Abstract

Background:

There are several methods employed in the management of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy such as conventional systemic analgesics, including paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic opioids, and thoracic epidural analgesia with all having its limitations and side effects.

Aims:

The present study aims to compare ultrasound-guided subcostal transversus abdominis (STA) block with intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine in reducing postoperative pain, total analgesic consumption, nausea and vomiting, and recovery time in patients after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Settings and Design:

A prospective study was conducted between January 2017 and December 2017 in 80 patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy after approval of the Institutional Ethical Committee (Reference No: SGRR/IEC/05/16).

Materials and Methods:

Patients were randomly divided into two equal-sized (n = 40) study groups. Group 1 patients received ultrasonography-guided STA block with 0.25% levobupivacaine both sides and Group 2 patients received 0.25% levobupivacaine through intraperitoneal route.

Statistical Analysis:

Quantitative data were expressed in mean and standard deviation. Qualitative data were expressed in proportion and percentages. Independent t-test was applied to compare the means of quantitative data and the Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Survival curve was drawn using the log-rank test for comparing two groups.

Results:

Patient characteristics regarding age, gender, and weight were comparable in the two groups. The mean Numerical Rating Scale scores were less in Group 1 than in Group 2 in the first 6 h, which was found to be statistically significant. There was no significant difference noted in pain scores after 6 h up to 24 h in postoperative area among the two groups. Pain scores for shoulder tip pain were lower in Group 2 as compared to Group 1 in the first 24 h, which was not significant statistically.

Conclusion:

STA block is a better modality for analgesia compared to intraperitoneal instillation in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Intraperitoneal levobupivacaine, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Numerical Rating Scale, subcostal transversus abdominis block, ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is very commonly performed nowadays, and it has now completely replaced open cholecystectomy in the management of biliary lithiasis. Although it is minimally invasive surgery, pain in postoperative period is always major concern as it increases perioperative stress, morbidity, and hospital stay.[1,2,3]

There are two components involved in pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the visceral component is due to tissue damage in anterior abdominal wall during the insertion of trocar by surgeons and in around 50% of patients complain of shoulder tip pain due to diaphragmatic irritation caused by spillage of blood or bile and peritoneum stretching caused by pneumoperitoneum.

There are several methods employed in the management of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy such as conventional systemic analgesics, including paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic opioids, thoracic epidural analgesia, low-pressure pneumoperitoneum, and warm air with all having its limitations and side effects.

In the present study, we have compared ultrasound-guided subcostal transversus abdominis (STA) block with intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine in reducing postoperative pain, total analgesic consumption, nausea, vomiting, and recovery time in patients after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We started this prospective study after approval from the Ethical Committee of our Institute. The study was done from January 2017 to December 2017. It was carried out in 80 American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) physical status Classes I and II of either sex aged between 20-60 years posted for elective laproscopic cholecystectomy. Exclusion criteria were patient refusal, hypersensitivity or allergic to local anesthetics, already on pain medication for chronic pain, morbidly obese patients, or if the patient is unable to inform about their pain scores due to psychological reasons.

Patients were randomly divided into two equal-sized (n = 40) study groups. Group 1 patients received ultrasonography (USG)-guided STA block with 0.25% levobupivacaine both sides, and Group 2 patients received 0.25% levobupivacaine through the intraperitoneal route.

Six patients were withdrawn from the study due to difficult anatomy, common bile duct stones, or excessive bleeding and similar number of patients were added to keep 40 patients in each group. All patients were educated about the standard Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) pain score of 0–10, during visit in preanesthetic checkup clinic.

On arrival to the operation theater, intravenous line was established with 18G cannula and standard ASA recommended monitoring was done with 5-lead electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, finger pulse oximetry, and end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) in all patients.

A standardized general anesthetic regime was employed in all patients, consisting of propofol 2–3 mg/kg, fentanyl 2 μg/kg, and vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg, and intraoperative anesthesia was maintained with 70% nitrous oxide, 30% oxygen, and 1% isoflurane.

At the end of surgery, all patients were given analgesia with paracetamol 15 mg/kg and neuromuscular block was reversed with standard doses of neostigmine and glycopyrrolate.

For Group 1, the STA block was given under ultrasound guidance; the probe was placed below the xiphisternum and moved laterally along the subcostal margin to the anterior axillary line. A 100-mm, 22G block needle was then guided, just inferior to the right costal margin at the anterior axillary line such that the tip lay between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscle within the neurovascular plane. Following aspiration, a volume of 20 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine was injected, and the same procedure was repeated on the other side.

After ascertaining patient's eligibility, STA block was given by the same trained anesthesiologist in Group 1 and intraperitoneal levobupivacaine in Group 2 in all the study patients. Data were collected in postanesthesia care unit by another anesthesiologist who did not know which patient has received STA block or intraperitoneal instillation.

For Group 2, at the end of surgery and before the removal of trocars, 40 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine diluted in normal saline was instilled by the surgeon intraperitoneally at gallbladder bed and under domes of both diaphragms under direct vision. The pressure of the gas insufflation was kept within 10–12 mm Hg in all patients. At the end of surgery, CO2 was evacuated, and intraperitoneal anesthetic solution was left in situ.

The intensity of postoperative pain was recorded on a NRS of 0–10 (0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible) at rest and during movement (pain intensity was measured 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h) after surgery. The severity of shoulder tip pain was also recorded in all patients on NRS.

The time of the first analgesic demand was recorded and also total doses of rescue analgesia in the form of bolus of 1 mg/kg tramadol intravenously in the first 24 h to achieve pain score <4 were recorded.

All patients were discharged from the recovery unit when patients were pain free, hemodynamically stable, absence of nausea, and vomiting achieving modified Aldrete score of ≥9.

Data analysis

The data collected from 80 participants were entered into Microsoft Excel version 2016. Quantitative data were expressed in mean and standard deviation. Qualitative data were expressed in proportion and percentages. Independent t-test was applied to compare the means of quantitative data, and the Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Graphs were formed using Excel software while survival analysis curve was drawn using SPSS software version 23. Survival curve was drawn using the log-rank test for comparing two groups.

RESULTS

A total of 80 patients enrolled in the study. Group 1 (n = 40) patients received USG-guided STA block and Group 2 (n = 40) patients received intraperitoneal 40 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine.

Patient characteristics regarding age, gender, and weight were comparable in the two groups. There was no significant difference between the groups regarding the duration of anesthesia and surgery as well [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Group 1 | Group 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD | 42±9.4 | 44±8.6 |

| Sex, female:male | 29:11 | 26:14 |

| Weight, mean±SD | 55±10.6 | 57±9.6 |

| Duration of surgery, mean±SD | 53±16.7 | 55±16.2 |

SD=Standard deviation

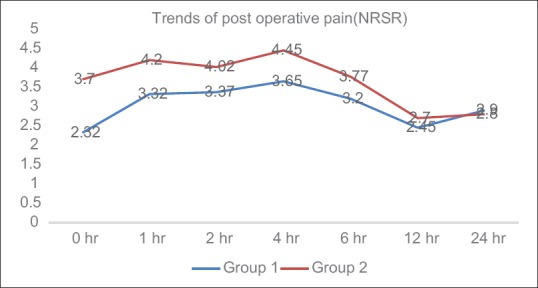

The mean numerical rating score for pain at rest was less in Group 1 than in Group 2 in the first 6 h, which was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.002). There was no significant difference noted in pain scores after 6 h up to 24 h in the postoperative area among the two groups (P = 0.72) [Figure 1 and Table 2].

Figure 1.

Numerical rating score for pain at rest scores at immediate postoperative period, at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h

Table 2.

Numerical Rating Scale score at rest postoperatively

| NRSR (h) | Mean±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | ||

| 0 | 2.32±0.82 | 3.7±1.5 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 3.32±1.09 | 4.2±1.39 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 3.37±1.29 | 4.02±1.38 | 0.03 |

| 4 | 3.65±1.14 | 4.45±1.17 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 3.2±1.09 | 3.77±1.25 | 0.03 |

| 12 | 2.45±1.13 | 2.70±1.13 | 0.32 |

| 24 | 2.9±1.51 | 2.8±1.50 | 0.76 |

NRSR: Numerical rating scale at rest for pain, SD=Standard deviation

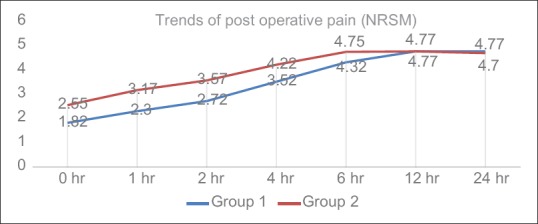

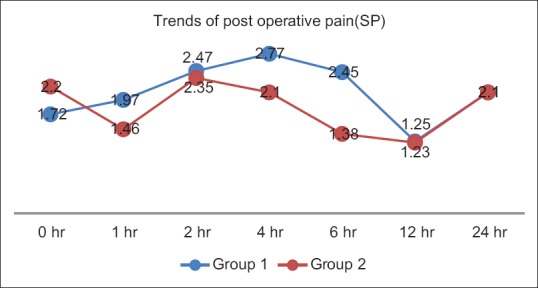

The mean numerical rating score for pain at movement was less in the Group 1 than in the Group 2 in the first 6 h, which was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.03). There was no significant difference noted in pain scores during movement after 6 h up to 24 h in postoperative area among the two groups (P = 0.85) [Figure 2 and Table 3]. Pain scores for shoulder tip pain were lower in Group 2 as compared to Group 1 in the first 24 h but were not statistically significant (P = 0.23) [Figure 3 and Table 4].

Figure 2.

Numerical rating score for pain at movement scores at different time intervals

Table 3.

Numerical Rating Scale scores at movement postoperatively

| NRSM (h) | Mean±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | ||

| 0 | 1.82 (0.74) | 2.55 (1.46) | 0.00 |

| 1 | 2.3 (0.72) | 3.17 (1.69) | 0.00 |

| 2 | 2.72 (1.03) | 3.57 (1.87) | 0.01 |

| 4 | 3.52 (0.9) | 4.22 (1.45) | 0.01 |

| 6 | 4.32 (0.97) | 4.75 (1.21) | 0.08 |

| 12 | 4.77 (1.07) | 4.77 (1.07) | 1 |

| 24 | 4.77 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.36) | 0.8 |

NRSM=Numerical Rating score for pain at movement, SD=Standard deviation

Figure 3.

Shoulder pain at different time intervals

Table 4.

Numerical Rating Scale shoulder pain scores postoperatively

| SP (h) | Mean±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | ||

| 0 | 1.72 (0.67) | 2.2 (2.04) | 0.16 |

| 1 | 1.97 (0.8) | 1.46 (1.48) | 0.05 |

| 2 | 2.47 (0.8) | 2.35 (2.27) | 0.76 |

| 4 | 2.77 (1.4) | 2.1 (2.02) | 0.09 |

| 6 | 2.45 (1.41) | 1.38 (1.48) | 0.00 |

| 12 | 1.25 (1.55) | 1.23 (1.54) | 0.94 |

| 24 | 2.1 (2.21) | 2.1 (2.22) | 1 |

SP=Shoulder pain, SD=Standard deviation

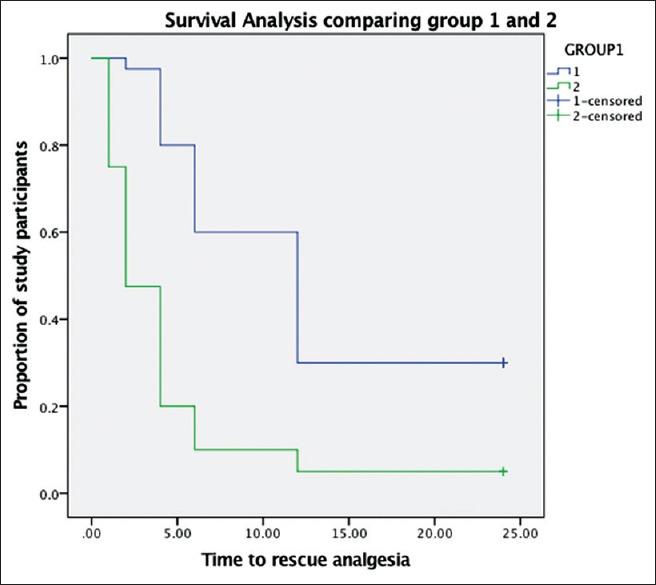

The Kaplan–Meier survival plot for time to first analgesic request is shown in Figure 4. The time to first analgesic request in Group 1 was 4.3 (1.12) h, compared with 2.1 (0.57) h in Group 2. This resulted in lower dose of total dose consumption of rescue analgesia in Group 1. Total consumption of rescue analgesics was found to be higher in Group 2 as compared to Group 1. When total analgesia consumption in 24 h was analyzed, Group 1 had total and mean of 82.25 mg (24.13) and Group 2 had total and mean 96.25 mg (25.3) of tramadol consumption which was not statistically significant (P = 0.12).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival plot for time to first analgesic request

Incidence of nausea and vomiting and use of antiemetics were found to be similar in both groups. In this study, we have used prophylactic antiemetic intraoperatively and found the incidence, and the severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting was similar in both groups.

Postoperative nausea was assessed on four-point scale (0-none, 1-mild, 2-moderate, and 3-severe). Two patients in Group 1 had nausea (Grade 1 in one patient and Grade 2 in second patient), whereas four patients in Group 2 (three patients had Grade 2 and one patient had Grade 3) complained of nausea. One patient had vomiting in Group 1 whereas two patients had in Group 2. The difference was not statistically significant. Injection metoclopramide 10 mg intravenously was administered when the patient had nausea score 2 or more or had vomiting. In Group 1, three patients required metoclopramide whereas in Group 2, four patients required rescue medication.

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is very commonly performed elective outpatient procedures nowadays, and appropriate management of postoperative pain improves patient satisfaction, decrease opioid consumption, early recovery, and discharge after the procedure.[4]

In the present study, we have compared the analgesic efficacy of STA block with intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetic in 80 patients posted for elective laparoscopic who were randomly divided into two groups of 40 each.

The transversus abdominis block is a relatively new technique in the management of postoperative pain after abdominal surgeries by injecting local anesthetic and blocking the sensory nerves in the layers of anterior abdominal wall.[5] In this study, we have used ultrasound to guide our block as there are high chances of inadvertent intraperitoneal injection and visceral damage-related complications in blind technique.[6,7]

In various studies, laparoscopic cholecystectomy and other abdominal surgeries demonstrated reduced pain scores and opioid consumption after transversus abdominis block.[8,9,10]

In a study done by Joris et al.[11] found no change in pain scores and opioid consumptions in patients instilled with 80 mL of bupivacaine 0.125% with epinephrine 1/200,000 intraperitoneally after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and this is contrary to our study where we demonstrated reduced pain scores after intraperitoneal injection of local anesthetic.

Our study has shown similar results with Alexander[12] where there were reduced opiate and oral analgesic requirements in patients administered 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine intraperitoneal injection after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

A study in 2009 compared USG-guided transverse abdominis block with 0.5% bupivacaine to conventional analgesics for 24-h postoperatively after laparoscopic cholecystectomy found more requirement of sufentanil intraoperatively and morphine postoperatively in control group.[9]

In this study, we compared the postoperative analgesic effect of levobupivacaine when used as an IP and that of STA block. We found significant differences between the NRS scores of the STA group and the IP group immediately postoperatively and for the following 6 h postoperatively. The difference in NRS scores was nonsignificant in the subsequent measurements in the first 24 h.

Our study has shown similar results with a study of Tolchard et al.[13] who demonstrated better pain scores and reduced opioid consumption in the first 4 h in STA group when compared with port-site infiltration of local anesthetic.

A study done by Gupta et al.[14] has shown conflicting results to our study, where intraperitoneal instillation of fentanyl 100 μg along with bupivacaine 0.5%, 20 ml significantly reduced intensity of postoperative pain even after 24 h, and pain scores were lower throughout in IP group as compared to STA patients.

After laparoscopic cholecystectomy, around 50% of patients complain of shoulder tip pain which may be due to diaphragmatic irritation caused by spillage of blood or bile and peritoneum stretching caused by pneumoperitoneum consistent to our observation in our study. Other studies have also shown similar results that IP injection of local anesthetics is beneficial in reducing postoperative shoulder pain after laparoscopic surgery.[15,16]

In this study, there was lower postoperative rescue analgesic requirement in STA group as compared to patients in IP (P < 0.05) group with significantly longer time for the first dose of rescue analgesia required and this is consistent with the results of Fredrickson and Seal.[17]

CONCLUSION

In this study, statistical analysis proved that transversus abdominis block group had lower pain scores and less analgesic requirements in the first 6 h as compared to intraperitoneal group, but shoulder pain was less in local port instillation group but was not statistically significant.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ji W, Li LT, Li JS. Role of laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in the treatment of complicated cholecystitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:584–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1999;44:187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berggren U, Gordh T, Grama D, Haglund U, Rastad J, Arvidsson D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: Hospitalization, sick leave, analgesia and trauma responses. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1362–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu CL, Rowlingson AJ, Partin AW, Kalish MA, Courpas GE, Walsh PC, et al. Correlation of postoperative pain to quality of recovery in the immediate postoperative period. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:516–22. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.07.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kehlet H. Surgical stress: The role of pain and analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:189–95. doi: 10.1093/bja/63.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankovic Z, Ahmad N, Ravishankar N, Archer F. Transversus abdominis plane block: How safe is it? Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1758–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181853619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farooq M, Carey M. A case of liver trauma with a blunt regional anesthesia needle while performing transversus abdominis plane block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:274–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erol DD, Yilmaz S, Polat C, Arikan Y. Efficacy of thoracic epidural analgesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Adv Ther. 2008;25:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Dawlatly AA, Turkistani A, Kettner SC, Machata AM, Delvi MB, Thallaj A, et al. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: Description of a new technique and comparison with conventional systemic analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:763–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadam RV, Field JB. Ultrasound-guided continuous transverse abdominis plane block for abdominal surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:333–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.83676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joris J, Thiry E, Paris P, Weerts J, Lamy M. Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Characteristics and effect of intraperitoneal bupivacaine. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:379–84. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199508000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander JI. Pain after laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:369–78. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolchard S, Davies R, Martindale S. Efficacy of the subcostal transversus abdominis plane block in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Comparison with conventional port-site infiltration. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28:339–43. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.98331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R, Bogra J, Kothari N, Kohli M. Postoperative analgesia with intraperitoneal fentanyl and bupivacaine: A randomized control trial. Can J Med. 2010;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucuk C, Kadiogullari N, Canoler O, Savli S. A placebo-controlled comparison of bupivacaine and ropivacaine instillation for preventing postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Today. 2007;37:396–400. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta A, Thörn SE, Axelsson K, Larsson LG, Agren G, Holmström B, et al. Postoperative pain relief using intermittent injections of 0.5% ropivacaine through a catheter after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:450–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200208000-00040. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredrickson MJ, Seal P. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block for neonatal abdominal surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:469–72. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]