Summary

• Oats produce avenacins, antifungal triterpenes that are synthesized in the roots and provide protection against take-all and other soilborne diseases. Avenacins are acylated at the carbon- 21 position of the triterpene scaffold, a modification critical for antifungal activity. We have previously characterized several steps in the avenacin pathway, including those required for acylation. However, transfer of the acyl group to the scaffold requires the C-21β position to be oxidized first, by an as yet uncharacterized enzyme.

• We mined oat transcriptome data to identify candidate cytochrome P450 enzymes that may catalyse C-21β oxidation. Candidates were screened for activity by transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana.

• We identified a cytochrome P450 enzyme AsCYP72A475 as a triterpene C-21β hydroxylase, and showed that expression of this enzyme together with early pathway steps yields C-21β oxidized avenacin intermediates. We further demonstrate that AsCYP72A475 is synonymous with Sad6, a previously uncharacterized locus required for avenacin biosynthesis. sad6 mutants are compromised in avenacin acylation and have enhanced disease susceptibility.

• The discovery of AsCYP72A475 represents an important advance in the understanding of triterpene biosynthesis and paves the way for engineering the avenacin pathway into wheat and other cereals for control of take-all and other diseases.

Keywords: Avena strigosa, avenacins, cytochromes P450, disease resistance, metabolic engineering, natural products, triterpenes

Introduction

Plants produce a wealth of diverse natural products. These compounds have important ecological roles, providing protection against pests and diseases. Oats (Avena spp.) are unusual amongst the cereals and grasses in that they produce antimicrobial triterpene glycosides (saponins) (Turner, 1960). Saponins are one of the largest families of plant natural products and are produced primarily by eudicots (Hostettmann & Marston, 1995). Previously we have shown that saponins produced in oat roots (avenacins) provide protection against soilborne pathogens such as Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, causal agent of take-all disease (Osbourn etal., 1994; Papadopoulou etal., 1999). Take-all causes major yield losses in wheat, with complete crop failure occurring under severe disease conditions. Disease severity increases with successive wheat cropping, and growth of second and third wheat crops in the same field can become economically unviable (Asher & Shipton, 1981; Hornby & Bateman, 1998). The problem is confounded by the fact that sources of genetic resistance to take-all disease have not yet been identified in hexaploid wheat germplasm (Scott etal., 1989; Freeman & Ward, 2004).

The most effective way to achieve simple, economic and sustainable control of take-all disease would be through genetic resistance. Oats have extreme resistance to G. graminis var. tritici and are used in rotation for take-all control. The major avenacin, A-1, fluoresces bright blue under ultraviolet illumination as a result of the presence of N-methyl anthranilate, which is attached at the carbon-21 position of the triterpene scaffold (Fig. 1a). Previously we exploited this property to screen for mutants of diploid oat (Avena strigosa) with reduced root fluorescence, and identified c. 100 avenacin-deficient mutants (Papadopoulou et al., 1999; Qi et al., 2006). These mutants have enhanced susceptibility to G. graminis var. tritici and other soilborne fungal pathogens, indicating that avenacins confer disease resistance (Papadopoulou et al., 1999; Mugford et al., 2013). We have subsequently characterized six steps in the avenacin pathway and have shown that the corresponding genes form part of a biosynthetic gene cluster (Haralampidis et al., 2001; Qi et al., 2004, 2006; Geisler et al., 2013; Mugford et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013; T. Louveau & A. Osbourn, unpublished). The avenacin gene cluster represents the only source of genetic resistance to take-all to be characterized from any cereal or grass species. Wheat and other cereals do not make avenacins, nor do they appear to make other triterpene glycosides. Characterization of the complete avenacin biosynthetic pathway would open up new opportunities for take-all control in wheat and other cereals using metabolic engineering approaches.

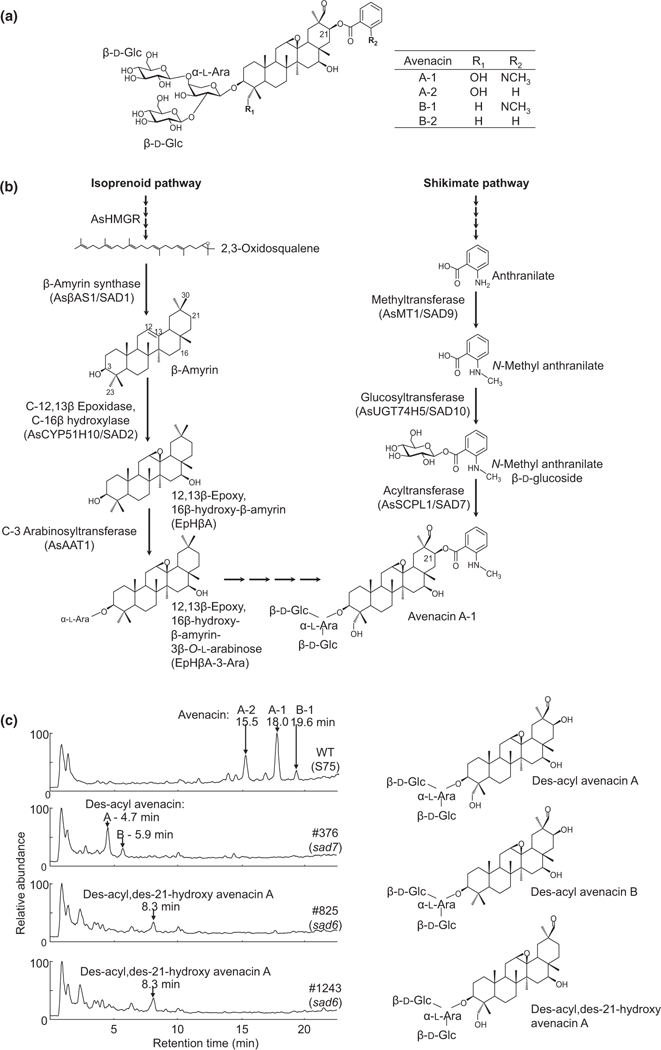

Fig. 1.

Identification of C-21β oxidase-deficient (sad6) oat mutants. (a) Structures of the four avenacins. Avenacin A-1 is the major avenacin found in oat roots. Avenacins A and B are differentiated by the presence (A) or absence (B) of a hydroxyl group at C-23 (R1). Avenacins A-1 and B-1 are acylated with N-methyl anthranilate at the C-21 position, and avenacins A-2 and B-2 have benzoate at this position (R2). AsHMGR, Avena strigosa HMG-CoA reductase. (b) Current understanding of the pathway for the biosynthesis of avenacin A-1. The triterpene scaffold originates from the isoprenoid pathway (left), and the N-methyl anthranilate acyl group from the shikimate pathway (right). (c) LC-MS analysis of root extracts of seedlings of the wild-type oat accession and sad6 and sad7 mutant lines. The major avenacin peaks (A-1, A-2 and B-2, 15.5–19.6 min) observed in the wild-type are absent in sad6 and sad7 mutants (the least abundant, B-2, was below the detection limit in these analyses). The sad7 mutants accumulate nonacylated avenacins (des-acyl-avenacins A and B) as previously reported (Mugford et al., 2009), owing to lack of the acyltransferase, AsSCPL1/SAD7. The sad6 mutants #825 and #1243 accumulate a form of nonacylated avenacin, putatively designated des-acyl, des-21-hydroxy-avenacin A (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

Oats produce four structurally related avenacins, A-1, B-1, A-2 and B-2 (Fig. 1a). The major avenacin found in oat roots is avenacin A-1. The first committed step in avenacin biosynthesis involves the cyclization of the linear isoprenoid precursor 2,3- oxidosqualene to the pentacyclic triterpene scaffold, β-amyrin. Conversion of β-amyrin to avenacins involves a series of oxygenation steps, addition of a trisaccharide chain at the C-3 position, and acylation at the C-21 position, shown for avenacin A- 1 in Fig. 1(b). Acylation of avenacin A-1 is carried out by the serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase AsSCPL1 (SAD7), which uses N-methylanthranilate glucoside generated via the shikimate pathway as the acyl donor (Mugford et al., 2009). We have previously shown that acylation is critical for antifungal activity (Mugford et al., 2013). The AsSCPL1/Sad7 acyltransferase gene is adjacent in the avenacin biosynthetic gene cluster to AsMT1/Sad9 and AsUGT74H5/Sad10, genes that together encode the enzymes necessary for the biosynthesis of the N-methylanthranilate glucoside acyl donor (Mugford et al., 2013). However, addition of the acyl group will depend on prior functionalization of the C-21 position of the triterpene scaffold by oxygenation. The enzyme that carries out this key step has not yet been characterized.

Here we identify the missing enzyme that carries out this important functionalization step, so paving the way for the union of the isoprenoid pathway-derived triterpene backbone and the shikimate acid pathway-derived acyl group (Fig. 1b). We show that this cytochrome P450 (CYP) (AsCYP72A475), catalyses C-21β hydroxylation of the avenacin triterpenoid backbone. To our knowledge, this is the first such triterpene C-21 oxidase to be described from monocots. We further demonstrate that AsCYP72A475 is encoded by the Sad6 locus, which forms part of the avenacin biosynthetic gene cluster, and show that AsCYP72A475 is critical for avenacin acylation and plant defence.

Materials and Methods

Oat material, metabolic profiling and disease assays

The wild-type diploid oat accession used in this study was Avena strigosa accession S75 (Papadopoulou et al., 1999). The A. strigosa mutant lines used in this study are described in Papadopoulou et al. (1999), Haralampidis et al. (2001), Qi et al. (2004) and Mugford et al. (2009). The LC-MS profiling methods used for analysis of root extracts of seedlings of wild-type and mutant oat lines are detailed in Supporting Information Methods S1. Take-all disease assays were performed as described previously, using Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici strain T5 (Papadopoulou et al., 1999).

Genetic linkage analysis

Avena atlantica accession Cc7277 (Institute of Biology, Environmental and Rural Sciences (IBERS) collection, Aberystwyth University, UK) was sequenced by Illumina technology to c. 38-fold coverage using paired-end and mate-pair libraries. Assembled contigs were then mapped by survey sequencing of recombinant inbred lines from a cross between Cc7277 and A. strigosa accession Cc7651 (IBERS) (R. Vickerstaff & T. Langdon, unpublished). Annotations of contigs linked to the previously identified avenacin biosynthetic genes were used to identify candidate CYP genes.

Generation of Gateway entry and expression constructs

Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and all PCR steps were performed using iProof™ High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Bio-Rad). Candidate CYP genes were identified by mining (using BLAST searches) a root tip transcriptome database for A. strigosa accession S75 that we generated previously (NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession ERA148431 (Kemen et al., 2014). A. strigosa root tip RNA was extracted from 5-d-old seedlings and cDNA synthesized as described previously (Kemen et al., 2014). PCR amplification of CYP candidate genes from root tip cDNA was carried out using the primers listed in Table S1 and the attB adapter PCR strategy described in the Gateway Technology manual (Invitrogen). The GenBank accession numbers for the full-length coding sequences of the oat candidate CYPs used in this work are CYP71E22 (MH539811), CYP72A475 (MH539812), CYP72A476 (MH539813), CYP88A75 (MH539814), CYP89N1 (MH539815), CYP706C45 (MH539816), and CYP711A54 (MH539817). The soybean GmCYP72A69 gene (accession NM_ 001354946) was synthesized commercially (Integrated DNA Technologies, Leuven, Belgium) with flanking Gateway attB sites.

Gateway Entry constructs were generated by cloning the amplified or synthetic gene products into the pDONR207 vector using BP clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the Entry clones was checked by Sanger sequencing (performed by GATC Biotech, Konstanz, Germany). Genes were cloned from the relevant Entry vectors into pEAQ-HT-DEST1 (Sainsbury et al., 2009) using the LR clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Lomonossoff laboratory (John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK) kindly provided us with an expression construct containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding sequence in pEAQ-HT-DEST1 (Sainsbury et al., 2009). Expression constructs were transformed into chemically competent cells of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 by flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Transient expression in N. benthamiana

Transformed A. tumefaciens strains carrying the relevant expression constructs were cultured and infiltrated into N. benthamiana using a syringe without a needle, as previously described (Sainsbury et al., 2012; Reed et al., 2017). Extraction of leaves and GC-MS analysis were performed as described previously (Reed et al., 2017). Methods used for LC analysis can be found in Supporting Information Methods S2.

AsCYP72A475 sequencing and gene expression analysis

Avena strigosa seedlings were grown as previously described (Papadopoulou et al., 1999). Genomic DNA was extracted from A. strigosa leaves using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Primers used for sequencing the AsCYP72A475 gene are listed in Table S2. For gene expression profiling by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR), shoots, whole roots, root tips (terminal 2–3 mm) and elongation zones (section of roots directly above the root tip, c. 4 mm long) of 5-d-old seedlings were harvested and RNA extracted using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase digestion (RG1; Promega). cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) with oligo dT primers. One microgram of total RNA from each tissue type was used per cDNA synthesis reaction. Primers for RT-PCR (Table S3) and qPCR analysis (Table S4) were designed using Primer3 (Untergasser et al., 2012). RT-PCR was performed using GoTaq Green polymerase (Promega) with a 55°C annealing temperature and 40 s elongation time over 30 cycles. PCR products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. For qPCR, samples were analysed in triplicate using the DYNAMO Flash SYBR Green kit (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR thermal cycling and analysis were performed using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection system. For all experiments, target amplification was measured using the ΔΔCq method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001) relative to the A. strigosa EF1-α gene (Kemen et al., 2014).

Phylogenetic analysis

CYP72A protein sequences used for phylogenetic analysis were from Prall et al. (2016), with additional inclusion of KpCYP72A397 from Kalopanax septemlobus (Han et al., 2018), OsCYP72A31 from rice (Saika et al., 2014), and the oat AsCYP72A475 CYP reported here. Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using MEGA 6 (Tamura et al., 2013). Sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) and neighbour joining (Saitou & Nei, 1987) was carried out using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton method (Jones et al., 1992) (with 1000 bootstrap replicates).

Purification and structural elucidation of 12,13-epoxy, 16,21-dihydroxy-β-amyrin-3-O-L-arabinose

Details of the purification process and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments are provided in Supporting Information Methods S3.

Results

Identification of C-21β oxidase-deficient (sad6) oat mutants

Previously, we reported the identification of two avenacin-deficient A. strigosa mutants #825 and #1243 that were initially assigned to separate loci (Papadopoulou et al., 1999; Qi et al, 2004) but that we have subsequently shown to be allelic. These mutants represent independent mutant alleles of Sad6, a locus that we have defined genetically but that has not yet been cloned and characterized. The Sad6 locus cosegregates with the other characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes and so is anticipated to be part of the biosynthetic gene cluster (Qi et al., 2004). Metabolite analysis of oat root extracts by LC-MS indicates that the avenacin-deficient sad6 mutants #825 and #1243 accumulate a new compound with a retention time of 8.3 min (Fig. 1c). sad7 mutants lack the acyltransferase needed for addition of the acyl group at the C-21β position (Fig. 1b) and so accumulate the nonacylated avenacins, des-acyl avenacins A and B (retention times 4.7 and 5.9 min, respectively) (Fig. 1c). The mass spectrum of the product observed for the sad6 mutants was similar to that of des-acyl avenacin B (Fig. S1), suggesting that the acyl group is also absent in mutants #825 and #1243. However, in-chamber fragmentation of the new compound revealed that it contained only three of the four hydroxyl groups found in avenacin A (Fig. S1). The absence of the C-21β hydroxyl group was considered most likely, given that this would prevent subsequent acylation and account for the observed masses. Hence the product was putatively designated des-acyl, des-21-hydroxy-avenacin A (Fig. S1).

Identification of candidate genes by transcriptome mining

Accumulation of des-acyl, des-21-hydroxy-avenacin A in sad6 mutants #825 and #1243 suggests that these lines may have undergone mutations in a gene encoding a β-amyrin C-21β oxidase, most likely a CYP. We therefore mined an oat root tip transcriptome database that we generated previously (SRA accession ERA148431; Kemen et al., 2014) (within which all six previously characterized avenacin genes are represented) for all predicted CYPs. Over 100 CYP sequences were identified. To prioritize these for functional analysis, we exploited the fact that the Sad6 locus is known to be genetically linked to the characterized avenacin genes (Qi et al., 2004). We used the sequences of the six previously characterized avenacin biosynthesis genes to mine genomic sequence data generated by survey resequencing of a diploid oat mapping population derived from a cross between two avenacin-producing diploids, A. strigosa (IBERS Cc7651) and A. atlantica (IBERS Cc7277). Within the contigs that we recovered, we identified a total of eight CYPs genes, including the previously characterized AsCYP51H10 (Sad2) gene (Qi et al., 2006; Geisler et al., 2013). The seven new A. strigosa CYP sequences were assigned to CYP clans and named by the Cytochrome P450 Nomenclature Committee following established convention (Nelson, 2006) (Fig. 2a).

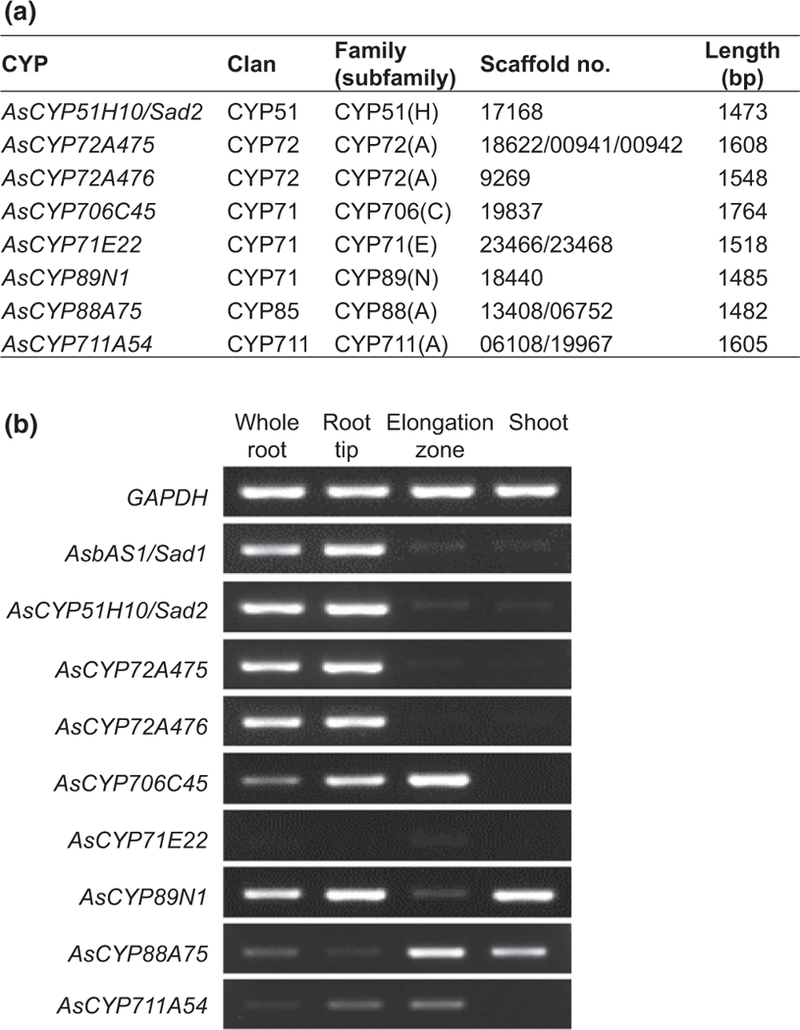

Fig. 2.

Candidate CYPs identified by transcriptome mining. (a) Root-expressed candidate CYPs identified in Avena strigosa. The corresponding scaffold names from the oat root transcriptome database (Kemen et al., 2014) are shown. (b) RT-PCR analysis of the transcript abundances of candidate CYP genes in different tissues from 3-d-old oat seedlings. Two previously characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes (AsbAS1/Sad1 and AsCYP51H10/Sad2) and the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH) are included as controls.

Expression of the previously characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes is restricted to the root tips, with little/no expression in other tissues (Haralampidis et al., 2001; Qi et al., 2006; Mugford et al., 2009, 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013; Kemen et al, 2014). We therefore investigated the expression profiles of our candidate CYP genes in different oat tissues by RT-PCR. Two of the previously characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes, AsbAS1/Sad1 and AsCYP51H10/Sad2, were included for comparison, along with the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Two of the seven new CYP genes (AsCYP72A475 and AsCYP72A476) had expression profiles that closely resembled those of the characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes (Fig. 2b), making them the most promising candidates for the C-21β hydroxylation step in avenacin biosynthesis.

AsCYP72A475 catalyses C-21β hydroxylation of the β-amyrin scaffold

Previously we showed that we could coexpress the first two steps in the avenacin pathway (β-amyrin synthase (AsbAS1/SAD1) and the CYP AsCYP51H10/SAD2) in N. benthamiana using transient plant expression and obtain the oxygenated avenacin pathway intermediate 12,13β-epoxy,16β-hydroxy-β-amyrin (EpHβA) (Geisler et al., 2013). Introduction of a third pathway enzyme (the oat arabinosyltransferase AsAAT1) into our coexpression experiments yields the C-3 arabinosylated form of EpHβA (EpHβA-3-Ara) (Fig. 1b) (T. Louveau and A. Osbourn, unpublished). Enhanced production of these compounds can be achieved using a feedback-insensitive version of the mevalonate pathway enzyme 3-hydroxy,3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (AstHMGR) (Reed et al., 2017). We therefore took advantage of this quick and efficient transient plant expression system to investigate whether any of the new candidate oat CYP enzymes were able to modify early avenacin pathway intermediates. The predicted full-length coding sequences of AsCYP72A475, AsCYP72A476 and three of the other new CYP genes (AsCYP706C45, AsCYP89N1 and AsCYP711A54) were amplified from an oat root tip cDNA library and cloned into the pEAQ-HT-DEST1 expression vector (Sainsbury et al., 2009). We were unable to clone the remaining two coding sequences, AsCYP71E22 and AsCYP88A75. The failure to amplify these genes is in accordance with our RT-PCR profile, which suggests low expression in root tips. Each of the five cloned candidates was evaluated for activity towards β-amyrin (by coexpression with AstHMGR and AsbAS1/Sad1), and EpHβA (by coexpression with AstHMGR, AsbAS1/Sad1 and AsCYP51H10/SAD2). N. benthamiana leaves were harvested 5 d after infiltration and leaf extracts were analysed by GC-MS. Of the five candidates tested, none had detectable activity towards β-amyrin (Fig. S2a). However, AsCYP72A475 was able to modify EpHβA when expressed in combination with AstHMGR, AsbAS1/SAD1 and AsCYP51H10/SAD2 to give a new peak at 14.9 min (Fig. 3a). No products were observed for the other CYP candidates (Fig. S2b). Analysis of the fragmentation pattern of the new compound was consistent with a putative identity of 12,13β-epoxy, 16β,21β-dihydroxy-β-amyrin (EpdiHβA) (Figs 3b, S3).

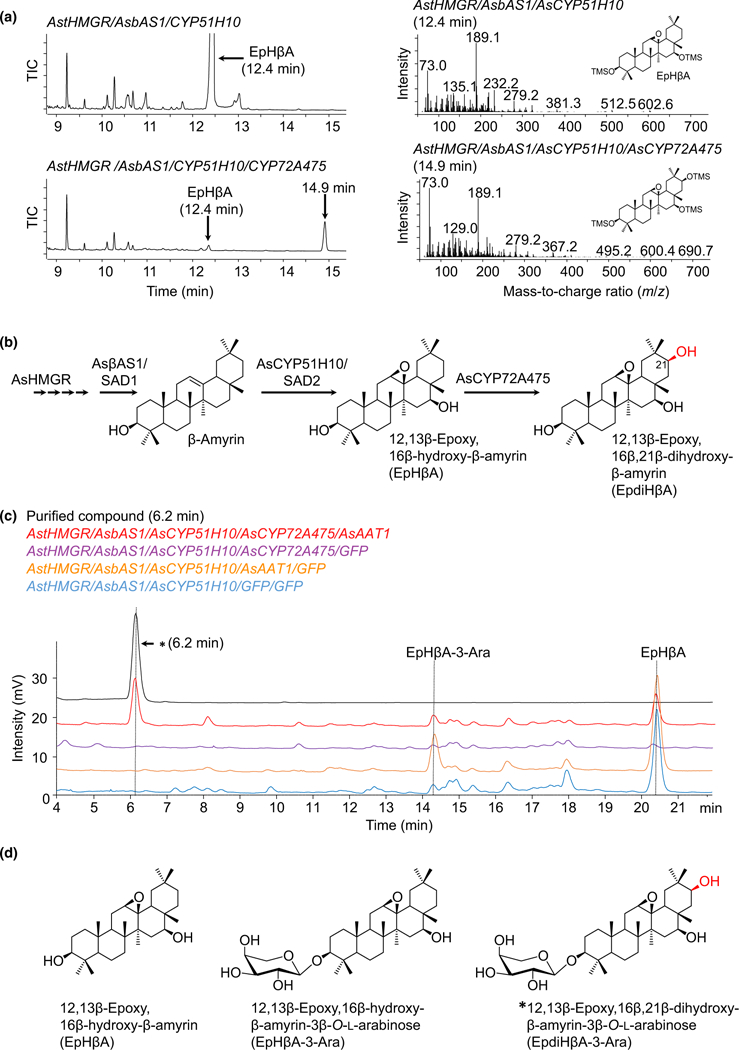

Fig. 3.

Production of EpdiHβA by transient expression of AsCYP72A475 in Nicotiana benthamiana. (a) GC-MS total ion chromatograms (TIC) of extracts from leaves expressing AstHMGR/AsbAS1/AsCYP51H10 alone or with AsCYP72A475. Mass spectra for 12,13β-epoxy-16β-hydroxy-β-amyrin (EpHβA, 12.4 min) and the novel peak putatively identified as 12,13β-epoxy, 16β,21β-dihydroxy-β-amyrin (EpdiHβA, 14.9 min) are shown on the right. Spectra are provided in Supporting Information Fig. S3. (b) Proposed pathway for biosynthesis of EpdiHβA from β-amyrin in N. benthamiana. (c) LC-charged aerosol detection chromatograms of extracts from leaves transiently expressing AstHMGR, AsbAS1 and AsCYP51H10 with different combinations of AsCYP72A475 and the C-3 arabinosyltransferase, AsAAT1. Upon coexpression of all enzymes, a novel peak was observed at 6.2 min (marked with an asterisk). (d) Structure of the purified compound with retention time 6.2 min (c) as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (further details provided in Fig. S4). AsHMGR and AstHMGR, Avena strigosa wild-type and feedback-insensitive HMG-CoA reductase, respectively (Reed etal., 2017).

We then attempted to isolate the product generated by AsCYP72A475 by scaling up our N. benthamiana experiments using vacuum infiltration (Reed et al., 2017). Unfortunately, despite repeated attempts, we were unable to isolate this product with a purity suitable for NMR analysis. However, inclusion of the avenacin C-3 arabinosyltransferase (AsAAT1) (T. Louveau & A. Osbourn, unpublished) in our coexpression experiments led to accumulation of a new compound with a retention time of 6.2 min (Fig. 3c) that proved to be more amenable to purification. Consequently, we chose this combination for large-scale infiltration. A total of 81.4 mg of this new product was purified. Subsequent NMR analysis confirmed that the structure of this product was consistent with it being 12,13β-epoxy,16β,21β-dihydroxy-β-amyrin-3β-O-L-arabinose (EpdiHβA-3-Ara) (Figs 3d, S4). Collectively, our data indicate that AsCYP72A475 is a C-21β hydroxylase.

Transient coexpression of the three genes required for avenacin A-1 acylation (AsSCPL1, AsMT1 and AsUGT74H5) together with AstHMGR, AsbAS1/SAD1, AsCYP51H10/SAD2, AsCYP72A475 and AsUGT99D1 in N. benthamiana yielded EpdiHβA-3-Ara and the acyl donor N-methyl anthranilate β-D-glucoside, but we were unable to detect any acylated triterpene. We have previously shown that the AsSCPL1, AsMT1 and AsUGT74H5 proteins are correctly processed and functional when transiently expressed in N. benthamiana (Mugford et al., 2009, 2013). Hence this may suggest that additional modifications to the triterpene scaffold are required before acylation can occur. Alternatively it is possible that any acylated product is also further modified by N, benthamiana endogenous enzymes to another product that we could not identify.

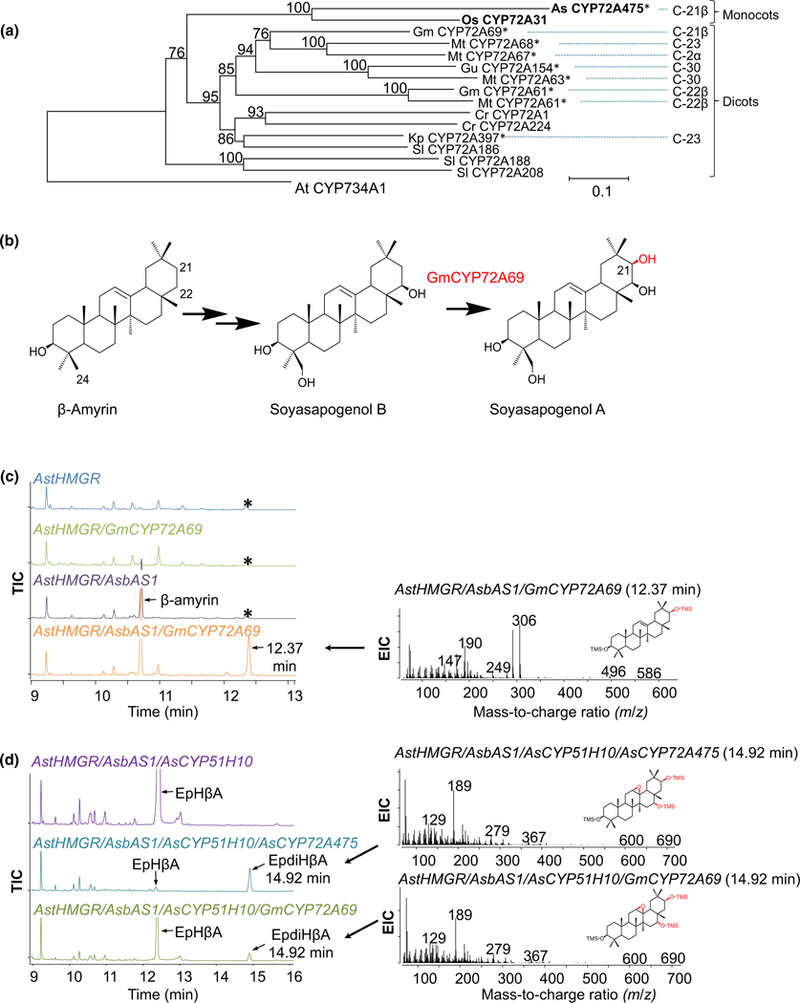

Phylogenetic and comparative analysis of CYP72A family members

AsCYP72A475 belongs to the CYP72 clan of the CYP superfamily (Nelson, 2006). Although the CYP72 clan is one of the largest groups of plant CYPs (Nelson & Werck-Reichhart, 2011; Ham-berger & Bak, 2013; Prall et al., 2016), relatively little is known about the functions of CYP72 enzymes (Irmler et al., 2000; Seki et al., 2011; Fukushima et al., 2013; Itkin et al., 2013; Miettinen et al., 2014; Saika et al., 2014; Biazzi et al., 2015; Umemoto et al., 2016; Yano et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018). The only previously characterized CYP72A enzyme from monocots is CYP72A31 from rice, which functions in inactivation of an acetolactate synthase-inhibiting herbicide (Saika et al., 2014). Characterized CYP72A enzymes from eudicots include those required for secaloganin biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus (CYP72A1 and CYP72A224) (Irmler et al., 2000; Miettinen et al., 2014), steroidal glycoalkaloid biosynthesis in tomato and potato (CYP72A186, CYP72A188 and CYP72A208) (Itkin et al., 2013; Umemoto et al., 2016) and several triterpene oxidases that modify various positions around the triterpene scaffold (Seki et al., 2011; Fukushima et al., 2013; Biazzi et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018). One of these (GmCYP72A69 from soybean) has recently been reported to oxygenate the triterpene soy-asapogenol B at the C-21β position (Fig. 4a) (Yano et al., 2017). The oat AsCYP72A475 CYP groups with the rice CYP72A31 enzyme in phylogenetic analysis in a subclade that is distinct from the characterized eudicot CYP72As (Fig. 4b). When the soybean enzyme GmCYP72A69 was coexpressed with AstHMGR and AsbAS1/SAD1 in N. benthamiana, a product with a retention time of 12.37 min and a mass spectrum consistent with that of 21-hydroxy-β-amyrin was detected (Fig. 4c). Hence GmCYP72A69, unlike AsCYP72A475, is able to oxygenate β-amyrin directly. In contrast, coexpression of GmCYP72A69 with AstHMGR, AsbAS1/SAD1 and AsCYP51H10/SAD2 yielded only low levels of EpdiHβA relative to EpHβA when compared with AsCYP72A475 (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic and comparative analysis. (a) Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree of 16 functionally characterized angiosperm CYP72A enzymes (Irmler et al., 2000; Seki et al., 2011; Fukushima et al., 2013; Itkin et al., 2013; Miettinen et al., 2014; Saika et al., 2014; Biazzi et al., 2015; Umemoto et al., 2016; Han et al., 2018; Yano et al., 2017; this work). Branch lengths represent number of amino acid substitutions per site (scale bar shown at bottom). Bootstrap support is given as percentages (1000 replicates) next to the branches. The tree is rooted using the (nonCYP72) Arabidopsis thaliana CYP734A1 enzyme, as previously described (Prall et al., 2016). Monocot sequences are indicated in bold. The eudicot CYP72A family members known to oxidize b-amyrin (or derivatives of β-amyrin) are marked with asterisks and the carbon position that these enzymes modify are showed on the right. As, Avena strigosa; At, A. thaliana; Cr, Catharanthus roseus; Gm, Glycine max; Gu, Glycyrrhiza uralensis; Kp, Kalopanax septemlobus; Mt, Medicago truncatula; Os, Oryza sativa; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum. (b) The soybean GmCYP72A69 has previously been reported to oxidize the β-amyrin-derived scaffold soyasapogenol B at the C-21β position to produce soyasapogenol A (Yano et al., 2017). (c) Coexpression of soybean GmCYP72A69 with AstHMGR and AsbAS1 results in a new peak (12.37 min), which was putatively identified as 21β-hydroxy-β-amyrin. A representative mass spectrum for the putative 21β-hydroxy-β-amyrin is given on the right. The mass spectrum for a minor coeluting product (labelled * in the controls) is shown in Supporting Information Fig. S5. (d) Coexpression of GmCYP72A69 with AstHMGR, AsbAS1 and AsCYP51H10 results in accumulation of a novel product (14.92 min) with a matching retention time and mass spectrum to EpdiHβA, as produced by coexpression of AstHMGR, AsbAS1, AsCYP51H10 and AsCYP72A475. AstHMGR, feedback-insensitive A. strigosa HMG-CoA reductase (Reed et al., 2017).

AsCYP72A475 is synonymous with Sad6

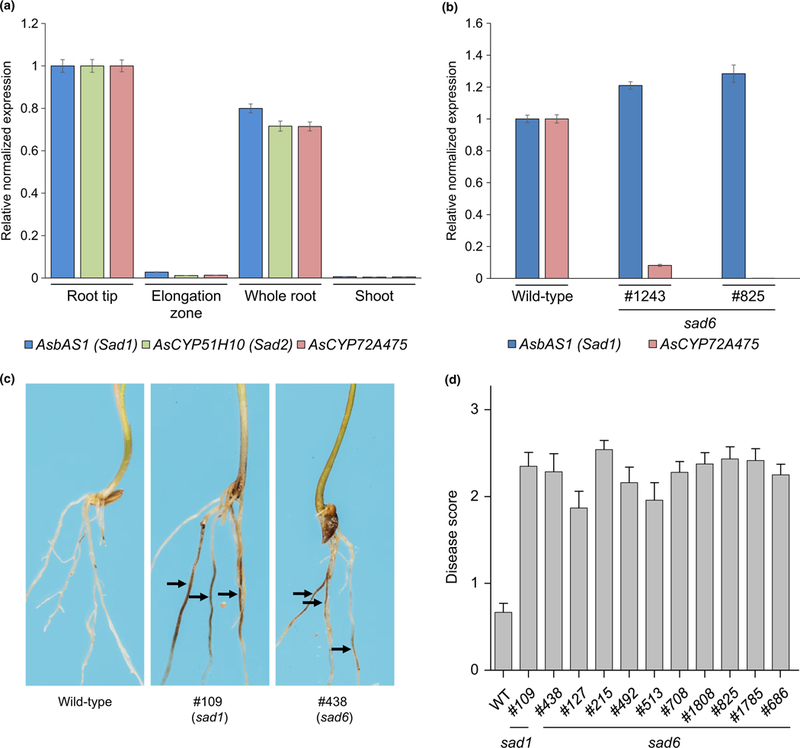

AsCYP72A475, like the other characterized avenacin biosynthesis genes, is expressed primarily in the root tips of wild-type A. strigosa seedlings, with little or no expression in other tissues (Figs 2b, 5a). The transcript abundance of this gene was substantially reduced/undetectable in the roots of seedlings of the two sad6 mutants, #1243 and #825 (Fig. 5b). DNA sequence analysis revealed a predicted stop codon in AsCYP72A475 at nucleotide 2772 in mutant #1243, suggesting that the reduced transcript abundances in this line may be attributable to nonsense-mediated RNA decay (Chiba & Green, 2009; Christie et al., 2011). Despite numerous attempts, we were unable to amplify the AsCYP72A475 gene from genomic DNA of mutant #825. This is consistent with our failure to detect any transcript for AsCYP72A475 in this line by qPCR (Fig. 5b), possibly owing to rearrangement or deletion in this region.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of Ascyp72a475 (sad6) mutants. (a) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of transcript abundances of AsbAS1/Sad1, AsCYP51H10/Sad2 and AsCYP72A475 in RNA extracted from 3-d-old Avena strigosa seedlings. (b) qRT-PCR analysis of AsCYP72A475 transcript abundances in RNA extracted from roots of wild-type and sad6 mutant lines. Expression levels are shown relative to the wildtype. All qPCR data transcript abundances were normalized to those for the elongation factor 1 (EF1-α) housekeeping gene, using the ΔΔCq method (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001). Values are means ± SE (three technical replicates). (c) Representative roots of wild-type, sad1 and sad6 A. strigosa lines following inoculation with the take-all fungus (Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici strain T5). Roots were scored based on presence and extent of lesions (arrows) as previously described (Papadopoulou et al., 1999). (d) Disease scores for a suite of sad6 mutant lines (Supporting Information Fig. S7a) compared with those of the wild-type (S75) and a susceptible sad1 mutant line (#109). The bars represent mean disease scores (21–25 seedlings per line). Error bars represent the SE of the mean.

Analysis of a further 55 additional uncharacterized avenacin-deficient mutants from our collection by LC-MS coupled with fluorescence detection (LC-MS-Fluo) identified 12 more mutants that, like #1243 and #825, accumulate des-acyl,des-21- hydroxy avenacin A-1 and B-1 (Fig. S6). DNA sequence analysis revealed that these lines also have mutations in the AsCYP72A475 gene (Fig. S7; Supporting Information Methods S4). These lines, like #1243 and #825 (Papadopoulou et al., 1999), also have increased susceptibility to take-all disease (Fig. 5c). Collectively our data show that AsCYP72A475 is synonymous with Sad6, and that this CYP is required for C-21β hydroxylation of the avenacin scaffold. This modification is required for acylation and hence for plant defence.

Discussion

Biosynthesis of the major avenacin, A-1, requires the concerted action of two pathways: the isoprenoid pathway, which supplies the triterpene backbone, and the shikimate pathway, which supplies the acyl moiety (Fig. 1b). Here we report the discovery and characterization of AsCYP72A745, a CYP that oxygenates the C- 21 position of the triterpene scaffold, so paving the way for avenacin acylation. The AsCYP72A475 gene is synonymous with Sad6, a locus that we previously identified in a forward screen for avenacin-deficient mutants. In earlier work we showed that transient expression of the anthranilate N-methyltransferase AsMT1 (encoded by Sad9) with the glucosyltransferase AsUGT74H5 (Sad10) in N. benthamiana leads to accumulation of N-methyl anthraniloyl-O-Glucose (NMA-glc), the acyl donor needed for addition of the N-methyl anthranilate group (Mugford et al., 2013). We also showed that the acyl transferase that mediates this process, the serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase AsSCPL1 (SAD7), can be expressed in N. benthamiana and that this heterologously expressed enzyme is functional (Mugford et al., 2009). However, when we coexpressed AstHMGR, AsbAS1/ SAD1, AsCYP51H10/SAD2, AsAAT1 and AsCYP72A475 together with these three enzymes, we were able to detect EpdiHβA-3-Ara and the acyl donor N-methyl anthraniloyl-O-Glc, but not acylated EpdiHβ−3-Ara. This is not surprising, given that AsSCPL1 is localized in the vacuole (the site of avenacin acylation), while the other characterized pathway enzymes are either known or predicted to be cytosolic (Mugford et al., 2013). Thus, further modification of the avenacin backbone by oxygenation and glycosylation is likely to be needed before transport to the vacuole, and potentially also one or more vacuolar transporter proteins. Future investigations will focus on identification of the missing steps in the avenacin biosynthetic pathway with the aim of reconstituting the entire pathway in N. benthamiana, and ultimately in major crops such as wheat.

Oxidation plays a critical role in natural product biosynthesis, furnishing functional groups that allow further elaboration of scaffold molecules through processes such as glycosylation and acylation. CYPs are therefore key drivers of metabolic diversification. C-21-oxidized β-amyrin-derived (oleanane-type) triterpenes are common in the plant kingdom (Vincken et al., 2007), and acylation at this position is prevalent within certain plant families (Lacaille-Dubois et al., 2011). C-21β acylation is critical for the antifungal activity of avenacins (Mugford et al., 2013). Acylation of other triterpenoids at this position is also known to determine cytotoxicity towards cancer cells (Chan, 2007). The numbers of characterized triterpene-modifying CYPs is continuing to grow (Thimmappa et al., 2014; Seki et al., 2015; Ghosh, 2017), and as it becomes possible to selectively oxygenate triterpene scaffolds at different carbon positions, this will create opportunities for metabolic engineering of this important family of natural products for diverse applications. The number of characterized triterpene-modifying acyltransferases (SCPL-like enzymes and BAHD acyltransferases) is currently very limited (Mugford et al., 2009; Shang et al., 2014). However, this is likely to change as the rapidly increasing body of genome sequence data available for diverse plant species continues to expand. The tendency of genes for different triterpene biosynthetic pathways to be clustered in plant genomes, as is the case for the oat avenacin pathway and for pathways for the biosynthesis of triterpenes associated with bitterness in the Cucurbitaceae (Qi et al., 2004; Mugford et al., 2013; Shang et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2016), is already facilitating the discovery of genes for new candidate triterpene-modifying CYPs, acyltransferases and other tailoring enzymes based on proximity to triterpene synthase genes (Field & Osbourn, 2008; Boutanaev et al., 2015).

To our knowledge, the oat AsCYP72A475 is the first C-21β triterpene oxidase to be reported from monocots. A second plant β-amyrin C-21β oxidase, GmCYP72A69, was recently reported from soybean (Yano et al., 2017). Both enzymes belong to the CYP72A subfamily of the CYP72 clan. Several CYP72A subfamily members have recently been characterized from eudicots (from the Fabaceae and Araliaceae families) and shown to be triterpene oxidases (Seki et al., 2011; Fukushima et al., 2013; Biazzi et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018). A recent large-scale analysis of angiosperm CYP72As showed that the Poales CYP72As form a distinct monophyletic group (Prall et al., 2016). Likewise, our analysis showed that AsCYP72A475 grouped with the rice OsCYP72A31 in a separate clade to the soybean C-21 oxidase GmCYP72A69 (Fig. 4a). Further transient expression experiments with the two C-21 oxidases suggested distinct differences in relative activity towards different substrates, β-amyrin and EpHpA. While the soybean GmCYP72A69 readily oxidized β-amyrin (Fig. 4c), the oat AsCYP72A475 appeared to be inactive towards this substrate (Fig. S2a). Conversely, GmCYP72A69 showed relatively poor activity towards EpHβA, while CYP72A475 resulted in near-total conversion to EpdiHβA (Fig. 4d). The ability of CYP72A enzymes to oxidize triterpenes is reported to have evolved multiple times in a lineage-specific manner in eudicots (Prall et al., 2016). Given that AsCYP72A475 and GmCYP72A69 share only 46% amino acid identity, the ability to oxidize the C-21β position of triterpene scaffolds may have arisen independently in oat and soybean. However, our phylogenetic analysis cannot rule out the possibility that the oat and soybean CYP72s may have shared a common ancestor with a role in triterpene biosynthesis. This might suggest that the shared C-21 oxidase activity of AsCYP72A475 and GmCYP72A69 represents a case of parallel rather than convergent evolution. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the enzymes catalysing the early steps of triterpene biosynthesis in oat (SAD1/AsbAS and SAD2/CYP51H10) appear to have evolved independently of those in eudicots (Haralampidis et al., 2001; Qi et al., 2006). Knowledge of the differences and parallels in triterpene biosynthesis between monocots and eudicots will facilitate our ability to identify additional triterpene biosynthetic enzymes. Understanding the differences in activity displayed by such enzymes will better inform strategies for optimizing triterpene biosynthesis in heterologous hosts. Collectively our findings represent an important advance in understanding triterpene biosynthesis and will underpin strategies for metabolic engineering for crop protection, drug development, and other industrial applications.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra for unacylated avenacins detected in roots of Avena strigosa avenacin-deficient mutants shown in Fig. 1(c). Fig. S2 GC-MS total ion chromatograms (TIC) from analysis of extracts of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves expressing AstHMGR and AsbAS1, or AstHMGR, AsbAS1 and AsCYP51H10 with candidate CYPs. Fig. S3 Electron-impact mass spectra for 12,13β-epoxy-16bhydroxy-β-amyrin (EpHβA) and putative 12,13β-epoxy-16,21βhydroxy-β-amyrin (EpdiHbA). Fig. S4 NMR assignment for 12,13β-epoxy,16β,21β-dihydroxyb-amyrin-3β-O-L-arabinose. Fig. S5 Electron-impact mass spectra for the product coeluting with 21-hydroxy-β-amyrin. Fig. S6 Identification of additional AsCYP72A475 (sad6) mutants by LC-MS metabolic profiling. Fig. S7 Schematic of AsCYP72A475 and mutation sites in sad6 mutants. Methods S1 Metabolite extraction, LC-MS-MS and LC-MSFluorescence analysis of oat roots. Methods S2 Metabolite extraction and LC-MS-CAD analysis of extracts of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Methods S3 Purification and structural elucidation of 12,13-epoxy,16,21-dihydroxy-β-amyrin-3-O-L-arabinose. Methods S4 Structural analysis of AsCYP72A475. Table S1 Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for Gateway cloning of coding sequences of the candidate CYP genes. Table S2 Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for sequencing of the genomic DNA region encoding for the Sad6 gene. Table S3 Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for RT-PCR expression profiling of the candidate CYPs from Avena strigosa. Table S4 Oligonucleotide primer sequences Primers used for quantitative PCR expression profiling of Avena strigosa CYPs.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lionel Hill and Paul Brett of the John Innes Metabolite Services for assistance in metabolite analysis. We would also like to thank Andrew Davis for photography and Thomas Louveau for assistance with extraction and purification methods used for EpdiHβA-3-Ara. This work was supported by BBSRC grants BB/E009912/1 (STM, AO), BB/K005952/1 (AL, AO) BB/H009582/1 LINK (TL), BB/H009582/1 and BBS/E/ W/0012843B (TL, RV), a National Institutes of Health Genome to Natural Products Network award U101GM110699 (JR, AO), the joint Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council/ Biotechnological and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC)-funded OpenPlant Synthetic Biology Research Centre grant BB/L014130/1 (MS, AO), Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program 2016QNRC001 by Chinese Association for Science and Technology (CAST) and State Scholarship Fund by China Scholarship Council (XQ), the BBSRC-funded Institute Strategic Programme Grant ‘Molecules from Nature’ (BB/P012523/1) and the John Innes Foundation. OpenPlant is joint-funded by the BBSRC and the EPSRC.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

References

- Asher MJC, Shipton PJ. 1981. Biology and control of take-all. London, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biazzi E, Carelli M, Tava A, Abbruscato P, Losini I, Avato P, Scotti C, Calderini O. 2015. CYP72A67 catalyzes a key oxidative step in Medicago truncatula hemolytic saponin biosynthesis. Molecular Plant 8: 1493–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutanaev AM, Moses T, Zi J, Nelson DR, Mugford ST, Peters RJ, Osbourn A. 2015. Investigation of terpene diversification across multiple sequenced plant genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112: E81–E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PK. 2007. Acylation with diangeloyl groups at C21–22 positions in triterpenoid saponins is essential for cytotoxicity towards tumor cells. Biochemical Pharmacology 73: 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Green PJ. 2009. mRNA degradation machinery in plants. Journal of Plant Biology 52: 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Christie M, Brosnan CA, Rothnagel JA, Carroll BJ. 2011. RNA decay and RNA silencing in plants: competition or collaboration? Frontiers in Plant Science 2: 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field B, Osbourn AE. 2008. Metabolic diversification — independent assembly of operon-like gene clusters in different plants. Science 320: 543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Ward E. 2004. Gaeumannomyces graminis, the take-all fungus and its relatives. Molecular Plant Pathology 5: 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima EO, Seki H, Sawai S, Suzuki M, Ohyama K, Saito K, Muranaka T. 2013. Combinatorial biosynthesis of legume natural and rare triterpenoids in engineered yeast. Plant Cell Physiology 54: 740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler K, Hughes RK, Sainsbury F, Lomonossoff GP, Rejzek M, Fairhurst S, Olsen CE, Motawia MS, Melton RE, Hemmings AM et al. 2013. Biochemical analysis of a multifunctional cytochrome P450 (CYP51) enzyme required for synthesis of antimicrobial triterpenes in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110: E3360–E3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S 2017. Triterpene structural diversification by plant cytochrome P450 enzymes. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger B, Bak S. 2013. Plant P450s as versatile drivers for evolution of species-specific chemical diversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences 368: 20120426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Chun JH, Oh SA, Park SB, Hwang HS, Lee H, Choi YE. 2018. Transcriptomic analysis of Kalopanax septemlobus and characterization of KsBAS, CYP716A94, and CYP72A397 genes involved in hederagenin saponin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiology 59: 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralampidis K, Bryan G, Qi X, Papadopoulou K, Bakht S, Melton R, Osbourn A. 2001. A new class of oxidosqualene cyclases directs synthesis of antimicrobial phytoprotectants in monocots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 98: 13431–13436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornby D, Bateman GL. 1998. Take-all disease of cereals: a regional perspective. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Hostettmann K, Marston A. 1995. Saponins. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irmler S, Schröder G, St-Pierre B, Crouch NP, Hotze M, Schmidt J, Strack D, Matern U, Schröder J. 2000. Indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus: new enzyme activities and identification of cytochrome P450 CYP72A1 as secologanin synthase. Plant Journal 24: 797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itkin M, Heinig U, Tzfadia O, Bhide AJ, Shinde B, Cardenas PD, Bocobza SE, Unger T, Malitsky S, Finkers R et al. 2013. Biosynthesis of antinutritional alkaloids in solanaceous crops is mediated by clustered genes. Science 341: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Computer Applications in the Biosciences 8: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemen AC, Honkanen S, Melton RE, Findlay KC, Mugford ST, Hayashi K, Haralampidis K, Rosser SJ, Osbourn A. 2014. Investigation of triterpene synthesis and regulation in oats reveals a role for β-amyrin in determining root epidermal cell patterning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111: 8679–8684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacaille-Dubois M-A, Pegnyemb DE, Noté OP, Mitaine-Offer A-C. 2011. A review of acacic acid-type saponins from Leguminosae-Mimosoideae as potent cytotoxic and apoptosis inducing agents. Phytochemistry Reviews 10: 565–584. [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen K, Dong L, Navrot N, Schneider T, Burlat V, Pollier J, Woittiez L, van der Krol S, Lugan R, Ilc T et al. 2014. The seco-iridoid pathway from Catharanthus roseus. Nature Communications 5: 3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugford ST, Louveau T, Melton R, Qi X, Bakht S, Hill L, Tsurushima T, Honkanen S, Rosser SJ, Lomonossoff GP et al. 2013. Modularity of plant metabolic gene clusters: a trio of linked genes that are collectively required for acylation of triterpenes in oat. Plant Cell 25: 1078–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugford ST, Qi X, Bakht S, Hill L, Wegel E, Hughes RK, Papadopoulou K, Melton R, Philo M, Sainsbury F et al. 2009. A serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase is required for synthesis of antimicrobial compounds and disease resistance in oats. Plant Cell 21: 2473–2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, Werck-Reichhart D. 2011. A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant Journal 66: 194–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR. 2006. Cytochrome P450 nomenclature, 2004. Methods in Molecular Biology 320: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbourn AE, Clarke BR, Lunness P, Scott PR, Daniels MJ. 1994. An oat species lacking avenacin is susceptible to infection by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 45: 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Owatworakit A, Townsend B, Louveau T, Jenner H, Rejzek M, Hughes RK, Saalbach G, Qi X, Bakht S, Roy AD et al. 2013. Glycosyltransferases from oat (Avena) implicated in the acylation of avenacins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 288: 3696–3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou K, Melton RE, Leggett M, Daniels MJ, Osbourn AE. 1999. Compromised disease resistance in saponin-deficient plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 96: 12923–12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prall W, Hendy O, Thornton LE. 2016. Utility of a phylogenetic perspective in structural analysis of CYP72A enzymes from flowering plants. PLoS ONE 11: e0163024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Bakht S, Leggett M, Maxwell C, Melton R, Osbourn A. 2004. A gene cluster for secondary metabolism in oat: implications for the evolution of metabolic diversity in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101: 8233–8238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Bakht S, Qin B, Leggett M, Hemmings A, Mellon F, Eagles J, Werck-Reichhart D, Schaller H, Lesot A et al. 2006. A different function for a member of an ancient and highly conserved cytochrome P450 family: from essential sterols to plant defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 103: 18848–18853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J, Stephenson MJ, Miettinen K, Brouwer B, Leveau A, Brett P, Goss RJM, Goossens A, O’Connell MA, Osbourn A. 2017. A translational synthetic biology platform for rapid access to gram-scale quantities of novel drug-like molecules. Metabolic Engineering 42: 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika H, Horita J, Taguchi-Shiobara F, Nonaka S, Nishizawa-Yokoi A, Iwakami S, Hori K, Matsumoto T, Tanaka T, Itoh T et al. 2014. A novel rice cytochrome P450 gene, CYP72A31, confers tolerance to acetolactate synthase-inhibiting herbicides in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 166: 1232–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury F, Saxena P, Geisler K, Osbourn A, Lomonossoff GP. 2012. Using a virus-derived system to manipulate plant natural product biosynthetic pathways. Methods in Enzymology 517: 185–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury F, Thuenemann EC, Lomonossoff GP. 2009. pEAQ: versatile expression vectors for easy and quick transient expression of heterologous proteins in plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal 7: 682–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The Neighbor-Joining method - a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott PR, Hollins TH, Summers RW. 1989. Breeding for resistance to two soil-borne diseases of cereals. Vorträge fur Pflanzenzüchtung 16: 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Seki H, Sawai S, Ohyama K, Mizutani M, Ohnishi T, Sudo H, Fukushima EO, Akashi T, Aoki T, Saito K et al. 2011. Triterpene functional genomics in licorice for identification of CYP72A154 involved in the biosynthesis of glycyrrhizin. Plant Cell 23: 4112–4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki H, Tamura K, Muranaka T. 2015. P450s and UGTs: key players in the structural diversity of triterpenoid saponins. Plant Cell Physiology 56: 1463–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Ma Y, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Duan L, Chen H, Zeng J, Zhou Q, Wang S, Gu W et al. 2014. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber. Science 346: 1084–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimmappa R, Geisler K, Louveau T, O’Maille P, Osbourn A. 2014. Triterpene biosynthesis in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 65: 225–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner EMC. 1960. The nature of the resistance of oats to the take-all fungus. 3. Distribution of the inhibitor in oat seedlings. Journal of Experimental Botany 11: 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto N, Nakayasu M, Ohyama K, Yotsu-Yamashita M, Mizutani M, Seki H, Saito K, Muranaka T. 2016. Two cytochrome P450 monooxygenases catalyze early hydroxylation steps in the potato steroid glycoalkaloid biosynthetic pathway. Plant Physiology 171: 2458–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. 2012. Primer3 — new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Research 40: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincken JP, Heng L, de Groot A, Gruppen H. 2007. Saponins, classification and occurrence in the plant kingdom. Phytochemistry 68: 275–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano R, Takagi K, Takada Y, Mukaiyama K, Tsukamoto C, Sayama T, Kaga A, Anai T, Sawai S, Ohyama K et al. 2017. Metabolic switching of astringent and beneficial triterpenoid saponins in soybean is achieved by a loss-of-function mutation in cytochrome P450 72A69. Plant Journal 89: 527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Ma Y, Zeng J, Duan L, Xue X, Wang H, Lin T, Liu Z, Zeng K, Zhong Y et al. 2016. Convergence and divergence of bitterness biosynthesis and regulation in Cucurbitaceae. Nature Plants 2: 16183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra for unacylated avenacins detected in roots of Avena strigosa avenacin-deficient mutants shown in Fig. 1(c). Fig. S2 GC-MS total ion chromatograms (TIC) from analysis of extracts of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves expressing AstHMGR and AsbAS1, or AstHMGR, AsbAS1 and AsCYP51H10 with candidate CYPs. Fig. S3 Electron-impact mass spectra for 12,13β-epoxy-16bhydroxy-β-amyrin (EpHβA) and putative 12,13β-epoxy-16,21βhydroxy-β-amyrin (EpdiHbA). Fig. S4 NMR assignment for 12,13β-epoxy,16β,21β-dihydroxyb-amyrin-3β-O-L-arabinose. Fig. S5 Electron-impact mass spectra for the product coeluting with 21-hydroxy-β-amyrin. Fig. S6 Identification of additional AsCYP72A475 (sad6) mutants by LC-MS metabolic profiling. Fig. S7 Schematic of AsCYP72A475 and mutation sites in sad6 mutants. Methods S1 Metabolite extraction, LC-MS-MS and LC-MSFluorescence analysis of oat roots. Methods S2 Metabolite extraction and LC-MS-CAD analysis of extracts of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Methods S3 Purification and structural elucidation of 12,13-epoxy,16,21-dihydroxy-β-amyrin-3-O-L-arabinose. Methods S4 Structural analysis of AsCYP72A475. Table S1 Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for Gateway cloning of coding sequences of the candidate CYP genes. Table S2 Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for sequencing of the genomic DNA region encoding for the Sad6 gene. Table S3 Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for RT-PCR expression profiling of the candidate CYPs from Avena strigosa. Table S4 Oligonucleotide primer sequences Primers used for quantitative PCR expression profiling of Avena strigosa CYPs.