Abstract

Background:

Cutaneous adverse events are common with programmed death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors. However, the nature of the specific cutaneous adverse event of dermatitis has not been investigated across various PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Oncologic outcomes potentially associated with dermatitis are not well characterized.

Objective:

To assess the nature of dermatitis after exposure to a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor and oncologic outcomes associated with dermatitis.

Methods:

Retrospective, matched, case-control study conducted at a single academic center.

Results:

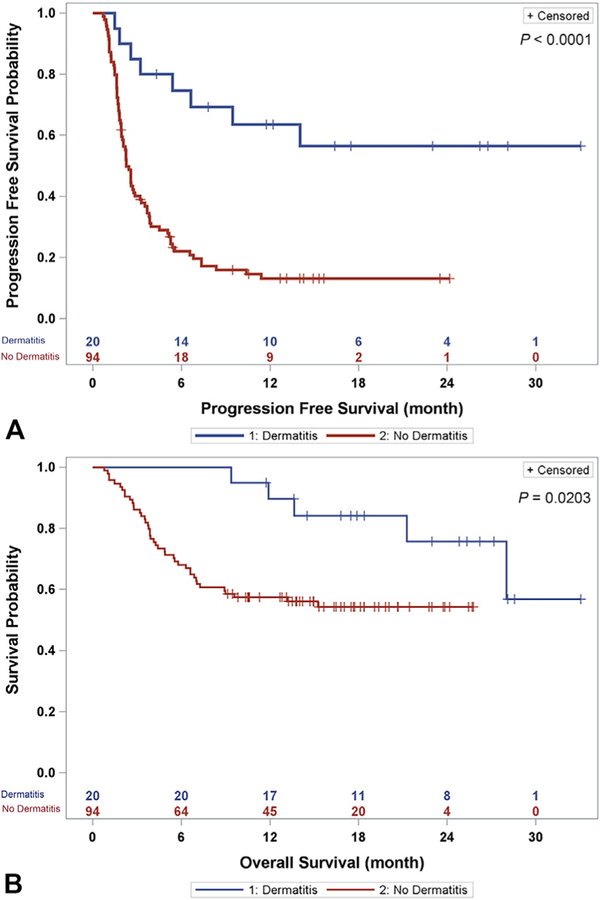

The most common histologic patterns were lichenoid dermatitis (50%) and spongiotic dermatitis (40%). The overall tumor response rate was 65.0% for the case patients and 17.0% for the controls (P = .0007) (odds ratio, 7.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.3–23.1). The progression-free survival and overall survival times were significantly longer for the case patients than for the controls by Kaplan-Meier analysis (P <.0001 and .0203, respectively).

Limitations:

The retrospective design and relatively small sample size precluded matching for all cancer types.

Conclusions:

Lichenoid and spongiotic dermatitis associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors could be a sign of robust immune response and improved oncologic outcomes. The value of PD-1/PD-L1erelated dermatitis in predicting cancer outcomes awaits investigation through prospective multicenter studies for specific cancer types. ( J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;79:1047–52.)

Keywords: checkpoint inhibitor, dermatitis, immunotherapy, inhibitor, lichenoid, nonmelanoma skin cancer, PD-1, PD-L1, programmed death 1, programmed death ligand 1, reaction pattern, spongiotic

Programmed death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors are potent immunotherapies that were recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and have been used to successfully treat multiple solid tumor types.1,2 Numerous tumor types express PD-L1, which binds to the PD-1 receptor on T cells, thereby reducing the anttumor response.3–7 Drugs of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor class can disrupt the reduced antitumor response, thereby activating the immune system against solid tumors.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are FDA approved for multiple tumor types, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, non‒small cell lung cancers, urothelial carcinomas, classic Hodgkin’s lymphomas, renal cell carcinoma, and gastrointestinal cancers. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) are common and have included rash (which will be referred to as dermatitis in this study), pruritus, and vitiligo.8,9 In one particular PD-1 inhibitor, namely, pembrolizumab, these AEs are as a whole associated with oncologic response.8,9 Nevertheless, the nature of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor‒associated dermatitis specifically and its potential short- and long-term clinical significance are not well characterized.

In this study, we have examined the types of dermatitis observed after PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor treatment and assessed multiple oncologic outcomes in a retrospective case-control study design at a single academic institution. Because of the common pathway that PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors target and their broadly similar response and AE profiles,10,11 we have examined the role of these inhibitors as a group.

Although the PD-1 inhibitors are biosimilar drugs, the exact doses can vary slightly between PD-1 inhibitors and for different tumor types, ranging from a fixed dose to weight-based dosing. For instance, nivolumab intravenous infusion can be given as a flat dose (240 mg) or a weight-based dose (3 mg/kg body weight) every 2 weeks; similarly, pembrolizumab can be administered as a flat dose (200 mg intravenously) or by weight (2 mg/kg body weight) every 3 weeks.12–14

Because PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors work by reducing the attenuation of antitumor T-cell response, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this increased immune activation may be evident in the skin as dermatitis. Hence, dermatitis could be a sign of more robust immune antitumor response. In a case series, the nature of inflammatory infiltrates in PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor‒related dermatitis has been reported in 3 patients as a lichenoid reaction pattern containing abundant T cells.8,15 Therefore, this study focuses on dermatitis as the primary AE evaluated, as compared with eruptive neoplasms16 or pruritus, because dermatitis can contain immune infiltrates with T cells, including subsets known to be important in antitumor response in nonebasal cell carcinoma solid tumors (eg, CD8+ T cells).15 Antitumor response may ultimately lead to improvements in meaningful clinical outcomes such as progression-free survival (PFS) and/or overall survival (OS).

METHODS

Following approval by the Stanford Human Subjects Panel, we queried the Stanford Cancer Research Database (covering the period from August 1, 2013, to August 2, 2016) for adult patients who had received at least 2 doses of the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab or nivolumab or the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab. Manual chart review was performed to include only patients with at least 1 summary of a subsequent treatment response that was documented at a clinic visit and consistent with written imaging reports from board-certified diagnostic radiologists. The case patients were patients who experienced a dermatitis after initiation of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor and up to 3 months after the last dose of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor and who underwent a biopsy for the dermatitis. Excluded patients were (1) those with a post‒PD-1/PD-L1 cutaneous AE of vitiligo or pruritus without dermatitis, (2) those with worsening of pre-existing dermatitis (such as psoriasis) after initiation of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor, (3) those with dermatitis attributed to another cause (such as contact dermatitis or a drug other than a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor), and (4) those who experienced onset of dermatitis after initiation of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor but did not undergo biopsy. All skin biopsy samples were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin staining, with the results documented in written reports by 1 board-certified dermatopathologist. Consensus conference with 3 board-certified dermatopathologists was utilized when there was a question about the diagnosis. This mechanism was used with 3 of the 20 case patients.

Lichenoid dermatitis was defined as a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with epidermal necrosis. Spongiotic dermatitis was defined as epidermal spongiosis with lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the vessels of the superficial plexus with the presence of eosinophils. The controls were patients with no mention of dermatitis in their progress notes after initiation of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor.

The method of propensity score matching was used to match each case patient with up to 5 controls on the basis of age, sex, number of treatment cycles at the time of dermatitis biopsy (if a case patient), and number of treatment cycles at the last documented clinic visit (if a control patient).

The treatment outcomes examined included best overall response (BOR) (as assessed by written progress notes of the treating physician), PFS, and OS. The BOR was determined by manual examination of the medical record, with best response to a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor documented by the treating physician as complete response, partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease. Disease progression included written documentation of (1) death, (2) growth of existing lesion(s), and/or (3) appearance of new cancerous lesion(s) defined as a new lesion attributed to the initial oncologic diagnosis by the treating physician. Overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the fraction of patients who had either complete response or partial response as their BOR to the treatment.

PFS was defined as the interval from time of PD-1/PD-L1 initiation to either (1) disease progression documented by the treating physician or (2) death, with censoring occurring at start of a systemic treatment for the primary tumor that was not a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor, last clinic visit date before missing progress notes documenting treatment response, or discontinuation of PD-1/PD-L1 on account of an AE. OS was defined as the interval between the time of PD-1/PD-L1 initiation to death from any cause documented in the medical record, with censoring at the last documented clinical visit or telephone interaction.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate PFS and OS, and the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to compare the case and control groups.

All tests were 2 sided, and P values less than .05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of 486 patients identified by keyword search, 20 case patients (with biopsy-proven dermatitis) met the eligibility criteria for the study after manual chart review. None of the included subjects had a history of dermatitis recorded in the medical record. Propensity matching on the basis of age, sex, and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor cycles led to selection of 94 controls (a control being a patient with no dermatitis), which was again confirmed by manual chart review. Demographic and clinical information of the patients is shown in Table I. Many more patients had received pembrolizumab (n = 49) or nivolumab (n = 60) than received atezolizumab (n = 5). Because of sample size limitation, the case patients and controls were not matched for type of cancers treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (Table II) or for the type of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor drug utilized (Table I).

Table I.

Summary of patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes

| Characteristic | All patients (N = 114) | Dermatitis (n = 20) | No dermatitis (n = 94) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at initiation of therapy, y (standard deviation) | 65.9 (12.4) | 69.9 (12.9) | 65.1 (12.2) | .12 |

| Male patients, n (%) | 62 (54.4) | 11 (55.0) | 51 (54.3) | .95 |

| Median cycles of PD-1/PD-L1 used, n (range) | 8 (2–68) | 7 (2–34) | 8 (2–68) | .53 |

| Drug used by the individual study patients, n (%) | .0002 | |||

| Nivolumab | 60 (52.6) | 3 (15.0) | 57 (60.6) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 49 (43.0) | 17 (85.0) | 32 (34.0) | |

| Atezolizumab | 5 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.3) | |

| Best overall response, number of patients (%) | ||||

| Response | <.0001 | |||

| Complete | 12 (10.5) | 7 (35.0) | 5 (5.3) | |

| Partial | 17 (14.9) | 6 (30.0) | 11 (11.7) | |

| No response | ||||

| Stable | 14 (12.3) | 3 (15.0) | 11 (11.7) | |

| Progressive | 71 (62.3) | 4 (20.0) | 67 (71.3) |

Dermatitis indicates case patients, and No dermatitis indicates controls. Significant P values are in boldface.

PD-1, Programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

Table II.

Rate of dermatitis after a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor across tumor types treated

| Tumor type treated, with subtypes as indicated | Study patients, n (%) | Patients with dermatitis, n | % of patients with dermatitis within each tumor type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 32 (28) | 1 | 3% |

| Non‒small cell | 30 (26) | 1 | 3% |

| Small cell | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Pleura | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Cutaneous | 28 (25) | 12 | 43% |

| Melanoma | 18 (16) | 7 | 25% |

| Cutaneous squamous cell | 6 (5) | 3 | 11% |

| Basal cell | 3 (3) | 1 | 4% |

| Sézary syndrome | 1 (1) | 1 | 4% |

| Head and neck | 20 (18) | 4 | 20% |

| Maxilla | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Thyroid | 1 (1) | 1 | 5% |

| Oropharynx | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Oral cavity | 6 (5) | 2 | 10% |

| Salivary gland | 5 (4) | 0 | 0% |

| Nasopharynx | 3 (3) | 0 | 0% |

| Larynx | 3 (3) | 1 | 5% |

| Gastrointestinal | 15 (13) | 0 | 0% |

| Bile duct | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Small intestine | 4 (4) | 0 | 0% |

| Colorectum | 5 (4) | 0 | 0% |

| Liver | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Genitourinary | 14 (12) | 2 | 14% |

| Bladder | 4 (4) | 0 | 0% |

| Kidney | 11 (10) | 2 | 14% |

| Urothelium | 3 (3) | 0 | 0% |

| Reproductive | 4 (4) | 1 | 25% |

| Breast | 3 (3) | 1 | 25% |

| Prostate | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Hematopoietic | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Hodgkin’s | 1 (1) | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 114 | 20 |

Cutaneous tumors were associated with a higher percentage of dermatitis after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment (boldface entries) than either head and neck or lung cancers were. The distribution of primary tumor types treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in all patients in the study (N = 114) is shown in column 2.

PD-1, Programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1.

Many more patients had received pembrolizumab (n = 49) or nivolumab (n = 60) than received atezolizumab (n = 5), with no cases of dermatitis in patients exposed to atezolizumab. There were more cases of dermatitis among those patients who had received pembrolizumab (35% [17 of 49]) than had received nivolumab (5% [3 of 60]).

Of the 20 case patients with biopsy-proven PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitoreassociated dermatitis, 50% had lichenoid dermatitis (n = 10), 40% had spongiotic dermatitis (n = 8), 5% had a lymphoid infiltrate (n = 1), and 5% had a vacuolar interface dermatitis (n = 1). There were no case patients with bullous dermatitis.

The BORs were significantly improved in PD-1/PD-L1etreated patients with dermatitis versus in those without dermatitis (P <.0001) (Table I).

Notably, the ORR of the treated cancer was significantly different with adjustment for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor used (65.0% for the case patients vs 17.0% for the controls) (P = .0007; odds ratio, 7.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3–23.1).

The specific PD-1 inhibitor used (nivolumab vs pembrolizumab) was not associated with BOR to therapy (P = .5292).

The PFS and OS times were significantly longer for the case patients than for the controls according to Kaplan-Meier analysis (P <.0001 and .0203, respectively [Fig 1]). At 1 year, the OS rates were 90% for the case patients and 57% for the controls.

Fig 1.

Oncologic outcomes of patients with and without programmed death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitoreassociated dermatitis. A, Kaplan-Meier curves show progression-free survival after initiation of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment. Patients who developed a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor‒associated dermatitis (cases patients [blue]) had significantly longer progression-free survival than did patients with no PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor‒associated dermatitis (controls [red]) (P <.0001). B, Kaplan-Meier curves show overall survival after initiation of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment. Patients who developed a PD-1/PDL1 inhibitor‒associated dermatitis (case patients [blue]) had significantly longer overall survival than did patients with no PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor‒associated dermatitis (controls [red]) (P = .0203).

Subset analysis of the case patients with lichenoid versus those with spongiotic dermatitis with regard to the aforementioned clinical outcomes showed no significant results for BOR, ORR, PFS, or OS.

Regarding management of the dermatitis, 15% of the case patients (3 of 20) required drug interruption, with 10% of them (2 of 20) undergoing permanent discontinuation of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor. Of the 2 case patients requiring permanent discontinuation, 1 received systemic steroids to treat the dermatitis and the other used topical steroids. One patient resumed PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor treatment after a pause and was managed with administration of topical steroids alone.

The most common intervention to treat the dermatitis was topical steroids (in 75% of case patients [15 of 20]). Systemic steroids were required for 10% of the case patients (2 of 20). No other types of treatment were used to treat the dermatitis. There were no cases of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor‒related dose reduction for dermatitis.

Of the 3 most common malignancies treated with PD-1/PD-L1 in this study, cutaneous malignancies (including melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and Sézary syndrome) were associated with a higher incidence of dermatitis (43% [occurring in 12 of 28 patients]) than were lung cancer (3% [occurring in 1 of 32 patients]) or head and neck cancers (20% [occurring in 4 of 20 patients]) (Table II). Notably, the rate of dermatitis differed significantly between patients with cutaneous malignancies and those with lung malignancies (P = .0003) (odds ratio, 23.25; 95% CI, 2.77–195.13), but it did not differ significantly between patients with cutaneous malignancies and those with head and neck malignancies (P = .1275). Patients with cutaneous malignancies were 23.25 times more likely (95% CI, 2.77–195.13) to develop dermatitis than were patients with lung cancers and 7.3 times more likely (95% CI, 2.6–20.8) to develop dermatitis than were patients with any noncutaneous malignancy.

DISCUSSION

Although previous reports have demonstrated lichenoid and other types of histologic patterns as being associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition,17–19 our study links the lichenoid and spongiotic types with multiple favorable oncologic outcomes, including favorable ORR, PFS, and OS. This information is useful when dermatologists counsel patients with this drug-related dermatitis. Future prospective studies could confirm the predictive value of biopsy-proven lichenoid or spongiotic dermatitis as evidence of a robust immune response leading to improved clinical outcomes.

Notably, about 10-fold more patients had received pembrolizumab or nivolumab in this study than received atezolizumab. This pattern is likely due in part to earlier FDA approval for pembrolizumab and nivolumab (in 2014 for both) than for atezolizumab (in 2016). Regarding the fact that none of the patients treated with atezolizumab had biopsy-proven dermatitis, it is possible that patients receiving atezolizumab were examined less often by a dermatologist, thereby reducing detection of dermatitis and performance of skin biopsies, as atezolizumab is not approved for a cutaneous malignancy (whereas pembrolizumab and nivolumab are approved for melanoma). Another reason for the lack of dermatitis in the patients who received atezolizumab could be the nature of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors themselves, as the rates of rash published in the package inserts indicated slightly higher rates in those taking pembrolizumab (25%) and nivolumab (21%) than in those taking atezolizumab (15%).

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and therefore its dependence on the accuracy and completeness of the medical record. Future prospective studies in which all patients with PD-1/PD-L1–associated dermatitis are given the choice to undergo skin biopsies may reduce potential dermatology referral bias. In addition, larger studies would allow clinical outcomes to be examined within each cancer type, as different cancers may have varying clinical courses, such as OS rates over time. Larger studies could also match by PD-1/PD-L1 drug. Finally, future studies may identify specific cell lineages, T-cell subtypes, and/or molecular markers within the immune infiltrates of the dermatitis that can predict favorable response, PFS, and OS.

CAPSULE SUMMARY.

Cutaneous adverse effects after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are common, but the nature and oncologic significance of dermatitis specifically is unclear.

Our data show that lichenoid and spongiotic dermatitis are the most common types of rash after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Dermatitis is significantly associated with a more favorable response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the help of Douglas Wood, MS, and Solomon Henry, MS, at the Stanford Cancer Institute Research Database for assistance in accessing this resource.

Funding sources: Mr Lee was supported by the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program. The Stanford Cancer Institute Research Database is supported by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant (5P30CA124435) and a Stanford National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources Clinical and Translational Science award (UL1 RR025744).

Abbreviations used:

- AE

adverse event

- BOR

best overall response

- CI

confidence interval

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- ORR

overall response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PD-1

programmed death 1 protein

- PD-L1

programmed death ligand 1 protein

- PFS

progression-free survival

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr Chang is a clinical investigator for Merck and Regeneron unrelated to the current study. Mr Lee, Ms Li, Mr Tran, Dr Zhu, Dr Kim, and Dr Kwong have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presented as a poster at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, February 16–20, 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369(2):134–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilie M, Hofman P. Atezolizumab in advanced non-small lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2017;9(10):3603–3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghebeh H, Mohammed S, Al-Omair A, et al. The B7-H1 (PD-L1) T lymphocyte inhibitory molecule is expressed in breast cancer patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma: correlation with important high-risk prognostic factors. Neoplasia 2006;8: 190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, et al. Programmed cell death1ligand1and tumor infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:3360–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C, Zhu Y, Jiang J, Zhao J, Zhang XG, Xu N. Immunohistochemical localization of programmed death-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) in gastric carcinoma and its clinical significance. Acta Histochem 2006;108:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Frigola X, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) expression by urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and BCG-induced granulomata: associations with localized stage progression. Cancer 2007;109:1499–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanishi J, Wada Y, Matsumoto K, Azuma M, Kikuchi K, Ueda S. Overexpression of B7-H1 (PD-L1) significantly associates with tumor grade and postoperative prognosis in human urothelial cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007; 56:1173–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanlorenzo MI, Daud A, Algazi A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151(11): 1206–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152(1): 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366(26):2443–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reck M, Delvys RA, Robinson A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keytruda (pembrolizumab) [package insert] Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opdivo (nivolumab) [package insert] Lawrenceville, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tecentriq (atezolizumab) [package insert] South San Francisco, CA: Genetech, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaberg KB, Novoa R, Wakelee HA, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of lichenoid reactions in patients treated with anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 therapy. J Cutan Pathol 2016;43: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153(7):694–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quaglino P, Marenco F, Osella-Abate S, et al. Vitiligo is an independent favourable prognostic factor in stage III and IV metastatic melanoma patients: results from a single-institution hospital-based observational cohort study. Ann Oncol 2010; 21(2):409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perret RE, Josselin N, Knol AC, et al. Histopathological aspects of cutaneous erythematous-papular eruptions induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Int J Dermatol 2017;56:527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaunitz G, Loss M, Rizvi H, et al. Cutaneous eruptions in patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade: clinicopathologic analysis of the nonlichenoid histologic pattern. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41(10):1381–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]