Abstract

Globally, vulture species are experiencing major population declines. The southern African Cape vulture (Gyps coprotheres) has undergone severe population collapse which has led to a listing of Endangered by the IUCN. Here, a comprehensive genetic survey of G. coprotheres is conducted using microsatellite markers. Analyses revealed an overall reduction in heterozygosity compared to other vulture species that occur in South Africa (Gypaetus barbatus, Necrosyrtes monachus, and Gyps africanus). Bayesian clustering analysis and principal coordinate analysis identified shallow, subtle population structuring across South Africa. This provides some support for regional natal philopatry in this species. Despite recent reductions in population size, a genetic bottleneck was not detected by the genetic data. The G. coprotheres, however, did show a significant deficiency of overall heterozygosity. This, coupled with the elevated levels of inbreeding and reduced effective population size, suggests that G. coprotheres is genetically depauperate. Given that genetic variation is considered a prerequisite for adaptation and population health, the low genetic diversity within G. coprotheres populations is of concern and has implications for the future management and conservation of this species.

Subject terms: Genetic variation, Behavioural genetics

Introduction

Examining the spatial distribution of genetic diversity, within and among populations, is important in the management and conservation of threatened taxa1,2. Habitat fragmentation and reduced effective population size can affect the genetic structure of endangered species3, by increasing levels of inbreeding and genetic drift within populations which in turn reduces the amount of genetic diversity within the gene pool4,5. Reduced genetic diversity in turn can have detrimental effects on species ability to recover from demographic, environmental and genetic stochasticity6, and can be a contributing factor in reduced long- and short-term survival of endangered species3,7.

Global vulture populations have plummeted in recent years7–10. During the last decade, Africa and Asia have experienced the highest decrease in vulture populations8,9,11,12, as such these species are conservation priorities. There are 23 extant vulture species worldwide, of which 16 species are currently classified as threatened to critically endangered10. As a result, the majority of species are now endangered or critically endangered10. African vultures are particularly vulnerable, with a recent study suggesting that populations of six of the eleven African species have declined by an average of 62% over the past 30 years9. Despite this alarming trend, little is known about the population genetics of African vultures and what impact the reduction in population size has had on the genetic diversity of these birds. Conducting thorough genetic assessments of wide-ranging, highly mobile species, such as vultures, which move between countries or even between continents, poses a considerable challenge. For vultures, and many other raptors, direct estimates of abundance, natal philopatry and dispersal are particularly challenging because individuals are not only difficult to capture and mark, but re-capture rates are also very low13–15. Genetic methods can be valuable tools to evaluate genetic diversity, effective population size and gene flow among fragmented populations and have shown to be useful in highly mobile species15–17.

Although the Cape vulture (Gyps coprotheres) is one of the most well studied vulture species in southern Africa, after decades of conservation efforts the population continues to decline9,12,18,19. The species is currently listed as Endangered on the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red data list19. The decline of this species is largely attributed to anthropogenic factors including habitat loss, reduced food supply and poisoning20. Current estimates suggest a wild population of approximately 9400 individuals21.

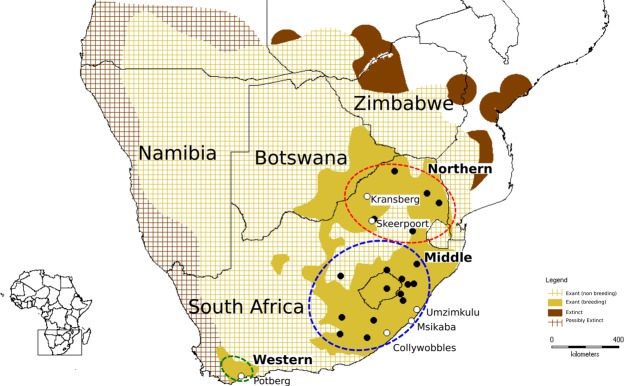

The distribution of the species has also undergone a significant reduction with birds no longer breeding in much of their historical range (Fig. 1). This species flies extensive distances to forage, and has been sighted in Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland, but breeding colonies are almost exclusively restricted to South Africa19,22. The home ranges for juvenile birds are much larger than that of breeding adults covering a foraging range up to 482 276 km2 13. Younger birds are inefficient feeders and forage more widely to avoid feeding competition with adults22–25. Literature indicates that individuals return to their natal colony to settle and breed26, but natal philopatry has only been confirmed in a few ringing studies27,28. There are currently three core G. coprotheres breeding populations in South Africa: one in northern South Africa (Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces); the second in the high lying regions of the KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa and Lesotho14,18,29; and an small isolated breeding colony in the Western Cape province of South Africa18. The connectivity of these regional populations is unknown. Strong natal philopatry should result in pronounced populations substructure even in species such as vultures that travel extensive distances.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Gyps coprotheres. Extant and extinct geographical distribution of Gyps coprotheres is shown. The 24 sampling localities for the 605 Gyps coprotheres included in the present study are shown (black dots). White dots indicate the six breeding colonies. Northern, Middle and Western regional grouping are also shown.

This study aims to determine how the recent dramatic reduction in population size has shaped the genetic diversity of G. coprotheres. The genetic diversity of South African G. coprotheres populations was evaluated using microsatellite loci. The genetic diversity was compared to three ecologically similar vulture species also found in South Africa, but which have wider continental-scale distributions, namely the near-threatened bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus); the critically endangered hooded vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus); and the critically endangered white-backed vulture (Gyps africanus)10. In addition, this study aims to examine the regional connectivity among six breeding colonies and provide insight into natal philopatry in G. coprotheres.

Results

Thirteen microsatellite loci were amplified in 605 G. coprotheres individuals collected from across the southern African distribution of the species. The missing data included in the final data set varied across loci, but was minimal (mean = 11%). Identity analysis estimates showed that all specimens were unique (i.e. no identical specimens) and all 605 G. coprotheres individuals were used in subsequent analyses. The mean null allele (No) frequency across the 13 microsatellite loci for G. coprotheres data was 5.4% (Supplementary Table 1). The paired t-tests did not indicate significant difference (p-value > 0.05) between uncorrected and correct FST values, suggesting that null alleles have a very limited effect on the genetic structuring analyses in South African G. coprotheres. Therefore all 13 microsatellite loci were used in subsequent analyses.

Genetic diversity

Genetic diversity estimates indicated that all 13 loci were polymorphic (Table 1). No signs of linkage disequilibrium were detected in the data. Six loci (BV11, BV12, BV13, Gf3H3, Gf9C and Gf11A4) were identified as moderately to highly informative (PIC > 0.5). The number of alleles per locus ranged from 6 (BV2) to 21 (Gf9C). All loci deviated significantly from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium except for Gf11A4 (HWD >0.004, Table 1). One locus showed elevated levels of heterozygosity (BV11, F = −0.38). Seven loci (BV5, BV6, BV9, BV13, BV14, BV20 and Gf8G) showed signs of heterozygote deficiency (F > 0.15). The overall genetic diversity varied among the 24 sampling localities across South Africa (Supplementary Table 1). The mean number of alleles ranged from 0.54 (Mala Mala) to 7.39 (Highmoor). The observed heterozygosity ranged from 0.08 (Mala Mala) to 0.47 (Smithfield). The inbreeding coefficient ranged from −1.00 (Mala Mala) to 0.29 (Thomas River).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of the 605 Gyps coprotheres genotyped in the present study.

| Locus | A | No | FSTA | FSTB | Ho | uHe | HWD | F | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV2 | 6 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| BV5 | 8 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.05 |

| BV6 | 13 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.11 |

| BV9 | 9 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

| BV11 | 15 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.00 | −0.38 | 0.54 |

| BV12 | 20 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.82 |

| BV13 | 10 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| BV14 | 11 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.15 |

| BV20 | 7 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| Gf3H3 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.55 |

| Gf8G | 15 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.32 |

| Gf9C | 21 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.84 |

| Gf11A4 | 10 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.70 |

| Mean | 12 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.17 | — |

Number of alleles (A), null allele frequency (No), uncorrected and corrected fixation indices (FST), observed heterozygosity (Ho), unbiased expected heterozygosity (uHe), deviation from Hardy-Weinberg (HWD) p-value, inbreeding coefficient (F) and polymorphic information content (PIC). Null allele frequency was estimated using the EM algorithm. The FSTA uncorrected and FSTB null allele corrected.

Based on collection locality samples were grouped into three geographic regions (Western, Middle and Northern regions see Fig. 1). Genetic diversity estimates varied among the three geographic regions (Table 2). The number of alleles were the lowest in the Western region (45 alleles) and highest in the Middle region (134 alleles). Although the mean number of alleles differed among the three geographic regions, with the Middle region having the highest mean number of alleles (Ā = 10.308; SE = 1.082), when allelic richness was estimated using the rarefaction index (accounting for the differences in sample sizes among the regions) little difference in allelic richness was observed. The number of private alleles ranged from 0.41 alleles (Western) to 0.79 alleles (Northern). Similar levels of observed heterozygosity were observed across the three regions (observed heterozygosity <0.39). No signs of excess heterozygosity were observed in any of the three regions. The Middle region and the Northern region showed signs of heterozygote deficiency (F > 0.15).

Table 2.

Genetic diversity estimates for the 605 Gyps coprotheres grouped by geographic region and for the 266 Gyps coprotheres individuals grouped by breeding colony.

| N | A | Ā | AR | AP | Ho | uHe | F | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region N = 605 | Western | 18 | 45 | 3.46 (0.75) | 3.36 | 0.41 | 0.33 (0.10) | 0.34 (0.09) | 0.06 (0.08) |

| Middle | 462 | 134 | 10.31 (1.08) | 3.96 | 0.74 | 0.38 (0.10) | 0.40 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.07) | |

| Northern | 125 | 95 | 7.31 (1.09) | 4.14 | 0.79 | 0.38 (0.09) | 0.43 (0.08) | 0.19 (0.09) | |

| Mean | 91 | 7.03 (0.72) | 3.82 | 0.64 | 0.37 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.14 (0.05) | ||

| Colony N = 266 | Potberg | 18 | 45 | 3.46 (0.75) | 3.36 | 0.4 | 0.33 (0.10) | 0.34 (0.09) | 0.06 (0.08) |

| Collywobbles | 66 | 57 | 4.39 (0.82) | 3.39 | 0.20 | 0.37 (0.10) | 0.35 (0.09) | −0.05 (0.07) | |

| Msikaba | 50 | 58 | 4.46 (0.95) | 3.65 | 0.21 | 0.38 (0.10) | 0.39 (0.09) | 0.06 (0.09) | |

| Umzimkulu | 53 | 54 | 4.15 (0.93) | 3.51 | 0.17 | 0.38 (0.10) | 0.38 (0.09) | −0.01 (0.06) | |

| Skeerpoort | 43 | 52 | 4.00 (0.89) | 3.43 | 0.19 | 0.35 (0.09) | 0.39 (0.09) | 0.06(0.10) | |

| Kransberg | 36 | 50 | 3.85 (0.75) | 3.44 | 0.08 | 0.38 (0.09) | 0.39 (0.08) | 0.06 (0.08) | |

| Mean | 44 | 53 | 4.05(0.34) | 3.46 | 0.21 | 0.37 (0.04) | 0.38 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.03) |

Number of individuals (N), total number of alleles (A), mean number of alleles (Ā), allelic richness (AR), private alleles (AP), observed heterozygosity (Ho), unbiased expected heterozygosity (uHe), and inbreeding coefficient (F). Allelic richness for each region was based on the minimum number of gene copies. Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

In addition to the regional grouping, 266 samples collected from six breeding colonies were analysed separately. Genetic diversity also varied among the six breeding colonies (Table 2). The number of alleles ranged from 45 alleles in Potberg to 58 alleles in Msikaba. Allelic richness estimates showed little difference across the six colonies. Similar levels of heterozygosity were observed in all six colonies (observed heterozygosity <0.39). No signs of excess heterozygosity were observed in any of the six colonies. The inbreeding coefficient ranged from −0.045 in Collywobbles to 0.062 in Potberg.

South African representatives of G. barbatus (n = 54), N. monachus (n = 54), and G. africanus (n = 68) were also included and genotyped using the same microsatellite loci, to allow for direct comparison of genetic diversity values. The mean observed heterozygosity in G. coprotheres (Ho = 0.38) was much lower than that observed in G. barbatus (Ho = 0.50), N. monachus (Ho = 0.71), and G. africanus (Ho = 0.65). Gyps coprotheres and the much smaller, isolated South African G. barbatus population showed elevated levels of inbreeding (mean F = 0.17). Inbreeding was not detected in the other two vulture species N. monachus F = −0.07 and G. africanus F = 0.07 (Supplementary Table 2).

Population structure

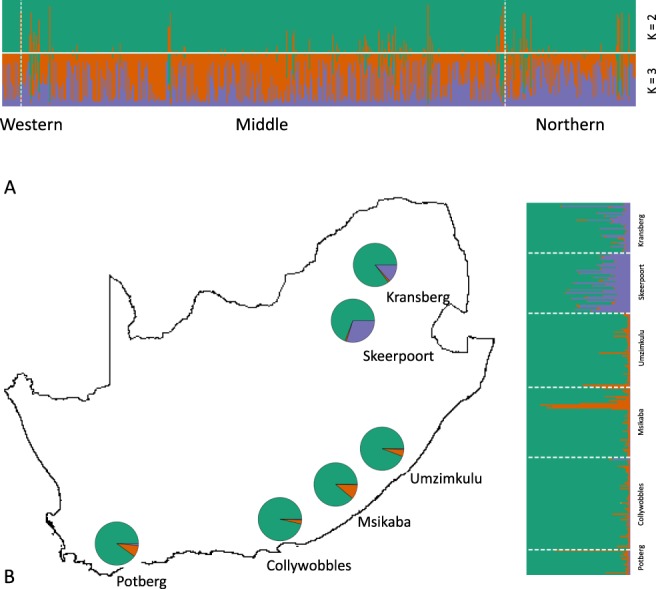

Two optimal genetic clusters were recovered from the Bayesian clustering analysis conducted on the 605 G. coprotheses, including all 24 sampling localities (K = 2, delta K = 42.16; Supplementary Table 3). Figure 2 shows the structure barplots for all 605 G. coprotheses samples grouped by geographic region for K = 2 and K = 3. No distinct geographic structure was observed in the data across both K-values. However, significant genetic differentiation was observed in all region pairs shown in the pairwise FST values reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 2.

STRUCTURE bar plots the 605 Gyps coprotheres grouped by geographic region (A) and 266 individuals collected at the six breeding colonies (B). Each vertical line in the bar plot represents an individual and is coloured according to individual’s estimated membership coefficient (Q) values. Distribution of mean Bayesian assignment probabilities for each grouping is shown on the maps.

The second Bayesian clustering analysis, conducted using only the 266 G. coprotheses collected at the six breeding colonies, recovered three genetic clusters (K = 3, delta K = 11.05; Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). All three genetic clusters were again present across the six breeding colonies. In this case, the two colonies (Skeerpoort and Kransberg) are distinct from other colonies. Surprisingly, the geographically isolated Potberg colony in Western Cape, South Africa is not distinguishable from colonies in Eastern Cape and Kwazulu-Natal provinces. However, significant pairwise FST values (p-value < 0.003) were recovered between the Potberg colony and all colony pairs and the Skeerpoort colony and all colony pairs as shown by pairwise FST estimates reported in Supplementary Table 5. Pairwise FST analysis showed no clear genetic partitioning when individuals were assigned to localities (Supplementary Table 6). Mantel tests showed no correlation between pairwise geographic distances and pairwise genetic distances (individuals grouped by locality: R = 0.011, p-value = 0.317; individuals grouped by colony: R = 0.052, p-value = 0.105).

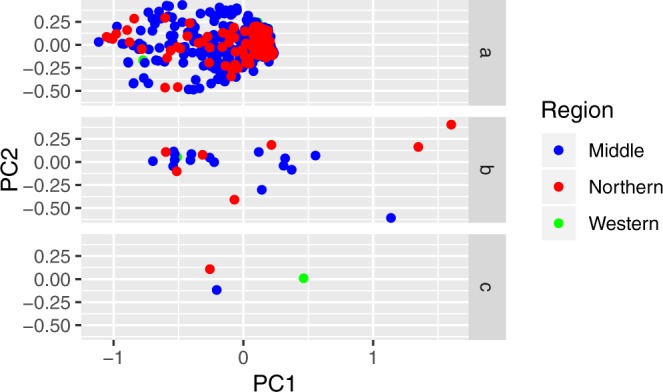

Principle coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed on G. coprotheses individuals and G. coprotheses samples grouped by populations (where population is either locality, region or colony groupings). Figure 3 shows the PCoA for all 605 G. coprotheres sampled. When all 605 G. coprotheres individuals were analysed (Fig. 3 graph a) no correlation between individual genetic distance and locality was observed. Similarly, no correlation was observed when samples were grouped by the 24 sampling localities (Fig. 3 graph b). In contrast, when individuals were grouped by the three geographic regions (Fig. 3 graph c), all three regions were genetically distinguishable.

Figure 3.

Principle coordinate analyses for the 605 Gyps coprotheres. Graph a shows all 605 G. coprotheres samples. Graph b shows analysis for all samples grouped into the 24 sampling localities. Graph c shows analysis of all samples grouped by geographic region. The colours represent the regional groupings where Western is green, Middle is blue and Northern is red.

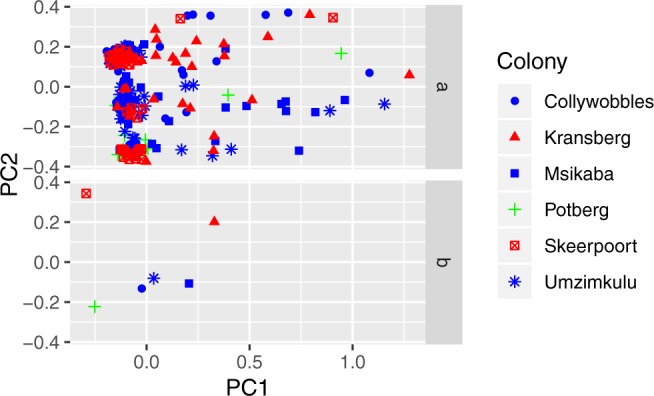

In PCoAs for the 266 G. coprotheres individuals collected at the six breeding colonies (Fig. 4) no correlation between individual genetic distances and colonies were observed (Fig. 4 graph a). The PCoA showing individuals grouped by colony (Fig. 4 graph b), support the STRUCTURE results by grouping together the three colonies from the Eastern Cape and Kwazulu-Natal provinces (Collywobbles, Msikaba and Umzimkulu). Interestingly, the PCoA was able to separate the Skeerpoort and Kransberg colonies.

Figure 4.

Principle coordinate analyses for the 266 Gyps coprotheres collected from six breeding colonies across South Africa. Graph a shows all 266 individuals sampled from the six breeding colonies. Graph b shows samples grouped into the six breeding colonies. The colours represent the regional groupings where Western is green, Middle is blue and Northern is red.

AMOVA results reported that the global FST values for G. coprotheses individuals grouped by sampling locality, G. coprotheses assigned to geographic regions and only G. coprotheses collected at the six breeding colonies deviated significantly from zero (FST > 0.01; p-value = 0.00). The majority of genetic variation, however, occurred within individuals (64–77%; Supplementary Table 7).

Population connectivity

Migration rates below 0.10 were used to indicate demographic independence30. The migration rates (m) for G. coprotheses grouped by geographic region showed that the highest gene flow occurred from the Middle region to the Northern region (m = 0.31; confidence interval (CI) = 0.30 to 0.32; Table 3). This is unsurprising as these birds are highly mobile and travel long distances to forage14 and the majority of these samples were collected from feeding sites. Interestingly, the rates of migration between the Western and Northern regions are low (m < 0.04), indicating that these two regions are demographically independent from each other. The results suggest that the Middle region may act as a source population for both the Western and Northern regions.

Table 3.

Migration rates estimated using BayesAss for the 605 Gyps coprotheres individuals grouped by geographic region.

| Source | Middle | Northern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | ||||

| Recipient | Western | 0.68 (0.67, 0.70) | 0.29 (0.26, 0.31) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) |

| Middle | 0.00 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.98 (0.98, 0.98) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.02) | |

| Northern | 0.00 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.31 (0.30, 0.32) | 0.69 (0.68, 0.69) |

BayesAss estimates the fraction of migrants in each population from different sources (populations). The source populations are given in columns and recipient populations in rows. Bold values along diagonal are non-migrant proportions. The 95% confidence interval is provided in parentheses. Migration rates below 0.10 were used to indicate demographic independence30.

The migration rates between G. coprotheses collected at the six breeding colonies showed that the highest migration rates were observed out of the Collywobbles colony to all other colonies (m > 0.20; Table 4). Potberg, Msikaba, Umzimkulu, Skeerpoort and Kransberg colonies are all demographically independent from each other (m < 0.10).

Table 4.

Migration rates estimated using BayesAss for only the 266 Gyps coprotheres collected at the six breeding colonies.

| Source | Collywobbles | Msikaba | Umzimkulu | Skeerpoort | Kransberg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potberg | |||||||

| Recipient | Potberg | 0.68 (0.67, 0.69) | 0.23 (0.19, 0.27) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) |

| Collywobbles | 0.00 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.15) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | |

| Msikaba | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.24 (0.18, 0.29) | 0.69 (0.67, 0.70) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | |

| Umzimkulu | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01 | 0.27 (0.23, 0.30) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.70 (0.67, 0.74) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | |

| Skeerpoort | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.24 (0.21, 0.26) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.03) | 0.73 (0.71, 0.76) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | |

| Kransberg | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 0.26 (0.24, 0.29) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04) | 0.68 (0.67, 0.68) |

BayesAss estimates the fraction of migrants in each population from different sources (populations). The source populations are given in columns and recipient populations in rows. Bold values along diagonal are non-migrant proportions. The 95% confidence interval is provided in parentheses. Migration rates below 0.10 were used to indicate demographic independence30.

Population bottleneck

Table 5 shows the results for the bottleneck analysis for all 605 G. coprotheses grouped by geographic region. The heterozygote excess method (Hx) for both mutation models showed no signs of recent bottleneck (p-value > 0.003). No significant deviation from the normal L-shaped distribution (Mode-shift) was observed in any of the regions. A similar result was observed when G. coprotheses from the six breeding colonies were analyzed (Table 5). The heterozygote excess method for both models showed no sign of a recent bottleneck (p-value > 0.05); neither did the Mode-shift test. Both the Wilcoxon test for heterozygote excess and the Mode-shift provide strong evidence that G. coprotheres populations, when considering both individuals grouped by region and only those individuals collected at the six breeding colonies, have not undergone a recent bottleneck.

Table 5.

Bottleneck results (p-values) for the 605 Gyps coprotheres grouped by geographic region and for only the 266 Gyps coprotheres collected at the six breeding colonies.

| Wilcoxon test | Wilcoxon test | Sign test | Mode-shift | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One tailed for Hx | One tailed for Hd | SMM | TPM | |||||||

| SMM | TPM | SMM | TPM | Hd: Hx | p-value | Hd: Hx | p-value | |||

| Region N = 605 | Western | 0.984 | 0.984 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 6:4 | 0.218 | 6:4 | 0.221 | No |

| Middle | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 13:0 | 0.000 | 13:0 | 0.000 | No | |

| Northern | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 13:0 | 0.000 | 12:1 | 0.000 | No | |

| All regions | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 13:0 | 0.000 | 12:1 | 0.000 | No | |

| Colony N = 266 | Potberg | 0.984 | 0.984 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 6:4 | 0.210 | 6:4 | 0.213 | No |

| Collywobbles | 0.995 | 0.958 | 0.006 | 0.051 | 9:2 | 0.011 | 8:3 | 0.049 | No | |

| Msikaba | 0.991 | 0.920 | 0.012 | 0.097 | 7:3 | 0.066 | 7:3 | 0.075 | No | |

| Umzimkulu | 0.958 | 0.861 | 0.051 | 0.160 | 7:4 | 0.187 | 6:5 | 0.410 | No | |

| Skeerpoort | 0.884 | 0.813 | 0.138 | 0.216 | 7:3 | 0.081 | 6:4 | 0.230 | No | |

| Kransberg | 0.997 | 0.958 | 0.005 | 0.051 | 9:2 | 0.011 | 8:3 | 0.051 | No | |

| All colonies | 0.999 | 0.993 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 11:1 | 0.001 | 8:4 | 0.089 | No | |

Two mutation models were used the stepwise mutation model (SMM) and the two-phase mutation model (TPM; using 90% SMM). Wilcoxon signed ranked tests for heterozygous excess (one tailed Hx) and heterozygous deficiency (one tailed Hd), a sign test and the Mode-shift test for bottleneck detection. Significant p-values are in bold and have been adjusted using the Bonferroni correction (p-value = 0.003).

Interestingly, two regions (Middle and Northern) showed significant heterozygosity deficiency (p-value < 0.003) for the Wilcoxon test under both mutation models. Additionally, the sign tests for the Middle region and Northern region indicated significant heterozygosity deficiency (p-value < 0.003) under both mutation models. Both regions significantly deviate from the expected ratio (1:1 for heterozygous deficiency to heterozygous excess) for non-bottlenecked, mutation equilibrium populations. When G. coprotheres was analyzed as a single population, a similar result was observed with significant heterozygosity deficiency (p-value < 0.003) for the Wilcoxon test under both mutation models. G. coprotheres population deviated from the expected ratio (1:1 for heterozygous deficiency to heterozygous excess) for non-bottlenecked, mutation equilibrium populations. None of the colonies deviated from the expected ratio for any of the tests. However, when all individuals collected from the six breeding colonies were observed as a single colony unit, significant deviation from the expected Wilcoxon test for heterozygous deficiency and sign test under SMM was observed. The heterozygous deficiency indicates that when the breeding colonies are considered as a single colony unit, they do not behave in mutation-drift equilibrium.

Effective population size (Ne) was estimated assuming both monogamous and random mating for G. coprotheses. The monogamous mating model estimated Ne = 409 individuals (confidence interval (CI): 318.5; 537.2) the ratio of effective population size to census population size (Ne/N)31 was 0.044. When the random mating model was selected Ne = 208 individuals (CI: 161.4; 274.6) Ne/N = 0.022. This is much lower than that reported number of G. coprotheses in recent census data (approximate 9400 individuals)19.

Discussion

G. coprotheres has a relatively narrow distribution in comparison to other African vultures, which have continental scale distributions. As such this species provides a unique opportunity for us to intensively sample across the distribution of the species and thoroughly assess the genetic diversity of the species. This study represents the first comprehensive genetic assessment of the endangered G. coprotheres and provides important genetic baseline data for the conservation and management of the species.

Low levels of observed heterozygosity (mean Ho = 0.38) in G. coprotheres were recorded in this study. Genetic diversity estimates of G. coprotheres were also lower than that observed in the three other ecologically similar vulture species (G. barbatus, N. monachus and G. africanus). Although the sample sizes of the other three species were much smaller than that used for G. coprotheres the same genetic markers were amplified across all vulture species examined, allowing for direct comparison of levels of genetic diversity. This study found higher allelic diversity (number of alleles) in G. coprotheres probably as a result of differences in sample size, but, alarmingly N. monachus and G. africanus showed higher mean observed heterozygosity estimates. N. monachus revealed significantly higher levels of heterozygosity and low levels of inbreeding (F = −0.07). The genetic diversity values for G. africanus and G. barbatus estimated in this study are similar to the values reported in the literature for the Namibian G. africanus population7 and European G. barbatus populations32. This provides support for the results recovered in the present study not being biased by sample size or marker choice, but rather reflect the true levels of genetic variation present in populations of these African vultures. The lower than expected genetic diversity in G. coprotheres is of concern, given that both N. monachus and G. africanus are currently at higher extinction risk than G. coprotheres. N. monachus and G. africanus are currently listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN10. The genetic diversity observed in G. coprotheres was lower than that observed in other threatened raptors such as the Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti)3; and the Eurasian black vulture (Aegypius monachus)33.

The Bayesian assignment tests indicated very shallow genetic structure across the range of the species. However, the pairwise FST values suggested genetic partitioning at a regional scale. Vultures from the two northern colonies (Skeerpoort and Kransberg) were genetically distinct from the other colonies. Given the geographic isolation and small size of the Potberg colony, we expected this colony to be the most effected by genetic drift. Although no marked allele frequency differences were observed in the STRUCTURE analysis, this colony did show the highest private allelic richness which is indicative of restricted gene flow. This is supported by the pairwise FST values in Supplementary Table 5 where Potberg is significantly dissimilar to the other five breeding colonies.

The shallow genetic structuring seen in this species was not unexpected; given that birds often show shallower genetic structuring than that of other vertebrate species34–37. The lack of genetic structuring in avian populations is attributed to high dispersal capabilities38–40. A similar pattern of low genetic structure was observed in Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus)41 and griffon vulture (G. fulvus)42. In contrast, other wide-ranging vulture and raptor species such as the bearded vulture G. barbatus43, the Eurasian black vulture (Aegypius monachus)33; and the white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla)44 have shown high levels of population differentiation.

The degree of natal philopatry (the likelihood that individuals breed at or near their place of origin) can influence the extent of genetic structuring in animal populations. Data from radio tracking and ringing studies have suggested that G. coprotheres exhibit natal philopatry27,28. Analysis of individuals collected from the six breeding colonies across South Africa did not support strong natal philopatry in this species, rather the genetic data suggests regional philopatry. The migration and pairwise FST results showed that the Potberg colony was demographically independent from all other colony pairs. The Skeerpoort and Kransberg colonies were also distinct, while the Collywobbles, Msikaba and Umzimkulu colonies seems to be operating as a single large regional unit.

G. coprotheres are listed as endangered by IUCN due to declines in overall population numbers19. Some recent surveys have however, reported increasing population number in some areas45. Populations that have experienced a recent bottleneck event are usually characterized by an excess of heterozygotes, as opposed to a population at mutation-drift equilibrium46,47. Over time however, inbreeding and genetic drift following a severe bottleneck event would lead to populations containing more homozygotes (heterozygote deficient). In the data generated in the present study, no signs of heterozygosity excess were observed in South African G. coprotheres populations. This could be because G. coprotheres may be currently experiencing a bottleneck and not enough generations have passed for the genetic signal of this event to be detected. In contrast, population genetic theory also suggests that G. coprotheres populations may have reduced genetic variation due to older bottleneck events2,48. This latter hypothesis was supported by results of Wilcoxon signed rank tests which found significant heterozygote deficiency in vultures from all three geographic regions and four colonies (Potberg, Collywobbles, Msikaba and Kransberg).

Identifying and prioritizing G. coprotheres populations, which have higher genetic variability, is an important step forward in conserving these birds. Genetically diverse populations could be valuable source populations for future translocation programmes. Six of the 24 localities showed elevated heterozygosity (F < 0; (Commando Drift and Elliot in Eastern Cape; Natal Midlands in KwaZulu-Natal; Soetdoring in Freestate; Blouberg in Limpopo; and Mala Mala in Mpumalanga), whereas all other localities showed reduced heterozygosity. The isolated Potberg colony in the Western Cape had the lowest genetic variation of all the breeding colonies. This is not unexpected given the isolated nature of this colony. Careful management and monitoring of this colony is needed to avoid the detrimental effects of inbreeding and genetic drift. Given the shallow genetic structuring observed across the range of the species and the high levels of gene flow among breeding colonies, the present study suggests that the entire South African G. coprotheres population be managed as a single management unit.

The results from this study showed low levels of genetic diversity and variability in South African G. coprotheres populations. This, together with the rapid decline of this species9,21, highlights the need for conservation strategies to include the maintenance of genetic diversity as a population management tool. Reductions in genetic diversity can have serious implications on the evolutionary potential of a species49. The present study highlights the utility of microsatellite markers for the assessment and monitoring of genetic diversity in an African vulture species. The data produced in this study can be used as a baseline for future genetic monitoring and species recovery programmes.

Material and Methods

Sampling

A total of 605 G. coprotheres from 24 localities, across the South African distribution of the species, were sampled for this study (Supplementary Table 8). Based on sample localities, samples were grouped into three geographic regions: Western (n = 18), Middle (n = 462) and Northern (n = 125). In addition to the regional grouping, the 266 samples collected from six breeding colonies (Fig. 1) were analysed separately. South African representatives of G. barbatus (n = 54), N. monachus (n = 54), and G. africanus (n = 68) were also included and genotyped using the same microsatellite loci, to allow for direct comparison of genetic diversity values.

Samples consisted of feather samples, collected opportunistically from feeding sites, sites of electrocutions, poisoning events and below nests at six main breeding colonies18. Blood samples were also collected when vultures were captured and fitted with global positioning system/global system for mobile transmitters14. Bloods were stored on Whatman FTA® Elute cards (Sanford, USA). Archival museum samples (dried skin snips) were sourced from local South African museums (Supplementary Table 8). Ethical approval was obtained for this study from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Animal Ethics subcommittee (Reference number: 045/15/Animal) and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

DNA extraction

The NucleoSpin® Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) was used for all DNA extractions. Extractions protocols were modified slightly for feather and archival samples to improve DNA yield. Modifications included: incubation of the sample and proteinase K for 48 hours in a shaking water bath (56 °C), the lysate was incubated in B3 buffer for 45 minutes (70 °C), the final volume of pre-warmed Buffer BE was decreased to 80 μl and the samples were incubated at 70 °C for 20 minutes followed by centrifuging and then reapplication of the solution onto the membrane and a final incubation at 70 °C for an additional five minutes followed by a final centrifuging step.

Microsatellite amplification

Thirteen microsatellite loci were chosen from a suite of markers used in previous studies of G. fulvus50 and G. barbatus51 (Supplementary Table 9). The 13 loci were amplified in six multiplex reactions (Supplementary Table 9) using the KAPA2GTM Fast Multiplex PCR kit (KAPA Biosystems). The 10 μl reactions consisted of ~2–30 ng template DNA, 5 μl KAPA2G Fast Multiplex mix, 0.2 μM of each primer, 0.1 μl of 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) and purified water. In reactions performed using DNA extracted from feather and archival samples, template DNA was increased to ~20–200 ng to improve amplification success. The cycling parameters for all loci followed the standard KAPA2GTM Fast Multiplex PCR kit protocol except for multiplex 1, where the annealing temperature was reduced to 58 °C. All amplified products were sent to the Central Analytical Facility at Stellenbosch University, South Africa for fragment analysis. The software GeneMarker v2.4.0 (Soft Genetics) was used for genotype scoring. To ensure genotyping consistency, all archival samples were re-amplified, and each locus was genotyped multiple times (up to five times). In addition, 20% of all feather, muscle and blood samples were re-amplified multiple times (up to five times) to verify the reliability of the data.

Data analysis

Assessing genetic variation

To ensure that duplicated genotypes were not included when feathers were collected, identity analysis was performed in Cervus v3.0.752. Cervus was also used to estimate polymorphic information content (PIC) for each locus. Null allele frequencies for each locus were estimated in FreeNA53 using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm54. Because null alleles can bias population structure analysis55, uncorrected global FST were compared to FST values corrected using the excluding null alleles (ENA) method53 using a paired t-test. Linkage disequilibrium was tested using Genepop v4.256. Deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were estimated in GenAlEx v6.50257. The effective population size (Ne) was estimated in NeEstimator v2.0158 implementing both random and monogamous mating.

Genetic diversity estimates (number of alleles, observed heterozygosity, unbiased expected heterozygosity and inbreeding coefficient) were calculated in GenAlEx. Tests for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were performed in Genepop. Allelic richness was estimated in FSTAT v2.9.3.259. The observed number of alleles in a population is dependent on sample size and given the opportunistic nature of sampling used in this study sample size varied across localities. Consequently, allelic richness was calculated using a rarefaction index estimated in FSTAT and the number of private alleles within populations were estimated using the rarefaction method implemented in HP-RARE v1.0 software60. All multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction.

Population structure

Bayesian assignment tests were performed in STRUCTURE v2.3.4.61. For each analysis ten independent runs were performed consisting of 100000 Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) replicates with a burn-in of 10000 and the proposed number of genetic clusters (K) ranging from one to ten. The admixture ancestry model with correlated allele frequencies was selected for all runs. Sampling locality information was incorporated using the LOCPRIOR model. STRUCTURE Harvester62 was used to estimate the most probable number of genetic clusters63. Membership probabilities (Q-values) for each individual and for each genetic cluster were estimated using ClumpAK64. Bar plots from STRUCTURE runs were created in Pophelper65.

The correct identification of the number of genetic clusters can be challenging if there is unbalanced sampling or complex phylogeographic structure i.e. when there are unequal genetic distances among subpopulations or unbalanced sample sizes66. For this reason, Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was also performed in GenAlEx using pairwise codominant genotypic genetic distance. PCoA does not rely on a model but rather multidimensional scaling to visualize similarity in a dataset.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was performed in GenAlEx. Three AMOVA’s were conducted, one grouping individuals by sampling locality, a second grouping individuals by geographic region. A third AMOVA was conducted only on individuals collected from the six breeding colonies. Pairwise FST values were estimated in FSTAT. Mantel tests67 were performed in GenAlEx, to test for correlation between geographic distance and genetic distance.

Population connectivity

Migration rates (gene flow) between the three geographic regions and the six breeding colonies were estimated in BayesAss v1.368. Two analyses were performed consisting of 10000000 iterations, with a burn-in of 1000000 iterations and a sampling frequency of 90000 iterations. Multiple runs were performed with varying run lengths to ensure MCMC chain convergence. The delta values for each parameter were adjusted to achieve a 20–60% acceptance rate68. In analysis to estimate gene flow among the three geographic regions, the final delta values were delta allele frequency = 0.30, delta migration rate = 0.10 and delta inbreeding coefficient = 0.50. In analysis to estimate gene flow among the six breeding colonies, the final delta values were delta allele frequency = 0.50, delta migration rate = 0.10 and delta inbreeding coefficient = 0.70. For both analyses, migration rates below 0.10 were used to indicate demographic independent populations30.

Population bottleneck

BOTTLENECK v1.2.0269 was used to test for evidence of heterozygosity excess (Hx)5,47 in G. coprotheres populations. Two analyses were performed, one grouping individuals by geographic region, and a second only including individuals collected at the six breeding colonies. Each analysis ran two mutation models. The conservative stepwise mutation model (SMM) and the two-phase model (TPM) with 90% stepwise mutation70,71 and a variance of 1269 to include the observed range of multistep mutations in natural populations72. Two statistical tests (Wilcoxon sign-rank test and the sign test) as well as a qualitative test (Mode-shift test), were performed. The Wilcoxon sign-rank test is effective in detecting recent declines in effective population size (Ne) and assumes that populations that have recently undergone a decline in effective population size will have a higher level of heterozygosity compared to a population at mutation-drift equilibrium5. The sign test was used to identify the number of microsatellite loci that have either heterozygosity excess (Hx) or heterozygosity deficiency (Hd). Changes in heterozygosity (excess or deficit) can occur after a recent change in the effective population size or if heterozygotes have a selective advantage or disadvantage69. In populations experiencing a bottleneck event, alleles are usually lost faster than heterozygosity, thus producing a heterozygote excess47. The Mode-shift is a qualitative indicator that can differentiate between bottlenecked and stable (non-bottlenecked) populations. This test can detect the genetic changes caused by a population decline within a few dozen generations73. Therefore, only recent bottleneck events will be identified using this method.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Rated Researcher grant awarded to S. Willows-Munro by the National Research Foundation (NRF, South Africa). The first author received a free-standing MSc bursary from the NRF. The authors thank the curators of the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History (Pretoria, South Africa), Durban Natural Sciences Museum (Durban, South Africa), Iziko Museums (Cape Town, South Africa), National Museum (Bloemfontein, South Africa) and National Zoological Gardens of South Africa (Pretoria, South Africa) for providing access to archival samples. Many thanks to L. Arnot, A. Botha, M. Burke, A. Butt, B. Coversdale, C. Downs, B. Hoffman, S. Krüger, S. McPherson, W. Neser, M. Pfeiffer, K. Shaw, L. Thompson and R. Visagie, who collected samples in the field. Ethical approval was obtained for this study from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Animal Ethics subcommittee (Reference number: 045/15/Animal). All necessary sampling permits were obtained through Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife (Permit number: OP3407/2016) and the National Department of Environmental Affairs (Permit Numbers: 05054, 27273 and 28553).

Author Contributions

C.K. and S.W.-M. designed the experiment, C.K. performed the experiment and did the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, S.W.-M. contributed substantially to the revisions.

Data Availability

The data analysed in this study will be made available as Supplementary information upon publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-41755-4.

References

- 1.Avise JC. A role for molecular genetics in the recognition and conservation of endangered species. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1989;4:279–281. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(89)90203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacy RC. Loss of genetic diversity from managed populations: interacting effects of drift, mutation, immigration, selection, and population subdivision. Conservation Biology. 1987;1:143–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1987.tb00023.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Cruz B, Godoy JA, Negro JJ. Population genetics after fragmentation: the case of the endangered Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti) Molecular Ecology. 2004;13:2243–2255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frankham R. Relationship of genetic variation to population size in wildlife. Conservation Biology. 1996;10:1500–1508. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10061500.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornuet JM, Luikart G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics. 1996;144:2001–2014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lande R. Anthropogenic, ecological and genetic factors in extinction and conservation. Researches on Population Ecology. 1998;40:259–269. doi: 10.1007/BF02763457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arshad M, et al. Genetic variation of four Gyps species (Gyps bengalensis, G. africanus, G. indicus and G. fulvus) based on microsatellite analysis. Journal of Raptor Research. 2009;43:227–236. doi: 10.3356/JRR-08-91.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogada DL, Keesing F, Virani MZ. Dropping dead: causes and consequences of vulture population declines worldwide. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1249:57–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogada Darcy, Shaw Phil, Beyers Rene L., Buij Ralph, Murn Campbell, Thiollay Jean Marc, Beale Colin M., Holdo Ricardo M., Pomeroy Derek, Baker Neil, Krüger Sonja C., Botha Andre, Virani Munir Z., Monadjem Ara, Sinclair Anthony R. E. Another Continental Vulture Crisis: Africa's Vultures Collapsing toward Extinction. Conservation Letters. 2015;9(2):89–97. doi: 10.1111/conl.12182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BirdLife International. IUCN Red List for birds. http://www.birdlife.org (accessed, 15 August 2018).

- 11.Pain DJ, et al. Causes and effects of temporospatial declines of Gyps vultures in Asia. Conservation Biology. 2003;17:661–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01740.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeiffer MB, Venter JA, Downs CT. Identifying anthropogenic threats to Cape Vultures Gyps coprotheres using community perceptions in communal farmland, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Bird Conservation International. 2015;25:353–365. doi: 10.1017/S0959270914000148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamford AJ, Diekmann M, Monadjem A, Mendelsohn J. Ranging behaviour of Cape Vultures Gyps coprotheres from an endangered population in Namibia. Bird Conservation International. 2007;17:331–339. doi: 10.1017/S0959270907000846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeiffer MB, Venter JA, Downs CT. Foraging range and habitat use by Cape Vulture Gyps coprotheres from the Msikaba colony, Eastern Cape province, South Africa. Koedoe. 2015;57:1–11. doi: 10.4102/koedoe.v57i1.1240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Runge CA, Martin TG, Possingham HP, Willis SG, Fuller RA. Conserving mobile species. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2014;12:395–402. doi: 10.1890/130237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JF, Ruegg KC, Smith TB. Combining isotopic and genetic markers to identify breeding origins of migrant birds. Ecological Applications. 2005;15:1487–1494. doi: 10.1890/04-1704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bounas A, et al. Using genetic markers to unravel the origin of birds converging towards pre-migratory sites. Scientific reports. 2018;8:8326. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26669-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolter K, Neser W, Hirschauer MT, Camiña A. Cape Vulture Gyps coprotheres breeding status in southern Africa: monitoring results from 2010–2014. Ostrich. 2016;87:119–123. doi: 10.2989/00306525.2016.1179689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BirdLife International. Species factsheet: Gyps coprotheres. http://www.birdlife.org (accessed, 20 September 2018).

- 20.Boshoff A, Anderson MD. Towards a conservation plan for the Cape Griffon Gyps coprotheres: identifying priorities for research and conservation. Vulture News. 2007;57:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allan, D. The 2015 Eskom Red Data Book of Birds of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland (eds Taylor, M. R., Peacock, F. & Wanless R. M.) 174–178 (BirdLife South Africa, 2015).

- 22.Piper, S. E. Mathematical demography of the Cape Vulture PhD thesis, University of Cape Town (1994).

- 23.Mundy, P. J., Butchart, D., Ledger, J. A. & Piper, S. E. The vultures of Africa. (Academic Press, 1992).

- 24.Duriez O, Herman S, Sarrazin F. Intra-specific competition in foraging Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus: 2. The influence of supplementary feeding management. Bird Study. 2012;59:193–206. doi: 10.1080/00063657.2012.658640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson CT, Miller CK. Recommendations for protecting raptors from human disturbance: a review. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 1997;25:634–638. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piper SE, Mundy PJ, Ledger JA. Estimates of survival in the Cape Vulture, Gyps coprotheres. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1981;50:815–825. doi: 10.2307/4139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson A. Known age Cape Vultures breeding in the wild. Ostrich. 1983;54:179. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirschauer MT, Wolter K, Neser W. Natal philopatry in young Cape Vultures Gyps coprotheres. Ostrich. 2017;88:79–82. doi: 10.2989/00306525.2017.1245683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piper, S. E. et al. Cape Griffon Gyps coprotheres. The Vultures of Southern Africa–Quo Vadis? Proceedings of a workshop on vulture research and conservation in southern Africa (2004).

- 30.Hastings A. Complex interactions between dispersal and dynamics: lessons from coupled logistic equations. Ecology. 1993;74:1362–1372. doi: 10.2307/1940066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frankham R. Efective population size/adult population size ratios in wildlife: a review. Genetics Research. 1995;66:95–107. doi: 10.1017/S0016672300034455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gautschi B, Müller JP, Schmid B, Shykoff JA. Effective number of breeders and maintenance of genetic diversity in the captive bearded vulture population. Heredity. 2003;91:9–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulakakis N, et al. Population structure, diversity, and phylogeography in the near‐threatened Eurasian black vultures Aegypius monachus (Falconiformes; Accipitridae) in Europe: insights from microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA variation. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2008;95:859–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01099.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrowclough, G. F., Johnson, N. K. & Zink, R. M. In Current Ornithology Vol. 2 (ed. Richard F. Johnston) 135–154 (Springer US, 1985).

- 35.Zink, R. M. & Remsen, J. V. In Current Ornithology Vol. 4 (ed Richard F. Johnston) 1–69 (Plenum, 1986).

- 36.Zink, R. M. In Avian molecular evolution and systematics (ed David P Mindell) 301–324 (Academic Press, 1997).

- 37.Evans, P. G. H. In Avian genetics: A population and ecological approach (eds F Cooke & P.A Buckley) 105–162 (Academic Press, 1987).

- 38.Payne Robert B. NATAL DISPERSAL AND POPULATION STRUCTURE IN A MIGRATORY SONGBIRD, THE INDIGO BUNTING. Evolution. 1991;45(1):49–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb05265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stenzel Lynne E., Warriner Jane C., Warriner John S., Wilson Katherine S., Bidstrup Frances C., Page Gary W. Long-Distance Breeding Dispersal of Snowy Plovers in Western North America. The Journal of Animal Ecology. 1994;63(4):887. doi: 10.2307/5266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weatherhead PJ, Forbes MRL. Natal philopatry in passerine birds: genetic or ecological influences? Behavioral Ecology. 1994;5:426–433. doi: 10.1093/beheco/5.4.426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kretzmann MB, et al. Genetically distinct island populations of the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) Conservation Genetics. 2003;4:697–706. doi: 10.1023/B:COGE.0000006123.67128.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Gouar P, et al. Genetic variation in a network of natural and reintroduced populations of Griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus) in Europe. Conservation Genetics. 2008;9:349–359. doi: 10.1007/s10592-007-9347-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Godoy JA, Negro JJ, Hiraldo F, Donázar JA. Phylogeography, genetic structure and diversity in the endangered bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus, L.) as revealed by mitochondrial DNA. Molecular Ecology. 2004;13:371–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hailer F, et al. Phylogeography of the white‐tailed eagle, a generalist with large dispersal capacity. Journal of Biogeography. 2007;34:1193–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01697.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benson PC. A survey of Cape Vulture breeding colonies in South Africa’s northern provinces (Transvaal region)–an update 2013. Ornithological Observations. 2015;6:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hedrick PW, Brussard PF, Allendorf FW, Beardmore JA, Orzack S. Protein variation, fitness, and captive propagation. Zoo Biology. 1986;5:91–99. doi: 10.1002/zoo.1430050204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luikart G, Cornuet JM. Empirical evaluation of a test for identifying recently bottlenecked populations from allele frequency data. Conservation Biology. 1998;12:228–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.96388.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frankham R, Bradshaw CJ, Brook BW. Genetics in conservation management: revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, Red List criteria and population viability analyses. Biological Conservation. 2014;170:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.12.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frankham R. Genetics and extinction. Biological conservation. 2005;126:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2005.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mira S, Billot C, Guillemaud T, Palma L, Cancela ML. Isolation and characterization of polymorphic microsatellite markers in Eurasian vulture Gyps fulvus. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2002;2:557–558. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00314.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gautschi B, Tenzer I, Müller JP, Schmid B. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) and cross-amplification in three Old World vulture species. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:2193–2195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2000.105321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC. Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:1099–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chapuis MP, Estoup A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24:621–631. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horváth MB, Martínez-Cruz B, Negro JJ, Kalmár L, Godoy JA. An overlooked DNA source for non-invasive genetic analysis in birds. Journal of Avian Biology. 2005;36:84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.0908-8857.2005.03370.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raymond M, Rousset F. GENEPOP Version 1.2: Population genetics software for exat tests and ecumenicism. Journal of Heredity. 1995;86:248–249. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research- an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2537–2539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Do C, et al. NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Molecular ecology resources. 2014;14:209–214. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goudet J. FSTAT version 1.2: a computer program to calculate Fstatistics. Journal of Heredity. 1995;86:485–486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalinowski ST. Counting alleles with rarefaction: private alleles and hierarchical sampling designs. Conservation Genetics. 2004;5:539–543. doi: 10.1023/B:COGE.0000041021.91777.1a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Earl DA. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservation Genetics Resources. 2012;4:359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kopelman NM, Mayzel J, Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA, Mayrose I. Clumpak: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2015;15:1179–1191. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Francis R. M. pophelper: an R package and web app to analyse and visualize population structure. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2016;17(1):27–32. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalinowski ST. The computer program STRUCTURE does not reliably identify the main genetic clusters within species: simulations and implications for human population structure. Heredity. 2011;106:625–632. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Research. 1967;27:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson GA, Rannala B. Bayesian inference of recent migration rates using multilocus genotypes. Genetics. 2003;163:1177–1191. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.3.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Piry S, Luikart G, Cornuet JM. BOTTLENECK: a program for detecting recent effective population size reductions from allele data frequencies. Journal of Heredity. 1999;90:502–503. doi: 10.1093/jhered/90.4.502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garza JC, Williamson EG. Detection of reduction in population size using data from microsatellite loci. Molecular Ecology. 2001;10:305–318. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dussex N, Rawlence NJ, Robertson BC. Ancient and contemporary DNA reveal a pre-human decline but no population bottleneck associated with recent human persecution in the Kea (Nestor notabilis) PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0118522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Rienzo A, et al. Mutational processes of simple-sequence repeat loci in human populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:3166–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luikart G, Allendorf FW, Cornuet JM, Sherwin WB. Distortion of allele frequency distributions provides a test for recent population bottlenecks. Journal of Heredity. 1998;89:238–247. doi: 10.1093/jhered/89.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study will be made available as Supplementary information upon publication.