Abstract

Large numbers of U.S. physicians and medical trainees engage in hands-on clinical global health experiences abroad, where they gain skills working across cultures with limited resources. Increasingly, these experiences are becoming bidirectional, with providers from low- and middle-income countries traveling to experience health care in the United States, yet the same hands-on experiences afforded stateside physicians are rarely available for foreign medical graduates or postgraduate trainees when they arrive. These physicians are typically limited to observership experiences where they cannot interact with patients in most U.S. institutions. In this article, the authors discuss this inequity in global medical education, highlighting the shortcomings of the observership training model and the legal and regulatory barriers prohibiting foreign physicians from engaging in short-term clinical training experiences. They provide concrete recommendations on regulatory modifications that would allow meaningful short-term clinical training experiences for foreign medical graduates, including the creation of a new visa category, the designation of a specific temporary licensure category by state medical boards, and guidance for U.S. host institutions supporting such experiences. By proposing this framework, the authors hope to improve equity in global health partnerships via improved access to meaningful and productive educational experiences, particularly for foreign medical graduates with commitment to using their new knowledge and training upon return to their home countries.

Foreign medical graduates (FMGs)—here referring to non-U.S. citizens receiving their basic medical degree outside the United States or Canada—who desire formal clinical training in the United States have a clear pathway through residencies certified by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). FMGs constitute approximately 16% of the U.S. physician workforce, providing critical human resources for our health care system.1,2 Ironically, FMGs who want advanced, short-term clinical training from U.S. institutions so that they can provide better care in their home countries typically can only access “observership” programs while in the United States, so named because such programs allow nothing beyond observation in clinical settings.3 In contrast, increasing numbers of U.S. medical trainees and physicians are traveling to resource-limited settings where they have substantial clinical latitude and minimal regulatory constraints.4,5 Despite a growing call for increased equity within these short-term exchanges,6 the flow of learners remains largely unidirectional, with a disproportionate number of U.S. physicians and trainees visiting partner sites abroad, often with full engagement in clinical care. Although there are some successful models for creating short-term experiences for FMGs at U.S. medical centers,7,8 there are institutional and legal barriers that make it challenging for these learners to have meaningful clinical experiences.

In this article, we address the current imbalance in global health training opportunities, focusing on hosting FMGs for short-term clinical training experiences in the United States. We systematically explore regulatory barriers, discuss the applicable laws, and offer recommendations for the revision of visa categories and licensing laws to improve the educational impact and equity of international partnerships that offer U.S.-based learning opportunities for foreign physicians. We advocate for a legal framework that would allow such FMGs to come to the United States for short-term, structured medical training programs permitting hands-on clinical education, thereby improving their ability to build capacity within their respective health care systems.

Arguments for Equitable Exchanges in Health Education

Before addressing the logistics of providing short-term clinical training for FMGs, it is important to review why U.S. institutions should support equity in their international partnerships.

Equity in professional health education supports international goals for health

Improving care and increasing access to best practices internationally will decrease health disparities.9,10 The world’s richest and poorest countries have a 100-fold gap in national income and a 1,000-fold gap in per capita health care expenditures; health care education can and should help reduce disparities in outcomes.11 The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals seek to address these disparities and call on all nations to be part of the solution. U.S.-based institutions can respond to this call by increasing access to pertinent and high-quality training for foreign-trained and employed physicians who can return home with new or refined skills.10 When carefully designed, these exchanges can also protect against “brain drain” by specifically targeting FMGs who have already begun local careers; embedding the out-of-country training experiences as part of the framework of the home program; and offering ongoing opportunities for bidirectional faculty exchanges, including mentorship, reentry funding, and research partnerships.7,12–15

Equitable exchanges improve the long-term stability of global health training

Bidirectional learning provides mutual gains for U.S. and foreign clinicians, institutions, and patients. Clinicians from both settings stand to benefit from working in new settings with different delivery models, epidemiology, and cultural norms, with U.S. clinicians building clinical abilities in limited-resource care while FMGs learn advanced techniques that may be less prevalent in their setting.10,11,16 These benefits can be negated if clinicians pick up inappropriate practices during exchanges, such as an FMG increasing unnecessary medical testing after a rotation in the United States or a U.S. clinician reducing their use of medically indicated testing after a rotation abroad. Accordingly, attention does have to be paid to the learning objectives in these exchanges, and these concerns should be openly discussed by all parties. Equitable, bidirectional exchange strengthens partnerships and enriches scholarly interactions.11,17 Such collaborations were seen as beneficial by 80% of North American academic partners and over 75% of international institutional partners in a 2015 survey.18

Because disease knows no borders, strong health systems are needed everywhere

Ebola, Zika, influenza, HIV, and other infectious outbreaks make this argument clear, as does the platform of the Global Health Security Agenda, to which the United States belongs.19 Training physicians from both high- and low-resource areas builds local capacity for improving health and economic stability, and this potentially translates to improved worldwide health and economic security.11,20 Although related discussion often focuses on reducing epidemic threats originating in limited-resource areas, patients and systems in resource-rich areas can also benefit directly from clinicians with improved physical exam abilities, confidence in clinical reasoning, and greater knowledge of high-value, low-cost care.

Observerships: Limited Education

Working in tandem, current state and federal laws generally prohibit short-term clinical FMG training programs that allow patient contact. Given these barriers, motivated host institutions have created “observership” programs, which the American Medical Association describes in a guidance document as “not intended to fill gaps in clinical knowledge or training” but only meant to “familiarize and acculturate an international medical graduate to the practice of medicine in an American clinical setting.”3 Although program design is flexible, observerships are short-term and do not allow

Taking a patient history and/or doing a patient exam;

Administering medications or writing orders;

Documenting in the medical record;

Dictating lab reports or operative notes; or

Obtaining patient consent for surgery or research.

Learning during an observership typically takes place through participating in didactics and observing the delivery of health care. Although evaluations of these programs have revealed a high degree of FMG satisfaction,21,22 they cannot substitute for the hands-on clinical training that is the foundation of medical education.23–25 Outside of the United States, other high-income countries (e.g., Canada and the United Kingdom) have a more measured approach allowing graded responsibilities for visiting FMG trainees, including those in the surgical subspecialties where a hands-on component is critical for learning.26,27

Visa, State Licensure, and Liability Barriers to Equitable Educational Exchanges

Visa issues

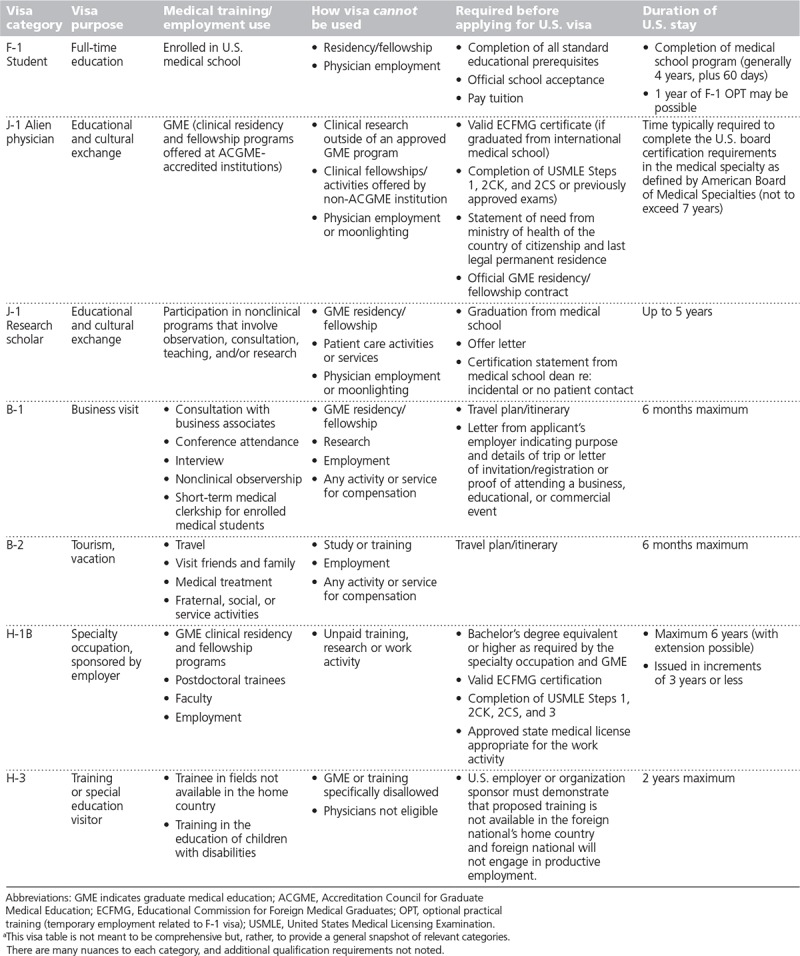

The U.S. State Department supports several visa categories for nonimmigrant travelers who come to the United States for medical training, but none of these existing categories permits a short-term clinical training visit. Table 1 outlines the individual visas potentially available for international physicians or trainees. Simply put, there is no existing visa category allowing an FMG to enter the United States for a short-term clinical program that allows patient contact.

Table 1.

U.S. Nonimmigrant Visas Used for Medical Education by Foreign Medical Students, Medical Graduates, and Practicing Physiciansa,34,35

State medical board licensure

The equitable short-term clinical training programs we envision would allow FMGs to engage in the “practice of medicine,” which, although defined by each individual state, generally means “to engage, with or without compensation, in medical diagnosis, healing, treatment, or surgery.”28 U.S. states and territories regulate physicians who practice medicine within their borders through medical boards that license and discipline physicians.

Within ACGME-accredited residency programs, both U.S.-trained physicians and FMGs are licensed by their state medical boards to practice within the confines of the program, supervised by faculty, and subject to medical board regulation and oversight.29 If they have completed training outside of the United States, however, FMGs face a steep barrier to practice in the United States. For FMGs to obtain full medical licensure to practice medicine, states generally require graduation from an accredited U.S. medical school or Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG)-verified credentials, completion of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) series, at least one year of postgraduate training as an intern or first-year resident, a background check, and knowledge of oral and written English.30 Therefore, at the current time, obtaining state medical licensure is unrealistic for FMGs participating in short-term clinical visits.

Fifteen state medical boards have authorizing language that would allow an FMG to apply for, or obtain, some form of “temporary” or “visiting/courtesy” license to practice medicine without having to meet the requirements for a full license, but only Louisiana, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Ohio have licensure categories specifically designed to allow FMGs to practice medicine in short-term clinical training programs. As a model example, in 2012, the Ohio legislature created a Visiting Clinical Professional Development Certificate category that allows non-U.S. physicians to interact directly with patients for up to one year under close supervision by a U.S. physician.31 This effort was championed by a number of academic medical centers in Ohio to allow visiting physicians the opportunity to learn advanced treatments and technologies, thereby building capacity in their home countries upon their return. Allowable supervised activities include taking medical histories, conducting physician examinations, performing surgical procedures, administering anesthesia, and doing radiologic studies. Physicians in this category cannot write orders or prescribe medicine, bill for services, take a position in a residency program, have training count toward U.S. graduate medical education, or remain in Ohio to practice medicine after completing the program.

The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) encourages state boards to “address the unique and sometimes novel issues that arise in their states” by creating special and/or temporary licenses for such purposes as traveling sports team physicians, patient care during natural or manmade disasters, and special practice such as an “institutional physician.”32 The latter category, adopted by about 50% of state medical boards, is relevant because it allows FMGs to practice in a state without meeting the USMLE testing and other requirements required for full state licensure. However, as defined by the FSMB, this category typically requires the applicant to have a faculty position and is therefore designed for teaching rather than learning.

The Ohio Visiting Clinical Professional Development Certificate and a sample of other limited licensure categories created by states are set forth in Table 2. These examples demonstrate the authority and ability of state medical boards to create licensure categories to meet new circumstances if the board is convinced that patient safety will be maintained by those practicing in the new category.

Table 2.

Examples of Special Licensure Categories That Apply to Foreign Medical Graduates

Professional liability insurance

Allowing FMGs to engage in clinical care during a short-term training program raises the specter of medical malpractice liability and the question of who is responsible for the clinical practice of an FMG participant. As a preliminary point, we were unable to find any legal case or settlement related to medical malpractice by an FMG in a short-term training program, either clinical or in observation only.* Second, professional liability insurance coverage for short-term clinical visitors is readily available on the commercial market, via the categories used for locum tenens and similar short-term physician employees. Although ideally university or affiliated hospitals would extend their professional liability insurance programs to cover FMGs for these experiences, commercial policies provide a feasible approach for the moment, albeit at some cost to either the participant or the host institution.

Recommendations: Turning Toward Equity

To promote equity in medical training opportunities and support meaningful health care capacity development worldwide, specific legal and regulatory changes must be made at the federal and state levels to allow U.S. universities and affiliated hospitals to create effective short-term clinical training programs for non-U.S. learners. Immigration and medical licensure laws are interdependent (i.e., getting a state license depends on visa status, and getting a visa depends on licensure status) and therefore impose what we feel are presently the most significant barriers. Accordingly, we recommend that state medical boards create a temporary licensure category that allows full participation for FMGs in short-term clinical training activities, under guidelines outlined in Box 1.

Box 1.

Recommended Temporary Licensing Statute for Short-Term Clinical Training of FMGs

The licensee will train under close supervision by a U.S. physician. In this context “close supervision” means the same degree of supervision required for residents and fellows in ACGME-accredited programs.

-

The licensee may interact directly with patients, including:

a. taking medical histories

b. conducting physician examinations

c. performing surgical procedures

d. administering anesthesia

e. reading radiologic studies

-

The licensee may not:

a. assume independent responsibility for patient care

b. write medical orders

c. prescribe medicine

d. bill for services

-

Temporary licenses should be granted with the explicit understanding by the applicant that the license cannot be used to:

a. take a position in a residency program

b. count toward U.S. graduate medical education requirements

c. remain in the state to practice medicine beyond the scope of the training program

Licenses should be issued for up to one year

Although the FMGs will not assume responsibility for patients, we additionally recommend that state medical boards request the following information from applicants:

Written acceptance into a clinical professional development or short-term clinical training program

A medical degree from an institution recognized in the International Medical Education Directory

Evidence that credentials were verified by the hosting institution or ECFMG

Evidence that the applicant has an unrestricted license to practice medicine in the applicant’s country of origin or country of practice

Evidence that the applicant has no significant criminal record and no significant disciplinary actions by former training institutions or employers

Abbreviations: FMG indicates foreign medical graduate; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; ECFMG, Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates.

To overcome the reservations of state licensing bodies and professional liability insurers, it will be critical that the host institution officials ensure that clinical program participants are closely supervised to limit potential negative effects on patients or other learners. In this context, “close supervision” means the same degree of supervision required for residents in an ACGME-accredited program.

We recommend that the Department of State should authorize a new J-1 visa category that allows FMGs to enter the United States for short-term clinical training. In 2014, the ECFMG convened a working group, including representation from the ACGME, that addressed many of the visa issues we discuss in this article and also concluded that a new visa category was appropriate. The ECFMG could be the sponsoring agency and verify the applicant’s credentials, or this could be undertaken by the host institution. The visa program should require that short-term clinical activity will not be creditable toward the requirements of an ACGME-accredited program and/or certification by a member board of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Because one of the top priorities of medical training equity initiatives is limiting brain drain, visa applicants should assert (via personal statement or other instrument) that they understand the requirement that they return to their home country upon completion of the short-term clinical training activity.

According to its unpublished 2014 report, the ECFMG working group suggested requiring that applicants for the new visa category present evidence “of an approved license, permit or other authorization from the appropriate U.S. state medical licensing board verifying the applicant’s eligibility to participate in the proposed short-term clinical training activity.”33 This language is a signal that the ECFMG understands the importance of resolving the state licensure issue as a precondition for the new visa category to function as intended. Many state medical boards will not issue a license until a visa is obtained. We support this language, particularly the “other authorization” clause that would allow state licensing boards to provide letters to the ECFMG stating that a license will be forthcoming once the applicant has a visa.

Finally, we recommend that U.S. host institutions should have memoranda of understanding with the partnering institutions in the FMGs’ home countries. Although the ECFMG recommended a limit of six months for training programs, we suggest a one-year limit, as a longer period may be necessary to achieve specific learning objectives, especially in procedural or research work, whereas shorter periods may suffice for focused education on systems or educational approaches. A longer period also respects the time necessary for FMGs to adapt to a new clinical setting, as onboarding will take longer if FMGs are actively involved in clinical care.

Concluding Remarks

It is time for U.S. institutions to reevaluate the current global health education and partnership model, which has long been focused on providing meaningful clinical experiences to American trainees abroad, and to provide more equitable educational opportunities for FMGs determined to improve the health of their home countries. This approach strengthens international partnerships, builds international clinical capacity, works toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals, strengthens health systems, and ultimately improves global health and economic security. These goals cannot be met until legal and regulatory barriers to short-term clinical training and professional development programs for international physicians are addressed. In this era of geopolitical tension surrounding immigration policy, moving forward with the proposals in this paper will require significant political backing at the national and state levels, combined with evidence to support the underlying goals of the proposals. Therefore, we recommend that global health organizations and universities with existing international partnerships consider conducting feasibility studies, focus groups, and surveys of university international student and scholar offices to gather data surrounding the proposals. As a next step, the Consortium of Universities for Global Health intends to convene a meeting of various stakeholders, including university and nongovernmental global health organizations from high-, middle-, and low-income countries; state medical board representatives; leaders from national physician organizations; and medical education leaders, hopefully including representation from the Association of American Medical Colleges and the ACGME. This group will develop both national- and state-level advocacy plans to enact the proposals in this article. Of note, we believe that the various elements of this proposal can be implemented in parallel and to some degree piecemeal. Although the greatest benefit would be to enact all of the changes, institution- and state-level advocacy as seen in Ohio can lead to local progress. We welcome further data on these and related proposals, and look forward to a national dialogue that moves us toward equity.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Secretariat and Education Committee of the Consortium of Universities for Global Health as well as research assistant Hassan Sheikh (University of Maryland Carey School of Law 2018) for their support.

Search via the Westlaw online legal research platform conducted on September 1, 2016: “Jury Verdicts & Settlements” and “Health Law” filters using search terms “international medical graduate,” “foreign medical graduate,” “medical observership,” and “medical externship”; FMGs in ACGME-accredited programs were not included in the search parameters.

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Center for Workforce Studies. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2015 state physician workforce data book. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2015StateDataBook%20(revised).pdf. Published November 2015. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 2.Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. 2015 annual report. https://www.ecfmg.org/resources/ECFMG-2015-annual-report.pdf. Published April 16, 2016. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 3.American Medical Association. Observership program guidelines and evaluation forms. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/img/observership-program-guidelines_1.doc. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 4.St. Clair NE, Pitt MB, Bakeera-Kitaka S, et al. Global health: Preparation for working in resource-limited settings. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20163783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melby MK, Loh LC, Evert J, Prater C, Lin H, Khan OA. Beyond medical “missions” to impact-driven short-term experiences in global health (STEGHs): Ethical principles to optimize community benefit and learner experience. Acad Med. 2016;91:633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arora G, Russ C, Batra M, Butteris SM, Watts J, Pitt MB. Bidirectional exchange in global health: Moving toward true global health partnership. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabin TL, Mayanja-Kizza H, Rastegar A. Medical education capacity-building partnerships for health care systems development. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18:710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitt MB, Gladding SP, Majinge CR, Butteris SM. Making global health rotations a two-way street: A model for hosting international residents. Glob Pediatr Health. 2016;3:2333794X16630671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ackerly DC, Udayakumar K, Taber R, Merson MH, Dzau VJ. Perspective: Global medicine: Opportunities and challenges for academic health science systems. Acad Med. 2011;86:1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer PE, Rhatigan JJ. Embracing medical education’s global mission. Acad Med. 2016;91:1592–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey N, Mandeville KL, Rhodes T, Mipando M, Muula AS. Postgraduate career intentions of medical students and recent graduates in Malawi: A qualitative interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umoren RA, James JE, Litzelman DK. Evidence of reciprocity in reports on international partnerships. Educ Res Int. 2012;10:603270. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert TJ, Fassier T, Chhuoy M, et al. Bolstering medical education to enhance critical care capacity in Cambodia. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kupfer L, Hofman K, Jarawan R, McDermott J, Bridbord K. Strategies to discourage brain drain. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:616–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaGrone LN, Isquith-Dicker LN, Huaman Egoavil E, et al. Surgeons’ and trauma care physicians’ perception of the impact of the globalization of medical education on quality of care in Lima, Peru. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz JI, Dunkle A, Akiteng AR, et al. Towards reframing health service delivery in Uganda: The Uganda Initiative for Integrated Management of Non-Communicable Diseases. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:26537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muir JA, Farley J, Osterman A, et al. Global Health Programs and Partnerships: Evidence of Mutual Benefit and Equity—A Report of the CSIS Global Health Policy Center and the University of Washington Global Health START Center, in Collaboration With the Consortium of Universities for Global Health. 2016. Lanam, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160315_Muir_GlobalHealthPrograms_Web.pdf. Published March 2016. Accessed September 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The global health security agenda. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/ghsagenda.htm. Updated January 27, 2016. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 20.Kalra S, Kelkar D, Galwankar SC, et al. The emergence of Ebola as a global health security threat: From “lessons learned” to coordinated multilateral containment efforts. J Glob Infect Dis. 2014;6:164–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umoren RA, Einterz RM, Litzelman DK, Pettigrew RK, Ayaya SO, Liechty EA. Fostering reciprocity in global health partnerships through a structured, hands-on experience for visiting postgraduate medical trainees. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodnar BE, Claassen CW, Solomon J, Mayanja-Kizza H, Rastegar A. The effect of a bidirectional exchange on faculty and institutional development in a global health collaboration. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu PM, Park EE, Rabin TL, et al. Impact of global health electives on U.S. medical residents: A systematic review. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84:692–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hau DK, Dipace JI, Peck RN, Johnson WD., Jr Global health training during residency: The Weill Cornell Tanzania experience. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:421–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shull H, Tymchuk C, Grogan T, Hamilton J, Friedman J, Hoffman RM. Evaluation of the UCLA Department of Medicine Malawi global health clinical elective: Lessons from the first five years. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:876–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta. Medical practice observation/experience. http://cpsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Medical-Practice-Observation-Experience.pdf. Revised August 2011. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 27.Royal Colleges of Obstetricians & Gynaeologists. Medical Training Initiative (MTI) scheme. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/careers-training/working-in-britain-for-non-uk-doctors/medical-training-initiative-mti-scheme. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 28.Maryland Department of Human Resources. Annotated Code of Maryland. Health Occupations, § 14–101(n). https://dhr.maryland.gov/documents/Licensing-and-Monitoring/Maryland%20Law%20Articles/RCC/HEALTH%20OCCUPATIONS%20Title%2014%20Physicians.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 29.Federation of State Medical Boards. Position in support of postgraduate training and licensure standards. https://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/1998_grpol_Postgraduate_Training_Licensure.pdf. Adopted 1998. Accessed December 29, 2017.

- 30.Federation of State Medical Boards. State-specific requirements for initial medical licensure. https://www.fsmb.org/step-3/state-licensure. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 31.47 Ohio Revised Code Ann. § 4731.298. Visiting clinical professional development certificate. http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/4731.298v1. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 32.Federation of State Medical Boards. Report of the FSMB Workgroup on Innovations in State Based Licensure. http://www.fsmb.org/globalassets/advocacy/policies/innovations-in-state-based-licensure.pdf. Updated April 2014. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 33.Rowthorn VM. Executive director, University of Maryland Center for Global Education Initiatives. Unpublished document in possession of the authors.

References cited in tables only

- 34.U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Immigration and Nationality Act. § 101. 8 U.S.C. 1101 a, 1–15. (1952). https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/SLB/HTML/SLB/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-29/0-0-0-101.html. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 35.U.S. Department of State. J-1 Visa. Exchange Visitor Program. Professor and research scholar programs. https://j1visa.state.gov/programs. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 36.Medical Board of California. Special Faculty Permit under Section 2168 of the Business and Professions Code. http://www.mbc.ca.gov/Applicants/Physicians_and_Surgeons/Special_Faculty_Permit.aspx. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 37.Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code §2111. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=BPC&division=2.&title=&part=&chapter=5.&article=3. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 38.The Florida Legislature. The 2018 Florida Statutes. Regulation of Professions and Occupations. Medical Practice. § 458.3135 (2017). http://www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=0400-0499/0458/Sections/0458.3135.html. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 39.Lousiana State Board of Medical Commissioners. Application and instructions for initial licensure—Short-term IMG. http://www.lsbme.la.gov/content/application-instructions-initial-licensure-short-term-img. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 40.Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine. Temporary license application instructions. http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/borim/kits/temporary-kit.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 41.Licensing and Regulatory Affairs. Bureau of Professional Licensing. Michigan medical doctor (MD) licensing guide. http://www.michigan.gov/documents/lara/Medicine_517648_7.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 42.Faculty/special purpose applications for physicians. https://www.ncmedboard.org/licensure/licensing/physicians/special-purpose-application. Accessed September 18, 2018.