INTRODUCTION

The Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), established with the Affordable Care Act, began reducing payments in 2012 to Medicare-participating hospitals with higher than expected readmission rates for the targeted conditions of heart failure (HF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia (PN). The readmission ratio calculations were adjusted for clinically relevant factors1 and by excluding admissions ending in an against medical advice (AMA) discharge, when a patient leaves the hospital prior to a physician-recommended endpoint. Although the HRRP has reduced readmissions overall,2 there remains the possibility of unintended negative consequences. Given that an AMA discharge designation under the HRRP may have positive financial implications for the hospital, we sought to identify if the HRRP was associated with a change in AMA discharges.

METHODS

We utilized longitudinal data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) available through HCUPnet3 for the years 1993 to 2015. We examined the number and proportion of AMA discharges over time and identified discharges with a principal diagnosis of PN, HF, and AMI using the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, (ICD-9).4 To better characterize the relationship between the HRRP and AMA discharges, we also analyzed AMA discharges in patients with alcohol/drug use and alcohol/drug use-induced mental disorders, a set of conditions not targeted by the HRRP.

RESULTS

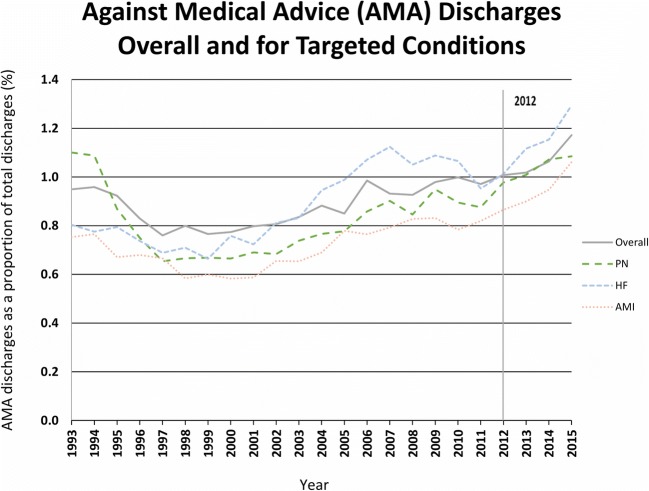

Figure 1 plots AMA discharges as a proportion of total discharges both overall and for the target conditions of PN, AMI, and HF. During the study period of 1993 to 2015, AMA discharges nationally ranged from 0.8 to 1.2% of all discharges, peaking in 2015. The greatest 3-year rate of increase was 18% and 16% during the respective time periods 2003–2006 and 2012–2015. Between 2012 and 2015, AMA discharges increased among the target conditions: PN increased by 11%, HF by 28%, and AMI by 23% and AMA discharges in 2015 for HF and AMI were the highest rates of the study period.

Figure 1.

Against medical advice (AMA) discharges overall and for target conditions.

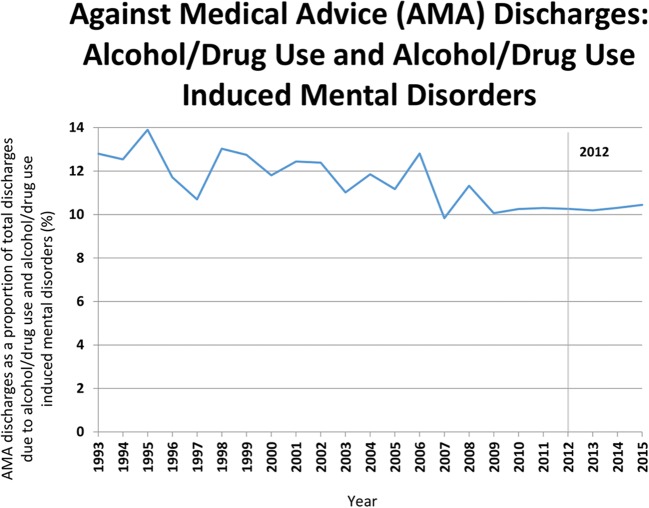

Figure 2 demonstrates the higher average AMA discharge rate in patients with alcohol/drug use or alcohol/drug use-induced mental disorders. Between 2012 and 2015, the AMA discharge rate increased 2% among these conditions.

Figure 2.

Against medical advice (AMA) discharges: alcohol/drug use and alcohol/drug use-induced mental disorders.

DISCUSSION

Nationally, the AMA discharge rate overall, as well as for the HRRP target conditions, rose during most of the study period with the highest rates at the conclusion of the study period. The sharp contrast between AMA discharge rates for HRRP target conditions and non-HRRP target conditions indicates that these rates did not increase uniformly post-2012.

Because AMA discharge rates are affected not just by patient factors, but by hospital and health system factors,5 the HRRP may act along with local factors to influence adverse discharge outcomes. The HRRP’s exclusion of AMA discharges in the calculation of readmission penalties may provide a financial incentive that could affect AMA discharge practices. Although the current results are not sufficient to conclude that there is a clear relationship between the HRRP and rising AMA discharge rates, the potential for such an unintended consequence is deserving of further study.

Maryland, which was exempted from the Medicare inpatient and outpatient Prospective Payment System, may offer guidance for understanding the role of readmission policy on AMA discharges. In 2014, Maryland changed its methodology for its state-based readmission reduction program by switching to include AMA discharges in its readmission calculation.6 This change removes potential financial incentives for hospitals to discharge patients AMA (i.e., any readmission would still be penalized regardless of discharge status), and it may incentivize hospitals to take greater responsibility for the discharge process when patients decline recommended inpatient care. Further research on this state’s discharge practices would inform this issue.

Our study was limited by not considering specific ambulatory care-sensitive conditions which may be sensitive to the HRRP and thus may not have fully characterized the full (i.e., targeted and spillover) effects of the HRRP. Further research expanding the range of variables might help to better characterize the pre-HRRP increase in AMA discharge rates.

AMA discharges are associated with adverse health and health system outcomes, but their rates continue to rise nationally and ended at their highest level in the period we studied. Further research is needed to better characterize the role of non-patient-related factors, including readmission policies, to assess for any potential effect on AMA discharge rates.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services - Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- 2.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543–1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HCUPnet, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- 4.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(2):243–252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onukwugha EC, Shaya FT, Saunders E, Weir MR. Ethnic disparities, hospital quality, and discharges against medical advice among patients with cardiovascular disease. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maryland All-Payer Model Agreement. http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/documents/md-maphs/stkh/MD-All-Payer-Model-Agreement-%28executed%29.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2018.