Abstract

Polycomb repression is critical for metazoan development. Equally important but less studied is the Trithorax system, which safeguards Polycomb target genes from the repression in cells where they have to remain active. It was proposed that the Trithorax system acts via methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 and lysine 36 (H3K36), thereby inhibiting histone methyltransferase activity of the Polycomb complexes. Here we test this hypothesis by asking whether the Trithorax group protein Ash1 requires H3K36 methylation to counteract Polycomb repression. We show that Ash1 is the only Drosophila H3K36‐specific methyltransferase necessary to prevent excessive Polycomb repression of homeotic genes. Unexpectedly, our experiments reveal no correlation between the extent of H3K36 methylation and the resistance to Polycomb repression. Furthermore, we find that complete substitution of the zygotic histone H3 with a variant in which lysine 36 is replaced by arginine does not cause excessive repression of homeotic genes. Our results suggest that the model, where the Trithorax group proteins methylate histone H3 to inhibit the histone methyltransferase activity of the Polycomb complexes, needs revision.

Keywords: Ash1, Drosophila, H3K36 methylation, Polycomb, Trithorax

Subject Categories: Chromatin, Epigenetics, Genomics & Functional Genomics

Introduction

Polycomb repression is essential to maintain cell type specific gene expression programmes in a wide range of multicellular animals including Drosophila, mice and humans 1, 2, 3. It is potent and once established tends to repress target genes for many cell generations. Polycomb proteins, the building blocks of the repressive system, are ubiquitous but the set of genes they repress varies between different cell types. For example, homeotic selector (HOX) genes of the bithorax complex are repressed by Polycomb in the anterior half of the fly body but remain transcriptionally active in the posterior half 4, 5. The genetic evidence indicates that Trithorax (Trx) and Absent, small or homeotic discs 1 (Ash1) proteins are critical to safeguard Drosophila Polycomb target genes from erroneous repression in cells where they have to remain active 6, 7, 8. Importantly, neither Trx nor Ash1 are responsible for transcriptional activation of the Polycomb target genes, which is done by appropriate enhancers and associated transcription factors. Instead, the two, in some way, specifically antagonize Polycomb repression 9, 10.

Polycomb proteins act as multisubunit complexes that affect chromatin organization in multiple ways, which includes posttranslational modification of histone proteins 2, 11, 12. Of those, tri‐methylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3) by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) is essential for repression 13. In vitro experiments indicate that the catalytic activity of PRC2 is inhibited by prior methylation of histone H3 tail at lysine 4 (K4) and lysine 36 (K36) 14, 15, 16. Trx and Ash1 both have SET domains that can methylate H3K4 and H3K36, respectively 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. From this, it was proposed that Trx and Ash1 counteract Polycomb repression by inhibiting PRC2 catalytic activity via H3K4 and H3K36 methylation 14, 15, 16.

The model provides a simple mechanistic explanation of the antagonism between Trx/Ash1 and Polycomb repression. However, several observations do not easily fit to the model. First, there are other Drosophila histone methyltransferases, Set1 and Trr 21, 22, 23 that can methylate H3K4 and two histone methyltransferases NSD and Set2 24, 25 that can methylate H3K36. Why these are not redundant with Trx and Ash1 is unclear. Second, methylated H3K4 or H3K36 have to be present on the same H3 tail to inhibit PRC2 activity 15. Therefore, nucleosomes have to be extensively methylated by Trx and Ash1 to block Polycomb repression efficiently. However, recent quantitative mass spectrometry study indicates that in Drosophila cells only a very small fraction of histone H3 is methylated at K36 (H3K36me1 = 2.5% of total, H3K36me2 = 0.5% of total and H3K36me3 = 1.5% of total) 26. Since these modifications are widely spread over the Drosophila genome 27, their density at any given site is expected to be very low. Third, transgenic experiments of Hödl and Basler 28 indicate that flies in which all zygotic histone H3 molecules carry arginine or alanine instead of lysine 4 (K4) have no ectopic repression of HOX or other developmental genes. The latter cannot be ascribed to the redundancy with Ash1‐mediated H3K36 methylation as individual loss‐of‐function mutations in trx and ash1 both cause stochastic loss of HOX gene expression 6, 7, 8, 9. Finally, chromatin immunoprecipitation studies in Drosophila embryos and cultured cells indicate that, when Polycomb‐regulated genes are transcriptionally active, they often lose PRC2 binding 29, 30, 31. The loss of methyltransferase would automatically cause the loss of H3K27me3 leaving no need to invoke special mechanisms to inhibit catalytic activity of PRC2.

HOX genes specify anterior–posterior axis of multicellular animals. In Drosophila, the HOX genes are grouped in two clusters: the Antennapedia complex that encompasses genes responsible for the identity of the segments that form the head and the anterior thorax 32 and the bithorax complex, which groups genes that specify the third thoracic and all abdominal segments 4. Both clusters are classical targets of Polycomb/Trithorax regulation and changes in their gene expression patterns proved to be one of the best readouts to detect defects in the Polycomb or Trithorax functions 6, 33, 34, 35, 36. For example, in mutants lacking any of the core Polycomb proteins, the expression of the HOX genes is not confined to appropriate segments, which leads to transformations of multiple segments towards the more posterior neighbours 6, 33, 34, 35. On the other hand, impaired trx or ash1 function causes stochastic loss of HOX gene expression and partial transformation of corresponding segments towards the anterior fate 6, 36.

Here we investigated whether Ash1 counteracts Polycomb repression by methylating K36 on histone H3. Unlike the Trx protein, which binds Polycomb target genes both when they are repressed and when they are transcriptionally active 31, 37, Ash1 is a hallmark of the de‐repressed state 31, 38, 39. Using a combination of genetic and biochemical approaches, we, for the first time, showed that Ash1 is the only Drosophila H3K36‐specific methyltransferase required to prevent excessive Polycomb repression of the HOX genes. Surprisingly, our experiments demonstrated that complete substitution of the zygotic histone H3 with a variant in which lysine 36 is replaced by arginine does not lead to ectopic repression of homeotic genes. Altogether, our results suggest that the model, where the Trithorax group proteins methylate histone H3 to inhibit the histone methyltransferase activity of PRC2, may need to be reconsidered.

Results

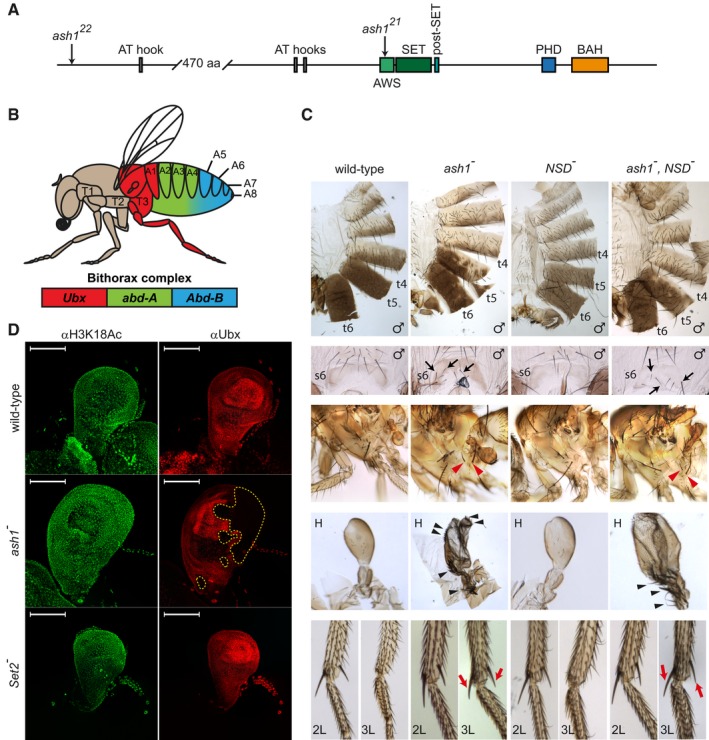

If Ash1 counteracts Polycomb repression by methylating H3K36, other H3K36‐specific histone methyltransferases may also contribute to the process. To address this question, we examined stochastic loss of the homeotic gene expression in flies with mutations in the ash1, NSD and Set2 genes. As previously reported 7, 8, 40, 41, flies with combinations of mutant ash1 alleles lose expression of the bithorax complex genes and display transformations of thoracic and abdominal segments. The ash1 22 allele is a point mutation that converts Gln 129 into a stop codon (Fig 1A, 8). The truncated open reading frame of ash1 22 encodes for a short non‐functional polypeptide that lacks all conserved domains. The ash1 21 allele is a substitution of Glu 1365 to Lys within the Associated With SET (AWS) domain (Fig 1A, 8). The ash1 22/ash1 21 heterozygotes develop to pharate adult stage and about 12% survive as adults. The mutant adult flies show haltere to wing and third leg towards second leg transformations, characteristic of partial loss of the Ubx gene expression (Fig 1B and C). In addition, they show transformations of the 5th and 6th abdominal segments towards more anterior fate (Fig 1B and C), which reflect partial loss of the Abd‐B gene expression. The ash1 Df(3L)Exel9011 allele (hereafter referred to ash1 9011) is a large deletion that removes the entire ash1 and several other genes 42. Nearly all ash1 22/ash1 9011 animals die at early pupal stage before the adult cuticle is formed. The single ash1 22/ash1 9011 male with the adult cuticle developed enough to examine its morphology showed clear posterior to anterior transformations of the third thoracic and abdominal segments.

Figure 1. Ash1 is the only H3K36‐specific methyltransferase critical to counteract Polycomb repression of the Drosophila HOX genes.

- The schematic of the Drosophila Ash1 protein organization. Ash1 is 2,226 amino acid long and contains eight domains (indicated by coloured rectangles). The SET domain together with the AWS (Associated With SET) and the post‐SET domains are necessary and sufficient for Ash1 histone methyltransferase (HMTase) activity. The functions of the BAH (Bromo Adjacent Homology), PHD (Plant homeodomain) and AT‐hook domains are unknown. The positions of ash1 22 and ash1 21 point mutations are indicated by arrows.

- Segmental expression of the Drosophila bithorax complex genes. The three genes of the complex, Ubx, abd‐A and Abd‐B, are shown as coloured rectangles. The expression of Ubx gives identity to the third thoracic (T3) and the first abdominal (A1) segments, the expression of abd‐A defines the second, third and fourth abdominal segments (A2–A4), and the expression of Abd‐B gives identity to the rest of the abdominal segments (illustrated with corresponding colour code).

- Adult phenotypes of the ash1 and NSD mutants. In ash1 22/ash1 21 mutants (designated as ash1 −), the loss of Abd‐B expression results in partial transformation of abdominal segments 6 and 5 towards segments 5 and 4, which is visible from the partial loss of pigmentation on tergites 5 and 6 (t5 and t6) and appearance of bristles on sternite 6 (s6, marked with black arrows). The loss of Ubx expression causes transformation of the third thoracic to the second thoracic segment visible as partial haltere (H) to wing and third leg (3L) to second leg (2L) transformations. The former is evident from the change in the haltere shape and the appearance of multiple bristles (black arrowheads). The latter is indicated by the apical and pre‐apical bristles (red arrows) on the tibia of the third leg of ash1 mutants. These are normally present on 2L but absent on 3L (compare to wild‐type). Also note the appearance of additional hypopleural bristles on the third thoracic segment of the ash1 − flies (red arrowheads), which indicate its transformation towards the second thoracic segment. Phenotype of the NSD ds46/NSD ds46 (NSD −) flies is indistinguishable from wild‐type and the phenotype of the double ash1 22 ,NSD ds46/ash1 22 ,NSD ds46 (ash1 − ,NSD −) flies is no more severe than that of the single ash1 22/ash1 21 (ash1 −) mutants.

- Ubx expression in the haltere imaginal discs. The expression was assayed by immunostaining with antibodies against Ubx (red) and acetylated H3K18 (green, positive control). While ash1 22/ash1 21 (ash1 −) larvae show stochastic clonal loss of the Ubx immunostaining in haltere discs (yellow dashed lines), Set2 − larvae have uniform expression of Ubx throughout the haltere disc, resembling that in the wild‐type larvae. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

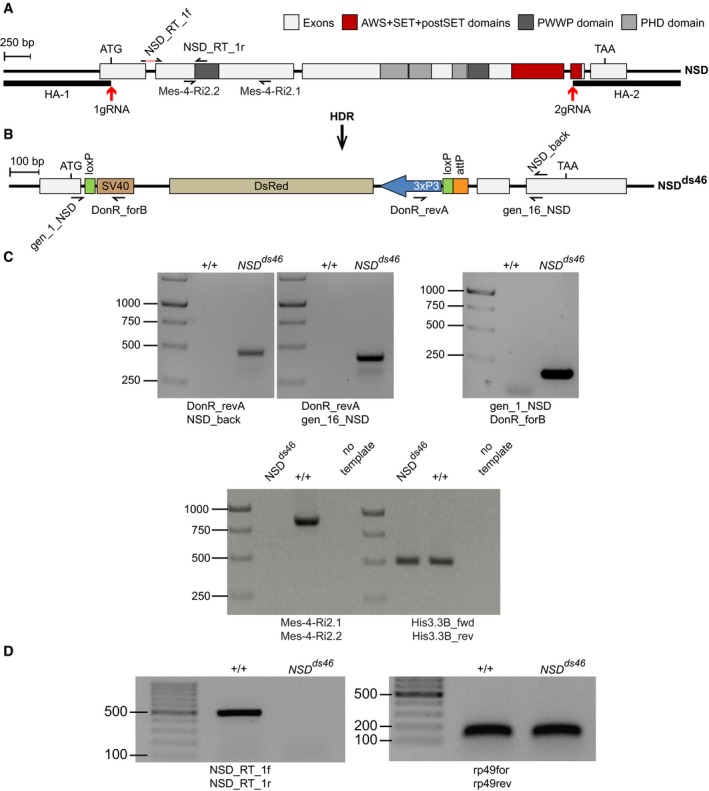

No loss‐of‐function alleles for the NSD gene have been described to date. Therefore, we used CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated mutagenesis 43 to replace the entire NSD open reading frame with a DsRed transgene driven by a synthetic eye‐specific 3xP3 promoter (Fig EV1). Flies homozygous for resulted NSD ds46 allele are viable, fertile and show no homeotic transformations (Fig 1C). Both Ash1 and NSD were said to di‐methylate H3K36 24, 44. Nevertheless, the NSD ds46 allele does not reduce the viability or enhance the homeotic transformations of ash1 mutants (Fig 1C). These observations indicate that NSD is not required to counteract Polycomb repression of the homeotic genes.

Figure EV1. Generation of the NSD loss‐of‐function allele.

- The structure of the Drosophila NSD locus. Red arrows indicate locations of the gRNA sites used for CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated replacement of the NSD Open Reading Frame (ORF) with DsRed. The homology regions HA‐1 and HA‐2, used for the replacement, are shown with bold lines. The half‐arrows represent the primers used for genotyping of the mutant allele. The dashed red line in NSD_RT_1f primer, used for RT–qPCR, indicates the intronic region that is excluded from the primer.

- The NSD ds46 allele. After Homology‐directed Repair (HDR), the insertion of the DsRed cassette generates the loss‐of‐function allele NSD ds46, where DsRed substitutes most of the NSD ORF. The DsRed expression is controlled by the 3xP3 promoter. In addition to DsRed, the replacement cassette contains two loxP sites to remove DsRed via Cre‐mediated recombination and an attP docking site to insert variants of the NSD ORF. The half‐arrows represent the primers used to genotype the mutant allele.

- Genotyping of the NSD ds46 allele by PCR. The replacement of the NSD ORF by the DsRed cassette was confirmed by PCR with four different primers pairs. Three primer pairs (top row of images) yield the product only if the replacement has happened. The expected sizes of the PCR products are 469, 427 and 186 bp for DonR_revA and NSD_back, DonR_revA and gen_16_NSD, and gene_1_NSD and DonR_forB primer pairs, respectively. The PCR with Mes‐4‐RI‐2.1 and Mes‐4‐RI‐2.2 primer pair amplifies the 830 bp product only from the wild‐type allele. PCR with His3.3B_fwd and His3.3B_rev primer pair, amplifying the 495 bp DNA fragment from the His3.3B gene, was used as a positive control.

- The NSD ds46 allele produces no messenger RNA. This was confirmed by RT–PCR with NSD_Rt_1f and NSD_Rt_1r primer pair, which yields the 513 bp product only when the intact NSD mRNA is produced. RT–PCR with rp49for and rp49rev primer pair that amplifies 132 bp fragment from the cDNA of constitutively expressed RpL32 (a.k.a rp49) gene was used as positive control.

The reported mutation of the Drosophila Set2 gene (Set2 1) removes the N‐terminal half of its open reading frame, which includes the catalytic SET domain 25. Most of the Set2 1 homozygous flies die during metamorphosis. The lethality can be complemented by a transgenic copy of the Set2 genomic region, which indicates that the mutant chromosome does not contain second site lethal mutations 25. In our hands, from 300 Set2 1 homozygous larvae picked at the first instar and grown separately from their heterozygous siblings, 221 formed pupal cases but only five males and three females formed some chitin structures, including one male with fully developed adult cuticle (Appendix Fig S1). None of the cuticle structures showed signs of homeotic transformations suggesting that the Set2 protein is not essential to counteract Polycomb repression of the HOX genes. To test this further, we compared the haltere imaginal discs from the wild‐type, ash1 22/ash1 21 and Set2 1 third instar larvae stained with antibodies against the Ubx protein. Consistent with previous reports, the ash1 22/ash1 21 discs showed clonal patches of cells lacking Ubx immunostaining 9, 40. In contrast, the discs from the wild‐type and the Set2 1 larvae displayed uniform Ubx staining (Fig 1D), supporting the conclusion that Set2 is not required to counteract Polycomb repression of the HOX genes.

To summarize, our observations suggest that, from the three Drosophila H3K36‐specific histone methyltransferases, only Ash1 is critical to prevent the unscheduled Polycomb repression of the homeotic genes.

Ash1 SET domain is required to counteract Polycomb repression

If Ash1 is the only H3K36‐specific methyltransferase critical to counteract Polycomb repression, something in its mode of action must differ from that of NSD and Set2. Ash1 may be specifically targeted to Polycomb‐regulated genes, it may methylate some non‐histone substrates, or it could have functions unrelated to methyltransferase activity.

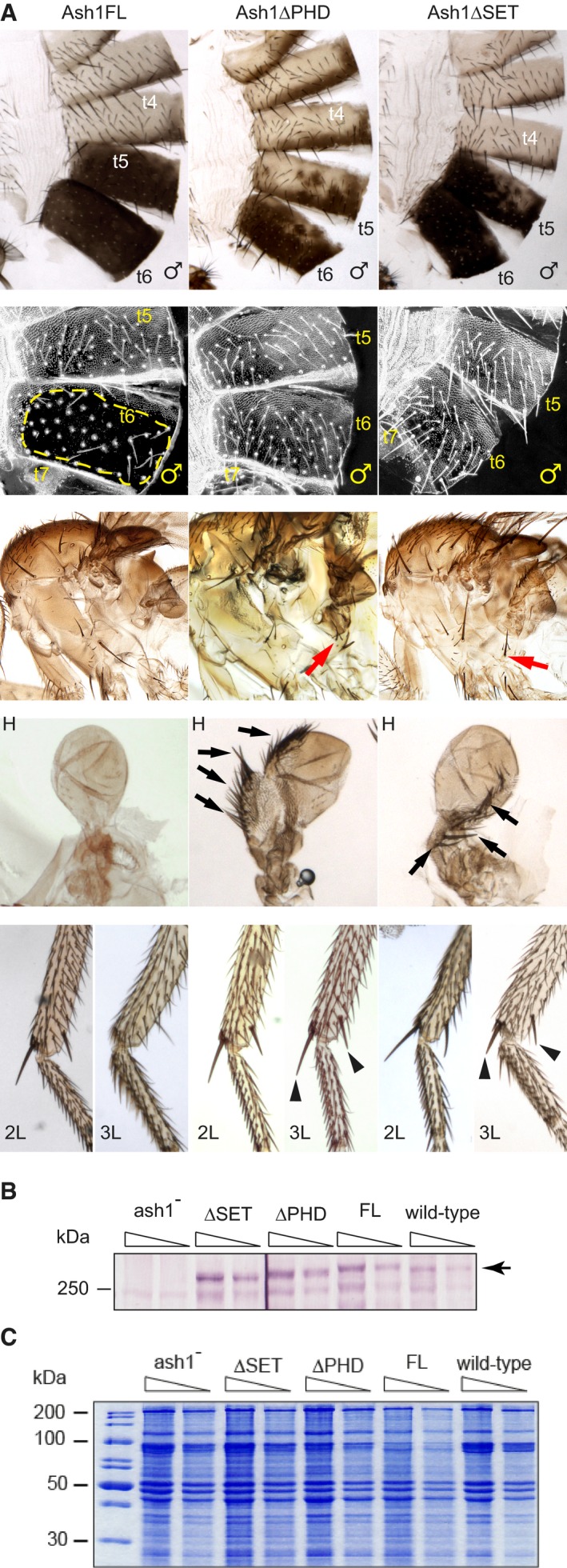

The latter option seems unlikely considering recent reports that Ash1 interacts with Mrg15 and that this interaction enhances the catalytic activity of Ash1 and helps to antagonize Polycomb repression 40, 41. To investigate this option further, we generated transgenic fly strain that expressed the full‐length Ash1 (Ash1‐FL) protein as well as strains that expressed the Ash1 variants lacking either the SET domain (Ash1∆SET) or the PHD domain (Ash1∆PHD), all under control of the Ubi‐p63E promoter 45. The flies carrying either of the transgenic constructs along with a copy of the endogenous wild‐type ash1 are fully viable, fertile and display no homeotic transformations. This indicates that the deletion of the SET or PHD domains, or potential overexpression of the transgenic Ash1 proteins, does not have adverse dominant effects. When introduced into the ash1 22/ash1 9011 background, one or two copies of the transgene expressing full‐length Ash1 restore the viability and yield flies with no homeotic transformations (Fig 2A, Appendix Fig S2). Somewhat surprisingly, the ash1 22/ash1 9011 strain supplemented with two copies of the ash1∆SET or the ash1∆PHD transgene also yields viable adult flies (Appendix Fig S2). These flies, however, have low fitness and no stable stocks could be established. Importantly, all ash1 22/ash1 9011 flies expressing the Ash1∆SET or Ash1∆PHD proteins show homeotic transformations indicating that the expression of HOX genes is still stochastically lost (Fig 2A). Since transgenic Ash1‐FL, Ash1∆SET or Ash1∆PHD are expressed at comparable levels (Fig 2B and C), this argues that the SET and the PHD domains of Ash1 are required to counteract Polycomb repression of the HOX genes.

Figure 2. Ash1 SET domain is required to counteract Polycomb repression.

- Adult phenotypes of the ash1 22/ash1 9011 flies supplemented with transgenic constructs expressing either the full‐length Ash1 (Ash1FL) or the truncated variants lacking the PHD (Ash1ΔPHD) or the SET (Ash1ΔSET) domains. Note extra hypopleural bristles (red arrows), the third leg (L3) to second leg (L2), haltere (H) to wing, t5–t4 and t6–t5 transformations in the Ash1ΔPHD and the Ash1ΔSET but not in the Ash1FL flies. The latter are evident from the partial loss of pigmentation in t6 and t5, or the appearance of small bristles (trichomas) on t6 of the Ash1ΔPHD and the Ash1∆SET flies in the area that is normally naked (Ash1FL, yellow dashed line). The transformed L3 acquire apical and pre‐apical bristles on the tibia (black triangles) while halteres change shape and acquire rows of bristles (black arrows).

- Twofold dilutions of total nuclear protein extracts from the third instar larvae of the ash1 22/ash1 9011 mutants supplemented with various transgenic constructs and wild‐type flies were analysed by Western blot with anti‐Ash1 antibodies. Arrow indicates the position of Ash1 protein. Note that transgenic proteins are expressed at comparable level.

- Coomassie staining of SDS–PAGE separated protein extracts from (B) was used to control the loading.

Source data are available online for this figure.

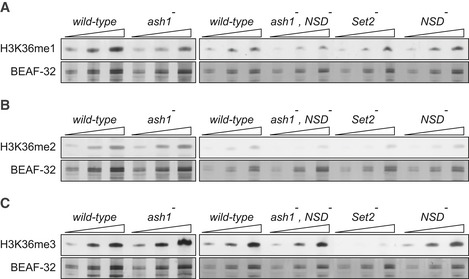

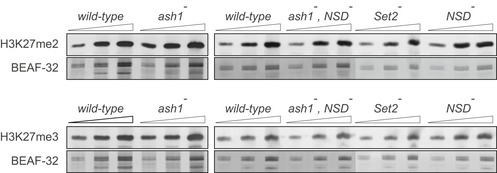

Western blot analyses showed no major difference in the overall levels of H3K36me1, H3K36me2 and H3K36me3 between the wild‐type and ash1 22/ash1 9011 third instar larvae (Fig 3A and C). However, we noted mild (~ 2‐fold) reduction of H3K36me1, also visible in the ash1 22/ash1 9011, NSD ds46 double mutants but not in the Set2 1 mutants (Fig 3A). Consistent with previous reports, the Set2 1 mutant larvae displayed tenfold reduction in H3K36me3 25 as well as slight loss of H3K36me2 (Fig 3B and C). Neither mutant showed increase in the level of bulk di‐ or tri‐methylated H3K27 (Fig EV2). Altogether, these results suggest that Ash1 is not solely responsible for any of the H3K36 methylation states and that aside from H3K36me3, which is produced predominantly by Set2, all three methylases contribute to the H3K36me1 and H3K36me2 pools.

Figure 3. Western blot analysis of the bulk H3K36 methylation in larval tissues of various mutants.

-

A–CTwofold serial dilutions of the total protein extracts from the wild‐type, ash1 22/ash1 9011 (ash1 −), ash1 22 ,NSD ds46/ash1 9011 ,NSD ds46 (ash1 − , NSD −) and Set2 1 (Set2 −) larval brains, imaginal discs and salivary glands were analysed by Western blot with antibodies against H3K36me1 (A), H3K36me2 (B) and H3K36me3 (C). Note the strong (> 10‐fold) reduction of H3K36me3 signal in the Set2 − extract and the slight (˜ 2‐fold) reduction of H3K36me1 signal in the ash1 − and ash1 − , NSD − extracts. The protein extracts from the wild‐type, double ash1 − , NSD − and single NSD − and Set2 − mutants (right panels) were analysed together on the same membrane; however, the images of the H3K36me1 and H3K36me3 Western blots were modified to splice out the marker lane between the ash1 − , NSD − and the Set2 − extracts. Western blots with constitutively expressed BEAF‐32 protein were used as loading controls.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV2. H3K27 methylation in the Drosophila larvae lacking different H3K36‐specific histone methyltransferases.

Western blot analysis of the ash1 − (ash1 22/ash1 9011), ash1 − ,NSD − (ash1 22 ,NSD ds46/ash1 9011 ,NSD ds46), Set2 − (Set2 1/ Set2 1) and NSD − (NSD ds46/NSD ds46) mutants shows no change in global levels of di‐ and tri‐methyl H3K27 compared to wild‐type (Oregon R). Twofold serial dilutions of total protein extracts from larval brains, imaginal discs and salivary glands were analysed by Western blot with corresponding antibodies. The protein extracts from the wild‐type, double ash1 − , NSD − and single NSD − and Set2 − mutants (right panels) were analysed together on the same membrane; however, the images were modified to splice out the marker lane between the ash1 − , NSD − and the Set2 − extracts. Western blots with constitutively expressed BEAF‐32 protein were used as loading controls.Source data are available online for this figure.

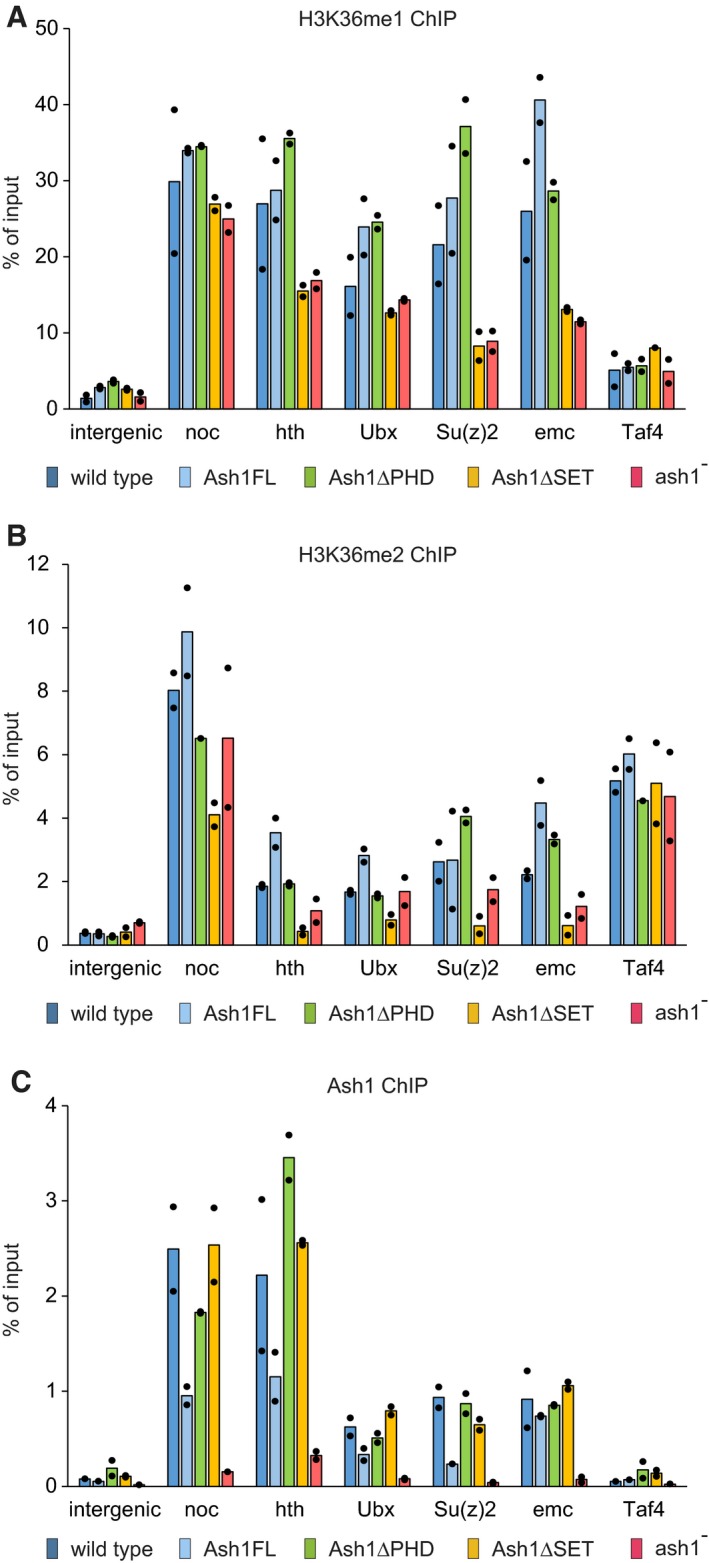

Although its contribution to the bulk H3K36 methylation is limited, Ash1 may be critical for the appropriate level of H3K36 methylation at de‐repressed Polycomb target genes. To address this question, we assayed the presence of Ash1, H3K36me1 and H3K36me2 at five genomic sites using Chromatin Immunoprecipitation coupled with quantitative PCR (ChIP‐qPCR). Studies in cultured Drosophila cells suggested two modes of Ash1 binding to the genome. The first mode produces numerous weak binding sites biased towards long 5′ introns of transcriptionally active genes 38, 41. The second mode results in few dozens of strongly bound regions many of which represent Polycomb‐regulated genes captured in transcriptionally active state 31, 38, 41. Here we selected three developmental genes no ocelli (noc), homothorax (hth) and extra macrochaetae (emc), which displayed the strong Ash1 binding in multiple cultured cell lines 31, 38. One of the genes, hth, was previously shown to bind Polycomb proteins when transcriptionally inactive 31. We also included the two well‐known Polycomb target genes Su(z)2 and Ubx. Both were shown to bind Ash1 when transcriptionally active 31, 39 and Ubx is one of the genes whose erroneous repression causes some of the homeotic transformations seen in the ash1 mutants. Finally, we assayed an intergenic region on chromosome 3R and the constitutively active TBP‐associated factor 4 (Taf4) gene. Neither of them is known to bind Ash1 31, 38 and, therefore, can serve as negative controls.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and quantitative PCR analysis (ChIP‐qPCR) indicates that, following the Ash1 depletion in the ash1 22/ash1 9011 third instar larvae, H3K36me1 is mildly (~ 2‐fold) reduced at some of the selected genes (Figs 4A and EV3), while the H3K36me2 levels are not measurably affected (Fig 4B). The detected reduction of H3K36me1 is small. Nevertheless, the partial loss of H3K36me1 is completely reversed by the re‐introduction of the transgenes expressing the wild‐type and the PHD‐deficient but not the SET domain‐deficient Ash1 proteins (Fig 4A). This suggests that the partial loss of H3K36me1 from the Ash1‐bound genes is caused by the loss of Ash1 catalytic activity. Importantly, while the Ash1∆SET and Ash1∆PHD proteins are expressed (Fig 2B) and bind the chromatin with comparable efficiency (Fig 4C) and the Ash1∆PHD protein restores the wild‐type levels of H3K36me1 (Fig 4A), the transgenic ash1∆PHD, ash1 22/ash1 9011 flies still have homeotic transformations (Fig 2A). Altogether, our observations indicate that Ash1 mono‐methylates a measurable fraction of the nuclear H3K36 and that Ash1 SET domain is required to counteract Polycomb repression of the HOX genes. Yet, there seems to be no correlation between the levels of methylated H3K36 (bulk or at specific loci) and the extent of the erroneous Polycomb repression.

Figure 4. ChIP and quantitative PCR (ChIP‐qPCR) analysis of H3K36 methylation and Ash1 binding.

-

A–CChromatin from the wild‐type (dark blue bars), ash1 22/ash1 9011 (ash1−, red bars) and transgenic ash1 22/ash1 9011 (Ash1FL, light blue bars; Ash1ΔPHD, green bars; Ash1ΔSET, orange bars) larvae was subjected to immunoprecipitation with the antibodies against H3K36me1 (A), H3K36me2 (B) and Ash1 (C). Histograms show the mean of the two independent experiments (n = 2) with dots indicating individual experimental results. An intergenic region on chromosome 3R (intergenic) and the constitutively active TBP‐associated factor 4 (Taf4) gene serve as controls. The loss of Ash1 ChIP signal in the ash1 − larvae indicates that the selected genes are the genuine Ash1 binding sites.

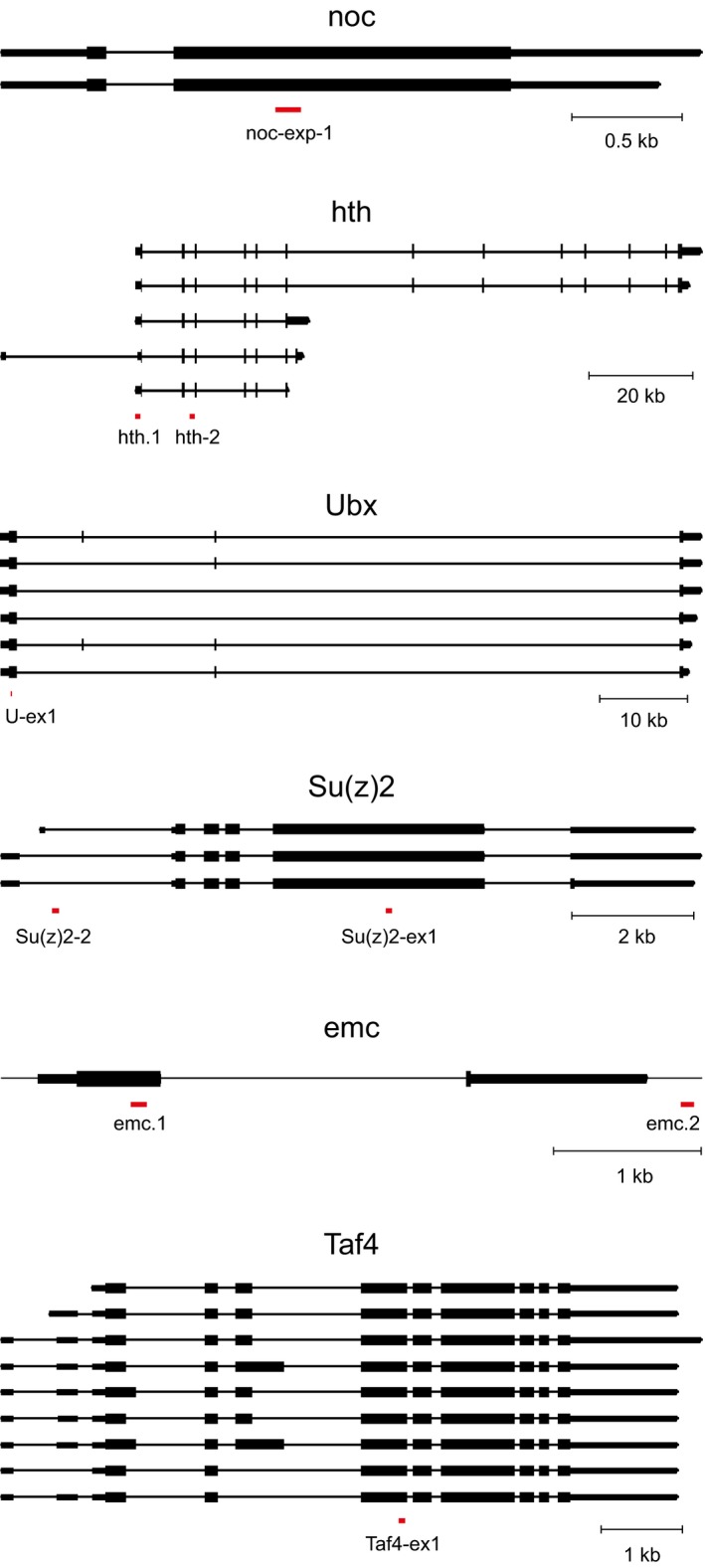

Figure EV3. Schematic of target genes selected for ChIP‐qPCR analyses.

Gene exons are shown as thick boxes for coding parts and thin boxes for 5′‐ and 3′‐UTRs, the introns are indicated with strait lines. All isoforms are listed. The schematics are drawn to scales indicated with scale bars below each gene. The positions of PCR amplicons used for the analyses are marked with red boxes.

Loss of zygotic H3K36 methylation does not affect the expression of HOX genes

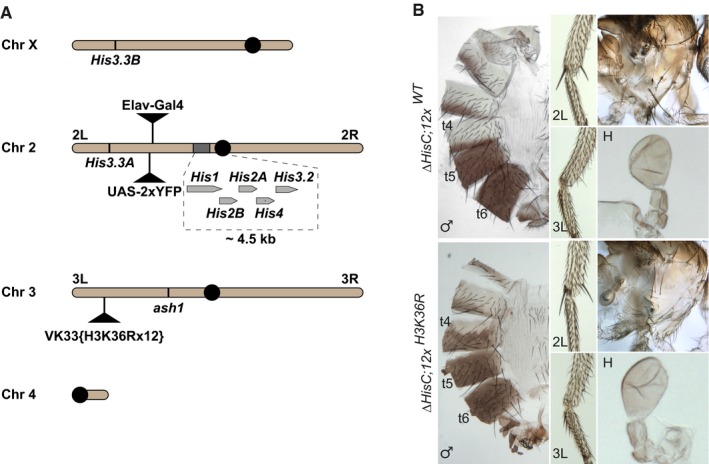

The unexpected lack of clear anti‐correlation between the amount of methylated H3K36 and the extent of the erroneous Polycomb repression made us wonder whether H3K36 methylation is required to counteract the repression. To address this issue, we turned to the transgenic flies that combine the deletion of the histone gene cluster Df(2L)HisC ED1429 (hereafter ΔHisC) 46 with the BAC‐based transgenic construct carrying twelve copies of the 5 kb histone repeat unit in which H3K36 is mutated to arginine (12x H3K36R) (Fig 5A, 47). The transgene carrying wild‐type histone repeats (12x WT) inserted in the same genomic location was used as a control. The 12x WT transgene fully complements the ΔHisC deletion yielding viable, fertile and morphologically normal flies 47. In contrast, the combination of the homozygous ΔHisC deletion with one copy of the 12x H3K36R transgene is lethal 47. In our hands, when separated from their heterozygous siblings at the first instar larval stage, the ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R animals survive till pharate adult stage with some adults escaping from the pupal case to die shortly after (Fig EV4). Strikingly, the ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R flies display no homeotic transformations (Fig 5B), indicating that zygotic replacement of the histone cluster with the 12x H3K36R transgene does not cause erroneous repression of the HOX genes. The simplest explanation of this finding is that H3K36 methylation is not required to maintain the HOX gene expression. However, more complex alternative explanations are possible. First, the H3K36 methylation by Ash1 may be needed to prevent the erroneous repression by the Polycomb proteins, not as the modification that inhibits the histone methyltransferase activity of PRC2 but as a placeholder, which prevents some other modification of this lysine 36. Replacing this lysine with arginine would automatically prevent such modification and thereby bypass the need for the Ash1‐mediated H3K36 methylation. Second, in addition to the HisC gene cluster, which contains twenty‐three gene copies encoding the H3.2 histone variant, Drosophila has two distinct loci, one on the first and one on the second chromosomes, which encode the variant H3.3 histones (Fig 5A). In the ΔHisC flies, both H3.3 genes remain intact. Conceivably, the Ash1‐mediated methylation of H3.3 is sufficient to counteract Polycomb repression.

Figure 5. Zygotic replacement of replication coupled H3.2K36 with H3.2R36 does not cause ectopic repression of HOX genes.

- Chromosomal positions of various histone H3 genes, ash1 and marker transgenes. Twenty‐three histone gene repeat units, each containing single His1, His2B, His2A, His4 and His3.2 gene, are clustered near the centromere (black circle) of chromosome 2. These histone genes are removed by the ΔHisC deletion. To select the animals homozygous for the deletion, the ΔHisC chromosomes are marked with insertions of either Elav‐Gal4 or UAS‐2xYFP transgenes (black triangles on chromosome 2L). The His3.3A and His3.3B genes encode the same protein, but reside on chromosomes 2L and X. The transgenes carrying twelve copies of either the wild‐type histone repeat unit (12x WT) or the unit in which H3 gene is altered to have K36 replaced with arginine (12x H3K36R) are inserted in the same attP site (black triangle on chromosome 3L) 47. The ash1 gene is located on the same chromosome arm.

- The ΔHisC; 12x H3K36R and control ΔHisC; 12x WT flies show no homeotic transformations and are indistinguishable from the wild type.

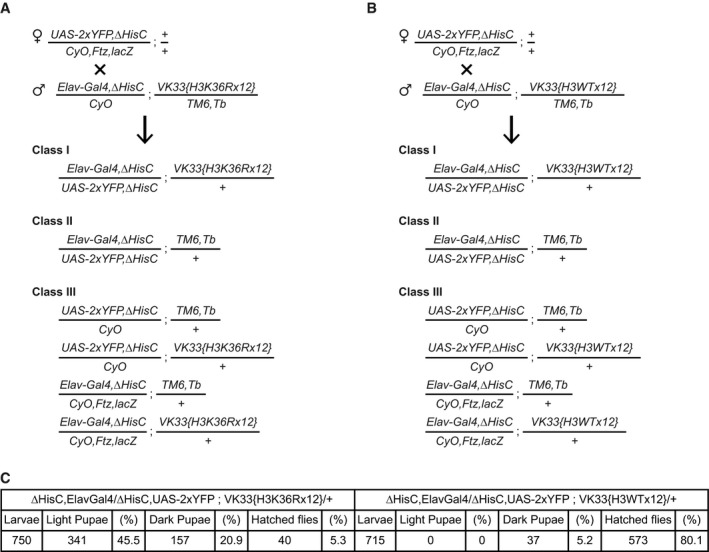

Figure EV4. Generation of flies with zygotic H3.2K36 replaced by H3.2R36.

-

A, BTo generate the desired flies, females carrying ΔHisC recombined with the UAS‐2xYFP transgene were crossed to males carrying ΔHisC recombined with the Elav‐Gal4 transgene and one of the two variants of the transgene with 12 copies of the histone gene cluster. In one of the transgenes, all copies of His3.2 gene contained H3K36R mutation (A) and in the other, all copies of His3.2 were wild‐type (B). The crossing scheme and the progeny classes in (A) and (B) were identical. The Class I larvae were separated from the larvae of the other classes, based on the YFP signal. Although the Class II animals also show YFP signal, they die at early embryonic stages after running out of maternally deposited histones. The Class III larvae lack YFP signal and are easily distinguishable from Class I.

-

CTwelve transgenic copies of the wild‐type histone gene cluster complement the loss of endogenous HisC locus nearly completely (80.1%). However, the transgene carrying H3K36R mutation fails to compensate for the deletion of the endogenous histones cluster. Although a large fraction of these animals reaches the pupal stage (about 66%), only 5% of them reach the adult stage.

If the Ash1‐mediated H3K36 methylation is a placeholder and the K36R replacement bypasses the need to have it, we expect the 12x H3K36R transgene combined with the ΔHisC deletion to suppress some of the adverse effects of the Ash1 loss. For example, such flies would live longer than the ash1 22/ash1 9011 mutants, till pharate adult stage as the ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R flies do. To test this, we recombined the ash1 22 allele with the 12x H3K36R transgenic insertion and introduced the ΔHisC and the ash1 9011 chromosomes (Fig 5A, also see Appendix Figs S3–S5 for details). As illustrated by Appendix Fig S4, the ΔHisC; ash1 22, 12x H3K36R/ash1 9011 flies die at early pupal stage, exactly as the single ash1 22/ash1 9011 mutants, lending no support for the placeholder hypothesis.

The H3.2 histone is produced only during the S phase when it is used to package newly replicated DNA 48. In most cells, H3.2 comprises the bulk of the nuclear histone H3. The variant histone H3.3 is synthesized in smaller quantities but in a replication independent manner. Because of its availability outside the S phase, H3.3 gets incorporated at places where nucleosomes are lost throughout the cell cycle, often within the chromatin of actively transcribed genes, which have higher nucleosome turnover 49, 50. Flies deficient for both H3.3B and H3.3A genes are viable and show no homeotic transformations 51, 52. The latter indicates that H3.3 is not essential to counteract Polycomb repression of the HOX genes and, if H3K36 methylation is important for the process, Ash1 must be able to use H3.2 as a substrate.

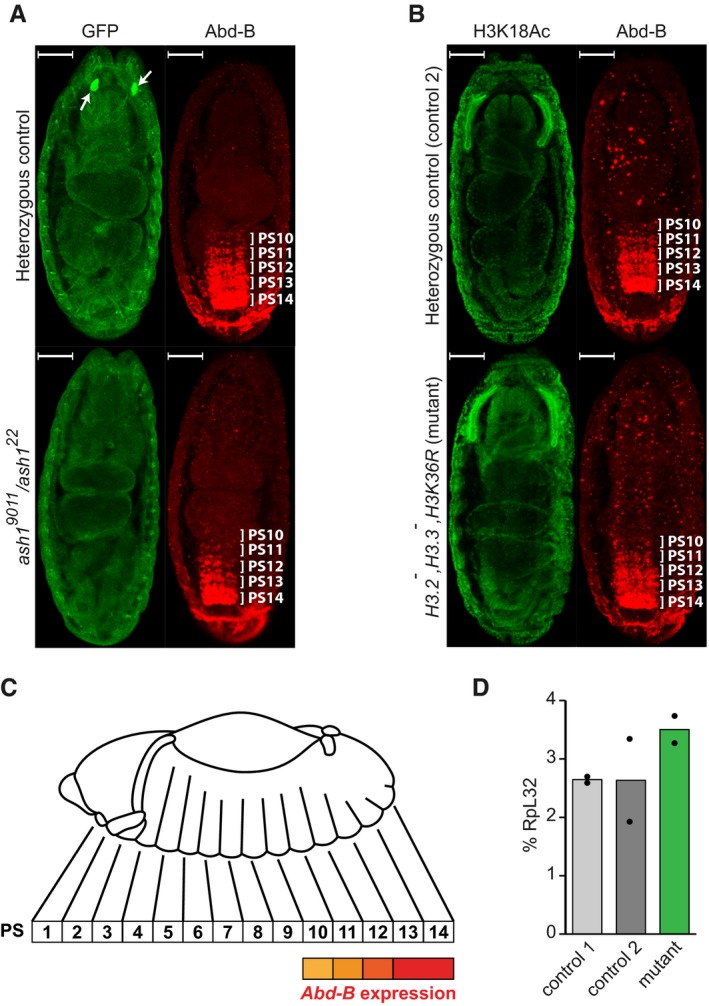

To test whether the presence of the wild‐type H3.3 can explain the lack of homeotic transformations in the ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R flies, we generated animals that combined deletions of both H3.3 genes, the ΔHisC deletion and the 12x H3K36R transgene (hereafter ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R (Figs 5A and EV5 and Appendix Figs S6–S10 for detailed description of the crosses). The ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R animals die at the first instar larval stage, which precludes examination of adult cuticles or larval imaginal discs. When we looked at larval denticle bands, which have shapes specific for each abdominal segment, we could see no signs of posterior to anterior homeotic transformations 6. At embryonic stages, the misexpression of the HOX genes is most easily detectable in cells of the segmented embryonic Central Nervous System (CNS). The loss of Abd‐B expression from CNS parasegments 10–12 of the ash1 22 homozygous embryos derived from ash1 22 mutant germ line cells was reported previously 9. It is also readily visible in the ash1 22/ash1 9011 embryos produced by heterozygous mothers (Fig 6A). However, when we immunostained the ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R embryos, we saw no differences in the Abd‐B expression compared to the control embryos heterozygous for ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC chromosome (Fig 6B and C). Consistently, RT–qPCR measurements of the Abd‐B mRNA level in the whole ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R stage 16 embryos showed no difference compared to the heterozygous control or the wild‐type strain (Fig 6D). Altogether, it appears that the replacement of all zygotic H3 with H3K36R does not cause the erroneous repression of the HOX genes.

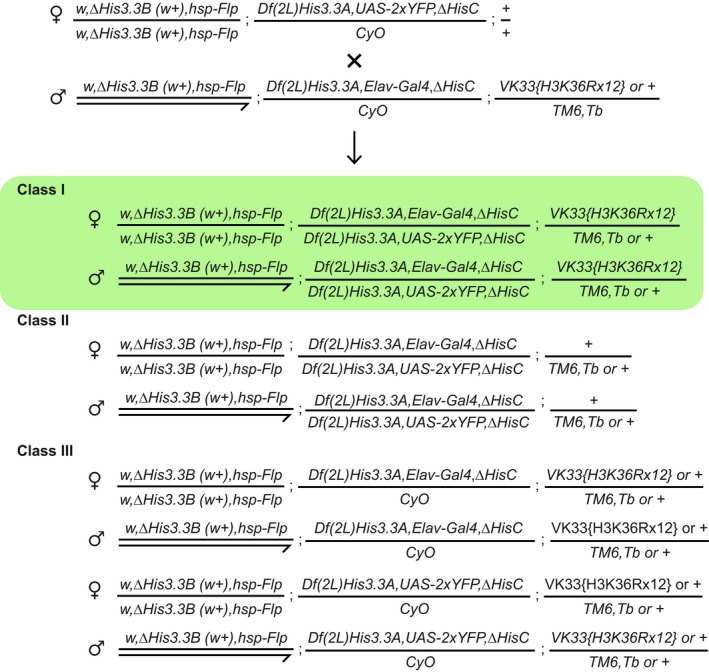

Figure EV5. Zygotic replacement of the wild‐type H3.2 and H3.3 histones with H3R36.

To generate the embryos where all zygotic H3 is replaced with H3R36, the w,ΔH3.3B(w + ),hsp‐Flp; Df(2L)His3.3A,UAS‐2xYFP,ΔHisC/CyO; +/+ females (from the stock generated as described in Appendix Fig S6) were crossed to the w,ΔH3.3B(w + ),hsp‐Flp; Df(2L)His3.3A,ElavGal4,ΔHisC/CyO; VK33{H3K36Rx12} or +/TM6,Tb males (generated as described in Appendix Fig S7). In the progeny, all embryos are homozygous for ΔHis3.3B deletion. The YFP‐positive embryos are also homozygous for both ΔHis3.3A and ΔHisC (deletion of histone cluster). From those, the Class II embryos die as they enter the S phase of cycle 15 when the pool of maternally loaded histones is depleted. However, the embryos supplemented with 12 copies of the histone repeat unit from the H3K36Rx12 transgene (Class I, highlighted in green) survive until the first instar larval stage. In these embryos, all zygotic histone H3 has Lys 36 substituted to Arg. Late embryos of this class were collected, genotyped by PCR as described in Appendix Fig S8 to verify their identity and examined for the Abd‐B expression. The remaining embryos (Class III) show no YFP signal since they do not combine the Elav‐Gal4 driver and UAS‐2xYFP reporter.

Figure 6. Zygotic replacement of H3.3K36 and H3.2K36 with H3.2R36 does not cause ectopic repression of Abd‐B in the central nervous systems.

- The Abd‐B expression in the Central Nervous System (CNS) of stage 16 embryos was assayed by immunostaining with antibodies against Abd‐B (red). In the ash1 22/TM3, Sb, e Kr::GFP or ash1 9011/TM3, Sb, e Kr::GFP embryos (heterozygous control), Abd‐B is expressed in parasegments 14–10 in a gradient that recedes from the posterior to anterior parasegment. In the ash1 22/ash1 9011 mutants, the Abd‐B gradient is much steeper, with reduced staining of parasegments 13 and 12 and at the edge of the detection in parasegments 11–10. Heterozygous control and ash1 22/ash1 9011 mutant embryos were stained together and separated by strong GFP expression (green) in the Bolwig's organs (white arrows). Here and in (B) the embryos are oriented with anterior pole facing the top and scaling bars correspond to 50 μm.

- Unlike ash1 mutants, embryos homozygous for His3.3A, His3.3B, ΔHisC deletions and supplemented with 12x H3K36R transgene (His3.2 − ,His3.3 − ,H3K36R) display the wild‐type Abd‐B immunostaining pattern (red), the same as the control embryos heterozygous for His3.3A, and ΔHisC deletions. In this experiment, immunostaining with antibodies against acetylated H3K18 (green) served as positive control.

- The schematic of the Abd‐B expression in the Drosophila embryo. Although homeotic transformations are often described according to the adult segments affected, the expression of the bithorax complex genes is regulated at the level of embryonic parasegments (PS), which are directly related to adult segments but slightly shifted relative to one another 5, 64.

- Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR (RT–qPCR) measurement of Abd‐B expression in His3.2 − ,His3.3 − ,H3K36R embryos. Expression of Abd‐B in stage 16 embryos, which are homozygous for His3.3A, His3.3B and ∆HisC deletions and carry 12x H3K36R transgene (mutant), is not reduced compared to their wild‐type counterparts (control 1) or embryos heterozygous for His3.3A, and ΔHisC deletions (control 2). Histograms show the mean of the two independent experiments (n = 2) with dots indicating individual experimental results.

Discussion

Three main conclusions could be drawn from the results presented here. First, the examination of homeotic gene expression in ash1, NSD and Set2 mutants suggests that Ash1 is the only Drosophila H3K36‐specific histone methyltransferase critical to counteract Polycomb repression. Second, the transgenic experiments with truncated Ash1 variants indicate that while the SET domain of Ash1, and likely its catalytic activity, are essential for the anti‐Polycomb function, the levels of methylated H3K36 (bulk and at specific loci) are not correlated with the ability to antagonize Polycomb repression. Third, the H3K36R replacement experiments show that the zygotic loss of methylatable H3K36 does not phenocopy the loss of ash1 function. Below we shall discuss one potential caveat of the latter experiments. Although the ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R embryos lack zygotic synthesis of the wild‐type H3, they derive from heterozygous females, which supply histone proteins and mRNAs to the embryo 53. Drosophila development starts with 13 rapid mitotic divisions where nuclei divide within single cytoplasm without cytokinesis. Two hours after fertilization, the first extended interphase (interphase 14) occurs, the zygotic genes start to be transcribed and cell membranes form around embryonic nuclei. Homozygous ΔHisC embryos complete the first 14 cell divisions but cannot progress past the S phase of 15th cycle since maternal histones and their mRNA get degraded during the G2 phase of cycle 14 46, 54. As development continues, most cells of the ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R embryos undergo two more rounds of cell division but the CNS cells, where we assayed the Abd‐B expression, divide five times 55. During each cell division, the pool of maternal histones within chromatin is diluted twofold. Hence, by stage 16 (13–16 h after fertilization) most cells of the embryo have their pools of maternal histones diluted fourfold (22) and, in the CNS, diluted 32‐fold (25). Assuming random incorporation of zygotic and maternal histones in the nucleosome, in the CNS cells of the ΔH3.3B, ΔH3.3A, ΔHisC, 12x H3K36R embryos, only 1 in 32 nucleosomes will have an H3 tail that can be methylated at lysine 36 and only 1 in 1,024 nucleosomes will have both tails that can be methylated at this position. If an H3 tail methylated at K36 can no longer be methylated at K27, could a single nucleosome with one “K27‐unmethylatable” H3 tail placed randomly within 6 kb long stretch of the fully “K27‐methylatable” chromatin prevent Polycomb repression? Although we cannot formally exclude this, it seems highly unlikely. For example, after the DNA replication, every second H3 molecule within H3K27me3 domains of Polycomb‐repressed genes becomes un‐methylated and it takes hours until the H3K27me3 density is fully restored 56. Yet, Polycomb repression endures as cells continue to proliferate.

To summarize, our experiments argue that Ash1 counteracts Polycomb repression in a way that does not involve the direct inhibition of PRC2 activity by prior methylation of H3K36. This surprising conclusion parallels the findings of Hödl and Basler 28 who replaced all zygotic H3K4 with arginine or alanine and saw no ectopic Polycomb repression of HOX and other developmental genes. From this, they concluded that H3K4 methylation is not critical for Trithorax function at developmental genes. Taken together, our results and the results of Hödl and Basler argue that the model where the methylation of H3K4 and/or H3K36 directly inhibits the catalytic activity of PRC2 is a poor fit to explain how the Trithorax group proteins safeguard the expression of the Polycomb‐regulated developmental genes. Not investigated here, the inhibition of Polycomb complexes by methylated H3K4 and H3K36 may still help to antagonize pervasive hit‐and‐run di‐methylation of H3K27 throughout the genome 57, 58.

If Ash1 does not act via H3K36 methylation, how does it antagonize Polycomb repression of developmental genes? Since the SET domain is required for this aspect of Ash1 function, methyltransferase activity is likely to be involved. It is possible that Ash1 methylates histones at positions other than H3K36 although these are probably not H3K4, H3K9 and H4K20 16, 17, 19. More likely, the relevant substrate of Ash1 activity is a non‐histone protein. Conceivably, it is Trithorax or one of the Polycomb group proteins. Exciting times lie ahead as we start to explore these possibilities.

Materials and Methods

Fly strains

To generate the ash1 22 (w/+; ash1 22 ,P{w +mW.hs =FRT(w hs )2A}/TM3, Ser, e,Act‐GFP[+mW]) fly strain, the w;ash1 22 ,P{w +mW.hs =FRT(w hs )2A}/TM6C,Sb 1 ,Tb 1 (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, #24161) flies were re‐balanced over the TM3, Ser, e, Act‐GFP[+mW] balancer. To generate the w 1118 ; Df(3L)Exel9011/TM3,Ser,e,Act‐GFP[+mW] strain, the w 1118 ; Df(3L)Exel9011/TM6B,Tb 1 flies (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, 7945) were re‐balanced over the TM3,Ser,e,Act‐GFP[+mW] balancer. The ash1 21 (y − ,w 1 ; ash1 21/TM3,Ser) 59 strain was re‐balanced over the TM3,Ser,e,Act‐GFP[+mW] balancer. Oregon R flies were used as wild‐type in all experiments unless stated otherwise. To generate histone H3 mutant strains, the fly strains w,ΔHis3.3B (w + ), hsp‐Flp; Df(2L)His3.3A/SM6B,Cy 51, yw; Elav‐Gal4,ΔHisC/CyO;VK33{H3K36Rx12}/TM6B,Tb and w; UAS‐2xYFP,ΔHisC/CyO,Ftz,lacZ; +/+ (gift from Dr. Gregory Matera, 47) were used. Derivation of flies lacking zygotic His3.3 and His3.2 genes is described in Fig EV5, Appendix Figs S6 and S7. Generation of the ash1 22 ,NSDds46/TM3,Ser,GFP together with ash1 9011 ,NSDds46/TM3,Ser,GFP and ash1 21 ,NSDds46/TM3,Ser,GFP fly strains is described in Appendix Figs S11 and S12. Generation of the Elav‐Gal4,ΔHisC/CyO; ash1 22 ,VK33{H3K36Rx12}/TM6B,Tb and UAS‐2xYFP,ΔHisC/CyO; ash1 9011/TM6B,Tb fly strains is described in Appendix Fig S3. The fly strain y,w,rox1[ex6],rox2[ 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 ]/FM7i,ActGFP; nos[4L],sco[rv9R] b[ 1 ]/CyO,ActGFP; +/+ was a gift from Dr. Maria Kim.

Plasmid construction and generation of Ash1 transgenes

The Ubi‐One‐STrEP::Ash1FL, Ubi‐One‐STrEP::Ash1ΔPHD and Ubi‐One‐STrEP::Ash1ΔSET plasmids were generated using Gateway LR reaction (Invitrogen) between the entry vector containing 5′ One‐STrEP‐tag fused with one of the three variants of Ash1 Open Reading Frame (ORF) and a destination vector which contained the mini‐white marker gene, the attB site and the Ubi‐p63E promoter (pWattB‐Ubi‐DEST) upstream of the recombination sites. To generate pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1FL entry vector, Ash1C (404 bp) and Ash1N (391 bp), DNA fragments were amplified from the Pmt‐V5‐HIS‐ASH1 plasmid (gift from Dr. Vincenzo Pirrotta) using the ASH1CN_Cfwd, ASH1CN_Crev, ASH1CN_Nfwd and ASH1CN_Nrev primers. The nucleotide sequences of all PCR primers used to generate the transgenic constructs are listed in Appendix Table S1. pENTR1A no ccDB (w48‐1) (Addgene plasmid #17398) was digested with KpnI and XhoI. The Ash1N and Ash1C fragments were cloned in the linearized vector using InFusion HD (Clontech) to obtain the pENTR1A‐Ash1NC plasmid. To introduce the One‐STrEP‐tag N‐terminally into pENTR1A‐Ash1NC, the plasmid was linearized with KpnI. The One‐STrEP_fwd and One‐STrEP_rev oligos were annealed in a thermocycler using the following program: 95°C 30 s, 72°C 2 min, 37°C 2 min, 25°C 2 min. The linear pENTR1A‐Ash1NC plasmid and the annealed One‐STrEP oligos were used in an InFusion reaction to obtain the pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1NC plasmid. To clone the full‐length Ash1 CDS, the Pmt‐V5‐HIS‐ASH1 plasmid was digested by BglII and the middle fragment of Ash1 CDS (5.9 kb) was extracted from the gel and ligated into pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1NC, linearized with BglII, to obtain pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1. pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1 was sequenced using the primers ASH1_seq2, ASH1_seq3, ASH1_seq4, ASH1_seq5, ASH1_seq6, ASH1_seq7, ASH1_seq8, ASH1_seq10, ASH1_seq11, ash1‐22.2, ash1‐22.R, ASH1CN_Cfwd and ASH1_mE_Fwd to confirm the integrity of the Ash1 ORF and the One‐STrEP‐tag.

To construct pWattB‐DEST destination vector, the pWattB plasmid 60 was linearized with BamHI and the ends of the resulted fragment blunted using T4 DNA Polymerase (Fermentas). The destination cassette (DEST) was retrieved from pLentiX1PuroDEST (694‐6) (Addgene plasmid #17297) by the EcoRV digestion and extraction of the 1.7 kb band from the agarose gel. Linear pWattB and the destination cassette were ligated to obtain pWattB‐DEST.

The Ubi‐p63E promoter was amplified as described by 60 using the Ubi‐1.1 and Ubi‐1.2 primers. The pWattB‐DEST plasmid was linearized with SpeI (right before the destination cassette), and the Ubi‐p63E promoter was cloned in the linear vector using InFusion to generate pWattB‐Ubi‐DEST.

To generate the plasmids for expression of truncated Ash1 variants, the deletions were introduced to the pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1 entry vector and the modified entry cassette was shuffled into pWattB‐Ubi‐DEST using Invitrogen Gateway™ LR Clonase™ II. To construct pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1ΔSET, the two fragments (upstream deltaSET_AB and downstream deltaSET_CD) flanking the SET domain were amplified from pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1 using the primers deltaSET_A, deltaSET_B, deltaSET_C and deltaSET_D. pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1 was digested with BstZ17I and SphI restriction enzymes. The linearized vector (8.7 kb) was extracted from the agarose gel and used in the InFusion reaction together with the fragments deltaSET_AB and deltaSET_CD to obtain pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1ΔSET. The ASH1_seq7 and ASH1_seq8 primers were used to sequence pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1ΔSET.

To generate pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1ΔPHD, the two fragments (upstream deltaPHD_AB and downstream deltaPHD_CD) flanking the PHD domain were amplified from pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1 using the primers deltaPHD_A, deltaPHD_B, deltaPHD_C and deltaPHD_D. pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1 was digested with KpnI and SphI restriction enzymes. The linearized vector (8.9 kb) was extracted from the agarose gel and used in the InFusion reaction together with the fragments deltaPHD_AB and deltaPHD_CD to obtain pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1ΔPHD. The primers ASH1_seq8, ASH1_seq9 and ASH1_seq12 were used to sequence pENTR1A‐One‐STrEP‐Ash1ΔPHD.

The Ubi‐One‐STrEP::Ash1FL, Ubi‐One‐STrEP::Ash1ΔPHD and Ubi‐One‐STrEP::Ash1ΔSET constructs produced by corresponding Gateway LR reactions were injected into y 1 M[vas‐int.Dm]ZH‐2A w − ; M[3xP3‐RFP.attP’]ZH‐51C embryos by BestGene Inc.

Generation of the NSD null mutation

Most of the Drosophila NSD Open Reading Frame (ORF) was replaced with the DsRed ORF and placed under control of the 3xP3 promoter, using CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated Homology‐Directed Repair. To this effect, target‐specific gRNAs (1gRNA_NSD_sens, 1gRNA_NSD_asen, 2gRNA_NSD_sens and 2gRNA_NSD_asen) were synthesized as 5′‐phosphorylated oligonucleotides, annealed and ligated into the BbsI site of the pU6‐BbsI‐chiRNA vector 43, Addgene plasmid #45946. DNA of the pU6‐1gRNA_NSD‐chiRNA and pU6‐2gRNA_NSD‐chiRNA plasmids was purified and sequenced before injection. To insert DsRed by Homology‐Directed Repair (HDR), the donor plasmid pHD‐DsRed‐attP‐HDRNSD was used. To generate pHD‐DsRed‐attP‐HDRNSD, the pHD‐DsRed‐attP vector was used to clone homology arms flanking the CRISPR/Cas‐9 cleavage sites. The HA‐1 region was amplified (Phusion polymerase, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a forward primer HA‐1‐SpeI containing the SpeI site and a reverse primer HA‐1‐PstI containing the PstI site. The HA‐2 region was amplified with a forward primer HA‐2‐NotI containing the NotI site and a reverse primer HA‐2‐EcoRI containing the EcoRI site. The amplified fragments were inserted into the SpeI/PstI sites and the NotI/EcoRI sites of the pHD‐DsRed‐attP vector (Addgene plasmid #51019), respectively, to generate the donor plasmid pHD‐DsRed‐attP‐HDRNSD 43. pDsRed‐attP was a gift from Melissa Harrison, Kate O'Connor‐Giles and Jill Wildonger. The donor plasmid pHD‐DsRed‐attP‐HDRNSD, together with the guide‐RNA‐Plasmids, pU6‐1gRNA_NSD‐chiRNA, and pU6‐2gRNA_NSD‐chiRNA, were co‐injected into embryos of the fly strain y 2 ,cho 2 ,v 1 ; Sp/CyO,P{nos‐Cas9,y+,v+}2A [NIG‐FLY, CAS‐0001] 61, which expresses Cas9 in the germline. Injected flies were balanced and tested for incorporation of DsRed into the NSD locus. Resulting NSD loss‐of‐function mutants were verified by sequencing and RT–PCR using the primers NSD‐Rt‐1f and NSD‐Rt‐1r. The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers are shown in Appendix Table S1.

Imaginal disc fixation and immunostaining

Haltere imaginal discs from the third instar larvae were dissected in cold 1× PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4) and fixed for 30 min at room temperature with 4% formaldehyde diluted in 1× PBS. The discs were washed three times for 15 min in 1× PBS, 0.3% Triton X‐100 (PBST) and then incubated for 30 min in the blocking solution (5% normal goat serum in PBST) and overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies (anti‐H3K18Ac and anti‐Ubx, Appendix Table S2) diluted in the blocking solution. The discs were further washed three times for 15 min in PBST, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies (Appendix Table S2) diluted in PBST, washed three times for 15 min in PBST and mounted on glass slides in Vectashield mounting media (Vector Laboratories). The mounted discs were imaged with Leica TCS SPE confocal microscope.

Embryo fixation and immunostaining

Fly crosses (Fig EV5) were set up in cages and embryos collected after 24 h. Embryos homozygous for the ΔHisC deletion (YFP+) and the control (YFP−) embryos were selected under the fluorescent stereomicroscope prior to fixation. Embryos were dechorionated for 5 min in 3% bleach. The dechorionated embryos were transferred to a scintillation vial containing 5 ml heptane. 5 ml of the 4% formaldehyde solution diluted in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4) was added to the vial, and it was shaken for 20 min at 350 rpm on the Unimax 2010 shaker (Heidolph). The lower phase (formaldehyde) was removed, and 5 ml of cold methanol was added to the vial. The vial was shaken vigorously for 30 s. The upper phase (heptane) and most of the methanol were removed. Embryos were transferred to a 1.5 ml tube and washed three times for 5 min, in methanol.

Before staining, the embryos were rehydrated in 50% methanol. Then, they were incubated three times for 5 min in 1× PBS, 0.1% Tween‐20 (PBSTW) followed by three times for 15‐min incubation in PBSTW. Next, the embryos were incubated at room temperature for 1 h in the blocking solution (5% normal goat serum in PBST) and then overnight at 4°C in primary antibody diluted in the blocking solution. The embryos were washed four times 15 min in PBSTW, incubated with a secondary antibody diluted in PBSTW and washed again four times 15 min in PBSTW. Then, the embryos were dehydrated by 5‐min incubations in 1 ml of the 30, 50, 70, 95, 100% ethanol solutions. Ethanol was removed, 500 μl of methyl salicylate added, and the embryos incubated overnight at 4°C. After this, the embryos were mounted on a glass slide, covered by 18 × 18 coverslip and imaged with Leica TCS SPE confocal microscope.

Western blot

For analysis of the bulk H3K36 methylation, total extracts prepared from hand‐dissected brains, imaginal discs and salivary glands of the third instar larvae were separated on a 15% SDS–PAGE and blotted to PVDF membrane for 60 min at 200 mA. For analysis of Ash1 protein levels, nuclear extracts from whole 3rd instar larvae were separated on a 6% SDS–PAGE and blotted to PVDF membrane for 3 h at 200 mA. The same extracts were separated on a 15% SDS–PAGE and stained with Coomassie to be used as loading control. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 1× PBS with 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween‐20. For the list of antibodies, see Appendix Table S2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and qPCR analysis were done essentially as described 62 except that crosslinked material was sonicated in 4 ml of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH8.0 with Branson sonicator for 45 min (45 cycles of 20 s ON–40 s OFF, amplitude 40%). Isolated ChIP DNA was re‐suspended in 400 μl of DNase free water, and 4 μl was used for each PCR product. The antibodies used are listed in Appendix Table S2, and ChIP amplicons are listed in Appendix Table S3. The nucleotide sequences of corresponding PCR primers are listed in Appendix Table S1.

Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR

Drosophila embryos were staged and collected is described by 63. For each replicate, 10 embryos were homogenized in TRIzol (SIGMA) and RNA was extracted with chloroform and precipitated with isopropanol using glycogen (Invitrogen) as a carrier. cDNA was synthesized using Random Hexamer primers and RevertAid Minus RT enzyme (Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative PCR was performed with Bio‐Rad Real‐Time System CFX Connect using qPCRBIO SyGreen Mix No‐Rox (Pcrbio) and primer pairs Abd‐B_F_ex and Abd‐B_R_ex; RpL32‐ex1.1 and RpL32‐ex1.2. The PCR conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 20 s at 55°C and 30 s at 72°C. The melting curve was recorded at the end of the cycling program. Six dilutions of wild‐type genomic DNA were used as calibration curve to calculate the starting number of template molecules.

Fly cuticle preparation

Flies were boiled in 10% KOH for 10 min and then incubated in distilled water for 30 min. Fly cuticles were dehydrated in 70% ethanol and 99% ethanol for 10 min each. Ethanol was replaced with glycerol and incubated for 30 min. Cuticle were dissected under the stereomicroscope and mounted on glass slide in glycerol.

Single fly genomic DNA preparation

Single flies were placed in 200‐μl PCR tubes containing 50 μl of the homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl, 200 μg/ml proteinase K). Flies were crushed with a 200‐μl pipette tip, and the resulting fly lysates were incubated for 30 min at 37°C followed by 2 min at 95°C. 3 μl of the lysate was used for each PCR product.

Embryo genomic DNA extraction

One embryo was placed in a 1.5‐ml tube containing 50 μl of sonication buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl) and sonicated for three cycles (30 s ON, 30 s OFF) in Bioruptor® Pico (Diagenode). Proteinase K (0.2 μg/μl) was added to the embryo lysate and incubated 30 min at 37°C followed by 2 min at 95°C. 3 μl of the lysate was used for each PCR product.

Author contributions

ED and YBS conceived the project. ED performed all genetic and immunostaining experiments. ED and MS analysed homeotic phenotypes. TGK performed ChIP experiments and characterized the expression of Ash1 transgenes. AG measured bulk methylated histones by Western blot and characterized Abd‐B expression by qPCR. MW generated the NSD null allele under the supervision of GR. ED and YBS wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jan Larsson for critical comments on the manuscript, Dr. Vincenzo Pirrotta for the gift of the Pmt‐V5‐HIS‐ASH1 plasmid and anti‐Ash1 antibodies, Dr. Harald Saumweber for the gift of anti‐BEAF‐32 antibody and Drs. Mitzi Kuroda, Gregory Matera, Leonie Ringrose, Konrad Basler, Maria Kim, Melissa Harrison, Kate O'Connor‐Giles and Jill Wildonger for generous gifts of fly strains and plasmids. This work was supported in part by grants from Swedish Research Council to YBS and grants from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and Kempestiftelserna to EpiCoN (YBS co‐PI). Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) were used in this study. The Ubx FP3.38 and Abd‐B 1A2E9, monoclonal antibodies developed by R. White and S. Celniker, respectively, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the NICHD of the NIH and maintained at the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242.

EMBO Reports (2019) 20: e46762

References

- 1. Grossniklaus U, Paro R (2014) Transcriptional silencing by polycomb‐group proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6: a019331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schuettengruber B, Bourbon HM, Di Croce L, Cavalli G (2017) Genome regulation by Polycomb and Trithorax: 70 years and counting. Cell 171: 34–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V (2007) Polycomb silencing mechanisms and the management of genomic programmes. Nat Rev Genet 8: 9–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewis EB (1978) A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila . Nature 276: 565–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maeda RK, Karch F (2006) The ABC of the BX‐C: the bithorax complex explained. Development 133: 1413–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ingham PW (1983) Differential expression of bithorax complex genes in the absence of the extra sex combs and Trithorax genes. Nature 306: 591–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tripoulas N, LaJeunesse D, Gildea J, Shearn A (1996) The Drosophila ash1 gene product, which is localized at specific sites on polytene chromosomes, contains a SET domain and a PHD finger. Genetics 143: 913–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tripoulas NA, Hersperger E, La Jeunesse D, Shearn A (1994) Molecular genetic analysis of the Drosophila melanogaster gene absent, small or homeotic discs 1 (ash1). Genetics 137: 1027–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klymenko T, Muller J (2004) The histone methyltransferases Trithorax and Ash1 prevent transcriptional silencing by Polycomb group proteins. EMBO Rep 5: 373–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poux S, Horard B, Sigrist CJ, Pirrotta V (2002) The Drosophila Trithorax protein is a coactivator required to prevent re‐establishment of polycomb silencing. Development 129: 2483–2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V (2013) A new world of Polycombs: unexpected partnerships and emerging functions. Nat Rev Genet 14: 853–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simon JA, Kingston RE (2013) Occupying chromatin: Polycomb mechanisms for getting to genomic targets, stopping transcriptional traffic, and staying put. Mol Cell 49: 808–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pengelly AR, Copur O, Jackle H, Herzig A, Muller J (2013) A histone mutant reproduces the phenotype caused by loss of histone‐modifying factor Polycomb. Science 339: 698–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schmitges FW, Prusty AB, Faty M, Stutzer A, Lingaraju GM, Aiwazian J, Sack R, Hess D, Li L, Zhou S et al (2011) Histone methylation by PRC2 is inhibited by active chromatin marks. Mol Cell 42: 330–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voigt P, LeRoy G, Drury WJ III, Zee BM, Son J, Beck DB, Young NL, Garcia BA, Reinberg D (2012) Asymmetrically modified nucleosomes. Cell 151: 181–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yuan W, Xu M, Huang C, Liu N, Chen S, Zhu B (2011) H3K36 methylation antagonizes PRC2‐mediated H3K27 methylation. J Biol Chem 286: 7983–7989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. An S, Yeo KJ, Jeon YH, Song JJ (2011) Crystal structure of the human histone methyltransferase ASH1L catalytic domain and its implications for the regulatory mechanism. J Biol Chem 286: 8369–8374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith ST, Petruk S, Sedkov Y, Cho E, Tillib S, Canaani E, Mazo A (2004) Modulation of heat shock gene expression by the TAC1 chromatin‐modifying complex. Nat Cell Biol 6: 162–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka Y, Katagiri Z, Kawahashi K, Kioussis D, Kitajima S (2007) Trithorax‐group protein ASH1 methylates histone H3 lysine 36. Gene 397: 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tie F, Banerjee R, Saiakhova AR, Howard B, Monteith KE, Scacheri PC, Cosgrove MS, Harte PJ (2014) Trithorax monomethylates histone H3K4 and interacts directly with CBP to promote H3K27 acetylation and antagonize Polycomb silencing. Development 141: 1129–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ardehali MB, Mei A, Zobeck KL, Caron M, Lis JT, Kusch T (2011) Drosophila Set1 is the major histone H3 lysine 4 trimethyltransferase with role in transcription. EMBO J 30: 2817–2828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hallson G, Hollebakken RE, Li T, Syrzycka M, Kim I, Cotsworth S, Fitzpatrick KA, Sinclair DA, Honda BM (2012) dSet1 is the main H3K4 di‐ and tri‐methyltransferase throughout Drosophila development. Genetics 190: 91–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herz HM, Mohan M, Garruss AS, Liang K, Takahashi YH, Mickey K, Voets O, Verrijzer CP, Shilatifard A (2012) Enhancer‐associated H3K4 monomethylation by Trithorax‐related, the Drosophila homolog of mammalian Mll3/Mll4. Genes Dev 26: 2604–2620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bell O, Wirbelauer C, Hild M, Scharf AN, Schwaiger M, MacAlpine DM, Zilbermann F, van Leeuwen F, Bell SP, Imhof A et al (2007) Localized H3K36 methylation states define histone H4K16 acetylation during transcriptional elongation in Drosophila . EMBO J 26: 4974–4984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Larschan E, Alekseyenko AA, Gortchakov AA, Peng S, Li B, Yang P, Workman JL, Park PJ, Kuroda MI (2007) MSL complex is attracted to genes marked by H3K36 trimethylation using a sequence‐independent mechanism. Mol Cell 28: 121–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feller C, Forne I, Imhof A, Becker PB (2015) Global and specific responses of the histone acetylome to systematic perturbation. Mol Cell 57: 559–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho JW, Jung YL, Liu T, Alver BH, Lee S, Ikegami K, Sohn KA, Minoda A, Tolstorukov MY, Appert A et al (2014) Comparative analysis of metazoan chromatin organization. Nature 512: 449–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hödl M, Basler K (2012) Transcription in the absence of histone H3.2 and H3K4 methylation. Curr Biol 22: 2253–2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bowman SK, Deaton AM, Domingues H, Wang PI, Sadreyev RI, Kingston RE, Bender W (2014) H3K27 modifications define segmental regulatory domains in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Elife 3: e02833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schwartz YB, Kahn TG, Nix DA, Li XY, Bourgon R, Biggin M, Pirrotta V (2006) Genome‐wide analysis of Polycomb targets in Drosophila melanogaster . Nat Genet 38: 700–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwartz YB, Kahn TG, Stenberg P, Ohno K, Bourgon R, Pirrotta V (2010) Alternative epigenetic chromatin states of polycomb target genes. PLoS Genet 6: e1000805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaufman TC, Seeger MA, Olsen G (1990) Molecular and genetic organization of the antennapedia gene complex of Drosophila melanogaster . Adv Genet 27: 309–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duncan IM (1982) Polycomblike: a gene that appears to be required for the normal expression of the bithorax and antennapedia gene complexes of Drosophila melanogaster . Genetics 102: 49–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dura JM, Brock HW, Santamaria P (1985) Polyhomeotic: a gene of Drosophila melanogaster required for correct expression of segmental identity. Mol Gen Genet 198: 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jurgens G (1985) A group of genes controlling the spatial expression of the bithorax complex in Drosophila . Nature 316: 153–155 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shearn A (1989) The ash‐1, ash‐2 and Trithorax genes of Drosophila melanogaster are functionally related. Genetics 121: 517–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schuettengruber B, Ganapathi M, Leblanc B, Portoso M, Jaschek R, Tolhuis B, van Lohuizen M, Tanay A, Cavalli G (2009) Functional anatomy of polycomb and Trithorax chromatin landscapes in Drosophila embryos. PLoS Biol 7: e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kharchenko PV, Alekseyenko AA, Schwartz YB, Minoda A, Riddle NC, Ernst J, Sabo PJ, Larschan E, Gorchakov AA, Gu T et al (2011) Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster . Nature 471: 480–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Papp B, Muller J (2006) Histone trimethylation and the maintenance of transcriptional ON and OFF states by trxG and PcG proteins. Genes Dev 20: 2041–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmahling S, Meiler A, Lee Y, Mohammed A, Finkl K, Tauscher K, Israel L, Wirth M, Philippou‐Massier J, Blum H et al (2018) Regulation and function of H3K36 di‐methylation by the Trithorax‐group protein complex AMC. Development 145: dev163808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang C, Yang F, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Cai G, Li L, Zheng Y, Chen S, Xi R, Zhu B (2017) Mrg15 stimulates Ash1 H3K36 methyltransferase activity and facilitates Ash1 Trithorax group protein function in Drosophila . Nat Commun 8: 1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parks AL, Cook KR, Belvin M, Dompe NA, Fawcett R, Huppert K, Tan LR, Winter CG, Bogart KP, Deal JE et al (2004) Systematic generation of high‐resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat Genet 36: 288–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gratz SJ, Ukken FP, Rubinstein CD, Thiede G, Donohue LK, Cummings AM, O'Connor‐Giles KM (2014) Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9‐catalysed homology‐directed repair in Drosophila . Genetics 196: 961–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dorighi KM, Tamkun JW (2013) The Trithorax group proteins Kismet and ASH1 promote H3K36 dimethylation to counteract Polycomb group repression in Drosophila . Development 140: 4182–4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Butcher RD, Chodagam S, Basto R, Wakefield JG, Henderson DS, Raff JW, Whitfield WG (2004) The Drosophila centrosome‐associated protein CP190 is essential for viability but not for cell division. J Cell Sci 117: 1191–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gunesdogan U, Jackle H, Herzig A (2010) A genetic system to assess in vivo the functions of histones and histone modifications in higher eukaryotes. EMBO Rep 11: 772–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McKay DJ, Klusza S, Penke TJ, Meers MP, Curry KP, McDaniel SL, Malek PY, Cooper SW, Tatomer DC, Lieb JD et al (2015) Interrogating the function of metazoan histones using engineered gene clusters. Dev Cell 32: 373–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marzluff WF, Wagner EJ, Duronio RJ (2008) Metabolism and regulation of canonical histone mRNAs: life without a poly(A) tail. Nat Rev Genet 9: 843–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ahmad K, Henikoff S (2002) The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication‐independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell 9: 1191–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wirbelauer C, Bell O, Schubeler D (2005) Variant histone H3.3 is deposited at sites of nucleosomal displacement throughout transcribed genes while active histone modifications show a promoter‐proximal bias. Genes Dev 19: 1761–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hödl M, Basler K (2009) Transcription in the absence of histone H3.3. Curr Biol 19: 1221–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sakai A, Schwartz BE, Goldstein S, Ahmad K (2009) Transcriptional and developmental functions of the H3.3 histone variant in Drosophila . Curr Biol 19: 1816–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Horard B, Loppin B (2015) Histone storage and deposition in the early Drosophila embryo. Chromosoma 124: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gunesdogan U, Jackle H, Herzig A (2014) Histone supply regulates S phase timing and cell cycle progression. Elife 3: e02443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hartenstein V, Campos‐Ortega JA (1985) Fate‐mapping in wild‐type Drosophila melanogaster I. The spatio–temporal pattern of embryonic cell divisions. Wilehm Roux Arch Dev Biol 194: 181–195 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Reveron‐Gomez N, Gonzalez‐Aguilera C, Stewart‐Morgan KR, Petryk N, Flury V, Graziano S, Johansen JV, Jakobsen JS, Alabert C, Groth A (2018) Accurate recycling of parental histones reproduces the histone modification landscape during DNA replication. Mol Cell 72: 239–249.e235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ferrari KJ, Scelfo A, Jammula S, Cuomo A, Barozzi I, Stutzer A, Fischle W, Bonaldi T, Pasini D (2013) Polycomb‐dependent H3K27me1 and H3K27me2 regulate active transcription and enhancer fidelity. Mol Cell 53: 49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee HG, Kahn TG, Simcox A, Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V (2015) Genome‐wide activities of Polycomb complexes control pervasive transcription. Genome Res 25: 1170–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Steffen PA, Fonseca JP, Ganger C, Dworschak E, Kockmann T, Beisel C, Ringrose L (2013) Quantitative in vivo analysis of chromatin binding of Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins reveals retention of ASH1 on mitotic chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 5235–5250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Savitsky M, Kim M, Kravchuk O, Schwartz YB (2016) Distinct roles of chromatin insulator proteins in control of the Drosophila bithorax complex. Genetics 202: 601–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kondo S, Ueda R (2013) Highly improved gene targeting by germline‐specific Cas9 expression in Drosophila . Genetics 195: 715–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kahn TG, Dorafshan E, Schultheis D, Zare A, Stenberg P, Reim I, Pirrotta V, Schwartz YB (2016) Interdependence of PRC1 and PRC2 for recruitment to polycomb response elements. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 10132–10149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee HK, Wright AP, Zinn K (2009) Live dissection of Drosophila embryos: streamlined methods for screening mutant collections by antibody staining. J Vis Exp 34: e1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Martinez‐Arias A, Lawrence PA (1985) Parasegments and compartments in the Drosophila embryo. Nature 313: 639–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3