Abstract

Community participation is a central concept for health promotion, covering a breadth of approaches, purposes and activities. This paper reports on a national knowledge translation project in England, UK, which resulted in a conceptual framework and typology of community-based approaches, published as national guidance. A key objective was to develop a conceptual framework linked to sources of evidence that could be used to support increased uptake of participatory methods across the health system. It was recognized that legitimacy of community participation was being undermined by a scattered evidence base, absence of a common terminology and low visibility of community practice. A scoping review, combined with stakeholder consultation, was undertaken and 168 review and conceptual publications were identified and a map produced. A ‘family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing’ was then produced as way of organizing the evidence and visually representing the range of intervention types. There are four main groups, with sub-categories: (i) strengthening communities, (ii) volunteer and peer roles, (iii) collaborations and partnerships and (iv) access to community resources. Each group is differentiated using key concepts and theoretical justifications around increasing equity, control and social connectedness. An open access bibliography is available to accompany the framework. The paper discusses the application of the family of community-centred approaches as a flexible planning tool for health promotion practice and its potential to be used as a framework for organizing and synthesizing evidence from a range of participatory methods.

Keywords: community participation, typology, evidence-based practice, empowerment, public health

INTRODUCTION

Building on an international tradition that places community participation and empowerment central to health promotion, recent international statements have reaffirmed the role of civil society in delivering improvements in population health and tackling health inequity (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2012; World Health Organization, 2016). The perennial challenge for health planners and practitioners is to translate aspirational statements into meaningful, effective programmes that involve and empower communities, whether those communities are geographic or linked by shared interests (Laverack, 2006). Community participation is a multi-dimensional and somewhat nebulous concept covering a breadth of approaches, purposes and types of actions that denote an active role for citizens in shaping their health and the conditions that create good health (Bracht and Tsouros, 1990). Attention to process and context is key and therefore standardized approaches implemented at scale are the exception not the rule (Rifkin, 2014). This creates difficulties for those wishing to synthesize evidence of what works or to select practical methods from an extensive range of community-based interventions. Moreover, despite a rich and methodologically varied evidence base, participatory approaches have not received the same degree of recognition as more traditional prevention programmes within the field of public health. This paper presents a flexible framework for understanding, mapping and planning participatory approaches for health and wellbeing developed in England, UK. It discusses how this framework addresses legitimation challenges around evidence that form barriers to wider adoption of participatory methods. Challenges are grouped into three themes: epistemological, definitional and socio-political.

The contested nature of evidence for population health (Raphael and Bryant, 2002) is key to understanding the first set of legitimation challenges (epistemology). The continued dominance of professionally-derived knowledge built on epidemiological and experimental studies means that experiential and lay evidence, often core to the evaluation of community participation, is less valued (Springett et al., 2007). In public health research, the balance is more often towards measurement of disease not health, and individual-level risk factors not community-level outcomes (Morgan and Ziglio, 2007). Overall, this creates conflicting expectations of what is required for ‘proof of effect’ and what is useful for health promotion practice, as context, culture and capacity are all deemed critical for understanding community processes and impacts (Trickett et al., 2011). Rifkin (2014) argues that the contextual nature of community participation results in a lack of generalizable evidence, which in turn undermines the wider acceptance of these approaches.

The second challenge (definitional) is how a body of knowledge characterized by complexity (Cornwall, 2008; Preston et al., 2010) can be synthesized and models differentiated. There is a lack of consistent terminology around core concepts with a whole plethora of variant terms found within international literature, such as citizen participation, co-production, public involvement and social action (Sarrami-Foroushani et al., 2014). Terms such as ‘empowerment’ may be used with little precision (Woodall et al., 2012) and ‘community’ is itself a contested term subject to interpretation (Yerbury, 2012). A recent systematic review on community engagement and inequalities (O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013) reported that only 8 of the 361 included papers used terms relating to ‘community’ in their title or abstract. Reflecting a similar definitional issue, a scoping review on lay health workers by two of the authors found 70 plus descriptors in international academic literature and these mostly differed from terms used in UK health programmes (South et al., 2013).

The third legitimation challenge (socio-political) arises because the generation of evidence is shaped by the socio-political context in which participation occurs (Raphael and Bryant, 2002; Slutsky et al., 2017). In the UK, as in other countries, community participation initiatives can be at the mercy of policy and funding cycles. Evidence is often assessed early in programme implementation and all too frequently programmes are replaced by newer initiatives (Judge and Bauld, 2006). Threats to sustainability make it difficult to synthesize evidence across models. Additionally, there is a publication bias in international literature towards reporting professionally–led interventions with formal evaluations (South et al., 2013), while evidence from community-led activity often remains hidden (Preston et al., 2010).

In summary, the net result of these three legitimation challenges is a dispersed evidence base for participatory approaches in health (O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013; Sarrami-Foroushani et al., 2014). Overall the lack of a shared language of participation, combined with the importance of contextual knowledge (Trickett et al., 2011), impedes knowledge exchange about potentially transferable models.

Having briefly described the challenges, this paper now reports on a knowledge translation project, which was jointly funded and steered by two national health agencies -NHS England and Public Health England (PHE). The project rationale was the need for better knowledge translation to underpin wider adoption of participatory approaches. Notwithstanding a long tradition of community development in the UK (Fisher, 2011), the health system in England had been slow to recognize the contribution of participatory methods in comparison with individual-level lifestyle interventions. A key objective was therefore to develop a conceptual framework linked to sources of evidence that could be used to support application in practice. In 2015, ‘A guide to community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing’ (PHE and NHS England, 2015) was published and this introduced a new typology–‘the family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing’–as a means of organizing knowledge and understanding the diversity of intervention types. This paper briefly explains how the family was developed prior to presenting the main features.

METHODS

The ‘family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing’ was developed within a broader conceptual framework that summarizes evidence-based justifications for community participation and the determinants of community health (PHE and NHS England, 2015). An iterative process of identifying concepts and grouping interventions, refined through stakeholder consultation and further mapping of literature, produced an explanatory framework (family tree) that represented the range of approaches. The first stage of this process involved a systematic scoping review of reviews with the aim to map evidence in relation to key concepts, main intervention types, outcomes and any potential frameworks to organize evidence on community participation. Systematic scoping reviews are particularly informative in topic areas that cross traditional disciplinary boundaries (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009) and can be used to clarify key concepts and report on the types of evidence that inform practice in a topic area (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015). They involve a comprehensive and systematic search of published and ‘grey’ literature, with attempts to locate unpublished studies, but here is no attempt to synthesize the evidence beyond a thematic narrative summary or ‘map’ (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005).

Due to the breadth of this topic, the systematic scoping review was limited to secondary research (systematic reviews and other research overviews) as this was considered to be the best approach to identify major intervention types and models. Five electronic databases were searched, from January 2004 to April 2014: MEDLINE, IDOX Information Service; CINAHL, Social Policy and Practice and Academic Search Complete. Search terms included synonyms for community/public; concept/review; approaches/interventions; health/wellbeing; inequalities. The full search strategy can be found in the open access bibliography (Bagnall et al., 2015). In addition, 67 websites were searched for published and unpublished literature. Other sources were experts’ libraries; stakeholder input and reference lists of key publications. Titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers against exclusion and inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved by discussion within the academic team.

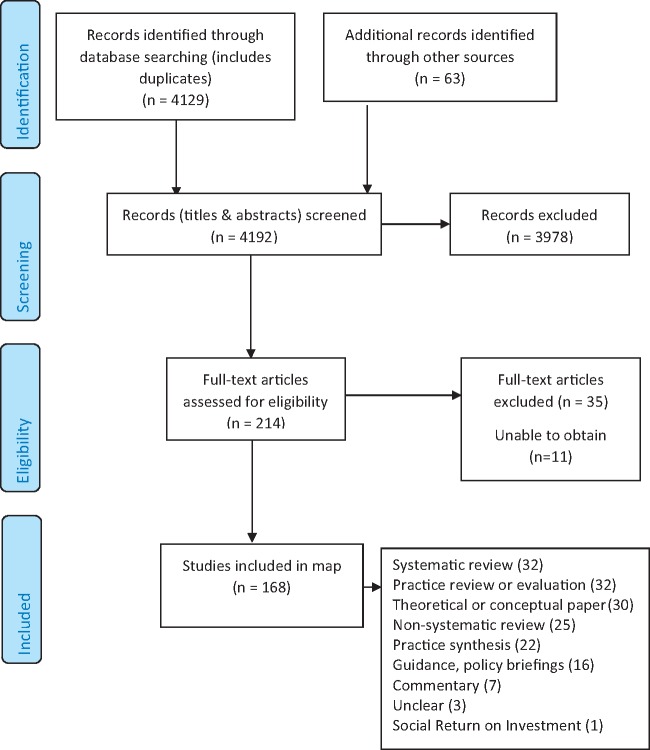

The electronic searches found 4129 titles and abstracts, plus 63 documents obtained from websites and personal libraries of experts (Figure 1). After screening, 168 sources were included to produce a map of relevant secondary and conceptual research (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). Coding using Microsoft Excel then SPSS statistical software was carried out by one reviewer with a random selection checked by a second reviewer. Coding categories included: study type; population; intervention approach; source and whether health and wellbeing outcomes were reported. Relevant review publications encompassed a range of study types (Figure 1). Of these studies, 84 were carried out in and/or were directly relevant to the UK.

Fig. 1:

Study selection flow chart.

The next stage involved designing an initial ‘family tree’ structure to help map interventions. Three groups of approaches were informed by the theories of change articulated by O’Mara-Eves et al. (2013): (i) empowerment, (ii) lay/peer involvement in delivery and (iii) patient/consumer involvement in development. A fourth group was added on connections with community resources. The family was then broadened to reflect the scope of UK and international practice and the importance of interventions that increase social participation (Piskur et al., 2014). The initial family typology was tested for relevance, clarity and fit with practice through discussions with a number of stakeholders working at a national level, two workshops with public health practitioners and a presentation to voluntary sector representatives attending a national strategic network.

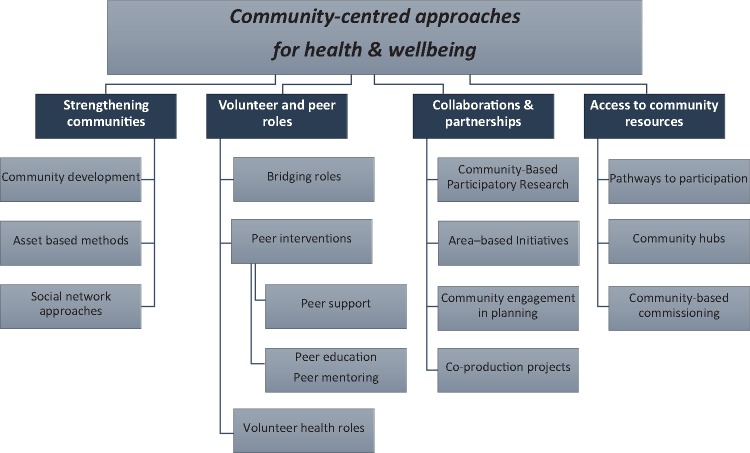

The final stage of development involved mapping the scoping review results back to the emerging typology and expanding sub-categories. Some reviews (n = 21) listed multiple types of interventions (e.g. Coulter, 2010; Elliott, 2012) and these were mapped against the family, leading to additional interventions being included. Theoretical papers were not mapped to the family unless they presented categories of interventions. A final narrative account including definitions was produced to accompany a visual representation of the typology (Figure 2).

Fig. 2:

The family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing (source: PHE and NHS England 2015: 17). This image is made available through the Open Government Licence (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ (last accessed 14 November 2017)) which is a non-exclusive licence.

RESULTS

The family of community-centred approaches is presented within national guidance for working with communities, including communities of identity as well as those linked geographically (PHE and NHS England, 2015). There is an accompanying open access bibliography, listing the 168 publications from the scoping review (Bagnall et al., 2015). The family is situated within a social model of health where community capital is deemed a major determinant (The Marmot Review, 2010) and the lay contribution is valued (Morgan and Ziglio, 2007). Participatory approaches are acknowledged as a mechanism for addressing power imbalances and for changing social conditions, particularly where populations experience marginalization (Wallerstein, 2002). Based on the review of conceptual literature, three central concepts underpin the justifications for, and definitions of, community-centred approaches: empowerment, equity and social connectedness. This distinguishes community-centredness from community-based interventions that merely engage ‘target’ populations as recipients of professionally-led activities. Community-centred approaches:

recognize and seek to mobilize assets within communities, including the skills, knowledge and time of individuals and the resources of community organizations and groups

focus on promoting health and wellbeing in community settings, rather than service settings, using non-clinical methods

promote equity in health and healthcare by working in partnership with individuals and groups that face barriers to good health

seek to increase people’s control over their health and lives

use participatory methods to facilitate the active involvement of community members (PHE and NHS England, 2015: 15).

The ‘family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing’ covers four major groups: (1) strengthening communities, (2) volunteer and peer roles, (3) collaborations and partnerships and (4) access to community resources. A range of interventions, models and methods are mapped to each group, illustrating the heterogeneity of community practice. Sub-groups are identified where approaches share common characteristics; however, it is recognized that there are shared features between groups and sub-groups. Figure 2 shows the visual map of approaches as a family tree and Table 1 provides a summary of the four groups and sub-groups, mapped against examples and outcomes identified through the scoping review. In the guide, a mechanism of change is provided for each group in order to articulate an explanatory account of how these approaches work, including a hypothetical causal pathway between participation, intermediate outcomes and the goals of promoting empowerment, equity and social connectedness. The four groups are therefore distinguished by their focus and means to achieve outcomes, as summarized below:

Table 1:

Community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing–map of intervention types

| Group | Main intervention types | Examples of approaches used in UK | Number of studies–All (UK studies) | Key processes | Example outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengthening communities |

|

|

|

|

|

| Volunteer and peer roles |

|

Community health educators; community navigators; health champions; community food workers; breastfeeding peer support; volunteer-led health walks; befriending schemes. |

|

|

|

| Collaborations and partnerships |

|

|

|

|

|

| Access to community resources |

|

|

|

|

|

Strengthening communities–where approaches involve building on community capacities to take collective action on health and the social determinants of health. There are three sub-groups: community development (Minkler, 2012; Durie and Wyatt, 2013); asset-based approaches (Foot and Hopkins, 2010) and social network approaches (Heaney and Israel, 2008). The key processes are community organizing and capacity building, social action and mutual aid focused on social networks within communities (Laverack, 2006; Minkler, 2012). These approaches tend to be developmental in nature and individual- and community-level outcomes occur as involvement deepens and community members build social action independent of professional services.

Volunteer/peer roles–where approaches focus on enhancing individuals’ capabilities to provide health advice, information and support or organize activities in their or other communities (Lewin et al., 2005). The purpose of roles and peer identity define the sub-groups: bridging roles, such as community navigators; peer-based interventions and volunteer (non-peer) health roles (South et al., 2013). There is a wide range of lay health worker interventions in the public health field, in the UK and internationally (World Health Organization, 2007). In general, these approaches work through utilizing and enhancing the skills, knowledge and commitment of individuals, thereby building community capacity. Whilst the focus is often on the delivery of community-based programmes, a key mechanism is the utilization of natural, or in some instances created, social networks to reach underserved communities (Rhodes et al., 2007).

Collaborations and partnerships–where approaches involve professionals/public bodies working in partnership with communities at any stage across the planning cycle from deciding needs and priorities, to service design, delivery or evaluation. This is a broad strand ranging from consultation methods where there might be minimal shifts in power, through to interventions that place priority setting and resource allocation into the hands of communities. The four sub groups are: Community-Based Participatory Research (Minkler, 2010); area-based initiatives where community participation is integral to action on the wider determinants in a neighbourhood or city (Burton et al., 2004); co-production approaches based on equal and reciprocal relationships between professionals and service users (Realising the Value, 2016) and community engagement in planning (Coulter, 2010) and priority setting (SQW Consulting, 2011). Collaborative approaches require community leadership and capacity building combined with organizational and professional development (Harden et al., 2015), with the goal of creating more equitable, needs-based services and area improvements.

Access to community resources–where approaches focus on connecting people to community resources and opening up opportunities for social participation and social inclusion. Based on an understanding of the breadth of the voluntary and community (non-governmental) sector (VCS) and its key role in addressing unmet health needs and marginalization (NHS Future Forum, 2011), these approaches establish referral routes, reduce barriers to social participation and volunteering, and commission and coordinate community-based group activities. Reflecting different levels through which participation is supported, the three sub-groups are: Pathways to participation, including social prescribing and other types of non-medical referral systems (Scottish Community Development Centre, 2013); community hubs (Hunter, 2007) and holistic models of community-based commissioning (Cabinet Office Social Exclusion Task Force, 2010).

DISCUSSION

The family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing is broader in scope and more upstream in emphasis compared with other identified typologies, many of which focus on consumer and community involvement in health care (e.g. Oliver et al., 2008; Mittler et al., 2013; Sarrami-Foroushani et al., 2014). Clarity over purpose and attention to process are recurring themes in community participation literature (Cornwall, 2008; Draper et al., 2010). Like Rosato’s recent framework for community interventions in global health (Rosato, 2015), the family reflects these themes in differentiating how approaches work, with reference to available theoretical literature. The theories of change developed by O’Mara-Eves et al. (2013) proved a good starting point, but these were identified from a systematic review drawing mostly on randomized controlled trials from outside the UK. Our approach was more pluralist and whilst the first legitimation challenge of ‘what counts as evidence’ remains contested territory, a more rounded picture was gained because some practice-based evidence was included (Figure 1). Nonetheless, there were limitations with the desk-based review, which included only secondary level evidence and could not map the richness of community practice. As this was a broad topic, we applied a study design filter to increase specificity, thereby reducing the number of irrelevant hits, and included only English language publications. This may have resulted in some relevant review-level evidence being missed, including non-UK sources.

The development process involved stakeholder consultation and, although limited in scope, this was of value in testing the relevance and practical significance of the overall framework. It was not possible to involve communities in this process, except through voluntary sector representatives and this is a major limitation. The family of community-centred approaches was deemed to have good face validity as a typology according to feedback from those in policy, practice and academia. A consistent theme was stakeholders’ preference for the term ‘approaches’ rather than ‘interventions’, as this was considered to encompass ways of working as well as more formal interventions (Preston et al., 2010). Also that while the ‘family’ brought clarity around types of approaches, comprehensive health promotion interventions in practice might operate across more than one category. The family is therefore situated within a body of literature that acknowledges the primacy of process in understanding community participation practice (Laverack, 2006; Draper et al., 2010).

The project aimed to address the lack of shared terminology and a fragmented knowledge base (the second legitimation challenge). The family tree structure was adopted as a visual representation of the range of, and interrelationships between, participatory approaches. This could be viewed as an over simplistic representation, reducing the complexity of participation processes to a ‘menu of interventions’. This was not the intention, although there is a tension between making evidence more accessible by highlighting practical models and ensuring complexity is represented. Our approach has been to create a flexible and inter-linked framework that acknowledges the wealth of UK and international evidence in this field. In other words, attempts to map and define are there to aid the end user navigate and apply evidence, not to impose rigid categorizations. Variations can occur across a number of dimensions, for example, whether the intervention is focused on wider determinants or on individual health behaviours. The scoping review identified a range of international literature covering different populations and types of inequality; however, there is scope to explore the fit of the family when working with specific communities of interest or identity and in socio-cultural contexts outside the UK. A key conclusion is one of pluralism, recognizing the diversity of participatory methods used in health promotion.

Analysis of power is central to many conceptual frameworks on participation (Jolley et al., 2008; Oliver et al., 2008; O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013). We chose not to assess which are or are not ‘empowerment’ approaches because the term is not applied consistently in published literature (Woodall et al., 2012) and empowerment should be core to all community-centred practice. Other aspects of community participation also have significance (Cornwall, 2008) and the decision to use social connectedness as an organizing concept influenced the range of intervention types included, for example befriending and social network approaches. This reflects two sets of arguments: strong evidence on social relations as a major determinant of health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010) and recent debates that social participation should be seen as part of a spectrum of involvement (Piskur et al., 2014).

One major limitation of the family is the exclusion of citizen advocacy and protest (Wallerstein et al., 2011), although the importance of these forms of social action are acknowledged in the guide. Laverack (2012) argues that contemporary health promotion practice needs to engage with health activism. Community-centred approaches should be seen as complementing community-led action and moreover can be used to build alliances around issues of social justice. A critical perspective should be maintained, recognizing that social-political context influences patterns of public participation at the macro-level (Slutsky et al., 2017) and through exclusionary processes driven by inequalities between and within communities.

Application to practice

The project aimed to improve knowledge translation of community participation evidence thereby supporting wider uptake within public health. The publication of the guide was followed by wide dissemination by the two national agencies, NHS England and PHE. Subsequently the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) recommended that health planners, commissioners and practitioners use the family alongside NICE guidance on community engagement. The guide has also informed and influenced policy direction and delivery within the two national agencies. Endorsement of community-centred approaches within national strategy and guidance has helped gain greater recognition of community participation as core to public health. Perhaps more critically, and despite definitional issues, legitimacy has been enhanced through acknowledgement of existing research and identification of practical models. Building transferable learning can help counter the threat of short-term policy cycles to the sustainability of community practice.

The family of community-centred approaches has value as a planning tool to identify evidence-based options for working with communities and addressing community-level determinants of health and wellbeing. The flexible structure, highlighting alternative methods and mechanisms, means it can be applied to a range of health improvement programmes and work with different population groups. In England, we have seen some districts, and also individual community-led organizations, adopting the family as a framework for whole system approaches to working with their local populations. This requires action across all four groups and is consistent with a top-down, bottom-up parallel tracking approach to community empowerment (Laverack, 2011).

There is a potential application to research, primarily as a tool for organizing evidence, which may help in the construction of an evidence base for community participation (Sarrami-Foroushani et al., 2014; Rifkin, 2014). Notwithstanding the UK orientation, particularly in identification of exemplar interventions, the family provides an inter-linked typology that is rooted in an international literature. Transferability would need to be tested, including with communities, but we believe that the family of community-centred approaches does have wider relevance and offers a flexible framework to guide identification of alternative approaches.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This paper has reported on a UK project that sought to draw together and disseminate evidence on community participation to support a shift to a more community-oriented public health system. The development of national guidance led to the introduction of a conceptual framework mapping participatory intervention types, which has helped shape national strategy and local practice. The family of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing comprises four major groups: strengthening communities; volunteer and peer roles; collaborations and partnerships and access to community resources. Whilst there are inherent difficulties applying a retrospective categorization on a field characterized by diversity, we believe that the family provides a flexible framework to help navigate the evidence base and identify potential approaches for working with communities to achieve health goals. Further evaluation is needed to assess the application and impact of this conceptual framework as a planning tool. Its transferability outside the UK needs testing, but hopefully the ‘family tree’ can evolve when applied in other contexts. Acknowledging the breadth and variety of participatory approaches, aligning evidence and providing definitions help address legitimation challenges that undermine wider adoption in health systems. At a community level, taking a pluralist perspective on interventions support the developmental nature of health promotion practice where the best programmes are ones designed with people not for them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The project was initiated and led by JSo, who developed the family of community-centred approaches while on secondment with PHE as an expert advisor. JSt and PM had strategic oversight and contributed to the conceptual development. The scoping review was undertaken by the university team [AMB, KS, JSo]. The authors would like to thank all members of the NHS England and PHE steering group who provided guidance to project. Also Ben Mitchell (Leeds Beckett University) for his contribution to the literature searches. A Briefing and Full report can be found at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-and-wellbeing-a-guide-to-community-centred-approaches. (last accessed 14 November 2017)

FUNDING

This work was supported by Public Health England and NHS England as part of a joint project ‘Working with Communities–Empowerment, Evidence and Learning’, 2014–2015.

REFERENCES

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnall A., Southby K., Mitchell B., South J. (2015). Bibliography and Map of Community-Centred Interventions for Health and Wellbeing. Leeds Beckett University, Leeds: [Online]: http://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/1782/ (last accessed 14 November 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Bracht N., Tsouros A. (1990) Principles and strategies of effective participation. Health Promotion International, 5, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Burton P., Croft J., Hastings A., Slater T., Goodlad R., Abbott J.. et al. (2004) What Works in Area-Based Initiatives? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Report no 53.Home Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office Social Exclusion Task Force, (2010) Inclusion Health: Improving the Way We Meet the Primary Health Care Needs of the Socially Excluded. HM Government, Cabinet Office, Department of Health, London. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2009) Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. University of York, York. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A. (2008) Unpacking ′Participation′: models, meanings and practices. Community Development Journal, 43, 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A. (2010) Engaging Communities for Health Improvement. A Scoping Review for the Health Foundation. The Health Foundation, London. [Google Scholar]

- Draper A. K., Hewitt G., Rifkin S. (2010) Chasing the dragon: developing indicators for the assessment of community participation in health programmes. Social Science and Medicine, 71, 1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durie R., Wyatt K. (2013) Connecting communities and complexity: a case study in creating the conditions for transformational change. Critical Public Health, 23, 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott E. (2012) Connected Comunities. A Review of Theories, Concepts and Interventions Relating to Community-Level Strengths and Their Impact on Health and Well Being. Connected Communities, London. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B. (2011) Community development in health: a literature review. Health Empowerment Leverage Project.

- Foot J., Hopkins T. (2010) A Glass Half Full: How an Asset Approach Can Improve Community Health and Well-Being. Improvement and Development Agency (IDeA; ), London. [Google Scholar]

- Harden A., Sheridan K., Mckeown A., Dan-Ogosi I., Bagnall A. (2015) Review 5: Evidence Review of Barriers to, and Facilitatrors of, Community Engagement Approaches and Practice in the UK. Institute for Health and Human Development, University of East London, London. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney C., Israel B. (2008) Social networks and social support In Glantz K., Rimer B., Viswanath K. (eds), Health Behaviour and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practise. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. B., Layton J. B. (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med, 7, e1000316.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. (2007) Learning from Healthy Living Centres: the changing policy context. Big Lottery Fund Policy Commentary Issue 1. Big Lottery Fund.

- Jolley G., Lawless A., Hurley C. (2008) Framework and tools for planning and evaluating community participation, collaborative partnerships and equity in health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 19, 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge K., Bauld L. (2006) Learning from policy failure? Health Action Zones in England. European Journal of Public Health, 16, 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverack G. (2006) Improving health outcomes through community empowerment: a review of the literature. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 24, 113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverack G. (2011) Parallel-tracking bottom-up approaches within chronic disease prevention programmes. International Journal of Public Health, 57, 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverack G. (2012) Health activism. Health Promotion International, 27, 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S. A., Dick J., Pond P., Zwarenstein M., Aja G., Van Wyk B.. et al. (2005) Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 25, CD004015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. (2010) Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100, S81–S87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. (2012) Introduction to community organizing and community building In Minkler M. (ed) Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare, 3rd edn Rutgers University Press, Newark, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Mittler J. N., Martsolf G. R., Telenko S. J., Scanlon D. P. (2013) Making sense of ‘consumer engagement’ initiatives to improve health and health care: a conceptual framework to guide practice. The Milbank Quarterly, 91, 37–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A., Ziglio E. (2007) Revitalising the evidence base for public health: an assets model. Promotion and Education, 14, 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2016) Community Engagement: Improving Health and Wellbeing and Reducing Health Inequalities . NICE guideline NG 44 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Future Forum. (2011) Choice and Competition. Delivering Real Choice. A Report from the NHS Future Forum. Department of Health, London. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara-Eves A., Brunton G., Mcdaid D., Oliver S., Kavanagh J., Jamal F.. et al. (2013) Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research, 1, 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver S., Rees R. W., Clarke-Jones L., Milne R., Oakley A. R., Gabbay J.. et al. (2008) A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Expectations, 11, 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskur B., Daniels R., Jongmans M. J., Ketelaar M., Smeets R. J. E. M., Norton M.. et al. (2014) Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clincial Rehabilitation, 28, 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston R., Waugh H., Larkins S., Taylor J. (2010) Community participation in rural primary health care: intervention or approach? Australian Journal of Primary Health, 16, 4–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England and NHS England. (2015) A Guide to Community-Centred Approaches for Health and Wellbeing. London, Public Health England. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael D., Bryant T. (2002) The limitations of population health as a model for the new public health. Health Promotion International, 17, 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Realising the Value. (2016) At the Heart of Health Realising the Value of People and Communities. The Health Foundation, NESTA, London. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes S. D., Foley K. L., Zometa C. S., Bloom F. R. (2007) Lay health advisor interventions among hispanics/latinos: a qualitative systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, 418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin S. B. (2014) Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes: a review of the literature. Health Policy and Planning, 29, ii98–ii108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosato M. (2015) A framework and methodology for differentiating community intervention forms in global health. Community Development Journal, 50, 244–263. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrami-Foroushani P., Travaglia J., Debono D., Braithwaite G. (2014) Key concepts in consumer and community engagement: a scoping meta-review. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Community Development Centre. (2013) Assets Based Approaches to Health Improvement–Creating a Culture of Thoughtfulness, Briefing Paper. SCDC, Glasgow. [Google Scholar]

- Slutsky J., Tumilty E., Max C., Lu L., Tantivess S., Curu Haugen R.. et al. (2017) Patterns of public participation: opportunity structures and mobilization from a cross-national perspective. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 30, 751–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South J., Meah A., Bagnall A.-M., Jones R. (2013) Dimensions of lay health worker programmes: results of a scoping study and production of a descriptive framework. Global Health Promotion, 20, 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springett J., Owens C., Callaghan J. (2007) The challenge of combining ′lay′ knowledge with ′evidenced-based′ practice in health promotion: fag ends smoking cessation service. Critical Public Health, 17, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- SQW Consulting. 1 Main Report. (2011) Communities in the driving seat: a study of Participatory Budgeting in England: Final report. London, Department of Communities and Local Government.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2015) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide. [Google Scholar]

- The Marmot Review. (2010) Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. London, The Marmot Review.

- Trickett E. J., Beehler S., Deutsch C., Green L. W., Hawe P., Mcleroy K.. et al. (2011) Advancing the science of community-level interventions. Amercian Journal of Public Health, 101, 1410–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. (2002) Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 30, 72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Mendes R., Minkler M., Akerman M. (2011) Reclaiming the social in community movements: perspectives from the USA and Brazil/South America: 25 years after Ottawa. Health Promotion International, 26, ii226–ii236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall J., Warwick-Booth L., Cross R. (2012) Has empowerment lost its power? Health Education Research, 4, 742–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2007) Community Health Workers: What Do We Know About Them. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (2012) Health 2020: a European policy framework supporting action across government and society for health and well-being. Copenhagen.

- World Health Organization. (2016) Shanghai Declaration on Promoting Health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Shanghai. Geneva, World Health Organization. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yerbury H. (2012) Vocabularies of community. Community Development Journal, 47, 184–198. [Google Scholar]