Abstract

The quality of family relationships and youth friendships are intricately linked. Previous studies have examined different mechanisms of family-peer linkage, but few have examined social anxiety. The present study examined whether parental rejection and family climate predicted changes in youth social anxiety, which in turn predicted changes in friendship quality and loneliness. Possible bidirectional associations also were examined. Data for mothers, fathers, and youth (Mage at Time 1 = 11.27; 52.3% were female) from 687 two-parent households over three time points are presented. Results from autoregressive, cross-lagged analyses revealed that father rejection (not mother rejection or family climate) at Time 1 (Fall of 6th Grade) predicted increased youth social anxiety at Time 2 (Spring of 7th Grade), which in turn, predicted increased loneliness at Time 3 (Spring of 8th Grade). The indirect effect of father rejection on loneliness was statistically significant. Mother rejection, father rejection, and a poor family climate were associated with decreased friendship quality and increased loneliness over time. Finally, there was some evidence of transactional associations between father rejection and youth social anxiety as well as between social anxiety and loneliness. This study’s findings underscore the important role of fathers in youth social anxiety and subsequent social adjustment.

Keywords: parental rejection, fathers, social anxiety, loneliness, friendship, peers

Introduction

Friendships are a highly salient feature of adolescent development (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011) and having supportive friendships is central to individuals’ well-being throughout the life course (Holt-Lunstad, 2017). Sullivan (1953) emphasized adolescents’ need for intimacy and interpersonal validation, and noted that this need is often fulfilled within friendships, and sets the foundation for subsequent close relationships. Empirical evidence has highlighted that friendships during adolescence contribute to adolescents’ social, emotional, and cognitive development (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). For instance, youth with more friends are more socially competent and psychologically healthy (Waldrip, Malcolm, & Jensen-Campbell, 2008). Beyond the quantity of friendships, the quality of friendships also matters for youth development (Erdley & Day, 2017; Waldrip et al., 2008). Relatedly, youth with poor quality friendships tend to have more internalizing and externalizing problems as well as poorer academic performance (Burk & Laursen, 2005). In the long run, youth with difficulty forming supportive friendships are likely to have more depressive symptoms and overall maladjustment in adulthood (Bagwell, Newcomb, & Bukowski, 1998)

Adolescence is characterized by multiple developmental transitions, which can create uncertainty, anxiety, and distress (La Greca & Ranta, 2015) and potentially impact adolescents’ strivings for peer acceptance, intimacy, and a clear sense of identity. For example, school transitions can disrupt adolescents’ existing peer support networks and require adolescents to develop new ones (La Greca & Ranta, 2015). At the same time, there is also a normative increase in fear of negative evaluation by peers in adolescence (Westenberg, Drewes, Goedhart, Siebelink, & Treffers, 2004). Not surprisingly, then, social fears are common in adolescence. In a community sample of adolescents and young adults, 43.3% of the youth reported feeling fearful in at least one social situation (Knappe et al., 2011). These normative increases in fears may make adolescents more likely to experience social anxiety, which includes 1) fear of negative evaluation, 2) avoidance and distress in new social situations, and 3) social distress and inhibition in general social situations (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). Social anxiety disorder – a severe form of social anxiety – has two peak onsets – late childhood and mid-adolescence (Knappe, Sasagawa, & Creswell, 2015). Nine percent of adolescents in the United States experience social anxiety in their lifetime (Merikangas et al., 2010).

The Role of Family for Social Anxiety

Family relationships are a formative context for developing social attitudes and skills and may influence the degree to which youth approach or avoid subsequent social relationships, an important aspect of social anxiety. Various aspects of family are associated with the development of social anxiety (Wong & Rapee, 2015). Parental rejection, characterized by low levels of affection, neglect, physical or verbal hostility, or other behaviors that leave youth feeling unloved, is theorized to influence youth’s mental representations about life, interpersonal relationships, and human existence (Rohner, 1986, 2004). Generally speaking, youth who perceive rejection from their parents are at elevated risk for depression, substance abuse, and behavioral problems (Rohner & Britner, 2002). Moreover, they tend to view interpersonal relationships as untrustworthy, unsafe, hostile, and threatening and may become hypervigilant and hypersensitive to rejection in other social relationships (Rohner, 2004); these experiences may lead them to feel more socially anxious. Parenting characterized by low parental warmth, high rejection, and high overprotection, are associated with youth social phobia (Knappe et al., 2009; Rudolph & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2014). Attachment theory postulates that youth, in the context of their relationships to their parents, develop attitudes and expectations that shape the formation and experience of interpersonal relationships outside of the family context (Bowlby, 1973). Youth with unstable or rejecting family relationships are more likely to develop insecure attachment style and are more likely to avoid social relationships or endure them with distress and fear. Infants with ambivalent attachment at the first year of life have more social anxiety symptoms at age 11 (Bar-Haim, Dan, Eshel, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2007) and are more likely to develop anxiety disorders at age 17, after controlling for mothers’ anxiety and youth temperament (Warren, Huston, Egeland, & Sroufe, 1997). Despite the progress made linking family experiences with social anxiety, this work largely presents a narrow view of family relationships: most studies have not considered father-child relationship and mother-child relationship independently, and the influence of the broader family climate has been largely neglected (e.g., Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Rudolph & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2014). Moreover, the relationship between parenting and social anxiety may be bidirectional, but this notion remains largely untested. Thus, at best, we have an incomplete picture of the role of family in influencing the development of social anxiety and quality of social relationships.

Family systems theorists have argued that a family consists of multiple subsystems as well as family-level functioning, and it is important to consider them when evaluating the role of family for individual development (Cox & Paley, 1997; Minuchin, 1985). All too often, research on parenting or parent-child relationships has focused on mother-child relations, and either ignores the potential contribution of fathers, or assumes that research on maternal parenting generalizes to fathers (Bögels & Phares, 2008). Yet, it is generally understood that there are differences in various dimensions of mother-child and father-child relationships, such as the amount of time spent together, content of interactions, and degree of closeness (Collins & Russell, 1991). Other work highlights fathers’ contribution to youth’s psychosocial adjustment (Lewis & Lamb, 2003), and in some cases, fathers’ parenting is more influential for youth adjustment than mothers’ parenting (e.g., Fosco, Stormshak, Dishion, & Winter, 2012; Padilla-Walker, Nielson, & Day, 2016). Therefore, it is important to understand both fathers and mothers’ contribution to youth’s social development. Beyond family dyadic relationships, other family factors such as coparenting are also related to youth anxiety (Majdandžić, de Vente, Feinberg, Aktar, & Bögels, 2012).

Family-level functioning has important implications for youth’s emotional development (Fosco & Grych, 2013) and anxiety, specifically (Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint, 2006). However, there is a dearth of research on how family-level functioning is related to youth social anxiety. To our knowledge, the only study that examines the link between family cohesion and social anxiety shows significant cross-sectional associations between them (Johnson, Lavoie, & Mahoney, 2001), suggesting that youth in families with closer and more supportive relationships are less socially anxious. In the current study, we focus on the family climate, defined as cohesion, organization, and (low levels of) conflict, expecting that it will be related to less social anxiety. Prior work has found that the family climate during adolescence has long-term implications for young adults’ competence in romantic relationships (Fosco, Van Ryzin, Xia, & Feinberg, 2016) as well as for young adult well-being (Fosco, Caruthers, & Dishion, 2012). Thus, family climate is a promising although understudied factor influencing social anxiety.

The Role of Social Anxiety for Social Adjustment

Social anxiety, even at subclinical levels, can be a significant barrier to the formation of positive peer relationships. It can lead youth to feel afraid of approaching peers, to avoid social interactions, or to experience significant distress while engaging in social interactions; not surprisingly, youth with higher social anxiety tend to experience less friendship support and peer acceptance (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). Youth with higher social anxiety are also more likely to withdraw socially, experience less companionship and intimacy from friends, and are more likely to refuse school (Biggs, Vernberg, & Wu, 2012; Nair et al., 2013). As social anxiety can undermine the formation of fulfilling friendships, adolescents may experience loneliness as a consequence. In fact, social anxiety and loneliness are commonly associated (Jones, Rose, & Russell, 1990). Social anxiety, especially the fear of negative evaluation from others, shares some conceptual overlap with rejection sensitivity, a term referring to individuals’ anxious expectation, immediate perception, and overreaction toward rejection from others (Downey, Bonica, & Rincon, 1999). Adolescents with higher rejection sensitivity show increases in depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as decreases in social competence (Marston, Hare, & Allen, 2010). Individuals who tend to anxiously expect rejection show increases in social anxiety and social withdrawal (London, Downey, Bonica, & Paltin, 2007).

Social Anxiety as a Potential Mechanism Linking Family and Social Adjustment

Family relationships are closely related to youth’s social functioning (Clark & Ladd, 2000). Exploring mechanisms can help us understand how family relationships influence subsequent friendships (Kerns, Contreras, & Neal-Barnett, 2000; Parke & Ladd, 1992) and thus provide more insight into how to support youth’s development of positive peer relations. Several individual factors have been identified as potential mechanisms linking family influences on peer relationships, such as attachment insecurity and emotion dysregulation (Schwarz, Stutz, & Ledermann, 2012), problem behaviors and emotional insecurity (Cook, Buehler, & Fletcher, 2012), prosocial orientation (Clark & Ladd, 2000), social self-efficacy (Coleman, 2003), and social information processing (Granot & Mayseless, 2012). Social anxiety is another potential mechanism through which family contribute to youth social adjustment, including their friendship quality and feelings of loneliness. Examining this mechanism can broaden our understanding on the difficulties that youth face growing up in suboptimal family environment and inform us ways to assist youth in their social adjustment.

Transactional Processes Among Family Relationships, Social Anxiety, and Social Adjustment

Family systems theorists propose that family influences are often circular, rather than unidirectional in nature (Minuchin, 1985), which suggests that there may be bidirectional associations among family relationships, social anxiety, and social adjustment. From this perspective, developmental models that conceptualize family relationships as exerting unidirectional influence on adolescent social anxiety may present only a fraction of the complete picture. Indeed, in addition to the possibility that parental rejection and family climate predict changes in youth social anxiety, it is also possible that youth social anxiety predicts changes in parental rejection and family climate, an area that is much understudied. Beyond family interactions, social anxiety and social adjustment are intertwined such that social anxiety predicts changes in social adjustment and social adjustment in turns predict changes in social anxiety (Vernberg, Abwender, Ewell, & Beery, 1992). Therefore, consistent with the transactional perspective of development (Sameroff, 2009), it is important to examine possible transactional associations between individuals and their developmental contexts.

Current Study

In order to examine how family functioning is related to adolescent friendship quality and feeling of loneliness, we evaluated social anxiety as an explanatory mechanism. Specifically, we hypothesized that higher levels of father rejection, mother rejection, and lower levels of positive family climate at Time 1 (T1; Fall of 6th Grade) would predict increases in adolescent social anxiety at Time 2 (T2; Spring of 7th Grade), which would in turn predict decreases in friendship quality and increases in loneliness at Time 3 (T3; Spring of 8th Grade). To avoid assumptions of unidirectional processes, we evaluated these research questions within a transactional framework by testing bidirectional associations among family relationships, social anxiety, and social adjustment in cross-lagged models. Finally, we examined the possibility of gender moderation of these processes given that adolescent girls are more likely to experience social anxiety symptoms than boys (Wittchen, Stein, & Kessler, 1999) and other work points to gender differences in peer socialization processes (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). In fact, cross-sectional evidence suggests that social anxiety is more strongly correlated with social functioning for girls than for boys (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). We extend this work by examining gender differences in our longitudinal models.

The present study addressed some important limitations in the literature. First, we examined mothers and fathers separately to better evaluate impact of each parent’s rejection on youth social anxiety and social adjustment. Second, we tested the effect of family climate; an aspect of family functioning that has largely been overlooked in studies of youth social development. Third, we employed a multi-informant design to present a more comprehensive assessment of family functioning. Fourth, we used a cross-lagged model approach to conduct a stringent test of our hypotheses and to avoid assumptions of directionality. Finally, we controlled for youth internalizing symptoms at T1 because of evidence suggesting high rates of comorbidity between social anxiety and depression (Epkins & Heckler, 2011).

Methods

Participants

This study reports on a secondary analysis of data from the large-scale randomized trial of the Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) intervention delivery system. The parent study was an effectiveness trial of preventive interventions that aimed at preventing substance use among rural youth (Spoth, Greenberg, Bierman, & Redmond, 2004). Participants in PROSPER were from 28 rural and semi-rural communities in Iowa and Pennsylvania. Community prevention teams in intervention communities implemented a sequence of evidence-based programs: a family-based intervention offered to all sixth graders’ families and a school-based curriculum delivered to these students in seventh grade. The PROSPER project recruited two successive cohorts of sixth graders with 1 year apart (2002 and 2003).

The current study draws on a subsample of youth that participated in the intensive in-home assessment. Families were randomly selected from second cohort of sixth graders and invited to the in-home data collection. Of those invited (N = 2,267 families), 977 families participated in the in-home study. We compared our in-home subsample to the cohort of youth in the original sample from which it was drawn to see how well our subsample represented the bigger sample. Out of the 977 in-home participants, 896 youth have participated in both in-home and in-school data collection at T1. We used t-tests to compare these participants to the rest of the in-school only participants on three domains. Results showed that the two samples were comparable on enrollment in free or reduced-price lunch program (t (5260) = 0.43, p > .05), family climate (t (4688) = 2.04, p < .05, with Cohen’s d of .08, indicating a very small effect size), and school adjustment bonding (t (5336) = 3.03, p < .05, with Cohen’s d of .11, indicating a very small effect size). In-home assessment included paper questionnaires completed separately by the youth, the mother, and the father. Because this study focused on two-parent households, we selected only families in which parents reported being “married or in a marriage-like relationship,” and headed by a mother and a father (e.g., families with grandparents as caregivers were excluded from analysis). This resulted in a final sample of 687 families at T1. In these families, “mother” was defined as those who identified their relationship to the target youth as mothers (97.5%), stepmothers (1.5%), or female adoptive parents (1%); “fathers” were those who described their relationship to the youth as fathers (80.2%), stepfathers (18.5%), or male adoptive parents (1.3%). Out of the 687 families, 610 fathers (88.8%) participated. Youth participants included 357 girls (52.3%), 326 boys (47.7%), and 4 youth with missing data on gender. Three measurement occasions were included in the current study: T1 (N = 687) occurred in the Fall of 6th Grade in 2003, T2 (N = 567; 82.5% retained) was the Spring of 7th Grade in 2005, and T3 (N = 548; 79.8% retained from T1) was the Spring of 8th Grade in 2006. Measurement occasions were spaced 1.5 years (T1 to T2) and 1 year (T2 to T3) apart. Mean participant ages at T1 were: youth (M = 11.27, SD = 0.49); mothers (M = 38.93, SD = 5.56); and fathers (M = 41.24, SD = 6.75). The median household income was $55,000 (8.2% missing). For 68.2% of youth, their parents had postsecondary education. Youth reported their race as White (90%), Hispanic (6.3%), African American (1.2%), Asian (0.6%), and others (1.9%).

Measures

Parental rejection.

Parental rejection toward youth was measured by five items adapted from the Elliott’s parental rejection scale (Brennen, 1974). Fathers and mothers reported separately on their own rejecting beliefs toward youth, including seeing faults and problems in them (e.g., “I feel this child has a number of faults”), distrust (e.g., “I really trust this child”; reversed coded), low level of love (e.g., “I experience strong feelings of love for this child”; reversed coded), and general dissatisfaction (e.g., “I am dissatisfied (unhappy) with the things he or she does”). Mothers and fathers rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1-strongly agree, 2-agree, 3-neutral of mixed, 4-disagree, to 5-strongly disagree; items were averaged and scaled so that higher values reflect greater parental rejection. The reliabilities were acceptable, with Cronbach’s alphas of .78 (T1), .79 (T2), .80 (T3) for fathers and .76 (T1), .83 (T2), .82 (T3) for mothers.

Family climate.

Family climate was assessed with 13 items drawn from the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1994), and included aspects of family cohesion (e.g., “Family members really help and support each other”), conflict (e.g., “we fight a lot in our family”), and organization (e.g., “We are generally very neat and orderly”). Fathers and mothers rated separately on a 5-point scale, from 1-strongly agree, 2-agree, 3-neutral or mixed, 4-disagree, to 5-strongly disagree. The scale was scored with higher values indicating better family climate. Mothers’ and fathers’ scores were averaged for subsequent analyses. Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable for fathers’ (T1 = .83, T2 = .85, T3 = .82) and mothers’ (T1 = .82, T2 = .83, T3 = .83) ratings of family climate.

Youth social anxiety.

Youth completed the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998). This measure consists of 18 items from three subscales: a) fear of negative evaluation from peers (8 items – e.g., “I worry about what others think of me”), b) social avoidance and distress in new social situations (6 items – e.g., “I get nervous when I meet new people”), and c) social avoidance and distress in general social situations (4 items – e.g., “I feel shy even with peers I know very well”). Youth rated how true each item was for them on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1-not at all, 2-hardly ever, 3-sometimes, 4-most of the time, to 5-all the time. All 18 items were averaged to form a total social anxiety score with higher values representing more social anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients were acceptable: .93 at T1, .94 at T2, and .95 at T3.

Friendship quality.

Youth responded to an 8-item adapted version of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire (Parker & Asher, 1993), which has evidence of validity in its shortened form (Tu, Erath, Pettit, & El-Sheikh, 2014). The shortened form of this measure was used to assess the degree to which youth felt cared and supported by friends (e.g., “my friends care about me”), the degree to which they trusted their friends (e.g., “I can always count on my friends to keep promises”), and got along with their friends (e.g., “my friends and I argue a lot; reversed coded). Youth rated items on a 5-point scale, from 1-not at all true, 2-a little true, 3-somewhat true, 4-mostly true, to 5-really true. Items were averaged and higher values reflect higher friendship quality. The Cronbach’s alphas were .78 at T1, .80 at T2, and .81 at T3.

Loneliness.

Youth responded to three items selected from Children’s Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale (Asher, Hymel, & Renshaw, 1984; Asher & Wheeler, 1985) regarding their feeling of loneliness at school (e.g., “I am lonely at school”). Youth rated on a 5-point scale, from 1-not at all true, 2-a little true, 3-somewhat true, 4-mostly true, to 5-really true. Items were averaged and higher values indicate more loneliness. The Cronbach’s alphas were .92 at T1, .94 at T2, and .94 at T3.

Covariates.

We included household income, parents’ education level, and youth’s race as covariates as these variables predicted attrition in this sample. In addition, we included youth’s gender, living with both biological parents, and youth internalizing symptoms at T1 as covariates. Family income was scored from 1 to 10 in $10,000 intervals, or 11 if income was over $100,000. Parents’ education level was scored from 0 to 20: 0 (no grade completed), 1–16 (each year of education from first grade through completion of a bachelor’s degree), 17 (education beyond a bachelor’s degree), 18 (master of science/master of arts), 19 (education beyond a master’s degree), to 20 (doctoral degree). Youth race was coded as 0 (White) or 1 (non-White). Youth gender was coded as 0 (female) or 1 (male). Youth who lived with both biological parents were coded as 1 and youth who lived with at least one non-biological parent were coded as 0. Geographical location was coded as 0 (Pennsylvania) or 1 (Iowa). Youth internalizing symptoms was measured by the 16-item depressed/anxious subscale of Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991). Youth rated on a 3-point scale, from 0-not true, 1-somewhat or sometimes true, to 2-very true or often true. Items were averaged so that higher values indicate more internalizing problems. The Cronbach’s alpha is .85 at T1, .89 at T2, and .90 at T3.

Analysis Plan

After computing correlations and descriptive statistics, structural equation models were estimated using Mplus 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014). We then evaluated whether attrition in the sample resulted in bias and identified demographic factors that could account for attrition. Finally, we estimated models using Full Information Maxiumum Likelihood estimation techniques to minimize bias due to missing data (Widaman, 2006).

We computed three autoregressive cross-lagged models for father rejection, mother rejection, and family climate separately. In these models, we controlled for household income, parents’ education level, youth’s race, youth’s gender, living with both biological parents, and youth internalizing symptoms at T1 by allowing them to correlate with all T1 variables and having all T2 and T3 variables regressed on these covariates. Variables at each time point were allowed to correlate with one another. Model fit statistics were examined for each model first using chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), non-normed or Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Models were determined to have good fit with the data if CFI and TLI values > .95, RMSEA value <.06, and SRMR value < .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For models that demonstrated good fit with the data, standardized path coefficients were examined. Indirect effects for specific hypothesized paths were examined using bootstrap samples of 5000 and 95% confidence intervals.

Subsequently, we conducted multi-group invariance tests to determine if the overall models differed across groups in two ways. First, we tested whether the model differed for families in the intervention and control groups. Second, we tested whether the models were different for boys and girls. Invariance tests were conducted in two steps, first by estimating models with the path coefficients freely estimated across groups, and then by constraining all paths to be the same for both groups. Model fit comparisons across the freely estimated model and the fully constrained model were conducted using a χ2 difference test. If the freely estimated models and the fully constrained models were invariant across intervention and control groups, it would be appropriate to retain the full sample in the analyses to maximize power. Before conducting invariance tests across boys and girls, gender was taken out of models as a covariate prior to subjecting the models to gender invariance tests. If differences were detected, it indicated gender differences in one or more structural paths in the model. Modification indices would then be examined to identify paths with significant differences (p < .01) and those paths would be explored for gender moderation; otherwise, if no differences emerged, it was determined that the model was representative of the full sample.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were reported in Table 1. As expected, higher levels of mother and father rejection were associated with more social anxiety; more positive family climate was associated with less social anxiety, and higher levels of social anxiety were associated with lower friendship quality and more loneliness.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. F. Rej T1 | .78 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. F. Rej T2 | .71* | .79 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. F. Rej T3 | .65* | .69* | .80 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. M. Rej T1 | .56* | .51* | .45* | .76 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. M. Rej T2 | .54* | .60* | .53* | .75* | .83 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. M. Rej T3 | .46* | .49* | .51* | .70* | .76* | .82 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Fam T1 | −.46* | −.39* | −.36* | −.42* | −.42* | −.36* | .88 | |||||||||||||||||

| 8. Fam T2 | −.41* | −.42* | −.34* | −.41* | −.45* | −.39* | .75* | .89 | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Fam T3 | −.38* | −.41* | −.42* | −.37* | −.45* | −.40* | .70* | .80* | .88 | |||||||||||||||

| 10. Sanx T1 | .21* | .28* | .28* | .23* | .24* | .20* | −.18* | −.19* | −.17* | .93 | ||||||||||||||

| 11. Sanx T2 | .26* | .24* | .24* | .21* | .19* | .16* | −.20* | −.17* | −.17* | .58* | .94 | |||||||||||||

| 12. Sanx T3 | .25* | .28* | .23* | .14* | .16* | .15* | −.18* | −.17* | −.17* | .50* | .64* | .95 | ||||||||||||

| 13. Frd T1 | −.20* | −.22* | −.23* | −.20* | −.22* | −.21* | .16* | .16* | .14* | −.34* | −.24* | −.25* | .78 | |||||||||||

| 14. FrdT2 | −.20* | −.22* | −.19* | −.17* | −.22* | −.17* | .22* | .16* | .15* | −.19* | −.35* | −.26* | .38* | .80 | ||||||||||

| 15. Frd T3 | −.20* | −.24* | −.20* | −.19* | −.25* | −.22* | .17* | .18* | .20* | −.15* | −.26* | −.33* | .33* | .48* | .81 | |||||||||

| 16. Lone T1 | .24* | .24* | .28* | .20* | .24* | .22* | −.12* | −.13* | −.12* | .41* | .33* | .29* | −.36* | −.29* | −.22* | .92 | ||||||||

| 17. Lone T2 | .26* | .22* | .23* | .26* | .25* | .20* | −.20* | −.19* | −.18* | .30* | .45* | .39* | −.24* | −.46* | −.38* | .39* | .94 | |||||||

| 18. Lone T3 | .25* | .26* | .25* | .19* | .20* | .18* | −.13* | −.12* | −.12* | .24* | .32* | .45* | −.16* | −.27* | −.36* | .26* | .44* | .94 | ||||||

| 19. Hinc T1 | −.20* | −.20* | −.21* | −.18* | −.18* | −.19* | .14* | .17* | .18* | −.17* | −.14* | −.14* | .15* | .04 | .06 | −.10* | −.11* | −.09* | -- | |||||

| 20. Pedu T1 | −.24* | −.16* | −.16* | −.18* | −.16* | −.08 | .11* | .11* | .15* | −.15* | −.06 | −.12* | .10* | −.01 | .03 | −.07 | −.06 | −.01 | .51* | -- | ||||

| 21. Y. Race | −.05 | −.08 | −.01 | −.01 | −.02 | .07 | .08* | .07 | .09* | .01 | −.03 | .00 | −.02 | .02 | .08* | −.05 | −.02 | −.07 | −.08* | −.10* | -- | |||

| 22. Y. Gend | .06 | .05 | .00 | .09* | .09* | .01 | .00 | −.03 | −.02 | −.11* | −.08 | −.08 | −.16* | −.27* | −.25* | .00 | .07 | .04 | .07 | .04 | −.03 | -- | ||

| 23. 2-Bio T1 | −.27* | −.20* | −.31* | −.12* | −.17* | −.20* | .13* | .21* | .17* | −.15* | −.10* | −.06 | .11* | −.02 | −.02 | −.04 | −.02 | −.03 | .15* | .09* | −.06 | .09* | -- | |

| 24. Y. Int T1 | .20* | .27* | .23* | .21* | .24* | .22* | −.22* | −.15* | −.10* | .45* | .32* | .32* | −.26* | −.22* | −.19* | .33* | .30* | .26* | −.07 | .00 | .00 | −.07 | −.14* | -- |

| M | 1.65 | 1.64 | 1.64 | 1.56 | 1.55 | 1.56 | 3.74 | 3.68 | 3.69 | 2.24 | 2.15 | 2.13 | 4.19 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 1.56 | 1.58 | 1.56 | 6.05 | 13.31 | 1.21 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.20 |

| SD | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 2.49 | 2.21 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.25 |

Note. F. Rej = Father Rejection, M. Rej = Mother Rejection, Fam = Family Climate, Sanx = Youth Social Anxiety, Frd = Friendship Quality, Lone = Loneliness, Hinc = Household Income, Pedu. = Parents’ Education Level, Y. Race = Youth’s Race, Y. Gend = Youth’s Gender, 2-Bio = Living with Both Biological Parents, Y. Int = Youth Internalizing Symptoms. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation.

= p < .05. The coefficients on the diagonal in bold are Cronbach’s alphas.

The Little’s MCAR test was significant, χ2 (623) = 810.36, p < .001, suggesting that the data were not missing completely at random. We conducted t-tests to compare attriters to completers at T2 and T3 on all the baseline variables in the model and covariates (household income, parents’ education level, and youth’s race, youth’s gender, living with both biological parents, and geographical location). Of these, low family income (t (629) = −3.60), low parent education (t (674) = −7.10), and youth ethnic minority status (t (141.60) = 3.38) were significantly related to attrition at T2 (p’s < .05). Similarly, low family income (t (629) = −2.36), low parent education (t (674) = −5.35), and youth ethnic minority status (t (176.69) = 2.66) were significantly related to attrition at T3 (p’s < .05). These covariates, together with other control variables, were included in structural path models, which were estimated using full information maximum likelihood to reduce potential bias of missing data (Widaman, 2006).

The first model, for father rejection, is presented in Fig. 1 and yielded good fit with the data, where X2 (12) = 10.14, p = .60, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: [.000, .034]), and SRMR = .01. Father rejection at T1 was associated with increases in social anxiety at T2 (β = .12, p < .01), but father rejection at T2 was not associated with changes in social anxiety at T3 (β = .07, p < .06). Social anxiety at T1 was associated with increases in loneliness at T2 (β = .10, p < .05) and social anxiety at T2 was also associated with increases in loneliness at T3 (β = .10, p < .05). To test the hypothesis that social anxiety (T2) mediated the association between father rejection (T1) and loneliness (T3), we tested the indirect effect. Results from bootstrapping (R = 5000) showed that the standardized indirect effect of father rejection at T1 on loneliness at T3 via social anxiety at T2 was significant (standardized indirect effect = .01) and the 95% CI did not contain zero [.001 to .046]). Contrary to our hypotheses, social anxiety was not associated with changes in friendship quality at either subsequent time point. In addition, father rejection at T1 was directly associated with decreases in friendship quality (β = −.09, p < .05) and increases in loneliness at T2 (β = .13, p < .01). At T2, father rejection was associated with increases in loneliness at T3 (β = .12, p < .01) but was not associated with friendship quality.

Fig. 1. Cross-lagged model among father rejection, social anxiety, friendship quality, and loneliness.

Note. Path coefficients reflect standardized betas; solid lines reflect statistically significant paths (p < .05). + p < .06. Dotted lines are not statistically significant. Model fit: χ2 (12) = 10.14, p = .604; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: [.000, .034]), SRMR = .007. Covariates included in the model (not depicted in figure for ease of presentation): Household income, parents’ education level, youth’s race, youth’s gender, living with both biological parents, and youth internalizing symptoms. Variables at each time point were allowed to correlate with one another (arrows not shown in figure). The path from loneliness at T2 to social anxiety at T3 was significant for boys (β = .22) but not girls (β = .01).

Upon examination of bidirectional paths in the cross-lagged model, some support for a transactional relationship between father rejection and social anxiety emerged. Specifically, social anxiety at T1 was associated with increases in father rejection at T2 (β = .08, p < .05), however the effect was somewhat small and there was no evidence for such an effect from T2 social anxiety to T3 father rejection. In addition, bidirectional associations between loneliness and social anxiety were found across all measurement occasions. Accounting for the paths linking social anxiety on loneliness, loneliness at T1 was associated with increases in social anxiety at T2 (β = .09, p < .05) and loneliness at T2 was associated with increases in social anxiety at T3 (β = .12, p < .01). Finally, loneliness at T1 was associated with decreases in friendship quality at T2 (β = −.14, p < .01) and loneliness at T2 was associated with decreases in friendship quality at T3 (β = −.17, p < .001). Overall, the variance explained (R2) in model outcomes ranged from .22 to .59 (see Fig. 1). The multigroup invariance test showed no differences in model paths between intervention and control group (Δχ2 (84) = 96.87, p = .16). The multipgroup invariance test examining gender differences showed that the freely estimated model fitted significantly better than the fully constrained model (Δχ2 (76) = 111.66, p = .00), suggesting gender differences in two model paths. Specifically, youth internalizing symptoms at T1 was associated with increases in loneliness at T2 (a covariate path) for boys (β = .23, p < .001), but not girls (β = .07, p = .25). Also, loneliness at T2 was associated with increases in social anxiety at T3 for boys (β = .22, p < .001), but not girls (β = .01, p = .79). After the two paths were freed, the freely estimated model was no longer significantly different from the fully constrained model (Δχ2 (74) = 94.42, p = .06), suggesting that the other paths in this model did not differ for boys and girls.

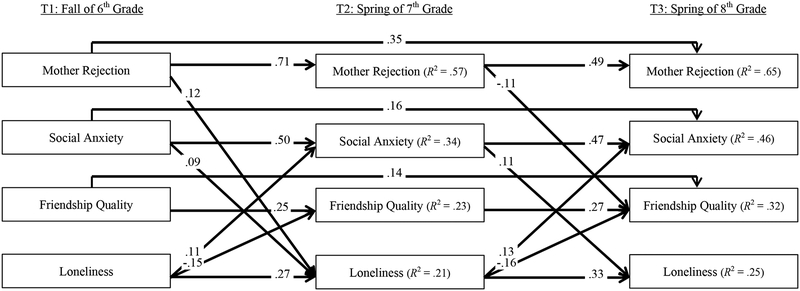

The second model included mother rejection. As presented in Fig. 2, this model yielded good fit with the data, where X2 (12) = 9.42, p = .67, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: [.000, .031]), and SRMR = .01. Related to the primary hypothesis, this model did not find a statistically significant association between mother rejection and social anxiety at either time point. However, mother rejection at T1 was associated with increases in loneliness at T2 (β = .12, p < .01), and mother rejection at T2 was associated with decreases in friendship quality at T3 (β = −.11, p < .01). Similar to the previous model, there were significant reciprocal associations among social anxiety and loneliness from T1 to T2 and T2 to T3. Loneliness at T1 was associated with decreases in friendship quality at T2 (β = −.15, p < .001) and loneliness at T2 was associated with decreases in friendship quality at T3 (β = −.16, p < .001). The variance explained (R2) in model outcomes ranged from .21 to .65 (see Fig. 2). The multigroup invariance test showed no differences in model paths between intervention and control group (Δχ2 (84) = 73.75, p = .78). The multipgroup invariance test examining gender differences indicated that the freely estimated model fitted significantly better than the fully constrained model (Δχ2 (76) = 103.35, p = .02), suggesting gender differences in two same model paths as in the previous model. Youth internalizing symptoms at T1 was associated with increases in loneliness at T2 (a covariate path) for boys (β = .22, p < .001), but not girls (β = .06, p = .27). Also, loneliness at T2 was associated with increases in social anxiety at T3 for boys (β = .22, p < .001), but not girls (β = .02, p = .71). After the two paths were freed, the freely estimated model was no longer significantly different from the fully constrained model (Δχ2 (74) = 86.84, p = .15).

Fig. 2. Cross-lagged model among mother rejection, social anxiety, friendship quality, and loneliness.

Note. Path coefficients reflect standardized betas; solid lines reflect statistically significant paths (p < .05). Dotted lines are not statistically significant. Model fit: χ2 (12) = 9.42, p = .666; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: [.000, .031]), SRMR = .006. Covariates included in the model (not depicted in figure for ease of presentation): Household income, parents’ education level, youth’s race, youth’s gender, living with both biological parents, and youth internalizing symptoms. Variables at each time point were allowed to correlate with one another (arrows not shown in figure). The path from loneliness at T2 to social anxiety at T3 was significant for boys (β = .22) but not girls (β = .02).

The third model included family climate (Model 3) is shown in Fig. 3. This model yielded good fit with the data, where X2 (12) = 8.83, p = .72, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: [.000, .029]), and SRMR = .01. Contrary to our hypotheses, family climate was not associated with subsequent changes in social anxiety at either time point. However, positive family climate at T1 was directly associated with increases in friendship quality (β = .15, p < .001) and decreases in loneliness (β = −.10, p < .05) at T2 and positive family climate at T2 was associated in increases in friendship quality at T3 (β = .09, p < .05). Similar to the previous models, there were significant reciprocal associations among social anxiety and loneliness across all occasions and loneliness was associated with decreases in friendship quality across all occasions. The variance explained (R2) in outcomes ranged from .21 to .67 (see Fig. 3). The multigroup invariance test showed no differences in model paths between intervention and control group (Δχ2 (84) = 92.80, p = .24). The multipgroup invariance test examining gender differences showed that the freely estimated model fitted significantly better than the fully constrained model (Δχ2 (76) = 98.80, p = .04). Similar to the prior models, two paths differed for boys and girls: The association between T1 internalizing symptoms and T2 loneliness (boys: β = .23, p < .001; girls: β = .06, p = .27) and the path between T2 loneliness and T3 social anxiety (boys: β = .22, p < .001; girls: β = .01, p = .82). After the two paths were freed, the freely estimated model was no longer significantly different from the fully constrained model (Δχ2 (74) = 80.92, p = .27).

Fig. 3. Cross-lagged model among family climate, social anxiety, friendship quality, and loneliness.

Note. Path coefficients reflect standardized betas; solid lines reflect statistically significant paths (p < .05). Dotted lines are not statistically significant. Model fit: χ2 (12) = 8.83, p = .718; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: [.000, .029]), SRMR = .006. Covariates included in the model (not depicted in figure for ease of presentation): Household income, parents’ education level, youth’s race, youth’s gender, living with both biological parents, and youth internalizing symptoms. Variables at each time point were allowed to correlate with one another (arrows not shown in figure). The path from loneliness at T2 to social anxiety at T3 was significant for boys (β = .22) but not girls (β = .01).

Discussion

The quality of family relationships has significant implications for youth’s friendships. Different aspects of parenting and parent-adolescent relationship are associated with the development of youth social anxiety (Knappe et al., 2009), and social anxiety is a significant barrier in youth social adjustment (Biggs et al., 2012). Most work on family relationships and youth social anxiety has not considered fathers’ and mothers’ contribution separately and family-level functioning has generally been overlooked. Most importantly, prior work has not tested social anxiety as a mechanism through which different family factors are associated with youth social adjustment and transactional associations remain largely unexamined. The current study expands on the extant literature by testing social anxiety as a mechanism by which parental rejection and family climate predict changes in youth’s friendship quality and loneliness via changes in social anxiety. We used a multi-informant approach and conducted our analyses using three-wave cross-lagged models. We found that father rejection, but not mother rejection or family climate, predicted changes in social anxiety in youth. We also found significant indirect associations between levels of father rejection and increases in loneliness via increases in social anxiety, supporting our mediational hypothesis. Our findings suggest that father rejection may lead youth to be more fearful and avoidant of social situations, which in turn may lead to more social isolation. There was some evidence for a reciprocal association in which youth social anxiety predicted later father rejection, but the effect was small. Consistent across all three models, family factors (i.e., father rejection, mother rejection, and family climate) were each directly associated with youth social adjustment. There are also consistent transactional associations between social anxiety and loneliness across models. Finally, loneliness predicted subsequent decreases in friendship quality in all three models.

These findings highlight the unique role fathers play in youth social anxiety and social adjustment, which is consistent with other research on father-adolescent relationship and social development (Rice, Cunningham, & Young, 1997). Bögels & Phares (2008) suggest that fathers have unique developmental influence on youth anxiety from childhood to adolescence. For instance, in childhood, children with secure attachment with fathers, but not mothers, tend to approach rather than avoid new social situations. Also, fathers often establish the role of a playmate and fathers’ play sometimes encourages youth to practice approaching novel social situations. In adolescence, fathers’ closeness and involvement is a stronger predictor than mothers’ closeness and involvement in protecting youth from psychological distress. Other work has found that changes in time spent with fathers during childhood and adolescence predict changes in social competence and self-worth (Lam, McHale, & Crouter, 2012). Therefore, youth who experience more father rejection may not benefit from the social training that comes from a close and involved relationship to achieve a series of social developmental milestones, and this may undermine their comfort in social situations and their ability to develop fulfilling friendships. The contribution of youth social anxiety to parental rejection has received little attention in past research. Our findings suggest some evidence for reciprocal relationship between social anxiety and father rejection, although the child-directed effect appears to be weak.

Although we expected mothers’ rejection to be associated with social anxiety, the null finding for mother rejection and social anxiety has emerged in other studies. For example, Knappe, Beesdo-Baum, Fehm, Lieb, and Wittchen (2012) found the same pattern of results as the current study: father rejection, but not mother rejection, was associated with youth social anxiety. However, Knappe and colleagues found support for mothers’ overprotective parenting as a predictor of social anxiety, suggesting other avenues of mother influence on youth social anxiety. Nonetheless, prior work converges with our findings that mother rejection may not be a key predictor of social anxiety in early adolescence.

However, it may be the case that there may be issues of developmental timing for mother rejection such that its influence may be more pronounced in childhood. The proposition of developmental timing is consistent with accruing evidence that mothers’ parenting is associated with children’s adjustment but the association appears to wane into adolescence. It seems that during adolescence, fathers’ parenting may become more influential in adolescent and young adult adjustment and social relationships (Lamb & Lewis, 2010). This highlights the importance of including fathers in prevention and intervention efforts that target improving adolescents’ social and psychological well-being.

Our hypothesized model on parental rejection influencing youth social adjustment fit with some of the propositions advanced by attachment theory. Prior work on attachment has shown that ambivalent attachment in infancy is associated with social anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in adolescence (Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Warren et al., 1997). However, these studies measured attachment in infancy and focused on mothers. It remains to be seen whether attachment with parents in adolescence may have the same effect as parental rejection on adolescent social anxiety. Nevertheless, there are some significant differences between parental rejection and attachment. Parental rejection in this study focuses on parents’ rejecting attitudes towards their youth whereas attachment insecurity is conceptualized as individuals’ internal working models toward social relationships. In fact, future research may examine whether individuals’ internal working model mediates the relationships between parental rejection and social anxiety.

Family factors were also directly related social adjustment in the current study. One possible explanation is that there may be other unmeasured pathways by which father rejection, mother rejection, and family climate impact friendship quality and feelings of loneliness. Parental rejection and family climate may undermine youth’s developing self-worth or self-esteem, which may lead them to feel socially isolated. In fact, youth from families with high cohesion show higher self-efficacy and problem-solving skills in their social relationships (Leidy, Guerra, & Toro, 2012), which are likely to contribute to better friendship quality and less loneliness. Unmeasured pathways are also likely to include mechanisms identified by prior work in explaining associations between family and peer relationships, such as attachment insecurity and emotion dysregulation (Schwarz et al., 2012), problem behaviors and emotional insecurity (Cook et al., 2012), prosocial orientation (Clark & Ladd, 2000), and social information processing (Granot & Mayseless, 2012). Future research should also explore peer rejection as a mechanism. Youth may acquire rejecting attitudes and behaviors through their experiences with their parents and engage in similar behaviors with their peers, resulting in peer rejection, and ultimately poor friendship quality and loneliness. In fact, peer rejection has shown to predict decreases in friendship quality and increases in loneliness and rejection sensitivity (London et al., 2007; Pedersen, Vitaro, Barker, & Borge, 2007). More work is needed to help illuminate additional potential pathways through which family influences youth social adjustment.

Our analyses revealed consistent reciprocal associations between youth social anxiety and loneliness. This suggests that it is not only social anxiety that leads to loneliness, but feeling lonely and emotionally distant from friends may also escalate feelings of social anxiety, suggesting a cyclical process in which social anxiety begets isolation, which begets more social anxiety, further perpetuating social maladjustment. Loneliness may also heighten the salience of achieving positive interactions with peers for a youth, thus raising the stakes for peer interactions. Our findings add to a literature that has documented the association between social anxiety and loneliness, but struggled to disentangle the cause and effect relationship (Jones et al., 1990). A transactional relationship not only clarifies this issue, but also offers support for interventions that focus on increasing social interactions (thereby decreasing loneliness) as a means of reducing social anxiety.

The hypothesized associations among changes in family factors, social anxiety, and social adjustment were generally invariant across gender. This suggests that the process model of parental rejection and family climate predicting changes in social anxiety, and in turn predicting changes in friendship quality and loneliness was mostly the same for boys and girls. There were two paths indicating gender differences. The first path was a covariate path from youth internalizing symptoms at T1 to loneliness at T2, which was not the focus of the present study. The second path indicated that loneliness at T2 is likely to escalate feelings of social anxiety at T3 for boys but not girls. Given prior cross-sectional work has shown that social anxiety is more strongly associated with support, intimacy, and companionship in close friendships in adolescent girls (La Greca & Lopez, 1998), we expect girls to show stronger association between social anxiety and loneliness. However, our findings indicated otherwise. Our longitudinal findings suggest that regardless of gender, youth with higher social anxiety are likely to be lonelier, however, loneliness is relatively less robust in predicting social anxiety in girls than in boys. Nevertheless, we call for future longitudinal replications.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample consisted of primarily White, rural families; this limits the generalizability to urban families or families of other ethnic backgrounds. Youth from other ethnic groups may experience social anxiety or peer victimization differently. Future research should examine the effect of parental rejection and family climate on youth social anxiety and social adjustment with a more diverse sample or in other ethnic groups. Second, we only included parental rejection as the only parenting factor in predicting social anxiety. Future research may extend this to include other parenting factors such as parental overprotection, which has been shown to influence youth social anxiety (Knappe et al., 2012). Third, our findings showed that father rejection predicted increases in social anxiety, but did not examine the mechanism under which this happened. Future research should examine possible pathways, including the development of social mental representations and self-worth. Fourth, the effect sizes of our findings were generally small, however, the results should be interpreted in the light that autoregressive cross-lagged models are very conservative. Adachi and Willoughby (2015) has pointed out that regression coefficients in autoregressive cross-lagged models are generally small because so much of the variance is accounted for in the autoregressive paths. Nonetheless, small coefficients can be meaningful, especially when the bivariate correlation between the predictor and the outcome at the earlier time point is not small and the stability coefficient is high. In our case, we had moderate correlations between father rejection and social anxiety (r = .21 and .24 at T1 and T2 respectively) and a moderate to high stability coefficient in social anxiety (β = .50 and .47 for the first and second lags respectively). Fifth, these data were collected between 2003 and 2006 and there may be possible cohort differences from present-day families. Finally, youth social anxiety and friendships may be influenced by school transition, for instance, during sixth grade (T1). However, we had not collected data prior to the transition to allow for such analyses.

Conclusion

Guided by a family systems framework, the present study examined cross-lagged models in which family factors predicted changes in youth social anxiety, and in turn, predicted changes in youth social adjustment. This study draws on several strengths. First, it offered a multi-dimensional assessment of the family, including family-level functioning, mothers’ rejection, and fathers’ rejection, allowing for inference about the contribution of each to youth social anxiety and social adjustment during the early-to-middle adolescent years. Second, we conducted conservative tests of our hypotheses, including a multi-informant approach to disentangle method variance and three-wave cross-lagged models to capture changes over time. Third, we examined transactional associations among family factors, social anxiety, and youth social adjustment. Lastly, we controlled for baseline internalizing symptoms when examining associations between family and social anxiety because social anxiety has been consistently found to co-occur with depression (Epkins & Heckler, 2011).

This study provides important contributions to the literature on the associations among family, youth social anxiety, and social adjustment. Our findings suggest that fathers play a crucial role in youth social adjustment, especially through helping youth feel comfortable in approaching social relationships. Also, our work provides insights into transactions among father rejection, youth social anxiety, and youth social functioning. Finally, our findings support the view that families continue to play vital roles in youth’s social adjustment.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the participating youth and families, and the PROSPER staff, to the success of this project.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01 DA013709) and co-funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant R01 AA14702). Additional support was provided by the Karl R. and Diane Wendle Fink Early Career Professorship for the Study of Families (to G.M.F.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were approved by the local institutional review board.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all parents included in the study

Contributor Information

Hio Wa Mak, Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University, 119 Health and Human Development Building, University Park, PA 16802.

Gregory M. Fosco, Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University, 226 Health and Human Development Building, University Park, PA 16802, Phone: 814-865-5622, Fax: 814-863-7963, gmf19@psu.edu

Mark E. Feinberg, Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, 314 Biobehavioral Health Building, University Park, PA 16802, mef11@psu.edu

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi P, & Willoughby T (2015). Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 116–128. 10.1080/17405629.2014.963549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Hymel S, & Renshaw PD (1984). Loneliness in children. Child Development, 55, 1456–1464. 10.2307/1130015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, & Wheeler VA (1985). Children’s loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 500–505. 10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Newcomb AF, & Bukowski WM (1998). Preadolescent friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. Child Development, 69, 140–153. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, & Schmidt ME (2011). Friendships in childhood and adolescence. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Dan O, Eshel Y, & Sagi-Schwartz A (2007). Predicting children’s anxiety from early attachment relationships. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 1061–1068. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs BK, Vernberg EM, & Wu YP (2012). Social anxiety and adolescents’ friendships: The role of social withdrawal. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32, 802–823. 10.1177/0272431611426145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, & Brechman-Toussaint ML (2006). Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 834–856. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, & Phares V (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 539–558. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol.2. Separation. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brennen T (1974). Evaluation and validation regarding the national strategy for youth development. Boulder, CO: Behavioral Research Evaluation Program. [Google Scholar]

- Burk W, & Laursen B (2005). Adolescent perceptions of friendship and their associations with individual adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 156–164. 10.1080/01650250444000342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KE, & Ladd GW (2000). Connectedness and autonomy support in parent-child relationships: Links to children’s socioemotional orientation and peer relationships. Developmental Psychology, 36, 485–498. 10.1037//0012-1649.36.4.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK (2003). Perceptions of parent-child attachment, social self-efficacy, and peer relationships in middle childhood. Infant and Child Development, 12, 351–368. 10.1002/icd.316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & Russell G (1991). Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review, 11, 99–136. 10.1016/0273-2297(91)90004-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EC, Buehler C, & Fletcher AC (2012). A process model of parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence. Social Development, 21, 461–481. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00642.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Paley B (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Bonica C, & Rincon C (1999). Rejection sensitivity and adolescent romantic relationships In Furman W, Brown BB, & Feiring C (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 148–174). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epkins CC, & Heckler DR (2011). Integrating etiological models of social anxiety and depression in youth: Evidence for a cumulative interpersonal risk model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 329–376. 10.1007/s10567-011-0101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdley CA, & Day HJ (2017). Friendship in childhood and adolescence In Hojjat M & Moyer A (Eds.), The psychology of friendship (pp. 3–19). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Caruthers AS, & Dishion TJ (2012). A six-year predictive test of adolescent family relationship quality and effortful control pathways to emerging adult social and emotional health. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 565–575. 10.1037/a0028873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, & Grych JH (2013). Capturing the family context of emotion regulation: A family systems model comparison approach. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 557–578. 10.1177/0192513X12445889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Stormshak EA, Dishion TJ, & Winter CE (2012). Family relationships and parental monitoring during middle school as predictors of early adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41, 202–213. 10.1080/15374416.2012.651989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Van Ryzin MJ, Xia M, & Feinberg ME (2016). Trajectories of adolescent hostile-aggressive behavior and family climate: Longitudinal implications for young adult romantic relationship competence. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1139–1150. 10.1037/dev0000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot D, & Mayseless O (2012). Representations of mother-child attachment relationships and social-information processing of peer relationships in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32, 537–564. 10.1177/0272431611403482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J (2017). Friendship and health In Hojjat M & Moyer A (Eds.), The psychology of friendship (pp. 233–248). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HD, Lavoie JC, & Mahoney M (2001). Interparental conflict and family cohesion: Predictors of loneliness, social anxiety, and social avoidance in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 304–318. 10.1177/0743558401163004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones WH, Rose J, & Russell D (1990). Loneliness and social anxiety In Leitenberg H (Ed.), Handbook of social and evaluation anxiety (pp. 247–266). New York, NY: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Contreras JM, & Neal-Barnett AM (Eds.). (2000). Family and peers: Linking two social worlds. Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Knappe S, Beesdo-Baum K, Fehm L, Lieb R, & Wittchen H-U (2012). Characterizing the association between parenting and adolescent social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 608–616. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappe S, Beesdo-Baum K, Fehm L, Stein MB, Lieb R, & Wittchen H-U (2011). Social fear and social phobia types among community youth: Differential clinical features and vulnerability factors. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 111–120. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappe S, Lieb R, Beesdo K, Fehm L, Ping Low NC, Gloster AT, & Wittchen H-U (2009). The role of parental psychopathology and family environment for social phobia in the first three decades of life. Depression and Anxiety, 26, 363–370. 10.1002/da.20527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappe S, Sasagawa S, & Creswell C (2015). Developmental epidemiology of social anxiety and social phobia in adolescents In Ranta K, La Greca AM, Garcia-Lopez LJ, & Marttunen M (Eds.), Social anxiety and phobia in adolescents: Development, manifestation and intervention strategies (pp. 39–70). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, & Lopez N (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents : Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 83–94. 10.1023/A:1022684520514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, & Ranta K (2015). Developmental transitions in adolescence and their implications for social anxiety In Ranta K, La Greca AM, Garcia-Lopez LJ, & Marttunen M (Eds.), Social anxiety and phobia in adolescents: Development, manifestation and intervention strategies (pp. 95–117). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM, & Crouter AC (2012). Parent-child shared time from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 83, 2089–2103. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01826.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, & Lewis C (2010). The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families In Lamb ME (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed., pp. 94–153). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy MS, Guerra NG, & Toro RI (2012). Positive parenting, family cohesion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 252–260. 10.1037/a0019407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, & Lamb ME (2003). Fathers’ influences on children’s development: The evidence from two-parent families. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18, 211–228. 10.1007/BF03173485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Downey G, Bonica C, & Paltin I (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 481–506. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majdandžić M, de Vente W, Feinberg ME, Aktar E, & Bögels SM (2012). Bidirectional associations between coparenting relations and family member anxiety: A review and conceptual model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 28–42. 10.1007/s10567-011-0103-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston EG, Hare A, & Allen JP (2010). Rejection sensitivity in late adolescence: Social and emotional sequelae. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 959–982. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00675.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56, 289–302. 10.2307/1129720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos BS, & Moos RH (1994). Family Environment Scale manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nair MKC, Russell PSS, Subramaniam VS, Nazeema S, Chembagam N, Russell S, … Charles H (2013). ADad 8: School phobia and anxiety disorders among adolescents in a rural community population in India. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 80, 171–174. 10.1007/s12098-013-1208-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, & Bagwell CL (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 306–347. 10.1037//0033-2909.117.2.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Nielson MG, & Day RD (2016). The role of parental warmth and hostility on adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward multiple targets. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 331–340. 10.1037/fam0000157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, & Ladd GW (Eds.). (1992). Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, & Asher SR (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, & Borge AIH (2007). The timing of middle-childhood peer rejection and friendship: Linking early behavior to early-adolescent adjustment. Child Development, 78, 1037–1051. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KG, Cunningham TJ, & Young MB (1997). Attachment to parents, social competence, and emotional well-being: A comparison of Black and White late adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44, 89–101. 10.1037/0022-0167.44.1.89 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP (1986). The warmth dimension. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP (2004). The parental “acceptance-rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist, 59, 830–840. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, & Britner PA (2002). Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research, 36, 16–47. 10.1177/106939710203600102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph J, & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2014). Parent relationships and adolescents’ depression and social anxiety: Indirect associations via emotional sensitivity to rejection threat. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 110–121. 10.1111/ajpy.12042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ (Ed.). (2009). The transactional model of development: how children and contexts shape each other. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz B, Stutz M, & Ledermann T (2012). Perceived interparental conflict and early adolescents? Friendships: The role of attachment security and emotion regulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1240–1252. 10.1007/s10964-012-9769-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Greenberg M, Bierman K, & Redmond C (2004). PROSPER community–university partnership model for public education systems: Capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science, 5, 31–39. 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013979.52796.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Tu KM, Erath SA, Pettit GS, & El-Sheikh M (2014). Physiological reactivity moderates the association between parental directing and young adolescent friendship adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2644–2653. 10.1037/a0038263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Abwender DA, Ewell KK, & Beery SH (1992). Social anxiety and peer relationships in early adolescence: A prospective analysis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 189–196. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2102_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrip AM, Malcolm KT, & Jensen-Campbell LA (2008). With a little help from your friends: The importance of high-quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development, 17, 832–852. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00476.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SL, Huston L, Egeland B, & Sroufe LA (1997). Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 637–644. 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg MP, Drewes MJ, Goedhart AW, Siebelink BM, & Treffers PDA (2004). A developmental analysis of self-reported fears in late childhood through mid-adolescence: social-evaluative fears on the rise? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 481–495. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF (2006). III. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 71, 42–64. 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.00404.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Stein MB, & Kessler RC (1999). Social fears and social phobia in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine, 29, S0033291798008174 10.1017/S0033291798008174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong QJJ, & Rapee RM (2015). The developmental psychopathology of social anxiety and phobia in adolescents In Ranta K, La Greca AM, Garcia-Lopez LJ, & Marttunen M (Eds.), Social anxiety and phobia in adolescents: Development, manifestation and intervention strategies (pp. 11–37). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]