Abstract

A series of five randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) conducted between 2002 and 2015 support the potential efficacy of online family problem-solving treatment (OFPST) in improving both child and parent/family outcomes after pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, small sample sizes and heterogeneity across individual studies have precluded examination of potentially important moderators. We jointly analyzed individual participant data (IPD) from these five RCTs, involving 359 children and adolescents between the ages of 5 and 18 years, to confirm the role of previously identified moderators (child's age and pre-treatment symptom levels, parental education) and to examine other potential moderators (race, sex, IQ), using IPD meta-analysis. This reanalysis revealed statistically strong evidence that parental education, child age at baseline, IQ, sex, and parental depression level pre-treatment moderated the effect of OFPST on various outcomes. In particular, children of parents with a less than high school education exhibited fewer internalizing problems and better social competence. Children injured at an older age exhibited fewer externalizing behaviors and less executive dysfunction following OFPST. Child IQ moderated the effect of OFPST on social competence, with significantly better competence for children with lower IQ who received OFPST. Lower levels of parental depression followed OFPST among subgroups with lower IQ, boys, and higher parental depression scores at baseline. Our findings indicate that the optimal application of OFPST is likely to involve older children, those with lower IQ scores, or those from families with lower socioeconomic status (SES).

Keywords: brain injury, heterogeneous treatment effects meta-analysis, precision medicine

Introduction

Pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with a broad range of adverse behavioral consequences, including executive dysfunction, behavioral dysregulation, anxiety/post-traumatic stress, and depression.1–5 Novel psychiatric diagnoses likewise often follow pediatric TBI, with secondary attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (SADHD) occurring most commonly and affecting as many as 20% of children.3,6,7 Pediatric TBI also profoundly affects parents and families, with as many as 50% of parents reporting elevated levels of depression or distress.8 Parents also report elevated family burden and deterioration in family functioning that may persist for years following the injury.9

Given the heterogeneity of outcomes following pediatric TBI and the challenges of conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in this population, few evidence-based treatments exist. However, a series of five RCTs conducted between 2002 and 2015 provide support for the potential efficacy of online family problem-solving treatment (OFPST) in improving both child and parent/family outcomes.10–17 Across these studies, treatment efficacy was moderated by injury severity, child characteristics such as age or pre-treatment functioning, and family demographic characteristics such as parental marital status, education, and income.10–13,15–17 Although older children and adolescents receiving OFPST consistently demonstrated a greater reduction in behavior problems at follow-up than younger children, associations of family characteristics with both parent and child treatment outcomes were more complex. Among families with lower, but not higher, socioeconomic status (SES), as defined by parental education or income, OFPST was associated with greater improvements than the Internet resource comparison (IRC) treatment;10,17,18 in contrast, unmarried parents in the OFPST group reported less improvement in child behavior than married parents.19 Drawing definitive conclusions from these complicated results was hampered by small and heterogeneous samples, which also precluded exploration of potentially important moderation by variables such as the child's race, sex, and cognitive functioning/IQ.

These same RCT design limitations have generally made it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of behavioral interventions for pediatric TBI. The International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI (IMPACT) has provided an example of how to use individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis to leverage data from multiple prognostic studies to obtain a more powerful analysis. In fact, IPD meta-analysis has been recognized as having many advantages over traditional meta-analysis based on summary data from publications, and has been widely used in examining the effects of treatment for cardiovascular disease, cancer, Alzheimer's disease, dyspepsia, epilepsy, malaria, and HIV infection.20 In contrast to competing methods, IPD meta-analysis provides patient-centric results21 and naturally capitalizes on any patient heterogeneity across studies, but has not yet been widely adopted to synthesize RCT data in TBI research.

We employed IPD meta-analysis to confirm the role of previously identified moderators (injury severity, child's age and pre-treatment symptom levels, parental education) and to examine other potential moderators, such as race, sex, IQ, and pre-morbid learning and attention problems that were not previously considered because of limitations in sample size and statistical power. We hypothesized that older children and those of lower SES receiving OFPST would demonstrate significantly greater improvements in child behavioral outcomes at follow-up, including fewer internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, less executive dysfunction, and greater social competence. Similarly, we hypothesized that parental education, our proxy for SES, and pre-treatment levels of parental symptoms would moderate improvements in parental depression and distress, with significantly greater improvements in parent outcomes among less educated parents and those with more initial symptoms. Given the additional power afforded by the IPD approach, we conducted exploratory analyses examining the role of injury severity, race, sex, and IQ as moderators of the treatment effects.

Methods

Overview

We jointly analyzed IPD of 359 children and adolescents 5–18 years of age collected across five RCTs of OFPST for pediatric TBI. One of the authors was principal investigator (PI) for each study, all of which have been conducted since 2000 and randomized participants to OFPST or one or more alternative treatments (Table 1). Because substantial deviations in therapist training at one site in one study raised questions of treatment fidelity, we excluded the IPD for all seven subjects recruited at that site.

Table 1.

Recruitment Summary by Study

| Characteristic | Online | CDC | TOPS-Orig | CAPS | TOPS-RRTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full study name | Online Problem Solving | Group versus Individual Problem Solving | Teen Online Problem Solving | Counselor Assisted Problem Solving | Teen Online Problem Solving Multisite Study |

| na | 43 | 85 | 40 | 132 | 152 |

| Datesb | 2003–4 | 2005–6 | 2006–9 | 2007–11 | 2010–14 |

| Typical procedurec | Recruitment from a trauma registry or during inpatient hospitalization/rehabilitation, with potential participants contacted by letter with follow-up by phone or in person at a clinic | ||||

| Procedure anomaliesd | No inpatient recruitment | Additional recruitment at neurosurgery follow-up clinic, but no inpatient recruitment | No inpatient recruitment | ||

| Age (y) | 5–18 | 5–18 | 11–18 | 12–17 | 11–18 |

| Time since injury (m) | 0–24 | 0–24 | 0–24 | 0–7 | 0–18 |

| Injury severityc,e | Overnight hospitalization, GCS score <13 or 13-15 with positive neuroimaging findings | ||||

| Typical exclusionary criteriac | Abusive head trauma, insufficient recovery for child to participate, significant pre-injury intellectual impairment, pre-injury psychiatric hospitalizations, parent hospitalized for psychiatric reasons in past year | ||||

| Exclusionary criteria reductionsf | Pre-injury intellectual impairment, pre-injury psychiatric hospitalizations, and parent hospitalization for psychiatric reasons | Pre-injury psychiatric hospitalizations, and parent hospitalization for psychiatric reasons | |||

| Treatment groups | OFPS, IRC | OFPS, OMFG, UC | OFPS, IRC | OFPS, IRC | OFPS, IRC |

n, number of participants assessed at baseline; bDates of baseline assessment; cApplies to all studies; dProcedure Anomalies, recruitment in addition to typical procedures, or other deviations; eInjury severity inclusionary criterion was identical for all studies; fExclusionary criteria reductions, typical exclusionary criteria that were not applied.

TOPS-RRTC, Teen Online Problem Solving–Rehabilitation Research Training Center; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; OFPS, online family problem solving; IRC, Internet resource comparison, OMFG, online multi-family group; UC, usual care.

This project received institutional review board approval. Participant recruitment relied on review of trauma registries of participating hospitals, current hospital admissions, and outpatient medical visits, or via referral from clinical providers. Table 1 details minor study-specific deviations from this procedure and other design elements. Across studies, eligibility required overnight hospitalization for a complicated mild TBI (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score of 13–15 with positive findings on imaging), moderate TBI (lowest GCS score 9–12), or severe TBI (lowest GCS score 3–8). Current behavioral concerns were not a requirement for eligibility.

RCT design

In all five studies, participants were randomized to OFPST or one or more comparison conditions at the completion of the baseline assessment. Trained research coordinators administered assessments and questionnaires prior to randomization and at a follow-up assessment 6 months later (treatment completion). Assessments were administered in family's homes to minimize attrition. In all but one study, research coordinators were aware of group assignment at follow-up.

Treatment and control groups

OFPST

In all trials, participants randomized to OFPST began treatment 1–24 months post injury. Although the specific content and numbers of sessions varied somewhat across studies (see Table 1), OFPST consistently involved the child with TBI and at least one parent, with both parents and siblings included when possible, and provided training in cognitive reframing, problem-solving, communication skills, and behavior management. In all studies, supplemental sessions addressing specific issues (i.e., marital stress, sibling behavior, pain, or sleep difficulties) allowed families to receive content tailored to their unique concerns. After completing the core modules, families could receive up to four of these supplemental sessions as determined by the therapist and family. OFPST integrated online, didactic modules, which families completed independently, with synchronous videoconference sessions with a trained therapist. During the therapist-directed sessions, the therapist reviewed the online content with the family and facilitated problem-solving regarding a family- or child-identified goal or concern. Parents completed questionnaires assessing the child's behavior and self-reported depression and distress at baseline, before randomization, and after treatment (6 months later) in all studies.

Four RCTs used access to Internet resources for pediatric TBI as the control treatment (IRC, group), whereas one used continuation of usual psychosocial care. The IRC group received Internet access and a home page of links to online information about TBI. However, they did not have access to a study therapist or online problem-solving content. Overall, 16.16% attrition across the OFPST and control arms resulted in some follow-up data for 301 of the 359 participants with baseline data. In the IPD meta-analyses reported here, we combined IRC and usual care participants.

Measures

Outcome measures administered across studies overlapped substantially, thereby minimizing common barriers to IPD meta-analyses.22,23 Background and demographic variables used in the meta-analysis were harmonized via recoding to a common codebook.

Background interview

All studies included a parent interview regarding the child's injury, as well as medical, psychiatric, and educational history, including prior diagnoses and history of special education placement. Parents also provided information about their income and education, with the latter serving as our proxy measure of SES.

Injury information

Information abstracted from the medical chart included mechanism of injury, length of hospital stay, and lowest GCS score.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

Measures of child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were derived from the CBCL,24 a highly reliable questionnaire regarding child behavioral symptoms. The CBCL is a validated instrument that has been identified as a primary outcome for child behavioral adjustment following TBI by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Common Data Elements working group.25

Behavioral Rating Inventory of Executive Functions (BRIEF)

The Global Executive Composite (GEC) was derived from the 86 item BRIEF and used as an overall measure of everyday executive function (EF). The BRIEF is particularly suited to these studies because this instrument has been validated as a measure of behavioral regulation and metacognition in both normative and TBI samples.26,27 Parents completed the BRIEF at baseline and follow-up.

Home and Community Social Behavior Scale (HCSBS)

Child prosocial adaptive behaviors were measured via the Social Competence Scale of the HCSBS parent rating form. Parents completed this well-validated instrument (relative to other social behavior measures) at both baseline and follow-up.28

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

Parental depression was measured by the CES-D,29 a 20 item measure assessing how often the respondent experienced symptoms associated with depression over the past week. The CES-D has been used successfully across wide age ranges,30 and is sensitive to changes in depressive symptoms after intervention.31

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)

Psychological distress was measured via the Global Severity Index of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, a 90 item self-report inventory that assesses symptoms over “the past 7 days including today.” The SCL-90-R has been validated in a number of studies.32

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic, pre-morbid, and injury characteristics within each study, whereas simple summary statistic meta-analyses were used to characterize the combined studies. Linear mixed effect models were used to model four post-intervention child behavioral outcomes (BRIEF GEC, CBCL Externalizing and Internalizing Problems, HCSBS social competence) and two parent outcomes (CES-D, SCL-90 Global Severity Index [GSI]). All models were adjusted for child age, sex, race, parental education, and baseline outcome. Intent-to-treat analysis was used to preserve the benefit of randomization and to ensure unbiased estimation of the treatment effect. Study-specific random intercepts accounted for dependence of outcomes within the same study. We examined the heterogeneity of treatment effects across eight baseline variables: age, sex, race, child intelligence (IQ), pre-morbid self-reported learning disability (LD) or ADHD, parental marital status and education, and child's or parent's pre-treatment symptom levels. For each of these variables, a separate model (including an extra main effect as appropriate) was used to test its interaction with the treatment group. To address multiple comparisons, we used the less formal approach suggested by the New England Journal of Medicine special report on reporting subgroup analyses in clinical trials, by noting the number of nominally significant interaction tests that would be expected to occur by chance alone.33 Eight characteristics were examined for each of the six outcomes, resulting in 48 pre-specified subgroup analyses. An average of 2.4 statistically significant interaction tests (p < 0.05) would be expected on the basis of chance alone.

For models with significant interactions, post-hoc analyses examined treatment effects in subgroups for discrete baseline characteristics, and at the 10th and 90th percentiles for continuous baseline characteristics. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics

As reported in Table 2, study participants were, on average, 13.6 years old at injury, with a mean time since injury at enrollment in trials of 6.1 months. Approximately 40% of participants across studies had severe TBI, whereas 60% had complicated mild or moderate injuries. Table 2 also describes pre-injury history of ADHD and other emotional/behavioral problems.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics by Study; Count (%), or Mean (SD)

| Characteristic | All | Online | CDC | TOPS-Orig | CAPS | TOPS-RRTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | 359 | 43 | 42 | 41 | 132 | 101 |

| Site | ||||||

| Cincinnati | 174 (48.5) | 43 (100.0) | 42 (100.0) | 16 (39.0) | 45 (34.1) | 28 (27.7) |

| Cleveland | 62 (17.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 41 (31.1) | 21 (20.8) |

| Columbus | 57 (15.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (61.0) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (31.7) |

| Denver | 56 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (27.3) | 20 (19.8) |

| Mayo Clinic | 10 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male | 188 (62.5) | 21 (55.3) | 22 (56.4) | 17 (48.6) | 78 (65.5) | 50 (71.4) |

| White | 251 (83.4) | 28 (73.7) | 33 (84.6) | 32 (91.4) | 98 (82.4) | 60 (85.7) |

| Child Hisp/Lat Enthicity | 16 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.9) | 6 (4.5) | 8 (7.9) |

| Primary caregiver | ||||||

| Mother | 314 (87.5) | 38 (88.4) | 37 (88.1) | 38 (92.7) | 115 (87.1) | 86 (85.1) |

| Father | 34 (9.5) | 5 (11.6) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.9) | 13 (9.8) | 13 (12.9) |

| Other | 11 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.5) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (3.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Parental educationb | ||||||

| < HS | 32 (8.9) | 10 (23.3) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (7.3) | 9 (6.8) | 7 (6.9) |

| HS/GED | 136 (37.9) | 13 (30.2) | 19 (45.2) | 14 (34.1) | 52 (39.4) | 38 (37.6) |

| > HS | 191 (53.2) | 20 (46.5) | 20 (47.6) | 24 (58.5) | 71 (53.8) | 56 (55.4) |

| Parents married | 214 (59.6) | 20 (46.5) | 26 (61.9) | 28 (68.3) | 82 (62.1) | 58 (57.4) |

| Age at injury (years) | 13.6 (2.8) | 10.2 (3.2) | 11.8 (3.5) | 13.7 (2.5) | 14.5 (1.7) | 14.4 (2.1) |

| Time since injury (months) | 6.1 (5.0) | 13.4 (6.9) | 4.2 (3.2) | 9.3 (5.1) | 3.6 (1.8) | 5.7 (3.9) |

| TBI severityc | ||||||

| Severe | 141 (39.3) | 12 (27.9) | 12 (28.6) | 18 (43.9) | 51 (38.6) | 48 (47.5) |

| Moderate/Compl | 215 (59.9) | 28 (65.1) | 30 (71.4) | 23 (56.1) | 81 (61.4) | 53 (52.5) |

| ADHD Premorbidc | ||||||

| Yes | 47 (13.1) | 5 (11.6) | 7 (16.7) | 2 (4.9) | 19 (14.4) | 14 (13.9) |

| No | 309 (86.1) | 36 (83.7) | 35 (83.3) | 39 (95.1) | 112 (84.8) | 87 (86.1) |

| Other E/B Premorbidc | ||||||

| Yes | 288 (80.2) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (83.3) | 39 (95.1) | 122 (92.4) | 92 (91.1) |

| No | 26 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (16.7) | 2 (4.9) | 9 (6.8) | 8 (7.9) |

n, number of participants assessed at baseline; bparental education, reported education of the primary caregiver; cUnknown values omitted from display but included in percentage calculation.

TOPS-Orig, Teen Online Problem Solving; CAPS, Counselor Assisted Problem Solving; TOPS-RRTC, Teen Online Problem Solving–Rehabilitation Research Training Center; Hisp/Lat, Hispanic/Latino; HS, high school, GED, general education diploma, Moderate/Compl, moderate or complicated mild TBI; E/B, emotional/behavioral.

Interaction model summary

Across the 48 separate tests, we found eight significant interactions with OFPST, suggesting that age at baseline, parental education, child IQ, sex, and baseline parental depression may moderate the effect of OFPST on some of the studied outcomes at follow-up.

Child Behavior Problems

For CBCL internalizing problems, the model revealed that parental education significantly moderated the treatment effect (F = 3.62, p = 0.03; Fig. 1). Post-hoc analyses revealed significantly lower levels of post-treatment CBCL internalizing problems in the OFPST group than the control group among children of parents with a less than high school education (effect size = 0.72, p = 0.02), but no significant difference between OFPST and control groups among children of parents with higher levels of education. Age at baseline significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on CBCL externalizing problems (F = 6.42, p = 0.01; Fig. 1); on average, the OFPST group showed significantly fewer externalizing problems than the control group (effect size = 0.31, p = 0.01) among those injured at an older age (17.29 years old), whereas no group difference was found among those injured at a younger age (11.01 years old).

FIG. 1.

Least square means of Child Behavior Checklist (CBC) Internalizing and Externalizing problems by intervention group and moderators. Post-hoc analyses compared expected 6 month behavioral outcome scores (arrowhead; shaded bars indicate 95% confidence intervals) for online family problem-solving treatment (OFPST) and control conditions within each group defined by a statistically significant moderator, where the baseline score is set to the observed group-specific mean (dot); other continuous baseline variables are set at their sample-wide mean values and categorical variables are assumed to be equally prevalent; continuous moderator age at baseline is set to the 10th and 90th sample percentiles (11.0 and 17.3 years, respectively). Overall significant moderation of parental education on CBC internalizing problems (F = 3.62, p = 0.0281); the OFPST group showed on average significantly fewer internalizing problems than the Internet resource comparison (IRC) group (effect size = 0.72, p = 0.0176), among children whose parents had less than a high school education. Age at baseline significantly moderated the OFPST intervention (F = 6.42, n = 0.0109), with the OFPST group showing significantly lower externalizing problems than the IRC (effect size = - 0.31, p = 0.0135) among subjects injured at a later age.

EF behaviors

Child age at baseline significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on EF behavior at follow-up (F = 7.51, p = 0.001; Fig. 2), with no significant group differences among children injured at a younger age (11.01 years old), but significantly less executive dysfunction in the OFPST group than the control group (effect size = 0.38, p = 0.002) among those injured at an older age (17.29 years old).

FIG. 2.

Least square means of executive function and social competence by intervention group and moderators. Post-hoc analyses compared expected 6 month executive function and social competence outcome scores (arrowhead; shaded bars indicate 95% confidence intervals) for online family problem-solving treatment (OFPST) and control conditions within each group defined by a statistically significant moderator, where the baseline score is set to the observed group-specific mean (dot); other continuous baseline variables are set at their sample-wide mean values and categorical variables are assumed to be equally prevalent; continuous moderators age at baseline and IQ are set to the 10th and 90th sample percentiles (11.0 and 17.3 years, and 83 and 119 points, respectively). Age at baseline significantly moderated the OFPST intervention on executive function (F = 7.51, p = 0.0065), with the OFPST group having significantly lower Behavioral Rating Inventory of Executive Functions (BRIEF) Global Executive Composite (GEC) score than the Internet resource comparison (IRC) group, among subjects enrolled in the study at later ages. The effect of OFPST on social competence was independently moderated by parental education (F = 3.30, p = 0.0383), and child IQ (F = 10.10, p = 0.0017). Among those whose parents had less than a high school education, the OFPST group had significant better social competence (effect size = 1.00, p = 0.0015). On average, the OFPST led to significantly better social competence compared with the IRC group (effect size = 0.60, p < 0.0001) among children with lower IQ. HCSB, Home and Community Social Behavior Scale.

Social competence

Parental education significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on social competence (F = 3.30, p = 0.04, Fig. 2); the OFPST group had significantly higher social competence than the IRC group (effect size = 1.00, p < 0.01), among those whose parental education was less than high school. Child IQ also significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on social competence (F = 10.10, p = 0.002, Fig. 2). Post-hoc analyses revealed significantly higher social competence in the OFPST group than the control group (effect size = 0.60, p < .0001) among children with IQ at the 10th percentile (IQ = 83), but no significant group difference among children with IQ at the 90th percentile (IQ = 119).

GSI

Models revealed no significant moderation of the effect of OFPST on the GSI at follow-up by any of the eight baseline characteristics. However, based on a model with no interactions, the GSI was significantly lower overall at follow-up for the OFPST group than for the control group (effect size = 0.21, p = 0.02).

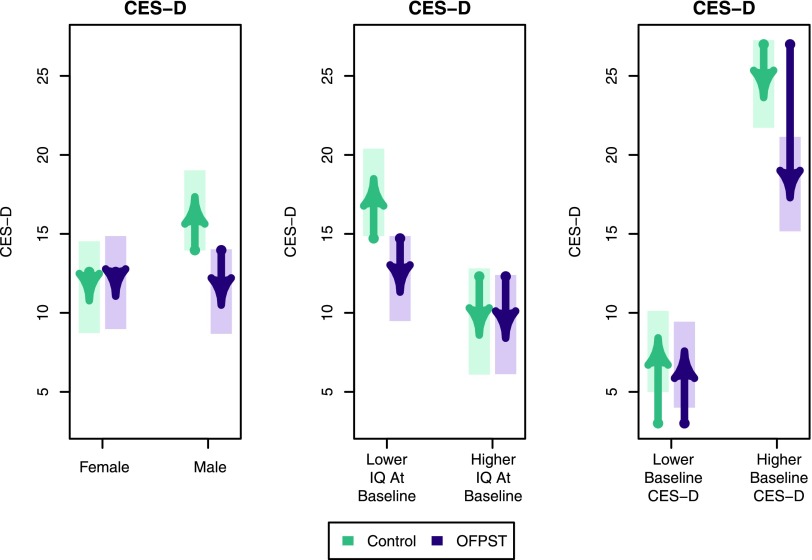

CES-D

Child sex, IQ, and baseline CES-D score significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on parental depression at follow-up (see Fig. 3). Among boys, the OFPST group showed significantly lower parental CES-D scores than the control group (effect size = 0.51, p < 0.0001), but no group difference in parental CES-D was found among girls. Among children with IQ at the 10th percentile (IQ = 83), the OFPST group demonstrated significantly lower CES-D than the control group (effect size = 0.54, p = 0.0004), whereas no significant group difference was found among children with IQ at the 90th percentile (IQ = 119).

FIG. 3.

Least square means of parental depression by intervention group and moderators. Post-hoc analyses compared expected 6 month parental depression outcome scores (arrowhead; shaded bars indicate 95% confidence intervals) for online family problem-solving treatment (OFPST) and control conditions within each group defined by a statistically significant moderator, where the baseline score is set to the observed group-specific mean (dot); other continuous baseline variables are set at their sample-wide mean values and categorical variables are assumed to be equally prevalent; continuous moderators IQ and baseline Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) are set to the 10th and 90th sample percentiles (83 and 119 points and 3 and 27 points, respectively). The effect of OFPST on parental depression was significantly moderated by child gender (F = 7.94, p = 0.0052), IQ (F = 4.46, p = 0.0355), and baseline parent CES-D (F = 5.68, p = 0.0178). The OFPST group showed significantly lower parental depression than the Internet resource comparison (IRC) group among males (effect size = 0.51, p < 0.0001), subjects with lower IQ (effect size = 0.54, p = 0.0004), and high baseline parental depression score (effect size = 0.62, p = 0.0002)

The effect of OFPST on CES-D was also significantly moderated by the baseline CES-D score (F = 5.68, p = 0.0178). Parents with baseline CES-D scores at the 90th percentile (CES-D = 27) in the OFPST group showed on average significantly lower CES-D scores at follow-up than those in the control group (effect size = 0.62, p = 0.0002), whereas parents who had lower CES-D at baseline (baseline CES-D of 3) showed no group difference in post-treatment CES-D scores.

Discussion

We adopted an IPD meta-analysis approach to characterize treatment effects across studies and to identify subgroups that are likely to benefit from the OFPST intervention. We conducted subgroup analyses for eight baseline participant characteristics and six child behavioral and parent outcomes. These analyses, involving >300 children and adolescents, partially supported prior findings regarding the moderating role of age, SES, and baseline symptom levels, while suggesting that other factors such as child IQ and sex may also influence treatment efficacy. As will be described in greater detail, these findings shed new light on who benefits from OFPST following pediatric TBI.

Consistent with hypotheses and prior findings from the individual RCTs, parental education significantly moderated the efficacy of OFPST, with children of parents with a less than high school education exhibiting fewer internalizing problems and better social competence after this intervention than children in the control group. In prior studies, parental SES moderated treatment effects on externalizing behaviors, but the current meta-analyses painted a different picture by finding moderating effects on internalizing behaviors.34 In cohort studies, SES has been associated with behavior problems following TBI, with children from families of lower SES experiencing higher levels of behavior problems. The opportunity for more improvement in behavior in children from lower SES families, as well as potentially poorer problem-solving skills in their parents, may increase their likelihood of benefiting from OFPST.12

Child's age at baseline also significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on externalizing problems and executive dysfunction, with children injured at an older age exhibiting fewer externalizing behaviors and less executive dysfunction following OFPST. This finding parallels the results of those individual studies that included a wider age range of participants, and suggests that OFPST may be particularly well suited to adolescents.13,16,35 The greater capacities of adolescents, relative to younger children, to regulate their own behavior may help them take greater advantage of the problem-solving strategies taught as part of OFPST.

The effect of OFPST on social competence was moderated by child IQ, with pronounced effects of OFPST on children with lower IQ, whereas there was no statistically significant effect for children with higher IQ. Children with lower IQs in the control groups demonstrated lower than average social competence at follow-up, suggesting that TBI coupled with intellectual impairment may be associated with poorer social competence, which in turn might be at least partially ameliorated by OFPST. These findings again support the notion that children at greater risk for impairment either because of lower SES or lower IQ may be more able to benefit.

Child IQ, sex, and baseline parental CES-D score significantly moderated the effect of OFPST on parental depression at follow-up, with lower levels of depression following OFPST found among subgroups with lower IQ, boys, and children of parents with higher depression scores at baseline. The association between higher levels of parental depression pre-treatment and greater improvement after treatment is consistent with prior research.36 The pattern in Figure 3 suggests that some of the decrease in CES-D score may be the result of regression to the mean, but this phenomenon would not explain the differential improvement between treatment groups. Associations of child IQ and sex with parental depression at follow-up were unanticipated, and may in fact reflect correlation with baseline CES-D rather than separate effect moderation.

Some factors that had been shown to influence outcomes in prior studies (e.g., caregiver marital status) and other exploratory factors, such as race and premorbid LD or ADHD,19 were not found to moderate the effect of OFPST on child behavioral outcomes or parental depression. These findings are encouraging, and provide preliminary evidence that OFPST is equally beneficial regardless of race or pre-morbid diagnoses. Additionally, they contradict findings from a single previous study that suggested that children of single parents were less likely show improvement following OFPST.

This IPD meta-analysis provides an evidence base regarding subgroups that were likely to benefit from OFPST, and could be used to inform a future precision medicine approach for children following pediatric TBI. Our findings indicate that the optimal application of OFPST is likely to involve older children, those with lower IQ scores, or those from families with lower SES. OFPST was not found to be beneficial in terms of child behavior at follow-up among children injured at an early age, children from higher SES homes, or children with higher IQ scores. Younger children likely need alternative treatment that is less reliant on their own metacognitive abilities. Children of higher SES or those with higher IQs may have less need for OFPST because they may have higher neurocognitive reserves, and environmental factors may be more optimized, leading to fewer behavioral challenges following their injuries. Because the OFPST studies did not exclude children who were not experiencing difficulties, a subset of the participants likely did not require treatment. This supposition is consistent with the average level of symptoms falling in the average range at baseline. Although the factors driving parental benefit overlapped with those associated with child improvement (e.g., child IQ), pre-treatment parent symptom levels and child sex also played a role, suggesting that different constellations of factors contribute to OFPST efficacy for parent and child outcomes. These findings raise the possibility that families that do not experience improvements in child behavior may still derive benefits in terms of reduced parental depression.

Given the lack of evidence-based treatments for pediatric TBI, these findings have important clinical implications. While confirming the value of OFPST for improving child behavioral and family consequences, they underscore that children and families who are more vulnerable to persistent difficulties because of social disadvantage or intellectual impairments should be targeted for treatment. Additionally, screening parents for depression and linking those with elevations to treatment may further reduce morbidity.

Study limitations

Like many other clinical trials, none of the five trials was designed to detect significant heterogeneity in treatment effects. The combined sample size from the five trials may also fall short in this respect, as detection of statistically significant heterogeneity in treatment effects may require an even larger sample size. Although the lack of statistical power limited our ability to conduct a formal subgroup analysis that adjusted for multiple comparisons, our report of the number of nominally significant interaction tests that would be expected to occur by chance alone is in accordance with a New England Journal of Medicine special report on reporting subgroup analyses in clinical trials. Our analyses resulted in 8 significant interactions, whereas an average of 2.4 significant interaction tests would be expected by chance. In addition to p values, we also reported the effect sizes as a measurement of substantive significance. Pre-morbid learning and attention problem information was based on self-reported data, and may be subject to recall bias. There were slight variations in the five studies in terms of exclusionary criteria, subject recruitment, control group, and actual deliveries of the OFPST intervention, and this was accounted for through random effects.

Conclusions

The current findings add to the limited literature on evidence-based treatments for behavioral challenges following pediatric TBI, and inform the delivery of family-centered treatments that involve the child with TBI. The results suggest that family-centered OFPST is likely to benefit children injured at later ages, with lower IQs, or from lower SES families. Precision medicine is a concept that incorporates individual variability, including variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle, to identify the optimal management approach for each individual.37,38 The current findings inform a precision medicine approach for delivery of OFPST after pediatric TBI by defining the baseline characteristics of children and parents most likely to benefit from OFPST. Future studies are needed to identify other characteristics that moderate treatment outcomes, such as genetic and environmental factors. Overall, our findings can be used to inform clinical delivery of OFPST and other family-centered treatments for children with TBI.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1R21HD089076-01. Data from the following clinical trials were used in this study: An On-Line Intervention for Families Following Pediatric TBI, conducted prior to trial registration; A Trial of Two On-Line Interventions for Child Brain Injury, NCT00178022, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00178022?term=NCT00178022&rank=1; Teen Online Problem Solving (TOPS) – An Online Intervention Following TBI (TOPS), NCT00409058, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00409058?term=NCT00409058&rank=1; Improving Mental Health Outcomes of Childhood Brain Injury (CAPS), NCT00409448, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00409448?term=NCT00409448&rank=1; and Rehabilitation Research and Training Center for Traumatic Brain Injury Interventions – Teen Online Problem Solving Study (RRTC—TOPS), NCT01042899, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01042899?term=NCT01042899&rank=1 We acknowledge the contributions of Amy Cassedy, Ph.D. and Nori Minich, B.S. to data cleaning and synthesis; the contributions of Jennifer Taylor, B.A. to regulatory oversight, and the contributions of Aimee Miley, B.A, B.S. to manuscript preparation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Emery C.A., Barlow K.M., Brooks B.L., Max J.E., Villavicencio-Requis A., Gnanakumar V., Robertson H.L., Schneider K., and Yeates K.O. (2016). A systematic review of psychiatric, psychological, and behavioural outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents. Can. J. Psychiatry 61, 259–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ilie G., Boak A., Adlaf E.M., Asbridge M., and Cusimano M.D. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of traumatic brain injuries among adolescents. JAMA 309, 2550–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Max J.E., Wilde E.A., Bigler E.D., MacLeod M., Vasquez A.C., Schmidt A.T., Chapman S.B., Hotz G., Yang T.T., and Levin H.S. (2012). Psychiatric disorders after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a prospective, longitudinal, controlled study. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 24, 427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams W.H., Mewse A.J., Tonks J., Mills S., Burgess C.N., and Cordan G. (2010). Traumatic brain injury in a prison population: Prevalence and risk for re-offending. Brain Inj. 24, 1184–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bombardier C.H., Fann J.R., Temkin N.R., Esselman P.C., Barber J., and Dikmen S.S. (2010). Rates of major depressive disorder and clinical outcomes following traumatic brain injury. JAMA 303, 1938–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Visser S.N., Danielson M.L., Bitsko R.H., Holbrook J.R., Kogan M.D., Ghandour R.M., Percu R., and Blumberg S.J. (2014). Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53, 34–46e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Max J.E., Schachar R.J., Levin H.S., Ewing-Cobbs L., Chapman S.B., Dennis M., Saunders A., and Laudis J. (2005). Predictors of secondary attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents 6 to 24 months after traumatic brain injury. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 44, 1041–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narad M.E., Yeates K.O., Taylor H.G., Stancin T., and Wade S.L. (2017). Maternal and paternal distress and coping over time following pediatric traumatic brain injury. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 42, 304–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wade S.L., Taylor H.G., Yeates K.O., Drotar D., Stancin T., Minich N.M., and Schluchter M. (2006). Long-term parental and family adaptation following pediatric brain injury. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 31, 1072–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wade S.L., Carey J., and Wolfe C.R. (2006). An online family intervention to reduce parental distress following pediatric brain injury. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74, 445–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wade S.L., Walz N.C., Carey J., McMullen K.M., Cass J., Mark E., and Yeates K.O. (2011). Effect on behavior problems of teen online problem-solving for adolescent traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 128, e947–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wade S.L., Walz N.C., Carey J., and McMullen K.M. (2012). A randomized trial of teen online problem solving: efficacy in improving caregiver outcomes after brain injury. Health Psychol. 31, 767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wade S.L., Karver C.L., Taylor H.G., Cassedy A., Stancin T., Kirkwood M.W., and Brown T.M. (2014). Counselor-assisted problem solving improves caregiver efficacy following adolescent brain injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 59, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wade S.L., Stancin T., Kirkwood M., Brown T.M., McMullen K.M., and Taylor H.G. (2014). Counselor-assisted problem solving (CAPS) improves behavioral outcomes in older adolescents with complicated mild to severe TBI. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 29, 198–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wade S.L., Kurowski B.G., Kirkwood M.W., Zhang M., Cassedy A., Brown T.M., Nielson B., Stancin T., and Taylor H.G. (2015). Online problem-solving therapy after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 135, e487–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wade S.L., Taylor H.G., Cassedy A., et al. (2015). Long-term behavioral outcomes after a randomized, clinical trial of counselor-assisted problem solving for adolescents with complicated mild-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wade S.L., Carey J., and Wolfe C.R. (2006). The efficacy of an online cognitive-behavioral, family intervention in improving child behavior and social competence following pediatric brain injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 51, 179–189 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wade S.L., Cassedy A.E., Fulks L., Taylor H.G., Stancin T., Kirkwood M.N., Yeates K.O., and Kurawski B.G. (2017). Problem solving following traumatic brain injury in adolescence: associations with functional outcomes. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98, 1614–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raj S.P., Zhang N., Kirkwood M.W., Taylor H.G., Stancin T., Brown T.M., and Wade S.L. (2017). Online family problem solving for pediatric traumatic brain injury: influences of parental marital status and participation on adolescent outcomes. 33, 158–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simmonds M., Stewart G., and Stewart L. (2015). A decade of individual participant data meta-analyses: a review of current practice. Contemp. Clin. Trials 45(Pt A), 76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stewart L.A., and Parmar M.K. (1993). Meta-analysis of the literature or of individual patient data: is there a difference? Lancet 341, 418–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abo-Zaid G., Sauerbrei W., and Riley R.D. (2012). Individual participant data meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies: state of art? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson A. (2009). Thinking big: large-scale collaborative research in observational epidemiology. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 24, 727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Achenbach T.M., and Rescorla L.A. (2001). Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families: Burlington, VT [Google Scholar]

- 25. NINDS (2013). NINDS Common Data Elements: Traumatic Brain Injury CDE Standards. https://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/TBI.aspx#tab=Data_Standards (Last accessed April18, 2018)

- 26. Gioia G.A., and Isquith P.K. (2004). Ecological assessment of executive function in traumatic brain injury. Dev. Neuropsychol. 25, 135–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCarthy M.L., MacKenzie E.J., Durbin D.R., Aitken M.E., Jaffe K.M., Paidas C.M., Slomine B.S., Dorsch A.M., Berk R.A., Christensen J.R., Ding R., and CHAT Study Group. (2005). The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory: an evaluation of its reliability and validity for children with traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86, 1901–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Merrell K.W., and Caldarella P. 2002). Home and Community Social Behavior Scales Users' Guide. Paul H. Brookes Pub. Company: Baltimore [Google Scholar]

- 29. Radloff L.S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewinsohn P.M., Seeley J.R., Roberts R.E., and Allen N.B. (1997). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol. Aging 12, 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinquart M., and Sorensen S. (2006). Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int. Psychogeriatr.18, 577–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Derogatis L.R., and Savitz K.L. (2000). The SCL-90-R and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in primary care, in: Handbook of Psychological Assessment in Primary Care Settings. Maruish M.E. (ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, pps. 297–334 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang R., Lagakos S.W., Ware J.H., Hunter D.J., and Drazen J.M. (2007). Statistics in medicine — reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2189–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wade S.L., Taylor H.G., Yeates K.O., Kirkwood M., Zang H., McNally K., Stacin T., and Zhang N. (2018). Online problem solving for adolescent brain injury: a randomized trial of 2 approaches. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 39, 154–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wade S.L., Stancin T., Kirkwood M., Brown T.M,. McMullen K.M., and Taylor H.G. (2013). Counselor-Assisted Problem Solving (CAPS) improves behavioral outcomes in older adolescents with complicated mild to severe TBI. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 29, 198–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petranovich C.L., Wade S.L., Taylor H.G., Cassedy A., Stantin T., Kirkwood M.W., and Brown T.M. (2015). Long-term caregiver mental health outcomes following a predomincately online intervention for adolescents with complicated to mild severe traumatic brain injury J. Pediatr. Psychol. 40, 680–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tonelli M.R. and Shirts B.H. (2017). Knowledge for precision medicine mechanistic reasoning and methodological pluralism. JAMA 318, 1649–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Collins F., and Varmus H. (2015). A new initiative on precision medicine N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 793–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]