Abstract

Background

Different conceptual frameworks guide how an organization can change its policies and practices to make care and outcomes more equitable for patients, and how the organization itself can become more equitable. Nonetheless, healthcare organizations often struggle with implementing these frameworks.

Objective

To assess what guidance frameworks for health equity provide for organizations implementing interventions to make care and outcomes more equitable.

Study Design

Fourteen inequity frameworks from scoping literature review 2000–2017 that provided models for improving disparities in quality of care or outcomes were assessed. We analyzed how frameworks addressed key implementation factors: (1) outer and inner organizational contexts; (2) process of translating and implementing equity interventions throughout organizations; (3) organizational and patient outcomes; and (4) sustainability of change over time.

Participants

We conducted member check interviews with framework authors to verify our assessments.

Key Results

Frameworks stressed assessing the organization’s outer context, such as population served, for tailoring change strategies. Inner context, such as existing organizational culture or readiness for change, was often not addressed. Most frameworks did not provide guidance on translation of equity across multiple organizational departments and levels. Recommended evaluation metrics focused mainly on patient outcomes, leaving organizational measures unassessed. Sustainability was not addressed by most frameworks.

Conclusions

Existing equity intervention frameworks often lack specific guidance for implementing organizational change. Future frameworks should assess inner organizational context to guide translation of programs across different organizational departments and levels and provide specific guidelines on institutionalization and sustainability of interventions.

KEY WORDS: inequities, disparities, organizational change, frameworks, implementation

BACKGROUND

Healthcare organizations have aimed to reduce inequities in access and quality of care for over 30 years.1 While some efforts have shown success in minimizing disparities,2, 3 others have documented stagnation or even exacerbation.4, 5 Analogous to the Waze driving navigation software, different conceptual frameworks guide how an organization can change its policies and practices to make care and outcomes more equitable for patients, and how the organization itself can become more equitable. Nonetheless, healthcare organizations often struggle with implementing these frameworks.6–9

Change is complex due to the multifaceted nature of healthcare organizations, and because equity-focused frameworks call on healthcare organizations to simultaneously address the needs of both patients and employees. Comprehensive equity efforts require healthcare providers to tailor access and processes of care to different population groups, while also changing internal processes to promote diversity and inclusion within the organization, such as through employee hiring and retention. Interventions require changing policies, processes, and practices throughout multiple levels of the organization.10, 11 Few healthcare organizations engage in comprehensive, multifaceted efforts to improve equity.12

Organizational change in general is difficult;13, 14 literature indicates that over 70% of organizations do not achieve their aspired change goals.15 Major obstacles include the difficulty of changing the organizational culture and environment, carving out a new course when the organization seems to be functioning well, and planning and executing implementation.16 Barriers arise from institutionalization, in which the existing cognitive activities and regulative elements in the organization and its environment are resilient.10 People’s intentions, actions, and rationality are conditioned by the institution they wish to change.17 Incorporating change within healthcare organizations is especially difficult because of the highly professionalized setting and embedded policy legacies, constituencies, and structured processes.16, 18 Implementing equity frameworks requires transformational change. All organizational levels and professional backgrounds, such as administrative and clinical staff as well as patients, must participate to adapt to the shifting environment.19, 20

This paper reviews and assesses what guidance frameworks for health equity provide for organizations implementing interventions to make care and outcomes more equitable. The objectives are twofold: (a) Identify existing frameworks that aim to assist organizations in reducing inequities in patient care and outcomes, and (b) assess to what extent the frameworks address key organizational change elements.21, 22

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review of the literature. Scoping reviews map key concepts, evidence, and gaps in research by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge.23, 24 This method can address broader and more heterogeneous questions than systematic reviews. Scoping reviews can include studies of many different methodological designs, not necessarily assessing their quality.25–27

Search Strategy

We searched the following health and social science databases for the years 2000–2017: Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Sociological Abstracts, and Cochrane. We also manually searched relevant websites. References from relevant articles were scanned to identify other sources Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| A. Electronic Databases –databases were searched using the following search terms and search string: | |

| 1. framework OR roadmap OR model OR “action model” [title, abstract and keywords] | |

| 2. disparities* OR *equity [title, abstract and keywords] | |

| 3. “healthcare organizations” OR “healthcare services” OR “healthcare provider” [title, abstract and keywords] | |

| 4. 1 AND 2 AND 3 | |

| B. Websites manually searched: | |

| American Hospital Association, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Joint Commission, National Quality Forum, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); International Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH) Network, VicHealth – Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Close the Gap – Department of Health Australia, NHS Equality and Health Inequalities Hub |

Analysis

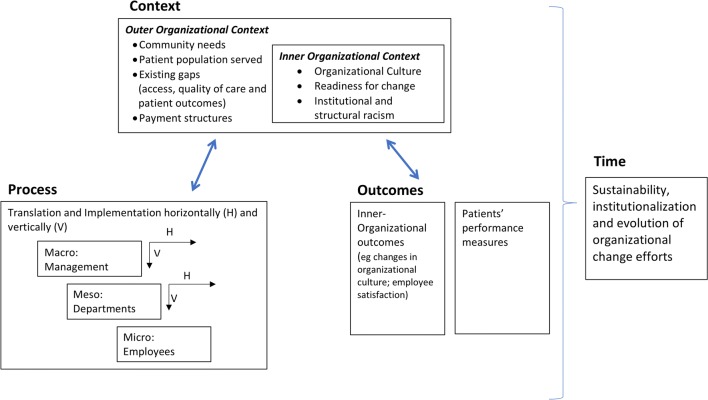

We assessed the frameworks utilizing Armenakis and Bedeian (1999) and Pettigrew and colleagues’ (2001) analytical underpinnings for reviewing organizational change literature (Fig. 1).21, 28 Our conceptual model addresses the four major multilevel and multifaceted constructs of organizational change processual analysis: context, process, outcomes, and time (Fig. 1).29

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Context

Collective and individual agency drive change processes, yet these actions cannot be understood without understanding the pre-existing outer and inner organizational contexts that affect information, insight, and influence. Outer organizational context includes the economic, social, political, competitive, and sectoral environments in which the organization is located. It includes, for example, the economic status of surrounding neighborhoods, the demographics of the patient population, and place of residence. Additionally, the outer context also reflects powerful national policies and payment structures, such as fee for service reimbursement, value-based payment, and national health insurance coverage.30

Inner organizational context relates to the interplay between the organizational structure and culture, including employees’ readiness for change, differential needs and structures of organizational department or units, and existing knowledge and skills of employees. Organizational culture impacts employees’ perceptions of the need for organizational change, innovation, diversity and equity, and their ability to carry out change. For example, a hierarchical organization culture will require top–down change directed by executive leadership, making it difficult for bottom–up change efforts by frontline employees to succeed.

The interaction between outer and inner contexts shapes the implementation process, enabling or constraining change.21

Process

Organizational change processes, conceived and initiated at the macro top management organizational level, are implemented in and across local units.31 Process analysis attempts to understand how the initiative is translated and diffused across multiple departments as well as throughout the different levels from management to frontline staff. Levels of process analysis include the organization (macro), the department or unit (meso), and individual (micro) levels.28 This analysis focuses on the way in which people understand, modify, add, or deflect organizational change throughout its diffusion across and within units of the organization, assessing the relationship between what exists and what is created.32 An example of such a translation process is organizational “sensemaking,” a process of social construction in which individuals attempt to interpret and explain a set of cues, such as change initiatives, to create a plan of action for dealing with uncertainty or ambiguity.33, 34

Outcomes and Time

Ultimately, organizational change is assessed through outcome performance measures. Continuous monitoring of outcomes enables understanding change not as a snapshot process, but rather as a continuous cycle over time.21

We assessed inequity reduction frameworks for their consideration of context, process, outcomes, and time. Specifically, we examined and rated on a three-point scale (do not address, partially address, and address), the extent that these frameworks considered the following: (1) Embeddedness of change in multiple contexts, focusing on the outer organizational context of the surrounding environment, and the inner organizational context of structure and culture;12, 35 (2) process of implementing change across multiple organizational settings, and guidance on translation and organizational “sense making” of the equity intervention;36 (3) impact of change processes on performance measures, including clinical and organizational outcomes, such as change in organizational culture and hiring practices; (4) sustainability of change over time.37 Authors rated the different frameworks according to the assessment criteria and discussed differences in ranking to reach consensus.

Member Check with Authors of Frameworks/Models

After we identified and assessed the inequity reduction frameworks, we emailed and/or telephoned the authors and/or organizations who created them, requesting a short phone interview to conduct a member check of the findings to improve the accuracy and validity of our review.38 Prior to interview, authors were sent a draft of the manuscript and assessment table. During the interview, authors were asked to explain their framework. The assessment table was then reviewed together so that authors may have the opportunity to express their agreement or disagreement with our assessment as well as add additional insight. The study was exempt from institutional review board at both Bar-Ilan University and the University of Chicago.

RESULTS

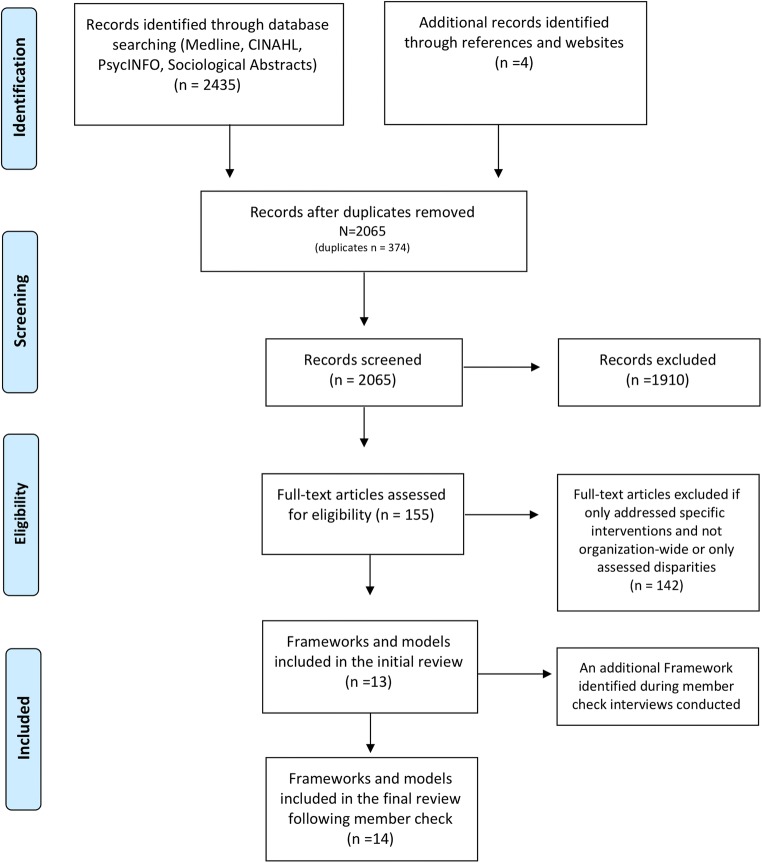

As shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) diagram in Figure 2, a total of 2439 records were identified. Duplicate records were removed. The remaining 2065 records were screened by one of the authors (SS) for inclusion including focus on disparities or inequities and provision of a practical model, roadmap, or framework for improving access and/or quality of care. Records were excluded if the study documented or evaluated only a specific intervention and not an organization-wide initiative, or only the state of disparities. Of the records screened, 155 full texts were retrieved and assessed for eligibility.

Figure 2.

Conceptual organizational change model guiding assessment of reviewed frameworks addressing equity.21, 28

We initially found 13 different models and frameworks addressing inequity reduction. We conducted 9 interviews verifying with authors our understanding of their frameworks according to the organizational change constructs.20, 39–47 Four authors/organizations did not reply. During the member check process, one author noted an updated model that we included in this review, leading to a final set of 14 models to analyze.

Ten of the 14 models were from the United States (US). Additional frameworks were from the European Union (EU) (1), United Kingdom (UK) (1), and Australia (2). Models were developed by government (United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Health Service (NHS), Department of Health Victoria, Australia),39, 48–50 healthcare associations (Health Promoting Hospitals Network, American Hospital Association),43, 47 not-for-profit organizations (National Quality Forum, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Kaiela Institute),42, 46, 51, 52 and academia.20, 40, 41, 44 Most frameworks addressed equity efforts through a strategy focused mainly on implementation and improvement of organizational cultural competence.

Tables 2 depicts our evaluation of frameworks according to organizational change constructs, assessing how they relate to context, process, outcomes, and time.

Table 2.

The Evaluation of Equity Frameworks According to the Analytical Underpinnings of Organizational Change

| Framework: short description* | Context: Pre-existing organizational conditions | Process: Translation and implementation | Outcomes | Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer context | Inner context | Organization level | Department level | Individual level | Organizational performance measures | Patient performance measures | Sustainability and evolution over time | |

|

CLAS Standards (US): (Office of Minority Health, US Department of Health and Human Services) The National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care are 15 standards that can be grouped into three main themes: governance, leadership and workforce; communication and language assistance; and engagement, continuous improvement and accountability.48 |

+ | +/− | + | − | +/− | − | +/− | +/− |

| Organizations should perform an assessment of community assets and needs to design and inform service delivery | Organizations should conduct an audit assessing the cultural competence of employees | The standards focus largely on macro-organizational level and relate to policy, leadership, recruitment of diverse staff, training, and assessment of the entire organization | No relation to individual-level actions and needed competencies, aside from assuring competencies of translators | There are no specific clinical outcome measures attributed to the Standards. Organizations need to stratify quality metrics data by social risk factors and collect and evaluate CLAS-related measures | Sustainability should be communicated to all stakeholders. No guidelines on how to achieve | |||

|

Finding Answers: Roadmap to Reduce Disparities* (US): A six-step model guiding organizations on disparity reduction that includes identification of disparities and commitment to reduce, implementation of quality improvement structure that includes equity, designing, and implementing interventions and sustaining them over time.20 |

+ | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Assessment of patient needs and existing disparities | The roadmap calls for assessment of organizational capacity to understand how available resources match or mismatch the impending change | Design intervention/s considering six levels of influence such as patient and provider, as well as multiple organizational levels ranging from the macro such as changing the organizational culture, to the department meso level when considering restructuring care teams, or the micro level through targeting individual staff behavior and training | Financial impact on the organization as well as fostering a culture of equity | According to predetermined quality improvement measures | Create a proactive plan for sustainability through institutionalization and proper financial models | |||

|

A Practical Framework of Cultural Competence to Reduce Disparities* (US): The framework addresses three areas for action: organizational, structural, and clinical cultural competency. Different from other frameworks, this model proposes three areas for interventions rather than looking at the overall organizational process.40 |

− | − | + | − | +/− | − | − | − |

| Increase leadership and workforce diversity, translation services, and culturally adapted materials | Training of staff to better manage the clinical encounter | |||||||

|

Disparities Leadership Program* (US): The model is built on the 8-step Kotter model for change management that includes identification of gaps, securing leadership buy-in, tailoring and implementing a project focused on inequities.41 |

− | −/+ | + | − | −/+ | − | + | − |

| As the program is focused on change management, it does not explicitly address community needs | Assess current status through stratified data. Acknowledges importance of organizational culture but no pre-assessment | Secure leadership buy-in and create a sense of urgency for implementing equity | Acknowledges the need to involve and engage people from mid-management and frontline staff and create awareness | According to predetermined quality improvement measures | ||||

|

A Roadmap for Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Development: The Four I’s for Health Equity* (US): (National Quality Forum) The roadmap focuses on disparity reduction through measurement, centering on identification of gaps through agreed-upon performance measures, and employing quality improvement interventions for achieving reduction.43 |

+ | −/+ | + | − | − | + | + | − |

|

Recognize needs of the community through gaps identified in outcome-driven performance measures Identify other agencies that influence individuals’ care for future partnerships |

There is no direct assessment of intra-organizational needs, but uses agreed-upon measures to assess organizational baseline performance | Focus on creating a culture of equity and institutionalizing organizational structures that support equity through training, workforce diversity | The framework is measurement driven and therefore focuses both on organizational (such as cultural competence for assessment of organizational culture) as well as clinical performance measures | |||||

|

Achieving Health Equity* (US): (Institute for Healthcare Improvement): A set of five elements outlining healthcare organization’s focus area for achieving disparity reduction. The five domains include: equity as a strategic priority, establishment of a governance structure, deploying different strategies to address Social Determinants of Health (SDH), decrease institutional racism, and development of community partnerships.51 (IHI White paper) |

+ | − | + | − | +/− | − | + | − |

| Understanding not only the health needs but also the wider impact of SDH on surrounding communities | Focusing on securing commitment of leadership as well as establishing a steering committee to forward health equity work; staff training at all levels on equity; addressing structural biases in physical space, insurance plans, and provider–patient relationships | Provision of better economic opportunities through increased wages of support staff | There is no relation to possible organizational measures | The framework suggests different measurement approaches including stratification and bottom–up approach aggregating different patient attributes such as race, gender, and socio-economic status. | ||||

|

Equity Delivery System (UK): (National Health Services) A system to assist organizations to improve the services they provide their local communities as well as provide better working environments, free of discrimination, for NHS employees, while meeting the requirements of the Equality Act 2010 addressing disadvantaged groups. (NHS –EDS2)53 |

+ | − | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| Identify local interests with assistance from local stakeholders | Increasing staff diversity, maintaining health of the workforce, training staff | Relates to the role of middle and line managers to support and motivate staff | Staff diversity, training, and support as well as leadership’s action to support equity, not only that of senior leadership but also of middle and frontline staff managers as well | Health outcomes as well as patients’ access and experience | ||||

|

Cultural Responsiveness Framework (AU): (the Department of Health and Human Services Victoria) The framework articulates six broad standards and key measures to improve healthcare organizations’ performance in issues of quality and safety. The standards aim to guide and support organizations through a strategic coordination and planning process. (Health.Vic)53 |

− | +/− | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| While not addressed directly in the standards, the Department of Health does call for a planning with representation of all relevant stakeholders, examining organizational supports and resources required for development | The framework focuses on organization-wide implementation addressing macro-level strategies such as training workforce and language provision services | Specific measures include number of staff trained and staff employed | Patient satisfaction is addressed but no clinical outcome metrics | |||||

|

Aboriginal Cultural Competence Framework (AU): (Kaiela Institute) Part of the “Close the Gap” government initiative, the framework has five focus areas: organizational effectiveness, engagement and partnerships, cultural competence services, workforce development, and public image and communications. They implemented through a set of 8 standards and 21 indicators.52 (Kaiela Institute) |

+ | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Assessment of the fit of provided services to Aboriginal consumers through self-assessment and community partnerships | Developing an Aboriginal cultural competence plan that includes designating and training leadership, hiring of Aboriginal staff, and cultural competence training for all employees | No specific outcome measures are given, but do relate in general to the goal of the “Close the Gap” initiative in improving life expectancy | ||||||

|

Equity Standards* (EU): (Health Promoting Hospitals) Developed and implemented in the Health Promoting Hospital Network, consists of 5 broad standards focusing on Policy, Access, Quality of Care, Participation, and Promotion.43 (Health Promoting Hospitals) |

+ | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| The Standards address outer organizational context, focusing on patients’ lifeworlds looking at the individual patient rather than making general assumptions through community representatives | The focus is on the macro organizational level addressing policy such as employment of diverse staff, the role of leadership, and participation in larger societal initiatives | The model states that there should be no general training but rather that staff learn through individual patient encounters | No clear reference to clinical outcome measures. | |||||

|

Conceptual Framework for the Provision of Culturally Competent Services in Public Health Setting* (US): The framework addresses the major entities that have roles and impact provision of service: the client system, the provider system which includes the organization, service, and individual provider sub-system, and the context system which refers to the outer environment impacting services.45 |

− | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| No prior assessment of public health needs | Availability of resources for provision of services | The framework does not describe how or what actions are needed, but rather what are the characteristics of an organizationally competent entity. These include retention of diverse staff, as well as knowledge, awareness, and skills such as the understanding of the culture of clients versus the culture of the organization, flexibility in provision of services and advocacy for appropriate services | No explicit measures are given. Yet there is reference in the framework to assessment using the cultural competence gauge based on the level of activity in a system | |||||

|

A Framework for Cultural Competence in Healthcare Organizations* (US): Provides a framework to guide organizations on integration of cultural competence into all organizational tiers through the creation of governance, vision and mission, a strategic plan and evaluation.44 |

+ | +/− | + | +/− | + | − | + | + |

| Assessment of patients’ needs | Organizational self -assessment of cultural competence | Creation of mission and policy; appointing a steering committee for planning, implementation, and assessment including appointment of CEO, staff retention, and training | The framework does call for programs to identify the roles and responsibilities of department managers | Awareness to differential levels of involvement and communication of the organization to the individual employee | Evaluating staff’s cultural competence level | Clinical outcomes according to predefined measures | Continuous monitoring and evaluation over time are essential, and should be complemented by continued education and training for providing culturally competent care | |

|

Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model* (US): (Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services) The model addresses 9 different cultural competency techniques such as interpreter service, staff recruitment retention and training, coordination with traditional leaders, etc., and their effect on changing clinical and patient behavior and the association with good health outcomes.39 |

+/− | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| Identifying traditional healers | Increasing staff diversity to improve staff–patient concordance, cultural competency training and implementation of practices such as culturally competent health promotion | General measures such as increased functioning | ||||||

|

Equity of Care* (US): (American Hospital Association) A three-step framework designed as a practical tool for hospitals to implement disparity reduction initiative. The three phases include collection of Racial, Ethnic and Language preference (REAL) data, cultural competence training, and increasing diversity in leadership and governance.47 (www.equityofcare.org) |

+ | − | + | − | + | +/− | + | − |

| Assessment of patient needs according to REAL data as well as patients’ satisfaction | Large macro change processes according to the three focus areas | No explicit detail on departmental adaptation | Address in specificity the role of Chief Diversity Officer including needed knowledge and skills such as change management and innovation | Assessment of workforce diversity | Quality metrics including patient satisfaction | |||

*Frameworks reviewed with authors; ranking: −, no action point; +/−, partial address; +, addresses the issue

Context

Most frameworks primarily focused on the organization’s outer context, stressing the importance of conducting a needs assessment for tailoring strategies for change. The main strategy for identifying existing disparities and population needs is analyzing demographic and performance data across patients’ race and ethnicity (e.g., whether patients are predominantly African-American or Latina, what is the percentage of non-English speakers who may require language assistance, clinical performance data stratified by patients’ race and ethnicity). Additional strategies include discussions with local community representatives about their perspectives and needs, assessment of service gaps and wider social determinants of health, and appraisal of existing community resources and agencies providing care. The Equity Standards framework presents a unique approach, as it focuses not on the population but on the individual patient through the “lifeworld” approach. This framework stresses that care needs should not be assessed generally through standardized quality improvement indicators, but rather through a person-centered approach understanding individual patients’ needs.43 Most frameworks do not address the effect of payment structures on healthcare organizations’ outer context, how payment may affect equity, and the extent to which payment reform may be needed. The Achieving Health Equity framework encourages organizations to review payment models and suggests that a bundled payment model would account for the healthcare needs of marginalized populations.46

The inner organizational context of structure and culture was often not addressed. A few models suggested broadly that organizations assess existing resources to understand advantages and limitations, or create baseline measures of organizational performance 20, 42, 50. The National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services Standards (CLAS) Standards framework and the Disparities Leadership Program recognize the importance of existing culture.41, 48 In addition, CLAS suggests conducting an audit to assess the degree of cultural competence of employees prior to implementation.48 Few frameworks explicitly assess and discuss structural and institutional racism as part of implementation.46

Process

Most of the frameworks address the implementation process at the macro level of the whole organization. Common strategies included organization-wide training on cultural competence, leadership buy-in, and increasing workforce diversity. However, these guidelines do not specifically guide the tasks and skills required for successfully implementing the initiative throughout the differential intra-organizational departments. For example, the CLAS standard 9 states that an organization needs to: “Establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies and management accountability, and infuse them throughout the organization’s planning and operations.” However, it is not clear what are the specific processes and skills required for “infusing” equity, leaving the healthcare organization to interpret and devise the strategy on its own.

The Roadmap to Reduce Disparities model differs in its approach by creating a menu of intervention options based on analysis of six levels of influence, including provider, microsystem, and organization. This model offers change directives, not only on the macro but also on the meso and micro levels through initiatives such as team restructuring or tailored individual training. The menu of possibilities, rather than necessarily a whole-system approach, allows organizations to choose the extent of change they would like to implement, i.e., whether it be in a specific area of care or the organization at large. However, the translation process for implementing equity throughout the organization both across and within different departments is not addressed in detail.

Some reviewed models address the implementation process within specific micro-level employee groups. For example, the CLAS Standards refer specifically to the training of translators, the Equity Standards call for tailored clinical staff training around patient encounters, and the Achieving Health Equity framework calls for increased wages of support staff residing in surrounding disadvantaged communities. None of the frameworks or models address implementation at the meso department level. However, the Equality Delivery System model of the UK National Health Service, as well as the Disparities Leadership Program in the US, address the role of middle managers in supporting and motivating staff who are implementing equity-focused efforts.

Outcomes

Frameworks addressed clinical and patient experience performance measures but not measures of organizational culture or structure. Most models reference quality improvement equity-focused score cards, letting the organization decide which quality measures to evaluate. The Achieving Health Equity framework suggests measuring performance for individual sociodemographic attributes (e.g., black, female, low-income), combining the individual measurements into a summary index, and then comparing the index to the best health level among all groups as the reference.46

Time

Only three of the models address sustainability. The CLAS standards iterate the importance of continuously communicating achievements to relevant stakeholders as a broad and general guideline on sustainability. The Roadmap to Reduce Disparities calls for a proactive plan to ensure sustainability. The Framework for Cultural Competence in Health Care Organizations states the importance of continued monitoring, evaluation, and training of staff.

DISCUSSION

Overall, we found that current equity intervention frameworks do not fully address key issues relevant to successful implementation of organizational change. Existing models focus on assessing the outer organizational context mainly through analyzing racial and ethnic data and interacting with community representatives, implementing macro-level change processes such as cultural competence training of staff and increasing workforce diversity, and assessing patient outcomes.

Organizational theories stress the need for elasticity in the shape and pace of change.54 Assessment of the inner organizational context is needed to recognize possible barriers for implementation. Evaluation needs to include readiness for change of the organization, work group, and individuals,12, 35 as resistance of employees can be a critical driver of failure.55 In their systematic review of cultural competence and improved patient outcomes, Truong and colleagues (2014) noted not only the sparse success of isolated cultural competence–based initiatives in impacting patient outcomes, but also the effect of organizational inner context on hindering implementation of these programs.56 Cultural competency training generally needs to be integrated with structural organizational change interventions to improve clinical performance measures. Additionally, to be most effective, organizations should engage in difficult discussions about how structural and institutional racism impacts their daily processes.57 Structural racism, such as residential segregation or care systems designed to preferentially attract affluent patients, systematically shapes healthcare access, utilization, and quality for racial and ethnic minority patients.58

The focus of existing frameworks on macro-level organizational implementation processes poses another challenge and area for improvement. Current guidelines are general and overarching, leaving the process of intra-organizational translation, adaptation, and implementation across different department and staff levels a black box for organizations to decipher. Middle managers entrusted with driving change and implementation often lack the knowledge and skills to effectively translate change processes.36, 59 Parand and colleagues (2010) compared the perceptions of frontline and managerial staff on the factors important for successful implementation of a quality improvement initiative focused on quality and safety. They found that managers viewed learning sessions and training events to be the most important factors of the program, while frontline staff considered clinical and administrative systems and management support to be central to success.60 These findings highlight the complementary needs of managers and frontline staff. Managers seek training that would expand their knowledge and equip them with tangible skills for translating equity-focused organizational change to everyday work processes. Staff require a clear understanding of tasks required and organizational support systems to implement the initiative.

Studies detailing the implementation and evaluation of the CLAS framework, for example, have noted that most organizations implement the Standards partially.8, 61, 62 Weech-Maldonado and colleagues (2012) found that hospitals that adopted the CLAS Standards focused mainly on retaining translators and adapting culturally and language-appropriate materials.63 The standards pertaining to communication and language assistance are clear with specific change tasks, while other CLAS Standards are ambiguous. Ogbolu and Fitzpatrick (2015) argue that the sluggish adoption of the Standards stems from the difficulties of translating the Standards into policies and clinical practice across different healthcare settings.7

Finally, most existing equity frameworks do not adequately address sustainability and institutionalization of equity-focused change efforts. Sustainability will not occur without a conscious effort, addressing factors such as what values the organization truly prioritizes and how to create the business case for equity.30, 64 Intervention practices and procedures are frequently abandoned due to “initiative decay” as organizational resources are diverted to other areas.37 Guidelines on institutionalization of equity-focused change initiatives need to include specific strategies for rollout, diffusion, and sustainability.65

LIMITATIONS

Our review did not include every patient term for social risk (e.g., migrant, refugee, and underserved) to the search filter for systematic reviews, and thus some equity frameworks may have been excluded. However, it is unlikely that the overall findings would be significantly different as this paper reviews models from multiple healthcare systems, countries, and contexts. Additionally, we may have misinterpreted or misclassified the frameworks and models. However, we were able to confirm the interpretations with authors of most of the models.

CONCLUSIONS

Existing inequity reduction frameworks and models lack important guidance to organizations for the practical implementation of change efforts, tending to focus on broad 30,000-foot statements. Several clear recommendations for improving future frameworks can be posited. First, frameworks should include guidelines on assessment of inner organizational context parameters, such as readiness for change and institutional racism, prior to implementation of change initiatives. Second, organizations require specific guidance on how to implement equity within and across all organizational levels. To effectively crack the black box of implementation, the trickle-down and translation of macro-level policies into the day-to-day action of frontline staff must be clear. Management personnel should receive training in “Translational Management,” where they learn how to contextualize and implement equity in their specific departments. Finally, guidelines and strategies focusing on institutionalization and sustainability are crucial, considering competing organizational interests and changing environments. Providing organizations clear, effective, and concrete guidance on how to implement equity interventions has great potential for improving health equity.

Funding Information

Dr. Spitzer-Shohat was supported by a Rivo-Essrig Fellowship from the Department of Population Health, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar-Ilan University. Dr. Chin was partially supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (grant number NIDDK P30 DK092949), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Solving Disparities Through Payment and Delivery System Reform Program Office, and the Merck Foundation Bridging the Gap: Reducing Disparities in Diabetes Care National Program Office.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clarke AR, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, et al. Thirty years of disparities intervention research: what are we doing to close racial and ethnic gaps in health care? Med Care. 2013;51(11):1020-1026. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a97ba3 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Chin MH. Quality improvement implementation and disparities: the case of the health disparities collaboratives. Med Care. 2010;48(8):668-675. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e3585c [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Balicer RD, Hoshen M, Cohen-Stavi C, et al. Sustained Reduction in Health Disparities Achieved through Targeted Quality Improvement: One-Year Follow-up on a Three-Year Intervention. Health Serv Res. 2015. 10.1111/1475-6773.12300 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Jha AK, Zaslavsky AM. Quality reporting that addresses disparities in health care. JAMA. 2014;312(3):225–226. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt B, Whitman S. Black:White Health Disparities in the United States and Chicago: 1990-2010. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2015;2(1):93–100. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald KM, Schultz EM, Chang C. Evaluating the state of quality-improvement science through evidence synthesis: insights from the closing the quality gap series. Perm J. 2013;17(4):52–61. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogbolu Y, Fitzpatrick GA. Advancing Organizational Cultural Competency With Dissemination and Implementation Frameworks: Towards Translating Standards into Clinical Practice. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(3):203–214. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barksdale CL, Rodick Iii WH, Hopson R, Kenyon J, Green K, Jacobs CG. Literature Review of the National CLAS Standards: Policy and Practical Implications in Reducing Health Disparities. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2016. 10.1007/s40615-016-0267-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Chin MH, Goldmann D. Meaningful Disparities Reduction Through Research and Translation Programs. JAMA. 2011;305(4):404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott RW. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities. 4th edn. SAGE Publications; 2013.

- 11.McNulty T, Ferlie E. Reengineering Health Care : The Complexities of Organizational Transformation. Oxford University Press; 2004.

- 12.Rafferty AE, Jimmieson NL, Armenakis AA. Change Readiness: A Multilevel Review. J Manage. 2013;39(1):110–135. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs G, Van Witteloostuijn A, Christe-Zeyse J. A theoretical framework of organizational change. J Organ Chang Manag. 2013;26(5):772–792. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-09-2012-0137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnes B. Introduction: Why Does Change Fail, and What Can We Do About It? J Chang Manag. 2011;11(4):445–450. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2011.630507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnes B, Jackson P. Success and Failure In Organizational Change: An Exploration of the Role of Values. J Chang Manag. 2011;11(2):133–162. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2010.524655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner Burke W. Organization change: theory and practice, 5th edn. Sage Publications; 2017.

- 17.Battilana J, Leca B, Boxenbaum E. How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship. Acad Manag Ann. 2009;3(1).

- 18.Ferlie E. Analysing health care organizations: a personal anthology. Routledge; 2016.

- 19.Benzer JK, Charns MP, Hamdan S, Afable M. The role of organizational structure in readiness for change: A conceptual integration. Heal Serv Manag Res. 2017;30(1):34–46. doi: 10.1177/0951484816682396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992-1000. 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Pettigrew AM, Woodman RW, Cameron KIMS. Studying Organizational Change and Development: for Future Research. 2001;44(4):697–713.

- 22.Poole MS, Van de Ven AH. Handbook of Organizational Change and Innovation. Oxford University Press; 2004.

- 23.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heather LC, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Andrea CT, Perrier L, Kastner M, Moher D. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2008;6(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brien SE, Lorenzetti DL, Lewis S, Kennedy J, Ghali WA. Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armenakis AA, Bedeian AG. Organizational Change: A Review of Theory and Research in the 1990s. J Manage. 1999;25(3):293–315. doi: 10.1177/014920639902500303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettigrew AM. What is a processual analysis? Scand J Manag. 1997;13(4):337–348. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00020-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeMeester RH, Xu LJ, Nocon RS, Cook SC, Ducas AM, Chin MH. Solving Disparities Through Payment And Delivery System Reform: A Program To Achieve Health Equity. Health Aff. 2017;36(6):1133–1139. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albers Mohrman S, Tenkasi RV, Mohrman AM. The Role of Networks in Fundamental Organizational Change A Grounded Analysis. Role Netw J Appl Behav Sci. 2003;39(3):301–323. doi: 10.1177/0021886303258072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czarniwska B, Joerges B. Travels of Ideas. In: Czarniawska B, Sevon G, editors. Translating Organizational Change. New York: Walter de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maitlis S. The Social Processes of Organizational Sensemaking. Acad Manag J. 2005;48(1):21–49. doi: 10.5465/amj.2005.15993111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weick KE. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maitlis S, Christianson M. Sensemaking in Organizations: Taking Stock and Moving Forward. Acad Manag Ann. 2014;8(1).

- 37.Buchanan D, Fitzgerald L, Ketley D, et al. No going back: A review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int J Manag Rev. 2005;7(3):189–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrew B, Sutton Anthea PD. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review. SAGE Publications; 2016.

- 39.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, et al. Defining Cultural Competence: A Practical Framework for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Betancourt JR, Tan-McGrory A, Kenst KS, Phan TH, Lopez L. Organizational Change Management For Health Equity: Perspectives From The Disparities Leadership Program. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(6):1095–1101. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Quality Forum. A roadmap for promoting health equity and elimiting disparities. The Four I’s for Health Equity; 2017. http://www.qualityforum.org/Home.aspx. Accessed September 2017

- 43.Cattacin S, Chiarenza A, Domenig D. Equity standards for healthcare organisations: a theoretical framework. Divers Equal Heal Care. 2013;10(4):249–258. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castillo RJ, Guo KL. A framework for cultural competence in health care organizations. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2011;30(3):205–214. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e318225dfe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson-Robinson M, Reininger B, Sellers B, Saunders R, Davis K, Ureda J. Conceptual framework for the provision of culturally competent services in public health settings. J Cult Divers. 2006;13(2):97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyatt R, Laderman M, Botwinick L, Mate K, Whittington J. Acheiving Health Equity: A Guide for Healthcare Organizations. IHI White Paper. Cambridge; 2016. ihi.org. Accessed September 2017

- 47.Health Research Educational Trust. Equity of care: a toolkit for eliminating health care disparities ®. 2015.

- 48.Office of Minority Health. National standards for CLAS in health and health care: a blueprint for advancing and sustaining CLAS policy and practice. 2013. https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/pdfs/EnhancedCLASStandardsBlueprint.pdf#page82. Accessed September 2017

- 49.National Health Service. A refreshed equality delivery system for the NHS: EDS2 making sure that everyone counts. 2013. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/eds-nov131.pdf. Accessed September 2017

- 50.Rural and Regional Health and Aged Care Services. Cultural responsiveness framework. 2009. www.health.vic.gov.au/cald. Accessed September 2017

- 51.Laderman M, Whittington J. A Framework for improving Health Equity. Healthc Exec. 2016;31(3):82,84–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tynan M, Smullen F, Atkinson P, Stephens K. Aboriginal cultural competence for health services in regional Victoria: lessons for implementation. Aust New Zeal J Public Heal. 2013;37(4):392–393. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seeleman C, Essink-Bot M-L, Stronks K, Ingleby D. How should health service organizations respond to diversity? A content analysis of six approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:510. 10.1186/s12913-015-1159-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Batras D, Duff C, Smith BJ. Organizational change theory: implications for health promotion practice. Health Promot Int. 2014;129(5 Pt 1):dau098. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee S-YD. Review: Conceptualization and Measurement of Organizational Readiness for Change. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(4):379–436. doi: 10.1177/1077558708317802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chin MH, King PT, Jones RG, et al. Lessons for achieving health equity comparing Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States. Health Policy. 2018;0(0). 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LUScher LS, Lewis MW. Organizational Change and Managerial Sensemaking: Working Through Paradox. Acad Manag J. 2008;51(2):221–240. doi: 10.5465/amj.2008.31767217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parand A, Burnett S, Benn J, Pinto A, Iskander S, Vincent C. The disparity of frontline clinical staff and managers’ perceptions of a quality and patient safety initiative. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(6):1184–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diamond LC, Wilson-Stronks A, Jacobs EA. Do hospitals measure up to the national culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards? Med Care. 2010;48(12):1080–1087. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f380bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gómez ML, Charnigo R, Harris TT, Williams JC, Pfeifle W. Assessment of National CLAS Standards in Rural and Urban Local Health Departments in Kentucky. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(6):576–585. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weech-Maldonado R, Dreachslin JL, Brown J, et al. Cultural competency assessment tool for hospitals: evaluating hospitals’ adherence to the culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37(1):54–66. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31822e2a4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chin MH. Creating the Business Case for Achieving Health Equity. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):792–796. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3604-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0637-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]