Abstract

Background

The Bariatric Quality of Life Index (BQL) was created and validated as a nine-factor model in 2005 for the measurement of quality of life (QoL)inpatients before and after bariatric surgery. Even though the results were acceptable, the statistical structure of the test was very unclear.

Methods

A total·f466 patients were enrolled in an ongoing prospective longitudinal German study. The assessment took place preoperatively and at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months postoperatively. After that period, reevaluations were done on a yearly basis. In addition to demographic and clinical data, QoL data were collected using the BQL, the Short Form12 (SF-12v2), the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI),and the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS; old version since the study started in 2001). Statistical parameters for contingency (Cronbach's Α),construct and criterion validity (Pearson's r),and responsiveness (standardized effect sizes) were calculated. The data of the assessments conducted preoperatively and after 6 and 12 months were used for the validation.

Results

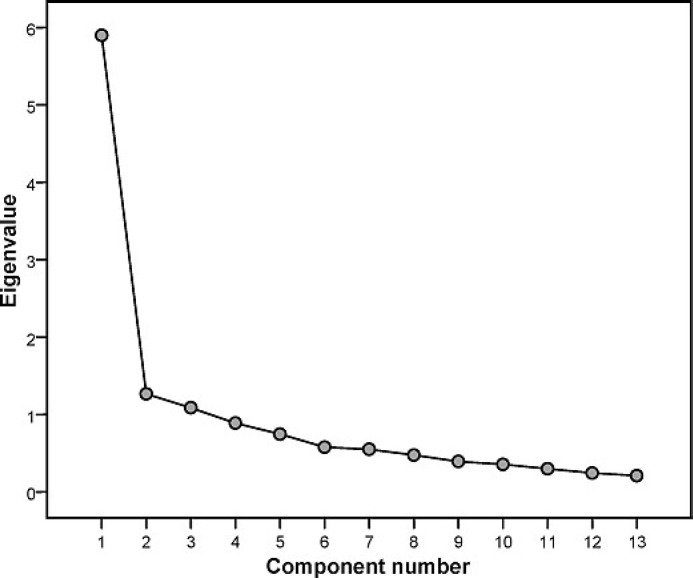

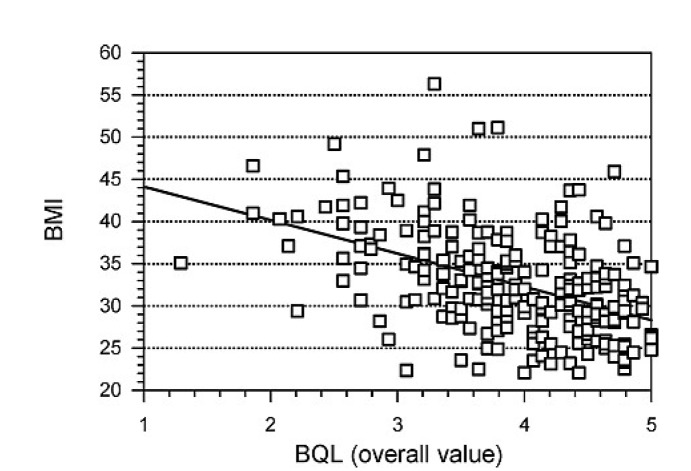

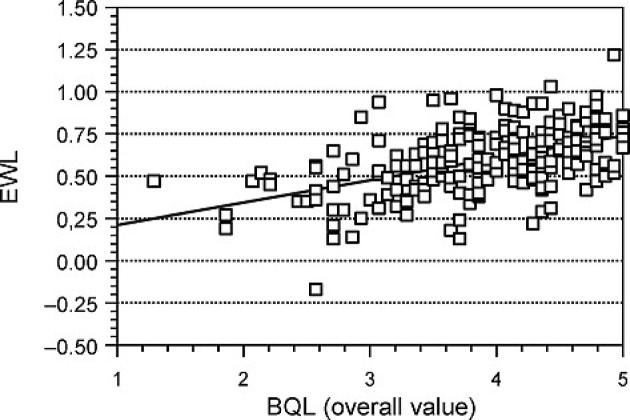

The factor analysis and the screeplot showed that a one-factor solution explained 45.37%of variance. The selectivity of the items ranged between 0.61 and 0.85,and Cronbach's Α was 0.898. The measurements showed similar excellent results with the analysis of all measurement points. Pearson's test showed a good retest reliability (r = 0.9). The correlations with the SF-12 and the Moorehead-Ardelt I questionnaire (MA-I) were significant, while the correlation with the GIQLI was low. The results of the correlation with the excess weight loss (EWL)(0.45 and 0.49) and the BMI (−0.38 and −0.47) were good. Conclusion: The BQL is a valid instrument and should be preferred over generic questionnaires as it provides betterresponsiveness.

Hintergrund

Der Bariatric Quality of Life Index (BQL) wurde 2005 entwickelt und als Neun-Faktoren-Modell zur Erhebung der Lebensqualität bei Patienten nach Adipositaschirurgie validiert. Trotz der akzeptablen Ergebnisse blieb die statische Struktur unklar.

Methoden

466 Patienten wurden im Rahmen einer prospektiven longitudinalen deutschen Studie evaluiert. Die Erhebungen fanden präoperativ und postoperativ nach 1, 3, 6, 9 und 12 Monaten statt. Danach wurden die Untersuchungen jährlich fortgesetzt. Neben der Erfassung demographischer und klinischer Daten wurde die Lebensqualität mit 4 Fragebögen erfasst: dem BQL, dem Short Form 12 (SF-12v2), dem Gastrointestinalen Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) und dem Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS; alte Version genutzt, denn die Studie begann 2001). Als statistische Parameter wurden die interne Konsistenz (Cronbachs a), die Konstrukt- und Kriteriumsvalidität (Pearsons r) und eine Varianzanalyse durchgeführt (standardisierte Effektgrõßen). Für die Validierung wurden die Daten der Erhebungen präoperativ und nach 6 und 12 Monaten verwendet.

Ergebnisse

Die Faktorenanalyse und der Screeplot zeigten, dass eine Ein-Faktor-Lõsung 45,37% der Varianz erklärte. Bei guter interner Konsistenz (Cronbachs a = 0,898) konnten Trennschärfen zwischen 0,61 und 0,85 erreicht werden. Die Berechnungen bei allen anderen Messzeitpunkten ergaben ähnlich gute Ergebnisse. Die Testwiederholungsreliabilität war gut (r = 0,9). Deutlich signifikant waren auch die Korrelationen mit dem SF-12 und dem MA-I-Fragebogen des BAROS, ebenso wie mit dem Excess Weight Loss (EWL) (0,45 und 0,49) und dem BMI (−0,38 und −0,47). Schlussfolgerung: Der BQL ist ein valides Instrument zur Messung der spezifischen Lebensqualität und sollte gegenüber unspezifischen Instrumenten aufgrund seiner hõheren Änderungssensitivität bei der Anwendung bei Patienten nach Adipositaschirurgie bevorzugt werden.

Key Words: Bariatric surgery, Quality of life, Bariatric Quality of Life Index, BQL, Validation

Schlüsselwörter: Bariatrische Chirurgie, Lebensqualität, Bariatric Quality of Life, Index, BQL, Validierung

Introduction

The evaluation of quality of life (QoL) has gained more and more importance not only after bariatric procedures but also after metabolic procedures [1–3]. In 2005, the Bariatric Quality of Life Index (BQL) was created and tested on validity in a single center study [4] following the recommendations of statistical analysis [5] and the needs of bariatric surgeons [6].

The BQL was described as a valid instrument ready for use as a nine-factor model, including medical data on comorbidities, side effects, and medications. As the statistical findings had suggested the need of further investigation, the present study was conducted in order to reevaluate the data with higher numbers of patients. The clear advantages of the BQL are its short and easy design and its easy evaluation which provides a high degree of explanation of variance. Furthermore, it can also be applied before surgery, so that longitudinal comparative studies between different groups of patients and/or different types of surgery can easily be performed [7, 8].

According to the current standards of validation studies [5], we report on contingency, construct and criterion validity, and responsiveness.

Material and Methods

Study Design

The data were collected in an ongoing prospective longitudinal survey executed in a single center in Germany. All patients underwent standardized presurgical evaluation and all procedures were performed laparoscopically. Evaluation took place 1 day prior to surgery, after 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and then at yearly intervals. 3 standardized surgical procedures were evaluated, namely gastric banding, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and BPD-Scopinaro.

Sociodemographic (sex and age) and clinical data (current weight, height, metabolic, pulmonary, cardiovascular, or other comorbidities) were evaluated with the 16-item Non-Quality of Life (NQoL) scale of the BQL. The 16-item scale (NQoL) data and the 14-item scale (QoL) data were treated completely separately.

Questionnaires

For comparative purposes, we administered 4 questionnaires to all patients: the BQL, the Short Form 12 (SF-12v2; short form of the SF-36), the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) and the Bariatric Reporting and Outcome System (BAROS). The old version of the BAROS with the 5-point Likert scale MA-I-QoL questionnaire was used, since the study was started in 2001 and the new version was not available at that time.

The BQL consists of a NQoL subscale, which detects comorbidities, side-effects, and medication intake, and a QoL subscale including 14 items with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0–5 points.

Statistical Validation

Firstly, the structure of the test was assessed by using the factor analysis, following the rules of Kaiser Guttman, and using the screeplot to define the factors and their explanation of the total variance. Cronbach's α was calculated for contingency (or internal consistency). Contingency describes how well the different items of a questionnaire describe the same psychometric construct. For comparison, contingency was also measured for the other questionnaires.

Secondly, we studied the construct validity, which describes the extent to which a measure is related to other similar instruments [9, 10]. This study used Pearson's coefficient r to quantify the correlation between the BQL, the SF-12v2, the GIQLI, and the MA-I (QoL scale of the BAROS). Pearson's r ranges between −1 and 1, and coefficients < 0.6 or 0.8 indicate good or very good correlation, respectively.

Criterion validity was evaluated by analyzing the correlation between the BQL, the BMI, and the excess weight loss (EWL) by using Pearson's r. Criterion validity indicates whether an instrument is correlated to a relevant external outcome variable [9], such as the degree of obesity.

Finally, sensitivity to change (or responsiveness) was studied. Instruments with a high responsiveness are able to detect even small changes over time or small differences between different groups [11]. If this standardized effect size reaches values >0.8 (regardless of plus or minus sign), this indicates good sensitivity to change. In addition, standardized effect sizes were also calculated from the difference between postoperative and preoperative patients divided by the standard deviation of the preoperative patients.

Results

Patients

The sample consisted of 446 patients, who underwent bariatric surgery between 2001 and 2005. All procedures were performed in a single German center according to the rules of the International Federation for Surgery in Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) and the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Although the groups did not show differences regarding age and sex, the BMI was significantly different between the types of surgery (table 1). Mean age was 38.35 years (SD ± 10.02), the mean BMI was 45.15 kg/m2 (SD ± 7.92), and 80.9% of the patients were female. According to the chi-value of 2.61, there was no preference for any type of surgery by the gender of the patients (table 1).

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis was performed regarding the Eigenvalues < 1. With regard to the presurgical data, 4 factors were found (table 2) which showed a strong decrease in the screeplot (fig. 1). Therefore, a one-factor solution had to be chosen, although a four-factor model would have been preferred.

Regarding the results of the factor analysis, the item analysis showed that item 4 had to be removed when calculating on one-factor (table 3). Cronbach's α increased up to 0.898 after removal of item 4.

Contingency

With this item structure, contingency was measured at 3 assessment points: preoperatively, after 6, and after 12 months by calculating Cronbach's α value (table 4).

Sensitivity to Change

Sensitivity to change was measured by calculating the correlations between the results of the BQL at different points in time with the preoperative data. Correlation decreased with time, demonstrating a strong sensitivity to change (table 5).

Construct Validity

The BQL scale correlated well with the SF-12 (r = 0.77–0.81) and the MA-I (r = 0.72–0.77). The correlation of the BQL and the GIQLI was lower than the other correlations (r = 0.32–0.67), which is clear evidence that these 2 questionnaires assess different aspects of QoL (table 6) when considering the fact that all correlations were significant.

Criterion Validity

In the full patient sample, the BQL was correlated positively with the EWL and negatively with the BMI over time (table 7, 8, fig. 2, 3).

Discussion

This study shows that the BQL has to be divided into a NQoL and a QoL scale. The BQL-QoL scale is a valid instrument to assess QoL in morbidly obese patients before or after bariatric surgery. As the results were similarly good as the results of the MA-II validation study [12], the BQL can now be recommended for clinical use. Moreover, our results on contingency (Cronbach's α between 0.898 and 0.93) were better than those of the original validation study, where values between 0.71 and 0.86 were found [4]. In addition to its psychometric characteristics, the BQL is easy and fast to process and provides the surgeon with additional data which enable him to evaluate the current status of the patient quickly.

The results on construct validity clearly demonstrate that the BQL is a disease-specific questionnaire, with even higher contingency (Cronbach's α between 0.898 and 0.93) and construct validity (correlation with the SF-12 between 0.77 and 0.81) than the MA-II (Cronbach's α = 0.84, and correlation with the SF-36 between 0.54 and 069) [12]. Our longitudinal analysis demonstrated the good overall sensitivity to change of the BQL.

From the data on criterion validity it becomes clear that the benefit of bariatric surgery affects the QoL by improving weight.

When comparing the BQL to the generic questionnaire SF-12v2 and the GIQLI, some differences but also similarities emerge. We have shown that even the short form of the SF-36 [13] is a valuable instrument for use in patients after bariatric surgery; although its sensitivity to change and its correlation to disease-specific patterns such as EWL and BMI are lower. Regarding the GIQLI, which was developed for intestinal diseases [14], low correlations could be shown, indicating that the GIQLI is able to assess the impact of bariatric surgery side effects on the QoL, but does not cover the physical and psychological effects of weight loss.

In conclusion, the BQL is a valid instrument to analyze QoL in bariatric patients and is superior to other generic and specific questionnaires. Although it has been tested for validity in all statistical approaches, it still holds opportunities for improvement. It is integrated efficiently into the clinical process when applied to the patient, and it provides an easy way of data collection and measurement.

The BQL questionnaire in its final form can be fully recommended for clinical use. The complete questionnaire including the NQoL scale and the tools for data collection are available for use from the first author of this study. The BQL is available in English and German without license fees.

Fig. 1.

Screeplot.

Fig. 2.

BMI and BQL after 12 months.

Fig. 3.

BQL and EWL after 12 months.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and type of surgery

| Gastric Banding |

Gastric Bypass |

BPD-Scopinaro | Total | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 94 | 293 | 59 | 44 | – |

| Female | 80 | 237 | 44 | 361 | |

| Male | 14 | 56 | 15 | 85 | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 38.6 ± 11.6 | 38.27 ± 9.5 | 38.32 ± 9.84 | 38.35 ± 10.0 | 0.16 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 44.57 ± 8.06 | 48.3 ± 7.5 | 51.06 ± 8.25 | 44.15 ± 7.92 | < 0.001 |

Table 2.

Factor analysis

| Factor | Eigenvalue | Variance, % | Total variance, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.99 | 42.8 | 42.8 |

| 2 | 1.29 | 9.2 | 52.0 |

| 3 | 1.16 | 8.3 | 60.3 |

| 4 | 1.01 | 7.2 | 67.5 |

Table 3.

Item analysis

| Variable | Factor 1 |

|---|---|

| BQ_0_1 | 0.45194 |

| BQ_0_2 | 0.41637 |

| BQ_0_3 | 0.68278 |

| BQ_0_4 | 0.35028 |

| BQ_0_5 | 0.67742 |

| BQ_0_6 | 0.71868 |

| BQ_0_7 | 0.71241 |

| BQ_0_8 | 0.67829 |

| BQ_0_9 | 0.60970 |

| BQ_0_10 | 0.74777 |

| BQ_0_11a | 0.72547 |

| BQ_0_11b | 0.73566 |

| BQ_0_11c | 0.75996 |

| BQ_0_12 | 0.71332 |

Table 4.

Contigency of the BQL at different points in time

| Eigenvalue | Communality | Cronbach's α | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t0 | 5.89 | 45.3 | 0.89 | 159 |

| t6 | 6.65 | 51.2 | 0.92 | 287 |

| t12 | 7.29 | 56.1 | 0.93 | 231 |

t0: Before surgery; t6, t12: 6, 12 months after surgery, respectively.

Table 5.

Sensitivity to change of the BQL (Pearson's r)

| BQL (t1) | BQL (t6) | BQL (t12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BQL (t0) | 0.62 | 0.479 | 0.3036 |

| p | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.01 |

t0: Before surgery; t1, t6, t12: 1, 6, 12 months after surgery, respectively.

Table 6.

Construct validity of the BQL for different assessment points

| SF-12 | GIQLI | (MA-I)BAROS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BQL (t0) | 0.77** | 0.32** | 0.76** |

| BQL (t6) | 0.77** | 0.61** | 0.77** |

| BQL (t12) | 0.81** | 0.67** | 0.72** |

t0: Before surgery; t6, t12: 6, 12 months after surgery, respectively.

p < 0.01.

Table 7.

Correlation between BQL and BMI

| BMI (t0) | BMI (t6) | BMI (t12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BQL (t0) | –0.12 | –0.13 | –0.0 |

| BQL (t6) | –0.11 | –0.38 | –0.37 |

| BQL (t12) | –0.06 | –0.36 | –0.4 |

t0: Before surgery; t6, t12: 6, 12 months after surgery, respectively.

Table 8.

Correlation BQL and EWL in %

| EWL (t0) | EWL (t6) | EWL (t12) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BQL (t0) | 0.00 | 0.11 | –0.8 |

| BQL (t6) | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.31 |

| BQL (t12) | 0.14 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

t0: Before surgery; t6, t12: 6, 12 months after surgery, respectively.

References

- 1.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Assessing weight-related quality of life in obese persons with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR, Hartley GG, Nicol S. The relationship between health-related quality of life and weight loss. Obes Res. 2001;9:564–571. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner S, Sauerland S, Fein M, Blanco R, Pomhoff I, Weiner RA. The Bariatric Quality of Life (BQL) index: a measure of well-being in obesity surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:538–545. doi: 10.1381/0960892053723439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauerland S, Angrisani L, Belachew M, Chevallier JM, Favretti F, Finer N, Fingerhut A, Garcia Caballero M, Guisado Macias JA, Mittermair R, Morino M, Msika S, Rubino F, Tacchino R, Weiner R, Neugebauer EA, Obesity surgery. evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) Surg Endosc. 2005;19:200–221. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner S, Sauerland S, Weiner R, Pomhoff I. Quality of life after bariatric surgery - is there a difference? Chir Gastroenterol. 2005;21:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiner S, Sauerland S, Weiner RA, Rosenthal A, Pomhoff I. Lebensqualität nach Adipositaschirurgie: Ergebnisse nach verschiedenen Operationsverfahren - erste Ergebnisse einer prospektiven Längsschnittstudie. Chir Gastroenterol. 2007;23((suppl 1)):52–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DA, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terwee CB, Dekker E, Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Bossuyt P. On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: guidelines for instrument evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:349–362. doi: 10.1023/a:1023499322593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Methods for assessing responsiveness: a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorehead MK, Ardelt-Gattinger E, Lechner H, Oria HE. The validation of the Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life Questionnaire II. Obes Surg. 2003;13:684–692. doi: 10.1381/096089203322509237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD, The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eypasch E, Wood-Dauphinée S, Williams JI, Ure B, Neugebauer E, Troidl H, Der Gastrointestinale Lebensqualitätsindex (GLQI) Ein klinimetrischer Index zur Befindlichkeitsmessung in der gastroenterologischen Chirurgie. Chirurg. 1993;64:264–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]