Abstract

The Mucorales fungi—formerly classified as the zygomycetes—are environmentally ubiquitous fungi, but generally rare causes of clinical infections. In the immunocompromised host, however, they can cause invasive, rapidly spreading infections that confer a high risk of morbidity and mortality, often despite surgical and antifungal therapy. Patients with extensive burn injuries are particularly susceptible to skin and soft-tissue infections with these organisms. Here, we present a case of Lichtheimia infection in a patient with extensive full-thickness burns that required significant and repeated surgical debridement successfully treated with isavuconazole and adjunctive topical amphotericin B washes. We also review the available literature on contemporary antifungal treatment for Lichtheimia species and related Muco- rales fungi.

Keywords: Lichtheimia, Isavuconazole, Burn, Absidia, Mucorales

Introduction/Case

A 63-year-old man with a history of type-2 diabetes mellitus and a remote myocardial infarction was airlifted to our regional burn center following a workplace explosion that produced full-thickness burns of approximately 47% of his total body surface, predominantly involving his head, torso and upper extremities. On arrival, he was intubated, stabilized, and transferred to the operating room for escharotomy (emergent surgical decompression of circumferential burns to prevent compartment syndrome) of his extensively burned left arm.

On hospital day (HD) 3, burn surgeons performed debridement of his chest and placement of an Integra™ bilayer burn dressing, which consists of an engineered collagen and glycosaminoglycan matrix that facilitates re-growth of the dermal layer and a temporary silicone outer layer that provides temporary coverage prior to epidermal skin grafting. On HD 6, he underwent debridement and Integra coverage of his arms; on HD 9, debridement of his face and splitthickness dermal allografting of his flanks and back were performed. During this time, he developed intermittent fevers and rising white blood cell (WBC) count. Vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobac-tam were administered empirically for presumed bacterial pneumonia due to associated increased secretions; bronchoalveolar lavage grew Streptococcus pneumonia so antibiotics were narrowed to ceftriaxone to complete a 10-day course.

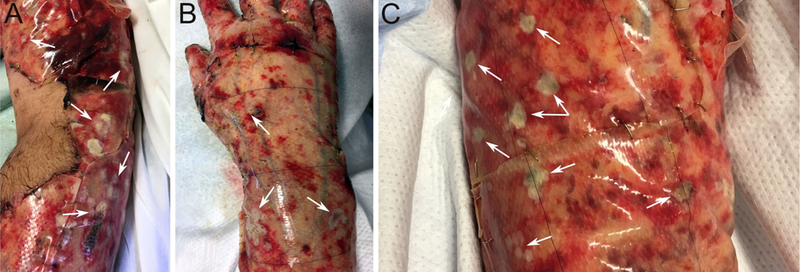

On HD 10, the surgical team noted a small white plaque concerning for a fungal infection on his left arm. Fungal cultures were obtained, and posaconazole was initiated. He improved over the following days, with removal of flank allografts on HD 12, extubation, and discontinuation of posaconazole on HD 13. However, 4 days after tissue samples were obtained, and a culture positive for Lichtheimia sp. was reported on HD14, prompting re-initiation of posaconazole. Over the following days, his WBC count rose daily, and he developed respiratory failure, requiring reintubation and ultimately tracheostomy. On HD 20, multiple new white plaques were noted on the Integra covering the bilateral upper extremities (Fig. 1) and torso. The Integra dressing was removed from his chest and flanks and autologous split-thickness skin grafting was performed. While the majority of the white plaques were removed when the Integra was removed, there were small residual white plaques adherent in the underlying tissue of the abdomen. Cultures of the Integra from multiple sites (both upper extremities, chest, abdomen, and flanks) all rapidly grew Lichtheimia sp. Due to the spread of Lichtheimia, while the patient was receiving posaconazole, a change to systemic amphotericin B was considered, but rejected due to declining urine output and a creatinine steadily rising to 3.1 mg/dL by HD 22. In lieu of systemic amphotericin B, he was switched to intravenous (IV) isavuconazole with adjunctive topical amphotericin B washes.

Fig. 1.

Dressing change (HD 20) prior to removal of the Integra engineered dermal substitute. Note the presence of multiple small white plaques (white arrows) on the patient’s right arm (a), right hand (b), and a magnified portion of the left arm (c)

Over subsequent debridements, there was a decreased burden of macroscopic fungal disease and fungal organism recovery from cultures; the last culture positive for Lichtheimia was obtained on HD 48, with none isolated thereafter. The patient completed a total of 6 weeks of isavuconazole therapy through HD 62, and 13 days of topical amphotericin B washes through HD 35. While the patient required ongoing skin grafting with revisions, there was no further detectable recurrence of Lichtheimia sp. He was discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility after a 119-day hospital stay.

Fungal Infections in Severe Burn Patients

Patients with extensive burn injuries are at markedly increased risk of localized and systemic infections due to loss of skin barrier function need for multiple procedures, and dependence on indwelling catheters [1]. The combination of loss of cutaneous barrier and exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics targeting bacterial infection puts these patients at particular risk of invasive fungal infections. Among the fungal etiologies, Candida remains the most common overall, but members of the Mucorales order are becoming more frequent [1, 2]. Formerly classified in the taxonomi-cally vague “zygomycetes” group, the Mucorales are environmental fungi that can be opportunistic pathogens in patients with impaired host defenses, including patients with diabetes, as was the case for our patient. These infections are notable for their rapid clinical progression and invasive nature, with endovascular ingrowth leading to rapid systemic spread and colonization of distant sites [3–5]. While cutaneous forms of Mucorales infection generally carry a more favorable prognosis than other forms of disease, such as invasive pulmonary or widely disseminated infection [6], reported mortality rates in burn patients are often more similar to those with invasive disease [7]. The extent of invasive disease in burn patients may be underappreciated, because biopsies are not avoided due to risk of compromising the integrity of the recovering skin barrier [1].

Treatment poses distinct clinical challenges and is largely extrapolated from management of similar fungal infections in patients with hematological malignancies and trauma-associated cutaneous infections [8] due to the paucity burn-specific data on optimal management. Aggressive, early, and often repeated surgical debridement remains a cornerstone of management for Mucorales infections, irrespective of site of infection [3–5]. Prompt antifungal therapy is also critical to successful resolution of invasive infections [6] and both surgical and systemic antifungal agents are typically employed jointly in burn-associated Mucorales infections. Unfortunately, there are relatively few demonstrably effective antifungal agents. The most extensively studied of these is amphotericin B, a polyene antifungal isolated from Streptomyces nodosus in 1955, but its use is often limited by significant toxicities. Newer azole drugs including posaconazole and isavuconazole have shown promise, primarily in patients with hematological malignancies, but have not been studied specifically in patients with burns. Although these newer therapeutic agents are mechanistically promising in vitro and there is some evidence from treated patients showing distribution into muscle and fat [9], there are many unanswered questions related to use in burn patients, particularly regarding the ability to obtain therapeutic drug levels in burned cutaneous tissues, and the unique dosing needs of patients with dramatically increased metabolic drive and impaired physiologic handling of fluid [1]. Fluconazole is one of the best-studied azoles with respect to pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties and exhibits concentration-and time-dependent antifungal activity with a prolonged post-antifungal effect. The best predictor of fungicidal activity has been shown to be the ratio of free drug area under the concentrationtime curve from 0 to 24 h to minimum inhibitory concentration (fAUC0–24/MIC) [10]. Sinnollareddy et al. demonstrated substantial variability in fraction of critically ill patients reaching this target with standard dosing regimens, and in burn patients, Santos et al.[11]. demonstrated a need for dose adjustment based on plasma drug levels in the majority of patients. These data highlight the need for dedicated PK/PD studies of isavuconazole in the burn patient population.

The Genus Lichtheimia

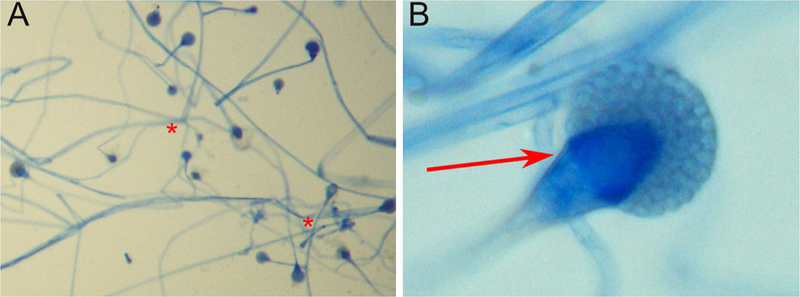

Formerly categorized within the genus Absidia, fungi in the genus Lichtheimia, along with Mucor, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, and several other former zygomycetes, have been recently taxonomically assigned to the fungal order Mucorales [12]. Identification of Muco-rales to the genus level by morphology alone is complex, but can be done by experienced technologists. Definitive identification to the level of a particular species is more challenging and generally requires extensive specialized training and experience. Lichtheimia species cannot be reliably distinguished from other Mucorales in tissue by H & E staining or even using fungal-specific histochemical labeling (i.e. GMS or PAS) [13]. With clinical isolates, the macroscopic appearance of Lichtheimia spp is also highly similar to that of the other Mucorales, characterized by fast-growing, abundant, and fluffy mycelium on standard fungal media (i.e., potato dextrose agar, Sabouraud, etc.). The mycelium is initially white but turns from grey to brown as the culture ages. Microscopically, the sporangiophores are highly branched, typically unitary, or arising from small stolon-based corymbs (Fig. 2a). Rhizoids may be present, but are often difficult to visualize. The sporangia contain multiple spores that are small and range from pyriform (pear-shaped) to spherical. Col-umellae are ellipsoidal or occasionally hemispherical. The apophyses are strikingly conical (Fig. 2b; arrow), with smooth, hyaline sporangiospores [14]. Dissolution of the sporangial wall leaves a characteristic collarette attached to the columella which aids in differentiation from other Mucorales.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic features of the patient’s Lichtheimia spp isolate. Note the extensive branching from the stolons (A; red stars) and the distinctive conical apophysis characteristic of this genus (B; red arrow)

While species-level identifications based on morphology alone have been quite challenging historically, such identifications may provide important clinical information, affecting the choice of therapeutic options or providing prognostic value for patients [15]. While Lichtheimia spp. were previously known primarily for their role in plant decay processes [12], the rapid proliferation of molecular diagnostics has clarified their role as previously under-described agents of human infection. Consequently, non-mor-phological identification techniques are of increasing importance in evaluating Mucorales infections. The most ubiquitous of these in the modern clinical microbiology laboratory is mass spectrometry. While PCR and other sequencing-based approaches can provide high sensitivity and specificity, Matrix-Associated Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry systems are faster, cheaper, require less technical expertise, and are more widely available in clinical microbiology laboratories.[16]. Existing identification databases for current MALDI-TOF platforms are easily expandable to accommodate taxonomic reassignments, as well as emerging or newly described species and thus provide the most current information to clinicians. MALDI-TOF identification has been shown to differentiate Lichtheimia isolates from other Mucorales in clinical specimens and provide a species-level identification in most cases [17]. Until recently, L. corymbifera was considered to be the only pathogenic species, but improved diagnostic tools have implicated L. ramosa and L. ornata as well, with some suggestions that previous species identifications may have been erroneous [17–19]. The rapid proliferation of molecular diagnostic techniques in clinical mycology laboratories may further implicate additional members of the genus as agents of human disease.

Several Lichtheimia species are considered to be opportunistic human pathogens. In many cases, the source of exposure is presumed to be an unspecified environmental source; however, in a few cases, a clear exposure is identified, such as a trauma patient with a soil-contaminated wound [20] or burn patient exposed to contaminated dressings [21]. We are not aware of any particular candidate exposures in this patient, or of any association specifically with the Integra dressing.

The clinical outcomes of Lichtheimia infections can be quite variable. Among immunocompromised patients, Lichtheimia infection is frequently associated with very poor clinical outcomes [4, 22–26], even in patients receiving treatment. In contrast, concomitant need for systemic therapy [20, 27]. Fewer data are available regarding the natural history and optimal treatments for burn-associated Lichtheimia. In a series of burn patients who became infected as a result of a hospital outbreak attributed to contaminated bandages, three of five infected patients died, although there are insufficient data to determine whether the infection was causative in each fatality. Kaur et al. described an otherwise healthy burn patient who survived a cutaneous infection manifesting with systemic symptoms (fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea); she received combination therapy with surgical debridement and systemic amphotericin therapy. As in our case, it is challenging to determine the relative contributions of these therapies to her clinical recovery.

Antifungal Agents Active Against Lichtheimia

Similar to other Mucorales infections, amphotericin B remains an effective first-line therapy in Lichtheimia infections [28]. The echinocandins are not effective against this genus, as Mucorales lack the β−1,3-glucan linkage in the cell wall, an observation that also explains the lack of utility of the Fungitell assay [29]. First-(itraconazole and fluconazole) and second-generation triazoles (voriconazole) are ineffective against mucormycoses in vivo. To date, only posaconazole and recently approved isavuconazole have demonstrated effectiveness against Mucorales [30].

Isavuconazole

The activity spectrum of triazoles has largely been a function of the evolving side chain (Fig. 3), which affects CYP51 (lanosterol 14α-demethylase) avidity. As a result of these side chain modifications, isavu-conazole has a broad spectrum of activity in vitro that is more similar to amphotericin B, inhibiting yeasts, dimorphic fungi, and molds [30, 31]. Consistent with this, isavuconazole was approved in 2015 by the United States Food and Drug Administration for use in both invasive aspergillosis and mucormycosis infections. Approval for the latter was based on an open-label study of 37 patients with proven or probable invasive mucormycosis [32], 21 who received it as primary treatment, 11 who received it as second-line therapy due to failure of another antifungal therapy, and five who received it as second-line therapy due to intolerance to another agent. Six-week all-cause mortality remained high (38%), but isavuconazole was statistically non-inferior to amphotericin B (41%). Notably, this approval study focused heavily on oncology patients, with 59% having a hematological malignancy and 35% having undergone bone marrow transplantation at the time of enrollment, and the primary site of fungal involvement was pulmonary in the majority of patients in this study (59%). Due to the clinical heterogeneity within the small study population, it is uncertain to what extent these findings can be applied to burn patients and thus direct study of isavuconazole in this population is needed.

Fig. 3.

Generational changes in the active site of short-chain systemic triazole drugs from first generation (fluconazole; green) to early second generation (voriconazole; blue) to late second generation (isavuconazole; orange)

Although direct clinical data in burn patients are limited, isavuconazole offers multiple theoretical benefits. Isavuconazole is administered as a prodrug (isavuconazonium sulfate), which is rapidly converted to active drug in the blood without hepatic metabolism (372 mg prodrug equals 200 mg active isavuconazole). There is a simple dosing regimen that was employed for this patient, with a loading dose (isavuconazonium 372 mg three times daily for 2 days), followed by 372 mg daily dosing [32]. There is no need for adjustments with renal impairment or mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment. Isavuconazole is available in both IV and oral formulations. The oral form is 98% bioavailable with GI absorption that is rapid and unaffected by food, unlike posaconazole.[31]. Notably, unlike both posaconazole and voriconazole, the IV formulation of isavuconazole does not contain cyclodextrin, simplifying parenteral administration and eliminating risks of accumulation in renal failure. Conveniently, switching between the IV and oral forms of isavuconazole does not require dose or timing adjustment [31].

Finally, it is important to note that the total number of isavuconazole-treated Lichtheimia spp cases reported in the literature remains limited and the range of sensitivity values (MICs) is quite variable (Table 1). As such, sensitivity testing for individual patient isolates, where available, is advised to provide more specific clinical antifungal guidance.

Table 1.

Reported in-vitro Isavuconazole activity against clinical isolates of Lichtheimia (Absidia) spp.

| Fungal species | #Of isolates (291 total) |

MIC50 | MIC90 | Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absidia/Lichtheimia corymbifera | 17 | 4 | 8 | 2–8 | [28] |

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 12 | 2a | NR | 1–4 | [20] |

| 1 | NR | 1–2 | |||

| Lichtheimia ramosa | 4 | 2a | NR | 0.5–4 | [20] |

| 1 | NR | 0.5–2 | |||

| Lichtheimia ramosa | 7 | 4a | 8a | 1–8 | [29] |

| 8b | 8b | 2–8 | |||

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 6 | 2a | 8a | 2–8 | [29] |

| 8b | 8b | 1–8 | |||

| Absidia/Lichtheimia | 8 | NR | 8 | 4– > 8 | [30] |

| Absidia/Lichtheimia | 6 | 16 | NR | 0.25– > 32 | [31] |

| Absidia/Lichtheimiac | [32] | ||||

| 8 | NR | NR | 4–8 | ||

| 17 | 4 | 8 | 2–8 | ||

| 6 | NR | NR | 1–16 | ||

| 5 | NR | NR | 0.06–0.12 | ||

| 17 | 1 | 2 | 0.25–8 | ||

| 20 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.03–2 | ||

| 1 | NR | NR | 0.5 | ||

| 6 | NR | NR | 1 | ||

| 6 | 1 | 8 | 0.03–16 | ||

| Lichtheimia ramosa | 3 | NR | NR | 2–8 | [33] |

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 136 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.06–4 | [34] |

Susceptibility determined with EUCAST standards

Susceptibility determined with CLSI standards

Large international multicenter collection— results listed per site; NR not reported

Topical Amphotericin B

Topical amphotericin B is not systemically absorbed and can be a useful adjunct therapy in patients with extensive burn injuries when used at lower concentrations (2 μg/ml) without systemic absorption [33]. Higher amphotericin B concentrations have been shown to be toxic in experiments using cultured human cells, but no direct clinical data are available [34]. Finally, nanoemulsion gels that allow for continuous delivery of amphotericin B in mucocutaneous fungal infections are undergoing clinical testing in Europe and may provide additional options in the near future [35, 36].

Conclusion

Patients with significant burn injuries present distinct infectious challenges to clinicians, often presenting with unusual infections that may not manifest themselves until days or weeks after initial admission. These patients often have multiple potential implicated causative pathogens, and it can be difficult to determine which is responsible for the patient’s symptoms. Infections with environmental fungi from the fungal order Mucorales are frequently aggressive, difficult to diagnose and resistant to many traditional antifungal agents. Although there are limited published clinical data in burn patients, our experience combining the newer systemic antifungal isavucona-zole alongside topical amphotericin B washes suggests this combination holds promise for effective Muco-rales treatment with a reduced toxicity profile. Whether the potential therapeutic benefits of isavu-conazole compared with posaconazole or amphotericin B are broadly clinically relevant in burn patient population is an understudied issue that deserves further attention.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Beth K. Thielen, Department of Medicine (Division of Infectious Diseases and International Medicine), University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA thie0149@umn.edu; Department of Pediatrics (Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology), University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Aaron M. T. Barnes, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; Department of Microbiology & Immunology, University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

Arick P. Sabin, Department of Medicine (Division of Infectious Diseases and International Medicine), University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA

Becky Huebner, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN 55415, USA.

Susan Nelson, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN 55415, USA.

Elizabeth Wesenberg, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN 55415, USA.

Glen T. Hansen, Department of Medicine (Division of Infectious Diseases and International Medicine), University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA Glen.Hansen@hcmed.org Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN 55415, USA.

References

- 1.Struck MF, Gille J. Fungal infections in burns: a comprehensive review. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2013;26:147–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaur R, Bala K, Ahuja RB, Srivastav P, Bansal U. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis in a patient with burn wounds due to Lichtheimia ramosa. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muszewska A, Pawlowska J, Krzyściak P. Biology, sys-tematics, and clinical manifestations of zygomycota infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1273–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley TT, Muzny CA, Swiatlo E, Legendre DP. Breaking the mold: a review of mucormycosis and current pharmacological treatment options. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:747–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmakiotis D, Kontoyiannis DP. Mucormycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:143–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skiada A, Pagano L, Groll A, Zimmerli S, Dupont B, Lagrou K, et al. Zygomycosis in Europe: analysis of 230 cases accrued by the registry of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) working group on zygomycosis between 2005 and 2007. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1859–67. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell TA, Hardin MO, Murray CK, Ritchie JD, Cancio LC, Renz EM, et al. Mucormycosis attributed mortality: a seven-year review of surgical and medical management. Burns. 2014;40:1689–95. 10.1016/j.burns.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Chakrabarti A, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ervens J, Ghannoum M, Graf B, Schwartz S. Successful isavuconazole salvage therapy in a patient with invasive mucormycosis. Infection. 2014;42:429–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriquez Tudela JL, Donnelly JP, Arendrup MC, Arikan S, Barchiesi F, Bille J, et al. EUCAST technical note on fluconazole: the European Committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing—subcommittee on antifungal susceptibility testing (EUCAST-AFST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:193–5. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos SRCJ Campos EV, Sanches C Gomez DS, Ferreira MC. Fluconazole plasma concentration measurement by liquid chromatography for drug monitoring of burn patients. Clinics. 2010;65:237–43. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1807-59322010000200017&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. Accessed 26 June 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann K, Pawlowska J, Walther G, Wrzosek M, de Hoog GS, Benny GL, et al. The family structure of the Mucorales: A synoptic revision based on comprehensive multigene-genealogies. Persoonia Mol Phylogeny Evol Fungi. 2013;30:57–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Hermoso D, Dromer F, Alanio A, Lortholary O. Agents of systemic and subcutaneous mucormycosis and entomophthoromycosis In: Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, Funke G, Landry ML, Richter SS, Warnock DW, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 11th ed. American Society of Microbiology; 2016. p. 2087–108. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165rv13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B. Identification of molds by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization—time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrödl W, Heydel T, Schwartze VU, Hoffmann K, Große-Herrenthey A, Walther G, et al. Direct analysis and identification of pathogenic Lichtheimia species by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight analyzer-mediated mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo PC, Leung S-Y, Ngan AH, Lau SK, Yuen K-Y. A significant number of reported Absidia corymbifera (Lich-theimia corymbifera) infections are caused by Lichtheimia ramosa (syn. Lichtheimia hongkongensis): an emerging cause of mucormycosis. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2012;1:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziaee A, Zia M, Bayat M, Hashemi J. Molecular identification of Mucor and Lichtheimia species in pure cultures of Zygomycetes. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2016;9:e35237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bibashi E, De Hoog GS, Pavlidis TE, Symeonidis N, Sakantamis A, Walther G. Wound infection caused by Lichtheimia ramosa due to a car accident. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2013;2:7–10. https://doi.org/10.10167j.mmcr.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christiaens G, Hayette MP, Jacquemin D, Melin P, Mutsers J, De Mol P. An outbreak of Absidia corymbifera infection associated with bandage contamination in a burns unit. J Hosp Infect. 2005;61:88 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16054948 Accessed 26 June 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson M, Lass-Flörl C. Changing epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;4:5–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miceli MH, Lee SA. Emerging moulds: epidemiological trends and antifungal resistance. Mycoses. 2011;54:e666–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park BJ, Pappas PG, Wannemuehler KA, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Andes DR, et al. Invasive non-Aspergillus mold infections in transplant recipients, United States, 2001–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1855–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamoth F, Calandra T. Early diagnosis of invasive mould infections and disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:i19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontoyiannis DP, Yang H, Song J, Kelkar SS, Yang X, Azie N, et al. Prevalence, clinical and economic burden of mucormycosis-related hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingram PR, Suthananthan AE, Rajan R, Pryce TM, Sieu-narine K, Gardam DJ, et al. Cutaneous mucormycosis and motor vehicle accidents: findings from an Australian case series. Med Mycol. 2014;52:819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, Walther G, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. Antifungal susceptibility profile of human-pathogenic species of Lichtheimia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3058–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vitale RG, De Hoog GS, Schwarz P, Dannaoui E, Deng S, Machouart M, et al. Antifungal susceptibility and phy-logeny of opportunistic members of the order Mucorales. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arendrup MC, Jensen RH, Meletiadis J. In vitro activity of isavuconazole and comparators against clinical isolates of the Mucorales order. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7735–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Natesan SK, Chandrasekar PH. Isavuconazole for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis and mucormycosis: current evidence, safety, efficacy, and clinical recommendations. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;9:291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miceli MH, Kauffman CA. Isavuconazole: a new broad-spectrum triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pendleton RA, Holmes JH. Systemic absorption of amphotericin B with topical 5% mafenide acetate/amphotericin B solution for grafted burn wounds: Is it clinically relevant? Burns. 2010;36:38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barsoumian A, Sanchez CJ, Mende K, Tully CC, Beckius ML, Akers KS, et al. In vitro toxicity and activity of Dakin’s solution, mafenide acetate, and amphotericin B on filamentous fungi and human cells. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:428–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussain A, Singh VK, Singh OP, Shafaat K, Kumar S, Ahmad FJ. Formulation and optimization of nanoemulsion using antifungal lipid and surfactant for accentuated topical delivery of amphotericin B. Drug Deliv. 2016;7544:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sosa L, Clares B, Alvarado HL, Bozal N, Domenech O, Calpena AC. Amphotericin B releasing topical nanoemulsion for the treatment of candidiasis and aspergillosis. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2017;13:2303–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]