Abstract

Background:

Clonidine, an alpha2 agonist, when added to local anesthetics in different regional and neuraxial blocks reduces the onset time, improves the efficacy, and increases the duration of postoperative analgesia.

Aims:

This study evaluated the effect of bupivacaine clonidine combination in ultrasound and nerve locator-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries.

Settings and Design:

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study carried out in a tertiary care center in South India on 50 patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classes I and II undergoing elective upper limb surgery under supraclavicular brachial plexus block.

Materials and Methods:

Eligible participants were randomized equally to either Group B who received 20 ml of bupivacaine and 7 mL of 2% lignocaine or Group C who received 20 ml of bupivacaine, 7 ml of 2% lignocaine, and 100 μg of clonidine.

Statistical Analysis:

Continuous outcome variables were tested for statistical significance using Student's t-test, and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for outcomes that were nonnormally distributed. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test. P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results:

The onset of sensory and motor blockade was significantly faster (P < 0.05) in Group C compared to Group B. The duration of sensory and motor block and the duration of analgesia were significantly longer in Group C (P < 0.001). The sedation in Group C patients was significantly more (P < 0.05) when compared to Group B, but none of the sedation scores exceeded 3 on the Ramsay sedation score. Hemodynamic parameters did not differ between groups (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

The inclusion of 100 μg of clonidine with bupivacaine in ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks prolongs both sensory and motor blockade. It also provides significant postoperative analgesia and mild sedation which is beneficial in the immediate stressful postoperative period.

Keywords: Brachial plexus, clonidine, local anesthetics

INTRODUCTION

The supraclavicular block of the brachial plexus is a useful alternative to general anesthesia for upper limb surgeries as they provide reliable and ideal operating conditions by maintaining stable hemodynamics, superior analgesia, and muscle relaxation. The sympathetic block it provides reduces the postoperative pain, vasospasm, and edema. The acceptance of regional anesthesia techniques has been limited by two significant factors, namely, the slow onset time and the short duration of action. Many a time, the duration of surgery outlasts the effective analgesic period of the regional technique employed thus requiring the conversion to a general anesthetic. Furthermore, the role of peripheral nerve blocks is not anymore limited to the intraoperative period alone but is inclusive of postoperative pain and chronic pain management.

However, the duration of analgesia after single injection nerve blocks may not be sufficient for a comfortable transition to oral analgesics in postoperative period.[1] The advantages of effective postoperative pain management include patient comfort and satisfaction, earlier mobilization, fewer pulmonary and cardiac complications, reduced risk of deep vein thrombosis, faster recovery with less likelihood of developing neuropathic pain, and reduced expenses.

Initially, several attempts were made to combine short rapid acting local anesthetic agents like lignocaine with longer acting agents such as bupivacaine with late onset to make up for the pitfalls such as late onset and inadequate duration of action. From this stemmed the issue of cumulative toxicity of local anesthetics and decreased efficacy due to concentration dilution. Certain drugs such as neostigmine, opioids, hyaluronidase, and midazolam have been used as adjuncts to local anesthetics to lower the dose of each agent and enhance the efficacy of the blockade while reducing the incidence of adverse effects of each of the agents.[2,3,4] Tramadol and fentanyl also have been successfully used as adjuvants to local anesthetics in brachial plexus block.[5,6]

Since the 1980s, clonidine, an alpha2 (α2) adrenergic agonist with some α1 adrenergic properties, has been used as an adjuvant to local anesthetics in various regional anesthesia techniques to extend the duration of blockade.[5] It has been proved that clonidine improves the quality and the duration of the local anesthetic nerve blocks as well as in spinal and epidural anesthesia.[1,6,7,8,9] This property has been attributed to the fact that α2 adrenergic agonists enhance the nerve block of local anesthetics by facilitation of C fiber blockade, by local vasoconstriction or by spinal action caused by diffusion along the nerve or retrograde axonal transport.[10] Furthermore, clonidine enhances the action of local anesthetics by blocking the sodium channels and opening the potassium channels resulting in membrane hyperpolarization.[11] This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of clonidine used along with bupivacaine in a supraclavicular brachial plexus block on the duration of action, the quality of sensory and motor blockade, duration of postoperative analgesia and intra- and post-operative complications in ultrasound and nerve locator-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized, prospective double-blinded study was commenced after obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional or regional) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 that was revised in 2000. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in their regional language. Fifty, patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classes I and II, aged between 20 and 60 years of both genders undergoing surgical procedures of forearm or hand under supraclavicular brachial plexus block were recruited. Patients with significant history of neurological, psychiatric and neuromuscular diseases, alcohol and or drug abuse, diabetes mellitus, renal disorders, other contraindications for a supraclavicular block such as local infection at the site, bleeding disorders/anticoagulant therapy, and patient refusal were excluded from the study. The principal investigator discussed the details of the study with the patient on the night before the surgery, and written consent was obtained.

Computer-generated block randomization was done. Opaque sealed envelopes with the randomly assigned group either Group B who received 20 ml of bupivacaine and 7 ml of 2% lignocaine or Group C who received 20 ml of bupivacaine and 7 ml of 2% lignocaine along with 100 μg of clonidine was opened by one of the investigators just before the administration of the block. The anesthetist who made the observations was blind to the test drug/combination administered.

All patients were kept fasting as per standard guidelines, and aspiration prophylaxis was administered. Anxiolytic premedication was avoided due to the possible interference with the assessment of sedation. Group B received 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 7 ml of 2% lignocaine. Group C received 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 7 ml of 2% lignocaine with 100 μg of clonidine. On the day of surgery, standard monitors as per ASA guidelines were connected, and an intravenous (IV) cannula was secured in the nonoperative limb once the patient arrived in the premedication room. The patient was positioned supine with head turned away from the limb to be operated. The injection site was cleaned with chlorhexidine and was draped. A high-frequency adult linear ultrasound probe covered with sterile ultrasound probe cover was then placed over the supraclavicular region. The brachial plexus was identified in relation to the pulsating subclavian artery and the hyperechoic first rib. Local anesthesia at the injection site was provided with 2 ml 2% plain lignocaine. The plexus was then approached using an in-plane technique with a 5-cm sterile 22G short-beveled insulated (Teflon – coated) nerve-stimulating needle. Once the needle tip reached the nerve sheath, stimulation frequency was set at 2 Hz and gradually reduced to <0.5 Hz after which following negative aspiration for blood/air drug was deposited at the angle between subclavian artery and first rib and outside the nerve sheath.

All observations were performed by a doctor, who was blinded as to which group the patient was assigned. Vital parameters of the patient including the heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored. The degree of sensory and motor block was assessed at 5, 10, 20, 30 min after the block and later at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h as well. The duration of postoperative analgesia was recorded as the time to which the patient asks for the first dose of rescue analgesia. The sensory block was evaluated by pinprick on skin dermatomes C4 to T2 whereas motor block was assessed by asking the patient to adduct the shoulder and flex the forearm against gravity.

The sensory score was graded by pinprick as:

0- Sharp pain

1- Touch sensation only

2- No sensation

And the motor block was graded by the Bromage scale as:

0- Normal motor function

1- Decreased motor strength with ability to move the fingers only

2- Complete motor block with inability to move the fingers.

The onset of sensory block was defined as the time elapsed between injection of the drug and complete loss of cold perception in hand, while the onset of motor blockade was defined as the time elapsed from injection of the drug to complete motor block. Duration of sensory block (the time elapsed between injection of drug and appearance of pain requiring analgesia) and duration of motor block (the time elapsed between injection of the drug and complete return of muscle power) were recorded.

The Ramsay Sedation Score (shown below) of all patients at 5, 10, 20, 30 min and at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h were documented after the block.

Ramsay sedation Score:

Anxious and agitated or restless or both

Cooperative, oriented, and tranquil

Responding to commands only

Brisk response to light glabellar tap

Sluggish response to light glabellar tap

No response to light glabellar tap.

Both the groups were compared for any difference in demographics such as weight, age, sex distribution, and time of onset of sensory and motor blockade, duration of sensory and motor blockade, duration of analgesia, and sedation scores in the postoperative period.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 18, Chicago, IL, USA). Baseline parametric variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as percentages (%). Continuous outcome variables were tested for statistical significance using a Student's t-test (two-tailed, independent), and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for outcomes that were nonnormally distributed. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

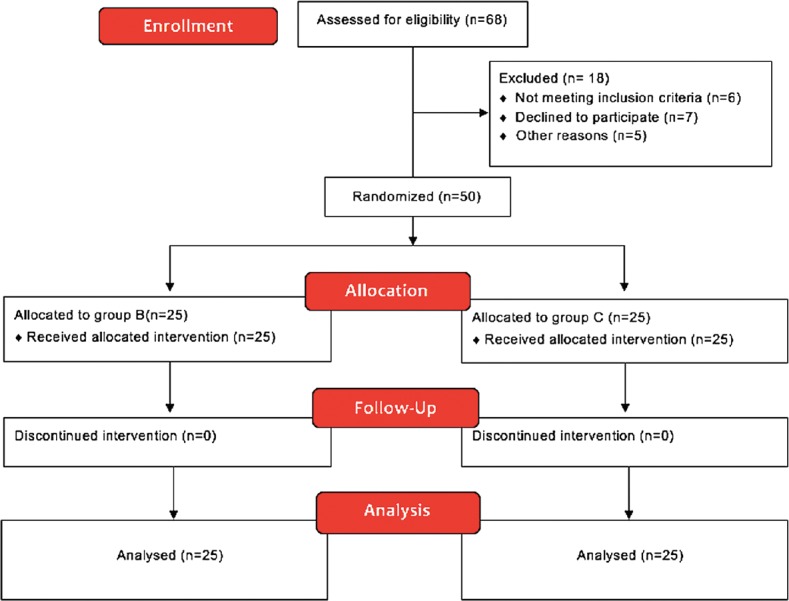

The recruitment and follow-up is detailed in Figure 1. Demographic data (age, weight, and gender) and the ASA status of patients were comparable between Group B and Group C [Table 1]. Furthermore, the mean (±SD) duration of surgery was similar in all the groups [Table 2]. In our study, we found that the onset of sensory blockade was slightly earlier in the study group of clonidine (Group C) having a mean onset time of 6.60 ± 2.38 min in comparison with the control group (Group B) having a mean onset time of 8.20 ± 2.84 min. The statistical analysis by Student's unpaired t-test was found to be statistically significant as P value was 0.036 (P < 0.05). Furthermore, we observed that the mean onset time of motor block was earlier in the study group (Group C) having a mean onset time of 9.60 ± 2.85 min when compared to the mean onset time in the control group (Group B) being 14.60 ± 3.76 min. This enhancement in the onset time was found to be significant by unpaired t-test with P < 0.001 [Table 3]. The duration of sensory and motor blockade in Group C was significantly longer than in Group B. A similar pattern was observed when the time to rescue analgesia was compared between the two groups [Table 4].

Figure 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the study

Table 1.

The patient characteristics of the two groups

| Patient characteristics | Group B (n=25) | Group C (n=25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 37.28±9.45 | 41.20±8.81 | 0.14 |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 58.8±5.98 | 57.16±5.46 | 0.32 |

| Gender (male/female) | 20/5 | 17/8 | 0.33 |

| ASA physical status classes (I/II) | 18/25 | 20/25 | 0.63 |

ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists, SD=Standard deviation

Table 2.

The total surgical duration in both the groups

| Duration | Group B (n=25) | Group C (n=25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (min) | 180.80±43.77 | 172.00±46.90 | 0.5 |

Table 3.

The time onset of sensory and motor block in both the groups

| Time of onset of block | Group B (n=25) | Group C (n=25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of sensory onset (min), mean±SD | 8.20±2.84 | 6.60±2.38 | 0.036 |

| Time of motor onset (min), mean±SD | 14.60±3.76 | 9.60±2.85 | <0.001 |

SD=Standard deviation

Table 4.

The total duration of sensory and motor blockade and time elapsed till the demand of first rescue analgesic in both the groups

| Time duration (h) | Group B (n=25) | Group C (n=25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total duration of sensory blockade (h), mean±SD | 5.51±1.02 | 9.63±1.15 | <0.001 |

| Total duration of motor blockade (h), mean±SD | 4.96±0.86 | 8.54±1.39 | <0.001 |

| Time elapsed till the demand of first dose of rescue analgesia (h), mean±SD | 5.89±0.86 | 9.90±1.19 | <0.001 |

SD=Standard deviation

It was observed that in Group B, all patients were awake and alert and had a sedation score of 1. While, in Group C, 20% of patients at the 15-min time point, 32% of patients at the 20-min time point, and 32% of patients at the 30-min had a sedation score of 2. None of the patients had a sedation score of 3 and above during the study period. Statistical analysis of sedation score by Chi-square test showed that the difference in sedation score was significant (P < 0.05). Although the sedation scores were significantly different, the hemodynamic variables of HR, systolic BP, diastolic BP, and oxygen saturation at all time points were comparable between the two groups. None of the patients was noticed to have any neurological deficits on postoperative follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Many trials have come in the past with the use of clonidine as an adjuvant to local anesthetics in peripheral nerve blocks. Many of them found that although the onset of the block was faster with clonidine, most of the patients had higher incidence of systemic adverse effects such as bradycardia, hypotension, and excessive sedation. To overcome this, we used an ultrasound and nerve locator-guided brachial plexus that allowed the deposition of the entire volume under the sheath which helped in achieving a higher concentration at the site. This also would reduce the incidence of systemic adverse events. Studies have also shown that dexmedetomidine added to levobupivacaine for axillary brachial plexus block shortens the onset time and prolongs the duration of the block and the duration of postoperative analgesia. However, they concluded that dexmedetomidine also may lead to bradycardia.[12,13,14,15,16]

In this study, we found that the mean onset of sensory blockade was faster in both the groups when compared to trials by other investigators. The shorter onset of time in both the groups in this study may be attributed to the faster onset of action of lignocaine, the larger volume of the local anesthetic solution as well as the use of the ultrasound as a guide along with the nerve locator. The clonidine group had a faster onset by 1.6 min as compared to the other Group B. This concurs with the study by Iohom et al. where the mean onset time of sensory block was much faster in the clonidine group by 3.4 min as compared to that of the placebo.[17] The meta-analysis conducted by Pöpping et al. of various studies using clonidine in brachial plexus block also reinforces the fact that the clonidine group has an early onset of sensory block time.[6] In our study, we observed a significant enhancement in the mean motor onset time in the clonidine group as compared to the control group. The faster onset of the motor blockade could be due to the local effect of clonidine in the ionic channels of the nerve and a synergistic action with that of local anesthetic agents.[18,19] Chakraborty et al. also reported an earlier onset of the motor blockade in clonidine group by 8 min over the control group. This fact was further reinforced by our study as well.

We also found that there was no significant time interval between the onset of the sensory blockade and motor blockade. First, this could be due to the somatotopic arrangement of the fibers in the nerve bundle at the level of trunks in which motor fibers are located more peripherally than sensory fibers. Second, our technique aided in achieving a higher drug concentration at the target site with minimal extravasation of the blocking solution outside the fascial sheath. Our study showed a significantly longer mean duration of sensory blockade for the clonidine group as compared to the control group. Hence, the local anesthetic began to block motor fibers before it arrived at the centrally located sensory fibers thereby reducing the time interval between the sensory and motor blockade.[20]

In our study, we observed a significant prolongation in the mean duration of analgesia in the clonidine group than in the control group. McCartney et al. found that clonidine as an adjunct to bupivacaine prolonged the postoperative analgesic effects compared to bupivacaine alone when administered for various peripheral nerve blocks.[21] Studies done by Pöpping et al. and Eledjam et al. showed that the difference in the duration of postoperative analgesia for the clonidine group was significantly higher in contrast to that of the control group.[1,6] This prolongation in the duration of the blockade has attributed the interaction between clonidine and the axonal ion channel and receptors.[18,22] The mechanism of action of this blockade was due to the action of clonidine inhibiting the action potential of A and C fibers in peripheral nerves.[23,24,25] This study showed that there was a significant prolongation of the mean duration of the motor blockade in the clonidine group as compared to the control group. Pöpping et al. in their study showed that there was a significant prolongation of the average duration of motor blockade by 141 min in the clonidine when compared to that of the control group.[6] Cucchiaro and Ganesh further concurred with this.[7] In contrast, Duma et al. showed that there was no added advantage regarding the duration of blockade between the clonidine and placebo group.[5] This was probably because clonidine, when used as an adjunct with longer acting local anesthetic agents like levobupivacaine and bupivacaine, may not exhibit a predictable response.[5]

None of the patients in our study group had significant hemodynamic changes from the baseline recording. Even though some patients had a minimal decrease in systolic, diastolic as well as the mean arterial pressure, all of them maintained their hemodynamic parameters within the normal range. The reasons for this being the effective analgesia provided by clonidine so also the minimal sedation found with this group. It is shown that IV, centrineuraxial administration of clonidine resulted in significant hemodynamic variations including bradycardia, hypotension, and sedation. Such variations were not encountered in our study group which is attributed to the fact that there is a minimal chance of the drug attaining its peak plasma concentration due to the poor vascularity present at the site of injection as well as the low drug concentration and also the ultrasound and nerve locator aided in preventing accidental intravascular injection.

Intraoperative sedation scores were higher in the clonidine group when compared with the control group but were not statistically significant. The highest score in the clonidine group had a sedation score of 2, and no patient had a sedation score of 3 or more which required airway maintenance. This observation may be bias induced, as individuals were scored even during their natural sleep hours during the study. This mild sedative effect of clonidine relives surgery-related anxiety and provides much-needed comfort for the postoperative patient as the postoperative period is a stressful period. This minimal sedative effect which did not result in any adverse events such as respiratory compromise should, therefore, be considered as a beneficial effect of clonidine.

The use of ultrasound and nerve locator allowed the deposition of the entire volume under the sheath which helped in achieving a higher concentration at the site. This in turn would have resulted in the faster onset, no significant interval between the onset of sensory and motor blockade, longer duration of sensory blockade, and lesser systemic adverse events compared to studies done by other investigators.

CONCLUSION

Based on this study, we would like to conclude that inclusion of 100 μg of clonidine with bupivacaine in ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks prolongs both sensory and motor blockade. It also provides significant postoperative analgesia and mild sedation which is beneficial in the immediate stressful postoperative period.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.YaDeau JT, LaSala VR, Paroli L, Kahn RL, Jules-Elysée KM, Levine DS, et al. Clonidine and analgesic duration after popliteal fossa nerve blockade: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1916–20. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fe44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazin JE, Massoni C, Bruelle P, Fenies V, Groslier D, Schoeffler P, et al. The addition of opioids to local anaesthetics in brachial plexus block: The comparative effects of morphine, buprenorphine and sufentanil. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:858–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.174-az0311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bone HG, Van Aken H, Booke M, Bürkle H. Enhancement of axillary brachial plexus block anesthesia by coadministration of neostigmine. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24:405–10. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(99)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keeler JF, Simpson KH, Ellis FR, Kay SP. Effect of addition of hyaluronidase to bupivacaine during axillary brachial plexus block. Br J Anaesth. 1992;68:68–71. doi: 10.1093/bja/68.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duma A, Urbanek B, Sitzwohl C, Kreiger A, Zimpfer M, Kapral S, et al. Clonidine as an adjuvant to local anaesthetic axillary brachial plexus block: A randomized, controlled study. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:112–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pöpping DM, Elia N, Marret E, Wenk M, Tramèr MR. Clonidine as an adjuvant to local anesthetics for peripheral nerve and plexus blocks: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:406–15. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cucchiaro G, Ganesh A. The effects of clonidine on postoperative analgesia after peripheral nerve blockade in children. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:532–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000253548.97479.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iskandar H, Benard A, Ruel-Raymond J, Cochard G, Manaud B. The analgesic effect of interscalene block using clonidine as an analgesic for shoulder arthroscopy. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:260–2. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200301000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutschala D, Mascher H, Schmetterer L, Klimscha W, Fleck T, Eichler HG, et al. Clonidine added to bupivacaine enhances and prolongs analgesia after brachial plexus block via a local mechanism in healthy volunteers. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2004;21:198–204. doi: 10.1017/s0265021504003060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marhofer D, Kettner SC, Marhofer P, Pils S, Weber M, Zeitlinger M, et al. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine prolongs peripheral nerve block: A volunteer study. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:438–42. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Wang CS, Shi JH, Sun B, Liu SJ, Li P, et al. Perineural administration of dexmedetomidine in combination with ropivacaine prolongs axillary brachial plexus block. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:680–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathuria S, Gupta S, Dhawan I. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Saudi J Anaesth. 2015;9:148–54. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.152841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esmaoglu A, Yegenoglu F, Akin A, Turk CY. Dexmedetomidine added to levobupivacaine prolongs axillary brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1548–51. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fa3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghoshmaulik S, Bisui B, Saha D, Swaika S, Ghosh AK. Clonidine as an adjuvant in axillary brachial plexus block for below elbow orthopedic surgeries: A comparison between local and systemic administration. Anesth Essays Res. 2012;6:184–8. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.108307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarbo K, Batra YK, Panda NB. Brachial plexus block with midazolam and bupivacaine improves analgesia. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:822–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03021776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brockway MS, Winter AW, Wildsmith JA. Prolonged brachial plexus block with 0.42% bupivacaine. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:604–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/63.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iohom G, Machmachi A, Diarra DP, Khatouf M, Boileau S, Dap F, et al. The effects of clonidine added to mepivacaine for paronychia surgery under axillary brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1179–83. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000145239.17477.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaumann DM, Brunet PC, Jirounek P. Clonidine enhances the effects of lidocaine on C-fiber action potential. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:719–25. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenach JC, De Kock M, Klimscha W. Alpha(2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984-1995) Anesthesiology. 1996;85:655–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winnie AP, Tay CH, Patel KP, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z. Pharmacokinetics of local anesthetics during plexus blocks. Anesth Analg. 1977;56:852–61. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197711000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCartney CJ, Duggan E, Apatu E. Should we add clonidine to local anesthetic for peripheral nerve blockade? A qualitative systematic review of the literature. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eledjam JJ, Deschodt J, Viel EJ, Lubrano JF, Charavel P, d’Athis F, et al. Brachial plexus block with bupivacaine: Effects of added alpha-adrenergic agonists: Comparison between clonidine and epinephrine. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:870–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03036962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butterworth JF, 4th, Strichartz GR. Molecular mechanisms of local anesthesia: A review. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:711–34. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199004000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasir D, Gasanova I, Drummond S, Alexander J, Howard J, Melikman E, et al. Clonidine, but not dexamethasone, prolongs ropivacaine-induced supraclavicular brachial plexus nerve block duration. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2017;12:92–8. doi: 10.2174/1574884712666170605085508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saied NN, Gupta RK, Saffour L, Helwani MA. Dexamethasone and clonidine, but not epinephrine, prolong duration of ropivacaine brachial plexus blocks, cross-sectional analysis in outpatient surgery setting. Pain Med. 2017;18:2013–26. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]