Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy may be particularly burdensome near the end of life, as patients “accumulate” medications to treat and prevent multiple diseases.

Objective

To evaluate associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life (QOL) in patients with advanced, life-limiting illness (clinician-estimated, 1 month–1 year).

Design

Secondary analysis of baseline data from a trial of statin discontinuation.

Participants

Adults with advanced, life-limiting illness.

Main Measures

Polypharmacy was assessed by summing the number of non-statin medications taken regularly or as needed. Symptom burden was assessed using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (range 0–90; higher scores indicating greater symptom burden) and QOL was assessed using the McGill QOL Questionnaire (range 0–10; higher scores indicating better QOL). Linear regression models assessed associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and QOL.

Key Results

Among 372 participants, 47% were age 75 or older and 35% were enrolled in hospice. The mean symptom score was 27.0 (standard deviation (SD) 16.1) and the mean QOL score was 7.0 (SD 1.3). The average number of non-statin medications was 11.6 (SD 5.0); one-third of participants took ≥ 14 medications. In adjusted models, higher polypharmacy was associated with higher symptom burden (coefficient 0.81; p < .001) and lower QOL (coefficient − .06; p = .001). Adjusting for symptom burden weakened the association between polypharmacy and QOL (coefficient − .03; p = .045) without a significant interaction, suggesting that worse quality of life associated with polypharmacy may be related to medication-associated symptoms.

Conclusions

Among adults with advanced illness, taking more medications is associated with higher symptom burden and lower QOL. Attention to medication-related symptoms and shared decision-making regarding deprescribing are warranted in this setting.

NIH Trial Registry Number

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier for Parent Study - NCT01415934

Key Words: pharmaceutical care, quality of life, end-of-life care, geriatrics

INTRODUCTION

Polypharmacy, defined by the World Health Organization as “the administration of many drugs at the same time or the administration of an excessive number of drugs,”1 is an increasingly common public health problem. While there is no uniformly accepted definition of the number of medications that constitutes polypharmacy, some studies have defined polypharmacy as ≥ 4 medications2 or ≥ 5 medications.3 Fifteen percent of all adults in the United States use ≥5 prescription drugs.4 Polypharmacy is associated with poor health outcomes, including medication non-adherence, adverse drug effects, and worse quality of life in elderly population- and primary care-based cohorts.5, 6 Polypharmacy is particularly burdensome near the end of life, as patients “accumulate” medications to a treat life-limiting illness and its associated symptoms, prevent age-related diseases, and control non-life-threatening comorbidities.7 In an analysis of medication burden among a cohort of adults with advanced, life-limiting illness, participants took an average of 11.5 (standard deviation (SD) 5) medications, and the most commonly used medications were for primary disease prevention (e.g., anti-hypertensives), not symptom management.8

Patients near the end of life may be receiving medications whose risk is higher than the benefit. First, many of the medications used are for preventing diseases which, given patients’ remaining life expectancies, may never occur. Second, even medications for secondary prevention may be of limited effectiveness given patients’ limited prognoses. Third, many patients have co-morbidities, such as hepatic or renal disease, that increase the risk of medication side effects.9, 10 Finally, patients near the end of life may be on medications with significant side effects, such as anticholinergics. To date, however, associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden and quality of life in patients with life-limiting illness are not well understood.

The goal of this analysis was to evaluate associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life in a large cohort of adult patients with advanced, life-limiting illness. Our hypotheses were that polypharmacy is associated with higher symptom burden and worse quality of life.

METHODS

Overview and Conceptual Framework

This study is a secondary analysis of data from a large, multi-center randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the safety and impact of discontinuing statin medications in patients with advanced, life-limiting illness (clinician estimate of 1 month-1 year). Study design and methods have been published previously11 For this analysis, participants without baseline polypharmacy data were excluded. No prior analysis has examined associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life.

Our conceptual model, based on a work by Marcum et al.,12 posits that polypharmacy leads to higher symptom burden (related to therapeutic failure/medication non-adherence, adverse drug events, and increased medication side effects), and higher symptom burden in turn leads to worse quality of life.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from each site participating in the original study. Exempt approval for use of de-identified data in this analysis was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh IRB.

Sample

Eligible patients were English-speaking adults with a diagnosis of advanced, life-limiting illness. The criteria for determining advanced, life-limiting illness were as follows: (1) physician ‘would not be surprised if the patient died in the next year,‘13, 14; (2) life expectancy of more than 1 month; and (3) recent deterioration in functional status, defined as a reduction in the Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale score to < 80% in the past 3 months.15 Because the original trial examined statin discontinuation, all eligible participants were receiving a statin medication for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease at the time of study enrollment. Participants were enrolled from 15 sites across the USA participating in the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group (PCRC).16

Measures

All measures were collected at baseline. The number of total medications was assessed by documenting the number of non-statin medications either (1) taken regularly; (2) administered as needed on at least 50% of days in the past week; or (3) administered as needed on less than 50% of days in the past week. Medications included all prescriptions (both ongoing and time-limited, e.g., a course of antibiotics) as well as over-the-counter medications intended to relieve symptoms (e.g., NSAIDS). Topical, ophthalmic, and transdermal medications were included, in addition to medications taken orally. Consistent with prior analyses, these three measures were summed to create a measure of total non-statin medications.11

Symptom burden was assessed by administering the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS). This patient-rated scale assesses nine standard symptoms with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (higher scores indicate higher symptom burden, with a symptom ranked 4 or higher representing a moderate or severe symptom).17, 18 Single-symptom scores were summed to create a total ESAS score (range 0–90). The minimal clinically important differences for improvement/deterioration on the total ESAS score are 5.7/2.9.19 If at least half the items were answered, missing values were imputed as the mean of the completed items.

The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire was used to measure quality of life.20 This questionnaire, developed for use in palliative care settings, includes four subscales measuring physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, existential well-being, and support. Means of these four subscales are summed to create a total score (range 0–10), with higher scores indicating better quality of life. If at least half the items of a subscale were answered, the same mean imputation rule was applied to missing responses.

Additional participant characteristics included demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and insurance status), primary diagnosis, Charlson Comorbidity Index score,21 performance status (Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status; range 0–100 with higher scores indicating better performance status),15 and enrollment in hospice.

Statistical Analysis

Because there is no uniformly accepted definition of the number of medications that constitutes polypharmacy,22 we defined polypharmacy groups as low (0–8 medications), medium (9–13 medications), and high (≥ 14 medications) based on distribution of the data. This allowed us to create three groups with roughly even numbers of participants in each group. We used descriptive statistics (percentages; means and standard deviations) to present participant characteristics overall, with chi-square tests or one-way ANOVA tests to assess differences in participant characteristics by polypharmacy group. We used histograms, kernel density plots and Q-Q plots to confirm model assumptions for linear regression. We then ran linear regression models to assess unadjusted and adjusted associations between (1) polypharmacy and symptom burden and (2) polypharmacy and quality of life. For regression models, polypharmacy was included as a continuous variable. Parsimonious final adjusted models included gender, age, primary diagnosis, whether the patient was enrolled in hospice, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status as covariates. We selected these variables for inclusion in adjusted models because they were found to be associated (p < 0.05) with either symptom burden or quality of life in simple regression models and/or are known to be associated with these outcomes.

To test for effects of symptom burden on the association between polypharmacy and quality of life, we ran two additional models examining the association between polypharmacy and quality of life adjusting for (1) symptom burden and (2) the interaction between polypharmacy and symptom burden, along with the other variables included in parsimonious adjusted models.23, 24 This approach allowed us to test (1) whether adjusting for symptom burden weakened the association between polypharmacy and quality of life and (2) whether the interaction between polypharmacy and symptom burden was significant. Finally, we tested whether the effect of adjusting for symptom burden was significant using percentile-based bootstrap25 to evaluate the difference in adjusted coefficients for polypharmacy in models with and without adjustment for symptom burden.

All analyses were conducted in STATA [STATA/SE 15.1 StataCorp, Texas].

RESULTS

Among 381 participants enrolled in the original trial, 372 participants had baseline data on the number of total medications and were included in this analysis. Nearly half (47%) of participants were age 75 or older, the primary diagnosis was cancer for 52% of participants, and one-third of participants were enrolled in hospice at baseline. The most common non-cancer diagnoses were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and dementia. The mean performance status (AKPS) of 54 signifies the need for considerable assistance and frequent medical care. Additional participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics overall and by polypharmacy group

| Polypharmacy group* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 372) | Low (N = 114) | Medium (N = 134) | High (N = 124) | p value† | ||

| Sex | Male | 207 (56) | 61 (54) | 81 (60) | 65 (52) | 0.370 |

| Female | 165 (44) | 53 (46) | 53 (40) | 59 (48) | ||

| Race | White | 307 (83) | 95 (83) | 114 (85) | 98 (79) | 0.538 |

| Black | 54 (15) | 17 (15) | 17 (13) | 20 (16) | ||

| Other | 11 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 6 (5) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 16 (4) | 4 (4) | 5 (4) | 7 (6) | 0.769 |

| Non-Hispanic | 354 (95) | 109 (96) | 128 (96) | 117 (94) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Age | 44–59 | 36 (10) | 9 (8) | 12 (9) | 15 (12) | 0.861 |

| 60–74 | 160 (43) | 49 (43) | 55 (41) | 56 (45) | ||

| 75–89 | 142 (38) | 45 (39) | 53 (40) | 44 (35) | ||

| ≥ 90 | 34 (9) | 11 (10) | 14 (10) | 9 (7) | ||

| Education | < HS Graduate | 51 (14) | 16 (14) | 15 (11) | 20 (16) | 0.479 |

| HS Graduate | 189 (51) | 56 (49) | 78 (58) | 55 (44) | ||

| College Graduate | 128 (34) | 41 (36) | 40 (30) | 47 (38) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | ||

| Insurance | Medicare | 275 (74) | 83 (73) | 100 (75) | 92 (74) | 0.949 |

| Medicaid | 31 (8) | 9 (8) | 11 (8) | 11 (9) | ||

| Private | 42 (11) | 15 (13) | 14 (10) | 13 (10) | ||

| Other | 21 (6) | 7 (6) | 8 (6) | 6 (5) | ||

| Uninsured | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | ||

| Primary DX | Cancer | 193 (52) | 72 (63) | 64 (48) | 57 (46) | 0.015 |

| Non-cancer | 179 (48) | 42 (37) | 70 (52) | 67 (54) | ||

| Enrolled | No | 236 (63) | 77 (68) | 85 (63) | 74 (60) | 0.167 |

| In Hospice | Yes | 132 (35) | 34 (30) | 48 (36) | 50 (40) | |

| Unknown | 4 (1) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Performance status (AKPS)‡ | 53.58 ± 13.09 | 55.00 ± 13.39 | 54.55 ± 12.24 | 51.21 ± 13.47 | 0.046 | |

| Comorbidities (CCI) ‡ | 4.82 ± 2.75 | 4.66 ± 2.75 | 4.99 ± 2.74 | 4.78 ± 2.78 | 0.625 | |

All numbers are N (%) except where indicated otherwise

HS, high school; AKPS, Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status; CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index

*Low polypharmacy = 0–8 medications; medium polypharmacy = 9–13 medications; high polypharmacy = ≥ 14 medications

†Pearson’s chi-square test or one-way ANOVA test

‡Mean ± SD

The average number of non-statin medications taken by all participants was 11.6 (SD 5.0), with a range from 1 to 33. Polypharmacy was low (0–8 medications) for 31% of participants, medium (9–13 medications) for 36%, and high (≥ 14 medications) for 33%. Only 3% of participants took less than 4 medications. Patients with high polypharmacy were more likely to have non-cancer diagnoses and lower mean performance status (see Table 1). There were no other significant differences in participant characteristics by the polypharmacy group (see Table 1).

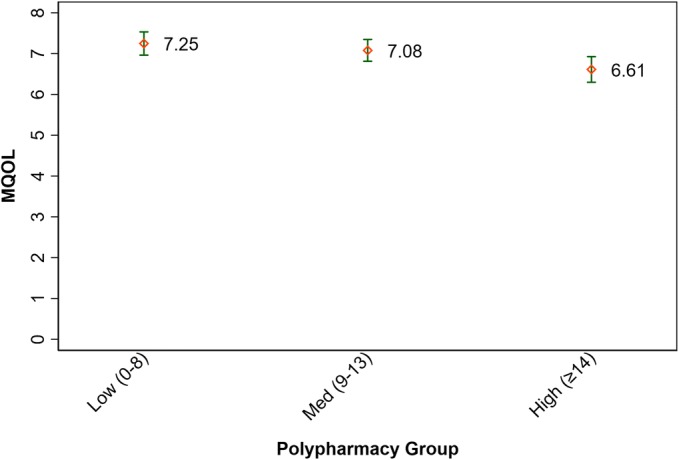

The mean symptom score for all participants was 27.0 (SD 16.1), with higher symptom scores associated with higher polypharmacy (see Fig. 1). The mean total quality of life score was 6.97 (SD 1.32) for all participants, with worse total quality of life associated with higher polypharmacy (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Symptom burden by polypharmacy group. Low polypharmacy = 0–8 medications; medium polypharmacy = 9–13 medications; high polypharmacy = ≥ 14 medications; p value = < 0.001 (anova) 95% confidence intervals; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale.

Fig. 2.

Quality of life by polypharmacy group. Low polypharmacy = 0–8 medications; medium polypharmacy = 9–13 medications; high polypharmacy = ≥ 14 medications; p value = < 0.004 (ANOVA) 95% confidence intervals; MQOL, McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire.

In unadjusted linear regression models, higher polypharmacy was associated with higher symptom burden (see Table 2). This association remained significant (adjusted beta 0.81; p < 0.001) in fully adjusted linear regression models (see Table 2). This implies that each additional medication was associated with a higher symptom burden of 0.81 points on the ESAS. Higher performance status was associated with lower symptom burden and a higher comorbidity index score was associated with higher symptom burden in fully adjusted linear regression models (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between participant characteristics and symptom burden

| Unadjusted beta [95% CI] (N = 284) | p | Adjusted beta [95% CI] (N = 282) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypharmacy | 0.88 [0.50, 1.26] | < .001 | 0.81 [0.43, 1.20] | < .001 | |

| Sex | Male | (Ref.) | |||

| Female | 0.42 [− 3.39, 4.24] | 0.827 | 0.46 [− 3.13, 4.05] | 0.802 | |

| Race | White | (Ref.) | |||

| Black | − 1.31 [− 6.55, 3.93] | 0.624 | |||

| Other | 3.71 [− 6.58, 13.99] | 0.478 | |||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | (Ref.) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | − 3.30 [− 13.54, 6.94] | 0.527 | |||

| Unknown | (Dropped) | ||||

| Age | 44–59 | (Ref.) | |||

| 60–74 | − 2.78 [− 8.73, 3.16] | 0.358 | − 1.09 [− 6.71, 4.53] | 0.704 | |

| 75–89 | − 7.56 [− 13.86, − 1.26] | 0.019 | − 4.82 [− 10.95, 1.32] | 0.123 | |

| ≥ 90 | − 2.83 [− 11.98, 6.31] | 0.543 | 1.02 [− 8.05, 10.09] | 0.824 | |

| Education | < HS graduate | (Ref.) | |||

| HS graduate | − 4.30 [− 10.85, 2.25] | 0.197 | |||

| College Graduate | − 3.10 [− 9.89, 3.68] | 0.369 | |||

| Unknown | (Dropped) | ||||

| Insurance | Medicare | (Ref.) | |||

| Medicaid | 7.07 [− 0.38, 14.52] | 0.063 | |||

| Private | 1.13 [−4.26, 6.51] | 0.681 | |||

| Other | − 1.65 [− 9.46, 6.17] | 0.678 | |||

| Uninsured | − 2.98 [− 25.56, 19.60] | 0.795 | |||

| Primary DX | Cancer | 1.89 [− 1.98, 5.75] | 0.337 | 2.27 [− 1.96, 6.50] | 0.291 |

| Non-cancer | (Ref.) | ||||

| Enrolled | No | (Ref.) | |||

| In hospice | Yes | − 2.04 [− 6.16, 2.08] | 0.331 | − 2.92 [− 7.20, 1.36] | 0.180 |

| Unknown | (Dropped) | ||||

| Performance status (AKPS) | − 0.30 [− 0.45, − 0.15] | < .001 | − 0.26 [− 0.41, − 0.10] | 0.001 | |

| Comorbidities (CCI) | 1.35 [0.68, 2.01] | < .001 | 1.02 [0.34, 1.71] | 0.004 | |

Symptom burden was assessed using the 9-item Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), with 3% of ESAS scores requiring imputed data if at least half but not all items were answered

HS, high school; AKPS, Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index

Similarly, in unadjusted linear regression models, higher polypharmacy was associated with lower quality of life (see Table 3) and this association remained significant (adjusted beta − 0.06; p = 0.001) in adjusted analysis. This implies that every additional medication was associated with lower quality of life by 0.06 points on the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Higher performance status and being enrolled in hospice were associated with higher quality of life in fully adjusted models (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted association between participant characteristics and quality of life

| Unadjusted beta [95% CI] (N = 239) | p | Adjusted beta [95% CI] (N = 238) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypharmacy | − 0.07 [− 0.10, − 0.03] | < .001 | − 0.06 [− 0.09, − 0.02] | 0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | (Ref.) | |||

| Female | − 0.02 [− 0.36, 0.32] | 0.915 | 0.04 [−0.28, 0.37] | 0.791 | |

| Race | White | (Ref.) | |||

| Black | − 0.16 [− 0.66, 0.34] | 0.522 | |||

| Other | − 0.73 [− 1.57, 0.11] | 0.088 | |||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | (Ref.) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 0.42 [−0.42, 1.26] | 0.324 | |||

| Unknown | (Dropped) | ||||

| Age | 44–59 | (Ref.) | |||

| 60–74 | 0.32 [− 0.19, 0.84] | 0.219 | 0.20 [− 0.30, 0.69] | 0.437 | |

| 75–89 | 0.72 [0.16, 1.27] | 0.011 | 0.47 [− 0.07, 1.02] | 0.089 | |

| ≥ 90 | 0.67 [− 0.09, 1.43] | 0.085 | 0.33 [− 0.44, 1.09] | 0.402 | |

| Education | < HS grad. | (Ref.) | |||

| HS grad. | 0.50 [− 0.10, 1.09] | 0.103 | |||

| College graduate | 0.62 [0.00, 1.23] | 0.049 | |||

| Unknown | (Dropped) | ||||

| Insurance | Medicare | (Ref.) | |||

| Medicaid | 0.28 [− 0.42, 0.97] | 0.437 | |||

| Private | − 0.26 [− 0.73, 0.22] | 0.284 | |||

| Other | − 0.32 [− 1.09, 0.45] | 0.417 | |||

| Uninsured | − 2.23 [− 4.83, 0.37] | 0.093 | |||

| Primary DX | Malignant Tumor | − 0.12 [− 0.46, 0.23] | 0.502 | 0.03 [− 0.36, 0.41] | 0.881 |

| Other | (Ref.) | ||||

| Enrolled | No | (Ref.) | |||

| In hospice | Yes | 0.60 [0.25, 0.95] | 0.001 | 0.66 [0.28, 1.04] | 0.001 |

| Unknown | (Dropped) | ||||

| AKPS | 0.02 [0.01, 0.03] | 0.007 | 0.02 [0.01, 0.04] | 0.001 | |

| CCI | − 0.07 [− 0.13, − 0.01] | 0.032 | − 0.05 [− 0.11, 0.02] | 0.147 |

Quality of life was assessed using the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL), with 19% of MQOL scores requiring imputed data for at most two (out of four) subscales if at least half but not all questions were answered

AKPS, Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index

When symptom burden was added to the fully adjusted model examining associations between participant characteristics and quality of life, the association between polypharmacy and quality of life weakened (adjusted beta − 0.03; p = 0.045). This association was significantly different from the association between polypharmacy and quality of life in the model without symptom burden (p = 0.008) (see Table 4). The test for an interaction between polypharmacy and symptom burden was not significant (p = 0.605).

Table 4.

Mediation analysis for the effect of symptom burden on the association between polypharmacy and quality of life

| Without covariates | With covariates* | |

|---|---|---|

| β [95% CI] (p value) (N = 239) | β [95% CI] (p value) (N = 238) | |

| Direct effect (c’)† | − .035 [− .071, 0.000] (0.051) | − .031 [− .064, 0.003] (0.071) |

| Indirect effect (ab)† | − .030 [− .052, − .008] (0.007) | − .028 [− .048, − .007] (0.008) |

| Total effect (c)† | − .065 [− .099, − .031] (< .001) | − .059 [− .094, − .023] (0.001) |

| Proportion of total effect mediated (ab/c) | 0.461 | 0.473 |

| Ratio of indirect to direct effect (ab/c’) | 0.855 | 0.897 |

| Ratio of total to direct effect (c/c’) | 1.855 | 1.897 |

Normal-based bootstrapped 95% CI and p value with –vce- option in Stata 15 (no. of bootstrap replications = 200)

*Covariates in the model are gender, age, primary DX, hospice, AKPS (Australia-Modified Karnofsky Performance Status), and CCI (Charlson Comorbidity Index)

†The direct effect (c’) is equal to the association between polypharmacy and quality of life when symptom burden is included in the model. The total effect (c) is equal to the association between polypharmacy and quality of life when symptom burden is not included in the model (c’ + ab). Without mediation, c should equal c’. Because there is mediation, c and c’ are different

DISCUSSION

In a cohort of adults with advanced, life-limiting illness, polypharmacy was associated with both higher symptom burden and lower quality of life. Furthermore, adjusting for symptom burden weakened the association between polypharmacy and quality of life, suggesting that worse quality of life associated with polypharmacy may be related to medication-associated symptoms.

A particularly concerning example of polypharmacy is the “prescribing cascade,” in which a medication-related side effect leads to the prescription of additional medications.26 For example, in one troubling case, a calcium channel blocker prescribed to an older woman for hypertension caused lower extremity edema. A diuretic prescribed to treat the lower extremity edema led to urinary incontinence. The anticholinergic prescribed to treat the urinary incontinence caused dry mouth, for which a salivary stimulant was prescribed. This patient eventually lost her balance and fell, leading to a prolonged hospital stay in which the “prescribing cascade” was identified and corrected.27 Misinterpreting medication-related adverse effects as new conditions can lead to unnecessary increases in both polypharmacy and symptom burden.

Efforts to alleviate the burden of polypharmacy and improve quality of life for patients with advanced, life-limiting illness will require clinician and patient education, accompanied by patient-centered decision-making. All clinicians caring for older and/or seriously ill patients should learn targeted approaches to deprescribing, and these approaches should be employed routinely.28 Evidence-based guidelines can help inform many deprescribing decisions.29, 30 Successful deprescribing also requires conversations with patients about the benefits and risks of medications. Patient preferences should help guide deprescribing decisions, particularly when the trade-off between risks and benefits is uncertain. Processes to support deprescribing across health systems must take into account perceived barriers and facilitators to minimizing potentially inappropriate medications.31, 32 Publicly available online resources offer useful deprescribing tools for patients and clinicians.33

This analysis builds on a growing body of research demonstrating associations between polypharmacy and poor quality of life. For example, in a cross-sectional study conducted among 634 functionally independent, community-dwelling older adults in Spain, polypharmacy defined as 3 or more drugs consumed daily was associated with poor health-related quality of life.5 In a separate Spanish study conducted among older adults who used 5 or more medications recruited from primary care practices, polypharmacy defined as using 10 or more medications was strongly associated with poorer health-related quality of life.6 Additional studies of polypharmacy and quality of life among older adults residing in nursing facilities have reported mixed results.34, 35 The present study adds to this work by demonstrating an association between polypharmacy and lower quality of life among adults with serious illness and a limited life expectancy (the median survival of this cohort was approximately 7 months)11 and suggests that worsening symptoms contribute to lower quality of life.

Significant medication burden placed on patients near the end of life warrants careful consideration.8 Medications used to treat serious illness and alleviate symptoms are often added to medications used for primary disease prevention or to control non-life-threatening conditions. Without careful attention to whether chronic medications remain necessary, polypharmacy among patients with limited life expectancies can easily become quite high.8 Even among actively dying patients, non-essential medications are often continued.36

In our study, patients with high polypharmacy had higher symptom burden than patients with lower polypharmacy, and these differences were clinically significant.19 The relationship between polypharmacy and symptom burden is likely bidirectional, as patients near the end of life also accumulate medications to treat symptoms. However, in a separate analysis of the types of medication used by this cohort, opioids were not among the most common medication classes prescribed, and only 4.1% of all medications prescribed were non-opioid analgesics.8 An alternative explanation for these findings is that patients with poorer quality of life are sicker and therefore need more medications. Our finding that adjusting for symptom burden weakens the relationship between polypharmacy and quality of life suggests that medication-related symptoms may be an important concern in this cohort, but conducting this analysis using cross-sectional data cannot confirm the direction of associations.

This study has several limitations. First, the cohort included patients with advanced, life-limiting illness who were willing to be enrolled in a randomized trial of the safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy. Not all patients with advanced illness would be willing to stop a statin medication, and associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life may differ in other seriously ill populations. Second, cross-sectional data did not allow us to explore the impact of polypharmacy on symptom burden or quality of life over time. Furthermore, this analysis did not allow us to determine causality, which would require a randomized trial. Third, the data available for this analysis did not include medication type or the proportion of medications taken regularly versus as needed. We were therefore unable to explore whether certain medication classes were most strongly associated with patient-reported outcomes. Finally, imputed data for total symptom burden and quality of life scores was required for a minority of participants.

In conclusion, we found that polypharmacy was associated with higher symptom burden and worse quality of life in adults with life-limiting illness. Areas for future research include developing deprescribing strategies to reduce the use of inappropriate medications in patients with limited life expectancies. Implementing and prospectively evaluating such strategies may help to determine the direction of associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life and improve patient-centered outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Funding Information

This project is supported by the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research U24NR014637, by UC4NR12584, and by 5KL2TR1856.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

Author Amy Abernethy, MD, is an employee of Roche Group/Flatiron Health, has received honoraria from Roche/Genentech in the last 3 years, has stock ownership/options with Athena Health, has a current patent pending for a technology that facilitates the extraction of unstructured information from medical records, and is the owner of Orange Leaf Associates and a senior advisor to Highlander Partners (http://highlander-partners.com/). There are no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

This work was presented as an oral presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine annual meeting on April 12, 2018.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Centre for Health Development. A Glossary of Terms for Community Health Care and Services for Older Persons; 2004.

- 2.Cooper JA, Cadogan CA, Patterson SM, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy in older people: a Cochrane systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009235. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Dreischulte T. The rising tide of polypharmacy and durg-drug interactions: population database analysis 1995-2010. BMC Med. 2015;13:74. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0322-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the United States From 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1818–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machon M, Larranaga I, Dorronsoro M, Vrotsou K, Vergara I. Health-related quality of life and associated factors in functionally independent older people. BMC Geriatrics. 2017;17:19. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0410-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montiel-Luque A, Nunez-Montenegro AJ, Martin-Aurioles E, Canca-Sanchez JC, Toro-Toro MC, Gonzalez-Correa JA. Medication-related factors associated with health-related quality of life in patients older than 65 years with polypharmacy. PloS One. 2017;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.McLean S, Sheehy-Skeffington B, O’Leary N, O’Gorman A. Pharmacological management of co-morbid conditions at the end of life: is less more? Irish Journal of Medical Science. 2013;182:107–12. doi: 10.1007/s11845-012-0841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeil MJ, Kamal AH, Kutner JS, Ritchie CS, Abernethy AP. The Burden of Polypharmacy in Patients Near the End of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2016;51:178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weir MR, Fink JC. Safety of medical therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Nephor Hypertens. 2014;23(3):306–13. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000444912.40418.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potosek J, Curry M, Buss M, Chittenden E. Integration of palliative care in end-stage liver disease and liver transplantation. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1271–1277. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH, Jr., et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175:691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Marcum ZA, Gellad WF. Medication adherence to multidrug regimens. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2012;28:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moroni M, Zocchi D, Bolognesi D, et al. The ‘surprise’ question in advanced cancer patients: A prospective study among general practitioners. Palliative Medicine. 2014;28:959–64. doi: 10.1177/0269216314526273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray S, Boyd K. Using the ‘surprise question’ can identify people with advanced heart failure and COPD who would benefit from a palliative care approach. Palliative Medicine. 2011;25:382. doi: 10.1177/0269216311401949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abernethy AP, Shelby-James T, Fazekas BS, Woods D, Currow DC. The Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice. BMC Palliative Care. 2005;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PCRC Data Available for Secondary Analyses. Statin Discontinuation. Available at http://palliativecareresearch.org/corescenters. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 17.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. Journal of Palliative Care. 1991;7:6–9. doi: 10.1177/082585979100700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, Do R, et al. A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, Khamash O, et al. Minimal clinically Important difference in the physical, emotional and total symptom distress scores of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(2):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, Provost M, Rowe J, Tong K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliative Medicine. 1997;11:3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods of Information in Medicine. 1993;32:382–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1634956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatrics. 2017;17:230. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological Methods. 2013;18:137–50. doi: 10.1037/a0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor ABMD, Tein JY. Tests of the Three-Path Mediated Effect. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:241–69. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fritz MS, Taylor AB, Mackinnon DP. Explanation of Two Anomalous Results in Statistical Mediation Analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2012;47:61–87. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2012.640596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. The prescribing cascade revisited. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389:1778–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen PV, Spinelli C. Prescribing cascade in an elderly woman. Canadian Pharmacists Journal : CPJ = Revue des pharmaciens du Canada : RPC. 2016;149:122–4. doi: 10.1177/1715163516640811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bain KT, Holmes HM, Beers MH, Maio V, Handler SM, Pauker SG. Discontinuing Medications: A Novel Approach for Revising the Prescribing Stage of the Medication-Use Process. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1946–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Canadian Family Physician. 2017;63:354–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrell B, Black C, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing antihyperglycemic agents in older persons: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Canadian Family Physician. 2017;63:832–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006544. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs & Aging. 2013;30:793–807. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deprescribing.org. Available at: https://deprescribing.org/about/. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 34.Lalic S, Jamsen KM, Wimmer BC, et al. Polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity as factors associated with staff informant rated quality of life in residents of aged care facilities: a cross-sectional study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2016;72:1117–24. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosboom PR, Alfonso H, Almeida OP, Beer C. Use of Potentially Harmful Medications and Health-Related Quality of Life among People with Dementia Living in Residential Aged Care Facilities. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra. 2012;2:361–71. doi: 10.1159/000342172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams BR, Amos Bailey F, Kvale E, et al. Continuation of non-essential medications in actively dying hospitalised patients. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2017;7:450–457. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]