Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health problem associated with an eight- to ten-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality. Among patients with CKD, on drug treatment, we aimed to determine the characteristics, etiology, patterns and rates of drug use, and outcomes and factors determining the outcomes at 6 months.

METHODS:

We conducted an observational follow-up study on inpatients with CKD at a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. We collected data on patient characteristics, comorbidities, treatments at baseline, and treatments and outcomes at 6 months. We used Chi-squared tests and Cochran's Q-test to compare categorical variables, t-tests to compare continuous variables, and a multivariable logistic regression analysis to estimate the determinants of the outcome.

RESULTS:

We recruited 305 patients with the mean age 52.98 (±14.89) years, 73.1% were male and 55.4% patients were from a lower-middle socioeconomic background. About 72.1% were in CKD Stage 5 and 37.0% had diabetic nephropathy. Antihypertensives (84.6%) were the most common drug class prescribed, followed by multivitamins (65.2%), proton-pump inhibitors (64.9%), and antidiabetic drugs (32.5%). There was no significant difference in rates of drug use over 6 months. Increased serum creatinine (odds ratio [OR]: 1.29 [1.04, 1.60]; P = 0.017) and lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (OR: 38.23 [3.92, 372.06]; P = 0.002) predicted progression of CKD, and antiplatelets reduced progression (OR: 0.278 [0.09, 0.85]; P = 0.026).

CONCLUSION:

Diabetic nephropathy was the most common cause of CKD. There was no change in treatments over 6 months. Low eGFR predicted progression and use of antiplatelets reduced progression of CKD. Large multicenter studies are needed to study the variability in patient characteristics, treatment and outcomes to obtain a national picture, and to enable policy changes.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, demography, etiology, India, outcomes, pharmacotherapy

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major global public health problem and is a key determinant of poor outcomes of major noncommunicable diseases. CKD is associated with an eight- to ten-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality and is a risk multiplier in patients with diabetes and hypertension.[1]

In the meta-analysis in 2016 by Hill et al., the estimated global prevalence among all the stages of CKD varied between 10% and 13%, and in India, varied between 6% and 13%.[2] Low- and middle-income countries have the greatest burden of CKD, accounting for 80% of all cases of CKD globally.[3] Data on CKD in developing countries are scanty, invalidated, and heterogeneous, making comparisons difficult. In the SEEK-India, the prevalence was 17.2% and was higher in males (>60%).[4]

CKD can be a manifestation of other chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension. Previous studies from India used a cross-sectional design and obtained data from only advance stages of CKD (Stage 3, Stage 4, and Stage 5) and had nonuniform cutoff values to define kidney disease. There are no studies in India on the treatment and short-term outcomes in CKD.

Our objectives were, among CKD patients admitted to a tertiary care hospital, to assess the etiology, patient characteristics, pattern and rates of drug use, and outcomes and factors determining outcomes at 6 months.

Methods

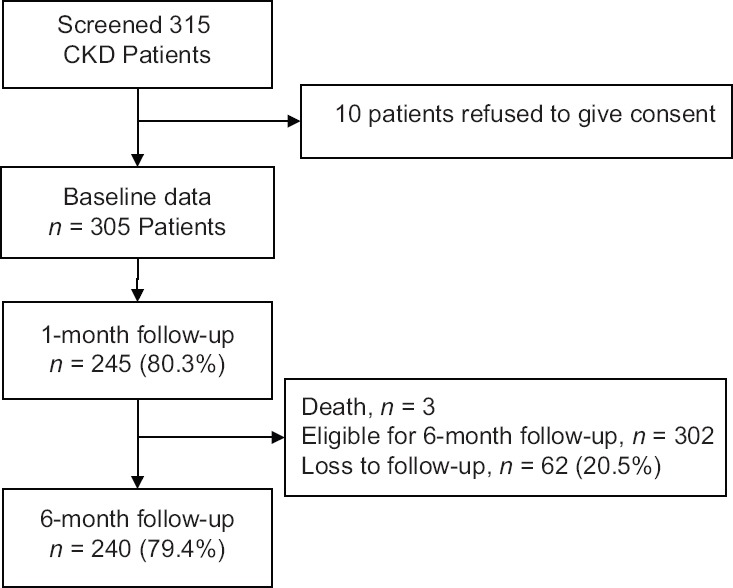

We conducted a prospective, observational 6-month follow-up study at St. John's Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru, over 17 months. This is a tertiary care teaching hospital with a large dialysis program. Recruitment was done from January to November 2013. Patients were followed up at 1–3 months and at 6 months [Figure 1]. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC Ref. No: 112/2014). The study was explained in the language understood by the patient and informed consent was obtained. We included patients with CKD Stages 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 and aged ≥18 years irrespective of whether they were on dialysis. The CKD stage was classified according to the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative 2002 guidelines into five stages.[5] We excluded patients in whom the 6-month follow-up was not possible and those with acute on CKD.

Figure 1.

Patient recruitment and follow-up

At baseline, we collected the patient characteristics, laboratory and treatment data. At 1–3 and 6 months, we collected the data on treatments, laboratory parameters, and outcomes. Based on the patient education, occupation, monthly income, objects/materials owned, and number of dependents socioeconomic status was classified as rich, upper middle, lower middle, and poor.

The outcomes were progression of CKD, progression to dialysis, and change in the frequency of dialysis, death, cardiovascular outcomes (angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke), neurological outcomes (seizures and coma), and hospitalization due to any cause. For sample size estimation, we assumed 20% of cardiovascular events and hospitalization due to all causes in CKD patients in Stage 2, 3, 4, and 5 at 6 months.[6] For a 5% absolute precision and 95% confidence interval (CI), the sample size needed is 246. With an expected dropout rate of 20%, the sample size required is 296 patients.

We summarized baseline data as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (interquartile range) and used Cochran's Q-test for significance between proportions of patients persistent to drug treatments at 1–3 months and at 6 months. To assess the determinants of progression of CKD, we undertook a multivariable logistic regression analysis. Progression of CKD at 6 months was the dependent variable, and the independent variables were patient characteristics (age, sex, socioeconomic status, and education levels), risk factors (serum creatinine, urea, sodium, potassium, and serum calcium), treatment patterns (use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs], angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], beta-blockers, phosphate binders, calcium channel blockers, antiplatelet agents, calcium supplements, and erythropoietin), and associated complications (anemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia). We report the adjusted odds ratio (OR) with their 95% CIs. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. Statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

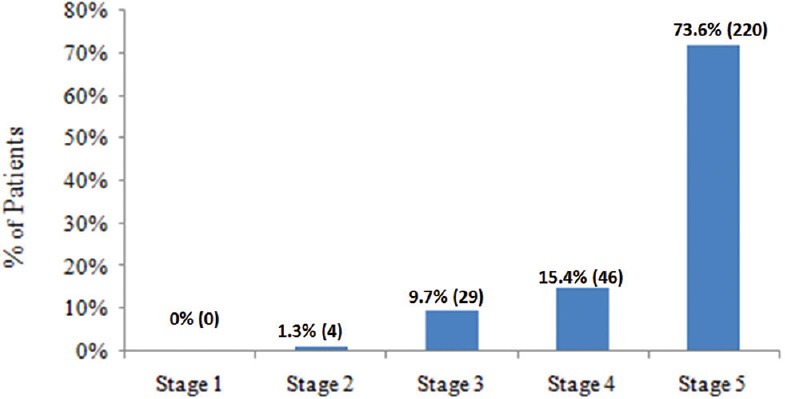

The mean age (±SD) was 52.98 (±14.89) years. Hypertension was the most common comorbid condition (283 [92.8%]), followed by diabetes mellitus (166 [54.4%]) and ischemic heart disease (27 [8.9%]) Table 1. The median duration of CKD was 31.50 (12.00, 60.00) months. CKD stage was available for 299 (98.0%) patients [Figure 2]. Of the 305 patients, cause of CKD was available in 226 (74.09%) patients. The most common cause for the development of CKD was diabetic nephropathy (113, 37.0%), followed by chronic interstitial nephritis (34, 11.1%), chronic glomerular nephritis (26, 8.5%), and hypertensive nephropathy (15, 4.9%). Serum creatinine was available for 299 (98.0%) patients and the mean level was 6.79 ± 3.50 mg/dl. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula in 298 (97.7%) patients and the mean was 13.36 ± 11.32. At recruitment, 202 (66.2%) patients were currently on dialysis. Of these, 198 (98.0%) were on hemodialysis (HD) and 4 (2.0%) were on peritoneal dialysis Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with chronic kidney disease (n=305)

| Baseline characteristics | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Age, (mean±SD) | 52.98±14.89 |

| Male, n (%) | 223 (73.1) |

| Place of residence, n (%) | |

| Rural | 87 (28.7) |

| Semi - Urban | 11 (3.6) |

| Urban | 205 (67.6) |

| Educational status, n (%) | |

| None | 38 (12.5) |

| School | 58 (19.0) |

| High school | 114 (37.4) |

| Degree | 93 (30.5) |

| Professional | 2 (0.7) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed | 82 (26.9) |

| Unemployed | 74 (24.3) |

| Retired | 77 (25.2) |

| Home maker | 57 (18.7) |

| Self-employed | 12 (3.9) |

| Student | 3 (1.0) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | |

| Rich | 7 (2.3) |

| Upper middle | 128 (42.0) |

| Lower middle | 169 (55.4) |

| Poor | 1 (0.3) |

| Co-morbid conditions, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 283 (92.8) |

| Diabetes | 166 (54.4) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 27 (8.85) |

| Heart failure | 7 (2.3) |

| Stroke | 1 (0.3) |

| Duration of CKD in months, median (IQR) | 31.50 (12.00-60.00) |

| Family history of CKD or kidney disorders, n (%) | 30 (9.8) |

| Cause of CKD, n (%) | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 113 (37.0) |

| Chronic interstitial nephritis | 34 (11.1) |

| Chronic glomerular nephritis | 26 (8.5) |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 15 (4.9) |

| Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | 9 (3.0) |

| IgA nephropathy | 8 (2.6) |

| Obstructive uropathy | 4 (1.3) |

| Cause not available | 79 (25.9) |

| Patients presently on dialysis | 202 (66.2) |

| Haemodialysis | 198 (98.0) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 4 (2.0) |

| Past history of dialysis | 20 (6.6) |

| Renal transplant done, n (%) | 5 (1.6) |

CKD: Chronic kidney disease, SD: Standard deviation, IQR: Interquartile range

Figure 2.

Stages of chronic kidney disease

Drugs prescribed to CKD patients were assessed at baseline (n = 305), 1–3 months (n = 245), and at 6 (n = 240) months. Among drugs, antihypertensives (84.6%) were the most commonly prescribed, followed by multivitamins (65.2%) and proton-pump inhibitors (64.9%), at baseline. There was a significant increase in the prescription of Vitamin D analogs and calcium supplements at 3 months from baseline (42.3% vs. 51.4%; P = 0.003) Table 2.

Table 2.

Drugs prescribed for patients over 6 months

| Drug class | Baseline, n (%) (n=305) | 1-3 months, n (%) (n=245) | 6 months, n (%) (n=240) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-hypertensive | 258 (84.6) | 215 (87.7) | 203 (84.5) | 0.301 |

| ACE inhibitors | 15 (4.9) | 12 (4.8) | 12 (5.0) | 0.180 |

| ARBs | 19 (6.2) | 16 (6.5) | 19 (7.9) | 0.459 |

| Alpha blockers | 99 (32.5) | 77 (31.4) | 76 (31.6) | 0.453 |

| Alpha + beta blockers | 38 (12.5) | 33 (13.4) | 31 (12.9) | 0.249 |

| Beta blockers | 114 (37.4) | 96 (39.1) | 94 (39.1) | 0.971 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 218 (71.5) | 171 (69.7) | 159 (66.2) | 0.393 |

| Centrally acting agents | 116 (38.0) | 100 (40.8) | 98 (40.8) | 0.679 |

| Vasodilators | 23 (7.5) | 17 (6.9) | 18 (7.5) | 0.895 |

| Isosorbide dinitrate + hydralazine | 38 (12.5) | 36 (14.6) | 32 (13.3) | 0.291 |

| Anti-diabetics | 99 (32.5) | 73 (29.7) | 80 (33.3) | 0.538 |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 10 (3.2) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (2.91) | 0.135 |

| Insulins | 81 (26.6) | 58 (23.6) | 54 (22.5) | 0.152 |

| Diuretics | 31 (10.2) | 31 (12.6) | 25 (10.4) | 0.779 |

| Anti anginal | 24 (7.9) | 13 (5.30) | 14 (5.8) | 0.122 |

| Anti-platelet agents | 103 (33.8) | 91 (37.1) | 84 (35.0) | 0.505 |

| Hypolipidemic agents | 80 (26.2) | 66 (26.9) | 63 (26.2) | 0.966 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 198 (64.9) | 156 (63.6) | 146 (60.8) | 0.601 |

| Calcium and vitamin D analogues | 129 (42.3) | 126 (51.4) | 98 (40.8) | 0.003 |

| Phosphate binders | 61 (20.0) | 61 (24.8) | 56 (23.3) | 0.404 |

| Erythropoietin | 158 (51.8) | 128 (52.2) | 121 (50.4) | 0.732 |

| Multivitamins | 199 (65.2) | 167 (68.1) | 153 (63.7) | 0.654 |

*Cochran’s Q was used to test for significance between proportion of patients taking drug treatments at different time points, P≤0.05 is considered statistically significant. ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, ARBs: Angiotensin receptor blockers

Follow-up at 6 months was available for 240 patients (79%). Sixty-two patients were lost to follow-up due to migration, change in hospital, of which 71% patients were from lower and poor socioeconomic strata. The rate of death was highest in Stage 5 CKD (7.3%) patients as compared to other stages. Hospitalization and initiation of dialysis were more frequent in patients with eGFR ≤15 compared to patients with eGFR >15 (26.8% vs. 15.4%, [P = 0.042]; 4.5% vs. 1.3%, [P = 0.0001], respectively). Fourteen (17.9%) patients with eGFR >15 progressed to a higher CKD stage. Hyperkalemia (36.8% vs. 14.1% [P = 0.0001], hypocalcemia [25.5% vs. 7.7% (P < 0.0001)], and hyperphosphatemia [27.3% vs. 6.4% [P < 0.0001]), raised blood urea (41.4% vs. 15.4% [P < 0.0001]), and anemia (67.7% vs. 38.5% [P < 0.0001]) were more prevalent in patients with eGFR ≤15 Table 3.

Table 3.

Outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients at 6 months by estimated glomerular function rate levels and socioeconomic status*

| Events | Group based on eGFR | P# | Groups based on socioeconomic status | P# | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR >15 mL/min/1.73m2 (Stage 2, 3 and 4) n=79, n (%) | eGFR ≤15 mL/min/1.73m2 (Stage 5) (n=220), n (%) | Rich and upper middle class (n=135), n (%) | Lower middle class and poor (n=170), n (%) | |||

| Death | 2 (2.6) | 16 (7.3) | 0.172 | 8 (5.9) | 10 (5.9) | 0.987 |

| Cardiovascular events | 5 (6.4) | 9 (4.1) | 0.533 | 6 (4.4) | 9 (5.3) | 0.733 |

| Hospitalization | 12 (15.4) | 59 (26.8) | 0.042 | 41 (30.4) | 33 (19.4) | 0.027 |

| Progression of CKD stage | 14 (17.9) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 | 9 (6.7) | 5 (2.9) | 0.001 |

| Initiation of dialysis | 1 (1.3) | 10 (4.5) | <0.0001 | 7 (5.2) | 4 (2.4) | 0.008 |

| Progression in the frequency of dialysis from 2 to 3 times/week | 0 (0.0) | 13 (5.9) | <0.0001 | 7 (5.2) | 6 (3.5) | 0.008 |

| Underwent renal transplantation | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.8) | 0.576 | 4 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.037 |

| Shifted from haemodialysis to peritoneal dialysis | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.8) | 0.576 | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 1.000 |

| Remission to previous CKD stage | 4 (5.1) | 6 (2.7) | 0.295 | 6 (4.4) | 4 (2.4) | 0.347 |

| Hyperkalemia | 11 (14.1) | 81 (36.8) | 0.001 | 47 (34.8) | 46 (27.1) | 0.011 |

| Hypocalcemia | 6 (7.7) | 56 (25.5) | <0.0001 | 35 (25.9) | 28 (16.5) | 0.018 |

| Hyperphosphatemia | 5 (6.4) | 60 (27.3) | <0.0001 | 31 (23.0) | 35 (20.6) | 0.041 |

| Raised blood urea | 12 (15.4) | 91 (41.4) | <0.0001 | 51 (37.8) | 54 (31.8) | 0.027 |

| Anaemia | 30 (38.5) | 149 (67.7) | <0.0001 | 92 (68.1) | 88 (51.8) | 0.002 |

*Compared using Chi squared test, for cells with expected count <5, Fisher’s exact test was considered, #P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. eGFR: Estimated glomerular function rate, CKD: Chronic kidney disease

Rates of death were similar in the rich, upper-middle class (UMC), and lower-middle class (LMC) (4.4% vs. 7.9%, P = 0.256). About 35.1% of patients in the rich and UMC groups were hospitalized for over 6 months. Proportion of patients progressing to higher CKD stages, initiation of dialysis and progression in the frequency of dialysis were higher in the rich and UMC group (7.9% vs. 4.0% [P = 0.002], 6.1% vs. 3.2% [P = 0.009], and 6.1% vs. 4.8% [P = 0.033]) compared to LMC and poor. Only the rich and UMC patients underwent renal transplantation 4 (3%) Table 3.

To perform univariate analysis, based on the previous studies, we selected the following independent variables: age, male gender, low socioeconomic status, unemployment, illiteracy, family history of kidney disease, duration of CKD, serum creatinine blood urea, eGFR, electrolytes, phosphorous, calcium, use of drugs, anemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, and raised blood urea. In our study, duration of CKD, serum creatinine, eGFR, antiplatelet agents, phosphate binders, hyperkalemia, and raised blood urea were significant predictors for progression of CKD. These variables were included in the multiple logistic regression model. This model showed that patients with higher serum creatinine levels (adjusted OR and 95% CI, 1.296, [1.04, 1.60]; P = 0.017) and eGFR ≤15 (OR, 95% CI, 38.23, (3.92, 372.06); P = 0.002) are more likely to progress to higher CKD stages. We also noted that use of antiplatelet agents reduced progression (0.278, [0.09, 0.85]; P = 0.026) Table 4.

Table 4.

Factors determining the progression of chronic kidney disease

| Variables | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| Duration of CKD | 0.989 | 0.974 | 1.004 | 0.163 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.296 | 1.047 | 1.606 | 0.017 |

| eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73m2 | 38.231 | 3.928 | 372.065 | 0.002 |

| Use of Antiplatelet agents | 0.278 | 0.090 | 0.857 | 0.026 |

| Use of Phosphate Binders | 4.008 | 0.824 | 19.494 | 0.085 |

| Hyperkalemia | 2.369 | 0.652 | 8.616 | 0.190 |

| Raised blood urea | 13.874 | 0.932 | 206.454 | 0.056 |

CI: Confidence interval, OR: Odds ratio, eGFR: Estimated glomerular function rate, CKD: Chronic kidney disease

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first follow-up study of CKD in India. In our study, diabetic nephropathy (50.2%) was the major cause of CKD. Raised serum creatinine and eGFR < 15 increased the progression of CKD. There was no change in the treatment pattern over 6 months. The mean age of the patients in our study was 52.98 (±14.89) years with 73.1% males and median CKD duration of 31.50 months (interquartile range, 12.0–60.0). This was comparable to the mean age and gender proportion of the first cross-sectional Indian CKD study.[7] This study included cross-sectional data on 52,273 CKD patients with the mean age of 50.1 years and 70.3% males. The Spanish EPIRCE study on 237 patients reported the mean age of 49.58 years, which was comparable to our study but with lower proportion of males (42.6%).[8]

In our study, 67.6% of the patients resided in urban areas and 68.52% patients had education equivalent to high school or higher. These proportions were comparable to the SEEK-India study,[4] which included 5588 CKD patients in India.

In our study, majority of the patients (72.1%) were in CKD Stage 5. In the Indian CKD registry and the SEEK-India study, the proportion of patients in CKD stage 5 is 48.1% and 0.8%, respectively. This is because our study was conducted at a tertiary care referral hospital.

Most patients in our study had hypertension (92.8%) and over half had diabetes (54.4%). Similar rates were seen in the SEEK-India study. The Spanish EPIRCE study had lower rates of hypertension (31.5%) and diabetes (8%).

In our study, diabetic nephropathy (50.2%) was the major cause of CKD, similar to the Indian CKD registry (31.3%).[7] We recorded that antihypertensives were the most commonly prescribed (84.6%) drugs. There was relatively lower use of ACEIs and ARBs in our study due to the inclusion of higher proportion of CKD Stage 5 patients. In the Malaysia study,[9] mineral supplements were the major drug class (79.1%), followed by multivitamins in 74.5% and anti-anemic preparations in 70.5% of patients. In a study among CKD patients on maintenance HD by Chakraborty et al., cardiovascular drugs (23.4%) were commonly used, followed by gastrointestinal drugs (15.76%) and vitamins (12.29%).[10] In a study by Mustafar et al., there was a significant reduction in the serum calcium followed by return to its baseline values at later stages. This pattern would have probably led on to an increase in the prescription of calcium and Vitamin D at 3 months in our study.[11] There are no follow-up studies in India comparing changes in the treatment.

At 6 months, 18 (5.9%) patients died and 22 (7.2%) progressed to a higher CKD. A study in the US on 1.1 million patients followed up for 2.84 years reported 4.5% deaths, 12.3% cardiovascular events, and 49.5% hospitalization due to any cause.[6] In our study, lower eGFR (<15 mL/min/1.73 m2) was associated with increased risk of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization which was similar to the findings in the SAVE study where there was an 81% increased risk of mortality with eGFR <45 ml/min when compared with eGFR >75 ml/min (risk ratio [RR] = 1.81 [1.32, 2.48], P = 0.001).[12]

We demonstrated that increased serum creatinine and lower eGFR are significant predictors of progression of CKD. In a study by mild and moderate kidney disease study group, the serum creatinine was a significant predictor of progression of CKD (r = −0.848; P < 0.001).[13] We also noted that, the use of antiplatelet agents reduced the progression of CKD and the mechanism is unknown. A meta-analysis by Palmer et al. showed that antiplatelet therapy among CKD patients, reduced the risk of myocardial infarction by 13% (RR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.76, 0.99), and on the contrary, increased the risk of major (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.10, 1.65) and minor (RR 1.49, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.97) bleeding.[14]

Our study has some limitations. This is a single-center tertiary care hospital. Fifteen (4.6%) patients refused to participate and 62 (20.3%) were lost to follow-up at 6 months. This likely underestimated the rates of outcomes. The short follow-up period of 6 months did not enable us to understand the longer term determinants of the clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

In this first follow-up study of CKD in India, we determined that diabetic nephropathy was the most common cause of CKD. There was no change in the treatment over 6 months indicating good care by the hospital. Serum creatinine, lower eGFR, and use of antiplatelets affected the progression of CKD. To better understand the causes of CKD and its determinants in India, a multicenter study with large numbers and longer follow-up is needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Couser WG, Remuzzi G, Mendis S, Tonelli M. The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1258–70. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, Hirst JA, O'Callaghan CA, Lasserson DS, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease – A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanifer JW, Muiru A, Jafar TH, Patel UD. Chronic kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:868–74. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh AK, Farag YM, Mittal BV, Subramanian KK, Reddy SR, Acharya VN, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of chronic kidney disease in India – Results from the SEEK (Screening and early evaluation of kidney disease) study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajapurkar MM, John GT, Kirpalani AL, Abraham G, Agarwal SK, Almeida AF, et al. What do we know about chronic kidney disease in India:First report of the Indian CKD registry. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EPIRCE Study Group. Otero A, Gayoso P, Garcia F, de Francisco AL. Epidemiology of chronic renal disease in the Galician population: Results of the pilot spanish EPIRCE study. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;68:S16–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Ramahi R. Medication prescribing patterns among chronic kidney disease patients in a hospital in Malaysia. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakraborty S, Ghosh S, Banerjea A, De RR, Hazra A, Mandal SK, et al. Prescribing patterns of medicines in chronic kidney disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Indian J Pharmacol. 2016;48:586–90. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.190760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mustafar R, Mohd R, Ahmad Miswan N, Cader R, Gafor HA, Mohamad M, et al. The effect of calcium with or without calcitriol supplementation on renal function in patients with hypovitaminosis D and chronic kidney disease. Nephrourol Mon. 2014;6:e13381. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tokmakova MP, Skali H, Kenchaiah S, Braunwald E, Rouleau JL, Packer M, et al. Chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular risk, and response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition after myocardial infarction: The survival and ventricular enlargement (SAVE) study. Circulation. 2004;110:3667–73. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149806.01354.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spanaus KS, Kollerits B, Ritz E, Hersberger M, Kronenberg F, von Eckardstein A, et al. Serum creatinine, cystatin C, and beta-trace protein in diagnostic staging and predicting progression of primary nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Clin Chem. 2010;56:740–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.138826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer SC, Di Micco L, Razavian M, Craig JC, Perkovic V, Pellegrini F, et al. Antiplatelet agents for chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD008834. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008834.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]