INTRODUCTION

Burnout has accelerated among practicing physicians and trainees.1 Over half of medical students report burnout, associated with self-reported unprofessional conduct, reduced empathy, and less altruistic values.2 Students need adaptive skills to cope with the stressors of a demanding learning environment. Although building resilience is a priority area for medical education,3 few examples exist of programs engaging students as key partners in building and sustaining wellness over time. We describe a novel, interactive, student-led workshop that introduced participants to two easy-to-use, skills-based resilience tools.

METHODS

A 90-min student-led interactive workshop introduced the concept of “Everyday Resilience” and taught participants two easy-to-use, skills-based tools. Objectives were to: (1) define resilience and discuss its protective role against burnout; (2) learn to apply the tools. Participants were first year students at a large US medical school who elected to participate. First years were targeted to provide them with resilience tools ahead of challenges they might face in the clerkship year.

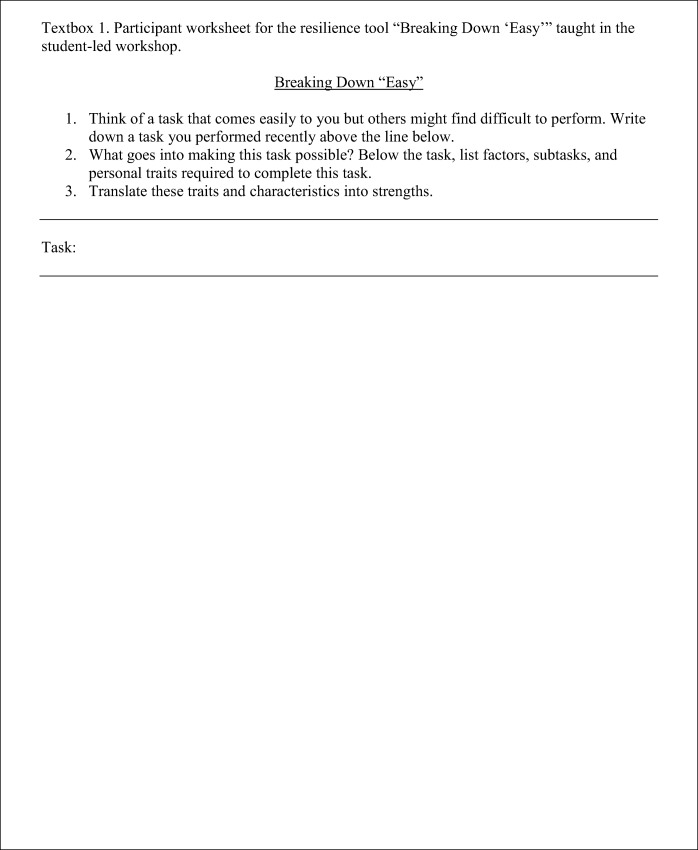

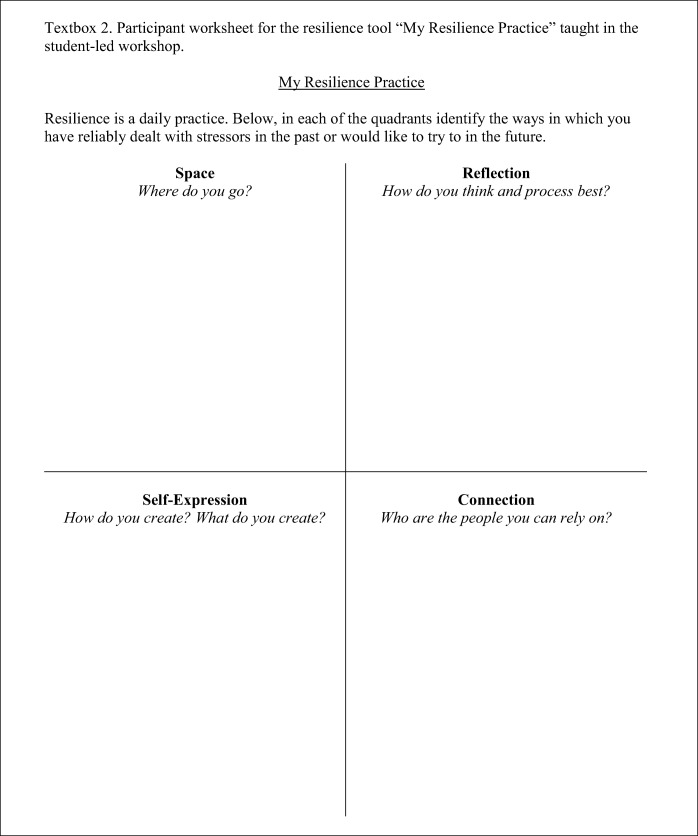

Two complementary tools were introduced during the workshop to help students engage in self-reflection, identify personal strengths, and build active coping skills: “Breaking Down ‘Easy’” (Textbox 1) and “My Resilience Practice” (Textbox 2).

Students completed pre- and post-workshop surveys (adapted from a resilience study in clerkship students4) to assess prior exposure to resilience training and evaluate the quality of the workshop and the tools.

RESULTS

Eighteen students participated in the workshop. Ninety-four percent (17/18) completed pre- and post-session surveys.

Prior to the workshop, 71% (12/17) had “no exposure” or “a little/some exposure” to burnout and resilience training. Ninety-four percent (16/17) did not feel they had sufficient training. Only 65% (11/17) felt able to cope with setbacks and failures. Almost half of the students (47%; 9/17) felt they did not have the skills to manage stress and prevent burnout.

Ninety-four percent (16/17) of participants felt the workshop was “valuable” or “very valuable.”

The tools were considered easy-to-use and a good resource for the future when faced with setbacks or stress. Documenting their resilience plan helped students transform an informal practice into a formal “resilience strategy” or “stress action plan.”

Participants valued opportunities to “pair-share” in small groups prior to large group discussions. The workshop was perceived as a safe space to share experiences and begin a meaningful conversation with peers. Seventy-six percent (13/17) “strongly agreed” that more training in a longitudinal curriculum was necessary.

DISCUSSION

Our pilot demonstrated that first year medical students are eager for resilience training and value practical, easy-to-use, skills-based tools to help them cope with stressors and prevent burnout. A majority felt lacking in such skills and unable to adequately cope with setbacks. Given high levels of stressors faced by clerkship students,4 our intervention targeted pre-clerkship students to equip them with resilience practices ahead of the clinical year.

Our workshop was well received. It was praised for being interactive and creating a safe space for discussion. This pilot is proof-of-concept that our resilience tools are easy-to-teach and use, and that a student-facilitated workshop offers an effective means of introducing medical students to this important topic.

Limitations include the small sample size, limited scope of evaluation, and self-selection of students. As next steps, our intervention will be delivered as a mandatory session for all pre-clinical students during a transitional course preparing students for their clerkship year. This intervention offers an opportunity for a larger-scale longitudinal study. We will measure students’ resilience, burnout, work engagement, and use of resilience tools at quarterly intervals during the clinical year.

A strength of this workshop is that it involves students at its core—as participants and facilitators. Senior students are well placed to understand stressors faced in the learning environment; involving them in the delivery of resilience training may be a novel approach to combat burnout. Future work is necessary to evaluate the impact of this intervention over time, as well as to develop “touch-points” for resilience training throughout the undergraduate curriculum and into graduate medical training.5, 6

Implementing effective programs to build resilience in our future physicians is critical to enhancing well-being and reducing burnout. By cultivating a growth mindset that resilience can be practiced and built—and providing tools to do so—we hope to prepare students for, and inoculate them against, the stressors they will face in their medical careers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Kaarkuzhali Babu Krishnamurthy for her support and encouragement throughout the project, and for reviewing an earlier version of the workshop materials and the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Angela Marsiglio for sharing her expertise in burnout, advising on evaluation of the workshop, and for reviewing the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

The HMS Academy approved this study.

References

- 1.Dyrbye LN, TD Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC; 2017. Accessed September 21, 2018 at https://nam.edu/burnout-among-health-care-professionals-a-call-to-explore-and-address-this-underrecognized-threat-to-safe-high-quality-care/.

- 2.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Eacker A, et al. Relationship Between Burnout and Professional Conduct and Attitudes Among US Medical Students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):301–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Houpy JC, Lee WW, Woodruff JN, Pincavage AT. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med Ed Online. 2017;22(1):1320187. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1320187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howe A, Smajdor A, Stöckl A. Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):349–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. Nurturing resiliency in medical trainees. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]