Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to determine if hand joints develop an accelerated form of osteoarthritis and characterize individuals who develop accelerated hand osteoarthritis (AHOA).

Methods:

We evaluated 3519 participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative with complete data for baseline and 48-month radiographic hand osteoarthritis. One reader scored posteroanterior radiographs of the dominant hand using a modified Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) scale and another reader scored the presence of central or marginal erosions. A third reader read images flagged for signs of diseases other than osteoarthritis. We defined AHOA as ≥1 joints that progressed from a KL grade of 0 or 1 at baseline to KL 3 or 4 at 48 months.

Results:

The definition of AHOA was met by 1% over 4 years: 37 hands had 1 joint affected and 1 hand had 2 joints affected. At baseline, adults who developed AHOA were more likely to have hand pain (37% vs 22%), radiographic hand osteoarthritis (71% vs 36%), as well as central (22% vs 7%) and marginal erosions (11 vs 2%) in other joints compared to those without AHOA. Adults with AHOA were more likely to develop new erosions over 48 months (central 35%; marginal 5%) than those without AHOA (central 5%; marginal 1%). The most common locations of accelerated osteoarthritis were the second metacarpophalangeal and first carpometacarpal joint.

Conclusion:

Accelerated osteoarthritis can occur in the hand, especially among digits commonly used for pinching and fine motor skills.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, hand, epidemiology

Hand osteoarthritis (HOA) is a painful and debilitating disease, as well as the most frequent location of osteoarthritis [1]. There may be considerable heterogeneity within this condition, which previous investigators have tried to divide into subsets based on the presence of erosions or affected joints (e.g., distal interphalangeal [DIP] [2], proximal interphalangeal [PIP] or thumb-base) [3–5].

Previous studies have explored incidence of HOA [4, 6–9], but few have assessed the incidence of subsets of HOA [4, 6, 10, 11]. For example, within the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI), 19% of people developed radiographic osteoarthritis in at least one DIP or PIP over four years, but only 3% developed erosive osteoarthritis [4]. Assessing the onset of HOA subsets is challenging because there are few large cohorts with sufficient sample size to longitudinally explore the potential subsets [7].

A potentially underexplored subset of HOA is individuals who experience a dramatic accelerated rate of osteoarthritis onset. Larger joints such as the knee, hip and less frequently shoulder may develop an accelerated form of osteoarthritis [12–19]. Adults who develop accelerated knee osteoarthritis, in which they progress from normal radiographic appearance to advance-stage disease within 4 years and often in less than 12 months, report more pain and dysfunction than adults who develop a more gradual onset of osteoarthritis [2, 20, 21]. It is unknown whether such a novel subset of osteoarthritis exists among small joints in adults, particularly the joints of the hand. Therefore, we aimed to determine if hand joints develop an accelerated form of osteoarthritis, characterize individuals who develop accelerated HOA, and compare them to those who do not. We anticipate that those with accelerated HOA will have more erosions, particularly central erosions, than those without accelerated HOA because central erosions are a risk factor for cartilage loss [22].

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

To characterize accelerated HOA, we identified individuals using data from baseline and the 48-month follow-up visit of the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI). The OAI is a multicenter cohort study of 4,796 adults with or at risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Four clinical sites (Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, The Ohio State University, University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University, and the University of Pittsburgh) recruited participants between February 2004 and May 2006. OAI data and protocols are available for free public access [23]. Institutional review boards at each OAI clinical site and the OAI coordinating center (University of California, San Francisco) approved the OAI study. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Participant selection

We initially evaluated 3,616 participants in the OAI with good quality radiographs of the dominant hand at baseline and 48-month visits. We excluded 19 people who had radiographic evidence suggestive of a musculoskeletal pathology other than osteoarthritis (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteitis, gout, ankylosis; n=3,597). These findings were initially identified by one reader (IKH) and confirmed by a musculoskeletal radiologist (SES). To minimize misclassification, we also excluded 78 people because a reader was unable to assess radiographic severity (Kellgren-Lawrence [KL] grade) at 16 joints (i.e., 12 finger joints, 4 thumb joints) because of hand positioning (n=3,519).

Dominant hand

The OAI staff asked study participants if they were right or left handed and 95% of participants responded with left or right. If a participant answered ambidextrous or unknown or if data was missing, then we used standardized rules to define the dominant hand: 1) if the person had unilateral hand radiographs then we selected the imaged hand (4%) and 2) if the person had bilateral hand radiographs we selected the dominant hand based on the ipsilateral hand to the foot a participant reported using to kick a ball (1%).

Hand radiographs

Staff at each OAI site collected posteroanterior radiographs of the dominant hand of each participant at baseline and 48 months. The positioning of the hand required the participant to be placed with the elbow flexed 90 degrees and the forearm flat against the table. While most participants had unilateral hand radiographs, only 22% had bilateral images; hence, our work focused on the dominant hand.

Hand radiographic readings

Using the radiographs, readers scored 16 joints of the dominant hand: 2nd–5th DIP joints, 2nd–5th PIP joints, 1st–5th MCP joints, thumb interphalangeal (IP) joint, and the thumb-base joints: first carpometacarpal (CMC) joint and scaphotrapezial (STT) joint [11]. Specifically, a radiology fellow (LFS), who was trained for this project by a Board Certified musculoskeletal radiologist (SES), scored radiographic severity using a modified KL scale. A software displayed baseline and follow-up images side by side but blinded the reader to time. The modified KL scale was used in the Framingham Study [6]: KL 0=no osteoarthritis (no osteophyte or joint space narrowing), KL 1=questionable osteophyte or joint space narrowing, KL 2=small osteophyte(s) or mild joint space narrowing, KL 3=moderate osteophyte(s) or joint space narrowing, KL 4=large osteophyte(s) or joint space narrowing. LFS scored 100 randomly selected pairs of hand radiographs twice, with good intra-reader agreement (weighted kappa > 0.84 across 16 joints).

Another reader (IKH) scored the presence of central or marginal erosions (kappa > 0.79 across joints from 70 hands). The presence of central erosions was reported according to the Osteoarthritis Research Society International atlas [25]. The presence of marginal erosions was reported based on the Sharp-van der Heijde method [26]. However, in contrast to this method, we also scored the DIP joints, as they are frequently affected in HOA, and only the thumb-base joints were scored in the wrist. Central and marginal erosions were scored because prior reports indicate that both may be identified among people with HOA [10, 27–29].

Definition of accelerated HOA

We defined incident accelerated HOA as a hand with at least one joint that progressed from no radiographic osteoarthritis (KL = 0 or 1) at baseline to advance-stage disease at 48-months (KL = 3 or 4). A strength of this definition is that it typically requires a change in osteophytes and joint space. We previously validated this definition for accelerated knee osteoarthritis [21].

Avoiding Misclassification

Readings from the radiology fellow were sent to a rheumatologist with an expertise in HOA epidemiology (IKH). The rheumatologist added scores for specific joint features (e.g., presence of central erosions) and flagged hands when she had concerns of pathology unrelated to osteoarthritis. The flagged hands were then sent to the Board Certified musculoskeletal radiologist who reviewed the images and offered a final opinion on whether the person should be excluded due to radiographic evidence of other pathology. Finally, a rheumatologist (TEM) reviewed medication use among participants with possible accelerated HOA to determine if anyone should be excluded based on indications of treatment for an inflammatory condition.

Participant characteristics

We selected demographic, anthropometric, and additional participant characteristics. These were acquired based on a standard protocol [23]. Specifically, we extracted several key baseline variables: age, body mass index (BMI), sex, and radiographic status. We also derived a person’s baseline menopause status and the presence of metabolic syndrome using publicly available data. Menopausal status at baseline was based on a woman’s response to “When was your last natural menstrual period? Do not include bleeding due to taking female hormone pills or patches.” Based on this question, we classified a woman into three states: 1) premenopause if she indicated that she had a natural menstrual period “within the past 12 months”, 2) perimenopause if she indicated that she had a natural menstrual period in “1 to 2 years ago” or “3 to 4 years ago”, and 3) postmenopause if she answered “5 or more years ago”. We excluded women who did not know when their last natural menstrual period occurred. If a woman left this question unanswered and she reported a history of a hysterectomy, then we considered her in perimenopause if the hysterectomy was in the 5 years prior to OAI baseline and postmenopause if the hysterectomy was reported 5 or more years prior to the baseline visit. The presence of metabolic syndrome was defined by having at least 2 of 4 criteria: 1) self-reported diabetes on the Charlson Comorbidity Index, 2) use of cholesterol medication (derived from a medication inventory form), 3) high blood pressure (systolic pressure≥130 or diastolic pressure≥85) or use of hypertension medication (derived from a medication inventory form), and 4) central adiposity based on sex-specific cutoffs for weight circumference. Additionally, participants were asked at baseline about hand pain: “During the past 30 days, which of these joints have had pain, aching, or stiffness on most days? By most days, we mean more than half the days of a month.” Participants would then indicate left or right hand [23]. The baseline variables were extracted from the allclinical00 (version 0.2.2) and mif00 (version 0.2.2) files, which are available on the OAI website.

At each OAI follow-up visit, the OAI staff asked participants if a doctor said they broke or fractured hand bone(s) since their last visit about 12 months prior. The participant then answered yes or no (files: allclinical01 [version 1.2.1], allclinical03 [version 3.2.1], allclinical05 [version 5.2.1], allclinical06 [version 6.2.1]).

Statistical methods

We calculated descriptive statistics to characterize people with and without accelerated HOA. For categorical variables we calculated the differences in frequency between those with and without accelerated HOA and the Wald (Asymptotic) 95% confidence limits. For continuous measures, we calculated the mean differences and the 95% confidence limits based on pooled and Satterthwaite 95% intervals depending on whether variances were equal or not between groups, respectively. We conducted an exploratory logistic regression to test the association between incident accelerated HOA and 5 baseline characteristics in one model (i.e., sex, presence of radiographic HOA, presence of central erosions, body weight, and age). As a sensitivity analysis, we calculated the descriptive characteristics for people with and without accelerated HOA among those who had no joints with advance-stage disease in the dominant hand at baseline (KL=3 or 4). Results were generated using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (Cary, NC).

Ethical standards

The OAI was approved and meets all criteria for ethical standards regarding human and animal studies defined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and all amendments made after. Institutional review boards at each OAI clinical site and the OAI coordinating center (University of California, San Francisco) approved the OAI study (approval number 10–00532). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

RESULTS

We analyzed data from 3,519 participants. There were no meaningful differences between OAI participants included (n=3519) or excluded (n=1277) from these analyses for age (included: 60.8±9.2 years vs excluded: 62.2±9.0 years), BMI (28.7±4.9 kg/m2 vs 28.4±4.8 kg/m2), or proportion of females (58% vs 60%), presence of hand pain (28% vs 29%), or self-reported diagnosis of HOA (17% vs 16%).

The definition of accelerated HOA was met by 1% (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.8 to 1.5%) over 4 years: 37 hands had 1 joint affected and 1 hand had 2 joints affected.

At baseline the accelerated HOA group was slightly more female (74% vs 57%), older (64.9 vs 61.0 years), and more likely to have hand pain (37% vs 22%; Table 1). Only 1 person (3%) with accelerated HOA had a fracture during the observation period, compared to 56 people (2%) with fractures in the control group. Additionally, 8% of adults with accelerated HOA also developed accelerated knee osteoarthritis, compared with 3% of adults without accelerated HOA. When we calculated the descriptive characteristics among adults without advance-stage disease in the dominant hand at baseline we found similar results (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adults Who Develop Accelerated Hand Osteoarthritis (HOA)

| No Accelerated HOA n=3481 mean (SD) or n (%) | Accelerated HOA n=38 mean (SD) or n (%) | Difference Between Groups (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Female n (%) | 1993 (57%) | 28 (74%) | 16% (2 to 31%)a |

| Pre-menopause n (%) | 298 (15%) | 2 (7%) | −8% (−18 to 2%) |

| Peri-menopause n (%) | 274 (14%) | 2 (7%) | −7% (−16 to 3%) |

| Post-menopause n (%) | 1411 (71%) | 24 (86%) | 15% (1% to 28%) |

| Metabolic Syndrome (2–4 components) n (%) | 1914 (57%) | 23 (61%) | 3% (−13 to 19%)a |

| Self-Reported Diabetes n (%) | 235 (7%) | 1 (3%) | −4% (−9 to 1%) |

| Use of Lipid Medications n (%) | 983 (28%) | 11 (29%) | 1% (−14 to 15%) |

| High Blood Pressure n (%) | 2079 (59%) | 24 (63%) | 4% (−12% to 19%) |

| Large Waist Circumference n (%) | 2540 (75%) | 29 (76%) | 2% (−12 to 15%)a |

| Physician Diagnosed HOA n (%) | 534 (15%) | 16 (42%) | 27% (11 to 43%) |

| Prevalent Hand Pain n (%) | 756 (22%) | 14 (37%) | 15% (0 to 31%) |

| Age (years) | 61.0 (9.1) | 64.9 (8.3) | 3.9 (1.0 to 6.8) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.5 (4.8) | 27.4 (4.5) | −1.1 (−2.7 to 0.4) |

| Body Weight (kg) | 81.2 (16.2) | 74.3 (14.5) | −6.9 (−12.1 to −1.7) |

| Baseline radiographic hand characteristics | |||

| Radiographic HOA n (%) | 1236 (35%) | 27 (71%) | 36% (21 to 50%) |

| Central Erosions (≥ 1 joint) n (%) | 233 (7%) | 8 (22%) | 15% (2 to 28%) |

| Marginal Erosions (≥ 1 joint) n (%) | 81 (2%) | 4 (11%) | 8% (−2 to 18%)a |

| Number of Joints with KL ≥ 3 | 0.5 (1.2) | 1.1 (2.0) | 0.6 (−0.02, 1.3) |

| Incident Findings Over Time | |||

| Incident Accelerated Knee Osteoarthritis n (%) | 105 (3%) | 3 (8%) | 5% (−4 to 13%) |

| New Central Erosions Over 48 months n (%) | 158 (5%) | 13 (35%) | 31% (15 to 46%)a |

| New Marginal Erosions Over 48 months n (%) | 50 (1%) | 2 (5%) | 4% (−3 to 11 %) |

collected at baseline

discordance in group difference is related to rounding.

Notes on missing data: Only included people with body weight, and status of self-reported hand pain (yes or no) and physician diagnosed HOA (yes and no or unknown) at baseline. Missing data: Less than 3% missing data for menopause status, central erosions, marginal erosions, diabetes status, and waist circumference. Metabolic syndrome (n missing = 137 controls). No other missing data.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Adults Who Develop Accelerated Hand Osteoarthritis (HOA) With No Joints With Advance-Stage Disease (Kellgren-Lawrence Grade 3 or 4) At Baseline

| No Accelerated HOA n=2741 mean (SD) or n (%) | Accelerated HOA n=21 mean (SD) or n (%) | Difference Between Groups (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Female n (%) | 1495 (55%) | 16 (76%) | 22% (3 to 40%)a |

| Pre-menopause n (%) | 290 (20%) | 2 (13%) | −7% (−2.3 to 9%) |

| Peri-menopause n (%) | 250 (17%) | 1 (6%) | −11% (−23 to 1%) |

| Post-menopause n (%) | 947 (64%) | 13 (81%) | 18% (−2% to 37%)a |

| Metabolic Syndrome (2–4 components) n (%) | 1369 (54%) | 10 (50%) | −4% (−26 to 18%) |

| Self-Reported Diabetes n (%) | 177 (7%) | 1 (5%) | −2% (−11 to 8%) |

| Use of Lipid Medications n (%) | 690 (26%) | 4 (20%) | −6% (−24 to 12%) |

| High Blood Pressure n (%) | 1492 (56%) | 13 (65%) | 9% (−12% to 30%) |

| Large Waist Circumference n (%) | 1877 (73%) | 13 (65%) | −8% (−29 to 13%) |

| Physician Diagnosed HOA n (%) | 285 (10%) | 5 (24%) | 13%(−5 to 32%)a |

| Prevalent Hand Pain n (%) | 470 (17%) | 9 (43%) | 26% (5 to 47%)a |

| Age (years) | 59.1 (8.6) | 62.4 (8.0) | 3.3 (0.43 to 7.0) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.6 (4.9) | 27.4 (4.8) | −1.2 (−3.3 to 0.9) |

| Body Weight (kg) | 82.3 (16.5) | 75.3 (14.2) | −7.0 (−12.1 to-1.7) |

| Baseline radiographic hand characteristics | |||

| Radiographic HOA n (%) | 629 (23%) | 12 (57%) | 34% (13 to 55%) |

| Central Erosions (≥ 1 joint) n (%) | 5 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | −0.1% (0.0 to 0.3%) |

| Marginal Erosions (≥ 1 joint) n (%) | 51 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 3% (−6 to 13%)a |

| Incident Findings Over Time | |||

| Incident Accelerated Knee Osteoarthritis n (%) | 78 (3%) | 1 (5%) | 2% (−7 to 11 %) |

| New Central Erosions Over 48 months n (%) | 24 (<1%) | 6 (30%) | 29% (9 to 49%) |

| New Marginal Erosions Over 48 months n (%) | 28 (1%) | 1 (5%) | 4% (−6 to 14%) |

collected at baseline

discordance in group difference is related to rounding.

Notes on missing data: Only included people with body weight, and status of self-reported hand pain (yes or no) and physician diagnosed HOA (yes and no or unknown) at baseline. Missing data: Less than 3% missing data for menopause status, central erosions, marginal erosions, diabetes status, and waist circumference. Metabolic syndrome (n missing = 137 controls). No other missing data.

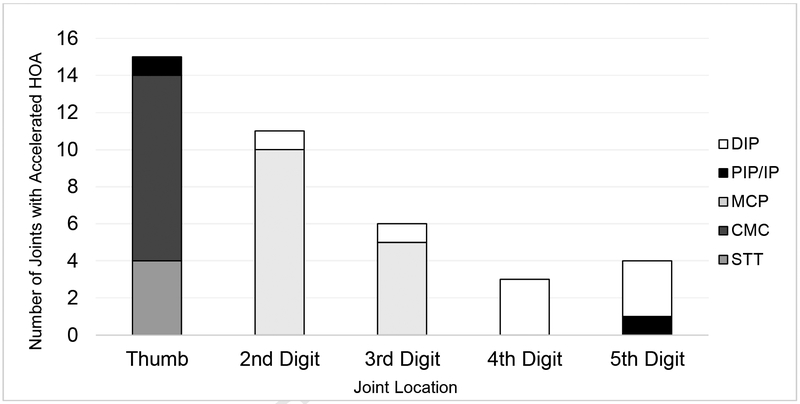

Location of accelerated HOA

Over 48 months, the most common locations of accelerated HOA were the thumb and second digit (Figure 1). The most commonly affected joints were the MCP2 and CMC1, which both had 10 cases.

Figure 1.

Patterns of Accelerated Hand Osteoarthritis (HOA) by Location

Baseline radiographic characteristics

At baseline, adults who developed accelerated HOA were more likely to have radiographic HOA (KL≥2) in at least one other joint (71% vs 36%), at least one joint with central erosions (22% vs 7%), and at least one joint with marginal erosions (11% vs 2%) compared to those who did not develop accelerated HOA (Table 1). Most erosions were at joints other than the joint that developed accelerated HOA (Table 3), with only one person having a marginal erosion at a joint that developed accelerated HOA (MCP2). Overall, these results were similar among adults with no advance-stage disease in the dominant hand at baseline; except for no group difference for the presence of baseline central erosions (0% vs <1%; Table 2).

Table 3.

Type and Location of Erosions Among Adults with Accelerated Hand Osteoarthritis (HOA) (n = 38)

| Hands with erosion at joint with accelerated HOA (n) |

Hands with erosion at a joint without accelerated HOA (n) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Erosion | ||

| Central Erosion | 0 | 8 |

| Marginal Erosion | 1 | 3 |

| New Erosion Over 48 months | ||

| Central Erosion | 7 | 9 |

| Marginal Erosion | 1 | 1 |

Note: 6 people had both baseline erosions and new erosions

Exploratory multivariable analysis of baseline characteristics

Our exploratory analysis was one model that included 5 baseline characteristics: (i.e., sex, presence of radiographic HOA, presence of central erosions, body weight, and age). We found that only the presence of radiographic HOA was associated with incident accelerated HOA (odds ratio=4.3, 95% CI=1.8 to 10.3, p=0.001). The other variables had p values > 0.40; except weight (p=0.09).

Radiographic characteristics over time

Adults with accelerated HOA were more likely to develop new erosions in either the same or another joint over 48 months (central 35%; marginal 5%) than those who did not develop accelerated HOA (central 5%; marginal 1%). These results were similar among adults without advance-stage disease in the dominant hand at baseline (Table 2). Eight people (21%) who developed accelerated HOA had an incident erosion in the same joint that worsened, with only one of them being marginal and the remaining 7 being a central erosion. Ten people (26%) with accelerated HOA developed an incident erosion at a joint other than the one with accelerated progression. Similarly, only one of those was marginal and 9 were central (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We identified and characterized accelerated HOA and found that the affected joints are most common in the thumb-base and second MCP joints, which are commonly used for fine motor skills like a pincer grasp. Furthermore, people with radiographic osteoarthritis in other hand joints, particularly with erosions, were more likely to develop accelerated HOA. Hence, accelerated HOA may be a subset of HOA that is associated with erosive HOA. This supports the notion that erosive HOA is a more rapid progressing phenotype.

We found that accelerated HOA manifested overwhelmingly at CMC1 and MCP2. While osteoarthritis at CMC1 is fairly common [5], the prevalence of MCP osteoarthritis is low and more common among men (11.9% in men, 6.8% in women) [6]. The few investigators who explored osteoarthritis in MCP joints found that when these joints are affected, the prevalence is higher at MCP1, MCP2, and MCP3 [6, 10, 30]. Osteoarthritis of MCP joints may be associated with heavy labor since forces are higher at these joints than the more distal ones (DIP or PIP joints) [6, 31, 32]. With the high occurrence of accelerated HOA at MCP2 and the thumb, both involved in gripping, it’s possible that individuals involved in manual labor may be more at risk for accelerated osteoarthritis at these proximal joints because stresses are higher than at distal joints. Future studies with occupational and hand function data should test these claims, as well as investigate how much of MCP osteoarthritis may be accelerated osteoarthritis.

We detected a relationship between hand erosions and accelerated HOA; although they often occurred in different joints within the hand. The onset of hand erosions or accelerated HOA are more common among those with radiographic HOA at baseline compared with those without HOA [22, 29]. When we excluded people with advance- stage disease at baseline we still observed a possible relationship between incident accelerated HOA and new central erosions; despite the absence of a relationship between accelerated HOA and baseline central erosions. These seemingly contradictory findings may be explained by a bias introduced in the cross-sectional analysis by excluding those with advanced-stage disease at baseline.

Erosions are typically found among those with inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, so finding them frequently in accelerated HOA was particularly interesting [3, 22]. Erosions at MCP joints would suggest an inflammatory condition; however, only one person had an erosion at an MCP joint. The rest of the erosions were heavily weighted towards the IP joints, with a few at the CMC and STT joints, which is consistent with HOA.

It would be particularly interesting to examine the potential differences between the roles of central versus marginal erosions, especially since central erosions are a risk factor for cartilage loss [28]. Previous magnetic resonance imaging studies have suggested that marginal erosions may be more common in HOA than we have been able to demonstrate using conventional radiographs [38–40]. However, we acknowledge that the clinical importance is unknown, since few studies explored the prevalence and role of marginal erosions in HOA. Marginal erosions are typical among other rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. However, one or few marginal erosions are unspecific and do not necessarily indicate an individual has an inflammatory joint disease.

The relationship between erosive HOA and accelerated HOA should be further explored because they may share common causes or risk factors or be closely related subsets [33]. For example, HOA, particularly erosive HOA, has been associated with reduced bone mineral content and density in the hand and wrist [34–36]. This is relevant due to prior studies associating accelerated osteoarthritis at large joints with significant bone damage [19, 37].

There were slight differences in our demographics and participant characteristics, where we found that people with accelerated HOA tended to be more female, slightly older, and more likely to report pain. Certain phenotypes within HOA differ between sexes (e.g. joint location, erosive osteoarthritis) [6]. Our findings complement a prior study where the investigators found that erosive HOA, which may be related to accelerated HOA, was mainly found among women [6]. Additionally, those with accelerated HOA were more likely to report hand pain at baseline than those without accelerated HOA. This is consistent with our findings that accelerated knee osteoarthritis is also often preceded by more knee pain than common knee osteoarthritis and that pain may precede accelerated structural changes [2, 11, 20].

While our study identified accelerated osteoarthritis in hands, we acknowledge that there are limitations. With a larger sample size, it could be possible to explore more complex interactions between risk factors. Even with a smaller sample size of cases, we were able to identify potentially important characteristics and patterns of those with accelerated HOA. Additionally, without extensive lab work, we depended solely on radiographs and medication use to eliminate other types of arthritis, so it is possible that some people may have still been misclassified despite our best effort. Another limitation was our reliance on dominant hand radiographs because bilateral images were only collected on ~20% of participants. Prior investigators suggested that nondominant thumb-base osteoarthritis may be more common than in the dominant hand [5, 6]. It would be beneficial to have bilateral hand radiographs to determine if accelerated osteoarthritis at CMC1 is more prevalent than we found. The lack of radiographs for the nondominant hand does not alter the take-home message that accelerated osteoarthritis occurs in hands and warrants further study. We may also be limited by defining accelerated HOA based on disease onset at just one joint. By including hands with only one affected joint we may be including joints that develop accelerated osteoarthritis because of trauma; however, this was the goal since accelerated osteoarthritis at the knee is related to joint trauma [12]. Future research will be needed to determine if accelerated osteoarthritis in the hand is also associated with joint trauma. We have also been cautious to minimize reference to incident accelerated osteoarthritis because we are unable to rule out that some joints experienced accelerated osteoarthritis prior to the OAI, having entered the study with a KL grade of 3 or 4 in one or more joints. In the current cohort, it would be infeasible because of the small number of cases to select the few hands where every joint has no radiographic osteoarthritis at baseline. Furthermore, baseline radiographic HOA is associated with accelerated osteoarthritis. If we exclude people with radiographic HOA at baseline we may introduce a selection bias. Hence, it may be valuable to further explore accelerated HOA among people under 45 years of age. Finally, the OAI is a rich dataset of individuals with or at-risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis and hence it is not a population-based study. Therefore, the incidence over 4 years and the observed associations may not reflect the general population and future studies may be warranted to explore how the estimated proportions of person with accelerated HOA and associations differs between the OAI and population-based cohorts. Despite this limitation, the OAI is a large dataset, which enabled us to confirm the presence of accelerated osteoarthritis in the hand and raise awareness about this novel subset of people with accelerated HOA.

In conclusion, we identified an accelerated form of osteoarthritis in hand joints. Accelerated HOA may be a unique phenotype where individuals are more likely to progress at the MCP2 and CMC1 joints. Those with accelerated HOA may be more likely to have radiographic HOA. Our results identify a phenotype of HOA underreported that present with radiographic differences and a concerning acceleration of HOA.

Acknowledgments

These analyses were financially supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01-AR065977 and Award Number R01-AR066378. The OAI is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2–2258; N01-AR-2–2259; N01-AR-2–2260; N01-AR-2–2261; N01-AR-2–2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public use data set and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners. This work was also supported in part by the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence (HFP90–020). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors have no other conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kalichman L, Cohen Z, Kobyliansky E, Livshits G. Patterns of joint distribution in hand osteoarthritis: Contribution of age, sex, and handedness. Am J Hum Biol 2004;16:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Driban JB, Price LL, Eaton CB, Lu B, Lo GH, Lapane KL, et al. Individuals with incident accelerated knee osteoarthritis have greater pain than those with common knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:1565–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gazeley DJ, Yeturi S, Patel PJ, Rosenthal AK. Erosive osteoarthritis: A systematic analysis of definitions used in the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haugen IK, Magnusson K, Turkiewicz A, Englund M. The Prevalence, Incidence, and Progression of Hand Osteoarthritis in Relation to Body Mass Index, Smoking, and Alcohol Consumption. J Rheumatol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilder FV, Barrett JP, Farina EJ. Joint-specific prevalence of osteoarthritis of the hand. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006;14:953–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haugen IK, Englund M, Aliabadi P, Niu J, Clancy M, Kvien TK, et al. Prevalence, incidence and progression of hand osteoarthritis in the general population: the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1581–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaisson CE, Zhang Y, McAlindon TE, Hannan MT, Aliabadi P, Naimark A, et al. Radiographic hand osteoarthritis: incidence, patterns, and influence of pre-existing disease in a population based sample. J Rheumatol 1997;24:1337–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Javaid MK, Cooper C, Diez-Perez A, Arden NK. “Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints”. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1659–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reyes C, Leyland KM, Peat G, Cooper C, Arden NK, Prieto-Alhambra D. Association between overweight and obesity and risk of clinically diagnosed knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1869–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addimanda O, Cavallari C, Pignotti E, Pulsatelli L, Mancarella L, Ramonda R, et al. Radiographic involvement of metacarpophalangeal and radiocarpal joints in hand osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:1077–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaefer LF, McAlindon TE, Eaton CB, Roberts MB, Haugen IK, Smith SE, et al. The associations between radiographic hand osteoarthritis definitions and hand pain: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Rheumatol Int 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driban JB, Eaton CB, Lo GH, Ward RJ, Lu B, McAlindon TE. Association of knee injuries with accelerated knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1673–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irwin LR, Roberts JA. Rapidly progressive osteoarthrosis of the hip. The Journal of Arthroplasty;13:642–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batra S, Batra M, McMurtrie A, Sinha A. Rapidly destructive osteoarthritis of the hip joint: a case series. J Orthop Surg Res 2008;3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutry N, Paul C, Leroy X, Fredoux D, Migaud H, Cotten A. Rapidly Destructive Osteoarthritis of the Hip: MR Imaging Findings. American Journal of Roentgenology 2002;179:657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Postel M, Kerboull M. Total prosthetic replacement in rapidly destructive arthrosis of the hip joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1970;72:138–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Della Torre P, Picuti G, Di Filippo P. Rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 1987;13:187–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T, Bullough PG. The role of subchondral insufficiency fracture in rapid destruction of the hip joint: a preliminary report. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:2423–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochberg MC. Serious joint-related adverse events in randomized controlled trials of anti-nerve growth factor monoclonal antibodies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:S18–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis J, Eaton CB, Lo GH, Lu B, Price LL, McAlindon TE, et al. Knee symptoms among adults at risk for accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:1083–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Driban JB, Stout AC, Lo GH, Eaton CB, Price LL, Lu B, et al. Best performing definition of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2016;8:165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schett G, Gravallese E. Bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Osteoarthritis Initiative. [cited 2014; Available from: http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/

- 24.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, Breslow NE, Cox DR, Howard SV, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer 1976;34:585–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman RD, Gold GE. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:A1–A56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Heijde D How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol 2000;27:261–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Addimanda O, Mancarella L, Dolzani P, Punzi L, Fioravanti A, Pignotti E, et al. Clinical and radiographic distribution of structural damage in erosive and nonerosive hand osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1046–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall M, Peat G, Nicholls E, van der Windt D, Myers H, Dziedzic K. Subsets of symptomatic hand osteoarthritis in community-dwelling older adults in the United Kingdom: prevalence, inter-relationships, risk factor profiles and clinical characteristics at baseline and 3-years. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1674–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall M, Nicholls E, Kwok W-Y, Peat G, Kloppenburg M, van der Windt D, et al. Erosive osteoarthritis: a more severe form of radiographic hand osteoarthritis rather than a distinct entity? Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta KB, Duryea J, Weissman BN. Radiographic evaluation of osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am 2004;42:11–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams WV, Cope R, Gaunt WD, Adelstein EH, Hoyt TS, Singh A, et al. Metacarpophalangeal arthropathy associated with manual labor (Missouri metacarpal syndrome). Clinical radiographic, and pathologic characteristics of an unusual degeneration process. Arthritis Rheum 1987;30:1362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaisson CE, Zhang Y, Sharma L, Felson DT. Higher grip strength increases the risk of incident radiographic osteoarthritis in proximal hand joints. Osteoarthritis Cartilage;8:S29–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boeters DM, Nieuwenhuis WP, van Steenbergen HW, Reijnierse M, Landewé RBM, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Are MRI-detected erosions specific for RA? A large explorative cross-sectional study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:861–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Sherif HE, Kamal R, Moawyah O. Hand osteoarthritis and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women; clinical relevance to hand function, pain and disability. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hochberg MC, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Tobin JD. Bone mineral density and osteoarthritis: Data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging1. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:45–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haara MM, Arokoski JPA, Kröger H, Kärkkäinen A, Manninen P, Knekt P, et al. Association of radiological hand osteoarthritis with bone mineral mass: a population study. Rheumatology 2005;44:1549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driban JB, Ward RJ, Eaton CB, Lo GH, Price LL, Lu B, et al. Meniscal extrusion or subchondral damage characterize incident accelerated osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Anat 2015;28:792–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyn TA, J. GA, F TS, M SD, Colin P, Paul E, et al. High‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of hand osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2355–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haugen IK, Boyesen P, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, Sesseng S, Bijsterbosch J, van der Heijde D, et al. Comparison of features by MRI and radiographs of the interphalangeal finger joints in patients with hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:345–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haugen IK, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, Bøyesen P, Sesseng S, van der Heijde D, Kvien TK. MRI findings predict radiographic progression and development of erosions in hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacGregor AJ, Li Q, Spector TD, Williams FM. The genetic influence on radiographic osteoarthritis is site specific at the hand, hip and knee. Rheumatology 2009;48:277–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]