Abstract

Objective

Sexual concerns are often unaddressed for breast cancer patients; one reason is inadequate clinician training. We examined the feasibility, acceptability, and potential benefits of a novel intervention, iSHARE (improving Sexual Health and Augmenting Relationships through Education), for breast cancer clinicians.

Methods

Clinicians received training in communicating about sexual concerns with breast cancer patients. Intervention feasibility and acceptability were measured through enrollment/participation and post-intervention program evaluations, respectively. Intervention effects were assessed through (1) clinician self-reported beliefs about sexual health communication, assessed at baseline, post-intervention, and 1-/6-month follow-up, (2) clinical communication coded from audio recorded, transcribed clinic encounters at pre-/post-intervention, and (3) patient satisfaction with clinical care, reported immediately after the clinic visit. Patients also reported socio-demographic characteristics and level of sexual concerns.

Results

Seven breast cancer clinicians enrolled (88% participation) completed the intervention, and were audio recorded in clinic encounters with 134 breast cancer outpatients (67 each at pre-/post-intervention). Program evaluations supported intervention acceptability. Effect sizes suggest iSHARE increased clinicians’ self-efficacy (d=.27) and outcome expectancies for communicating about sexual concerns (d=.69) and reduced communication barriers (d=−.14). Clinicians’ sexual health communication behaviors increased from baseline to post-intervention, including for raising the topic (28% vs. 48%), asking questions (33% vs. 45%), and offering information (18 vs. 24%). Neither patient satisfaction nor duration of sexual health communication changed (mean duration < 1 minute at both time points).

Conclusions

The iSHARE intervention was feasible and well-received by clinicians, and may change breast cancer clinicians’ beliefs and communication behaviors regarding sexual health.

Keywords: Sexual Behavior, Reproductive Health, Communication, Breast Neoplasms, Cancer, Oncology, Women’s Health

Background

The life-extending treatments offered to women with breast cancer often impair sexual function and quality of life (QOL) [1–4]. Clinical cancer guidelines put forth by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommend that sexual function be addressed in patients with cancer along with other psychological and physical health issues [5, 6]. Yet cancer clinicians infrequently raise the topic of sexual health with patients [7], and fewer than half of women with breast cancer receive any sexual health communication [8, 9]. Thus, for many women with breast cancer suffering from sexual problems is likely unaddressed [6, 10, 11]. Lack of training is a key barrier contributing to breast cancer clinicians’ reluctance to raise the topic of sexual health with patients [12]. Given that breast cancer patients are unlikely to raise the topic on their own – even if they have sexual problems [9] – interventions that equip clinicians with the knowledge and skills to effectively discuss sexual concerns with patients are needed.

Unfortunately, few evidence-based interventions focused on enhancing breast cancer clinicians’ communication with respect to sexual health exist [13, 14]. To address this gap, we developed a brief intervention, iSHARE (improving Sexual Health and Augmenting Relationships through Education), that provides breast cancer clinicians with focused knowledge and skills training in discussing sexual health concerns with their patients. This study assessed the feasibility, acceptability, and potential benefits of iSHARE on clinicians’ beliefs and communication with respect to sexual health and, secondarily, on duration of sexual health communication and on patients’ satisfaction with care.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We used a mixed methods approach to evaluate the intervention. Participating breast cancer clinicians completed self-report outcome measures immediately after consent (i.e., pre-intervention), immediately post-intervention, and at 1-month and 6-month post-intervention follow-up. In addition, we audio recorded encounters between these clinicians and participating breast cancer patients for a period of 6 months before and after the intervention to assess intervention effects on clinicians’ communication. There was no overlap in the pre- and post-intervention patient groups. Study patients also completed a questionnaire about their clinic encounter immediately after the visit. The study setting was a comprehensive cancer center located in an urban setting. Approval was obtained by the Institutional Review Board at Fox Chase Cancer Center (IRB Protocol #14–833).

Study Sample

Participants in the study consisted of breast cancer clinicians and patients. All participants completed written consent prior to participation.

Clinician Participants

Of the nine oncologists and advanced practice clinicians treating breast cancer patients in the medical oncology clinics at Fox Chase Cancer Center, eight were eligible and invited to participate and one was excluded because he was exclusively treating patients in teaching clinics with fellows. Clinicians were compensated $500 for their time and effort.

Patient Participants

Women were eligible if they had a diagnosis of any stage breast cancer and were patients of participating clinicians, were being seen in follow-up (i.e., not consultation visit), and were either receiving treatment for breast cancer or had completed treatment within 10 years. Women were ineligible if they were unable to speak English, had poor physical performance, determined through an Eastern Cooperative Group Score (ECOG) [15] score > 2, or showed significant psychiatric or cognitive concerns.

iSHARE Intervention

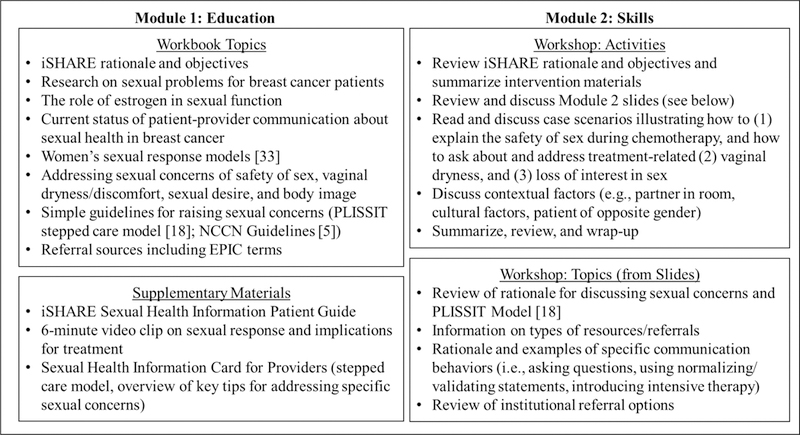

The iSHARE intervention was designed to deliver practical guidance to clinicians on discussing breast cancer-related sexual health in an effort to reduce communication barriers and facilitate effective communication. Grounded in social cognitive theory [16, 17], key intervention goals were to increase clinicians’ self-efficacy (i.e., confidence) and outcome expectancies (i.e., expectations for desired outcomes) for communicating with patients about sexual health. The intervention was also informed by a qualitative investigation we conducted with breast cancer patients and clinicians that identified barriers and facilitators of sexual health communication and intervention preferences [12]. As shown in Figure 1, iSHARE consisted of two modules, an educational module for individual self-study (i.e., informational workbook taking about 15 minutes and supplementary materials), and a manualized skills-based module that included participation in an in-person 60-minute small group workshop led by the PI (JBR). Two workshops with either 3 or 4 clinicians were held. The aim of the intervention was to equip clinicians to engage primarily in the first two steps of the stepped care PLISSIT framework for sexual counseling [18], specifically, giving patients permission (P) to discuss sexuality, such as by asking about sexual health, and offering limited information (LI) about sexual concerns. Clinicians were encouraged to give specific suggestions for addressing sexual problems (SS) if they felt comfortable, and information was given for referral for further evaluation and/or intensive therapy (IT).

Figure 1.

iSHARE Intervention Components

Data collection

Clinician-reported data

Clinicians completed self-report surveys assessing beliefs (self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, barriers to communication about sexual health) at four time points: immediately after consent (i.e., pre-intervention; see Appendix for full survey), immediately post-intervention, and at 1-month and 6-month post-intervention follow-up.

Patient-reported data

Immediately after the clinic visit, patients completed a questionnaire on sociodemographic characteristics, satisfaction with their clinician’s care [19], and sexual problems using an item from the Patient Care Monitor (PCM) [20] assessing problems with sexual interest, enjoyment, or performance over the past week (0–10 rating scale; higher scores=worse sexual problems). The PCM item is a reliable indicator of sexual problems in cancer populations [21–23].

Additional data

Medical data pertaining to patients’ cancer stage and date of diagnosis, menopausal status, and types of treatments received were obtained through chart review, with patients’ permission.

Measures

Feasibility and Acceptability

Feasibility and acceptability were measured through rates of enrollment, clinical participation in the intervention, and clinicians’ responses on post-intervention program evaluations assessing ease of participation, satisfaction with the program, and perceived clinical relevance and impact. Response options used a 5-point scale (0=strongly disagree/very dissatisfied to 4=strongly agree/very satisfied).

Clinician Beliefs about Sexual Health Communication

Self-efficacy.

Three items assessed clinicians’ self-efficacy for communicating with their breast cancer patients about physical types of sexual concerns, emotional types of sexual concerns, or generally. Response options used an 11-point scale (0=not at all confident/not at all to 10=extremely confident/very much). The scale had excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=.93). These items, and the outcome expectancy items (below) were developed for this study based on the social cognitive model [16], guidelines for developing self-efficacy scales [24], and expert review.

Outcome expectancies.

Seven items assessed clinicians’ outcome expectancies for communicating about sexual health with their patients (i.e., the extent to which clinicians believed that talking to their breast cancer patients about sexual health would lead to positive outcomes such as identifying patients who have sexual concerns). Response options used an 11-point scale (0=not at all confident/not at all to 10=extremely confident/very much). The scale had excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=.92).

Barriers to Communication about Sexual Health.

Fourteen items adapted from a prior published study [13] assessed clinicians’ perceived barriers to communication about sexual health. These items assessed a range of perceived communication barriers including embarrassment, fear of patients’ negative reactions, lack of skills or expertise, time constraints, and the belief that it is not the clinician’s role. Response options used a 6-point scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). This scale had good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=.80).

Clinical Communication

Overview.

Audio recordings of clinic encounters were transcribed and coded for sexual health communication using two levels of analysis. First, two coders determined the presence (y/n) of any sexual health communication, as described elsewhere [9]. Second, dialogue relevant to sexual health was coded using a codebook developed for this study, with coding difficulties resolved through discussion. Final codes were checked by a second coder for quality assurance.

Communication Behaviors and Duration of Sexual Health Discussion.

Two key clinician communication behaviors [8] selected a priori were: (1) asking questions about sexual health, defined as asking at least one question pertaining to sexual health or body image during the clinic encounter; and (2) offering information pertaining to sexual health, defined as offering either anticipatory counseling (related to the potential future possibility of treatment side effects) or counseling related to a current concern or issue reported by the patient. The complexity of these behaviors was also examined and defined as “neither asked nor offered,” “asked or offered” and “both asked and offered.” In addition, a qualitative analysis of the dialogue in a prior report [9] yielded two informative codes that we included in the present analysis to explore communication outcomes: (1) raising the topic (clinician initiated the discussion) of sexual health (0=no; 1=yes), regardless of other behaviors, and (2) raising the topic with counseling (e.g., “Many women on this treatment experience sexual concerns”; 0=no, 1=yes). The length of the discussion about sexual health in seconds was also recorded.

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was assessed using the Consumer Satisfaction Index, a four-item scale which assesses patients’ satisfaction with their clinician’s personal manner, communication skills, technical skills, and overall care [19]. Responses options used a 5-point Likert scale (1=excellent to 5=poor). Mean scale scores were used.

Statistical Methods

Feasibility and acceptability were analyzed using descriptive analyses (e.g., frequencies, measures of central tendency). Acceptability was determined by seventy-five percent of participants rating the training program favorably (“Agree”/”Strongly Agree” or “Satisfied”/”Very Satisfied”) on program evaluations at post-intervention. Descriptive analyses characterized the study sample. Patients at baseline and post-intervention were compared on socio-demographic and medical variables using Chi-square tests or t-tests; categorical variables (i.e., race, education, menopausal/disease/treatment status, hormonal therapy use) were dichotomized for analyses. Mean differences were calculated in outcome measures at baseline and 6-month follow-up as the final endpoint, along with standard deviations and the effect size (mean difference/SD of the differences). Per convention, effect sizes were classified as small (.20), medium (.50), and large (.80) [25]. Clinician communication outcomes were examined descriptively by comparing the proportions of clinic visits in which the behaviors occurred at post-intervention versus baseline. Additionally, we conducted exploratory analyses on the communication variables where the effect post-intervention was evaluated using generalized linear models with robust standard errors via Generalized Estimating Equations to account for within-provider correlation. Specifically, logistic regression was used to examine binary outcomes, Poisson regression was used to examine length of discussion about sexual health and a risk ratio presented for this variable (no discussion was coded as zero seconds), and ordinal logistic regression was used to examine intervention effects on complexity of communication (categorized as 0, 1, or 2) and on patient satisfaction. To provide preliminary estimates of potential benefits, we present the model based estimates of effect sizes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. As the study was not powered for formal comparisons, we did not conduct statistical tests [26, 27].

Results

Clinician Characteristics

The characteristics of the clinician sample have been described elsewhere in greater detail [9]. Briefly, the sample of 7 clinicians consisted of 5 medical oncologists, 1 nurse practitioner, and 1 physician assistant. The majority of the clinician sample was white (5/7) and female (4/7). Four clinicians had fewer than 5 years in practice, 1 had 5–10 years, and 2 had > 15 years.

Patient Characteristics

Of the 172 women approached to participate, one was ineligible (non-English speaking) and 34 refused, leaving 137 patients who consented (acceptance rate=80%). Patients most commonly refused due to lack of interest (n=14) and not wanting to be recorded (n=11). Three patients’ clinic encounters could not be recorded because they were seen in clinic by non-participating clinicians, leaving a final sample of 134 patients with complete audio recording and self-report data (mean age=58.3; SD=11.1). Overall, the patient sample was predominantly white (85.1%; 4.5% Hispanic/Latina), married/partnered (71.6%), and college graduates (54.5%). Most patients were diagnosed with Stage I-II breast cancer (76.9%; 9.7% Stage III; 13.4 Stage IV) and were post-treatment (M=35.8 months since diagnosis; SD=33.5), but nearly one quarter were on active treatment (22.4%). The majority of patients (91.0%) had curative surgery (67.2% lumpectomy; 32.8% mastectomy). Over half had chemotherapy (55.2%) and/or radiation therapy (66.4%). Three quarters of the patient sample had used hormonal therapy (75.4%) and over half was currently on hormonal therapy or Herceptin (57.5%). On average, patients reported modest levels of sexual concerns (M=1.6; SD=2.9).

Comparisons of Baseline and Post-Intervention Patients

Baseline and post-intervention patients did not differ by age, race, partnered status, education, stage of disease, time since diagnosis, recurrent disease, current chemotherapy or hormonal therapy, or level of sexual concerns, p ≥ .08.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Seven of eight clinicians approached agreed (88%). All 7 clinicians who consented to the study completed the intervention, suggesting intervention feasibility. As shown in Table 1, for most items (69%), ≥ 75% of clinicians rated the intervention highly, meeting the benchmark for intervention acceptability. Scores were highest for ease of participation and overall satisfaction and lowest for likely perceived impact on raising sexual concerns with patients.

Table 1.

Clinicians’ Program Evaluations (Acceptability) at Post-Intervention

| Item | M(SD) | N “Agree”/ “Strongly Agree”(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. It was easy for me to participate. | 4.6(.54) | 7(100) |

| 2. The information was relevant to my practice. | 4.3(.76) | 6(86) |

| 3. Overall, how satisfied were you with this program?† | 4.1(.69) | 6(86) |

| Participating in this program… | ||

| 4. Increased my understanding of common sexual concerns for women with breast cancer. | 4.3(.76) | 6(86) |

| 5. Increased my understanding of women’s sexual response. | 4.3(.76) | 6(86) |

| 6. Will help me to communicate with my breast cancer patients about sexual concerns. | 4.1(.69) | 6(86) |

| 7. Made me more sensitive to the issues of breast cancer patients regarding sexuality. | 4.1(1.2) | 5(71) |

| 8. Increased my awareness of available treatments, resources, and referral sources for patients with sexual/intimacy concerns. | 4.1(.90) | 5(71) |

| 9. Will help me know how to respond when patients raise the subject of sexuality. | 4.0(.82) | 5(71) |

| 10. Will make me more likely to give information to patients about sexual and intimacy-related concerns. | 3.9(.38) | 6(86) |

| 11. Is likely to impact my clinical practice. | 3.9(.38) | 6(86) |

| 12. Will improve the quality of care my patients receive. | 3.9(.38) | 6(86) |

| 13. Will make me more likely to raise the topic of sexuality with my patients. | 3.6(.54) | 4(57) |

Responses to this item ranged from Very Satisfied to Very Dissatisfied; the N and % of responses of “Satisfied” or “Very Satisfied” are presented

Clinician Beliefs about Sexual Health Communication

As shown in Table 2, effect size calculations for baseline to 6-month follow-up differences suggested small increases in clinicians’ self-efficacy (d=.27) and reductions in clinicians’ barriers (d=−.14), and medium to large increases in clinicians’ outcome expectancies for communicating about sexual concerns through participating in iSHARE (d=.69).

Table 2.

Clinician Communication Beliefs Across all Four Assessments and Mean Differences

| Measure [Possible Range] | Baseline M(SD) |

Post- Intervention M(SD) |

1-Month Follow-up M(SD) |

6-Month Follow-up M(SD) |

Baseline to 6-Month Difference M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy [0–10] | 7.76(2.24) | 7.81(1.57) | 7.86(1.40) | 8.19(1.33) | 0.43 |

| Outcome Expectancies [0–10] | 7.57(1.76) | 7.80(.68) | 7.91(1.24) | 8.29(1.20) | 0.71 |

| Communication Barriers [1–5] | 2.69(0.55) | 2.56(.61) | 2.78(.38) | 2.61(0.46) | −0.08 |

Clinician Communication

Sexual health was discussed in 61 (46%) of the visits overall: 27 visits at baseline (40%) and 34 visits at post-intervention (51%). As shown in Table 3, the percentage of visits in which the clinician engaged in all communication behaviors increased from baseline to post-intervention. Although the study was not powered to detect pre-post differences in effects, findings for clinician communication behaviors trended toward benefit, showing a small to medium improvement (OR 1.44–3.43). The odds ratio for complexity signifies a 1.65 increase per unit of complexity (from neither asking nor offering, to asking or offering, to both asking and offering) from baseline to post-intervention. The duration of clinic visits did not change from baseline to post-intervention (RR=1.04). Most sexual health discussions lasted under one minute (74%); 8% of discussions lasted 2 minutes or more (data not shown).

Table 3.

Sexual Health Communication in Clinic Visits at Baseline (N=67) and Post-Intervention (N=67)

| Baseline N(%) |

Post- Intervention N(%) |

Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician Communication | |||

| Asking/Offering Information About Sexual Health | |||

| Asked about Sexual Health | 22(33) | 30(45) | 1.66(0.68, 4.05) |

| Offered Information about Sexual Health | 12(18) | 16(24) | 1.44(0.52, 3.98) |

| Complexity in Asking/Offering Information | 1.65(0.68, 4.02) | ||

| Neither Asked Nor Offered Information | 43(64) | 34(51) | -- |

| Asked or Offered Information | 14(21) | 20(30) | -- |

| Both Asked and Offered Information | 10(15) | 13(19) | -- |

| Raised the Topic of Sexual Health | 19(28) | 32(48) | 2.38(0.95, 5.95) |

| Raised the Topic Using Counseling | 4(21) | 12(38) | 3.43(1.47, 8.03) |

| Duration of Sexual Health Communication, in seconds | M(SD) | M(SD) | Rate Ratio (Confidence Interval) |

| Duration, across all visits | 20.8(45.06) | 21.8(48.50) | 1.04(0.72, 1.51) |

| Duration, across clinic visits with sexual health communication | 51.7(59.1) | 42.9(61.4) | -- |

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction scores were uniformly high (low scores indicate high satisfaction on this measure) across both time points (M=1.08; SD=.27), and did not change significantly from baseline (M=1.08, SD=.29) to post-intervention (M=1.07; SD=.25), t (132) = .16, p=.87.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggested that the iSHARE intervention was feasible to implement and generally well-received by clinicians. In addition, though preliminary, the intervention showed promising effects on breast cancer clinicians’ beliefs with respect to sexual health, particularly for clinicians’ self-reported cognitive expectancies. This finding suggests that the iSHARE intervention may have positive effects on the extent to which breast cancer clinicians believe that discussing sexual concerns with their patients will lead to positive outcomes. Cancer clinicians are often reluctant to raise sexual health clinically if they believe the discussion will not be received positively by patients or lead to desired endpoints (e.g., successful treatments) [11], lending importance to this finding.

With regard to the outcome of increasing clinician communication about sexual health, findings suggested that the iSHARE intervention showed promising trends while also raising questions. For instance, asking about sexual health and raising sexual health during clinic visits increased by 12 and 20 percentage points from baseline to post-intervention, respectively. In addition, an exploratory analysis suggested that clinicians seemed to integrate counseling (e.g., normalizing statements) when raising the topic more commonly in clinic visits after as compared to prior to the iSHARE intervention, which is generally recommended in guidelines for clinical discussions of sexual health [28, 29]. Yet, around half of the clinic visits still did not have sexual health communication after the intervention, suggesting even more room for improvement. In particular, these findings raise important questions about what the optimal baseline rate of these communication behaviors should be in the context of different patient needs and competing clinical priorities. This study focused on whether the communication occurred, rather than whether it occurred in relation to a clear need, which should be investigated in future work.

Patients’ satisfaction with their clinicians’ care, including with their communication, remained stably high from baseline to post-intervention. Patients’ satisfaction scores were skewed, with nearly all patients reporting themselves to be highly satisfied. With such high baseline satisfaction, it would be difficult to detect an intervention effect. Moreover, patient satisfaction does not always increase even when clinicians’ skills improve through communication interventions [30]. The satisfaction items may not have captured patients’ satisfaction with their clinicians’ skills of discussing sexual health specifically, which should be done in future studies. Patients may not have expected to have clinical communication about sexual health, and thus may not have reported themselves as dissatisfied if this communication was absent. Increasing patients’ awareness about sexuality could give patients permission to discuss it and thereby expect to discuss this topic with their clinicians. The patients were being treated at a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center; satisfaction scores may differ in other settings.

Study Limitations

As one of the first studies to assess effects of a sexual health communication intervention for breast cancer clinicians, this study had several strengths including use of both self-report and audio recorded dialogue as outcome measures and assessing change over 6 months. Yet in addition to the positive effects seen for the iSHARE intervention, challenges also emerged. For instance, not all clinicians rated the intervention highly on every evaluation item and the intervention did not benefit clinicians’ perceived barriers to communication as much as other beliefs. In an effort to maximize feasibility, the iSHARE intervention was designed to be brief and focused. It is possible that a longer, more in-depth training could enhance acceptability ratings or effects on outcomes, yet this approach may also create challenges for enrolling or retaining practicing clinicians and needs to be tested. Other next steps could include adding convenient, low-intensity modules, such as an educational podcast for continuing education credits, which could address motivational and time barriers to training while enriching content. Additional limitations include the lack of a control condition and the small number of clinician participants. In addition, we did not assess intervention effects on patients’ sexual health outcomes and this should be done in future studies. Future research could also test how baseline levels of self-efficacy or outcome expectancies influence the intervention’s efficacy.

Clinical Implications

Despite these limitations, the study findings have implications for clinical practice. For example, findings suggest that a sexual health communication intervention could have effects on clinicians’ communication during routine clinical encounters, making the intervention directly relevant to practice. In addition, lack of time is a major perceived barrier to breast cancer clinicians in raising the topic of sexual concerns [9, 12], and the findings of this study suggested that including discussions of sexual health did not significantly add time to the clinic visits. Whether longer discussions lead to better patient satisfaction or sexual health outcomes will need to be assessed in future research. Moreover, increases in sexual health communication were not accompanied by decreases in patients’ satisfaction, suggesting that clinicians need not worry that discussing sexual health will be off-putting to patients. Finally, research has shown that worse sexual problems are associated with worse psychological distress for breast cancer survivors [31, 32], and that addressing their sexual concerns may reduce psychological distress [33, 34]. Future studies could investigate whether a sexual health communication intervention improves not only patient sexual health and function but also psychological outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Jennifer B. Reese, PhD was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant (MRSG-14–031-CPPB) from the American Cancer Society and by P30CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. This work has not been previously published or submitted.

References

- 1.Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M et al. Cancer and Sexual Problems. J Sex Med 2010; 7:349–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaelin C, Avis NE. Sexual Problems in Younger Women After Breast Cancer Surgery. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:2815–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L et al. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21:4184–4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boquiren VM, Esplen MJ, Wong J et al. Sexual functioning in breast cancer survivors experiencing body image disturbance. Psychooncology 2016; 25:66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denlinger CS, Sanft T, Baker KS et al. Survivorship, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017; 15:1140–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL et al. Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017; 36:492–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sporn NJ, Smith KB, Pirl WF et al. Sexual health communication between cancer survivors and providers: how frequently does it occur and which providers are preferred? Psychooncology 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reese JB, Sorice K, Beach MC et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2017; 11:175–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese JB, Sorice K, Lepore SJ et al. Patient-Clinician Communication about Sexual Health in Breast Cancer: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Clinic Dialogue. Patient Educ Couns In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seav SM, Dominick SA, Stepanyuk B et al. Management of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Women’s Midlife Health 2015; 1:1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reese JB, Bober SL, Daly MB. Talking about Women’s Sexual Health after Cancer: Why Is It So Hard to Move the Needle? Cancer 2017; 123:4757–4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reese JB, Beach MC, Smith KC et al. Effective Patient-Provider Communication about Sexual Concerns in Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25:3199–3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hordern A, Grainger M, Hegarty S et al. Discussing sexuality in the clinical setting: The impact of a brief training program for oncology health professionals to enhance communication about sexuality. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009; 5:270–277. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang LY, Pierdomenico A, Lefkowitz A, Brandt R. Female Sexual Health Training for Oncology Providers: New Applications. Sexual medicine 2015; 3:189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982; 5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graves KD. Social cognitive theory and cancer patients’ quality of life: a meta-analysis of psychosocial intervention components. Health Psychol 2003; 22:210–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annon J The PLISSIT Model. J Sex Educ Ther 1976; 2:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies AR, Ware JE. GHAA’s Consumer Satisfaction Survey and User’s Manual. Washington, DC: GHAA; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abernethy AP, Zafar SY, Uronis H et al. Validation of the Patient Care Monitor (version 2.0): a review of systems assessment instrument for cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 40:545–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abernethy A, Ahmad A, Zafar S et al. Electronic patient-reported data capture as a foundation of rapid learning cancer care. Med Care 2010; 48:S32–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reese JB, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ et al. Sexual concerns in cancer patients: a comparison of GI and breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18:1179–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reese JB, Porter LS, Casale KE et al. Adapting a couple-based intimacy enhancement intervention to breast cancer: A developmental study. Health Psychol 2016; 35:1085–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales In Pajares F, Urdan T (eds): Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, Edition Greenwich, CT: IAP-Information Age Publishing Inc; 2006; 307–338. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 2011; 45:626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2004; 10:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual Health Communication During Cancer Care: Barriers and Recommendations. Cancer J 2009; 15:74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L et al. How to ask and what to do: a guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care 2016; 10:44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bredart A, Dolbeault S, Savignoni A et al. Prevalence and associated factors of sexual problems after early-stage breast cancer treatment: results of a French exploratory survey. Psychooncology 2011; 20:841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang SB et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2006; 15:579–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reese JB, Smith KC, Handorf E et al. A Randomized Pilot Trial of a Couple-Based Telephone Intervention Addressing Sexual Concerns for Breast Cancer Survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalaitzi C, Papadopoulos V, Michas K et al. Combined brief psychosexual intervention after mastectomy: Effects on sexuality, body image, and psychological well-being. J Surg Oncol 2007; 96:235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.