Summary:

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) as a blood-based biomarker for mutation detection is an exciting, highly-sensitive approach in the clinical management of oncology patients. In HPV-associated malignancies like anal cancer, a viral-specific probe can be utilized for ctDNA detection in the majority of patients in order to predict clinical outcomes.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Bernard-Tessier and colleagues (1) demonstrate the clinical utility of a highly sensitive human papillomavirus (HPV) circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) assay as a prognostic biomarker in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal receiving frontline chemotherapy.

Anal cancer is a rare malignancy of the distal gastrointestinal tract for which over 90% of all cases are caused by prior exposure to HPV. Akin to other HPV-associated malignancies like oropharyngeal cancer and cervical cancer, HPV initially infects basal cells of squamous epithelium at sites of traumatic microperforations. High-risk oncogenic HPV subtypes, most commonly HPV-16 and HPV-18, transform affected cells into cancer via constitutive expression of the viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins(2). Here, E6 promotes anti-apoptotic activity and interruption of cell senescence through pathologic interactions with p53 and telomerase, respectively. Simultaneously, dysregulation of cell cycle checkpoint activity induces uncontrolled tumor cell proliferation due to E7-mediated suppression of Rb function. Together, oncoproteins E6 and E7 not only are ever present inside these cells but also are requisite for growth and continued existence of HPV-associated malignancies like anal cancer.

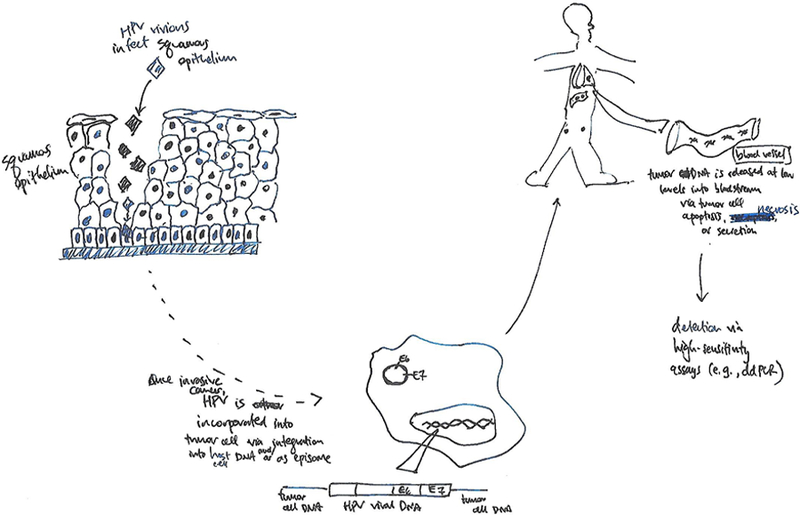

HPV DNA integrates into the host cell genome in approximately 80% of HPV-associated tumors, and resides as a viral episome in the remaining 20% of cases. Recent advances in sequencing technology have allowed for the detection of minute levels of circulating tumor DNA in patients’ plasma, released into the bloodstream predominantly following tumor cell apoptosis (Figure). Genomic profiling using ctDNA analysis is highly sensitive, able to detect somatic variant allelic frequencies as low as 0.1%, and outperforms traditional methods like Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing. Use of ctDNA has applicability across a variety of clinical settings in oncology, including, but not limited to, identification of minimal residual disease following definitive resection in early-stage cancers, monitoring dynamic changes serially in tumor burden as a response to systemic treatment, and identification of mechanisms of acquired resistance to a given therapy according to novel somatic clones uncovered in the ctDNA at the time of progression. While most commonly utilized to detect tumor-related mutations, a precedent has been successfully established for detection of viral ctDNA using a primer against the Epstein Barr virus (EBV) to screen patients at high risk for development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma(3). Until this point, a reliable blood-based HPV biomarker for patients with anal cancer has been lacking.

From infection to detection:

HPV infects basal cells of squamous epithelium at sites of traumatic microperforations and may incorporate into host cell chromosomal DNA or reside as a viral episome. Once transformed into a malignant cell, fragments of tumor DNA may be released into the bloodstream following cell apoptosis, necrosis, or secretion, where it can be detected and quantified with high-sensitivity assays.

In the Epitopes-HPV02 trial (1), patients with treatment-naïve, locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic anal cancer received frontline chemotherapy with the triple combination of docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DCF). Reported rates of grades 3 or 4 toxicity (70%) were high with this regimen, although objective responses were measured in 57 of 66 (86%) of evaluated patients. Blood was collected at two time points – prior to treatment initiation and at completion of (approximately 5 months of) chemotherapy. Serum was tested for HPV ctDNA using an HPV16-E7 primer on a droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assay in order to correlate HPV levels with clinical outcomes. In their design here, the authors selected an appropriate probe given the high prevalence of the HPV-16 subtype and the ubiquity of E7 expression in anal cancer.

HPV ctDNA was detectable in 52 of 57 (91%) baseline samples. ddPCR here was able to identify as few as 8 copies of HPV per mL blood. This low limit of detectability with this ddPCR assay expectedly exceeded the quantitative PCR analysis performance taken from the same blood samples, using an orthogonal validation of the ddPCR approach. Of note, when filtering out the six patients with non-metastatic, locally recurrent disease in this series, HPV ctDNA was identified in 49 of 51 (96%) pretreatment blood specimens from patients with distant metastatic disease. The findings reported here thereby suggest that testing for of HPV ctDNA may be optimal when limited to anal cancer patients with distant metastases.

In this present study(1), the persistence of HPV ctDNA following completion of the planned course of DCF chemotherapy served as a surrogate for the presence of residual disease. The median PFS in this ctDNA (+) subgroup of 3.4 months after chemotherapy completion corresponded to the time of first restaging. A positive ctDNA status then serves as a biomarker which identifies patients with metastatic anal cancer at high risk for progression and poor survival outcomes. On the other hand, patients with undetectable ctDNA after DCF had improved both PFS and overall survival. Not surprisingly, deeper radiographic responses were associated with decreasingly lower HPV levels in the serum, again a surrogate for a low/minimal total tumor burden. It remains unclear, for those whose ctDNA cleared with chemotherapy in this study, how quickly HPV ctDNA levels became undetectable, given the single time point of blood collection after treatment initiation. Further efforts to characterize better the kinetics of HPV ctDNA disappearance may inform clinicians on the optimal duration of chemotherapy in this setting. Here, an early clearance of HPV ctDNA may minimize the risk of treatment-related toxicities while still offering clinical benefit to patients with metastatic anal cancer who experience exceptional responses to systemic treatment as determined by this blood-based biomarker.

The authors also demonstrate that quantifiable HPV levels in the serum prior to treatment are prognostic for survival outcomes in patients with metastatic anal cancer. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis generated a baseline level of approximately 3000 HPV copies per mL blood that were associated with progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes on the DCF regimen, with higher pretreatment levels linked to the total volume of tumor burden and worsened survival outcomes. Similar findings demonstrating an increase in HPV levels in the blood with advancing clinical stage at diagnosis have been reported from a retrospective series of patients with HPV-positive head/neck, cervical, and anal cancers using the same HPV ctDNA probe(4).

Use of a pervasive viral biomarker in E7 here obviates the need for individualized probes tailored to the matched tumor genome of a given patient with anal cancer. In one series of metastatic anal tumors which underwent whole exome sequencing(5), a low overall mutation frequency was observed, with a median of 2.5 mutations per megabase (Mb) of DNA. Here, somatic mutation burden was similar to HPV-positive head/neck (2.8 mutations/Mb) and cervical cancers (3.4 mutations/Mb). Likewise PIK3CA was the most commonly mutated gene for all of these HPV-associated malignancies, present in approximately 30% of all tumors. In light of these known findings, use of a viral-specific probe extends the applicability of ctDNA technologies beyond traditional mutation detection with a single probe relevant across all anal cancers. The performance of this HPV ctDNA assay, as reported in this study, has now introduced a highly sensitive blood biomarker which should move towards incorporation into routine clinical monitoring for patients with any HPV-associated malignancy.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work is supported, in part, by NCI grant 5K12 CA088084.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflict of interest/relevant disclosures

References

- 1.Bernard-Tessier A, Jeannot E, David G, Debernardi A, Michel M, Proudhon C, et al. Clinical validity of HPV circulating tumor DNA in advanced anal carcinoma: an ancillary study to the Epitopes-HPV02 trial. Clin Cancer Res 2018. doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz E, Freese UK, Gissmann L, Mayer W, Roggenbuck B, Stremlau A, et al. Structure and transcription of human papillomavirus sequences in cervical carcinoma cells. Nature 1985;314(6006):111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan KCA, Woo JKS, King A, Zee BCY, Lam WKJ, Chan SL, et al. Analysis of Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus DNA to Screen for Nasopharyngeal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377(6):513–22 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1701717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeannot E, Becette V, Campitelli M, Calmejane MA, Lappartient E, Ruff E, et al. Circulating human papillomavirus DNA detected using droplet digital PCR in the serum of patients diagnosed with early stage human papillomavirus-associated invasive carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res 2016;2(4):201–9 doi 10.1002/cjp2.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris V, Rao X, Pickering C, Foo WC, Rashid A, Eterovic K, et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anal Canal. Mol Cancer Res 2017;15(11):1542–50 doi 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]