INTRODUCTION

Working in global health is at once rewarding and challenging.1 Delivering healthcare to underserved populations can be isolating, demanding, and emotionally draining, particularly in resource-limited settings.2

Narrative medicine is defined as the practice of clinical medicine using narrative competence: the skillset necessary “to recognize, interpret, and be moved by stories of illness.”3 Teaching narrative skills to healthcare providers has been shown to foster wellbeing and reduce burnout.3, 4 One such skill, reflective writing, is most effective when explicit emotional disclosure is used.5 Global health is a potential niche for narrative training that has not been thoroughly explored.

The Health, Equity, Action, and Leadership (HEAL) Initiative is a 2-year, inter-professional global health fellowship. HEAL fellows engage in immersive clinical experiences at a variety of underserved sites, both locally and internationally. While they are encouraged to reflect about their experiences on an online blog (https://healinitiative.org/blog/), not everyone participates, and there is minimal formal training in reflective practice.

The goal of this study was to investigate the reflective practices and need for additional narrative training among global health fellows in the HEAL Initiative.

METHODS

Survey

All current HEAL fellows in 2018 (N = 60) were surveyed electronically using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) on the following 3 topics: interest in narrative training, current reflective practices, and perceived barriers to reflection.

Blog Review

A retrospective review of reflective blog posts written by current and former HEAL fellows between 13 August 2013 and 1 November 2017 was performed independently by three reviewers (ZGJ, KC, SDA). All coding discrepancies were resolved by negotiated consensus.

Each blog was rated deductively for 1 major theme and ≥ 1 minor themes. Reviewers used a pre-defined codebook of healthcare themes (Table 1), which was adapted from a previous study.6 A major theme was defined as representing the central, overarching subject of the reflection. Thematic content featured to any lesser degree was coded as a minor theme.

Table 1.

Themes Used in Deductive Analysis of Fellows’ Blog Posts

| Theme | |

|---|---|

| Humanism | |

| Professionalism | |

| Inter-professionalism | |

| Caregiving | |

| Learning/teaching | |

| Death and dying | |

| Personal wellbeing | |

| Healthcare systems | |

| Healthcare disparities | |

| Advocacy | |

| Ethics |

Reviewers also rated the degree of explicit emotional disclosure in each blog (none, low, or high). Blogs with no disclosure were purely expository. Blogs with low disclosure featured brief or superficial discussions of emotion, while those with high disclosure were defined as having frequent or in-depth discussions of emotion, or where emotion was the main focus of the narrative.

RESULTS

Survey

Forty-seven of 60 fellows (78%) responded to the survey. Forty-two (89%) reported desire for additional narrative training, while only 7 (15%) endorsed writing regularly at present. Common barriers included inadequate time (60%), lack of skill (55%), difficulty identifying a topic (26%), and embarrassment (17%).

Blog Review

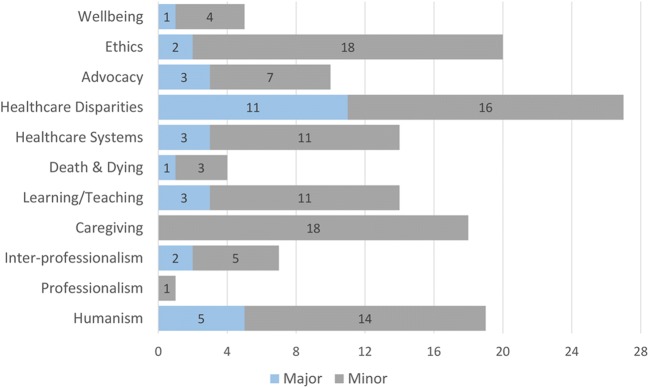

A total of 31 blog posts authored by 19 different fellows were reviewed. Results of thematic analysis are shown in Figure 1. Healthcare disparities was overall the most prominent theme, coded as the major theme in 11 blogs (36%) and the minor theme in 16 (58%). Themes of professionalism, death and dying, and wellbeing were relatively underrepresented. The majority of blog posts (22 [71%]) were rated as having no emotional disclosure, while only 4 (13%) featured the highest degree of disclosure.

Figure 1.

Frequency of major and minor themes identified in deductive content analysis of 31 reflective blog posts written by global health fellows.

DISCUSSION

Here, we demonstrate a need and desire for narrative training among our global health trainees. While 9 in 10 fellows expressed interest in a narrative medicine curriculum, only 1 in 6 endorsed writing reflectively on a regular basis. On review of historical reflections, we found a narrow thematic focus and paucity of emotional disclosure. Further, only a small subset of fellows contributed to the blog over the 4-year study period.

Global health poses unique challenges in delivering healthcare to the underserved. Narrative medicine represents an underutilized skillset for building resiliency among global health providers. Moving forward, we plan to implement a narrative medicine curriculum focusing on overcoming barriers to writing, broadening thematic content in reflections, and emboldening emotional disclosure and introspection. We encourage other global health programs to use these results to inform their own curricular innovations in an effort to foster wellbeing among their trainees.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of California, San Francisco Academy of Medical Educators Innovations in Medical Education Grant, which will be used to fund future curricular innovations related to this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Iserson KV, Biros MH, James Holliman C. Challenges in international medicine: ethical dilemmas, unanticipated consequences, and accepting limitations. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012;19:683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi AS, Selia E, McDonnell K. Stress and provider retention in underserved communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20:597–604. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charon R. Narrative medicine: form, function, and ethics. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen I, Forbes C. Reflective writing and its impact on empathy in medical education: systematic review. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. 2014;11:20. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baikie KA, Wilhelm K. Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11:338–346. doi: 10.1192/apt.11.5.338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer MA, Haley H-L, Saarinen CL, Chretien KC. Comparison of blogged and written reflections in two medicine clerkships. Med Educ. 2011;45:166–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]