Mechanisms that integrate the metabolic state of a cell to regulatory pathways are necessary to maintain cellular homeostasis. Endogenous, intrinsically reactive metabolites are capable of forming functional, covalent modifications on proteins without the aid of enzymes1,2, and regulate cellular functions including metabolism3-5 and transcription6. An important ‘sensor’ protein that captures specific metabolic information and transforms it into an appropriate response is KEAP1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1), which contains reactive cysteines that collectively act as an electrophile sensor tuned to respond to reactive species resulting from endogenous and xenobiotic molecules. Covalent modification of KEAP1 results in reduced ubiquitination and the accumulation of the NRF27,8, which then initiates transcription of cytoprotective genes at antioxidant-response element (ARE) loci. Here we have identified a small molecule inhibitor of the glycolytic enzyme PGK1, which reveals a direct link between glycolysis and NRF2 signaling. Inhibition of PGK1 results in accumulation of the reactive metabolite methylglyoxal (MGx), which selectively modifies KEAP1 to form a novel methylimidazole crosslink between proximal cysteine and arginine residues (MICA) posttranslational modification (PTM). This PTM results in KEAP1 dimerization, NRF2 accumulation and activation of the NRF2 transcriptional program. These results demonstrate the existence of direct inter-pathway communication between glycolysis and the KEAP1-NRF2 transcriptional axis, provides new insight into metabolic regulation of cell stress response, and suggests a novel therapeutic strategy for controlling the cytoprotective antioxidant response in numerous human diseases.

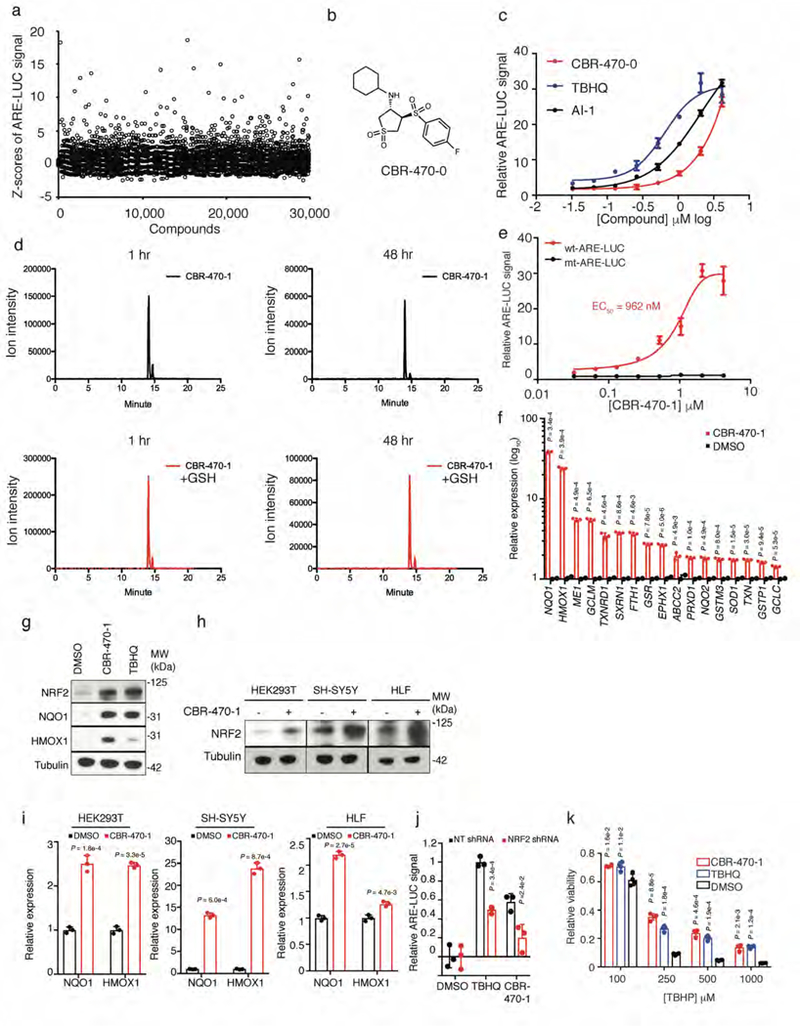

In line with its role in responding to altered cellular conditions, numerous studies have linked deregulated KEAP1-NRF2 signaling in disease, including cancer9, neurodegenerative disorders10, chronic inflammatory diseases11, diabetes12 and aging13. Efforts to therapeutically target NRF2 signaling have largely focused on covalent small molecule agonists of KEAP1, including the clinical candidate bardoxolone methyl (BARD)14. To discover noncovalent modulators of the KEAP1-NRF2 signaling axis, as well as potentially novel mechanisms of action for its regulation, we performed a cell-based, high-throughput phenotypic screen using a NRF2-dependent luciferase reporter (pTI-ARE-LUC) in IMR32 cells15. From a library of diverse heterocyclic compounds, we identified a hit compound, CBR-470-0, that did not contain any obvious electrophilic groups, and induced ARE transcriptional activity to a similar magnitude to the previously reported NRF2 activators tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) and AI-1 (Extended Data Fig. 1a-c). Structure activity relationship (SAR) elaboration around the cyclic sulfone scaffold afforded CBR-470-1 (Fig. 1a), an isobutylamine substituted analog that was not reactive in glutathione assays and had an EC50 ∼1 μM in the cellular ARE-LUC assay (Extended Data Fig. 1d-e). CBR-470-1 treatment resulted in a dose- and time-dependent accumulation of NRF2 protein in IMR32 cells (Fig. 1b), and increased both mRNA and protein levels of the NRF2-responsive genes NQO1 and HMOX1 (Extended Data Fig. 1f-g; Extended Data Table 1). Expression profiling of IMR32 cells exposed to compound for 24 hours revealed that the most significantly enriched gene set was ‘NFE2L2 targets,’ which was comprised of NRF2 target genes (Fig. 1c-d); expression changes of these target transcripts were validated by focused qRT-PCR analysis (Extended Data Fig. 1f). CBR-470-1 also induced transcript levels of NQO1 and HMOX1, as well as enhanced NRF2 protein stabilization in HEK293T, SH-SY5Y, and primary human lung fibroblasts (HLF; Extended Data Fig. 1h-i), indicating that these effects are not restricted to a specific cell type. Genetic depletion of NRF2 protein using shRNA inhibited the ability of CBR-470-1 and TBHQ to induce luciferase expression, indicating that CBR-470-1 activity is dependent upon NRF2 (Extended Data Fig. 1j). Finally, CBR-470-1 treatment induced a cytoprotective NRF2 phenotype in vitro, as shown by protection of SH-SY5Y cells challenged with the cell permeable peroxide TBHP (Extended Data Fig. 1k).

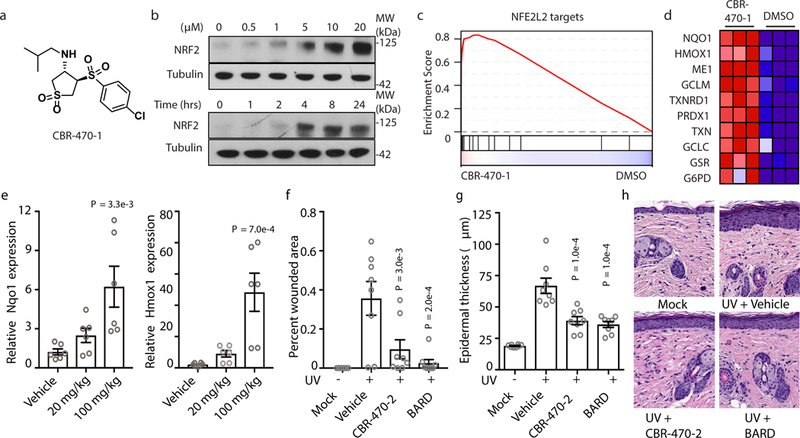

Fig. 1|. CBR-470-series compounds activate NRF2 signaling in vitro and in vivo.

a, Structure of CBR-470-1. b, NRF2 protein levels from IMR32 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of CBR-470-1 for 4 hours (top) or 5 μM CBR-470-1 for the indicated time periods (bottom). Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments. c, GSEA enrichment plot depicting the enrichment of a NRF2 target gene set (“Singh_NFE2L2_Targets” in MSigDB) from IMR32 cells treated for 24 hours with 5 μM CBR-470-1 (n=3, P < 0.0001, nom. p-value in GSEA). d, Heat map representation of the leading-edge subset of the most upregulated NRF2-regulated transcripts upon CBR-470-1 treatment. Data are biologically independent samples. e, Relative Nqo1 and Hmox1 transcript levels 24 hr after indicated P.O. doses of CBR-470-2 (n=6, biologically independent samples). f, Quantification of wounded area by automated image analysis from animals of the indicated treatment groups at study end (day 10). g, Quantification of epidermal thickness from H&E stained sections from the indicated groups at study end. h, Representative images of H&E stained skin sections from animals sacrificed at day 10 of the study. CBR-470-2, 50 mg/kg BID PO; BARD, bardoxolone methyl, 3mg/kg BID PO; UV, 200 mJ/cm2; data are mean and s.e.m., n=8 animals. Statistical analyses are one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction (e-g). Data are mean and s.e.m.

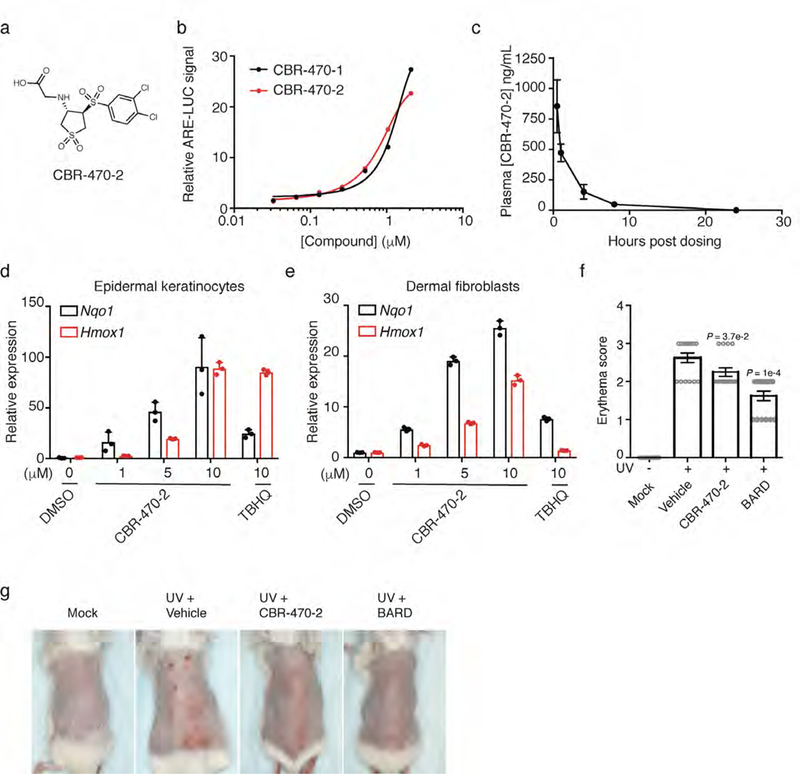

We next sought to determine whether CBR-470-1 or related analogs induce activation of NRF2 signaling in vivo. Oral dosing of Balb/C mice with 50 mg/kg (BID, P.O.) of a glycine-substituted analog, CBR-470-2, which is equally potent to CBR-470-1 and has more favorable bioavailability (Extended Data Fig. 2a-e), induced NRF2 target gene expression in several organs, with dose-dependent increases in Nqo1 and Hmox1 transcript levels observed in the skin (Fig. 1e). Published studies in NRF2-knockout mice have demonstrated that NRF2 is essential to protect against photo-aging phenotypes and skin carcinogenesis16 resulting from UV irradiation17. We therefore evaluated the activity CBR-470-2 in this acute UV damage mouse model. Mice were prophylactically dosed with CBR-470-2 or BARD (3 mg/kg, P.O.) for five days before exposure to a single dose of UV irradiation. Mice were then dosed for an additional five days, sacrificed and UV damage was quantified. CBR-470-2 and BARD treatment resulted in comparable beneficial effects on erythema histological scores and total wounded area (Fig. 1f; Extended Data Fig. 2f-g). Both CBR-470-2 and BARD were also found to decrease epidermal thickness in response to UV exposure, consistent with activation of the NRF2 cytoprotective program (Fig. 1g-h)18. The combined pharmacodynamic and efficacy data indicate that CBR-470-2 treatment is capable of modulating NRF2 signaling in vivo, despite this compound series operating via an apparent mechanism that is independent of direct KEAP1 binding.

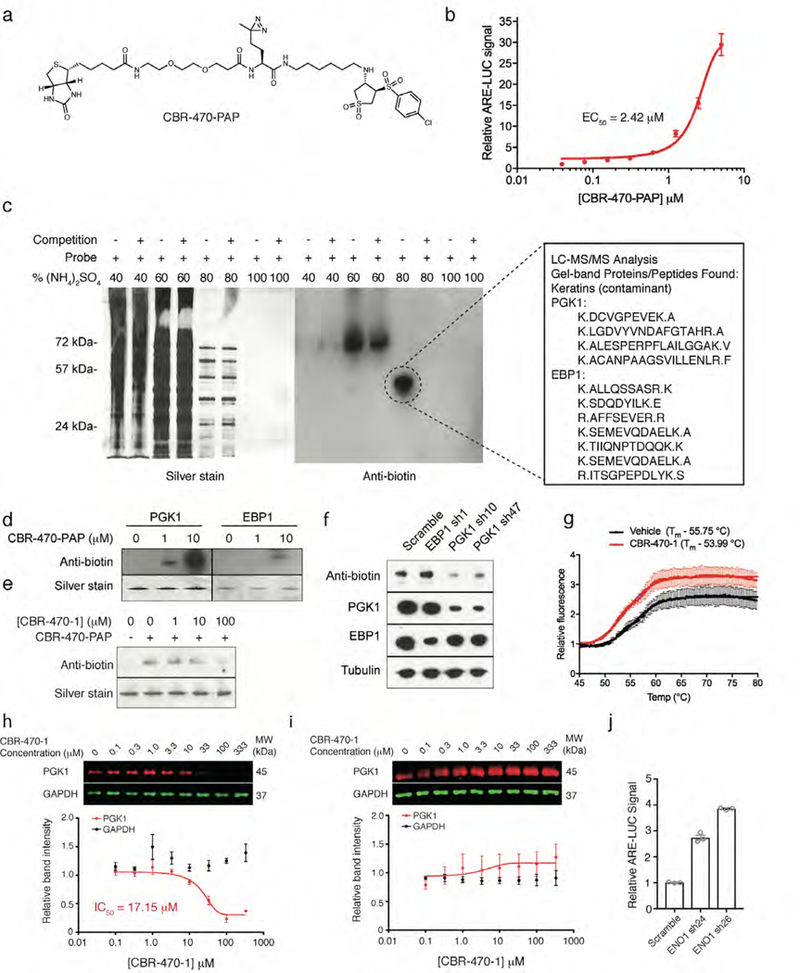

To determine the mechanism by which CBR-470-1 activates NRF2 signaling, we generated a photo-affinity probe containing biotin and diazirine substituents, termed CBR-470-PAP, which retained cellular activity in ARE-LUC reporter assays (EC50 = 2.4 μM, Extended Data Fig. 3a-b). Treatment of IMR32 cells with 5 μM CBR-470-PAP for 1 hr, followed by UV irradiation and subsequent anti-biotin Western blot analysis of cellular lysates (Fig. 2a), together with biochemical fractionation and LC-MS/MS analysis, identified the enzyme phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) as a potential target of CBR-470-PAP (Extended Data Fig. 3c). In vitro binding experiments with recombinant protein revealed that CBR-470-PAP selectively labeled PGK1, which was blocked with CBR-470-1 soluble competitor, or shRNA depletion of PGK1 protein levels (Extended Data Fig. 3d-f). Thermal stability assays in the presence of CBR-470-1 resulted in a consistent shift in PGK1 stability, and isothermal dose response profiling19 against PGK1 and GAPDH also confirmed the selective, dose-dependent alteration of PGK1 stability in the presence of CBR-470-1 (Extended Data Fig. 3g-i). Furthermore, transient and viral shRNA knockdown of PGK1 in IMR32 cells activated ARE-LUC reporter signal and expression of NQO1 (Fig. 2b-c). Knockdown or overexpression of PGK1 protein modulated the NRF2-reporter, with decreased and increased observed CBR-470-1 EC50 values, respectively (Fig. 2d-e). Finally, depletion of enolase 1, an enzyme downstream of PGK1, was also found to induce ARE-LUC signal in IMR32 cells (Extended Data Fig. 3j). These results suggested that CBR-470-1 modulation of PGK1 activity, and therefore glycolysis, regulates NRF2 activation.

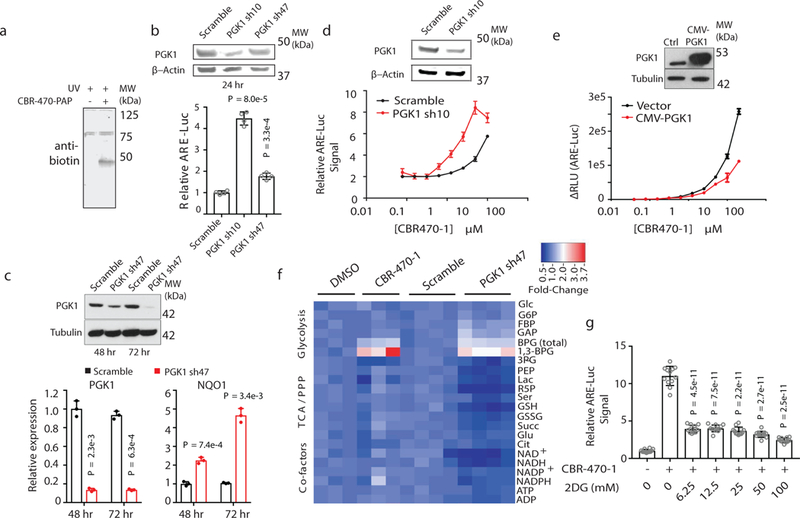

Fig. 2.|. CBR-470-1-dependent inhibition of glycolysis activates NRF2 signaling.

a, Anti-biotin Western blot analysis of IMR32 cells treated with CBR-470-PAP (10 μM) for one hour and exposed to UV light to induce photocrosslinking (representative shown from n = 4 biological replicates). b, Transient transfection of shRNA constructs targeting PGK1 in HEK293T cells activates the ARE-LUC reporter. PGK1 and β-actin protein levels shown from representative experiments (n=4 biological replicates). c, Viral shRNA knockdown of PGK1 induces NQO1 mRNA levels in IMR32 cells. PGK1 and Tubulin protein levels are shown from representative experiments (n=3). d,e, CBR-470-1 activation of ARE-LUC reporter in HEK293T cells with transient knockdown (d) or overexpression (e) of PGK1 demonstrates opposing effects on compound potency. PGK1, Actin and Tubulin protein levels are shown from representative experiments (n=3). f, Heat map depiction of relative metabolite levels in IMR32 cells treated for 30 min with CBR-470-1 (left) or viral shRNA knockdown of PGK1 (right) relative to DMSO and scramble shRNA controls, respectively. BPG refers to both 2,3-BPG and 1,3-BPG, whereas 1,3-BPG specifically refers to the 1,3-isomer. g, ARE-LUC reporter activity in IMR32 cells co-treated with CBR-470-1 (5 μM) and 2DG for 24 hr. (n=12). Statistical analyses are univariate two-sided t-tests (b, c, g). Data are mean and s.d. of biologically independent samples.

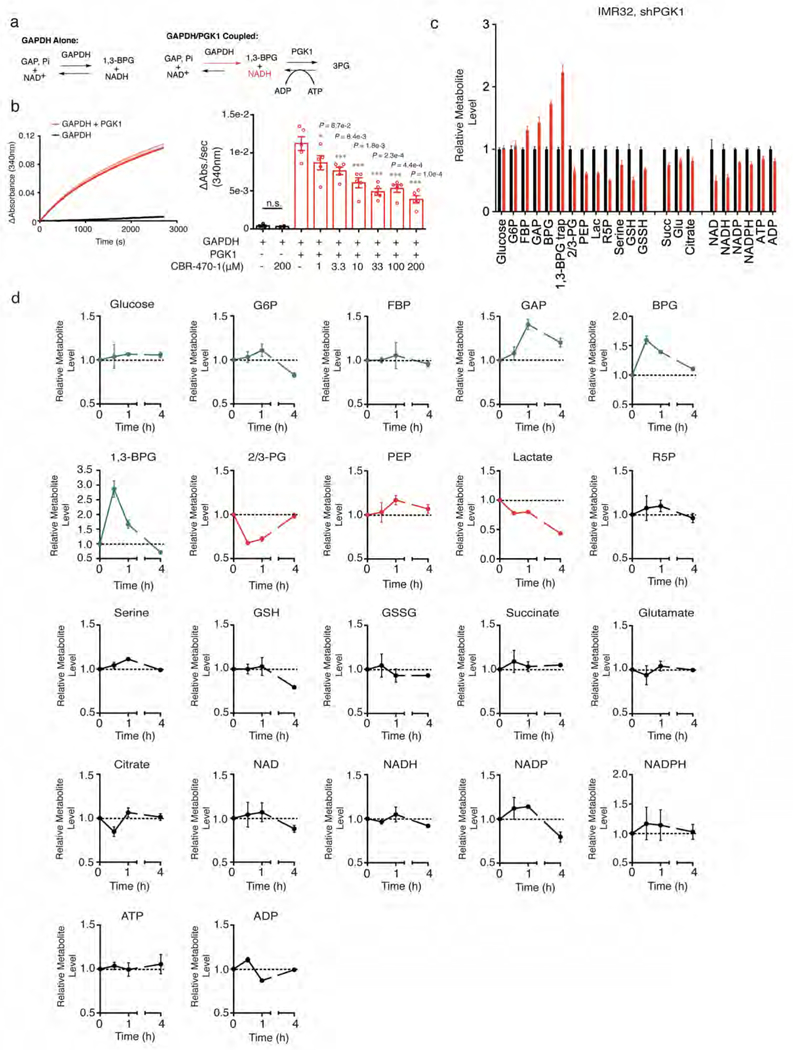

Consistent with the PGK1 inhibitory activity of CBR-470-1 (Extended Data Fig. 4a-b), targeted metabolomic profiling4,20 of IMR32 cells treated with compound revealed a rapid increase in metabolite levels upstream of PGK1 (1,3- and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate [BPG], and D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate [GAP]), and depletion of downstream metabolites such as 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) and lactate (Lac), which mirrored the profile observed upon viral knockdown of PGK1 in IMR32 cells (Fig. 2f; Extended Data Fig. 4c-d; Extended Data Table 2). In addition, co-treatment of ARE-LUC expressing reporter cells with CBR-470-1 and an inhibitor of glucose entry into glycolysis, 2-deoxyglucose (2DG), significantly blunted reporter activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2g). Taken together, these data suggested that glycolytic intermediates may serve as a signal to the NRF2 signaling axis.

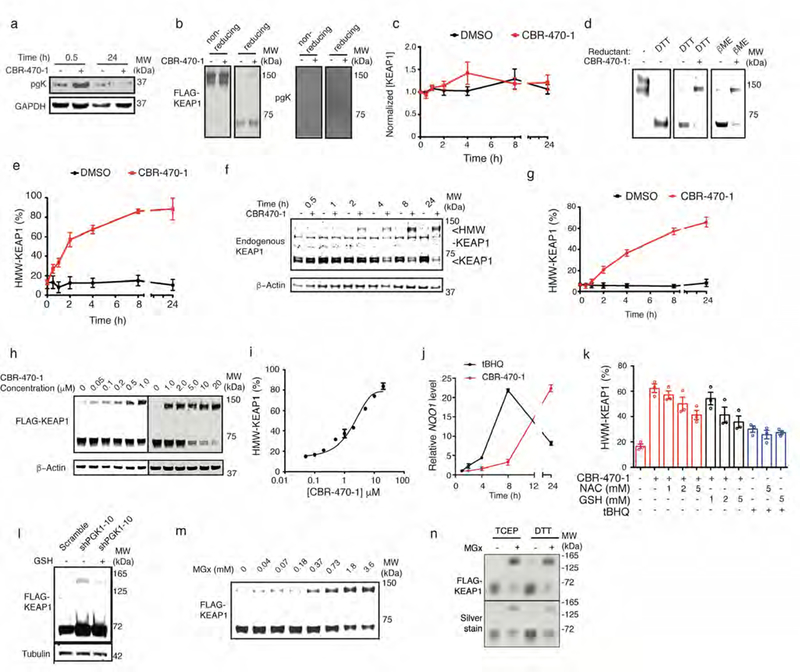

We first investigated if 1,3-BPG, which is directly metabolized by PGK1, could be involved in signaling to the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway via phosphoglyceryl-lysine (pgK) modification of KEAP1. However, CBR-470-1 treatment of IMR32 cells for 30 minutes, a time at which 1,3-BPG levels are elevated, did not result in altered KEAP1 levels, or any α-pgK immunoreactive bands using polyclonal antibodies raised against the phosphoglyceryl-lysine epitope (Extended Data Fig. 5a-c). These Western blots did, however, reveal the appearance of a CBR-470-1-dose-dependent, high molecular weight KEAP1 (HMW-KEAP1) band at roughly twice the molecular weight of monomeric KEAP1 (Fig. 3a). The HMW-KEAP1 band was stable to reduction (Extended Data Fig. 5d) and exhibited kinetics and dose-dependent formation consistent with CBR-470-1-dependent NRF2 stabilization and NQO1 induction (Fig. 1b), but distinct from the direct KEAP1 alkylator tBHQ (Extended Data Fig. 5e-j). Co-treatment of cells with CBR-470-1 and either reduced glutathione (GSH) or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) inhibited HMW-KEAP1 band formation (Extended Data Fig. 5k). Knockdown of PGK1, which activates NRF2 target gene expression, also formed HMW-KEAP1, and this band was competed by co-treatment with GSH (Extended Data Fig. 5l). Together these data indicated that modulation of glycolysis by CBR-470-1 results in the formation of a HMW-KEAP1 that is consistent with a covalent KEAP1 dimer, which has been previously observed21-23, but remained uncharacterized at the molecular level.

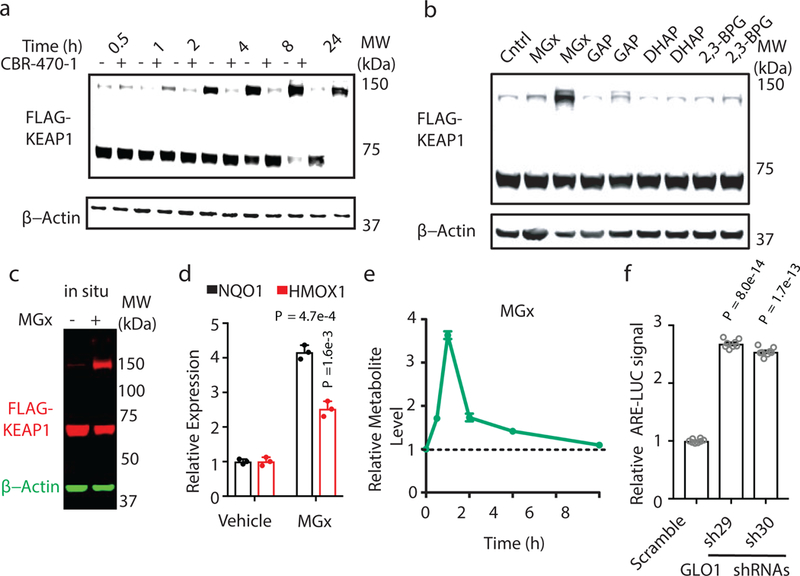

Fig. 3.|. Methylglyoxal modifies KEAP1 to form a covalent, high molecular weight dimer and activate NRF2 signaling.

a, Time-course, anti-FLAG Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates from HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-KEAP1 treated with DMSO or CBR-470-1. b, Western blot monitoring of FLAG-KEAP1 migration in HEK293T lysates after incubation with central glycolytic metabolites in vitro (1 and 5 mM, left and right for each metabolite). c, FLAG-KEAP1 (red) and β-actin (green) from HEK293T cells treated with MGx (5 mM) for 8 hr. d, Relative NQO1 and HMOX1 mRNA levels in IMR32 cells treated with MGx (1 mM) or water control (n=3). e, LC-MS/MS quantitation of cellular MGx levels in IMR32 cells treated with CBR-470-1 relative to DMSO (n=4). f, ARE-LUC reporter activity in HEK293T cells with transient shRNA knockdown of GLO1 (n=8). Univariate two-sided t-test (d, f); data are mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

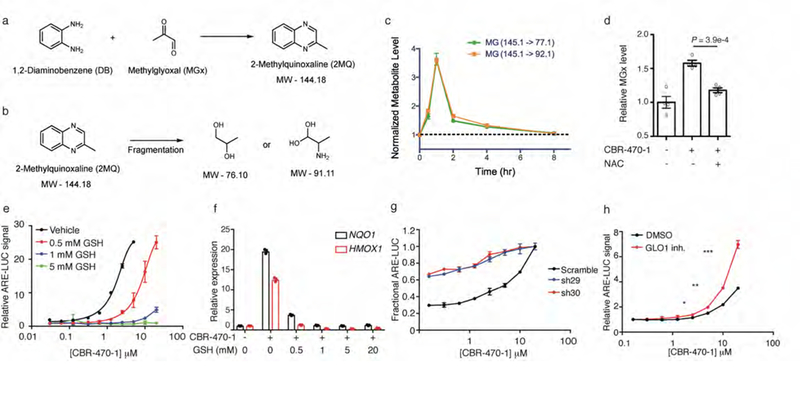

Several central glycolytic metabolites other than 1,3-BPG contain reactive functionalities, including the triosephosphate isomers D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), as well as their non-enzymatic elimination product methylglyoxal (MGx), an electrophilic dicarbonyl compound that has been found to form numerous modifications on nucleophilic residues in proteins24,25. Among these candidates, only treatment of cell lysates or live cells with MGx resulted in the selective formation of HMW-KEAP1 (Fig. 3b-c). Treatment of FLAG-KEAP1 containing lysates or purified KEAP1 with freshly distilled MGx induced dose-dependent formation of HMW-KEAP1 at mid-μM concentrations (Extended Data Fig. 5m-n), which is consistent with the range of MGx concentrations previously reported in living cells26,27. MGx treatment in cells functionally activated expression of the downstream NRF2 target genes NQO1 and HMOX1 (Fig. 3d). Targeted LC-MS measurement of derivatized methylglyoxal confirmed that CBR-470-1 treatment resulted in significant elevation of cellular MGx levels in the first few hours of treatment (Fig. 3e; Extended Data Fig. 6a-c), which was sensitive to GSH treatment (Extended Data Fig. 6d-f). To further test the involvement of MGx in KEAP1-NRF2 signaling, we perturbed its degradation, which is mediated by GSH and glyoxylase 1 (GLO1). Knockdown of GLO1 by shRNA resulted in ARE-LUC reporter activation (Fig. 3f), and also sensitized cells to CBR-470-1 activation of the ARE-LUC reporter (Extended Data Fig. 6g). Direct modulation of GLO1 enzymatic activity with a cell-permeable inhibitor (GLOi) also amplified reporter activation by CBR-470-1 (Extended Data Fig. 6h). Collectively, these metabolomic, proteomic and transcriptomic data established shared kinetics between MGx accumulation, HMW-KEAP1 formation and NRF2 pathway activation, suggesting the existence of a direct link between glycolysis and the KEAP1-NRF2 signaling pathway mediated by the direct modification of KEAP1 by MGx.

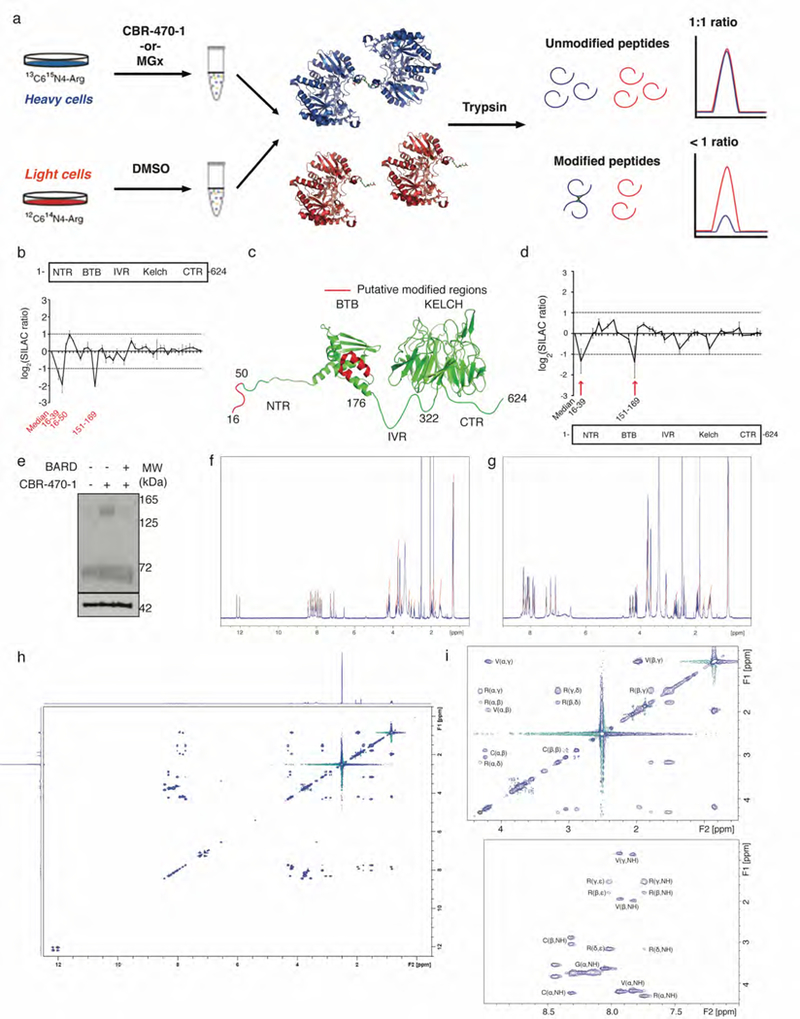

A SILAC-based quantitative proteomic approach (Extended Data Fig. 7a) suggested the NTR (N-terminal region, amino acids 1-50) and BTB domains (amino acids 150-169) as candidate domains and residues that could be involved in HMW-KEAP1 formation in response to CBR-470-1-induced MGx elevation (Extended Data Figure 7b-d). We therefore examined more than a dozen C-to-S, K-to-M/R, and R-to-A mutations within these domains, as well as other known functional residues in KEAP1, for their effect on HMW-KEAP1 formation. Two arginine residues (R15 of the NTR domain and R135 of the BTB domain) significantly, but incompletely, reduced the formation of HMW-KEAP1 (Fig. 4a). More striking was the near complete inhibition of HMW-KEAP1 formation of the C151S mutant in the BTB domain (Fig. 4a). Consistent with this effect, C151-containing tryptic peptide levels were reduced by MGx treatment, and pre-treatment of cells with bardoxolone methyl, which alkylates C151, inhibited HMW-KEAP1 formation (Extended Data Fig. 7d-e). C151 lies in an exposed region of the BTB domain that is predicted to mediate the homodimeric interface between two KEAP1 monomers, which is necessary for proper NRF2 binding and ubiquitination8,23. Therefore, the strong abrogation of HMW-KEAP1 formation through mutation of C151 and proximal arginines suggested that MGx may be mediating an uncharacterized modification between these residues.

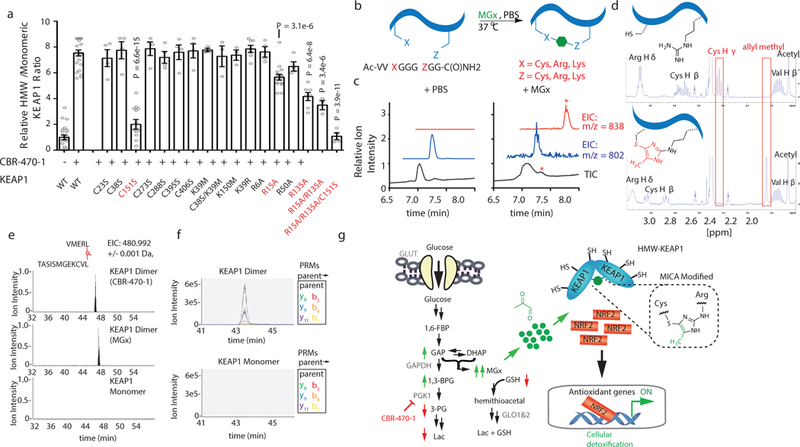

Fig. 4.|. Methylglyoxal forms a novel posttranslational modification between proximal cysteine and arginine residues in KEAP1.

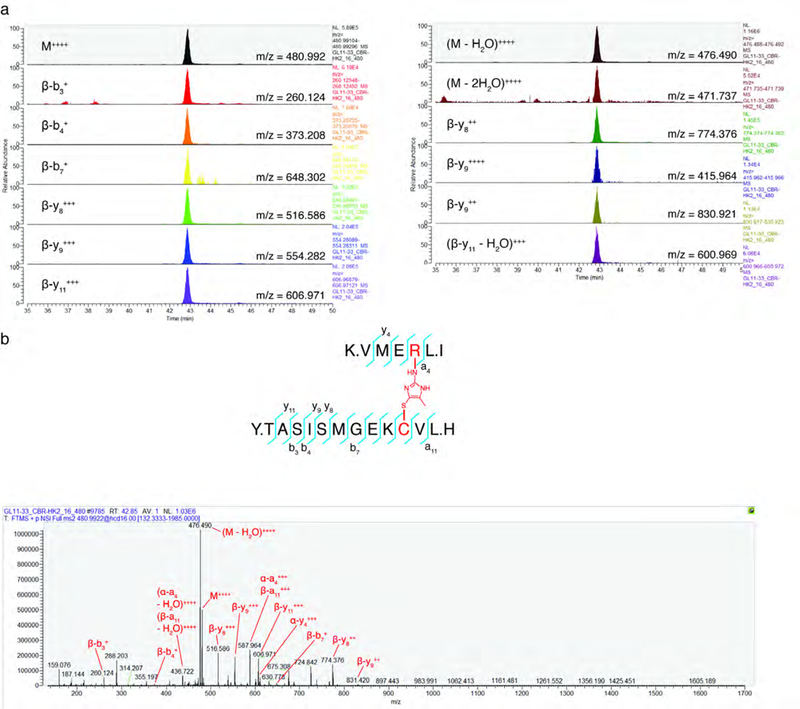

a, Quantified HMW-KEAP1 formation of wild-type or mutant FLAG-KEAP1 from HEK293T cells treated with DMSO or CBR-470-1 for 8 hr (n=23 for WT; n=16 for R15A; n=13 for C151S; n=7 for K39R, R135A; n=4 for R6A, R50A, all other C-to-S mutations, and R15/135A & C151S triple-mutant; n=3 for R15/135A, and all K-to-M mutations). b, Schematic of the model peptide screen for intramolecular modifications formed by MGx and nucleophilic residues. c, Total ion- (TIC) and extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) from MGx- and mock-treated peptide, with a new peak in the former condition marked with an asterisk. EICs are specific to the indicated m/z. (n=3 independent biological replicates). d, 1H-NMR spectra of the unmodified (top) and MICA-modified (bottom) model peptide, with pertinent protons highlighted in each. Notable changes in the MICA-modified spectrum include the appearance of a singlet at 2.04 p.p.m. (allyl methyl in MICA), loss of the thiol proton at 2.43 p.p.m., and changes in chemical shift and splitting pattern of the cysteine beta protons and the arginine delta and epsilon protons. Full spectra and additional multidimensional NMR spectra can be found in Extended Data Fig. 7. e, EIC from LC-MS/MS analyses of gel-isolated and digested HMW-KEAP1 (CBR-470-1 and MGx-induced) and monomeric KEAP1 for the C151-R135 crosslinked peptide. Slight retention time variation was observed on commercial columns (n=3 independent biological replicates). f, PRM chromatograms for the parent and six parent-to-daughter transitions in representative targeted proteomic runs from HMW-KEAP1 and monomeric digests (n=6). g, Schematic depicting the direct communication between glucose metabolism and KEAP1-NRF2 signaling mediated by MGx modification of KEAP1 and subsequent activation of the NRF2 transcriptional program. Univariate two-sided t-test (a); data are mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

In an effort to identify this modification, we synthesized a model peptide containing cysteine and arginine separated by a glycine linker, which was intended to mimic high inter- or intramolecular Cys/Arg proximity, and treated it with MGx at physiologic temperature and pH overnight (Fig. 4b). LC-MS analysis revealed a new peak, which corresponded to a mass increase of 36 Da, consistent with a mercaptomethylimidazole crosslink (Fig. 4c-d) formed by nucleophilic attack of the dicarbonyl by the side chains of cysteine and arginine, followed by dehydration-mediated cyclization and formation of a novel methylimidazole (MICA) posttranslational modification. We purified this product and confirmed its structure by a series of one- and two-dimensional NMR experiments (Fig. 4d; Extended Data Fig. 7f-i). To determine whether MICA modification occurs within KEAP1 protein, we treated cells with CBR-470-1 or MGx, isolated HMW-KEAP1 and monomeric KEAP1 by gel, and then digested these discrete populations for LC-MS/MS analyses. A peptide bearing a MICA crosslink between C151 and R135 was identified in isolated HMW-KEAP1 from both CBR-470-1 and MGx treatment, but not in the isolated monomeric KEAP1 (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, parallel-reaction monitoring (PRM) confirmed the presence and co-elution of more than a dozen parent-to-daughter ion transitions that were uniquely present in HMW-KEAP1 (Fig. 4f; Extended Data Fig. 8a-b). These studies suggest a model where glycolytic metabolic status is coupled to NRF2-dependent gene expression through the direct interaction of a reactive glycolytic metabolite, MGx, and the sentinel protein KEAP1 via the formation of a stable and mechanistically novel protein PTM (Fig. 4g).

While it has been reported that MGx can form covalent modifications on diverse proteins, the compositions, sites and functions of these modifications have remained enigmatic. Likewise, several recent reports have implicated MGx in the pathogenesis of diseases such as diabetes28 and aging29, yet the discrete molecular targets of MGx in these contexts are unknown. Here we found that inhibition of PGK1 increases triosephosphate levels, which results in elevated levels of cellular MGx and the formation of a HMW-KEAP1 species leading to NRF2-dependent gene expression. Formation of the HMW-KEAP1 species involves a novel PTM, MICA, that is dependent on MGx and serves to form a covalent linkage between proximal cysteine and arginine residues. These results raise intriguing questions about the general reactivity of MGx, its potential role as a signaling metabolite in other cellular processes, and the specific modifications involved in oft-cited advanced glycated endproducts as biomarkers of disease pathology. In our studies both cellular and lysate treatment with MGx showed selective modification of C151 in KEAP1, likely due to the intrinsic hyperreactivity of this residue, and the presence of properly oriented arginine(s) that enables formation of the MICA modification. Additional factors such local metabolite concentration gradients may also contribute to MICA formation in KEAP1. Future studies to elucidate the full target profile of MGx, and specifically other inter- and intramolecular MICA modifications, are expected to shed light on this model and provide a global view of MGx modification sites in the proteome.

The direct connection between glucose metabolism and the KEAP1-NRF2 axis by MGx adds an additional layer of regulation to both pathways and global metabolic status. First, this connection highlights the role of glycolysis in regulating cellular redox status beyond the contribution to NADPH and glutathione production. These reducing equivalents are critical for the regulation of a wide range of reactive species in the cell, and when these levels are deregulated, the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway is poised to respond and limit cellular damage. Recent studies have also implicated the output of NRF2 transcriptional program in the direct detoxification of MGx through increased glutathione synthesis30, GLO1 transcription, as well as redirection of glucose carbon away from central metabolites (e.g. MGx) and into the pentose phosphate pathway31. Therefore, the direct coupling of glucose metabolism with KEAP1 function through MGx creates an intrinsic feedback loop to sense and respond to changing metabolic demands in the cell. A final aspect of this study is the notion that modulation of endogenous reactive metabolite levels using small molecules may represent an alternative approach toward activating the ARE pathway for treatment of a number of disease involving metabolic stress.

Methods

Chemicals.

TBHQ, 2DG, MGx and GSH were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. The synthesis of AI-1 has been described previously32. The GLO1 inhibitor (CAS No. 174568-92-4) was from MedChemExpress. CBR-470-0 and CBR-581-9 were from ChemDiv. CBR-470-1 (initially from ChemDiv as D470-2172) and related analogs were synthesized in house according to full methods described in the Supplementary Information. All commercially obtained chemicals were dissolved in DMSO and used without further purification with the exception of 2DG, MGx and GSH, which were delivered as aqueous solutions.

Cell Culture.

IMR32, SH-SY5Y, HeLa, and HEK293T cell lines were purchased from ATCC. Human lung fibroblasts (HLF) and mouse dermal fibroblasts (MDFs, C57BL/6-derived) were obtained from Sciencell and used before passage 3. IMR32, HLF, SH-SY5Y, HeLa, and HEK293T cells were propagated in DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning) and Anti-anti (Gibco). MDFs were propagated in fibroblast medium 2 from Sciencell. Mouse epidermal keratinocytes (MPEK-BL6) were obtained from Zen Bio and propagated in epidermal keratinocyte medium (Zen Bio).

High throughput screening and ARE-LUC reporter assay.

For high throughput screening, IMR32 cells were plated at 5 × 103 cells per well in white 384-well plates in 40 μL of growth medium. The next day 100 ng of pTI-ARE-LUC reporter plasmid in 10 μL of Optimem medium (Gibco) was transfected into each well using Fugene HD at a dilution of 1 μg plasmid DNA: 4 μL of Fugene. 24 hours later, compounds were transferred using a 100 nL pintool head affixed to PerkinElmer FX instrument such that the final screening concentration was 2 μM. After 24 hour incubation, ARE-LUC luminance values were recorded on an Envision instrument after the addition of 30 μL of Bright Glo reagent solution (Promega, diluted 1:3 in water). Compounds which increased ARE-LUC signal greater than 4 Z-scores from plate mean were deemed hits. For overexpression and knockdown experiments in HEK293T with ARE-LUC reporter readouts, 5 × 105 cells were plated on poly-d-lysine coated plates and transfected with 1.5 μg of overexpression or shRNA plasmid and 500 ng of pTI-ARE-LUC using Optimem medium and Fugene in the same mode as above. 24 hours later, 103 transfected cells were plated in 50 μL of growth medium in white 96-well plates. After a 24 hour incubation, an additional 50 μL of growth medium with compound at the indicated concentrated was added to each well. ARE-LUC luminance values were recorded on an Envision plate reader 24 hours later by the addition of 75 μL of Bright Glo reagent solution (1:3 in water).

Peroxide stress model.

104 SH-SY5Y cells were plated in 100 μL of growth medium in white 96-well plates. After 48 hours of compound treatment, 20 μL of tert-butyl peroxide diluted to the indicated concentrations was added to each well. After an 8 hour incubation, cell viability measurements were recorded on an Envision plate reader after the addition of 50 μL of a Cell Titer Glo solution (Promega, diluted 1:6 in water). Relative viabilities are reported as a fraction relative to the same dose of compound treatment without TBHP.

shRNA knockdown studies.

PGK1-targeting shRNA vectors sh10 and sh47 refer to Sigma Mission shRNA lentiviral clones NM_000291.2-338s1c1 and NM_000291.2-935s1c1 respectively. GLO1-targeting shRNA vectors sh29 and sh30 refer to Sigma Mission shRNA lentiviral clones NM_006708.1-195s1c1 and NM_006708.1-292s1c1 respectively. The non-targeting scrambled control vector refers to SHC002 (Sigma). Lentiviruses were generated in HEK293T cells by transient expression of the above vectors with pSPAX2 and pMD2.G packaging vectors (Addgene plasmids 11260 and 12259). Viral supernatants were collected after 48 hours of expression and passed through a 70 μm syringe filter before exposure to target cells.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Cells were collected by trypsinization and subsequent centrifugation at 500g. RNA was isolated using RNeasy kits from Qiagen and concentrations obtained using a NanoDrop instrument. 500ng-5μg of RNA was then reverse transcribed with oligo dT DNA primers using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis kit from Invitrogen. Quantitative RT-PCR reactions were measured on a Viia 7 Real-Time PCR system (Thermo) using a Clontech SYBR green-based master mix. Gene specific primer sets are provided in Extended Data Table 1. Reactions were normalized to TUBG1 levels for each biological replicate and relative transcript abundance calculated using the comparative Ct method.

Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA).

Total RNA was extracted from IMR32 cells treated for 24 hours with either DMSO or 5 μM CBR-470-1 (3 biological replicates per condition) using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA-seq experiments were performed by the Scripps Next Generation Sequencing Core according to established in house methods. Gene set enrichment analyses and leading edge heatmaps were generated with TPM values from the above experiment using the java GSEA package. “NFE2L2 targets” gene set refers to Molecular Signature Database (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb) gene set ID M2662.

Quantitative Metabolomic Profiling.

For polar metabolite profiling experiments, cells were grown in 15 cm plates and cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% P/S prior to media replacement containing either vehicle (DMSO) or the indicated dose of CBR-470-1. Following incubation for the appropriate time, cells were scraped into ice-cold PBS and isolated by centrifugation at 1,400g at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 300 μl of an 80:20 mixture of cold MeOH/H2O, an internal standard was added (10 nmol d3-serine; Sigma Aldrich), and the suspension was sonicated (Fisher Scientific FB-505) for 5 seconds followed by a 10 minute centrifugation at 16,000g. The supernatant was collected, dried under N2 gas and resulting dried metabolites resuspended in 30 μl of 40% MeOH/H2O for analysis on an Agilent triple quadrupole LC-MS/MS (Agilent Technologies 6460 QQQ). For negative mode operation, metabolites were separated by hydrophilic interaction chromatography with a Luna-NH2 column (Phenomenex) running mobile phase A (CH3CN supplemented with 0.2% NH4OH) and B (95:5 v/v H2O:CH3CN supplemented with 50 mM NH4OAc and 0.2% NH4OH) and the following gradient: 0% B for 3 min; linear increase to 100% B for 27 min at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min, followed by an isocratic flow of 100% B for 3 min. The spectrometer settings were: capillary voltage = 4.0 kV, drying gas temperature = 350°C at 10 L/min, and the nebulizer pressure was 45 psi. Metabolite peak transitions and retention times are listed in Extended Data Table 2 and were confirmed by running standards for measured glycolytic, PPP, CAC and co-factor metabolites. 2-phosphoglycerate and 3-phosphoglycerate isomers were quantified in aggregate (2PG/3PG). Relative metabolite abundance was quantified by integrated peak area for the given MRM-transition, and all metabolite levels were normalized to internal standard extracted ion intensity values for d3-serine. These parameters were used to quantify all metabolites, with the exception of 1,3-BPG and MGx, which required chemical derivitization to stable intermediates prior to LC-MS/MS quantification, as previously reported20,33. MGx deviated from all other metabolites, as it was separated on a Gemini reverse-phase C18 column (5 mm, 4.6 mm x 50 mm; Phenomenex) together with a pre-column (C18, 3.5 mm, 2 mm x 20 mm) and detected in positive mode analysis, with mobile phase A (H2O) and B (50:50 v/v H2O:CH3CN) supplemented with 0.1% TFA. The gradient started with 0% B for 2 min and increased linearly to 100% B over 10 min with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min, followed by an isocratic gradient of 100% B for 5 min at 0.4 ml/min. The QQQ settings were the same as above.

FLAG-tagged Protein Expression and Western Blotting.

Full-length, human PGK1 (NM_000291, Origene) transiently expressed from a pCMV6 entry vector with a C-terminal Myc-DDK tag; full-length, human KEAP1 (28023, Addgene) was transiently expressed from a pcDNA/FRT/TO plasmid with a C-terminal 3xFLAG tag. All references to FLAG-PGK1 or FLAG-KEAP1 represent the proteins in the aforementioned vectors, respectively. Transient protein expression was performed in confluent 10 cm plates of HEK293T cells by transfection of 1 μg plasmid with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For in situ compound or metabolite treatment experiments, compounds were added approximately 24 hours after transfection, and incubated for the indicated duration. For FLAG-KEAP1 western blotting and immunoprecipitation experiments, cells were harvested by scraping, pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with PBS and lysed in 8 M urea, 50 mM NH4HCO3, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich), and EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor (Roche), pH 8.0, at 4 ˚C. Lysate was sonicated (Fisher Scientific FB-505), insoluble debris cleared by centrifugation, and the supernatant was diluted into 4X Laemmli buffer containing 50mM dithiothreitol (DTT) as a reducing agent. Samples were prepared for SDS-PAGE by heating to 95 ˚C for 5 minutes, cooled to room temperature, resolved on NuPAGE Novex 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Invitrogen), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes by standard western blotting methods. Membranes were blocked in 2% BSA in TBS containing 0.1% tween-20 (TBST) and probed with primary and secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies used in this study include: anti-FLAG-M2 (1:1000, F1804, Sigma Aldrich), anti-KEAP1 (1:500, SC-15246, Santa Cruz), anti-HSPA1A (1:1000, 4872, Cell Signaling), anti-ACTB (1:1000, 4790, Cell Signaling), anti-GAPDH (1:1000, 2118S, Cell Signaling) and TUBG (1:1000, 5886, Cell Signaling). Rabbit polyclonal anti-pgK antibody was generated using pgK-modified KLH and affinity purification as described4 at a 1:400 dilution of a 0.33 mg/mL stock in 10mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.5), 150mM NaCl, 30% glycerol and 0.02% sodium azide. Secondary donkey anti-rabbit, donkey anti-goat, and donkey anti-mouse (Licor), were used at 1:10,000 dilution in 2% BSA-containing TBST and incubated for 1 hour prior to washing and imaging on a Licor infrared scanner. Densitometry measurements were performed with ImageJ software.

Time- and dose-dependent CBR-470-1 treatment studies were performed in HEK293T cells 24 hours after transient transfection of FLAG-KEAP1, or in IMR32 cells for endogenous KEAP1. Fresh RPMI media with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% P/S and the indicated concentration of CBR470-1 (20 μM for time-dependent experiments) or equivalent DMSO was added to cells in 10 cm dishes. Following the indicated incubation time cells were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X 100, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich), and EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor (Roche), pH 7.4] and processed for western blot as indicated above.

Target identification studies with CBR-470-PAP.

10 cm dishes of confluent IMR32 cells were exposed to 5 μM CBR-470-PAP with the addition of either DMSO or a 50-fold molar excess of CBR-470-1 (250 μM) for 1 hour at 37 °C. Samples were then UV crosslinked using a Stratalinker 2400 instrument for 10 minutes. RIPA extracted lysates were then fractionated with ammonium sulfate with percent increments of 20. These fractions were then separated via SDS-PAGE and relevant probe-labeling was determined by anti-biotin (1:500, ab1227, Abcam) western blotting as above. A parallel gel was silver stained using the Pierce silver stain kit. Relevant gel slices from the 80 percent fraction were excised and PGK1 identity was determined by LC-MS/MS by the Scripps Center for Metabolomics and Mass Spectrometry. Follow up shRNA knock down studies confirmed PGK1 as the target within this fraction.

Dye-based thermal denaturation assay.

Thermal denaturation experiments were performed using a Protein Thermal Shift Dye Kit (ThermoFisher, 4461146). Reactions contained 2 μM recombinant PGK1 with the indicated dose of aqueously-delivered CBR-470-1 with 1x supplied thermal shift dye and reaction buffer in 20uL reaction volumes. Fluorescence values were recorded using a Viia7 Real-Time PCR instrument according to supplied instructions.

Recombinant PGK1 assay.

PGK1 enzymatic activity in the forward direction was measured with a coupled enzymatic assay34. Three PGK1 conditions were prepared by dissolving recombinant PGK1 in potassium phosphate buffer (10 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM MgSO4, pH 7.0), and transferring the aliquots of PGK1 solution to the microtubes being treated with same amount of DMSO and indicated concentrations of CBR-470-1. Final concentration of PGK1 is 20 ng/mL and DMSO is 1% for each sample. Two blank conditions, 0 μM and 100 μM of CBR-470-1 with no PGK1, were also prepared for the control measurements. All PGK1 samples and blank samples were pre-incubated for 20 minutes and then transferred to the UV-transparent 96 well plate (Corning). The assay solution (10 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM G3P, 0.6 mM NAD+, 200 mM Glycine, 0.4 mM ADP, pH 7.0) was activated by adding GAPDH with 10 μg/mL final concentration, and then the assay solution was added to the wells containing PGK1 samples and blank samples. The change in absorbance at 340 nm at room temperature was measured every 20 seconds for 45 minutes, by Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader. Each condition was performed with three independent replications.

Isothermal dose response profiling of PGK1.

In-vitro thermal profiling assay for recombinant proteins was performed by dissolving pure recombinant PGK1 and GAPDH into PBS, and dividing equal amount of mixture into 9 aliquots. Each aliquot was transferred to 0.2 mL PCR microtubes being treated with different amounts of CBR-470-1 added from DMSO stock, and equal amount of DMSO for the control. Each microtube contains 50 μL of mixture with final concentration of 45 μg/mL for each protein and DMSO concentration 1 % with following final concentrations of CBR-470-1; 0 μM, 0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, 1 μM, 3 μM, 10 μM, 33 μM, 100 μM, 333 μM. After 30 minutes incubation at 25°C, samples were heated at 57°C for 3 minutes followed by cooling at 25°C for 3 minutes using Thermal Cycler. The heated samples were centrifuged at 17,000g for 20 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were transferred to new Eppendorf tubes. Control experiments were performed with heating at 25°C for 3 minutes, instead of 57°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

Metabolite Treatments and HMW-KEAP1 screening.

For in vitro screening of glycolytic metabolites, HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-KEAP1 were lysed by snap-freeze-thaw cycles (3x) in PBS, pH 7.4, containing EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor (Roche). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and the supernatants normalized for concentration by Bradford reagent (2 mg/mL). Concentrated stocks of each metabolite were made in PBS, which were added to the lysate samples for the final indicated concentrations and incubated at 37˚C for 2.5 hours with shaking. Following incubation, samples were denatured with 6 M urea and processed for SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Methylglyoxal (40% v/v with H2O), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP), dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) were all obtained from Sigma Aldrich and used as PBS stocks. In situ metabolite treatments were performed in HEK293T cells 24 hours after transfection of FLAG-KEAP1, treated with MGx (1 or 5 mM) in H2O (Sigma) or equivalent vehicle alone for 8 hours. Cells were collected by scraping, washed in PBS and centrifuged, and lysed in urea lysis buffer and analysis by SDS-PAGE and western blot. Dose-response experiments were performed with high purity MGx was prepared by acidic hydrolysis of MG-1,1-dimethylacetal (Sigma Aldrich) followed by fractional distillation under reduced pressure and colorimetric calibration of the distillates, as previously reported33. For in vitro MGx dose-response dimerization of KEAP1, HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-KEAP1 were lysed in PBS as indicated above, then serial dilutions of high purity MGx in 50 mM Sodium Phosphate, pH 7.4, were added to the equal volume of lysate aliquots with final protein concentration of 1 mg/mL. Each mixture was incubated at 37°C for 8 hours with rotating, HMW-KEAP1 formation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blot.

For studies with recombinant KEAP1, FLAG-KEAP1 was expressed in HEK293T cells from transient transfection of the Flag-Keap1 plasmid (Addgene plasmid #28023). FLAG-KEAP1 protein was immunopurified after overnight incubation at 4 degrees with anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma) in RIPA buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors, eluted with 3xFLAG peptide (150 ng/mL) in PBS, and desalted completely into PBS. 500 ng of purified FLAG-KEAP1 protein was then subjected to reducing conditions with the addition of either TCEP (0.1 mM) or DTT (1 mM) for 10 minutes at 37 degrees. MGx was then added to a final concentration of 5 mM and incubated for 2 hours at 37 degrees. Reactions were quenched by the addition of 50 μL of 4x sample buffer and subsequent boiling for 10 minutes. 12 μL of this reaction was then separated by SDS-PAGE and the presence of HMW-KEAP1 evaluated by anti-FLAG Western blotting as described or by silver staining using the Pierce Silver Stain Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Site-directed Mutagenesis of KEAP1

KEAP1 mutants were generated with PCR primers in Extended Data Table 1 according to the Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit protocol (F-541, Thermo Scientific) and the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit protocol (200523, Agilent). Mutant KEAP1 plasmids were verified by sequencing [CMV (forward), wild-type primers in the middle of KEAP1 sequence (forward) and BGH (reverse)], and were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells in the same manner as wild type KEAP1. Screening of CBR-470-1-induced HMW-KEAP1 formation with mutant constructs was performed just as with wild type KEAP1, after 8 hour CBR-470-1 treatment (20 μM). Following treatment, cells were harvested and prepared for SDS-PAGE and western blotting as indicated above.

SILAC cell culture methods and proteomic sample preparation.

SILAC labeling was performed by growing cells for at least five passages in lysine- and arginine-free SILAC medium (RPMI, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% P/S. “Light” and “heavy” media were supplemented with natural lysine and arginine (0.1 mg/mL), and 13C-, 15N-labeled lysine and arginine (0.1 mg/mL), respectively.

General protein digestion for LC-MS/MS analysis was performed by dissolving protein (e.g. whole lysate or enriched proteins) in digestion buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM NH4HCO3, pH 8.0), followed by disulfide reduction with DTT (10 mM, 40 minutes, 50 ˚C), alkylation (iodoacetamide, 15 mM, 30 min, room temperature, protected from light) and quenching (DTT, 5mM, 10 minutes, room temperature). The proteome solution was diluted 4-fold with ammonium bicarbonate solution (50 mM, pH 8.0), CaCl2 added (1 mM) and digested with sequencing grade trypsin (∼1:100 enzyme/protein ratio; Promega) at 37 ˚C while rotating overnight. Peptide digestion reactions were stopped by acidification to pH 2-3 with 1% formic acid, and peptides were then desalted on ZipTip C18 tips (100 μL, Millipore), dried under vacuum, resuspended with LC-MS grade water (Sigma Aldrich), and then lyophilized. Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in LC-MS/MS Buffer A (H2O with 0.1% formic acid, LC-MS grade, Sigma Aldrich) for proteomic analysis.

Proteomic LC-MS/MS and Data Analysis.

LC-MS/MS experiments were performed with an Easy-nLC 1000 ultra-high pressure LC system (ThermoFisher) using a PepMap RSLC C18 column heated to 40˚C (column: 75 μm x 15 cm; 3 μm, 100 Å) coupled to a Q Exactive HF orbitrap and Easy-Spray nanosource (ThermoFisher). Digested peptides (500 ng) in MS/MS Buffer A were injected onto the column and separated using the following gradient of buffer B (0.1% Formic acid acetonitrile) at 300 nL/min: 0-2% buffer B over 10 minutes, 2-40% buffer B over 120 minutes, 40-70% buffer B over 10 minutes, and 70-100% buffer B over 5 minutes. MS/MS spectra were collected from 0 to 150 minutes using a data-dependent, top-20 ion setting with the following settings: full MS scans were acquired at a resolution of 120,000, scan range of 400-1600 m/z, maximum IT of 50 ms, AGC target of 1e6, and data collection in profile mode. MS2 scans was performed by HCD fragmentation with a resolution of 15,000, AGC target of 1e5, maximum IT of 30 ms, NCE of 26, and data type in centroid mode. Isolation window for precursor ions was set to 1.5 m/z with an underfill ratio of 0.5%. Peptides with charge state >5, 1 and undefined were excluded and dynamic exclusion was set to eight seconds. Furthermore, S-lens RF level was set to 60 with a spray voltage value of 2.60kV and ionization chamber temperature of 300 ˚C.

MS2 files were generated and searched using the ProLuCID algorithm in the Integrated Proteomics Pipeline (IP2) software platform. Human proteome data were searched using a concatenated target/decoy UniProt database (UniProt_Human_reviewed_04-10-2017.fasta). Basic searches were performed with the following search parameters: HCD fragmentation method; monoisotopic precursor ions; high resolution mode (3 isotopic peaks); precursor mass range 600-6,000 and initial fragment tolerance at 600 p.p.m.; enzyme cleavage specificity at C-terminal lysine and arginine residues with 3 missed cleavage sites permitted; static modification of +57.02146 on cysteine (carboxyamidomethylation); two total differential modification sites per peptide, including oxidized methionine (+15.9949); primary scoring type by XCorr and secondary by Zscore; minimum peptide length of six residues with a candidate peptide threshold of 500. A minimum of one peptide per protein and half-tryptic peptide specificity were required. Starting statistics were performed with a Δmass cutoff = 15 p.p.m. with modstat, and trypstat settings. False-discovery rates of peptide (sfp) were set to 1%, peptide modification requirement (-m) was set to 1, and spectra display mode (-t) was set to 1. SILAC searchers were performed as above with “light” and “heavy” database searches of MS1 and MS2 files by including static modification of +8.014168 for lysine and +10.0083 for arginine in a parallel heavy search. SILAC quantification was peformed using the QuantCompare algorithm, with a mass tolerance of 10 p.p.m. or less in cases where co-eluting peptide interfere. In general all quantified peptides has mass error within 3 p.p.m..

Quantitative Proteomic Detection of Potential KEAP1 Modification Sites

Quantitative surface mapping with SILAC quantitative proteomics was performed with “heavy” and “light” labeled HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-KEAP1. Cells were incubated with DMSO alone (light cells) or CBR-470-1 (20 μM, heavy cells) for 8 hours. After incubation cells were scraped, washed with PBS (3x) and combined prior to lysis in Urea lysis buffer [8 M Urea, 50 mM NH4HCO3, nicotinamide (1 mM), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich), and EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor (Roche), pH 8.0] by sonication at 4 ˚C. After sonication insoluble debris was cleared by centrifugation (17,000 g, 10 min), diluted with Milli-Q water to give 1 M urea, and lysate was incubated with Anti-FLAG M2 resin (100 μL slurry, A2220, Sigma Aldrich) at 4 ˚C overnight while rotating. For SILAC label-swap experiments, “light” HEK293T cells were incubated with CBR-470-1 and “heavy” cells were incubated with DMSO and processed as above. FLAG resin was washed with PBS (7×1 mL), FLAG-KEAP1 protein eluted with glycine-HCl buffer (0.1 M glycine, pH 3.5, 2×500 μL), followed by 8 M urea (2×100 μL). The combined eluent was brought up to 8 M urea total concentration and processed for trypsin digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis as indicated above.

The SILAC maps were generated by comparing SILAC ratios for each peptide, relative to the median value for all KEAP1 peptides. SILAC ratios were converted to Log2 values and plotted to visualize peptides that are significantly perturbed, for example by modification, relative to the rest of the protein. A minimum of three SILAC ratios for each peptide was required for inclusion in KEAP1 surface maps, which allowed for ∼85-90% coverage of the KEAP1 protein. Missing sequences were caused by the lack or close spacing of trypitc sites, resulting in inadequate peptides for MS/MS detection.

In vitro MGx- Peptide Reactions

‘CR’ peptide was synthesized using standard solid phase peptide synthesis with FMOC-protected amino acids on MBHA rink amide resin. Peptides were cleaved in a solution of 94% trifluoroacetic acid, 2.5% triisopropyl silane, 2.5% H2O, 1% β-mercaptoethanol (βME) and precipitated with ether. Peptide identity was confirmed using an Agilent 1100 series LC-MS. Peptides were purified via reverse phase HPLC on an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 250mm column and dried via lyophilization. For methylglyoxal reactions CR peptide (1 mM) was incubated with 12.5 mM methylglyoxal (diluted from 40% solution in water; Sigma Aldrich) or equivalent amount of water (mock) in 1x PBS pH 7.4 at 37°C overnight. Reactions were diluted 1:25 in 95/5 H2O/Acetonitrile + 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and analyzed by LC-MS.

For NMR experiments, approximately 1.5 mg of the CR or CR-MGx crosslinked peptide was purified by reverse phase HPLC, lyophilized and dissolved in 700 μL d6-DMSO. The peptides was dried via lyophilization. All NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance II+ 500 MHz 11.7 Tesla NMR. Data was processed and plotted in Bruker Topspin 3.5. CR peptide NMR experiments were run with a spectral width of 8.5 for 2D experiments (in both dimensions) and 15 for 1D proton NMR with a pulse width of 13.5 μs and an interscan delay of 3 s. For the proton NMR, 256 scans were taken. For the COSY-DQF experiment, 128 and 2048 complex points were acquired in the F1 and F2 dimensions respectively, with 8 scans per point. For the TOCSY experiment, a mixing time of 60 μs was used, and 256 and 1024 complex points were acquired with 8 scans per point. All CR-MGx peptide NMR experiments were run with a spectral width of 13 (in both dimensions) with a pulse width of 11.5 μs and an interscan delay of 2.2 s. For the proton NMR, 256 scans were taken. For the COSY-DQF experiment, 128 and 2048 complex points were acquired in the F1 and F2 dimensions respectively, with 8 scans per point. For the TOCSY experiment, a mixing time of 80 μs was used, and 256 and 1024 complex points were acquired with 8 scans per point.

In-gel digestion of KEAP1

Targeted proteomic analyses of KEAP1 protein were performed by running anti-FLAG enriched HMW-KEAP1 and LMW-KEAP1 (from both CBR-470-1 or MGx treatments as above) on SDS-PAGE gels, and isolated gel pieces were digested in-gel with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega), as previously reported35. Tryptic peptides from in-gel tryptic digestions were dissolved in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 2 mM of CaCl2, and further digested with mass spectrometry-grade chymotrypsin (Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Chymotryptic digestion reactions were stopped by acidification, and desalted on Ziptip C18 tips.

Targeted proteomic analysis of crosslinked KEAP1 peptides

Double digested KEAP1 peptides from isolated HMW-KEAP1 and monomeric KEAP1 were analyzed by LC-MS/MS on an Easy-nLC 1000 ultra-high pressure LC system coupled to a Q Exactive HF orbitrap and Easy-Spray nanosource as indicated above. Candidate peptides were initially searched by manual inspection of chromatograms and MS1 spectra for m/z values of peptide candidates from predicted digestion sites, crosslink sites and differential presence in HMW- and monomeric KEAP1 from both CBR-470-1 and MGx treated samples. Extracted MS1 ions of the candidates were present in HMW-KEAP1 digests but not in LMW-KEAP1 digests. MS/MS spectra and PRM experiments were collected on the same instrument using the following settings: Global and general settings included lock masses of off, chromatography peak width of 15 seconds, polarity of positive, in-source CID of 0.0 eV, inclusion list set to ‘on,’ and an m/z value of the target parent ion with its charge state in the inclusion list. MS2 scans were performed by HCD fragmentation with microscans of 1, resolution of 120,000, AGC target of 5e5, maximum IT of 200 ms, loop count of 1, MSX count of 1, isolation window of 2.0 m/z, isolation offset of 0.0 m/z, NCE of 16, and spectrum data type in profile mode. Furthermore, S-lens RF level was set to 60 with a spray voltage value of 2.20kV and ionization chamber temperature of 275 ˚C. Targeted PRM experiments were performed on CBR-470-1-, MGx-induced HMW-KEAP1 and monomeric KEAP1 samples.

UVB Skin Damage Model.

32 5-week old Balb/c male mice were randomized into 4 groups of 8 animals such that each group had similar body weight means. Mice were prepared for removal of hair from their entire back two days prior to UVB exposure (day 3) by using an electric shaver and depilatory cream. On day 5, mice received exposure to UVB (200 mJ/cm2) produced by a broad band UVB lamp (Dermapal UVB Rev 2) powered by a Kernel UV Phototherapy system. UVB exposure was confined to a rectangular area of ∼8 cm2 by a lead shielding mask. UVB doses were confirmed by dosimeter measurements (Daavlin X96). Sham animals were shaved but received no UVB treatment. Mice were dosed from day 0 to study end at day 10 via oral gavage twice daily (CBR-470-2, 50mg/kg BID PO; BARD, 3 mg/kg PO; Vehicle, 0.5% methyl cellulose/0.5% Tween80). Mice were monitored daily for body weight changes and erythema scoring from days 5 to 10. Mice were sacrificed at day 10 and specimens collected for histological analysis from the wounded area. These studies were performed at Biomodels, LLC (Watertown, MA). Blinded erythema scores were recorded by a blinded, trained investigator according to established in house scale. In short, a scale of 0 to 4 was generated with a score of 0 referring to normal skin and a score of 4 indicating severe ulceration.

Percent wounded area measurements.

Photographs of animals on day 10 of the study were taken such that the distance from camera, aperture, and exposure settings were identical. Images were then cropped such that only the shaved, wounded area encompassed the imaging field. These images were then processed with a custom ImageJ macro which first performed a three color image deconvolution to separate the red content of the image36. The thresholding function within ImageJ software was then used to separate clear sites of wounding from red background present in normal skin. Red content corresponding to wounds was then quantified as a fraction of the whole imaging field and reported as percent wounded area.

Epidermal thickness measurements.

H&E stained skin sections corresponding to the wounded area were generated by Histotox Labs and accessed via pathxl software. 24 individual measurements of epidermal thickness from 8 sections spanning a 400 μm step distance were recorded per animal by a non-blinded, trained investigator. These measurements were then averaged to generate a mean epidermal thickness measurement per animal.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1.

A high throughput screen identifies a non-covalent NRF2 activator chemical series which activate a robust NRF2 transcriptional program in multiple cell types. a, Plate-based Z-scores of ARE-LUC luminance measurements of all test compounds from a 30k compound screen in IMR32 cells. b, Structure of screening hit CBR-470-0. c, Relative ARE-LUC luminance measurements from IMR32 cells treated for 24 hours with a concentration response of CBR-470-0 and reported NRF2 activators TBHQ and AI-1 (n=3 biologically independent samples, mean and s.e.m.). d, LC-MS quantification of CBR-470-1 (50μM) incubated in the presence or absence of GSH (1mM) in PBS for 1 hour (left) and 48 hours (right). Relative ion intensities within each time point were compared with representative chromatograms shown (n=2). e, Relative ARE-LUC luminance values from IMR32 cells transfected with wild type (wt) or mutant (mt, two core nucleotides necessary for NRF2 binding were changed from GC to AT) ARE-LUC reporter constructs and treated with the indicated doses of CBR-470-1 for 24 hours (n=3, mean and s.e.m.). f, Relative abundance of NRF2-dependent transcripts as determined by qRT-PCR from IMR32 cells treated for 24 hours with 5 μM CBR-470-1 (n=3). g, Western blot analyses of total NRF2 protein content or NRF2-controlled genes (NQO1, HMOX1) from IMR32 cells treated for 24 hours with 5 μM CBR-470-1 (n=5). h, Western blot analyses of total NRF2 protein content from the indicated cell types treated for 4 hours with 5 μM CBR-470-1 (n=3). i, Relative expression levels of NQO1 and HMOX1 from the indicated cell types treated for 24 hours with 5 μM CBR-470-1 (n=3, mean and s.d.). j, Relative ARE-LUC luminescence values from HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated shRNA constructs and pTI-ARE-LUC and then treated with TBHQ (10 μM) or CBR-470-1 (5 μM) for 24 hours (n=3). k, Relative viability measurements of SH-SY5Y cells treated with either CBR-470-1 (5 μM) or TBHQ (10 μM) for 48 hours and then challenged with the indicated doses of tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) for 8 hours (n=4). Data are mean and s.d. of biologically independent samples (P* < 0.05, P** < 0.005, P*** < 0.001, univariate two-sided t-test).

Extended Data Figure 2.

CBR-470-2 pharmacokinetics and in vivo activity. a, Structure of CBR-470-2. b, Relative ARE-LUC luminance values from IMR32 cells transfected with pTI-ARE-LUC and treated with the indicated doses of CBR-470-1 and CBR-470-2 for 24 hours (n=3 biologically independent samples). c, Plasma concentrations of CBR-470-2 from mice treated with a single 20 mg/kg dose of compound. (n=3 animals, mean and s.e.m.). d, e, Relative transcript levels of Nqo1 and Hmox1 from mouse epidermal keratinocytes (d) and mouse dermal fibroblasts (e) treated for 24 hours with the indicated doses of compound (n=3 biologically independent samples, mean and s.d.). f, Blinded erythema scores from mice treated with vehicle, CBR-470-2 or Bardoxolone after UV exposure (n=8 animals, P* < 0.05, P*** < 0.005, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, mean and s.e.m.). g, Representative images of UV-exposed dorsal regions of animals at day 10 of the study.

Extended Data Figure 3.

A photoactivatable affinity probe-based approach identifies PGK1 as the relevant cellular target of CBR-470-1. a, Structure of CBR-470-PAP. b, Relative ARE-LUC luminance values from IMR32 cells transfected with pTI-ARE-LUC and then treated with the indicated doses of CBR-470-PAP for 24 hours (n=3). c, Silver staining and anti-biotin Western blots of ammonium sulfate fractionated lysates from UV-irradiated IMR32 cells treated with 5 μM for 1 hour with or without CBR-470-1 competition (250 μM)(n=3). Shown on the right are initial proteomic target results from gel-band digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis. d, Anti-biotin Western blots from in vitro crosslinking assays with recombinant PGK1 and EBP1 in the presence of the indicated doses of CBR-470-PAP (n=2). e, Anti-biotin Western blot analyses from an in vitro crosslinking assay with recombinant PGK1 in the presence of CBR-470-PAP (1 μM) and indicated concentration of soluble CBR-470-1 competitor (n=2). f, Anti-biotin Western blot analyses of cells treated with 5 μM CBR-470-PAP after transduction with anti-PGK1 and anti-EBP1 shRNA for 48 hours. Depletion of PGK1 protein selectively reduces CBR-470-PAP-dependent labeling (n=2). g, Dye-based thermal denaturation assay with recombinant PGK1 in the presence CBR-470-1 (20 μM) or vehicle alone (n=3). Calculated Tm values are listed. h, i, Dose-dependent thermal stability assay of recombinant PGK1 and GAPDH in the presence of increasing doses of CBR-470-1 near the Tm of both proteins (57°C) (h) (n=5) or room temperature (i) (n=3). Western blot of sample supernatants after centrifugation (13,000 rpm) detected total PGK1 and GAPDH protein, which were plotted in Prism (below). j, ARE-LUC reporter activity in HEK293T cells with transient shRNA knockdown of ENO1 (n=3). Data shown represent mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

Extended Data Figure 4.

CBR-470-1 inhibits PGK1 in vitro and in situ. a, Schematic of the GAPDH/PGK1 coupled assay. Pre-equilibration of the GAPDH reaction (top left) results in an NAD+/NADH equilibrium, which upon addition of PGK1 and ADP pulls the reaction to the right producing more NADH. Monitoring NADH absorbance after addition of PGK1 (bottom right) can be used to monitor PGK1 activity in the forward direction (right). Kinetic monitoring of NADH absorbance (340 nm) after established equilibrium with GAPDH shows little change (black curve), but is significantly increased upon addition of PGK1, pulling the equilibrium to the right (red curve). b, CBR-470-1 does not affect the GAPDH equilibrium alone, but significantly inhibits PGK1-dependent activity and accumulation of NADH (n=5). c, d, Relative level of central metabolites in IMR32 cells treated with viral knockdown of PGK1 for 72 hours (c) (n=4) and with CBR-470-1 relative DMSO alone for the indicative times (d) (n=3). Each metabolite is normalized to the control condition at each time point. Univariate two-sided t-test (Extended Data Fig 5b); data shown represent mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

Extended Data Figure 5.

Modulation of PGK1 induces HMW-KEAP1. a, Anti-pgK (phosphoglyceryl-lysine) and anti-GAPDH Western blots analysis of CBR-470-1 or DMSO-treated IMR32 cells at early (30 min) and late (24 hr) time points (n=6). b, Anti-FLAG (left) and anti-pgK (right) Western blot analysis of affinity purified FLAG-KEAP1 from HEK293T cells treated with DMSO or CBR-470-1 for 30 min. Duplicate samples were run under non-reducing (left) and reducing (DTT, right) conditions (n=6). c, Densitometry quantification of total endogenous KEAP1 levels (combined bands at ∼70 and 140 kDa) in IMR32 cells treated with DMSO or CBR-470-1 for the indicated times (n=6). d, Western blot detection of FLAG-KEAP1 in HEK293T cells comparing no-reducing reagent to DTT (left), and stability of CBR-470-1-dependent HMW-KEAP1 to the presence of DTT (12.5 mM final concentration, middle) and beta-mercaptoethanol (5% v/v final concentration, right) during sample preparation. treated with DMSO or CBR-470-1 for 8 hours (n=8). e, Time-dependent CBR-470-1 treatment of HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-KEAP1. Time-dependent assays were run with 20 μM CBR-470-1 with Western blot analysis at the indicated time-points (n=8). f, g, Western blot detection (f) and quantification (g) of endogenous KEAP1 and β-actin in IMR32 cells treated with DMSO or CBR-470-1 for the indicated times (n=6). Arrows indicate monomeric (∼70 kDa) and HMW-KEAP1 (∼140 kDa) bands. h, i, Western blot (h) detection and quantification (i) of FLAG-KEAP1 in HEK293T cells exposed to increasing doses of CBR-470-1 (n=3). j, Kinetic qRT-PCR measurement of NQO1 mRNA levels from IMR32 cells treated with tBHQ (10 μM) or CBR-470-1 (10 μM) for the indicated times (n=3). k, Quantification of HMW-KEAP1 formation upon treatment with CBR-470-1 or the direct KEAP1 alkylator TBHQ, in the presence or absence of reduced glutathione (GSH) or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (n=3). All measurements taken after 8 hour of treatment in FLAG-KEAP1 expressing HEK293T cells. l, Transient shRNA knockdown of PGK1 induced HMW-KEAP1 formation, which was blocked by co-treatment of cells by GSH (n=3). m, Anti-FLAG Western blot analysis of FLAG-KEAP1 monomer and HMW-KEAP1 fraction with dose-dependent incubation of distilled MGx in lysate from HEK-293T cells expressing FLAG-KEAP1 (n=4). n, SDS-PAGE gel (silver stain) and anti-FLAG Western blot analysis of purified KEAP1 treated with the MGx under the indicated reducing conditions for 2 hr at 37°C (n=3). Purified protein reactions were quenched in 4x SDS loading buffer containing βME and processed for gel analysis as in (d). Data shown represent mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

Extended Data Figure 6.

MGx and glyoxylase activity regulates NRF2 activation. CBR-470-1 causes elevated MGx levels in cells. a, Schematic depicting chemical derivatization and trapping of cellular MGx for analysis by targeted metabolomics using two unique fragment ions. b, c, Daughter ion fragments (b) and resulting MS/MS quantification of MGx levels (c) in IMR32 cells treated with CBR-470-1, relative to DMSO (n=4). d, Quantitative LC-MS/MS measurement of cellular MGx levels in IMR32 cells treated for 2 hours with CBR-470-1 or co-treated for 2 hours with CBR-470-1 and NAC (2 mM) relative to DMSO (n=4). e, Relative ARE-LUC luminance values from IMR32 cells transfected with pTI-ARE-LUC and co-treated with the indicated doses of CBR-470-1 and GSH (n=3). f, Relative levels of transcripts NQO1 and HMOX1 from IMR32 cells co-treated with CBR-470-1 (10 μM) and the indicated concentrations of GSH for 24 hours (n=3). g, Fractional ARE-LUC values from HEK293T cells transiently co-transfected with pTI-ARE-LUC and the indicated shRNAs and then treated for 24 hours with the indicated doses of CBR-470-1 (n=3). h, ARE-LUC reporter activity in HEK293T cells treated with CBR-470-1 alone (black) and with a cell-permeable small molecule GLO1 inhibitor (red) (n=3). Univariate two-sided t-test (Extended Data Fig 7d, h); data are mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

Extended Data Figure 7.

Schematic of SILAC-based proteomic mapping of KEAP1 modifications in response to CBR-470-1 and NMR characterization of CR-MGx peptide. a, Stable isotope-labeled cells (stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture, SILAC) expressing FLAG-tagged KEAP1 were treated with vehicle (‘light’) and CBR-470-1 or MGx (‘heavy’), respectively. Subsequent mixing of the cell lysates, anti-FLAG enrichment, tryptic digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis permitted detection of unmodified portions of KEAP1, which retained ∼1:1 SILAC ratios relative to the median ratios for all detected KEAP1 peptides. In contrast, peptides that are modified under one condition will no longer match tryptic MS/MS searches, resulting skewed SILAC ratios that “drop out” (bottom). b, SILAC ratios for individual tryptic peptides from FLAG-KEAP1 enriched DMSO treated ‘light’ cells and CBR-470-1 treated ‘heavy’ cells, relative to the median ratio of all KEAP1 peptides. Highlighted tryptic peptides were significantly reduced by 3- to 4-fold upon relative to the KEAP1 median, indicative of structural modification (n=8). c, Structural depiction of potentially modified stretches of human KEAP1 (red) using published x-ray crystal structure of the BTB (PDB: 4CXI) and KELCH (PDB: 1U6D) domains. Intervening protein stretches are depicted as unstructured loops in green. d, SILAC ratios for individual tryptic peptides from FLAG-KEAP1 enriched MGx treated ‘heavy’ cell lysates and no treated ‘light’ cell lysates, relative to the median ratio of all KEAP1 peptides. Highlighted tryptic peptides were significantly reduced by 2- to 2.5- fold upon relative to the KEAP1 median, indicative of structural modification (n=12). e, Representative Western blotting analysis of FLAG-KEAP1 dimerization from HEK293T cells pre-treated with Bardoxolone methyl followed by CBR-470-1 treatment for 4 hours (n=3). f, 1H-NMR of CR-MGx peptide (isolated product of MGx incubated with Ac-NH-VVCGGGRGG-C(O)NH2 peptide). 1H NMR (500MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 12.17 (s, 1H), 12.02 (s, 1H), 8.44 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.32-8.29 (m, 2H), 8.23 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 4.33-4.28 (m, 1H), 4.25-4.16 (m, 3H), 3.83 (dd, J = 6.9 Hz, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 3.79-3.67 (m, 6H), 3.63 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.54 (dd, J = 4.9 Hz, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 3.18-3.13 (m, 2H), 3.04 (dd, J = 4.9 Hz, J = 13.9 Hz, 1H), 2.88 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 2.04 (s, 3H), 1.96 (sep, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.87 (s, 3H), 1.80-1.75 (m, 1H), 1.56-1.47 (m, 3H), .87-.82 (m, 12H). g, 1H-NMR of CR peptide (Ac-NH-VVCGGGRGG-C(O)NH2). 1H NMR (500MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 8.27-8.24 (m, 2H), 8.18 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.13-8.08 (m, 3H), 8.04 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.86 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.10 (s, 1H), 4.39 (dt, J = 5.6 Hz, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (dt, J = 5.7 Hz, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.21-4.13 (m, 2H), 3.82-3.70 (m, 8H), 3.64 (d, J = 5.8, 2H), 3.08 (dt, J = 6.5 Hz, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.80-2.67 (m, 2H), 2.43 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 1.94 (sep, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.85 (s, 3H), 1.75-1.68 (m, 1H), 1.54-1.42 (m, 3H), .85-.81 (m, 12H) h, 1H-1H TOCSY of CR-MGx peptide. i, Peak assignment for CR-MGx peptide TOCSY spectrum. Data are mean ± SEM of biologically independent samples.

Extended Data Figure 8.

MS2 analysis of CR-MGx crosslinked KEAP1 peptide. a, Targeted Parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) transitions (n=6). b, Annotated MS2 spectrum from the crosslinked C151-R135 KEAP1 peptide.

Extended Data Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time qPCR and cloning experiments.

| Gene | Forward Primer Sequence | Reverse Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| NQOl | GCCTCCTTCATGGCATAGTT | GGACTGCACCAGAGCCAT |

| HMOX1 | GAGTGTAAGGACCCATCGGA | GCCAGCAACAAAGTGCAAG |

| ME1 | GGAGACGAAATGCATTCACA | ACGAATTCATGGAGGCAGTT |

| GCLM | GCTTCTTGGAAACTTGCTTCA | CTGTGTGATGCCACCAGATT |

| TXNRD1 | TCAGGGCCGTTCATTTTTAG | GATCTGCCCGTTGTGTTTG |

| FTH1 | GGCAAAGTTCTTCAAAGCCA | CATCAACCGCCAGATCAAC |

| GSR | TTGGAAAGCCATAATCAGCA | CAAGCTGGGTGGCACTTG |

| EPHX1 | CTTCACGTGGATGAAGTGGA | CTGGCGGAATGAATTTGACT |

| ABCC2 | GGGATCTCTTCCACACTGGAT | CATACAGGCCCTGAAGAGGA |

| PRDX1 | GGGCACACAAAGGTGAAGTC | GCTGTTATGCCAGATGGTCAG |

| NQ02 | TGCGTAGTCTCTCTTCAGCG | GCAACTCCTAGAGCGGTCCT |

| GSTM3 | GGGTGATCTTGTTCTTCCCA | GGGGAAGCTCCTGACTATGA |

| SOD1 | CCACACCTTCACTGGTCCAT | CTAGCGAGTTATGGCGACG |

| TXNRD1 | TCAGGGCCGTTCATTTTTAG | GATCTGCCCGTTGTGTTTG |

| GSTP1 | CTCAAAAGGCTTCAGTTGCC | ACCTCCGCTGCAAATACATC |

| GCLC | CTTTCTCCCCAGACAGGACC | CAAGGACGTTCTCAAGTGGG |

| GLOl | TGGATTAGCGTCATTCCAAG | GCGGACCCCAGTACCAAG |

| PGK1 | CTTGGGACAGCAGCCTTAAT | CAAGCTGGACGTTAAAGGGA |

| TUBG1 | ATCTGCCTCCCGGTCTATG | TACCTGTCGGAACATGGAGG |

| Mutation | Primer (Forward) | Primer (Reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| C23S | 5’-/5Phos/GCA GGG GAC GCG GTG ATG TAC -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/CCC CTC AGG AGA CTG TGA CTG CAG GGG C -3’ |

| C38S | 5’-/5Phos/GCC CTC CCA GCA TGG CAA -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/GTC ACC TCC GCC TTG GAC TCA GT -3’ |

| C151S | 5’-/5Phos/TGA ACG GTG CTG TCA TGT ACC AGATC -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/TGA CGT GGA GGA CAG ACT TCT CGC -3’ |

| C273S | 5’-/5Phos/CCG AAC TTC CTG CAG ATG CAG CT -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/CGT CAA CGA GTG GGA GCG CAC G -3’ |

| C288S | 5’-/5Phos/GTC CGA CTC CCG CTG CAA GGA CT -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/TGC AGG ATC TCG GAC TTC TGC AGC T -3’ |

| C396S | 5’-/5Phos/GAC CAA TCA GTG GTC GCC CTG -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/ATG GGG TTG TAA GAG TCC AGG GC -3’ |

| C405S | 5’-/5Phos/CGT GCC CCGTAA CCG CAT CG -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/CTC ATG GGG GCG CTG GGC G -3’ |

| K39R | 5’-/5Phos/GCC CTC CCA GCA TGG CAA -3’ | 5’-/5Phos/GTC ACC TCC GCC CTG CAC TCA GT -3’ |

| K39M | 5’-/5Phos/GCC CTC CCA GCA TGG CAA -3’ | 5’- GTC ACC TCC GCC ATG CAC TCA GT -3’ |

| C38S/K39M | 5’-/5Phos/GCC CTC CCA GCA TGG CAA -3’ | 5’- GTC ACC TCC GCC ATG GAC TCA GT -3’ |

| K150M | 5’-/5Phos/TGA ACG GTG CTG TCA TGT ACC AGA TC -3’ | 5’- TGA CGT GGA GGA CAC ACA TCT CGC C -3’ |

| R6A | 5’- GCA GCC AGA TCC CGC GCC TAG CGG GGC TG -3’ | 5’- CAG CCC CGC TAG GCG CGG GAT CTG GCT GC -3’ |

| R15A | 5’- GGG CCT GCT GCG CAT TCC TGC CCC TGC A -3’ | 5’- TGC AGG GGC AGG AAT GCG CAG CAG GCC C -3’ |

| R50A | 5’- CTC CCA GCA TGG CAA CGC CAC CTT CAG CTA CAC -3’ | 5’- GTG TAG CTG AAG GTG GCG TTG CCA TGC TGG GAG -3’ |

| R135A | 5’- CCC A AG GTC ATG GAG GCC CTC ATT GAA TTC GCCT-3’ | 5’- AGG CGA ATT CAA TGA GGG CCT CCA TGA CCT TGG G -3’ |

Extended Data Table 2.

Acquisition parameters used for targeted metabolomic measurements on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Glucose 6-phosphate, G6P; Fructose 1, 6-bisphosphate, FBP; Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, GAP; 1,3- or 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate, BPG; 2- or 3-Phosphoglycerate, 2/3-PG; Phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP; Lactate, Lac; Ribose-5-phosphate, R5P; Glutathione, GSH; Glutathione disulfide, GSSG; Succinate, Succ; Glutamate, Glu; Citrate, Cit; Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NAD+; Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced), NADH; Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, NADP+; Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced), NADPH; Adenosine triphosphate, ATP; Adenosine diphosphate, ADP; 3-Phosphoglyceroyl hydroxamic acid, 3PGha (derivatization product of 1,3-BPG); 2-Methylquinoxaline, 2MQ (derivatization product of MGx). D3-Serine is an isotopically labeled serine standard included in all runs as an internal normalization control.

| Metabolite | Precursor mass |

MSI Resolution |

Product ion |

MS 2 Resolution |

Dwell | Fragmentor | Collision Energy |

Polarity | Retention time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 179.05 | Wide | 89.2 | Unit | 5 | 68 | 12 | Neg | 12.2 |

| G6P | 258.9 | Wide | 138.9 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 5 | Neg | 22.3 |

| FBP | 339.1 | Wide | 96.9 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 20 | Neg | 26.8 |

| GAP | 169 | Wide | 96.9 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 5 | Neg | 22.1 |

| BPG | 264.9 | Wide | 96.9 | Unit | 5 | 86 | 21 | Neg | 30.9 |

| 2/3-PG | 184.98 | Wide | 78.9 | Unit | 5 | 86 | 21 | Neg | 24.6 |

| PEP | 166.97 | Wide | 79 | Unit | 5 | 78 | 9 | Neg | 25.4 |

| Pyruvate | 87.1 | Wide | 43 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 10 | Neg | 14.8 |

| Lac | 89.1 | Wide | 43 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 20 | Neg | 13.5 |

| D3-Serine | 107.05 | Wide | 75.1 | Unit | 5 | 18 | 9 | Neg | 13.9 |

| R5P | 228.7 | Wide | 78.8 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 35 | Neg | 19.9 |

| Serine | 104.2 | Wide | 73.8 | Unit | 5 | 100 | 5 | Neg | 13.9 |

| GSH | 305.7 | Wide | 143.0 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 15 | Neg | 16.7 |

| GSSG | 610.7 | Wide | 305.9 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 15 | Neg | 20.5 |

| Succ | 117 | Wide | 73.1 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 5 | Neg | 18.8 |

| Glu | 146.1 | Wide | 102.1 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 5 | Neg | 15.9 |

| Cit | 191 | Wide | 111 | Unit | 5 | 100 | 5 | Neg | 24.4 |

| NAD+ | 662.1 | Wide | 540 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 15 | Neg | 16.1 |

| NADH | 663.4 | Wide | 407.9 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 35 | Neg | 16.1 |

| NADP+ | 742 | Wide | 619.9 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 25 | Neg | 24.1 |

| NADPH | 743.5 | Wide | 407.8 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 25 | Neg | 24.1 |

| ATP | 506 | Wide | 159 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 25 | Neg | 27.5 |

| ADP | 425.8 | Wide | 134 | Unit | 100 | 100 | 15 | Neg | 26.5 |

| 3PGha | 199.98 | Wide | 199.98 | Unit | 5 | 116 | 0 | Neg | 22.4 |

| 3PGha | 199.98 | Wide | 79 | Unit | 5 | 116 | 15 | Neg | 22.4 |

| 2MO | 145.1 | Wide | 77.1 | Unit | 5 | 100 | 24 | Pos | 8.5 |

| 2MO | 145.1 | Wide | 92.1 | Unit | 5 | 100 | 20 | Pos | 8.5 |

| D3-Serine | 109.07 | Wide | 63.1 | Unit | 5 | 40 | 12 | Pos | 4.3 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Zhu for discussions regarding target identification experiments. Animal experiments were approved by the Scripps Research Institute Institutional Review Board. We are grateful for financial support of this work from the following: Kwanjeong Educational Fellowship (to G.L.); NIH MSTP Training Grant (T32GM007281 to J.S.C.); NIH R00CA175399, R01CA211916, and DP2GM128199 (R.E.M.); V Foundation for Cancer Research (V2015-020 to R.E.M.); The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, and The University of Chicago.

Footnotes

Reporting Summary. Information on experimental design is available the Nature Research Reporting Summary.

Data Availability. RNAseq primary data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under Accession number GSE116642. Source data for all mouse experiments have been provided. Full scans for Western blots and gels are available in the Supplementary Information. All other data are available upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Methods References

- 1.Lin H, Su X & He B Protein lysine acylation and cysteine succination by intermediates of energy metabolism. ACS Chem Biol 7, 947–960 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner GR, et al. A Class of Reactive Acyl-CoA Species Reveals the Non-enzymatic Origins of Protein Acylation. Cell Metab 25, 823–837 e828 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Z, et al. Identification of lysine succinylation as a new post-translational modification. Nature chemical biology 7, 58–63 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moellering RE & Cravatt BF Functional lysine modification by an intrinsically reactive primary glycolytic metabolite. Science 341, 549–553 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinert BT, et al. Acetyl-phosphate is a critical determinant of lysine acetylation in E. coli. Molecular cell 51, 265–272 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabari BR, Zhang D, Allis CD & Zhao Y Metabolic regulation of gene expression through histone acylations. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi A, et al. Oxidative and electrophilic stresses activate Nrf2 through inhibition of ubiquitination activity of Keap1. Molecular and cellular biology 26, 221–229 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo SC, Li X, Henzl MT, Beamer LJ & Hannink M Structure of the Keap1:Nrf2 interface provides mechanistic insight into Nrf2 signaling. The EMBO journal 25, 3605–3617 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaramillo MC & Zhang DD The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes & development 27, 2179–2191 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scannevin RH, et al. Fumarates promote cytoprotection of central nervous system cells against oxidative stress via the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 pathway. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 341, 274–284 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khor TO, et al. Nrf2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Cancer research 66, 11580–11584 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uruno A, et al. The Keap1-Nrf2 system prevents onset of diabetes mellitus. Molecular and cellular biology 33, 2996–3010 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sykiotis GP & Bohmann D Keap1/Nrf2 signaling regulates oxidative stress tolerance and lifespan in Drosophila. Developmental cell 14, 76–85 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]