INTRODUCTION

Work schedules for hospitalists appear to differ greatly, though the evidence is mostly anecdotal.1 Some schedules, such as seven or more consecutive days working, would promote continuity, while other schedules, like 12 h on and 36 off, would result in a hospitalized patient receiving care from multiple providers. In this paper, we describe individual hospitalist work schedules, and their association with continuity of care.

METHODS

We used 100% Texas Medicare claims data for January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2014. Hospitalists (n = 2334) were identified as generalist physicians with ≥ 80% of their total Evaluation and Management Medicare charges in 2014 for hospitalized patients.2 We counted each day a hospitalist billed for E&M services for a hospitalized fee-for-service Medicare patient as a working day. We calculated the percentage of each hospitalist’s total number of working days in 2014 that was part of a block of ≥ 3 or ≥ 5 or ≥ 7 consecutive working days. We also identified all admissions receiving generalist care from those hospitalists and determined the number of different hospitalists providing that care. In a multilevel model, we estimated the odds of a patient receiving all generalist care from just one hospitalist, as a function of the usual schedule of the admitting hospitalist, controlled for patient demographics, comorbidities, reason for hospitalization, and length of stay.

RESULTS

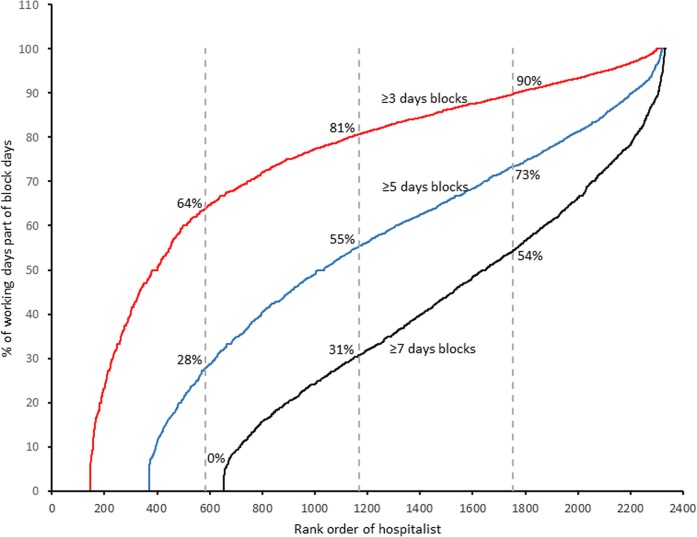

We categorized all Texas hospitalists by the percent of their total number of working days in 2014 that was part of a block of at least 3 or 5 or 7 consecutive working days. There was considerable heterogeneity. At one extreme, 147 (6.3%) hospitalists had no working days that were part of a 3-day or longer block. In contrast, 702 (30%) hospitalists had > 50% of their working days as part of a 7 or more day block (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of hospitalist working days that is part of a ≥ 3 or ≥ 5 or ≥ 7 block of consecutive working days. The figure ranks 2334 Texas hospitalists by the percentage of working days that was part of a block of ≥ 3 or ≥ 5 or ≥ 7 working days. The 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of hospitalists are indicated by vertical dotted lines. For example, 147 hospitalists (6%) had no block of 3 or more consective days of working; 1167 hospitalists (50%) spent at least 81% of their working days as part of a> 3-day block of consecutive working days; 370 hospitalists (16%) had no blocks of working five or more consecutive days; and 655 (28%) had no blocks of 7 or more days.

Table 1 presents the adjusted odds of a hospitalized patient receiving care from just one hospitalist, as a function of hospitalist work schedules. Patients receiving their initial care from hospitalists in the highest quartile for working in seven or more day blocks were more than five times as likely to experience continuity of care as those cared for by hospitalists in the lowest quartile (OR = 5.52, 95% CI 5.14, 5.92).

Table 1.

The Percent of Hospitalist Working Days That Were Part of a Block of 7 or More Consecutive Days, Stratified by the Work Schedule of the Hospitalists, and the Odds of Receiving Care from Only One Hospitalist During Hospitalization, Adjusted for Patient Characteristics. The Cohort Includes Medical Admissions in Texas Medicare Data in 2014 with a 3-, 4-, 5-, or 6-Day Length of Stay. Analyses Represent a Multilevel Model (Admission and Admitting Hospitalist), Stratified by the Work Schedule of the Hospitalist, and Adjusted for Patient Age, Gender, Race/Ethnicity, Residence Prior to Admission, Length of stay, Medicaid Eligibility, Number of Prior Hospitalizations, DRG-MDC for the Admission, and 31 Elixhauser Comorbidities in the Prior Year, Entered Separately. Similar Results Were Obtained in a Number of Sensitivity Analyses, Such as Including All Medical and Surgical Admissions with Any Length of Stay in the Cohort, and Excluding the Initial (Admitting) Evaluation and Management Charge in Determining the Number of Hospitalists Who Cared for the Patient).

| Quartile of hospitalist | N (%) of admissions | Observed rate | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (% of working days that was in a block of > 7 days) | 63,145 | 52.3% | |

| Q1 (= 0) | 9160 (14.5%) | 36.4% | Reference |

| Q2 (0 ≤ 31.1%) | 12,313 (19.5%) | 43.0% | 1.92 (1.78–2.07) |

| Q3 (31.1 ≤ 54.5%) | 16,535 (26.2%) | 54.7% | 3.10 (2.89–3.34) |

| Q4 (> 54.5%) | 25,137 (39.8%) | 61.1% | 5.52 (5.14–5.92) |

DISCUSSION

We found that hospitalist schedules vary widely, with a predictable association with inpatient continuity of care. On the other hand, hospitalist schedules with many consecutive working days may promote burnout3, 4 and inhibit gender equity.5 Decisions on hospitalist schedules must balance those competing priorities.6

Limitations of the study include the use of Texas data to describe hospitalist schedules. The distribution of hospitalist schedules shown in Figure 1 may not be the same in other states. Also, the measurements of hospitalist schedules and of continuity of care have inaccuracies. The method of determining hospitalist schedules cannot distinguish between, for example, a hospitalist working an 8-h daily shift for seven consecutive days from one who is on an every other night call shift, where each 8- or 12-h shift overlaps two consecutive calendar days. Also, hospitalists caring primarily for younger patients or HMO patients might not generate an E&M charge on a fee-for-service Medicare patient every day that they work, which would bias the estimate of their schedules. Similarly, the continuity of care measure cannot distinguish between discontinuities because a patient was admitted at night from a patient seeing a different physician each day. Nevertheless, the strong association between the measure of hospitalist schedules and the measure of inpatient continuity provides internal validation for both measures.

In conclusion, Medicare data may provide useful information on hospitalist schedules and inpatient continuity of care.

Author Contributions

Dr. Goodwin had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Goodwin, Kuo, Nattinger. Draft of the manuscript: Goodwin. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Goodwin, Kuo, Nattinger, Zhou. Statistical analysis: Zhou, Kuo. Obtained funding: Goodwin. Supervision: Goodwin. Registration: None.

Funders

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG33134 and K05 CA134923).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000—the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Eng L Med. 2009;360(11):1102–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simone KG. Hospitalist Recruitment and Retention Building Medicine Program. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachter RM. The hospitalist field turns 15: new opportunities and challenges. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:E1–4. doi: 10.1002/jhm.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1033–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Joint Commission Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. 2017;58(58):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]