Abstract

This paper proposes an algorithm for solving structured optimization problems, which covers both the backward–backward and the Douglas–Rachford algorithms as special cases, and analyzes its convergence. The set of fixed points of the corresponding operator is characterized in several cases. Convergence criteria of the algorithm in terms of general fixed point iterations are established. When applied to nonconvex feasibility including potentially inconsistent problems, we prove local linear convergence results under mild assumptions on regularity of individual sets and of the collection of sets. In this special case, we refine known linear convergence criteria for the Douglas–Rachford (DR) algorithm. As a consequence, for feasibility problem with one of the sets being affine, we establish criteria for linear and sublinear convergence of convex combinations of the alternating projection and the DR methods. These results seem to be new. We also demonstrate the seemingly improved numerical performance of this algorithm compared to the RAAR algorithm for both consistent and inconsistent sparse feasibility problems.

Keywords: Almost averagedness, Picard iteration, Alternating projection method, Douglas–Rachford method, RAAR algorithm, Krasnoselski–Mann relaxation, Metric subregularity, Transversality, Collection of sets

Introduction

Convergence analysis has been one of the central and very active applications of variational analysis and mathematical optimization. Examples of recent contributions to the theory of the field that have initiated efficient programs of analysis are [1, 2, 7, 38]. It is the common recipe emphasized in these and many other works that there are two key ingredients required in order to derive convergence of a numerical method (1) regularity of individual functions or sets such as convexity and averaging property, and (2) regularity of collections of functions or sets at their critical points such as transversality, Kurdyka-Łojasiewicz property and metric subregularity. As a result, the question about convergence of a solving method can often be reduced to checking whether certain regularity properties of the problem data are satisfied. There have been a considerable number of papers studying these two ingredients of convergence analysis in order to establish sharper convergence criteria in various circumstances, especially those applicable to algorithms for solving nonconvex problems [5, 12, 13, 19, 26, 27, 31–33, 38, 42, 45].

This paper suggests an algorithm called , which covers both the backward-backward and the DR algorithms as special cases of choosing the parameter , and analyzes its convergence. When applied to feasibility problem for two sets one of which is affine, is a convex combination of the alternating projection and the DR methods. On the other hand, can be viewed as a relaxation of the DR algorithm. Motivation for relaxing the DR algorithm comes from the lack of stability of this algorithm when applied to inconsistent problems. This phenomenon has been observed for the Fourier phase retrieval problem which is essentially inconsistent due to the reciprocal relationship between the spatial and frequency variables of the Fourier transform [35, 36]. To address this issue, a relaxation of the DR algorithm, often known as the RAAR algorithm, was proposed and applied to phase retrieval problems by Luke in the aforementioned papers. In the framework of feasibility, the RAAR algorithm is described as a convex combination of the basic DR operator and one of the projectors. Our preliminary numerical experiments have revealed a promising performance of algorithm in comparison with the RAAR method. This observation has motivated the study of convergence analysis of algorithm in this paper.

After introducing the notation and proving preliminary results in Sect. 2, we introduce as a general fixed point operator, characterize the set of fixed points of (Proposition 1), and establish abstract convergence criteria for iterations generated by (Theorem 2) in Sect. 3. We discuss algorithm in the framework of feasibility problems in Sect. 4. The set of fixed points of is characterized for convex inconsistent feasibility (Proposition 3). For consistent feasibility we show that almost averagedness of (Proposition 4) and metric subregularity of (Lemma 3) can be obtained from regular properties of the individual sets and of the collection of sets, respectively. As a result, the two regularity notions are combined to yield local linear convergence of iterations generated by (Theorem 4). Section 5 is devoted to demonstrate the improved numerical performance of algorithm compared to the RAAR algorithm for both consistent and inconsistent feasibility problems. In this section, we study the feasibility approach for solving the sparse optimization problem. Our linear convergence result established in Sect. 4 for iterations generated by is also illustrated in this application (Theorem 5).

Notation and preliminary results

Our notation is standard, c.f. [11, 40, 46]. The setting throughout this paper is a finite dimensional Euclidean space . The norm denotes the Euclidean norm. The open unit ball in a Euclidean space is denoted , and stands for the open ball with radius and center x. The distance to a set with respect to the bivariate function is defined by

We use the convention that the distance to the empty set is . The set-valued mapping

is the projector on A. An element is called a projection. This exists for any closed set . Note that the projector is not, in general, single-valued. Closely related to the projector is the prox mapping corresponding to a function f and a stepsize [41]

When is the indicator function of A, that is if and otherwise, then for all . The inverse of the projector, , is defined by

The proximal normal cone to A at is the set, which need not be either closed or convex,

| 1 |

If , then is defined to be empty. Normal cones are central to characterizations both of the regularity of individual sets and of the regularity of collections of sets. For a refined numerical analysis of projection methods, one also defines the -proximal normal cone to A at by

When , it coincides with the proximal normal cone (1).

For and , a set A is -regular relative to at [13, Definition 2.9] if for all , and ,

When , the quantifier “relative to” is dropped.

For a set-valued operator , its fixed point set is defined by . For a number , we denote the -reflector of T by . A frequently used example in this paper corresponds to T being a projector.

In the context of convergence analysis of Picard iterations, the following generalization of the Fejér monotonicity of sequences appears frequently, see, for example, the book [4] or the paper [39] for the terminology.

Definition 1

(Linear monotonicity) The sequence is linearly monotone with respect to a set with rate if

Our analysis follows the abstract analysis program proposed in [38] which requires the two key components of the convergence: almost averagedness and metric subregularity.

Definition 2

(Almost nonexpansive/averaging mappings) [38] Let and .

-

(i)T is pointwise almost nonexpansive at y on U with violation if for all , and ,

-

(ii)T is pointwise almost averaging at y on U with violation and averaging constant if for all , and ,

2

When a property holds at all on U, we simply say that the property holds on U.

From Definition 2, almost nonexpansiveness is actually the almost averaging property with the same violation and averaging constant .

Remark 1

(the range of quantitative constants) In the context of Definition 2, it is natural to consider violation and averaging constant . Mathematically, it also makes sense to consider and provided that the required estimate (2) holds true. Simple examples for the later case are linear contraction mappings. In this paper, averaging constant will frequently be involved implicitly in intermediate steps of our analysis without any contradiction or confusion. This is the reason why in Definition 2 (ii) we considered instead of as in [38, Definition 2.2].

It is worth noting that if the iteration is linearly monotone with respect to with rate and T is almost averaging on some neighborhood of with averaging constant , then converges R-linearly to a fixed point of T [39, Proposition 3.5].

We next prove a fundamental preliminary result for our analysis regarding almost averaging mappings.

Lemma 1

Let , , , and . The following two statements are equivalent.

-

(i)

T is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant .

-

(ii)

The -reflector of T, , is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant .

Proof

Take any , , , and . We have by definition of and [4, Corollary 2.14] that

| 3 |

We also note that

| 4 |

(i) (ii). Suppose that T is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant . Substituting (2) into (3) and using (4), we obtain that

| 5 |

which means that is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant .

(ii) (i). Suppose that is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant , that is, the inequality (5) is satisfied. Substituting (3) into (5) and using (4), we obtain

Equivalently,

Hence T is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant and the proof is complete.

Lemma 1 generalizes [13, Lemma 2.4] where the result was proved for and .

The next lemma recalls facts regarding the almost averagedness of projectors and reflectors associated with regular sets.

Lemma 2

Let be closed and -regular at and define

-

(i)

The projector is pointwise almost nonexpansive on U at every point with violation .

-

(ii)

The projector is pointwise almost averaging on U at every point with violation and averaging constant 1 / 2.

-

(iii)

The -reflector is pointwise almost averaging on U at every point with violation and averaging constant .

Proof

Statements (i) and (ii) can be found in [13, Theorem 2.14] or [38, Theorem 3.1 (i) & (iii)]. Statement (iii) follows from (ii) and Lemma 1 applied to and .

The following concept of metric subregularity with functional modulus has played a central role, explicitly or implicitly, in the convergence analysis of Picard iterations [1, 13, 38, 39]. Recall that a function is a gauge function if is continuous and strictly increasing and .

Definition 3

(Metric subregularity with functional modulus) A mapping is metrically subregular with gauge on for y relative to if

When is a linear function, that is , one says “with constant ” instead of “with gauge ”. When , the quantifier “relative to” is dropped.

Metric subregularity has many important applications in variational analysis and mathematical optimization, see the monographs and papers [11, 15–18, 20, 21, 25, 40, 44]. For the discussion of metric subregularity in connection with subtransversality of collections of sets, we refer the reader to [23, 24, 29, 30].

The next theorem serves as the basic template for the quantitative convergence analysis of fixed point iterations. By the notation where is a subset of , we mean that and for all . This simplification of notation should not lead to any confusion if one keeps in mind that there may exist fixed points of T that are not in . For the importance of the use of in isolating the desirable fixed point, we refer the reader to [1, Example 1.8]. In the following, denotes the relative interior of .

Theorem 1

[38, Theorem 2.1] Let for and let be closed and nonempty such that for all . Let be a neighborhood of S such that . Suppose that

T is pointwise almost averaging at all points with violation and averaging constant on , and

- there exists a neighborhood of and a constant such that for all , and all the estimate

holds whenever .6

Then for all

whenever .

In particular, if , then for any initial point the iteration satisfies

with for all k such that for .

Remark 2

[38, p. 13] In the case of condition (6) reduces to metric subregularity of the mapping for 0 on the annular set , that is

The inequality then states that the constant of metric subregularity is sufficiently large relative to the violation of the averaging property of T to guarantee linear progression of the iterates through that annular region.

For a comprehensive discussion on the roles of S and in the analysis program of Theorem 1, we would like to refer the reader to the paper [38].

For the sake of simplification in terms of presentation, we have chosen to reduce the number of technical constants appearing in the analysis. It would be obviously analogous to formulate more theoretically general results by using more technical constants in appropriate places.

as a fixed point operator

We consider the problem of finding a fixed point of the operator

| 7 |

where and are assumed to be easily computed.

Examples of include the backward-backward and the DR algorithms [8, 10, 34, 36, 43] for solving the structured optimization problem

under different assumptions on the functions . Indeed, when are the prox mappings of with parameters , then with and 1 takes the form and , respectively.

We first characterize the set of fixed points of via those of the constituent operators .

Proposition 1

Let , and consider defined at (7). The following statements hold true.

-

(i)

.

As a consequence, -

(ii)Suppose that is the projector on an affine set A and is single-valued. Then

8

Proof

(i). We have by the construction of that

(ii). We first take an arbitrary and prove that

Indeed, from , we get

| 9 |

In particular, . Thus by equality (9) and the assumption that is affine, we have

| 10 |

Substituting (10) into (9) also yields

Finally, let us take an arbitrary x satisfying and prove that . Indeed, we note that . Since is affine, one can easily check (10) and then (9), which is equivalent to . The proof is complete.

The inclusion (8) in Proposition 1 can be strict as shown in the next example.

Example 1

Let us consider , the set and the two operators and . Then for any point with , we have but , that is .

The next proposition shows that the almost averagedness of naturally inherits from that of and via Krasnoselski–Mann relaxations.

Proposition 2

(Almost averagedness of ) Let , be almost averaging on with violation and averaging constant and define the set

Then is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant .

Proof

By the implication (i) (ii) of Lemma 1, the operators are almost averaging on with violation and averaging constant . Then thanks to [38, Proposition 2.4 (iii)], the operator is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant . Note that by Proposition 1. We have by the implication (ii) (i) of Lemma 1 that is almost averaging on U with violation and averaging constant as claimed.

We next discuss convergence of based on the abstract results established in [38]. Our agenda is to verify the assumptions of Theorem 1. To simplify the exposure in terms of presentation, we have chosen to state the results corresponding to and in Theorem 1. In the sequel, we will denote, for a nonnegative real ,

Theorem 2

(Convergence of algorithm with metric subregularity) Let be defined at (7), and . Suppose that for each , the following conditions are satisfied.

-

(i)

is almost averaging on with violation and averaging constant , and is almost averaging on the set with violation and averaging constant .

-

(ii)The mapping is metrically subregular on for 0 with gauge satisfying

where and .11

Then all iterations starting in satisfy

| 12 |

and

| 13 |

where .

In particular, if is bounded from below by some for all n sufficiently large, then the convergence (12) is R-linear with rate at most .

Proof

For each , we verify the assumptions of Theorem 1 for , and . Under assumption (i) of Theorem 2, Proposition 2 ensures that is almost averaging on with violation and averaging constant . In other words, condition (a) of Theorem 1 is satisfied with and . Assumption (ii) of Theorem 2 also fulfills condition (b) of Theorem 1 with in view of Remark 2. Theorem 1 then yields the conclusion of Theorem 2 after a straightforward care of the involving quantitative constants.

The first inequality in (11) essentially says that the gauge function can be bounded from below by a linear function on the reference interval.

Remark 3

In Theorem 2, the fundamental goal of formulating assumption (i) on the set and assumption (ii) on the set is that one can characterize sublinear convergence of an iteration on via linear progression of its iterates through each of the annular set . This idea is based on the fact that for larger n, the almost averaging property of on is always improved but the metric subregularity on may get worse, however, if the corresponding quantitative constants still satisfy condition (11), then convergence is guaranteed. For an illustrative example, we refer the reader to [38, Example 2.4].

Application to feasibility

We consider algorithm for solving feasibility problem involving two closed sets ,

| 14 |

Note that with and 1 corresponds to the alternating projections and the DR method , respectively.

It is worth recalling that feasibility problem for sets can be reformulated as a feasibility problem for two constructed sets on the product space with one of the later sets is a linear subspace, and the regularity properties in terms of both individual sets and collections of sets of the later sets are inherited from those of the former ones [3, 32].

When A is an affine set, then the projector is affine and is a convex combination of the alternating projection and the DR methods since

In this case, we establish convergence results for all convex combinations of the alternating projection and the DR methods. To our best awareness, this kind of results seems to be new.

Recall that when applied to inconsistent feasibility problems the DR operator has no fixed points. We next show that the set of fixed points of with for convex inconsistent feasibility problems is nonempty. This result follows the lines of [36, Lemma 2.1] where the fixed point set of the RAAR operator is characterized.

Proposition 3

(Fixed points of for convex inconsistent feasibility) For closed convex sets , let , , and . Then

Proof

We first show that . Pick any and denote as definitions of E and F. We are checking that

Since and , we get .

Analogously, since and

we have .

Hence,

That is .

We next show that . Pick any . Let and . Thanks to and the definition of ,

| 15 |

Now, for any , since A is closed and convex, we have

On the other hand, for any , since B is closed and convex, we have

Combining the last two inequalities yields

Take a sequence in A and a sequence in B such that . Then

| 16 |

Taking the limit and using the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality yields

Conversely, by (15) with noting that and ,

Hence , and taking the limit in (16), which yields . Since and , we have and, therefore,

We next discuss the two key ingredients for convergence of algorithm applied to feasibility problems: 1) almost averagedness of , and 2) metric subregularity of . The two properties will be deduced from the -regularity of the individual sets and the transversality of the collection of sets, respectively.

The next proposition shows averagedness of applied to feasibility problems involving -regular sets.

Proposition 4

Let A and B be -regular at and define the set

| 17 |

Then is pointwise almost averaging on U at every point with averaging constant and violation

| 18 |

Proof

Let us define the two sets

and note that if and only if and . Thanks to Lemma 2 (iii), and are pointwise almost averaging at every point with violation and averaging constant on and , respectively. Then due to [38, Proposition 2.4 (iii)], the operator is pointwise almost averaging on U at every point with averaging constant and violation , where is given by (18). Note that by Proposition 1. Thanks to Lemma 1, is pointwise almost averaging on U at every point with violation and averaging constant as claimed.

Remark 4

It follows from Lemma 2 (i) & (iii) that the set U defined by (17) contains at least the ball , where

We next integrate Proposition 4 into Theorem 2 to obtain convergence of algorithm for solving consistent feasibility problems involving -regular sets.

Corollary 1

(Convergence of algorithm for feasibility) Consider the algorithm defined at (14) and suppose that . Denote for a nonnegative real . Suppose that there are , and such that A and B are -regular at avery point , where

and for each , the mapping is metrically subregular on for 0 with gauge satisfying

where is given at (18).

Then all iterations starting in satisfy (12) and (13) with .

In particular, if is bounded from below by some for all n sufficiently large, then eventually converges R-linearly to a point in with rate at most .

Proof

Let any , for some , and . A combination of Proposition 4 and Remark 4 implies that is pointwise almost averaging on at every point with violation given by (18) and averaging constant . In other words, condition (a) of Theorem 1 is satisfied. Condition (b) of Theorem 1 is also fulfilled by the same argument as the one used in Theorem 2. The desired conclusion now follows from Theorem 1.

In practice, the metric subregularity assumption is often more challenging to be verified than the averaging property. In the concrete example of consistent alternating projections , that metric subregularity condition holds true if and only if the collection of sets is subtransversal. We next show that the metric subregularity of can be deduced from the transversality of the collection of sets . As a result, if the sets are also sufficiently regular, then local linear convergence of the iteration is guaranteed.

We first describe the concept of relative transversality of collections of sets. In the sequel, we set , the smallest affine set in containing both A and B.

Assumption 3

The collection is transversal at relative to with constant , that is, for any , there exists such that

holds for all , , and .

Thanks to [22, Theorem 1] and [28, Theorem 1], Assumption 3 also ensures subtransversality of at relative to with constant at least on the neighborhood , that is

| 19 |

The next lemma is at the heart of our subsequent discussion.

Lemma 3

Suppose that Assumption 3 is satisfied. Then for any , there exists a number such that for all and ,

| 20 |

where is defined by

| 21 |

Proof

For any , there is a number satisfying the property described in Assumption 3. Let us set and show that condition (20) is fulfilled with .

Indeed, let us consider any , , , and . From the choice of , it is clear that . Since and , Assumption 3 yields that

| 22 |

By the definition of , we have

| 23 |

where the first inequality follows from (22).

We will take care of the two possible cases regarding as follows.

Case 1 . Thanks to (23) we get

| 24 |

Case 2 . By the triangle inequality and the construction of , we get

| 25 |

Since

we always have from (24) and (25) that

| 26 |

Combining (23), (26) and (19), we obtain

which yields (20) as claimed.

In the special case that , Lemma 3 refines [13, Lemma 3.14] and [45, Lemma 4.2] where the result was proved for the DR operator with an additional assumption on regularity of the sets.

The next result is the final preparation for our linear convergence result.

Lemma 4

[45, Proposition 2.11] Let , be closed and . Suppose that there are and such that for all , and ,

| 27 |

Then every iteration starting sufficiently close to converges R-linearly to a point . In particular,

We are now ready to prove local linear convergence for algorithm which generalizes the corresponding results established in [13, 45] for the DR method.

Theorem 4

(Linear convergence of algorithm for feasibility) In addition to Assumption 3, suppose that A and B are -regular at with , where and are given by (18) and (21), respectively. Then every iteration starting sufficiently close to converges R-linearly to a point in .

Proof

Assumption 3 ensures the existence of such that Lemma 3 holds true. In view of Proposition 4 and Remark 4, one can find a number such that is pointwise almost averaging on at every point with violation given by (18) and averaging constant . Define .

Now let us consider any , and . It is clear that . Proposition 4 and Lemma 3 then respectively yield

| 28 |

| 29 |

where is given by (21).

Substituting (29) into (28), we get

which yields condition (27) of Lemma 4 and the desired conclusion now follows from this lemma.

Application to sparse optimization

Our goal in this section is twofold: 1) to illustrate the linear convergence of algorithm formulated in Theorem 4 via the sparse optimization problem, and 2) to demonstrate a promising performance of the algorithm in comparison with the RAAR algorithm for this applied problem.

Sparse optimization

We consider the sparse optimization problem

| 30 |

where is a full rank matrix, b is a given vector in , and is the number of nonzero entries of the vector x. The sparse optimization problem with complex variable is defined analogously by replacing by everywhere in the above model.

Many strategies for solving (30) have been proposed. We refer the reader to the famous paper by Candès and Tao [9] for solving this problem by using convex relaxations. On the other hand, assuming to have a good guess on the sparsity of the solutions to (30), one can tackle this problem by solving the sparse feasibility problem [14] of finding

| 31 |

where and .

It is worth mentioning that the initial guess s of the true sparsity is not numerically sensitive with respect to various projection methods, that is, for a relatively wide range of values of s above the true sparsity, projection algorithms perform very much in the same nature. Note also that the approach via sparse feasibility does not require convex relaxations of (30) and thus can avoid the likely expensive increase of dimensionality.

We run the two algorithms and RAAR to solve (31) and compare their numerical performances. By taking s smaller than the true sparsity, we can also compare their performances for inconsistent feasibility.

Since B is affine, there is the closed algebraic form for the projector ,

where is the Moore–Penrose inverse of M. We have denoted the transpose matrix of M and taken into account that M is full rank. There is also a closed form for [6]. For each , let us denote the set of all s-tubles of indices of s largest in absolute value entries of x. The set can contain multiple such s-tubles. The projector can be described as

For convenience, we recall the two algorithms in this specific setting

Convergence analysis

We analyze the convergence of algorithm for the sparse feasibility problem (31). The next theorem establishes local linear convergence of algorithm for solving sparse feasibility problems.

Theorem 5

(Linear convergence of algorithm for sparse feasibility) Let and suppose that s is the sparsity of the solutions to the problem (30). Then any iteration starting sufficiently close to converges R-linearly to .

Proof

We first show that is an isolated point of . Since s is the sparsity of the solutions to (30), we have that and the set contains a unique element, denoted . Note that is the unique s-dimensional space component of containing , where is the canonical basic of . Let us denote

We claim that

| 32 |

| 33 |

Indeed, for any , we have by definition of that for all . Hence and . This proves (32).

For (33), it suffices to show the singleton of since we already know that . Suppose otherwise that there exists with for some index j. Since both and B are affine, the intersection contains the line passing x and . In particular, it contains the point . Then we have that and as . This contradicts to the assumption that s is the sparsity of the solutions to (30), and hence (33) is proved.

A combination of (32) and (33) then yields

| 34 |

This means that is an isolated point of as claimed. Moreover, the equalities in (34) imply that

Therefore, for any starting point , the iteration for solving (31) is identical to that for solving the feasibility problem for the two sets and B. Since and B are two affine subspaces intersecting at the unique point by (33), the collection of sets is transversal at relative to the affine hull . Theorem 4 now can be applied to conclude that the iteration converges R-linearly to . The proof is complete.

It is worth mentioning that the convergence analysis in Theorem 5 is also valid for the RAAR algorithm.

Numerical experiment

We now set up a toy example as in [9, 14] which involves an unknown true object with (the sparsity rate is .005). Let b be 1 / 8 of the measurements of , the Fourier transform of , with the sample indices denoted . The Poisson noise was added when calculating the measurement b. Note that since is real, is conjugate symmetric, we indeed have nearly a double number of measurements. In this setting, we have

and the two prox operators, respectively, take the forms

where denotes the real part of the complex number x(k), and is the inverse Fourier transform.

The initial point was chosen randomly, and a warm-up procedure with 10 DR iterates was performed before running the two algorithms. The stopping criterion was used. We have used the Matlab ProxToolbox [37] to run this numerical experiment. The parameters were chosen in such a way that the performance is seemingly optimal for both algorithms. We chose for the RAAR algorithm and for algorithm in the case of consistent feasibility problem corresponding to , and for the RAAR algorithm and for algorithm in the case of inconsistent feasibility problem corresponding to .

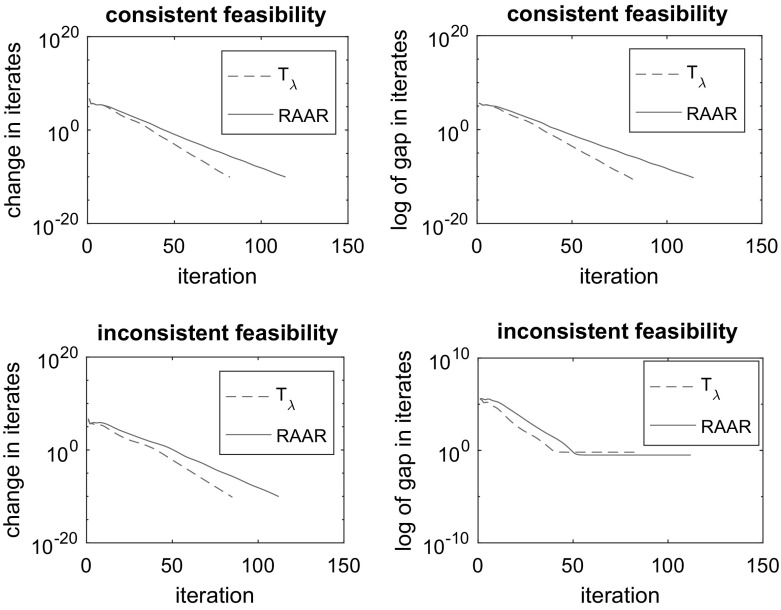

The change of distances between two consecutive iterates is of interest. When linear convergence appears to be the case, it can yield useful information of the convergence rate. Under the assumption that the iterates will remain in the convergence area, one can obtain error bounds for the distance from the current iterate to a nearest solution. We also pay attention to the gaps in iterates that in a sense measure the infeasibility at the iterates. If we think feasibility problem as the problem of minimizing the sum of the squares of the distance functions to the sets, then gaps in iterates are the values of that function evaluated at the iterates. For the two algorithms under consideration, the iterates are themselves not informative but their shadows, by which we mean the projections of the iterates on one of the sets. Hence, the gaps in iterates are calculated for the iterate shadows instead of the iterates themselves.

Figure 1 summarizes the performances of the two algorithms for both consistent and inconsistent sparse feasibility problems. We first emphasize that the algorithms appear to be convergent in both cases of feasibility. For the consistent case, algorithm appears to perform better than the RAAR algorithm in terms of both the iterate changes and gaps. Also, the CPU time of algorithm is around less than that of the RAAR algorithm. For the inconsistent case, we have a similar observation except that the iterate gaps for the RAAR algorithm are slightly better (smaller) than those for algorithm . Extensive numerical experiments in imaging problems illustrating the empirical performance of algorithm will be the future work.

Fig. 1.

Performances of the RAAR and algorithms for sparse feasibility problem: iterate changes in consistent case (top-left), iterate gaps in consistent case (top-right), iterate changes in inconsistent case (bottom-left) and iterate gaps in inconsistent case (bottom-right)

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Dr. Russell Luke and Prof. Dr. Alexander Kruger for their encouragement and valuable suggestions during the preparation of this work. He also would like to thank the anonymous referees for their very helpful and constructive comments on the manuscript version of the paper.

Footnotes

The research leading to these results has received funding from the German-Israeli Foundation Grant G-1253-304.6 and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement No. 339681.

References

- 1.Aspelmeier T, Charitha C, Luke DR. Local linear convergence of the ADMM/Douglas–Rachford algorithms without strong convexity and application to statistical imaging. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2016;9(2):842–868. doi: 10.1137/15M103580X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attouch H, Bolte J, Redont P, Soubeyran A. Proximal alternating minimization and projection methods for nonconvex problems: an approach based on the Kurdyka–Łojasiewicz inequality. Math. Oper. Res. 2010;35(2):438–457. doi: 10.1287/moor.1100.0449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauschke HH, Borwein JM. On projection algorithms for solving convex feasibility problems. SIAM Rev. 1996;38(3):367–426. doi: 10.1137/S0036144593251710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauschke HH, Combettes PL. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauschke HH, Luke DR, Phan HM, Wang X. Restricted normal cones and the method of alternating projections: applications. Set-Valued Var. Anal. 2013;21:475–501. doi: 10.1007/s11228-013-0238-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauschke HH, Luke DR, Phan HM, Wang X. Restricted normal cones and sparsity optimization with affine constraints. Found. Comput. Math. 2014;14:63–83. doi: 10.1007/s10208-013-9161-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolte J, Sabach S, Teboulle M. Proximal alternating linearized minimization for nonconvex and nonsmooth problems. Math. Program. 2014;146(1–2):459–494. doi: 10.1007/s10107-013-0701-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borwein JM, Tam MK. The cyclic Douglas–Rachford method for inconsistent feasibility problems. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2015;16(4):537–584. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candés E, Tao T. Decoding by linear programming. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 2005;51(12):4203–4215. doi: 10.1109/TIT.2005.858979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combettes, P.L., Pesquet, J.-C.: Proximal splitting methods in signal processing. In: Fixed-Point Algorithms for Inverse Problems in Science and Engineering, vol. 49. Springer, Berlin, pp. 185–212 (2011)

- 11.Dontchev AL, Rockafellar RT. Implicit Functions and Solution Mapppings. New York: Srpinger; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drusvyatskiy D, Ioffe AD, Lewis AS. Transversality and alternating projections for nonconvex sets. Found. Comput. Math. 2015;15(6):1637–1651. doi: 10.1007/s10208-015-9279-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hesse R, Luke DR. Nonconvex notions of regularity and convergence of fundamental algorithms for feasibility problems. SIAM J. Optim. 2013;23(4):2397–2419. doi: 10.1137/120902653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesse R, Luke DR, Neumann P. Alternating projections and Douglas–Rachford for sparse affine feasibility. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 2014;62(18):4868–4881. doi: 10.1109/TSP.2014.2339801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ioffe AD. Metric regularity and subdifferential calculus. Russian Math. Surv. 2000;55(3):501–558. doi: 10.1070/RM2000v055n03ABEH000292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ioffe AD. Regularity on a fixed set. SIAM J. Optim. 2011;21(4):1345–1370. doi: 10.1137/110820981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ioffe AD. Nonlinear regularity models. Math. Program. 2013;139(1–2):223–242. doi: 10.1007/s10107-013-0670-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ioffe AD. Metric regularity: a survey. Part I. Theory. J. Aust. Math. Soc. 2016;101(2):188–243. doi: 10.1017/S1446788715000701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanh Phan Q, Kruger AY, Thao Nguyen H. An induction theorem and nonlinear regularity models. SIAM J. Optim. 2015;25(4):2561–2588. doi: 10.1137/140991157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klatte D, Kummer B. Nonsmooth Equations in Optimization. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klatte D, Kummer B. Optimization methods and stability of inclusions in Banach spaces. Math. Program. 2009;117(1–2):305–330. doi: 10.1007/s10107-007-0174-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruger AY. Stationarity and regularity of set systems. Pac. J. Optim. 2005;1(1):101–126. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruger AY. About regularity of collections of sets. Set-Valued Anal. 2006;14:187–206. doi: 10.1007/s11228-006-0014-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruger AY. About stationarity and regularity in variational analysis. Taiwan. J. Math. 2009;13(6A):1737–1785. doi: 10.11650/twjm/1500405612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruger AY. Error bounds and metric subregularity. Optimization. 2015;64(1):49–79. doi: 10.1080/02331934.2014.938074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruger, A.Y., Luke, D.R., Thao, Nguyen H.: Set regularities and feasibility problems. Math. Program. B. 10.1007/s10107-016-1039-x

- 27.Kruger AY, Luke DR, Thao Nguyen H. About subtransversality of collections of sets. Set-Valued Var. Anal. 2017;25(4):701–729. doi: 10.1007/s11228-017-0436-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruger AY, Thao Nguyen H. About uniform regularity of collections of sets. Serdica Math. J. 2013;39:287–312. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruger AY, Thao Nguyen H. About -regularity properties of collections of sets. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2014;416(2):471–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2014.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruger AY, Thao Nguyen H. Quantitative characterizations of regularity properties of collections of sets. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2015;164:41–67. doi: 10.1007/s10957-014-0556-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruger AY, Thao Nguyen H. Regularity of collections of sets and convergence of inexact alternating projections. J. Convex Anal. 2016;23(3):823–847. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis AS, Luke DR, Malick J. Local linear convergence of alternating and averaged projections. Found. Comput. Math. 2009;9(4):485–513. doi: 10.1007/s10208-008-9036-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis AS, Malick J. Alternating projections on manifolds. Math. Oper. Res. 2008;33:216–234. doi: 10.1287/moor.1070.0291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li G, Pong TK. Douglas–Rachford splitting for nonconvex feasibility problems. Math. Program. 2016;159(1):371–401. doi: 10.1007/s10107-015-0963-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luke DR. Relaxed averaged alternating reflections for diffraction imaging. Inverse Problems. 2005;21:37–50. doi: 10.1088/0266-5611/21/1/004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luke DR. Finding best approximation pairs relative to a convex and a prox-regular set in Hilbert space. SIAM J. Optim. 2008;19(2):714–739. doi: 10.1137/070681399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luke, D.R.: ProxToolbox. http://num.math.uni-goettingen.de/proxtoolbox (2017). Accessed Aug 2017

- 38.Luke, D.R., Thao, Nguyen H., Tam, M.K.: Quantitative convergence analysis of iterated expansive, set-valued mappings. Math. Oper. Res. 10.1287/moor.2017.0898

- 39.Luke, D.R., Thao, Nguyen H., Teboulle, M.: Necessary conditions for linear convergence of Picard iterations and application to alternating projections. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1704.08926.pdf (2017)

- 40.Mordukhovich BS. Variational Analysis and Generalized Differentiation. I: Basic Theory. Berlin: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moreau J-J. Fonctions convexes duales et points proximaux dans un espace Hilbertien. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris. 1962;255:2897–2899. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noll D, Rondepierre A. On local convergence of the method of alternating projections. Found. Comput. Math. 2016;16(2):425–455. doi: 10.1007/s10208-015-9253-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patrinos, P., Stella, L., Bemporad, A.: Douglas-Rachford splitting: Complexity estimates and accelerated variants. In: 53rd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, pp. 4234–4239 (2014)

- 44.Penot J-P. Calculus Without Derivatives. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phan HM. Linear convergence of the Douglas–Rachford method for two closed sets. Optimization. 2016;65:369–385. doi: 10.1080/02331934.2015.1051532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rockafellar, R.T., Wets, R.J.-B.: Variational Analysis. Grundlehren Math. Wiss. Springer, Berlin (1998)