Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate spectacle adherence with impact resistant lenses among 4-year-old children after unilateral cataract surgery in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

Design:

Retrospective cohort analysis of randomized clinical trial data.

Methods:

Setting:

Multicenter.

Patients:

114 children randomized to contact lens correction or intraocular lens implantation following unilateral cataract surgery during infancy.

Intervention:

One week diaries completed annually and retrospective telephone interviews conducted every 3 months to age 5 years to assess spectacle adherence with impact resistant lenses using. Visual acuity was assessed by a traveling examiner at age 4.5 years.

Main Outcome Measures:

Spectacle adherence between ages 4 to 5 years.

Results:

Children with 20/40 or better vision in their treated eye were more likely to wear spectacles ≥80% of their waking hours than children with vision worse than 20/40 (66% vs 42%, p=0.034). Reported adherence to spectacle wear correlated with reported patching (r=0.30, p=0.002). Spectacle adherence did not correlate with gender, type of healthcare insurance or the refractive error in the treated or fellow eye. Seven patients with reduced vision in their treated eye reported <10% spectacle adherence.

Conclusions:

These results confirm that it is possible to achieve high levels of spectacle adherence among 4-year-old children after unilateral cataract surgery during infancy. However, children with vision worse than 20/40 in their worse eye, who needed eye protection the most, had the worst adherence.

Introduction

It has been recommended that children with visual acuity worse than 20/40 in one eye wear protective eyewear during all of their waking hours because of their increased risk of injurying their fellow eye.1 Patients with reduced visual acuity in one eye are often referred to as “functionally one-eyed” since a loss of vision in their better seeing eye would likely result in a significant change in their lifestyle. Visual acuity worse than 20/40 in one eye is often used as the criteria for functionally one eyed since all but 3 states require best corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better in at least one eye to qualify for an unrestricted driver’s license.2,3 Wearing protective eyewear is particularly important for functionally one eyed children because their reduced motor skills and impaired ability to detect danger increases their risk of ocular trauma.4 Rahi and coworkers5 have reported that an ocular injury is the most frequent cause of vision loss in the normal eye of children with unilateral amblyopia. Traumatic eye injuries are particularly common among boys.6,7

Most children who undergo unilateral cataract surgery during infancy have reduced visual acuity in their treated eye and therefore are functionally one-eyed.8,9 In the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS), 73% of children had a visual acuity worse than 20/40 in their aphakic/pseudophakic eye at age 4.5 years.10 Spectacles are typically prescribed after unilateral congenital cataract surgery by age 2 years to protect both eyes and focus the treated eye. It is recommended that these spectacles have impact resistant lenses. Several studies have evaluated adherence with protective eyewear in monocular children after unilateral enucleation and have reported that about one-half of these children wear spectacles for most of their waking hours, but we are unaware of any studies that have evaluated spectacle adherence after unilateral congenital cataract surgery.1,11

Methods

The overall design of the IATS has been reported previously.12 The IATS is a multicenter randomized clinical trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00212134) comparing intraocular lens (IOL) and contact lens treatment after unilateral congenital cataract surgery in children 6 months of age or younger. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions, in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian of all patients before randomization.

Infants randomized to the contact lens group were fitted with either a silicone elastomer (Silsoft Super Plus; Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) or a gas permeable (X-cel Specialty Contacts, Duluth, GA) lens. Children in both treatment groups were prescribed an overcorrection for their treated eye using spectacles with polycarbonate lenses with a straight top bifocal with a +3.00 D add. The unoperated fellow eye was corrected with spectacles based on the cycloplegic refraction reduced by 1 D if one of the following conditions existed: 1) hyperopia > 5.00 D; 2) myopia > 5.00 D; or 3) astigmatism > 1.50 D. Otherwise, the fellow eye was prescribed a plano lens.

Assessing Spectacle and Occlusion Adherence:

Spectacle wear, contact lens wear and occlusion adherence was assessed using annual diaries and quarterly 48-hour telephone-administered interviews of the caregivers that elicited the same information as the diaries. Diaries were completed by a caregiver over a seven day prospective period. Diaries were completed two months after surgery and at 13, 25, 37 and 49 months of age. The diary was mailed to the caregiver. A staff member called the caregiver after mailing the diary to ensure that the diary had been received and to remind the caregiver to complete the diary.13 The caregiver returned the diary to the Data Coordinating Center following completion. Adherence interviews were performed approximately every 3 months starting 3 months after surgery. The timing of the interview was determined using an algorithm that distributed the preferred day of the call evenly throughout the week. The interview was a semi-structured telephone interview conducted in the primary caregiver’s preferred language (English, Spanish, Portuguese) by study staff at the Data Coordinating Center to minimize any concerns that the caregiver might have about confidentiality of the interview and to ensure that the clinical staff were masked to adherence reported during the interview. For each family, the staff member who interviewed the caregiver was the same across the entire study; More than 90% of all interviews were conducted by a single, English-speaking interviewer. Both the interviews and diaries were designed to gain information about the proportion of time that the child wore spectacles. The structure of the interviews elicited information about the child’s activities, sleep and wake times, meal times and bath times as anchors to improve recall. The reliability and validity of this methodology for assessing adherence to patching have previously been described.14 For the current analyses we only included children in the analysis whose caregiver completed at least one recall interview between ages 4 to 5 years or the 49 month diary.

Visual Acuity Assessment

Monocular optotype acuity was assessed at 4.5 years of age by a masked traveling examiner using the Amblyopia Treatment Study-HOTV test.15 Patients were tested wearing their best correction which had been updated at their last study visit three months earlier. Visual acuity was tested first in the aphakic/pseudophakic eye.

Cycloplegic refraction

A cycloplegic refraction was performed on patients at the age 5.0 year examination. It was performed using either retinoscopy or autorefraction after obtaining cycloplegia with 1% cyclopentolate. For children in the contact lens group, the refraction was performed while the child was wearing their contact lens correction to determine the residual refractive error. eye not being tested was occluded.

Statistical Analysis:

Spectacle and contact lens adherence was calculated by averaging the percent of waking hours in glasses reported on the 49 month of age diary and all 48 hour recall interviews between ages 48 to 60 months. Since visual acuity was only tested by a traveling examiner at age 4.5 years, we elected to only analyze spectacle wear and occlusion therapy for children between ages 48 to 60 months. Stacked cumulative bar charts were used to describe the distribution of spectacle adherence versus both treatments and visual acuity categorized as 20/40 or better and worse than 20/40. Scatterplots were used to show the changes over time in spectacle adherence within subjects. Chi-squared tests were used to compare spectacle adherence categorized as <80% versus ≥80% of waking hours to treatment, visual acuity categorized as above, gender, and insurance (as a surrogate for socioeconomic status). Scatterplots and Pearson correlation were used to correlate spectacle wear and patching. A paired t-test was used to compare contact lens and spectacle adherence in the contact lens group. Analysis of variance was used to descibe the sources of variabilty in spectacle wear over time. The standard deviation of the percent waking hours in glasses from the 49 month of age diary and all 48 hour recall interviews from ages four to five years was calculated. This was compared to visual acuity using an independent group t-test. Boxplots were used to describe spectacle adherence to refraction categorized as hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism and near emmetropia in the treated and fellow eyes. For these analyses a visually significant refractive error was defined as: astigmatism >1.5 D, hyperopia >1 D or myopia >3D. Statistical significance was set a p<0.05.

Results:

A total of 114 children were enrolled in the IATS (eFigure). One child was lost to follow-up at 15 months of age and was excluded from the analysis. One additional child was developmentally delayed and unable to complete the optotype visual acuity assessment at age 4.5 years. A median of 4 assessments (range, 1–5) were available for 101 patients between ages 4 to 5 years. The age 49 month diary was completed for 60% of patients. The remaining assessments were telephone interviews. Spectacle adherence data were available for the remaining 12 patients at younger ages, but were not included in the analyses.

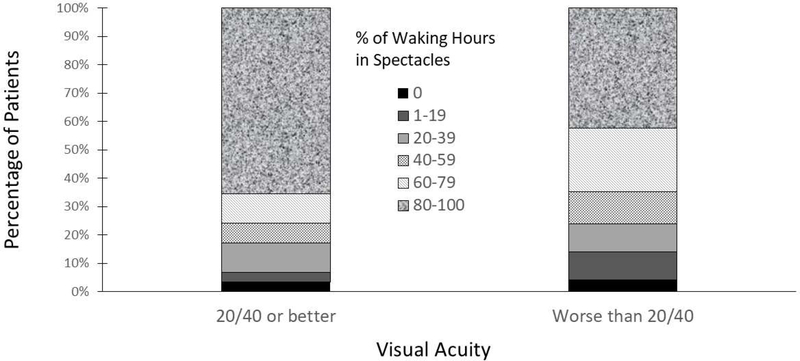

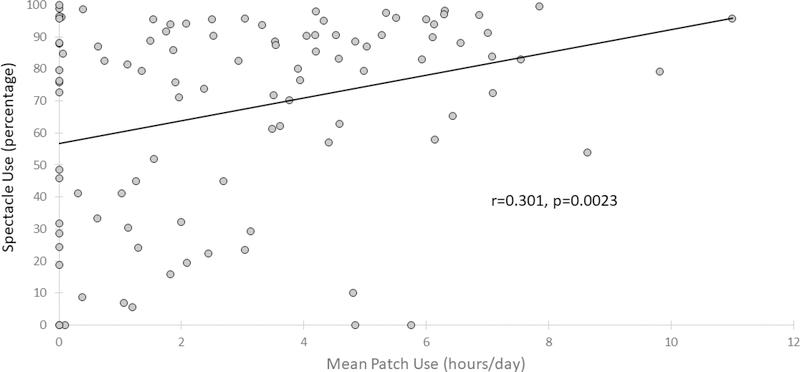

Median spectacle adherence was 80% (IQR, 45%−91%). A greater proportion of children with 20/40 or better vision reported wearing spectacles at least 80% of their waking hours than children with vision worse than 20/40 (65% vs 42%, p=0.034) (Figure 1). In addition, reported adherence to spectacle wear correlated with reported patching (r=0.30, p=0.002) (Figure 2). The percentage of children for whom spectacles were reportedly worn at least 80% of waking hours was similar in girls and boys (girls, 56%; boys, 44%; p=0.76), in children with private vs. public insurance (private insurance, 53%; public insurance, 43%; p=0.34) and in children randomized to receive an IOL or to remain aphakic and to wear a contact lens (IOL group, 54%; contact lens group, 44%; p=0.27) (Figure 3). Contact lens adherence for children in the contact lens group was 15.7% ± 38.4% (p=0.0057) better than spectacle adherence.

Figure 1.

Stacked cumulative bar charts showing the distribution of reported percent of mean spectacle use between ages 4 to 5 years versus visual acuity categorized as 20/40 or better and worse than 20/40.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot showing the Pearson correlation between reported percent of mean spectacle use and reported mean hours of daily patching between ages 4 to 5 years.

Figure 3.

Stacked cumulative bar charts showing the distribution of reported percent of mean spectacle use between the ages 4 to 5 years versus treatment with intraocular lenses (IOL) or contact lenses (CL).

We were interested in determining whether children with large uncorrected refractive errors in either the treated and/or the fellow eye were more likely to be adherent with spectacle wear. There were 63 treated eyes with visually significant refractive errors. In the IOL group the most common of these refractive errors was myopia (n=22) and in the contact lens group, the most common of these refractive errrors was hyperopia >1.0 D (n=15). Only 19 fellow eyes had a refractive error that exceeded the parameters for prescribing a lens other than a plano lens. The most common of these refractive errors was astigmatism >1.5 D (n=15). Neither the refractive error in the treated nor in the fellow eye correlated with spectacle adherence (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Reported percent of waking hours spent wearing spectacles by age in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study based on the uncorrected refractive error in the treated eye.

Figure 5.

Reported percent of waking hours spent wearing spectacles by age in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study based on the refractive error in the untreated eye.

Most patients reported similar levels of spectacle adherences at each assessment, but some patients reported large differences in spectacle use at different assessments. Given this variation, we wanted to be sure that the average spectacle use we report was unaffected by day-to-day differences in reported use and/or by differences in the number of adherence assessments. We found that 80% of the variability in reported adherence was related to variation in spectacle use between patients (Table 1). The mean standard deviation of spectacle use was 7.6 among patients with 20/40 or better vision compared to 12.6 among patients with vision worse than 20/40 (p=0.061).

Table 1.

Variability of Reported Spectacle Adherence

| Source | Variance | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1137 | 100% |

| Subjects | 904 | 80% |

| Changes over time | 233 | 20% |

The overall variance in the n=393 measurements collected was 1137 (or a standard deviation = 33.7).

80% of this variance (904, sd=30.1) is due to differences between subjects.

20% of this variance (233, sd=14.3) is due to changes over time within subjects.

Four patients reported no spectacle adherence between ages 4 to 5 years (mean assessments, 3.7; range, 2–5). One of these patients was in the IOL group; his uncorrected vision was 20/20 in his fellow eye and 20/25 in his pseudophakic eye. The other 3 patients (IOL group, n=1; contact lens group, n=2) had severely reduced best corrected vision in their treated eye (worse than 20/500, n=2; 20/160, n=1). In addition, 4 other patients reported <10% spectacle adherence. All of these patients had best corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse in their treated eye. Two were in the IOL group and 2 were in the contact lens group. There were 18 patients who had no occlusion therapy, but only two of these patients reported no spectacle wear.

Discussion:

We chose to analyze spectacle adherence on the basis of adherence better or worse than 80% for several reasons. First, 80% adherence was the median in our cohort and given the skewed distribution of our data it was preferable to use the median rather than the mean for our analyses. Second, to achieve 80% spectacle adherence a child would have to wear spectacles for most of their waking hours. Given the unpredictability of ocular injuries we believe it is important that protective eye wear be worn for nearly all waking hours for children in this age group rather than only for high risk activities such as sports. Finally, Birch et al16 defined good spectacle adherence in a cohort of children after unilateral congenital cataract surgery as spectacle wear for >75% of waking hours and excellent adherence as spectacle wear >95% of warking hours. Since only 17% of patients in the IATS reported >95% spectacle adherence, it would have been difficult to perform analyses using this criteria for excellent adherence.

Spectacle adherence in the IATS was similar to the adherence reported in several studies of one eyed children. Drack and coworkers1 evaluated spectacles with polycarbonate lenses adherence in 33 children after unilateral enucleation. Adherence was assessed by a telephone interview with a parent and in some cases older children at a mean age of 13 years. Interviews focused on assessing when spectacles were first worn, the percentage of time they were worn, whether they were worn when playing sports and whether they had prevented an injury to the remaining eye. Median spectacle adherence was 80%. Only 3 (11%) children reported wearing their spectacles <10% of their waking hours. Adherence was better among children who were prescribed spectacles at age 3 years or younger. Nearly one-half of the patients reported that their spectacles had prevented their remaining eye from being injured. Neimkin and Custer11 performed a chart review of 132 patients, including 25 children or young adults, who underwent unilateral enucleation. Regular use of spectacles was noted for 55% of children and young adults and was more common among patients who were wearing spectacles prior to enucleation and among patients who returned more often for follow-up. Neither patient age or gender correlated with reported spectacle use. The reasons cited by patients for not wearing spectacles included: good uncorrected vision, concerns about aesthetics, convenience and lack of concern about their remaining eye being injured. The IATS differed from these studies in that none of the patients in the IATS underwent enucleation. Thus patients in the IATS not only wore spectacles for eye protection, but in most cases to correct refractive errors in their treated and less commonly their fellow eyes. The frequent assessment of spectacle adherence in the IATS may have improved adherence. In addition, the ability of caregivers to replace lost spectacles at no charge may have improved adherence. This may also partially explain why spectacle adherence was similar for children with private insurance and public insurance. The cosmesis of a unilateral bifocal may have adversely affected spectacle adherence in the IATS, but this seems unlikely in these young children.

We found that children with 20/40 or better best-corrected vision in their treated eye were more adherent with spectacle wear than children with vision worse than 20/40. There are several possible reasons for this. First, children with good vision in their treated eye were more likely to experience a visual benefit from wearing spectacles. Horwood17 evaluated spectacle adherence in a cohort of young children and found that adherence was highest for children who experienced an improvement in their visual acuity in both eyes and their binocularity with spectacle wear. One-half of the children in the IATS with 20/40 or better vision had measurable stereopsis whereas stereopsis was rare in children with vision worse than 20/40.18,19 Second, children with better vision in their treated eye may be more adherent with treatment regimens in general. We have previously reported an association between good patching adherence and better visual acuity in the treated eye.20 Similarly, in this study we found a correlation between good patching and spectacle adherence.

We expected to find better spectacle adherence among patients with unilateral pseudophakia compared to patients with unilateral aphakia since pseudophakic eyes often had large uncorrected refractive errors whereas aphakic eyes usually had their refractive error fully corrected with a contact lens.21 Furthermore, children randomized to receive an IOL at the time of cataract extraction were prescribed spectacles soon afterwards to correct their residual refractive error whereas children in the contact lens group generally were not prescribed spectacles until age 2 years. We hypothesized that the earlier experience with spectacle use in the IOL group would result in better adherence at age 4 to 5 years. However, this was not the case. Instead, spectacle adherence was similar in both treatment groups. A possible explanation for this outcome is that in both treatment groups the fellow eye had better visual acuity than the treated eye, so children in both treatment groups may not have perceived any visual benefit from wearing spectacles to correct the refractive error in the treated eye.10 Some previous studies have reported better spectacle adherence in boys than girls.22 We did not find a gender difference in spectacle adherence in our study.

We also found that contact lens adherence was better than spectacle adherence for children in the contact lens group wearing both types of correction. This may be because parents perceived wearing the contact lens as more important than wearing spectacles since there was a larger refractive correction in the contact lenses. Perhaps parents didn’t appreciate the importance of their child wearing protective eyewear. Contact lens adherence may have also been better because a contact lens is more difficult to remove for a 4 year old child than spectacles. Finally, wearing spectacles may appear as an immediately obvious “disability” and therefore is a deterrent to their use in this age group.

There are a number of limitations to our study. First, we did not directly measure spectacle adherence but relied on recall interviews and diaries. While, Maconachie et al23 reported a high correlation in adults between spectacle adherence measured objectively using glasses dose monitors and spectacle adherence diaries, we are unaware of any studies that have evaluated this correlation in children. Second, we did not have spectacle adherence data for 13 patients between the ages of 4 to 5 years. Since spectacle adherence was worse for these children at younger ages, it is likely that if adherence data would have been available for them between ages 4 to 5 years, median spectacle adherence would have been lower for the larger group. Third, we only had a median of 4 spectacle adherence data points between ages 4 to 5 years.13 Finally our findings may not be an accurate reflection of spectacle adherence for these children as they become older and enter school and become more self-conscious about wearing glasses. However, given that spectacle wear is particularly important for young children who are at risk of developing amblyopia we felt that this was an important age to evaluate spectacle adherence.

Conclusions:

Spectacle adherence was good for most four-year-olds in the IATS after unilateral cataract surgery during infancy. However, spectacle adherence was worse for the group of children who needed eye protection the most, functionally one eyed children. Clinicians caring for children who have undergone unilateral cataract surgery should encourage them to wear spectacles with impact resistant lenses during all of their waking hours to optimize their visual function and also for eye protection particularily during their preschool years when they are at increased risk of ocular injury.

Supplementary Material

Consort diagram for the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.

Highlights.

Children with good vision in their treated eye had better spectacles adherence.

Adherence to spectacle wear correlated with reported patching.

Seven children with reduced vision in their treated eye had <10% spectacle adherence.

Acknowledgments:

a. Funding/Support: Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants U10 EY13272, U10 EY013287, UG1 EY013272, 1UG1 EY025553, P30 EY026877 and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, New York

b. Financial Disclosures: Scott R Lambert: Consultant, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics and Kala Pharmaceuticals; the following authors have no financial disclosures: Lindreth DuBois, George Cotsonis, E. Eugenie Hartmann, Carolyn Drews-Botsch. All authors meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Biography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Drack A, Kutschke PJ, Stair S, Scott WE. Compliance with safety glasses wear in monocular children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30(4):249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinkuller PG. Legal vision requirements for drivers in the United States. Virtual Mentor. 2010;12(12):938–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Protective eyewear for young athletes. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and American Academy of Ophthalmology Committee on Eye Safety and Sports Ophthalmology. Pediatrics. 1996;98(2 Pt 1):311–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celano M, Hartmann EE, DuBois LG, Drews-Botsch C, Infant Aphakia Treatment Study G. Motor skills of children with unilateral visual impairment in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(2):154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahi J, Logan S, Timms C, Russell-Eggitt I, Taylor D. Risk, causes, and outcomes of visual impairment after loss of vision in the non-amblyopic eye: a population-based study. Lancet. 2002;360(9333):597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grin TR, Nelson LB, Jeffers JB. Eye injuries in childhood. Pediatrics. 1987;80(1):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klopfer J, Tielsch JM, Vitale S, See LC, Canner JK. Ocular trauma in the United States. Eye injuries resulting in hospitalization, 1984 through 1987. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(6):838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birch EE, Swanson WH, Stager DR, Woody M, Everett M. Outcome after very early treatment of dense congenital unilateral cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(13):3687–3699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Autrata R, Rehurek J, Vodickova K. Visual results after primary intraocular lens implantation or contact lens correction for aphakia in the first year of age. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219(2):72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Infant Aphakia Treatment Study G, Lambert SR, Lynn MJ, et al. Comparison of contact lens and intraocular lens correction of monocular aphakia during infancy: a randomized clinical trial of HOTV optotype acuity at age 4.5 years and clinical findings at age 5 years. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(6):676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neimkin MG, Custer PL. Compliance With Protective Lens Wear in Anophthalmic Patients. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(1):61–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Drews-Botsch C, et al. The infant aphakia treatment study: design and clinical measures at enrollment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drews-Botsch C, Cotsonis G, Celano M, Lambert SR. Assessment of Adherence to Visual Correction and Occlusion Therapy in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2016;3:158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drews-Botsch CD, Celano M, Kruger S, Hartmann EE. Adherence to occlusion therapy in the first six months of follow-up and visual acuity among participants in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(7):3368–3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moke PS, Turpin AH, Beck RW, et al. Computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the amblyopia treatment study visual acuity testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(6):903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birch EE, Stager DR. The critical period for surgical treatment of dense congenital unilateral cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(8):1532–1538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horwood AM. Compliance with first time spectacle wear in children under eight years of age. Eye (Lond). 1998;12 ( Pt 2):173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambert SR, DuBois L, Cotsonis G, Hartmann EE, Drews-Botsch C. Factors associated with stereopsis and a good visual acuity outcome among children in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(9):1221–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann EE, Stout AU, Lynn MJ, et al. Stereopsis results at 4.5 years of age in the infant aphakia treatment study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(1):64–70 e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drews C, Celano M, Cotsonis G, Hartmann EE, Lambert SR. The relationship between occlusion therapy and optotype visual acuity at 4 ½ years using data from a randomized clinical trial, the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weakley DR Jr., Lynn MJ, Dubois L, et al. Myopic Shift 5 Years after Intraocular Lens Implantation in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(6):822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matter KC, Sinclair SA, Xiang H. Use of protective eyewear in U.S. children: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maconachie GD, Farooq S, Bush G, Kempton J, Proudlock FA, Gottlob I. Association Between Adherence to Glasses Wearing During Amblyopia Treatment and Improvement in Visual Acuity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(12):1347–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Consort diagram for the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study.