Abstract

Despite promising decreases in overall smoking rates, a significant proportion of the population continue to engage in this costly behavior. Substituting e-cigarettes for conventional cigarettes is an increasingly popular harm-reduction strategy. Narratives may be one method of increasing the substitutability of e-cigarettes. Participants (N = 160) were assigned to one of four narratives that described a close friend becoming ill. In the Positive narrative, participants read about a friend that became ill but learned it was only the flu. In the Negative narrative, the friend became ill from smoking cigarettes, in the Negative-Regret narrative, the friend became ill from smoking cigarettes and explicitly expressed regret for having started smoking, and in the Negative-Change narrative, the friend became ill from smoking, switched to e-cigarettes and made a full recovery. Participants then completed an experimental tobacco marketplace (ETM) where they could purchase conventional cigarettes and alternative nicotine products including e-cigarettes. Across ETM trials, the price of conventional cigarettes increased while the price of the alternative products remained constant. Initial purchasing of conventional cigarettes decreased and initial purchasing of e-cigarettes increased in the Negative-Change group compared to the other three groups. This finding was moderated by conventional cigarette dependence and perception of e-cigarette risk but not previous e-cigarette exposure. Narratives can change conventional cigarette and e-cigarette purchasing in an ETM that mimics real-world marketplaces. Narratives can be a valuable harm-reduction tool because they are cost-effective, can be widely disseminated, and can be personalized to individuals.

Keywords: narratives, harm-reduction, demand, behavioral economics, experimental tobacco marketplace

Despite historically low levels of cigarette smoking, cigarettes continue to cost billions in health-care and lost productivity and are a leading cause of preventable deaths (Jamal et al., 2015; Xu, Bishop, Kennedy, Simpson, & Pechacek, 2015; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2014). Due to high societal costs, methods of reducing or eliminating cigarette smoking are of great importance. Though the goal of the majority of interventions is cessation, interest in harm-reduction methods is growing (Phillips, 2009; Royal College of Physicians of London, 2007). Harm-reduction methods include any change that reduces exposure to toxicants from tobacco products either by modifications of smoking behavior or adoption of an alternative nicotine product (Phillips, 2009). Note that this does not necessarily entail eliminating nicotine use. Even a “small” reduction (e.g., 10%) in smoking behavior at the population level as a result of harm reduction methods would result in tens of billions of saved health care costs (Lightwood & Glantz, 2016).

Substituting electronic cigarettes (e-liquid or disposable e-cigarettes) for conventional cigarettes is increasingly discussed as a harm-reduction method both in research and practice (Levy et al., 2017; Polosa, Rodu, Caponnetto, Maglia, & Raciti, 2013; National Academies of Science, 2018). Substitution is defined as the increased purchasing of a fixed-price product as the price of an alternative product increases (Hursh 1980; Johnson & Bickel 2003; Green & Freed 1993). In this context, if purchases of e-cigarettes at a fixed price increased as a result of increasing conventional cigarette prices, then e-cigarettes have functioned as a substitute. According to the economic definition of substitution, declines in purchasing of the increasing-price product are not necessary (Kroon 2007). However, if the substitution were to have a harm reduction effect, then conventional cigarette purchasing should also decline. Evidence does exist to suggest that e-cigarette substitution can reduce conventional cigarette consumption (Rahman, Hann, Wilson, Mnatzaganian, & Worrall-Carter, 2015) and prospective models of e-cigarette harm-reduction methods suggest that e-cigarette substitution could result in substantial financial and health benefits (Soneji, Sung, Primack, Pierce, & Sargent, 2018).

One way to engender harm reduction entails the use of narratives. Narratives are stories that present information in a persuasive and meaningful way. Narrative theory posits that as a social species, humans are especially equipped to be influenced by the experiences or decisions of others through stories (Bickel et al., 2017). A meta-analysis by Winterbottom and colleagues provided evidence that narratives can change decision-making by increasing the persuasiveness of a message (Winterbottom, Bekker, Conner, & Mooney, 2008). For example, Nummenmaa and colleagues found that the use of narratives resulted in greater utilization of information compared to presentations of information only (Nummenmaa et al., 2014). Additionally, narratives may be personalized to the individual such as matching demographic characteristics between the narrative subject and the target of the narrative. Such personalization has been demonstrated to improve the efficacy of narratives (Hirsh et al. 2012; Lu 2013).

Narratives have been demonstrated to be more effective than information alone at improving health-related decision-making in real-world settings including mammogram (Kreuter et al., 2010) and cervical cancer (Murphy et al., 2015) screenings in women, colon cancer screenings (Dillard, Fagerlin, Dal Cin, Zikmund-Fisher, & Ubel, 2010), scheduling vaccinations (Frank, Murphy, Chatterjee, Moran, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2015), workplace safety (De Wit, Das, & Vet, 2008; Kiene & Barta, 2003), driving under the influence of alcohol (Moyer-Gusé, Jain, & Chung, 2012), and safer sex practices (Kiene & Barta, 2003).

Narratives have also been effective at targeting health-related decision-making in the laboratory. This is especially valuable as narrative effectiveness can be tested and validated before real-world applications. Quisenberry and colleagues presented participants with narratives related to a friend contracting a sexually transmitted infection (STI) after engaging in risky sex (Quisenberry, Eddy, Patterson, Franck, & Bickel, 2015). Participants were then asked to identify pictures of individuals with whom the participant would be willing to have casual sex or who would be most likely to have an STI. Participants made choices about engaging in unprotected sex now or condom-protected sex later with the individuals from the images. The authors found a decrease in impulsive choice (specifically, less likely to engage in unprotected sex with an individual with an STI) in the groups that read negative health outcome narratives. Additionally, participants who read a narrative with a negative health outcome in which their friend explicitly expressed regret for their decision to have unprotected sex were less likely to engage in unprotected sex with an individual regardless of STI status.

Importantly, narratives have proven effective in reducing cigarette smoking. The Center for Disease Control’s ad campaign “Tips From Former Smokers” targeted cigarette smoking using narratives (CDCTobaccoFree, 2017). Various media ads (e.g., TV commercials, public transportation, internet) were released that depicted individuals who have experienced negative health consequences of smoking as well as individuals who have experienced health improvements after quitting (Neff et al., 2016). Neff found these narratives were effective in increasing both quit attempts and quit successes since the campaign began in 2012.

One recently developed laboratory measure, the Experimental Tobacco Marketplace (ETM), is acutely capable of investigating the effects of narratives on conventional cigarette and e-cigarette purchasing (Bickel et al., 2018; Quisenberry, Koffarnus, Hatz, Epstein, & Bickel, 2016). In the ETM, participants can choose from different simultaneously available nicotine products (e.g., conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, snus). Across trials, the price of conventional cigarettes is increased while the price of alternative nicotine products remains constant. Using the ETM, Quisenberry and colleagues (Quisenberry et al., 2016) found that cigarillos, e-cigarettes, and chewing tobacco functioned as substitutes for conventional cigarettes and Snider, Cummings, and Bickel (Snider, Cummings, & Bickel, 2017) found that e-cigarette substitution was greatest in individuals who already used e-cigarettes daily or weekly. Heckman and colleagues (Heckman et al., 2017) found that e-cigarette substitution was greatest in participants who smoked fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. These ETM results are promising but implicate conventional cigarette prices and prior e-cigarette exposure as drivers of substitution. Given that these factors may be difficult to control, other methods of increasing the substitutability of e-cigarettes such as narratives, independent of increased conventional cigarette prices or previous exposure to e-cigarettes, are important.

What effect narratives have on the purchasing of different nicotine products and if explicitly encouraging harm-reducing behaviors increases purchasing e-cigarettes in the ETM is unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate several variants of a personalized narrative to determine which would engender substitution and lead to decreases in the purchasing of conventional cigarettes in the ETM. We hypothesized that a personalized narrative that models the most appropriate behavior and its consequences would promote the greatest harm reduction response. Additionally, we sought to investigate if personalized narratives would reduce delay discounting, a behavioral economic measure of impulsivity relevant to cigarette smoking (Bickel, Odum, & Madden, 1999; Friedel, DeHart, Madden, & Odum, 2014).

Methods

Procedure

Demographics and Tobacco Product Use

One hundred and sixty participants (81 males, 77 females, 2 other) were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk and paid $7.50 to complete an approximately one-hour online survey administered through Qualtrics survey software. The sample size was determined by an a priori power analysis (Power = 0.80, medium effect size of 0.25). The Amazon Mechanical Turk participant pool was limited to workers that lived in the USA, were 21 years or older and had an approval rating of at least 95% meaning that their work was deemed as acceptable for 95% of their submissions. All participants reported smoking at least 10 cigarettes a day. Participants first completed a series of demographic questions and reported nicotine product use in a Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992). Participants also completed the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD; Fagerström 2012) and reported their perceived risk of different nicotine products (Mooney, Leventhal, & Hatsukami, 2006). Participants were not de-briefed as to goals of the experiment or their narrative condition upon completing the experiment. The Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board approved all procedures and protocols and consent was implied with submission of the online survey.

Experimental Tobacco Marketplace

The ETM provided participants with the opportunity to purchase hypothetical nicotine products, constrained by a budget based on their typical number of nicotine products used per day (M = $28.63, SD = $22.92). Participants could not purchase more products than their budget allowed (Quisenberry et al., 2016). The prices of the nicotine products for calculation of the budget and for some of the conditions when purchasing products within the ETM were based on prior studies (Quisenberry, Koffarnus, Epstein, & Bickel, 2017; Quisenberry et al., 2016); specifically, prices were: single cigarette = $0.25, single piece of gum = $0.80, single pouch of chew = $0.20, single disposable e-cigarette = $9.99, 1 ml bottle of e-cigarette liquid = $0.89, single pouch of snus = $0.20, and single lozenge = $0.60.

Participants completed seven ETM trials. For each trial, the price of conventional cigarettes increased ($0.06, $0.13, $0.25, $0.50, $1.00, $2.00, $4.00) while prices of the other nicotine products were held constant. Participants were instructed to purchase as many products as they wished and imagine that they would keep any unspent budget. The nicotine content for each product was displayed and a brief description of the product was provided.

Narratives

Before participants completed the ETM, they were randomly assigned to read one of four brief narratives (see Supplemental Material): Positive, Negative, NegativeRegret, NegativeChange. These narratives were modeled after the narratives used in Quisenberry et al. (2015) that proved effective at altering delay discounting. Additionally, the narratives were developed through the framework of Narrative Theory (Bickel et al. 2017), which indicates that personally-specific and vivid narratives are most effective at changing behavior. All four narratives depicted a friend of similar age and gender to the participant, who fell ill (e.g., nausea, headaches) and visited their physician. In the Positive narrative, the doctor informed the friend that they had the flu and the friend was relieved. In the three negative narratives, the friend was informed that their illness was due to a high amount of blood toxins caused by cigarette smoking and was distraught over the diagnosis. In the NegativeRegret narrative, the friend explicitly expressed regret for having started smoking. In the NegativeChange narrative, the friend stopped smoking and began using e-cigarettes, which resulted in lower blood toxins and improved health, leading to an expression of gratitude for substituting e-cigarettes for conventional cigarettes. After reading each narrative, participants were asked as an attention check to report if the friend just had the flu, was very sick, or was very sick but recovering. All participants correctly identified the outcome of their assigned narrative. The Flesch-Kincaid reading comprehension scores for the four narratives ranged between grade 7.5 and 9.2 (Kincaid, Fishburne, Rogers, & Chissom, 1975).

Delay Discounting

Participants completed four, five-trial adjusting delay-discounting tasks before and after narrative group assignment: money-only, cigarettes-only, money-now or cigarettes-later, and cigarettes-now or money-later (cross-commodity discounting; (Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014). For each delay-discounting task, the Effective-Delay 50 (ED50) was sought; that is, the delay at which the outcome is valued at half of its full value (Yoon & Higgins, 2008). This was accomplished by fixing the smaller and larger outcomes (at $50 and $100, in money or equivalent number of cigarettes) and adjusting the delay between them (i.e., the delay increased or decreased depending on if the participant chose the delayed or immediate outcome in the previous trial, respectively). ED50 is transformed to obtain the k parameter from the hyperbolic model of delay discounting (ED50 = 1/k; Mazur, 1987), which describes how value decreases as a function of delay. k is used over ED50 for subsequent analyses by convention and in line with our previous work. For the cigarette-only and cross-commodity discounting tasks, the number of cigarettes presented in the task was estimated by initially asking participants how many cigarettes were worth $100 to them (M = 335, SD = 26). Additionally, participants were asked two attention check questions that were interspersed between the four delay-discounting tasks before reading the narratives. The first question asked participants if they would prefer $50 now or $100 now and the second question asked if they would prefer an amount of cigarettes equivalent to $50 or an amount of cigarettes equivalent to $100 (based the participant’s report of how many cigarettes was worth $100 to them). Participants also answered the $50 now or $100 now attention check question after narrative group assignment. Participants did not answer the cigarette attention check question after the narrative group assignment. All participants choose the larger of the two amounts for both questions. These attention checks, in part, serve to validate the participant responses.

Data Analysis

All measures and participant data were included in the analyses. The number of nicotine products purchased in each ETM trial was converted to a proportion of total dollars spent in that trial. Previous ETM studies have used mg of nicotine purchased as the dependent variable, however, the proportion of total dollars spent was preferred, primarily because participants may not have had experience with all products (Snider et al., 2017). For example, a 12mg/2mL bottle of e-liquid would deliver approximately as much nicotine as a pack of cigarettes, but without direct experience of each product, participants may not be assumed to be aware of these conversions. Participants spent an average of 93% (range: 89% - 96%) of their total budget in each trial.

The exponentiated demand equation was fitted to the cigarette purchase results (Koffarnus, Franck, Stein, & Bickel, 2015):

| (1) |

where 𝒬 is the proportion of dollars spent on cigarettes at a given price, C is the price of the cigarette, Q0 represents demand intensity or the model fit y-intercept (e.g., purchasing at zero cost; upper bound set to 1), k is a constant and is the range of the function in logarithmic units (obtained from the empirical range + 0.5; set to 0.818 in these analyses), and ⍺ represents demand elasticity or the decrease in purchasing as price increases. Demand curves were fitted using the beezdemand package in R (Kaplan, 2018).

Substitution for conventional cigarette alternatives was measured by fitting a linear regression line to alternative nicotine product purchases as a function of conventional cigarette price. The y-intercept term represents the purchasing of the alternative at zero conventional cigarette cost. The slope of the regression represents substitutability of that alternative, with positive slopes indicating substitution. Model fit parameters for both conventional cigarettes and their alternatives were compared using the least-square means differences (MD) between the parameter estimates using the lsmeans package in R (Lenth, 2016). Least-square means are means that have been adjusted for additional model covariates. False discovery rate adjustments were used for all pairwise comparisons.

Delay-discounting task results were analyzed using a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE). The output of GEE analyses are interpreted similarly to standard regression output including a β value but has been adjusted to account for clustering within groups (actual clustering was minimal (Hox, Moerbeek, & van de Schoot, 2010). GEE analyses were performed in R using the gee package (Carey, 2015).

Results

Demographics and Tobacco Product Use

Participants were 51% male, 83% Caucasian, had a mean age of 35.74 years (SD = 10.33), and had 13.23 (SD = 1.33) years of education. Participants also reported smoking 20.65 (SD = 36.98) cigarettes per day and had a mean FTCD score of 10.89 (SD = 1.38), indicating high cigarette dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). Results of the TLFB revealed that in the past 30 days 25% used e-cigarettes, 7% used nicotine gum, 4% used chewing tobacco, 2% used nicotine lozenges, and less than 1% of participants used snus. Demographics and product use were similar among the four narrative groups. Table 1 reports the complete description of participant demographics and tobacco product use. Chi-square tests for independence for comparing nominal variables and ANOVA analyses for continuous variables did not reveal any statistically significant differences in demographics or tobacco product use between groups (ps >.05).

Table 1.

Group demographics and nicotine product use.

| Positive (n=40) |

Negative (n= 40) |

NegativeRegret

(n=40) |

NegativeChange

(n=40) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 35.95 (1.49) | 39.79 (1.97) | 33.58 (1.97) | 33.79 (1.54) |

| Education (years) | 14.23 (1.45) | 13.35 (2.01) | 13.87 (1.59) | 13.58 (1.89) |

| Employment Status (employed) | 91% | 78% | 90% | 83% |

| Gender (female) | 39% | 65% | 53% | 50% |

| Income | $45,430 ($3,820) | $43,910 ($3,528) | $35,622 ($2,818) | $34,846 ($3,390) |

| Race (Caucasian) | 76% | 88% | 83% | 88% |

| Relationship Status (married or cohabitating | 53% | 70% | 58% | 73% |

| Daily Nicotine Product Use | ||||

| Chew (single pouch) | 0.34 (0.26) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.73 (0.63) | 0.27 (0.25) |

| Conventional Cigarettes (single) | 16.93 (1.46) | 20.38 (1.34) | 16.13 (1.27) | 19.32 (3.51) |

| Disposable E-cigarettes (single) | 0.24 (0.22) | 0.20 (0.13) | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.27 (0.14) |

| mL of E-liquid (12mg/2mL) | 0.88 (0.53) | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.50 (0.38) | 0.83 (0.41) |

| Nicotine Gum (single piece) | 0.78 (0.73) | 0.38 (0.26) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.37 (0.25) |

| Nicotine Lozenge (single piece) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Snus (single pouch) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.02) |

Note. Values in parentheses are standard errors for that group.

Participants were also asked to rate the risk of consuming snus, nicotine gum, and e-cigarettes in comparison to conventional cigarettes. Most participants rated snus as having as many toxins (78% of participants) and equally likely to cause cancer (77%) as conventional cigarettes. The majority of participants rated both nicotine gum and e-cigarettes as having fewer toxins (73% and 70%, respectively), less likely to cause cancer (73%, 70%), and less likely to cause heart disease (82%, 66%) or lung disease (82%, 67%) than conventional cigarettes. However, the majority of participants rated snus (88%), nicotine gum (64%), and e-cigarettes (88%) as being as addictive as conventional cigarettes.

ETM

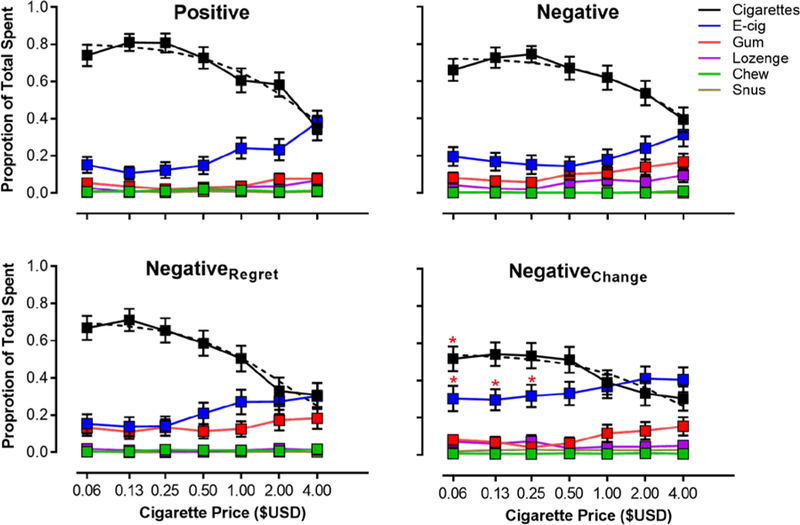

The effects of the narratives on conventional cigarette purchasing between groups were analyzed by comparing Q0 and ⍺ (derived from Equation 1; Koffarnus et al., 2015) using linear regression (Figure 1). Group means and individual purchasing values from the Equation 1 model fit are reported in the Supplemental Material. A significant main effect for narrative group (β = −0.523, p < .05) was found for Q0, indicating that intensity of demand for conventional cigarettes was different between groups. Post hoc tests of Q0 for the NegativeChange group was significantly lower than the other three narratives (Positive MD = 0.273, p < .01; Negative MD = 0.259, p < .01; NegativeRegret MD = 0.218, p < .05), indicating this group displayed lower initial purchasing of conventional cigarettes. Additionally, a significant interaction of narrative group and FTCD scores (β = 0.042, p < .05) was found, indicating that the NegativeChange narrative was less effective in heavy smokers in reducing cigarette demand intensity. Differences in ⍺ among narrative groups were not detected, suggesting that the rate of decrease in conventional cigarette purchasing as a function of price did not differ between groups.

Figure 1.

ETM results for each narrative group. Dotted black lines depict the Equation 1 model fit to proportion of total spent on cigarettes at each cigarette price point. x-axis is scaled in log units. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the other narrative groups.

The effects of the narratives on e-cigarette purchasing were analyzed by comparing the intercepts and slopes from the linear regression models fitted to e-cigarette purchasing. A significant main effect for narrative group on the model intercept was found (β = 0.066, p < .001) demonstrating that initial e-cigarette purchasing differed between groups. The model fit intercept for the NegativeChange narrative was significantly larger than the other three narratives (Positive MD = 0.189, p < .05; Negative MD = 0.155, p < .05; NegativeRegret MD = 0.149, p < .05) indicating that participants reading the NegativeChange narrative spent more on e-cigarettes than the other narrative groups at the lowest cigarette price.

Main effects for e-cigarette use (β = 0.036, p < .001) and the perception of risk of e-cigarettes (β = −0.002, p < .05) were also found. Specifically, e-cigarette purchasing was higher in participants with previous history of e-cigarette use and lower perceptions of e-cigarette risk in all narrative conditions. No significant interactions with narrative assignment were found. Therefore, e-cigarette use and perception of risk of e-cigarettes did not influence the degree to which the NegativeChange narrative affected initial e-cigarette purchasing.

The mean regression model slope of e-cigarettes was positive for all four groups (Positive β = 0.064, Negative β = 0.038, NegativeRegret β = 0.041, and NegativeChange β = 0.028), meaning that e-cigarettes served as a substitute as the price of conventional cigarettes increased, but these slopes were not significantly different between the four narratives. Therefore, while initial e-cigarette purchasing was affected by the NegativeChange narrative, the effect of conventional cigarette price on e-cigarette purchasing was not. However, comparisons of e-cigarette purchasing at each price revealed that purchasing was higher in the NegativeChange group at the $0.06 (p < .05), $0.13 (p < .05) and $0.25 (p < .05) prices compared to the other three groups.

Delay Discounting

Results of the delay-discounting tasks (natural log-transformed k) were analyzed using GEE analyses. A statistically significant main effect for delay-discounting task commodity (β = 0.801, p < .01) was found. Although, no significant main effects for task completion before or after exposure to the narratives (β = 0.102, p > .05) or narrative assignment (β = 0.292, p > .05) were found, several planned pairwise comparisons were found.

Pairwise comparisons revealed several significant changes in delay discounting. The discounting of money now versus cigarettes later increased in the NegativeChange group (MD = −1.362, p < .05) meaning that after reading the narrative, participants more frequently chose a smaller amount of money now over a larger amount of cigarettes later. However, delay discounting in this group was lowest at pre-narrative than the other three groups. Therefore, while the NegativeChange group displayed a significant increase in delay discounting, lnk was not different among the four groups post-narrative. Also, the NegativeChange group discounted cigarettes more in the cigarettes-only task post-narrative than the Positive group both pre and post-narrative (MD = −1.505, p < .05; MD = −1.452, p < .05). Finally, the NegativeRegret group also more frequently chose an immediate amount of money over a larger amount of cigarettes post-narrative compared to the Positive group (MD = −1.832, p < .05). These results suggest that the NegativeRegret and NegativeChange narratives were effective at reducing how participants valued delayed cigarettes.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of narratives in promoting harm-reduction (e.g., increasing the substitutability of e-cigarettes) in the ETM. The results of this study further demonstrate that narratives can be an effective tool in targeting health-related behaviors. Three key findings will be discussed: 1) demand intensity for cigarettes was lowest in the NegativeChange narrative group, 2) e-cigarette purchasing at the lowest conventional cigarette prices was also largest in this group, and 3) this narrative was effective in changing discounting when cigarettes were the delayed option but had no effect in other discounting tasks.

First, we found that the demand intensity for conventional cigarettes (Q0) for participants who read the NegativeChange narrative was lowest among groups. Participants who read this scenario purchased fewer cigarettes at the lowest cigarette price. The narrative was most effective at decreasing conventional cigarette demand intensity in lighter smokers, with participants who reported lower FTCD scores purchasing fewer cigarettes. Interestingly, the NegativeChange narrative only affected demand intensity and not elasticity. One explanation for this result is that the narratives did not differentially reduce the value of cigarettes but increased the value of e-cigarettes in the ETM.

Second, participants in the NegativeChange group purchased more e-cigarettes at the lowest conventional cigarette price and e-cigarette purchasing overtook conventional cigarette purchasing at a lower cigarette price compared to the other three narratives. This pattern held true for the three lowest conventional cigarette price trials. Consistent with previous research (Snider et al., 2017), everyday e-cigarette use predicted initial e-cigarette purchasing among the four groups. However, everyday e-cigarette use did not moderate the impact of narratives. Importantly, these results suggest that regardless of personal history with e-cigarettes, the NegativeChange narrative consistently increased initial e-cigarette purchasing. Narratives, therefore, may serve as an effective behavior change technique that could be targeted at a broad range of users.

Across all four narrative groups, the increase in e-cigarette purchasing as a function of the increase in conventional cigarette price was similar. The change in the initial purchasing of e-cigarettes may represent a change in the value of e-cigarettes, independent of the price of conventional cigarettes. Current definitions of a substitute are limited in their ability to account for a change in alternative product purchasing at the price of the lowest fixed-price alternative (Hursh, 1980; Hursh, 1984; Johnson & Bickel, 2003; Green & Freed, 1993). Some parallels do exist in how demand for a price-manipulated commodity and substitution of a fixed-price commodity are analyzed. The point of comparability is the slope of the function, elasticity of demand in the price-manipulated commodity and cross-price elasticity in the fixed-price commodity, which reflects purchasing sensitivity to the manipulated prices. However, missing from current analytical approaches for behavioral economics is a comparable statistic for measuring the degree of substitution of the fixed-price commodity at the lowest price of the manipulated-price commodity. This is an important oversight because, as evidenced in the results, a decrease in the initial purchasing of conventional cigarettes and an increase in the initial purchasing of e-cigarettes, independent of future changes in conventional cigarette prices would result in important public-health improvements. We propose incorporating initial intensity of substitution (i.e., y-intercept of model fit to the fixed-price commodity) as an additional measure of interest and part of a broader, more reflective understanding of substitutability.

We also found that a modest percentage of participants (20% or more) reported e-cigarettes and even nicotine gum as equally risky as conventional cigarettes across a variety of risk factors before narrative assignment. Perception of e-cigarette risk did predict initial e-cigarette purchasing but did not moderate the effectiveness of the narratives. Changes in risk perception due to the narratives could provide a possible mechanism for understanding why the narrative was effective for some participants. Research has demonstrated that e-cigarette risk perception is a key predictor of e-cigarette use (Farsalinos, Romagna, & Voudris, 2015). If e-cigarettes are to become an effective conventional cigarette harm-reduction tool, disseminating accurate information regarding the true risks of e-cigarettes is essential. Importantly, narratives could serve as a more effective tool for accomplishing this change in risk perception than information alone (Nummenmaa et al., 2014).

Finally, delay discounting of cigarettes in the NegativeChange narrative also changed compared to other narratives. In the cigarettes-only delay-discounting task, these participants more frequently chose a smaller, immediate amount of cigarettes compared to a larger delayed amount of cigarettes, relative to the Positive group. Additionally, participants who read the NegativeChange narrative were more likely to choose a smaller, immediate amount of money over a larger, delayed amount of cigarettes post-narrative. The results of the delay-discounting tasks support the results of the ETM in that the NegativeChange narrative reduced the value of cigarettes. However, no change in monetary discounting was observed (i.e., no statistically significant main effect of the NegativeChange narrative on delay discounting). The unequal effects of the NegativeChange narrative on discounting suggest that the narrative’s effects were domain specific. The Reinforcer Pathology Theory of substance use (and other maladaptive behaviors) integrates delay discounting and demand (i.e., value; purchasing in the ETM) into a parsimonious framework that can account for domain specific changes to delay discounting (Bickel et al. 2014; Bickel et al. 2017). Individuals that excessively value a preferred commodity and prefer immediate, smaller outcomes to delayed, larger outcomes are said to exhibit a reinforcer pathology and this pattern frequently delineates substance users and non-users (Reynolds 2006). Decreasing the relative value of cigarettes through narratives can intervene on this reinforcer pathology (Bickel et al. 2017) as demonstrated in the delay-discounting task and ETM results. These findings support previous research that demonstrates interventions on delay discounting can be limited to the domain of the intervention and not change overall discounting (Green & Lawyer 2014; Hendrickson and Rasmussen 2017; Mahoney & Lawyer 2018).

Therefore, while choosing the smaller, immediate amount of an outcome is typically labeled as “impulsive” (Odum, 2011), in the context of these results, choosing the smaller, immediate outcome may also be viewed as an increase in self-control as participants chose smaller quantities of cigarettes or no cigarettes. More participants reached the upper bound of lnk values (lnk = 24) after reading their assigned narrative in the cigarettes and money now, cigarettes later delay-discounting tasks, indicating greater preference for the immediate outcome (e.g., fewer cigarettes or money respectively) though these increases were not statistically different for any narrative group (cigarette discounting X2 = 0.862, p = .835; money now, cigarettes later discounting X2 = 2.207, p = .531). The five-trial adjusting delay-discounting task (Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014) assumes a hyperbolic discounting function by adjusting the delay to the larger outcome along a hyperbolic curve and does not necessarily identify non-systematic patterns of responding. Similar patterns of exclusive choice in delay-discounting tasks that obtain multiple indifference points would not reflect a hyperbolic function and therefore these results would be ruled as “nonsystematic” (Johnson & Bickel, 2008). Consequently, conceptualizing choosing a smaller, sooner outcome over a larger, delayed outcome when the outcome can lead to maladaptive consequences (e.g., cigarettes) as self-controlled may be possible with a more nuanced understanding of impulsive decision-making These exclusive choice patterns may reflect an important and real change in the value of conventional cigarettes despite not following conventional models of delay discounting. Future research should explore this more nuanced approach to impulsivity and how domain specific changes to delay discounting affect decision-making using delay-discounting tasks that obtain a larger number of indifference points.

One limitation should be addressed in order to improve our understanding of the effectiveness of narratives at changing health behavior. This study asked participants to purchase hypothetical products in the ETM whereas other studies have used potentially-real or real outcomes. The use of hypothetical tasks is especially important to consider when asking e-cigarette naïve participants (75% of study sample) to purchase e-cigarettes. Typically, assessing demand requires experience with the reinforcing effects of an outcome. Participants may be unfamiliar with how many disposable e-cigarettes or mL of e-liquid are required to effectively replace conventional cigarettes and therefore purchased e-cigarettes based on their expectations of the products and not actual experience. Previous research has indicated that demand for real and potentially-real outcomes is different from hypothetical outcomes, yet purchasing of real or potentially-real outcomes and hypothetical outcomes are strongly correlated (Wilson, Franck, Koffarnus, & Bickel, 2016). Consequently, an increase in purchasing of e-cigarettes in naïve users in the NegativeChange group may reflect an increase in the participant’s willingness to sample e-cigarettes which could result in substitution and less conventional cigarette consumption. Future research should use narratives to change purchasing behavior using real or potentially-real outcomes, particularly in naïve e-cigarettes users.

A second limitation of using narratives in hypothetical scenarios related to the high percentage of e-cigarette naive participants is demand characteristics. Participants in the NegativeChange group may have purchased more cigarettes because they believed that was what the experimenters desired. Of note however, demand characteristics did not appear to affect cigarette purchasing in the Negative and NegativeRegret conditions in which expectations of reducing cigarette purchasing could also be extrapolated. Cigarette purchasing in the Negative and NegativeRegret groups did not differ from the Positive group (in which demand characteristics are not a concern), providing some evidence that these results are not due to demand characteristics. Notwithstanding, future research should include information only control conditions as well as additional controls for demand characteristics.

A final limitation, and a limitation of collecting data through Amazon Mechanical Turk in general, is that our sample may not accurately reflect the general smoking population. Our sample was predominantly Caucasian, middle-aged individuals with at least some post high-school education and a mean income greater than poverty levels. This sample is not abnormal for Amazon Mechanical Turk (Huff & Tingley, 2015) but may not fully reflect the general population of cigarette smokers who tend to report lower incomes, less education, and are more racially diverse (CDCTobaccoFree, 2018). Note however, that income, education, and employment did not predict cigarette consumption or e-cigarette consumption in the Timeline Followback nor did they predict cigarette and e-cigarette risk perception or product purchasing in the ETM. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of our narratives on a more representative sample of smokers is unknown and this question should be explored further.

One unique component of the narratives in this study is that they were personalized (matched on age and gender of friend) and directed toward the participant (i.e., second person perspective). This is different from other health-behavior targeted narratives that recount a story in the third person perspective and are not personalized to the reader, such as the “Tips from Former Smokers” narratives (CDCTobaccoFree, 2017). Narratives describing a “similar other” may increase behavior change efficacy by increasing the relevance of both the problem behavior and the behavior change (Hirsh et al. 2012; Lu 2013), as well as increasing the vividness of the scenario (Centola, 2011).

These results further demonstrate the value of the ETM in understanding the substitutability of conventional cigarette alternatives. In a follow-up study (see Supplemental Materials), a similar sample of Mturk workers were assigned to read either the Positive or NegativeChange and completed conventional cigarette and e-cigarette purchase tasks along with the ETM. In the purchase tasks, only one product was presented and participants were asked to purchase the product at a variety of prices. Narrative condition had no effects on conventional cigarette or e-cigarette purchasing in the purchase tasks but purchasing in the ETM differed between groups, similarly to what is reported here. Previous research has similarly demonstrated that demand and substitution is best investigated in a more complete context where all products are available simultaneously (Shahan, Bickel, Madden, & Badger, 1999; Petry, 2001; Stein, Koffarnus, O’Connor, Hatsukami, & Bickel, 2017). For example, Petry (2001) found differential patterns of psychoactive substance (e.g., cocaine, Valium) substitution in alcohol abusers depending on which outcome’s price increased and which outcomes were presented as fixed-price alternatives. The results of the present experiment further demonstrate that choice is in part determined by the context of alternatives. We believe the ETM paradigm presents a valuable tool for understanding the relationship among nicotine products (Bickel et al., 2018).

Importantly, the purpose of this study was not to establish e-cigarettes as a safe and effective harm-reducing alternative to conventional cigarettes. Instead, the purpose of this study was to demonstrate that a narrative intervention could be effective at promoting harm-reducing behavioral change with e-cigarette substitution as a specific example. While some evidence exists that e-cigarette substitution may be an effective harm-reduction strategy (Lightwood & Glantz 2016; Levy et al. 2017), more research is clearly needed. The ETM provides an effective forum for testing narrative effectiveness and this model could be extended to other harm-reduction or cessation interventions. For example, future research could develop narratives that encourage substitution of nicotinized gum or lozenges in the ETM. Narratives could also be used to target smoking cessation or to decrease the substitutability of e-cigarettes.

We demonstrated that narratives encouraging harm-reduction can increase the substitutability of e-cigarettes and decrease conventional cigarette purchasing. Narratives can be widely disseminated to many individuals through public spaces such as the internet and television. Narratives are also cost-effective in that they do not require administration by a trained professional. Finally, narratives can be personalized and modified to include specific information that is meaningful to the reader. In sum, narratives present a promising avenue for effective health-related behavior change and specifically harm reduction through e-cigarette substitution.

Supplementary Material

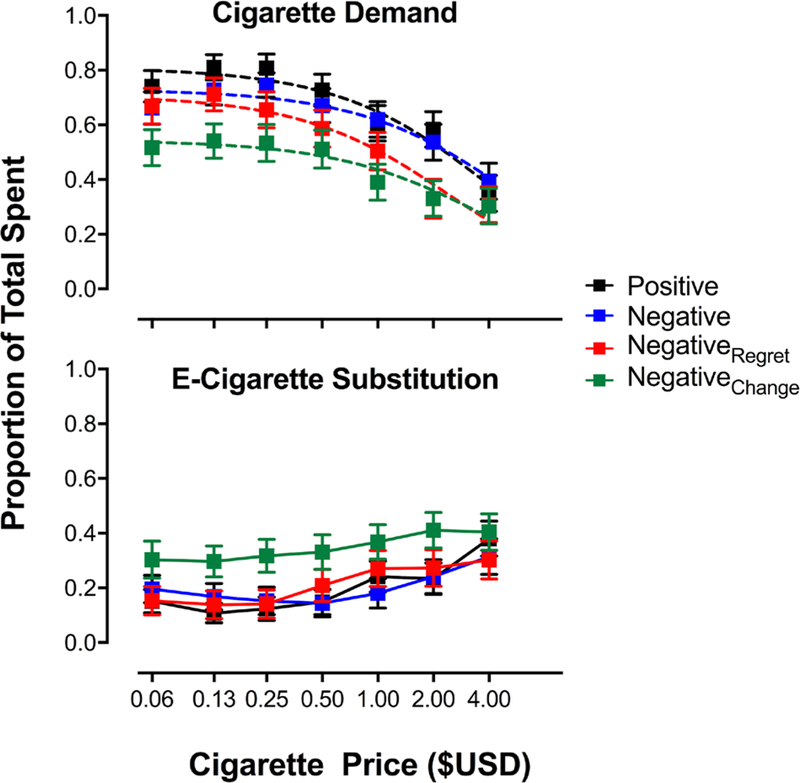

Figure 2.

ETM results for each narrative group. Dotted lines depict the Equation 1 model fit to proportion of total spent on cigarettes at each cigarette price point. x-axis is scaled in log units. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from the other narrative groups.

Public Significance.

We demonstrated that a narrative that encouraged substituting e-cigarettes for conventional cigarettes was effective at reducing conventional cigarette purchasing and increasing e-cigarette purchasing in an experimental tobacco marketplace (ETM). This finding was independent of previous participant experience with e-cigarettes. The ETM provides an effective forum for investigating the efficacy of public-health interventions, including tobacco harm-reduction, in a controlled experimental setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and by NIH Grant No. R01DA034755.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors have contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

W. K. Bickel is a principal of HealthSim, LLC and Notifius, LLC; a scientific advisory board member of Sober Grid, Inc. and DxRx, Inc.; and a consultant for ProPhase, LLC and Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc.

The authors would like to thank the Addiction Recovery Research Center and Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute faculty and staff for their continuous support.

Using Narratives to Influence Substitution of Electronic Cigarettes for Conventional Cigarettes in an online Experimental Tobacco Marketplace

Contributor Information

W. Brady DeHart, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Addiction Recovery Research Center, Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, Roanoke, VA, USA 540-526-2236

Brent A. Kaplan, Graduate Program in Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health, Addiction Recovery Research Center, Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, Roanoke, VA, USA 540-526-2072

Derek A. Pope, Department of Psychology, Addiction Recovery Research Center, Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, Roanoke, VA, USA 540-526-2017

Alexandra M. Mellis, Department of Neuroscience, Graduate Program in Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA 540-526-2237

Warren K. Bickel, Faculty of Health Sciences, Addiction Recovery Research Center, Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, Roanoke, Virginia, USA 540-526-2088

References

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, & Madden GJ (1999). Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pope DA, Kaplan BA, Brady DeHart W, Koffarnus MN, & Stein JS (2018). Electronic cigarette substitution in the experimental tobacco marketplace: A review. Preventive Medicine. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Stein JS, Moody LN, Snider SE, Mellis AM, & Quisenberry AJ (2017). Toward Narrative Theory: Interventions for Reinforcer Pathology in health behavior In Impulsivity (pp. 227–267). Springer, Cham. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey VJ (2015). gee: Generalized Estimation Equation Solver. R package version; 413–19. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gee [Google Scholar]

- CDCTobaccoFree. (2017, July 27). Tips From Former Smokers™. Retrieved September 26, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/index.html

- Centola D (2011). An experimental study of homophily in the adoption of health behavior. Science, 334(6060), 1269–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit JBF, Das E, & Vet R (2008). What works best: Objective statistics or a personal testimonial? An assessment of the persuasive effects of different types of message evidence on risk perception. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 27(1), 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard AJ, Fagerlin A, Dal Cin S, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, & Ubel PA (2010). Narratives that address affective forecasting errors reduce perceived barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Social Science & Medicine, 71(1), 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K (2012). Determinants of Tobacco Use and Renaming the FTND to the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 14(1), 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, & Voudris V (2015). Factors associated with dual use of tobacco and electronic cigarettes: A case control study. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 26(6), 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LB, Murphy ST, Chatterjee JS, Moran MB, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2015). Telling stories, saving lives: creating narrative health messages. Health Communication, 30(2), 154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel JE, DeHart WB, Madden GJ, & Odum AL (2014). Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: discounting of monetary and consumable outcomes in current and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology, 231(23), 4517–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, & Freed DE (1993). The substitutability of reinforcers. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 60(1), 141–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerström KO (1991). The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman BW, Cummings KM, Hirsch AA, Quisenberry AJ, Borland R, O’Connor RJ, Bickel WK (2017). A novel method for evaluating the acceptability of substitutes for cigarettes: The Experimental Tobacco Marketplace. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 3(3), 266–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, & van de Schoot R (2010). Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications, Second Edition Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, & 1984. (1984). Behavioral economics. Wiley Online Library; Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1901/jeab.1984.42-435/full [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR (1980). Economic concepts for the analysis of behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1901/jeab.1980.34-219/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Connor E, Babb SD, Caraballo RS, Singh T, … King BA (2015). Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2005–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(44), 1233–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, & Bickel WK (2003). The behavioral economics of cigarette smoking: The concurrent presence of a substitute and an independent reinforcer. Behavioural Pharmacology, 14(2), 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, & Bickel WK (2008). An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology, 16, 264–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BA (n.d.). beezdemand: Behavioral Economic Easy Demand. R package version; 0.0.92. Retrieved from https://github.com/brentkaplan/beezdemand [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, & Barta WD (2003). Personal Narrative as a Medium for STD/HIV Intervention: A Preliminary Study1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(11), 2327–2340. [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, & Chissom BS (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA006655

- Koffarnus MN, & Bickel WK (2014). A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(3), 222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Franck CT, Stein JS, & Bickel WK (2015). A modified exponential behavioral economic demand model to better describe consumption data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(6), 504–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, … Clark EM (2010). Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 81 Suppl, S6–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon GE (2007). Macroeconomics the Easy Way. Barron’s Educational Series. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth RV (2016). Least-Squares Means: TheRPackagelsmeans. Journal of Statistical Software, 69(1). 10.18637/jss.v069.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Borland R, Lindblom EN, Goniewicz ML, Meza R, Holford TR, … Abrams DB (2017). Potential deaths averted in USA by replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes. Tobacco Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightwood J, & Glantz SA (2016). Smoking behavior and healthcare expenditure in the United States, 1992–2009: Panel data estimates. PLoS Medicine, 13(5), e1002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE (1987). An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. Commons ML; Mazur JE; Nevin JA, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney ME, Leventhal AM, & Hatsukami DK (2006). Attitudes and knowledge about nicotine and nicotine replacement therapy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 8(3), 435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé E, Jain P, & Chung AH (2012). Reinforcement or reactance? Examining the effect of an explicit persuasive appeal following an entertainment-education narrative. The Journal of Communication, 62(6), 1010–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, Moran MB, Zhao N, Amezola de Herrera P, & Baezconde-Garbanati LA (2015). Comparing the relative efficacy of narrative vs non-narrative health messages in reducing health disparities using a randomized trial. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 2117–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LJ, Patel D, Davis K, Ridgeway W, Shafer P, & Cox S (2016). Evaluation of the National Tips From Former Smokers Campaign: the 2014 longitudinal cohort. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nummenmaa L, Saarimäki H, Glerean E, Gotsopoulos A, Jääskeläinen IP, Hari R, & Sams M (2014). Emotional speech synchronizes brains across listeners and engages large-scale dynamic brain networks. NeuroImage, 102, 498–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL (2011). Delay discounting: I’m a k, you’re a k. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 96(3), 427–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM (2001). A behavioral economic analysis of polydrug abuse in alcoholics: Asymmetrical substitution of alcohol and cocaine. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 62, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CV (2009). Debunking the claim that abstinence is usually healthier for smokers than switching to a low-risk alternative, and other observations about anti-tobacco-harm-reduction arguments. Harm Reduction Journal, 6, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polosa R, Rodu B, Caponnetto P, Maglia M, & Raciti C (2013). A fresh look at tobacco harm reduction: the case for the electronic cigarette. Harm Reduction Journal, 10, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Science. (2018). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes : Health and Medicine Division. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2018, from http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2018/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes.aspx [PubMed]

- Quisenberry AJ, Eddy CR, Patterson DL, Franck CT, & Bickel WK (2015). Regret Expression and Social Learning Increases Delay to Sexual Gratification. PloS One, 10(8), e0135977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quisenberry AJ, Koffarnus MN, Epstein LH, & Bickel WK (2017). The Experimental Tobacco Marketplace II: Substitutability and sex effects in dual electronic cigarette and conventional cigarette users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 551–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quisenberry AJ, Koffarnus MN, Hatz LE, Epstein LH, & Bickel WK (2016). The Experimental Tobacco Marketplace I: Substitutability as a function of the price of conventional cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 18(7), 1642–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Mnatzaganian G, & Worrall-Carter L (2015). E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 10(3), e0122544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians of London. Tobacco Advisory Group, & Royal College of Physicians of London (2007). Harm Reduction in Nicotine Addiction: Helping People who Can’t Quit. Royal College of Physicians of London. [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, Bickel WK, Madden GJ, & Badger GJ (1999). Comparing the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine containing and de-nicotinized cigarettes: a behavioral economic analysis. Psychopharmacology, 147(2), 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider SE, Cummings KM, & Bickel WK (2017). Behavioral economic substitution between conventional cigarettes and e-cigarettes differs as a function of the frequency of e-cigarette use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline Follow-Back. In Measuring Alcohol Consumption (pp. 41–72). Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Soneji SS, Sung H-Y, Primack BA, Pierce JP, & Sargent JD (2018). Quantifying population-level health benefits and harms of e-cigarette use in the United States. PloS One, 13(3), e0193328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Koffarnus MN, O’Connor RJ, Hatsukami DK, & Bickel WK (2017). Effects of filter ventilation on behavioral economic demand for cigarettes: A preliminary investigation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 10.1093/ntr/ntx164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AG, Franck CT, Koffarnus MN, & Bickel WK (2016). Behavioral economics of cigarette purchase tasks: Within-subject comparison of real, potentially real, and hypothetical cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 18(5), 524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbottom A, Bekker HL, Conner M, & Mooney A (2008). Does narrative information bias individual’s decision making? A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2079–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, Simpson SA, & Pechacek TF (2015). Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: an update. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(3), 326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, & Higgins ST (2008). Turning k on its head: Comments on use of an ED50 in delay discounting research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95(1–2), 169–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.