | 179 | 6.7% | 0.810 |

| Dementia | 2 | 0.2% | 7 | 0.3% | 0.727 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 206 | 16.3% | 417 | 15.5% | 0.551 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 30 | 2.4% | 60 | 2.2% | 0.791 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 19 | 1.5% | 50 | 1.9% | 0.418 |

| Mild liver disease | 10 | 0.8% | 15 | 0.6% | 0.392 |

| Diabetes (mild to moderate) | 286 | 22.6% | 561 | 20.9% | 0.225 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 93 | 7.3% | 144 | 5.4% | 0.014 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 5 | 0.4% | 11 | 0.4% | 0.946 |

| Renal disease | 285 | 22.5% | 573 | 21.3% | 0.405 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 2 | 0.2% | 5 | 0.2% | 1.000 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 3 | 0.2% | 6 | 0.2% | 1.000 |

| Any malignancy, including lymphoma and leukemia | 1094 | 86.3% | 2339 | 87.0% | 0.542 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 190 | 15.0% | 417 | 15.5% | 0.670 |

| Prior primary cancer (n, %) | |||||

| Solid tumor | 309 | 24.4% | 647 | 24.1% | 0.832 |

| Hematologic cancer | 157 | 12.4% | 363 | 13.5% | 0.332 |

| Preperiod events of interest (n, %) | |||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 243 | 19.2% | 503 | 18.7% | 0.730 |

| End-stage renal disease/renal failure | 84 | 6.6% | 170 | 6.3% | 0.717 |

| Skeletal-related events | 610 | 48.1% | 1303 | 48.5% | 0.838 |

| Hypercalcemia | 172 | 13.6% | 361 | 13.4% | 0.904 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 52 | 4.1% | 120 | 4.5% | 0.603 |

| Neutropenia | 42 | 3.3% | 93 | 3.5% | 0.813 |

| Pneumonia | 123 | 9.7% | 251 | 9.3% | 0.713 |

| Major bleeding | 26 | 2.1% | 52 | 1.9% | 0.805 |

| GI bleeding | 63 | 5.0% | 141 | 5.2% | 0.715 |

| Anemia | 718 | 56.7% | 1504 | 56.0% | 0.681 |

| Anemia or anemia treatment | 720 | 56.8% | 1514 | 56.3% | 0.776 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 95 | 7.5% | 188 | 7.0% | 0.568 |

| Amyloidosis | 49 | 3.9% | 88 | 3.3% | 0.342 |

DCI, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index; GI, gastrointestinal; PN, peripheral neuropathy; SD, standard deviation.

Table A.3.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of second-line therapy.

| Demographic characteristics | Second-line therapy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With PN |

Without PN |

p value | |||

|

n = 280 |

n = 1532 |

||||

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 62.8 | 10.35 | 62.3 | 11.09 | 0.418 |

| Age group (n, %) | |||||

| 18–34 | 4 | 1.4% | 6 | 0.4% | 0.054 |

| 35–44 | 5 | 1.8% | 60 | 3.9% | 0.078 |

| 45–54 | 47 | 16.8% | 309 | 20.2% | 0.190 |

| 55–64 | 110 | 39.3% | 617 | 40.3% | 0.756 |

| 65–74 | 74 | 26.4% | 281 | 18.3% | 0.002 |

| 75+ | 40 | 14.3% | 259 | 16.9% | 0.277 |

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Male | 178 | 63.6% | 926 | 60.4% | 0.324 |

| Female | 102 | 36.4% | 606 | 39.6% | 0.324 |

| Payer (n, %) | |||||

| Commercial | 164 | 58.6% | 981 | 64.0% | 0.081 |

| Medicare | 116 | 41.4% | 551 | 36.0% | 0.081 |

| Insurance plan type (n, %) | |||||

| Comprehensive | 46 | 16.4% | 260 | 17.0% | 0.824 |

| Exclusive-provider organization | 2 | 0.7% | 16 | 1.0% | 1.000 |

| Health-maintenance organization | 43 | 15.4% | 188 | 12.3% | 0.155 |

| Point of service (POS) | 17 | 6.1% | 96 | 6.3% | 0.901 |

| Preferred-provider organization | 150 | 53.6% | 854 | 55.7% | 0.501 |

| POS with capitation | 2 | 0.7% | 9 | 0.6% | 0.682 |

| Consumer-driven health plan | 12 | 4.3% | 76 | 5.0% | 0.629 |

| High-deductible health plan | 8 | 2.9% | 33 | 2.2% | 0.467 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Geographic region (n, %) | |||||

| Northeast | 51 | 18.2% | 256 | 16.7% | 0.537 |

| North central | 70 | 25.0% | 431 | 28.1% | 0.281 |

| South | 107 | 38.2% | 582 | 38.0% | 0.943 |

| West | 50 | 17.9% | 249 | 16.3% | 0.506 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.7% | 14 | 0.9% | 1.000 |

| Population density (n, %) | |||||

| Urban | 242 | 86.4% | 1,294 | 84.5% | 0.400 |

| Rural | 36 | 12.9% | 224 | 14.6% | 0.439 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.7% | 14 | 0.9% | 1.000 |

| Duration of line of therapy (mean, SD) | 171.2 | 199.7 | 201.0 | 249.9 | 0.059 |

| DCI (mean, SD) | 4.7 | 2.95 | 4.3 | 2.78 | 0.03 |

| DCI (n, %) | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 0.4% | 18 | 1.2% | 0.340 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.4% | 8 | 0.5% | 1.000 |

| 2 | 96 | 34.3% | 547 | 35.7% | 0.648 |

| 3+ | 182 | 65.0% | 959 | 62.6% | 0.444 |

| DCI components (n, %) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 3.9% | 43 | 2.8% | 0.310 |

| Congestive heart failure | 16 | 5.7% | 92 | 6.0% | 0.850 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7 | 2.5% | 53 | 3.5% | 0.409 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 19 | 6.8% | 92 | 6.0% | 0.617 |

| Dementia | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 0.3% | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 44 | 15.7% | 225 | 14.7% | 0.657 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 3 | 1.1% | 32 | 2.1% | 0.255 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 7 | 2.5% | 28 | 1.8% | 0.452 |

| Mild liver disease | 1 | 0.4% | 6 | 0.4% | 1.000 |

| Diabetes (mild to moderate) | 66 | 23.6% | 311 | 20.3% | 0.215 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 20 | 7.1% | 70 | 4.6% | 0.068 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 0.6% | |

| Renal disease | 73 | 26.1% | 334 | 21.8% | 0.115 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.1% | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.4% | |

| Any malignancy, including lymphoma and leukemia | 247 | 88.2% | 1,434 | 93.6% | 0.001 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 50 | 17.9% | 244 | 15.9% | 0.421 |

| Prior primary cancer (n, %) | |||||

| Solid tumor | 59 | 21.1% | 325 | 21.2% | 0.957 |

| Hematologic cancer | 40 | 14.3% | 189 | 12.3% | 0.367 |

| Preperiod events of interest (n, %) | |||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 59 | 21.1% | 250 | 16.3% | 0.052 |

| End-stage renal disease/renal failure | 14 | 5.0% | 76 | 5.0% | 0.978 |

| Skeletal-related events | 138 | 49.3% | 738 | 48.2% | 0.732 |

| Hypercalcemia | 41 | 14.6% | 222 | 14.5% | 0.947 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 13 | 4.6% | 64 | 4.2% | 0.723 |

| Neutropenia | 7 | 2.5% | 50 | 3.3% | 0.501 |

| Pneumonia | 22 | 7.9% | 129 | 8.4% | 0.754 |

| Major bleeding | 5 | 1.8% | 22 | 1.4% | 0.595 |

| GI bleeding | 15 | 5.4% | 77 | 5.0% | 0.817 |

| Anemia | 163 | 58.2% | 825 | 53.9% | 0.178 |

| Anemia or anemia treatment | 163 | 58.2% | 829 | 54.1% | 0.205 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 29 | 10.4% | 100 | 6.5% | 0.022 |

| Amyloidosis | 10 | 3.6% | 34 | 2.2% | 0.177 |

DCI, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index; GI, gastrointestinal; PN, peripheral neuropathy; SD, standard deviation.

Table A.4.

| Demographic characteristics | Third and subsequent line of

therapy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With PN |

Without PN |

p value | |||

|

n = 75 |

n = 1028 |

||||

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 62.0 | 9.57 | 61.2 | 10.72 | 0.517 |

| Age group (n, %) | |||||

| 18–34 | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 0.7% | |

| 35–44 | 2 | 2.7% | 44 | 4.3% | 0.764 |

| 45–54 | 14 | 18.7% | 227 | 22.1% | 0.490 |

| 55–64 | 31 | 41.3% | 408 | 39.7% | 0.779 |

| 65–74 | 19 | 25.3% | 210 | 20.4% | 0.312 |

| 75+ | 9 | 12.0% | 132 | 12.8% | 0.833 |

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Male | 50 | 66.7% | 617 | 60.0% | 0.256 |

| Female | 25 | 33.3% | 411 | 40.0% | 0.256 |

| Payer (n, %) | |||||

| Commercial | 45 | 60.0% | 671 | 65.3% | 0.356 |

| Medicare | 30 | 40.0% | 357 | 34.7% | 0.356 |

| Insurance plan type (n, %) | |||||

| Comprehensive | 11 | 14.7% | 176 | 17.1% | 0.585 |

| Exclusive-provider organization | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Health-maintenance organization | 9 | 12.0% | 130 | 12.6% | 0.871 |

| Point of service (POS) | 7 | 9.3% | 74 | 7.2% | 0.494 |

| Preferred-provider organization | 42 | 56.0% | 547 | 53.2% | 0.640 |

| POS with capitation | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 0.5% | |

| Consumer-driven health plan | 4 | 5.3% | 66 | 6.4% | 1.000 |

| High-deductible health plan | 2 | 2.7% | 23 | 2.2% | 0.685 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Geographic region (n, %) | |||||

| Northeast | 11 | 14.7% | 188 | 18.3% | 0.431 |

| North central | 13 | 17.3% | 283 | 27.5% | 0.054 |

| South | 30 | 40.0% | 356 | 34.6% | 0.347 |

| West | 21 | 28.0% | 195 | 19.0% | 0.057 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.6% | |

| Population density (n, %) | |||||

| Urban | 64 | 85.3% | 900 | 87.5% | 0.577 |

| Rural | 11 | 14.7% | 122 | 11.9% | 0.472 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.6% | 0.507 |

| Duration of line of therapy (mean, SD) | 244.0 | 275.6 | 196.2 | 239.1 | 0.099 |

| DCI (mean, SD) | 4.3 | 2.84 | 4.0 | 2.55 | 0.274 |

| DCI (n, %) | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 15 | 1.5% | 0.292 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | NA |

| 2 | 29 | 38.7% | 399 | 38.8% | 0.98 |

| 3+ | 46 | 61.3% | 614 | 59.7% | 0.784 |

| DCI components (n, %) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 1.6% | |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 | 2.7% | 32 | 3.1% | 1.000 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3 | 4.0% | 27 | 2.6% | 0.452 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 | 8.0% | 66 | 6.4% | 0.625 |

| Dementia | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 12 | 16.0% | 150 | 14.6% | 0.739 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 2 | 2.7% | 13 | 1.3% | 0.272 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 1.6% | |

| Mild liver disease | 3 | 4.0% | 4 | 0.4% | 0.009 |

| Diabetes (mild to moderate) | 13 | 17.3% | 210 | 20.4% | 0.519 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 2 | 2.7% | 54 | 5.3% | 0.581 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 1 | 1.3% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.131 |

| Renal disease | 14 | 18.7% | 218 | 21.2% | 0.602 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Any malignancy, including lymphoma and leukemia | 74 | 98.7% | 1000 | 97.3% | 0.716 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 13 | 17.3% | 140 | 13.6% | 0.369 |

| Prior primary cancer (n, %) | |||||

| Solid tumor | 19 | 25.3% | 215 | 20.9% | 0.366 |

| Hematologic cancer | 11 | 14.7% | 125 | 12.2% | 0.524 |

| Preperiod events of interest (n, %) | |||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 | 14.7% | 168 | 16.3% | 0.704 |

| End-stage renal disease/renal failure | 2 | 2.7% | 48 | 4.7% | 0.573 |

| Skeletal-related events | 42 | 56.0% | 486 | 47.3% | 0.144 |

| Hypercalcemia | 10 | 13.3% | 115 | 11.2% | 0.571 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1 | 1.3% | 38 | 3.7% | 0.512 |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 2.7% | 28 | 2.7% | 1.000 |

| Pneumonia | 5 | 6.7% | 84 | 8.2% | 0.644 |

| Major bleeding | 2 | 2.7% | 13 | 1.3% | 0.272 |

| GI bleeding | 3 | 4.0% | 46 | 4.5% | 1.000 |

| Anemia | 36 | 48.0% | 550 | 53.5% | 0.357 |

| Anemia or anemia treatment | 36 | 48.0% | 554 | 53.9% | 0.323 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 7 | 9.3% | 62 | 6.0% | 0.224 |

| Amyloidosis | 0 | 0.0% | 18 | 1.8% | 0.248 |

DCI, Deyo–Charlson Comorbidity Index; GI, gastrointestinal; NA, not applicaple; PN, peripheral neuropathy; SD, standard deviation.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was sponsored by Amgen, Inc.

Conflict of interest statement: Xue Song, Kathleen Wilson, and Jerry Kagan are employees of IBM Watson Health, which received funding from Amgen, Inc. to conduct this analysis. Sumeet Panjabi is an employee and stockholder of Amgen Inc.

ORCID iD: Xue Song  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7186-176X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7186-176X

Contributor Information

Xue Song, IBM Watson Health, 75 Binney Street, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA.

Kathleen L. Wilson, IBM Watson Health, Cambridge, MA, USA

Jerry Kagan, IBM Watson Health, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Sumeet Panjabi, Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

References

- 1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2011. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2014, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/ (accessed 14 March 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about multiple myeloma?, http://www.cancer.org/cancer/multiplemyeloma/detailedguide/multiple-myeloma-key-statistics (2016, accessed 1 April 2018).

- 3. Avet-Loiseau H, Fonseca R, Siegel D, et al. Carfilzomib significantly improves the progression-free survival of high-risk patients in multiple myeloma. Blood 2016; 128: 1174–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dimopoulos MA, Oriol A, Nahi H, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1319–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. Elotuzumab therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 754–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. San-Miguel JF, Hungria VT, Yoon SS, et al. Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1195–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. San-Miguel JF, Hungria VT, Yoon SS, et al. Overall survival of patients with relapsed multiple myeloma treated with panobinostat or placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone (the PANORAMA 1 trial): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 2016; 3: e506–e515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siegel DS, Oriol A, Rajnics P, et al. Updated results from ASPIRE and ENDEAVOR, randomized, open-label, multicenter phase 3 studies of carfilzomib in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2017; 17: e142. [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. National comprehensive cancer network: multiple myeloma, http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/myeloma.pdf (2013, accessed 18 August 2018).

- 12. THALOMID®. Prescribing information: Thalomid (thalidomide). Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation, https://media.celgene.com/content/uploads/thalomid-pi.pdf (2017, accessed 14 March 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13. VELCADE®. Prescribing information: Velcade (bortizumib). Cambridge, MA: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc, http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021602s042lbl.pdf (2015, accessed 5 October 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boland E, Eiser C, Ezaydi Y, et al. Living with advanced but stable multiple myeloma: a study of the symptom burden and cumulative effects of disease and intensive (hematopoietic stem cell transplant-based) treatment on health-related quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 46: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Delforge M, Bladé J, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Treatment-related peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma: the challenge continues. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 1086–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohty B, El-Cheikh J, Yakoub-Agha I, et al. Peripheral neuropathy and new treatments for multiple myeloma: background and practical recommendations. Haematologica 2010; 95: 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Cancer Society. Peripheral neuropathy caused by chemotherapy, https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/peripheral-neuropathy.html (2015, accessed 1 April 2018).

- 18. Grisold W, Cavaletti G, Windebank AJ. Peripheral neuropathies from chemotherapeutics and targeted agents: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Neuro Oncol 2012; 14(Suppl. 4): iv45–iv54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trivedi MS, Hershman DL, Crew KD. Management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Am J Hematol Oncol 2015; 11: 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cavaletti G, Cornblath DR, Merkies IS, et al. The chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy outcome measures standardization study: from consensus to the first validity and reliability findings. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 454–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Song X, Cong Z, Wilson K. Real-world treatment patterns, comorbidities, and disease-related complications in patients with multiple myeloma in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 2016; 32: 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index, http://www.bls.gov/cpi/ (2018, accessed 1 June 2018).

- 24. Pike CT, Birnbaum HG, Muehlenbein CE, et al. Healthcare costs and workloss burden of patients with chemotherapy-associated peripheral neuropathy in breast, ovarian, head and neck, and nonsmall cell lung cancer. Chemother Res Pract 2012; 2012: 913848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Calhoun EA, Chang C-H, Welshman EE, et al. Evaluating the total costs of chemotherapy-induced toxicity: results from a pilot study with ovarian cancer patients. Oncologist 2001; 6: 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2014; 155: 2461–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yong K, Delforge M, Driessen C, et al. Multiple myeloma: patient outcomes in real-world practice. Br J Haematol 2016; 175: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martin III TG, Panjabi S, Kerr J, et al. Association of treatment induced peripheral neuropathy (TIPN) with treatment patterns and outcomes in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM). Blood 2013; 122: 1750. [Google Scholar]

- 29. POMALYST®. Prescribing information: Pomalyst (pomalidomide). Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation, http://www.celgene.com/content/uploads/pomalyst-pi.pdf (2018, accessed 18 April 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30. KYPROLIS®. Prescribing information: Kyprolis (carfilzomib). Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc, http://pi.amgen.com/~/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/kyprolis/kyprolis_pi.ashx (2018, accessed 18 April 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31. DARZALEX®. Prescribing information: Darzalex (daratumumab), https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/761036s004lbl.pdf (2016, accessed 18 April 2018).

- 32. EMPLICITI®. Prescribing information: Empliciti (elotuzumab). Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_empliciti.pdf?&utm_source=bing&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=managementbnd&utm_term=prescribinginformation&utm_content=managementbnd_sitelink_pi_empliciti.pdf_text (2017, accessed 18 April 2018). [Google Scholar]