Abstract

Background:

Complex gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures like endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) require deep sedation or general anesthesia. Comorbidities with the poor physiological condition warrant endotracheal intubation to prevent hypoxia and aspiration. The gastro-laryngeal tube (GLT), a new supraglottic airway device with a separate channel for endoscope looks promising.

Aims:

The aim of the study is to compare the stress response during insertion of GLT and endotracheal intubation (ETT) in patients undergoing upper GI endoscopic procedures like ERCP.

Subjects and Methods:

This control versus comparison study comprised two groups with 30 patients each who underwent ETT and GLT insertion. The standard general anesthesia technique was used. In GLT group, the device was inserted without neuromuscular blocker. In ETT group, injection atracurium 0.5 mg/kg intravenous was administered as muscle relaxant for aiding endotracheal intubation. Hemodynamic parameters and time taken for the insertion of GLT/ETT were recorded.

Statistical Analysis:

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Student's t-test was used to compare quantitative data between the groups. ANOVA test was applied for intragroup comparisons between GLT and ETT groups. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test.

Results:

Heart rate and mean arterial pressure increased from baseline in ETT group, following laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation as well as with GLT insertion. However, the stress response caused by endotracheal intubation was significantly greater than that caused by GLT insertion.

Conclusion:

GLT as an airway device is a safe alternative with decreased stress response compared to endotracheal intubation for upper GI endoscopy procedures.

Keywords: Airway control, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endotracheal intubation, hypoventilation, hypoxia

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a complex and time-consuming procedure, which is generally carried out under moderate sedation which may result in cardiorespiratory complications, particularly drug-induced respiratory depression and airway obstruction.[1,2,3,4] In addition, ERCP is often done as an office procedure in stand-alone centers necessitating meticulous nonoperating room anesthesia (NORA) protocols.

Several patients related and procedure-related factors necessitate the use of general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway for ERCP. Some of them include general frailty and old age, poor nutrition and hydration, poor American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, obstructive jaundice, deranged liver functions, depressed airway reflexes with risk of aspiration, increased chances of hypoxia, and aspiration with deep sedation with an unprotected airway, and depressed tone of muscles of the pharynx. Moderate sedation is associated with pain and high-failure rates,[5] whereas patients undergoing ERCP with deep sedation require same level of care as those under general anaesthesia (GA).[6] Hence, it is prudent to choose either endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway to prevent hypoxia-induced cardiorespiratory complications.

Laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation result in undesirable hemodynamic response, which is probably of little consequence in normal healthy individuals but may be more severe or detrimental in patients with underlying comorbidities. It may lead to complications such as myocardial infarction, left ventricular failure, cerebrovascular accidents, intracranial hypertension, and rise in intraocular pressure.[7] Endotracheal intubation requires the use of neuromuscular blocking drugs which is associated with a longer extubation time compared with the supraglottic airway and thus prolongs the recovery.

A study conducted by Gaitini et al. has established the fact that gastro-laryngeal tube (GLT) is an effective airway for performing the upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy procedures using its endoscopic channel.[8] The stress response between supraglottic airway such as GLT and endotracheal intubation have not been studied and requires further research. This study aims to compare the stress response to insertion of GLT to that of endotracheal intubation in patients undergoing complex upper GI endoscopic procedures like ERCP.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This control versus comparison study comprising two groups with 30 patients each who underwent endotracheal tube (ETT) and GLT intubation was conducted between May 2015 and December 2017, with the primary outcome of comparing the stress response following the insertion of each device, respectively. Approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) was obtained vide IEC No ECR/896/Armed/Inst/MH dated November 3, 2015. The study population included the patients admitted for upper GI endoscopy for performing ERCP at the gastroenterology center. The sample size was calculated based on the study of Bukhari et al.[9] where difference of means comparing the pressor response between the supraglottic airway such as laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and ETT were taken into consideration, and the sample size of 30 was calculated in each group keeping the alpha error of 5% and the power of the study at 80%. Patients undergoing upper GI endoscopic procedures were divided either into the control group (Endotracheal tube [ETT]) or comparison group GLT based on the airway device being used. First, 30 consecutive patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in both the groups in the study.

The inclusion criteria for the study included patients aged between 21 years and 70 years of ASA physical status class (I-IV) irrespective of ERCP grade and height >155 cm. The exclusion criteria included patients with difficult airway, uncontrolled hypertension having contraindication to supraglottic airway device, and patients with esophageal disease with reflux and pregnancy. Preoperative evaluation of all the patients was carried out in preanesthetic clinic.

Written informed consent from the patients was obtained. On arrival, operation theater intravenous (IV) access was established and ASA standards for basic anesthetic monitoring were employed (noninvasive blood pressure, electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry [Oxygen saturation (SpO2)], and temperature along with continuous capnography). Continuous depth of anesthesia monitoring was done with Bispectral index monitor (BIS™ Model A– 2000 Aspect Medical Systems, Inc., Newton, USA). Baseline preinduction values of heart rate (HR), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), and SpO2 were recorded.

Anesthesia management

All patients were preoxygenated with 100% oxygen for 3 min followed by premedication with injection fentanyl 2 μg/kg and induced with the IV injection of propofol (2 mg/kg) till the loss of motor response to jaw thrust with BIS value between 45 and 50. Once adequate jaw relaxation was achieved, the GLT was inserted by a trained, experienced anesthesiologist. In the ETT group, the airway was secured with the appropriate size of ETT after the IV injection of muscle relaxant, atracurium (0.5 mg/kg). The insertion time of ETT was noted from the removal of the face mask before intubation till the appearance of the trace on capnogram after the attachment of the breathing unit of the ventilator.

Patients were placed into the “swimmers” prone position on the fluoroscopy table. Maintenance of anesthesia was carried out with oxygen/nitrous oxide, and the continuous infusion of propofol at the rate of 80–120 μg/kg/min to maintain the adequate depth of anesthesia targeting the Bispectral index monitor (BIS ™ Model A– 2000 Aspect Medical Systems, Inc., Newton, USA) value between 55 and 60 in both the groups. MAP, HR, and SpO2 were recorded at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, and 15 min after the start of anesthesia induction. In ETT group, neuromuscular blockade was reversed and trachea extubated following IV neostigmine 50 μg/kg and glycopyrrolate 10 μg/kg at the end of the procedure. In GLT group, the airway device was removed once regular spontaneous respiration resumed generating a minimum tidal volume of 4 ml/kg.

Staining of GLT/ETT with blood was noted and recorded at the time of removal of airway device. Adverse effects of drugs used for anesthesia were managed as per the standard clinical management guidelines.

Technique of insertion of gastro-laryngeal tube

GLT insertion was done by an anesthesiologist experienced and skilled in insertion of supraglottic devices. Patients were positioned supine or in the sniffing position, GLT was inserted from the center of the mouth with the distal part against the hard palate. As the hypopharynx was reached, the distal part was directed into the esophagus with help of the left index finger [Figure 1a and b].[8] Both balloons of the GLT were inflated with air using a cuff pressure monitor until intraballoon pressure reached 80 cmH2O, and then the deflation valve was pressed to adjust the pressure to 60 cmH2O. Proper positioning of the GLT was confirmed by bilateral chest movement with absence of gastric insufflation and by the presence of a normal capnogram. Number of insertion attempts were recorded. The insertion time of GLT was noted from the removal of the facemask before the insertion of GLT to attachment of the device to the breathing system and the appearance of a normal capnogram trace.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Demonstrating technique of insertion of the gastro-laryngeal tube

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedure

After securing the airway, a 11-mm duodenoscope (Pentax ED-3480 Tokyo, Japan) was passed through the GLT after stabilizing it to prevent the displacement in the GLT group, and the mouth guard was used in ETT group during the placement of the endoscope through the mouth to prevent the damage to the endoscope as well as to help in the suctioning postprocedure in ETT group. The complexity grading of ERCP procedure as described by Cotton et al. was noted in both the groups.[10]

Statistical analysis

It was done using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA) software. Student's t-test (independent samples test) was applied to compare quantitative data between groups GLT and ETT. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Repeated ANOVA was applied for the intragroup comparison.

RESULTS

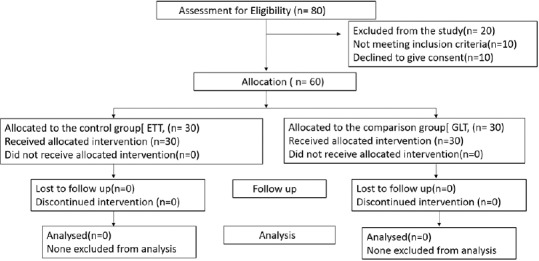

A total of 80 patients were recruited, ten patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, other ten patients did not give consent for the study, and finally, 60 patients were included in the study [Figure 2]. Demographic data including age, sex, height, weight, and ASA grades were comparable between the two groups [Table 1]. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) time taken to insert the airway in seconds was significantly more in the GLT group 29.30 (2.98) as compared to the ETT group 19.60 (1.59) (P = 0.0001) [Table 1].

Figure 2.

Consort flow chart

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| GLT group (n=30) | ETT group (n=30) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years)±SD | 58.33±10.31 | 57.07±9.04 | 0.616* |

| Mean weight (kg)±SD | 63.77±8.44 | 64.20±7.27 | 0.623* |

| Mean height (cm)±SD | 165.47±4.73 | 166.10±5.18 | 0.832* |

| ASA status, n (%) | |||

| II | 11 (36.6) | 11 (36.6) | 0.598# |

| III | 19 (63.3) | 18 (60) | |

| IV | Nil | 1 (3.3) | |

| Sex (male: female), ratio (n) | 16:14 | 17:13 | |

| Mean time taken for insertion of the airway (s) | 29.30±2.98 | 19.60±1.59 | 0.0001* |

| Mean duration of procedure | 50.56±7.70 | 49.62±7.40 | 0.63 |

| Mean±SD dose of propofol (mg) used at time of induction | 123.21±6.28 | 124.04±5.27 | 0.58 |

| Mean±SD dose of propofol (mg) used during maintenance as infusion | 296.49±54.90 | 325.96±52.41 | 0.03 |

*Student’s t-test (independent samples test) was applied, #Chi-square test was applied. P<0.05 considered significant. SD=Standard deviation, ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists, GLT=Gastro-laryngeal tube, ETT=Endotracheal intubation

Table 1 shows mean (SD) duration of procedure and mean (SD) induction dose of the propofol when compared between the groups were not significant. However, mean (SD) maintenance dose of propofol used as an infusion throughout the procedure was significantly higher in the ETT group (P = 0.03).

When the complexity grading of the ERCP procedure was compared between the two groups, the results were insignificant (P = 0.410), but 53.3% of patients in GLT group and 60% of ETT group patients had Grade III complexity during ERCP procedure [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of grading of complexity of upper gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures between two groups

| Grade | Group | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLT | ETT | |||

| I | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.410 |

| II | 12 | 9 | 21 | |

| III | 16 | 18 | 34 | |

| IV | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 30 | 30 | 60 | |

P<0.05 considered significant. Values in group represent the numbers. GLT=Gastro-laryngeal tube, ETT=Endotracheal intubation

There was no statistical difference between two groups when mean (SD) HR was compared at baseline, 1 min and 2 min [Table 3]. However, at 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th, 10th, and 15th min, the ETT group had mean (SD) HR greater than the GLT group, which was statistically significant [P < 0.05, Table 3]. Mean (SD) MAP values between the two groups showed statistically insignificant difference between two groups at baseline, 1 min, 2 min [P > 0.05, Table 4]. However, at 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th, 10th, and 15th min, the ETT group had mean (SD) MAP values greater than the GLT group, which was statistically significant [P < 0.05, Table 4].

Table 3.

Comparison of heart rate between two groups

| HR at (min) | Mean±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLT group (n=30) | ETT group (n=30) | ||

| Baseline | 73.90±6.01 | 74.13±5.44 | 0.875 |

| 1 | 73.37±5.84 | 73.53±4.40 | 0.901 |

| 2 | 74.27±5.51 | 74.60±4.00 | 0.790 |

| 3 | 78.67±5.26 | 85.93±4.47 | 0.001 |

| 4 | 81.53±5.08 | 90.83±4.13 | 0.001 |

| 5 | 83.63±5.21 | 94.63±3.78 | 0.001 |

| 7 | 80.60±5.87 | 88.00±4.27 | 0.001 |

| 10 | 79.03±5.47 | 86.00±4.19 | 0.001 |

| 15 | 77.90±5.09 | 84.47±3.79 | 0.001 |

P<0.05 considered significant. HR=Heart rate, GLT=Gastro-laryngeal tube, ETT=Endotracheal intubation, SD=Standard deviation

Table 4.

Comparison of mean arterial blood pressure between two groups

| MAP at | GLT group (n=30) | ETT group (n=30) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Baseline | 92.27 | 6.74 | 92.91 | 8.88 | 0.753 |

| 1 min | 83.28 | 7.22 | 80.60 | 7.80 | 0.173 |

| 2 min | 72.49 | 6.66 | 71.87 | 6.09 | 0.707 |

| 3 min | 94.94 | 6.84 | 99.19 | 7.58 | 0.026* |

| 4 min | 97.16 | 6.63 | 101.49 | 7.48 | 0.021* |

| 5 min | 99.13 | 6.31 | 104.44 | 6.63 | 0.002* |

| 7 min | 97.86 | 6.07 | 102.42 | 5.70 | 0.004* |

| 10 min | 96.02 | 5.36 | 100.54 | 5.38 | 0.002* |

| 15 min | 93.92 | 4.47 | 98.08 | 4.62 | 0.001* |

P<0.05 considered significant. MAP=Mean arterial pressure, GLT=Gastro-laryngeal tube, ETT=Endotracheal intubation, SD=Standard deviation

Repeated ANOVA test was applied to do the intragroup comparison where the hemodynamic parameters such as HR and MAP measured over different times were independent variable and dependent variable being the subject in whom either GLT or ETT was inserted. F value was calculated. Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied for assessing the departure from sphericity. Greenhouse–Geisser test was statistically significant (P < 0.001) which implied there is a significant difference of HR, MAP between pre- and post-GLT insertion and pre- and post-ETT intubation in their respective groups [Table 5].

Table 5.

Intragroup analysis of heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure within the two groups

| Parameter | Group | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Type III Sum of Squares | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate | ETT | 14319.563 | 2.048 | 6991.124 | 372.477* | < 0.001 |

| GLT | 3138.800 | 3.448 | 910.346 | 183.076* | < 0.001 | |

| Mean arterial pressure | ETT | 29691.023 | 2.854 | 10402.139 | 432.680* | < 0.001 |

| GLT | 17910.889 | 2.281 | 7851.504 | 323.795* | < 0.001 |

*Repeated ANOVA test with Greenhouse geisser correction applied for assessing the departure from sphericity. P<0.05 considered significant.. HR=Heart rate, GLT=Gastro-laryngeal tube, ETT=Endotracheal intubation, MAP=Mean arterial pressure

The highest and lowest SpO2 recorded during the procedure, as mean (SD) was comparable between two groups (99.67 [0.48] and 98.13 [0.74] in GLT group as compared to 97.73 [0.74] and 99.90 [0.31]) in ETT group. Blood staining of the tip of the airway device was more in the patients in GLT group (20%, n = 6) as compared to patients of the ETT group (6%, n = 2) with the results not significant with P = 0.192.

DISCUSSION

ERCP is a safe tool available to evaluate pancreatic and biliary diseases, and with the advancement in the technology, it has established itself as an effective and viable therapeutic tool for the safe nonsurgical way of management of pancreatobiliary diseases. These therapeutic interventions of ERCP are highly time-consuming complex endoscopic procedures.

Unwarranted complications like hypoxemia are common during ERCP when the procedures are being done under conscious sedation (Moderate sedation). A retrospective study by Sorser et al. demonstrated a higher incidence of adverse cardiorespiratory event (6.5%) in nonintubated patients when compared with the patients with ETT (0.3%) who underwent ERCP.[11] Repeated doses of propofol for deepening the plane of sedation inadvertently slips the patient into deep sedation compromising the ventilation and oxygenation requiring definitive airway management.[12,13] Failure rate of ERCP under GA was noted to be 7% by Raymondos et al. which was unrelated to any anesthesia technique but to the endoscopy-related issues. In contrast about 14% patients under conscious sedation developed a failure of ERCP which was related to the discomfort, pain, and loss of airway patency.[14] Therefore, to obviate the unwarranted complications related to conscious sedation, a definitive airway is imperative in complex upper GI procedures, especially so in high-risk cases an endotracheal intubation is the most commonly employed technique.

Stress response to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation is well documented and may result in adverse outcome in the form of tachycardia and hypertension.[15,16,17,18] GLT has been used as a viable option for securing the airway for complex upper GI endoscopic procedures as described by Gaitini et al. and Fabbri et al. in their study.[8,19] Sreevastava et al. in their study reported the successful use of GLT in Indian patients.[20] However, stress response to GLT has not been studied till now, even though stress response to other supraglottic airways such as LMA and laryngeal tube have been documented.[7,15,21]

A study by Carron et al. compared the hemodynamic response between ETT and Proseal LMA in obese patients for bariatric surgery. Plasma norepinephrine levels as well as hemodynamic response profile was better with Proseal LMA group at insertion and removal of the device as well as in the postrecovery period.[22] Tang et al. showed that in neurosurgery patients I-gel LMA combined tracheal intubation yields a stable hemodynamics both at intubation and recovery when compared with the ETT group.[23] The intragroup group analysis of the hemodynamic response in our study did show the increase in HR and MAP from the baseline values in both the groups, respectively, but the control group (ETT) had a more sustained response till 10 min when compared with the baseline values within the groups reflecting higher catecholamine levels in ETT groups [Tables 3 and 4].[24,25] The MAP and HR on being compared between the two groups after the insertion of the respective airway device showed significant hemodynamic response in the ETT group which was similar to results of previous studies[21,24] [Tables 3 and 4]. The attenuated response to the supraglottic airway insertion could be due to avoidance of the sympathoadrenal response which is accentuated with the laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation[24] With the ETT in place, this group also consumed more propofol during the conduct of procedure as a maintenance infusion to target the BIS value between 55 and 60 [Table 1]. This issue becomes more pertinent as patients coming for the ERCP have higher incidence of comorbidities making their physiological condition more precarious and prone for adverse cardiorespiratory events.[26,27]

Mean (SD) time taken for the insertion of GLT was more than the ETT group, and this could be due to the steeper learning curve in comparison to the more familiar technique of the endotracheal intubation [Table 1]. Four patients out of 30 required reinsertion of GLT after failure of the first attempt. In the second attempt, GLT was successfully inserted in all the four patients with no change in SpO2 levels. In contrast in control group, all patients were successfully intubated in the first attempt with no evidence of desaturation. Nonethless, the stress response to GLT insertion was significantly less in spite of prolonged insertion time and there were no episodes of desaturation during insertion. Osborn et al. in their retrospective study observed that majority of ERCP at their center could be performed by LMA successfully thereby establishing its role as an alternative to ETT with shorter recovery time.[28]

Blood staining over the tip of the airway device at the time of removal was more in GLT group (20%) as compared to the ETT Group (6%) in our study and thesse included four cases, which required reinsertion of the GLT. The probable cause of blood staining could be due to injury related to the insertion technique of the GLT as well as to the pressure exerted over the soft tissue of the airway.[8] Four patients complained of sore throat in GLT group and two patients in the ETT group with the results being comparable to each other and were related to the injury to the failed first attempt of the insertion in the GLT group.

The strengths of this study were that the both the groups were comparable in terms of patient characteristics, grading of complexity of endoscopic procedures, and further none had any episodes of desaturation and airway complications.

Limitations of the study include the observer bias as blinding could not be done. The study did not include patients having height <155 cm as GLT comes only in one size tailored made for patients >155 cm in height. Recovery after the procedure was also not compared which has a direct bearing on the optimal utilization of the health resources.

CONCLUSION

Stress response to intubation is a major concern in higher grade ASA patients undergoing complex ERCP procedures. GLT, a relatively new supraglottic device was evaluated in this study for its stress response to insertion compared to endotracheal intubation. The stress response to GLT insertion was significantly less as compared to endotracheal intubation making it a safe and viable alternative to endotracheal intubation for anesthesia in the endoscopy suite, especially in higher ASA grade patients undergoing complex ERCP procedures. This will help in meeting the clinical goals of the NORA, i.e., safe conduct and early recovery at the end of the procedure.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martindale SJ. Anaesthetic considerations during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34:475–80. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethi P, Mohammed S, Bhatia PK, Gupta N. Dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for conscious sedation in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: An open-label randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2014;58:18–24. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.126782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quine MA, Bell GD, McCloy RF, Charlton JE, Devlin HB, Hopkins A, et al. Prospective audit of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in two regions of England: Safety, staffing, and sedation methods. Gut. 1995;36:462–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice Guidelines for SEDATION and analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004–17. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg E, Kuipers E, Siersema P. The burden of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) performed with the patient under conscious sedation. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2213–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Joint Royal Colleges of Anaesthetists (RCoA) and British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) Working Party, Guidance for the use of Propofol Sedation for Adult Patients Undergoing Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and other Complex upper GI Endoscopic Procedures. 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/PropofolERCP2014.pdf .

- 7.Tahir MS, Khan NA, Masood M, Yousaf M, Warris SA. Comparison of pressor responses following laryngeal mask airway vs. laryngoscopy and endotracheal tube insertion. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2008;12:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaitini LA, Lavi A, Stermer E, Charco Mora P, Pott LM, Vaida SJ, et al. Gastro-laryngeal tube for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A preliminary report. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:1114–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukhari A, Naqash I, Zargar J, Nengroo S, Mir AW. Pressor response and intraocular pressure changes following insertion of laryngeal mask airway: Comparison with tracheal tube insertion. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:473–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotton PB, Eisen G, Romagnuolo J, Vargo J, Baron T, Tarnasky P, et al. Grading the complexity of endoscopic procedures: Results of an ASGE working party. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:868–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorser SA, Fan DS, Tommolino E, Gamarra RM. SU1391 Safety of non-intubated versus intubated ERCP: A retrospective review of gastrointestinal and cardiopulmonary complications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:AB316. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wehrmann T, Kokabpick S, Lembcke B, Caspary WF, Seifert H. Efficacy and safety of intravenous propofol sedation during routine ERCP: A prospective, controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:677–83. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung M, Hofmann C, Brackertz A. Propofol versus midazolam for conscious sedation during ERCP: A randomized prospective study. Endoscopy. 2000;32:233–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raymondos K, Panning B, Bachem I, Manns MP, Piepenbrock S, Meier PN, et al. Evaluation of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography under conscious sedation and general anesthesia. Endoscopy. 2002;34:721–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharya D, Ghosh S, Chaudhuri T, Saha S. Pressor responses following insertion of laryngeal mask airway in patients with controlled hypertension: Comparison with tracheal intubation. J Indian Med Assoc. 2008;106:787–8. 790, 810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saraswat N, Kumar A, Mishra A, Gupta A, Saurabh G, Srivastava U, et al. The comparison of proseal laryngeal mask airway and endotracheal tube in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries under general anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:129–34. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamil SN, Alam M, Usmani H, Khan MM. A study of the use of laryngeal mask airway (LMA) in children and its comparison with endotracheal intubation. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:174–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahajan L, Kaur M, Gupta R, Aujla KS, Singh A, Kaur A, et al. Attenuation of the pressor responses to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation with intravenous dexmedetomidine versus magnesium sulphate under bispectral index-controlled anaesthesia: A placebo-controlled prospective randomised trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:337–43. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_1_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Cennamo V, Polifemo AM, Maimone A, Jovine E, et al. The gastro-laryngeal tube for interventional endoscopic biliopancreatic procedures in anesthetized patients. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1051–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreevastava DK, Verma RN, Verma R. Randomised controlled trial comparing gastro laryngeal tube with endotracheal intubation for airway management in patients undergoing ERCP under general anaesthesia. Med J Armed Forces India. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2018.01.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shetty AN, Shinde VS, Chaudhari LJ. A comparative study of various airway devices as regards ease of insertion and haemodynamic responses. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:134–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carron M, Veronese S, Gomiero W, Foletto M, Nitti D, Ori C, et al. Hemodynamic and hormonal stress responses to endotracheal tube and ProSeal laryngeal mask airway™ for laparoscopic gastric banding. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:309–20. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013ef31825b6a80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang C, Chai X, Kang F, Huang X, Hou T, Tang F, et al. I-gel laryngeal mask airway combined with tracheal intubation attenuate systemic stress response in patients undergoing posterior fossa surgery. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:965925. doi: 10.1155/2015/965925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shribman AJ, Smith G, Achola KJ. Cardiovascular and catecholamine responses to laryngoscopy with and without tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:295–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell WJ, Morris RG, Frewin DB, Drew SE. Changes in plasma catecholamine concentrations during endotracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1981;53:837–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/53.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berzin TM, Sanaka S, Barnett SR, Sundar E, Sepe PS, Jakubowski M, et al. A prospective assessment of sedation-related adverse events and patient and endoscopist satisfaction in ERCP with anesthesiologist-administered sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:710–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garewal D, Vele L, Waikar P. Anaesthetic considerations for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography procedures. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26:475–80. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283620139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osborn IP, Cohen J, Soper RJ, Roth LA. Laryngeal mask airway – A novel method of airway protection during ERCP: Comparison with endotracheal intubation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:122–8. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]