Abstract

Background: Integrative health is an expanding field that is increasingly called upon by conventional medicine to provide care for patients with chronic pain and disease. Although evidence has mounted for delivering integrative therapies individually, there is little consensus on how best to deliver these therapies in tandem as part of whole person care. While many models exist, few are financially sustainable.

Methods and results: This article describes a conceptual and logistical model for providing integrative outpatient health care within an academic medical center or hospital system to patients with chronic pain and disease. In hopes that the model will be replicated, administrative details are provided to explain how the model operates and has been maintained over nine years. The details include the intentional building of a particular work culture.

Conclusion: This whole person care model that addresses chronic pain and disease in an outpatient integrative clinic has been successful, sustainable and can be replicated in other academic medical centers or hospital clinics.

Keywords: chronic pain, relationship-centered care, whole person care, integrative health, mind–body therapies, Core Resonance

Need for Sustainable Integrative Health Delivery Models

Demand for Integrative Health Care (IH) that treats the whole person, using whole practices and whole systems, continues to grow as compelling evidence emerges that IH can reduce personal suffering and societal cost. The promise of IH is particularly salient in the new conventional medicine guidelines that recommend IH to address chronic pain and the devastation left in the wake of the overlapping obesity and opioid crises.1 IH creates a viable pathway to moderate chronic pain and disease2–4 and may also reduce cost.5,6 Despite these promises, however, the dearth of implementation research on IH and the lack of an effective and viable clinical model challenge the sustainability of IH. Using an academic IH model that has been both clinically and financially successful for nine successive years, this article presents a replicable strategy to establish the structure, operations, and necessary culture to build and sustain an IH academic clinic in an insurance-based care system.

The health care system is struggling to provide alternative treatment options in the current epidemic of chronic pain and the opioid crisis. Chronic pain impacts over one third of the U.S. population (1.5 billion worldwide), is the primary cause for disability in Americans, and the societal costs are estimated as high as 635 billion dollars per year in the United States alone.7 Hand-in-hand with the chronic pain epidemic are the concurrent rising rates of opioid misuse and addiction, combined with emerging evidence that opioids increase health care utilization and psychologic distress.8

This constellation of factors underscores the need for an approach to chronic pain that is not reliant on opioids. Furthermore, as providers in every specialty face the challenge of treating patients with chronic pain without effective treatments or systems to appropriately care for these patients, the need for transdisciplinary approaches becomes more striking. Perhaps this is why chronic pain is the number one condition for which patients seek IH.9,10

To date, the most effective evidence-based treatments to chronic pain utilize a biopsychosocial interdisciplinary approach.8 Nonetheless, multiple barriers threaten the implementation and sustainability of care involving multiple disciplines working with a patient synergistically. For example, despite the well-documented long-term cost savings of an IH model,3,11 one often-cited barrier is the “up-front” cost. Additional barriers include a “lack of sufficient time to train and organize clinic staff and the absence of a unifying model of pain care.”8

A transdisciplinary model builds upon an interdisciplinary model by having team members jointly collaborate, include the patient in planning and defining the plan by systems or areas of health instead of disciplines.12 The promise of an integrative, transdisciplinary, relationship-centered model of care fits neatly with the needs of chronic pain treatment. Below the authors detail the background of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Vanderbilt (OCIM), including its conceptual framework and operational underpinnings. OCIM provides a replicable, effective, and sustainable care model for treatment of chronic pain.

Background and Overview of the Clinic

History

This clinic was founded in 2007 for the purpose of bringing the benefits of IH into the academic environment. The two founders shaped the delivery of care at the center; one was a physician with a background in palliative care, internal medicine, and exposure to mindfulness and the other a health psychologist with experience in traditional healing systems and treating psychologic trauma. Both began with part-time practices in IH while maintaining their primary clinics on main campus. Over time, as demand grew, their practices became entirely IH supported by a growing team providing massage therapy, acupuncture, and physical therapy (PT) and eventually health coaching, mindfulness, hypnosis, yoga, and t'ai chi.

Clinical population

OCIM is an integrative clinic that cares for patients with complex chronic pain who typically have histories of extensive psychologic trauma. Entry to the clinic requires the presence of a medical diagnosis. Commonly, psychiatric diagnoses accompany presenting medical conditions and can both precede and develop following the onset of chronic illness. OCIM does not accept patients with only a psychiatric diagnosis. This process manages referral streams and optimizes the patients who will likely benefit from all forms of treatment available in the clinic, including PT and health-specific psychology groups (e.g., those focused on illness coping and pain management).

The most common conditions seen involve musculoskeletal pain conditions, neuropathic pain conditions, gastrointestinal disorders, and patients often present with comorbid mental health conditions and insomnia. For example, in a sample of 2214 consecutive patients who presented to the clinic, the top three self-reported primary complaints were pain, anxiety, and fatigue. The clinic serves a chronic pain population in a state with the third highest opioid prescribing rate.13 The practitioners do not prescribe opioids; however, the population includes both opioid and nonopioid dependent patients. Specifically, an estimated 18% of the clinic's population has a prescription for an opioid and roughly 8% take an opioid on a daily basis.

The clinic provides specialty IH outpatient services, and over 85% of the patients are referred by providers within the academic medical center. The top three referring departments are internal medicine, interventional pain, and neurology. The clinic uses the Vanderbilt version of Epic for their electronic medical record. Care is provided for patients aged 12 and up. The clinic does not provide primary care or laboratory services.

Clinic size

The clinic is situated on the edge of the main medical center campus of a private academic medical center in the Southeast. It is self-contained and began with 3800 square feet. As a result of growing interest and need, it nearly doubled in size in 2011 and then doubled again in 2017 to its current almost 16,000 square feet. In terms of the volume of the clinic, over 17,000 patient visits occurred in 2017. There is often a 6-month minimum wait for their services. While the patient demand is clearly strong, the administration tempers the growth in personnel to ensure that the personnel adequately cultivates the culture and the clinic delivery model as it grows.

Conceptual model

According to the University of Arizona, “Integrative Medicine (IM) is healing-oriented medicine that takes account of the whole person, including all aspects of lifestyle. It emphasizes the therapeutic relationship between practitioner and patient, is informed by evidence, and makes use of all appropriate therapies.”14 The more recently-minted definition of Integrative Health, aligned with that of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), then adds the dimensions of social determinants and additional systems “beyond the clinic” to the above definition, widening the scope to a focus on cultivation of health and well-being by self-empowered individuals.15,16 Taken together, the clinic approaches care informed by three key tenets: providing integrative whole person therapies, leveraging relationship as the conduit for healing, and providing care in a transdisciplinary model. A process called Core Resonance™ (unpublished data, described later) was used to elucidate these tenets.

Operational Model

Financial model

Gifted funds were used for building the initial space, salary, and operation support from 2007 to 2009 as the clinic began. No gifted funds have been used for clinical operations since 2009. As an outpatient hospital clinic, a portion of their revenue is from fees generated by the hospital for facility services, an important contributor to fiscal sustainability. Another portion is from the professional services delivered by the billing provider. A third portion is cash from noninsurance services. Contracts with insurance companies are negotiated at the institutional level. Over the 11 years the clinic has been open, collection rates from insurance have dropped from 64% to 46%. Due to their last expansion, their status with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) changed, and the clinic is no longer able to bill Medicare for technical fees. Overall, the mix of patients with different insurance types is similar to that of the medical center with ∼57% commercial, 21% Medicare, 19% private pay, 3% third party and workers compensation, and 2% other. As a percentage of total revenue, professional fees are 21%, technical fees (includes PT) 67%, acupuncture and massage 9%, and classes and workshops 3% (See Core Staffing for billing codes typically used.) One of the keys to the steady and sustainable growth is the way the clinic onboards new team members. When possible, the clinic brings providers onboard at a partial full-time equivalent (FTE) until their clinical time is full and then gradually increases the clinical time up to 0.75 FTE.

Operationalizing the treatment model in an insurance-based system

Since the model serves patients with complex physical, psychological, and psychosocial challenges, integrative providers must find ways to collaborate effectively. As seen in Table 1, the treatment model includes many specialties commonly seen in IH clinics, including acupuncture, massage, yoga, t'ai chi, and mindfulness-based interventions. However, given their concerted effort to provide integrative mind–body practices within an insurance-based model, the clinic also utilizes providers that may be less common in typical IH practices, but who can bill insurance for the integrative therapies they offer. In particular, the clinic optimizes use of nurse practitioners (NPs), physical therapists, and health psychologists. NPs who are also trained as health coaches provide integrative consults and follow-up visits that focus on nutrition, health coaching, mind–body practices, and biofeedback. Health psychologists lead mindfulness and hypnosis groups, as well as provide individual therapy. PTs include manual therapy, health coaching principles, and breathing practices in their treatment. Often, two professionals from different disciplines facilitate group services together. For example, IH groups are co-led by a movement practitioner and psychologist who bills the session or by a yoga therapist and NP, who bills the session. All clinicians who see patients are required to chart in the electronic medical record regardless of whether or not their services were directly billed.

Table 1.

Clinical Staffing

| Profession/role | Classification | cFTE | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health coach | Faculty | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| Health psychologist/behavioral health therapist | Faculty | 2.05 | 1.75 | 3.80 |

| Massage therapist | Staff | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| Medical NP | Faculty | 0.90 | 0.60 | 1.50 |

| Physical therapists | Staff | 1.40 | 0.10 | 1.50 |

| Physician | Faculty | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.60 |

| Psychiatric NP | Faculty | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.80 |

| Registered nurse | Staff | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| T'ai Chi instructor | PRN | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| TCM acupuncturist | Faculty | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| Yoga therapists | PRN | 1.20 | 1.20 | |

| Students (Masters intern, post doc)a | Trainees | 1.75 | 0.25 | 2.00 |

| Administrative staff | Staff | 8.00 | 8.00 |

“Other” includes time allocated to research, teaching, or program development.

Can't bill yet so see the patients without insurance or resources.

cFTE, clinical full-time equivalent; NP, nurse practitioner; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Core staffing

The clinic draws heavily on three disciplines: nursing, health psychology, and PT.

Nurse practitioners

Due to their unique training and focus on the whole person, NPs form a cornerstone of the IH model as they acknowledge each patient's unique health status and goals and work with them to promote wellness through behavior change and integrative therapies. The model aligns well with the American Association of Nurse Practitioners' (AANP) description of NPs: “What sets NPs apart from other health care providers is their unique emphasis on the health and well-being of the whole person. With a focus on health promotion, disease prevention, and health education and counseling, NPs guide patients in making smarter health and lifestyle choices.”17

The clinical model is built to improve the level of function and quality of life of patients. Part of the role of the medical team is to determine if a patient has had an appropriate workup for their health issue to ensure that there are no underlying conditions requiring specialty care. This model has less emphasis on diagnosing and curing and more emphasis on lifestyle, behavior change, and healing. When someone has cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or migraines, they benefit from the disease modifying treatments offered by the specialties of cardiology, rheumatology, and neurology. These patients can also benefit from making sustainable lifestyle change, using nonpharmacologic approaches to pain, and optimizing health regardless of disease. These things are not mutually exclusive. The clinical care model emphasizes the latter.

It is also worth noting that outcomes for NPs are consistently comparable to and in some cases exceed that of their physician colleagues,18,19 making them an appropriate choice to provide high quality care to their patients and provide meaningful contributions to their team. In addition, the cost of staffing a clinic using NPs is considerably less than staffing with physicians. The medical/nursing team primarily bill evaluation and medical codes (CPT codes 99201-5) for new consults and for follow-up visits (CPT 99211-5).

Health psychologists

The National Pain Strategy recommends psychosocial intervention as a first-line treatment for chronic pain, applied in the context of multimodal care.20 Interventions delivered to chronic pain patients by licensed mental health providers, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, self-management, mindfulness-based treatments, and clinical hypnosis, reduce pain intensity, improve function, quality of life, and well-being, and increase chances of patients returning to work.21–26 Health psychologists assist patients with adjusting to and accepting illness and learning to anticipate and reduce proclivity to symptom escalations, often through learning specific skills to prevent, cope with, and reduce chronic pain and illness.27 Moreover, addressing comorbid depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress associated with illness can also reduce its burden on pain symptoms and improve treatment adherence and follow-through. In the IM setting, mental health practitioners deliver skill-based groups (e.g., mindfulness and clinical hypnosis), pain psychoeducation, and individual psychotherapy to address psychosocial factors that influence illness expression. Importantly, since these services address factors that impact the recovery or progression of a diagnosed physical health problem or illness, they fall under “Health and Behavior Assessment and Intervention” Centers of Medicaid and Medicare Services billing guidelines (CPT codes 96150-4). The clinic has found that using these billing codes rather than conventional psychotherapy codes positively impacts its bottom line.

Physical therapists: restoring function

Compared to conventional PT practices, PT in an IH setting has several key differences. While both models are insurance based and require identical documentation and coding for reimbursement, the delivery of PT as part of the relationship-centered, transdisciplinary IH model is unique. First, conventional PT typically focuses on the evaluation and treatment of acute orthopedic and/or neurologic conditions, while IH PT typically addresses chronic conditions and/or widespread pain. Second, conventional PT is often performed in a gym setting, with care provided by a rotating team that includes physical therapists, PT assistants, athletic trainers, and/or technicians. IH PT is provided in a private treatment room by a licensed physical therapist only. While there is not a specific certification for IH physical therapists, the complexity of their patient population requires a high level of professional experience and advanced training in manual therapy techniques. The IH physical therapists average 25 years of experience in the field and complete an average of 15 h of continuing education each year to advance their manual therapy skills. In the IH setting, care is taken to ensure a safe and comfortable environment for patients. Consistency of PT providers is maintained, and dimmer switches, sound machines, and weighted blankets are used to enhance patient comfort. Third, provider to patient ratios for the IH clinic PT are always 1:1, compared with 1:2–3 in traditional PT settings. Fourth, IH PT sessions are often longer than in conventional PT clinics. IH PT sessions are 50 min and typically provided 1–2 times/week for 12–18 weeks, depending on the patient's individualized treatment plan. Finally, while conventional PT is often protocol driven, IH PT emphasizes functional restoration through patient education, gentle movement, and manual therapy. Patient education may include the following: diagnosis management, training in posture and body mechanics, sleep hygiene, pacing and energy conservation, relaxation techniques, including diaphragmatic breathing, home exercise instruction and progression, as well as basic nutrition/hydration principles. Manual therapy techniques performed by IH physical therapists include: myofascial release, soft tissue mobilization, trigger point release, and joint mobilizations. Movement interventions vary significantly between patients but emphasize a gentle progression of exercises to promote flexibility, core strength, and postural stabilization, with the long-term goal of transition to an independent practice at home or in a group setting. The clinic partners with the yoga and t'ai chi instructors to transition patients to long-term maintenance movement. The most commonly billed services (and their CPT codes) for PT include: PT Evaluation-Moderate Complexity (CPT 97162), PT Evaluation-High Complexity (CPT 97163), Therapeutic Exercise (CPT 97110), Manual Therapy (CPT 97140), and Aquatic Therapy (CPT 97113).

IH therapies

In addition to the above services, the clinic provides acupuncture, yoga, and t'ai chi. Thirty-percent is covered by worker's compensation benefits and Veteran's Administration benefits; 70% is paid directly by the patient. The clinic's acupuncturist attended medical school in China and specialized in Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). In the clinic, he assesses using TCM and administers acupuncture. While he makes recommendations for other TCM therapies, he does not dispense these in the clinic. Moxibustion, for example, is not allowed in the building due to fire codes. In the electronic medical record, he documents both biomedical and TCM diagnoses.

Certified yoga teachers offer yoga in the center both as an individual and as a group service. The clinic's teachers have diverse training from Hatha, Iyengar, and T. Krishnamacharya traditions. The teachers gear their yoga classes to patients who have extensive surgical and medical conditions that limit their ability to participate in community yoga. About half of the yoga groups (4–5 of 10/week) are covered by the employee health plan when patients are employees and have specific diagnoses (i.e., low back pain or insomnia). Protocols for these diagnosis-specific yoga groups were designed by a team of two with training in yoga therapy; one is a yoga teacher and the other an internal medicine physician. In addition, yoga at the clinic is typically included in the integrative medicine group visits and chronic pain classes, both of which are billed to insurance by NPs. All other yoga services are charged directly to the patient.

T'ai chi services at the clinic are unfortunately not covered by insurance plans. The clinic offers t'ai chi for balance class and a series of classes geared toward more advanced students. Their t'ai chi instructor trained in China at the Shanghai University of TCM is currently under the teaching of Master Yang Jun, the lineage holder of the Traditional Yang style Tai Chi Chuan. She is certified by the American Tai Chi and Qigong Association (ATCQA) as a t'ai chi and qigong instructor. She also holds a doctorate in instruction and administration. The t'ai chi instructor practices the Yang style of t'ai chi, teaches this traditional form, as well as customized programs that emphasize body awareness, mind–body connection, and preventive health with practices that focus on tension release, dynamic weight shifting, coordination, waist initiated movements, effortless and purposeful movements, qigong self-massage, and energy cultivation.

Transdisciplinary cohesion

To provide transdisciplinary care, organizational structure intentionally supports formal and informal collaboration among providers, as well as between caregivers and support staff who interact with the patients. Table 2 provides an overview of the transdisciplinary collaboration. In addition, a formal biennial retreat to develop common language and identify shared values is used to align team members in their orientation to healing and collaboration. Since 2014, the clinic's center has used a process called Core Resonance to elicit and anchor the core or unifying values of the team as the central tenets of its philosophy of healing and transformation. Core Resonance is a facilitated process that serves as a means for identifying and articulating the core values and to foster alignment in mission, purpose, and action. The process is designed to tap into something larger than any one person to transcend territory, turf, and agenda. The clinic uses Core Resonance as a tool to engage every member of the team and ensure that each person has an opportunity to contribute to philosophy and direction. The process reinforces the culture, as well as provides a tangible means for new members to identify their connection to the core values. It bears some resemblance to strategic planning, but instead of producing specific action steps it activates internal resonance with their values and ideals. The clinic uses the components that come from the process as a filter for addressing issues that arise, questions that need group or individual input, and decisions about center priorities and strategy. Core Resonance is a biennial touch point that helps us align the mission, vision, values, and language. Furthermore, all center directors have undergone additional training in how to use the components, as well as develop their own personal Core Resonance statements. The core components identified by the clinic's team using this process are presented in Table 3. To further support the mission of modeling wellness in caring for the clinic's challenging population and ourselves, self-care practices are encouraged and made available to all employees, including optional weekly meditation, walking meetings, and social gatherings.

Table 2.

Formal and Informal Collaboration

| Formal collaboration | Informal collaboration |

|---|---|

| Weekly 1 h clinical team meeting—all providers are paid to attend, including contractors. | Templates structured on 70% productivity provide time to complete charting, attend meetings, and have informal collaboration with team. |

| Discipline specific team meetings—4 h/month | Clinicians leave doors open when not with patient to promote “hallway consults.” |

Table 3.

Core Components of Their Conceptual Framework

| Whole-person therapies |

| Engage the whole person in accessing their natural capacity for health and healing |

| Transformative care guided by the individual's journey |

| Leveraging relationship as the conduit for healing |

| Relationship-centered care in a healing environment |

| Focus on the patient, the practitioner, and the healing environment |

| Care for ourselves so the clinic can best serve its patients |

| Care for their Center so the clinic can best serve its patients |

| Honor and support the relationship in all aspects of the health and healing process. |

| Transdisciplinary model |

| Interprofessional team-based model |

| Integrating clinical care, education, training, and research |

| Transformative care informed by continuous quality improvement |

Productivity model supports cohesion

Implementing a model that promotes relational coordination improves productivity, job satisfaction, and collaborative knowledge creation and reduces burnout.28,29 Nonetheless, the demands of providing care within the modern health care system challenge the practitioners' ability to model wellness and maintain strong professional relationships. A relational approach requires protected time. The clinic's leadership consistently observed that clinicians tasked with 100% clinical time quickly feel overwhelmed and are at risk for burnout. At the same time, ample evidence demonstrates that spending more time with patients results in better outcomes.30–32 To balance the time demands, the clinic hires new practitioners at 70%–80% FTE for clinical effort. The remaining 20%–30% is dedicated to specific education, research, or administrative targets or a modified schedule based on personal goals, priorities, and professional development needs. Clinical schedules are structured to provide time for team meetings, charting, informal collaboration, and projects. Depending on the provider's FTE, as much as 10%–25% of the clinical time is allotted for such purposes. See Table 1 for a staffing breakdown. In the clinic's office, the doors typically remain open when we are not with patients to promote in-the-moment updates from other clinicians. By modeling a work environment that promotes balance, communication, and self-care, the clinic cultivates clinicians who are able to be present and engaged with their patients.

Clinical flow supports cohesion

Providing clinicians with reasonable clinical schedules, adequate learning, and collaboration time and encouraging communication through structural supports are necessary but still not sufficient to ensure collaboration. We have specifically structured the operational flow of the clinic to create a transdisciplinary mode of care that reinforces communication.

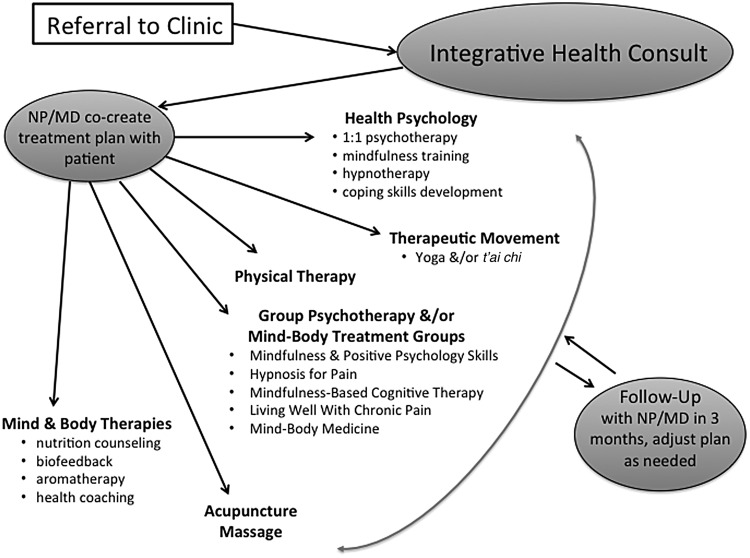

Patients referred to the clinic begin their IH journey with a consult with a NP or physician. As seen in Figure 1, the provider assesses the patient's goals for care, readiness for change, appropriateness for specific integrative therapies, and need for a transdisciplinary approach. Everyone on the medical/nursing team can provide a number of mind–body therapies, typically begun during the intake. The NP or physician guides patients to the appropriate clinicians, allowing for better utilization of their clinicians' time by focusing their efforts on the patients most likely to benefit from their services. Quarterly visits with the NP or physician keep the plan on track. Table 4 notes common considerations we use in clinical decision-making during intake. This approach also allows for patients to see a team of providers that are in frequent communication around their treatment plan. It further serves to allow for peer support for clinicians who are seeing patients who have significant suffering and complexity.

FIG. 1.

Transdisciplinary clinic flow. MD, physician; NP, nurse practitioner.

Table 4.

Clinical Decision-Making Within the Initial Integrative Consult

| Refer to PT when |

| Pain co-occurs with kinesiophobia |

| There are multiple pain sites |

| Myofascial trigger points are present |

| Patient is deconditioned |

| Joints are hypermobile |

| Recommend therapeutic movement (rather than or in addition to PT) when: |

| Patient demonstrates self-motivation |

| Patient is deconditioned without acute pathology |

| Patient has completed PT |

| Patient is in maintenance phase of treatment |

| Refer to acupuncture when patient symptoms: |

| Include pain, digestive issues, and/or fatigue |

| Prevent engagement in movement or psychologic therapy |

| Refer to massage therapy when patients: |

| Have myofascial pain |

| Need support in learning to relax in their body/breath |

| Need to improve their mind–body connection |

| Refer to health psychologist when |

| Medical condition impacts level of function |

| Medical condition impacts quality of life |

| Patient lacks coping skills for self-management of his or her medical condition |

| Patient's relationship to the pain and/or the medical condition is suboptimal |

| Psychologic factors are interfering with patient's ability to effectively cope with symptoms |

| Patient is unable to participate in groups due to acute distress or other individual-level factors |

| Refer to group psychotherapy and/or mind–body treatment groups when patients need |

| Self-regulatory or coping skills |

| Pain education |

| Socialization |

| Note: Avoid referral when patient is suicidal, emotionally unstable, or psychotic |

| Consider mind and body therapies |

| Nutrition counseling |

| Biofeedback |

| Aromatherapy |

| Health coaching |

| Other services with NP/MD/PhD |

NP, nurse practitioner; PT, physical therapy.

All referrals from outside the clinic come to our medical team. If we allowed referrals directly to our integrative providers, each of our providers would be seeing different patients. This would negate the need for and benefit from the collaboration built into our transdisciplinary model. The clinic does allow patients to self-refer to acupuncture, classes, groups, and ongoing health coaching as needed.

Sustainability

Sustaining the IH model should be considered from two perspectives: that of sustaining the clinic itself and that of the patient sustaining the IH model in their own lives. Strong supports for longevity of the clinic itself include both a fiscally sustainable operation, as well as personnel that are well-supported in their own professional and personal growth. For the past 9 years, the operational process has been generating a positive margin, while the personnel continue to thrive. This is not to suggest that there have been no interpersonal challenges, but there is a concerted effort to nurture each individual's growth and an ongoing attempt to align job responsibilities with areas of interest.

From the perspective of individual patients, it is noteworthy that IH supports patients within the context of their current environments, relationships, behaviors, and emotional capacities, while leveraging existing capacities and resources to move patients toward healing.16 Indeed, one of the touted benefits of IH is that once integrative approaches are learned and adopted, they can be utilized repeatedly by patients at little to no cost to self-sustain progress. This is particularly true for a number of the mind–body practices,33 as well as approaches to pain management34 and lifestyle behavior change.35 This prospect alone makes the IH model an attractive avenue for transforming the current acute care model into a successful, empirically-supported model of health improvement and prevention. Moreover, it may be that these IH approaches lower overall cost to society. It has been shown, for example, that mind–body interventions to modulate the impact of stress actually lower health care utilization.5 Given the demand that complex patients suffering from chronic pain can put on the health care system, ongoing support for self-sustained progress would be a relatively minor cost.

Challenges: Access, Staffing, and Training

The clinic faces a number of challenges. Some are common to outpatient academic clinics and some are unique to IH settings.

Access

One of their biggest challenges is providing access to care. The wait time for a first appointment in their clinic is often 6 months. As we look to the future, we are developing partnerships across campus to provide IH outside of their transdisciplinary model to meet the demands of those who do not have complicated chronic pain. For example, a patient with Parkinson's and depression can benefit from a health psychology consult without having an hour-long medical consult first. As for meeting the current demand for the existing model, the clinic is hiring more providers and offering more group classes both in person and through telehealth. As coverage for telehealth grows, the clinic intends to expand this platform to address the needs of its rural and homebound chronic pain population.

Staffing timing

In recent years, the clinic has faced delays and denials for hiring clinicians due to construction interruptions during its expansion and time lags with new position approvals within the medical center. There are also many applicants to the center who are interested in IH but do not have IH experience or training, particularly to treat chronic pain. These factors resulted in positions staying open, sometimes for months or years at a time. The clinic faced challenges to convey the needs of a model that is novel, doesn't prioritize productivity in terms of output, and does not follow typical staffing models used in conventional clinics. In the center, providers room their own patients and take their vitals as indicated; there is one registered nurse for the entire clinic, and there are no licensed practical nurses or medical assistants. As the clinic built relationships across campus and the evidence base for IH has grown, greater dissemination of IH into the larger health care system attracted more interest. For example, the clinic partnered with its health plan and, as mentioned earlier, now provide a series of group yoga sessions specifically for employees with insomnia and chronic low back pain.

Integrative clinician training

There continues to be internal debate about the training required for integrative clinicians. The clinic tends to prioritize experience with integrative approaches, personal practice, and a willingness to practice collaboratively over specific certifications for clinicians. Instead of seeking those who completed a general fellowship, the clinic has sought out clinicians with training in specific IH therapies. The clinic's physical therapists have additional training in myofascial release and neuromuscular manual therapies. The clinic has a NP who is also a massage therapist, a massage therapist trained in health coaching, and a health coach who is also a NP. The clinic does require clinicians to complete a certificate program to deliver clinical mindfulness, yoga therapy, and health coaching. In addition, the health coaches are National Board Certified Health and Wellness Coaches (NBC-HWCs). No one currently working in the clinic is board certified in integrative medicine, in part, because NPs are not eligible to take this examination. The clinic has one nurse who is certified in holistic nursing. The clinic has had one NP who completed the University of Arizona Integrative Medicine Fellowship. As the training options grow, the clinic anticipates hiring people who completed a fellowship program and have board certification. However, the emphasis has been on hiring clinicians who have enough training and expertise to deliver quality IH therapies within the scope of their license. It remains unclear which specific IH therapies those trained through general fellowships will be qualified to deliver.

Conclusion

The background of this clinic, unique provider mix, emphasis on insurance based services, and administrative structure to support transdisciplinary care resulted in a novel model for delivering IH to the clinic's chronic pain population in an academic health care system. As the larger health care system looks for ways to address health crises born of lifestyle and behavior, IH has the potential to provide the theories and framework to evolve the existing system to meet these demands. The authors hope that this article can help others who are working to incorporate IH into conventional patient care. Specifically, the authors present a model that can be replicated across academic medicine and other hospital systems: a model that embodies the values of relationship-centered care, collaboration, and caring for both the patient and the provider. This model represents the clinic's attempt to fulfill its mission.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to dedicate this article to Roy Elam, MD, whose inspiration, vision, and selfless work created the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Vanderbilt, in partnership with Tobi Fishel, PhD. The authors thank Dave Vago, PhD for his comments on an early draft of the article. The authors also thank the tireless team who have delivered this care and made their model possible: Gurjeet Birdee, MD, Inder Broughton, RYT 500, Rickinsha Calbert, Abby Cooper, Andy Coppola, Waverly DeMers, Mark Dempsey, Lindsay Dickson, Jay Groves, MMHC, EdD, Susan Harper, Marni Hillinger, MD, Doug Herr, PsyD, Cindy Hui-Lio, EdD, Michelle Johnson, Leslie Johnston, Taylor Koval, LMT, Melissa Long, RN, Linda Manning, PhD, Sherrie Maxwell, Blaire Morriss, ANP-BC, Michelle Pearce, DMin, MSN, MA, LPC-MHSP, RN, Julie R. Price, PsyD, MSCP, RYT200, Julie Richard, PT, Lori Ryden, Landrew Sevel, PhD, Diane Sussman, Elizabeth Walsh, PhD, Amanda Wentworth, E-RYT 500, CRYT, Kathleen Wolff, APRN, and Chongbin Zhu, PhD.

Author Disclosure Statement

K.A.H., L.C.M., S.D.C., and C.A. declare no competing financial interests. R.Q.W. serves as the Chief Science Advisor for eMindful, Inc.

References

- 1. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dusek JA, Griffin KH, Finch MD, et al. Cost savings from reducing pain through the delivery of integrative medicine program to hospitalized patients. J Altern Complement Med 2018;24:557–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Herman PM, Poindexter BL, Witt CM, Eisenberg DM. Are complementary therapies and integrative care cost-effective? A systematic review of economic evaluations. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Estores IM, Arce L, Hix A, Mramba L, et al. Medication cost savings in inpatient oncology using an Integrative Medicine Model. EXPLORE 2018;14:212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stahl JE, Dossett ML, LaJoie AS, et al. Relaxation response and resiliency training and its effect on Healthcare Resource Utilization. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolever RQ, Dreusicke MH. Integrative health coaching: A behavior skills approach that improves HbA1c and pharmacy claims-derived medication adherence. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2016;4:e000201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain 2012;13:715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. Am Psychol 2014;69:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abrams DI, Dolor R, Roberts R, et al. The BraveNet prospective observational study on integrative medicine treatment approaches for pain. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolever RQ, Goel NS, Roberts RS, et al. Integrative medicine patients have high stress, pain, and psychological symptoms. EXPLORE 2015;11:296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sundberg T, Petzold M, Kohls N, Falkenberg T. Opposite drug prescription and cost trajectories following integrative and conventional care for pain–a case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e96717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi BC, Pak AW. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Invest Med 2006;29:351–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control. U.S. State Prescribing Rates, 2016. Online document at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxstate2016.html, accessed January15, 2019

- 14. Center for Integrative Medicine University of Arizona. What is IM/IH? The University of Arizona: Tucson, Arizona, 2016. Online document at: https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/about/definition.html, accessed January15, 2019

- 15. National Center for Complementary and Intgrative Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What's In a Name? Online document at: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health, accessed January15, 2019

- 16. Witt CM, Chiaramonte D, Berman S, et al. Defining health in a comprehensive context: A new definition of integrative health. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:134–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. What's an NP? Austin, Texas: American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2018. Online document at: https://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/what-is-an-np, accessed January15, 2019

- 18. McCleery E, Christensen V, Peterson K, et al. VA Evidence-based synthesis program reports evidence brief: The Quality of Care Provided by Advanced Practice Nurses. Department of Veterans Affairs (US): Washington, DC, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perloff J, Desroches CM, Buerhaus P. Comparing the cost of care provided to medicare beneficiaries assigned to primary care nurse practitioners and physicians. Health Serv Res 2016;51:1407–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institutes of Health. National Pain Strategy—A Comprehensive Population Health Level Strategy for Pain. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institutes of Health. 2017. Online document at: https://iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHSNational_Pain_Strategy_508C.pdf, accessed January15, 2019

- 21. Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KM. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther 2016;45:5–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Hypnotic approaches for chronic pain management: Clinical implications of recent research findings. Am Psychol 2014;69:167–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: Efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014;69:153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Williams DA. Cognitive—Behavioral therapy in central sensitivity syndromes. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2016;12:2–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 2017;51:199–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:357–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williams DA. Cognitive and behavioral approaches to chronic pain. In: Wallace DJ, Clauw DJ, eds. Fibromyalgia and Other Central Pain Syndromes. Williams & Williams: Philadelphia, PA, 2005:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gittell JH. Rethinking autonomy: Relationships as a source of resilience in a changing healthcare system. Health Serv Res 2016;51:1701–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Havens DS, Gittell JH, Vasey J. Impact of relational coordination on nurse job satisfaction, work engagement and burnout: Achieving the quadruple aim. J Nurs Adm 2018;48:132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Landau DA, Bachner YG, Elishkewitz K, et al. Patients' views on optimal visit length in primary care. J Med Pract Manage 2007;23:12–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin CT, Albertson GA, Schilling LM, et al. Is patients' perception of time spent with the physician a determinant of ambulatory patient satisfaction? Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1437–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Otani K, Kurz RS, Harris LE. Managing primary care using patient satisfaction measures. J Healthc Manag 2005;50:311–324; discussion 324–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith K, Firth K, Smeeding S, et al. Guidelines for creating, implementing, and evaluating mind-body programs in a Military Healthcare Setting. EXPLORE 2016;12:18–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hillinger MG, Wolever RQ, McKernan LC, Elam R. Integrative medicine for the treatment of persistent pain. Prim Care 2017;44: 247–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wolever RQ, Caldwell KL, McKernan LC, Hillinger MG. Integrative medicine strategies for changing health behaviors: Support for primary care. Prim Care 2017;44:229–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]